Alcohol (drug)

| |||

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɛθənɒl/ | ||

| Other names | Absolute alcohol; Alcohol (USP); Cologne spirit; Drinking alcohol; Ethanol (JAN); Ethylic alcohol; EtOH; Ethyl alcohol; Ethyl hydrate; Ethyl hydroxide; Ethylol; Grain alcohol; Hydroxyethane; Methylcarbinol | ||

| Pregnancy category |

| ||

| Dependence liability | Moderate[1] | ||

| Addiction liability | Moderate (10–15%)[2] | ||

| Routes of administration | Common: By mouth Uncommon: Suppository, inhalation, ophthalmic, insufflation, injection[3] | ||

| Drug class | Depressant; Anxiolytic; Analgesic; Euphoriant; Sedative; Emetic; Diuretic; General anesthetic | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status |

| ||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | 80%+[4][5] | ||

| Protein binding | Weakly or not at all[4][5] | ||

| Metabolism | Liver (90%):[6][8] • Alcohol dehydrogenase • MEOS (CYP2E1) | ||

| Metabolites | Acetaldehyde; Acetic acid; Acetyl-CoA; Carbon dioxide; Water; Ethyl glucuronide; Ethyl sulfate | ||

| Onset of action | Peak concentrations:[6][4] • Range: 30–90 minutes • Mean: 45–60 minutes • Fasting: 30 minutes | ||

| Elimination half-life | Constant-rate elimination at typical concentrations:[7][8][6] • Range: 10–34 mg/dL/hour • Mean (men): 15 mg/dL/hour • Mean (women): 18 mg/dL/hr At very high concentrations (t1/2): 4.0–4.5 hours[5][4] | ||

| Duration of action | 6–16 hours (amount of time that levels are detectable)[9] | ||

| Excretion | • Major: metabolism (into carbon dioxide and water)[4] • Minor: urine, breath, sweat (5–10%)[6][4] | ||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| PDB ligand | |||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

| Formula | C2H6O | ||

| Molar mass | 46.069 g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| Density | 0.7893 g/cm3 (at 20 °C)[10] | ||

| Melting point | −114.14 ± 0.03 °C (−173.45 ± 0.05 °F) [10] | ||

| Boiling point | 78.24 ± 0.09 °C (172.83 ± 0.16 °F) [10] | ||

| Solubility in water | Miscible mg/mL (20 °C) | ||

| |||

| |||

Alcohol (from Arabic al-kuḥl 'the kohl'),[11] sometimes referred to by the chemical name ethanol, is the active ingredient in alcoholic drinks such as beer, wine, and distilled spirits (hard liquor).[12] Alcohol is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant, decreasing electrical activity of neurons in the brain,[13] which causes the characteristic effects of alcohol intoxication ("drunkenness").[14] Among other effects, alcohol produces euphoria, decreased anxiety, increased sociability, sedation, and impairment of cognitive, memory, motor, and sensory function.

Alcohol has a variety of adverse effects. Short-term adverse effects include generalized impairment of neurocognitive function, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and hangover-like symptoms. Alcohol is addictive to humans, and can result in alcohol use disorder, dependence and withdrawal. The long-term effects of alcohol are considered to be a major global public health issue and include liver disease, hepatitis,[15] cardiovascular disease (e.g., cardiomyopathy), polyneuropathy, alcoholic hallucinosis, long-term impact on the brain (e.g., brain damage, dementia, and Marchiafava–Bignami disease),[16][17] and cancers.[18] The adverse effects of alcohol on health are most significant when it is used in excessive quantities or with heavy frequency. However, some of them, such as increased risk of certain cancers, may occur even with light or moderate alcohol consumption.[19][20] In high amounts, alcohol may cause loss of consciousness or, in severe cases, death.

Alcohol has been produced and consumed by humans for its psychoactive effects since c. 7000–6600 BC.[21] Alcohol is the second most consumed psychoactive drug globally, behind caffeine.[22][23] Drinking alcohol is generally socially acceptable and is legal in most countries, unlike with many other recreational substances. However, there are often restrictions on alcohol sale and use, for instance a minimum age for drinking and laws against public drinking and drinking and driving.[24] Alcohol has considerable societal and cultural significance and has important social roles in much of the world. Drinking establishments, such as bars and nightclubs, revolve primarily around the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, and parties, festivals, and social gatherings commonly involve alcohol consumption. Alcohol is related to various societal problems, including drunk driving, accidental injuries, sexual assaults, domestic abuse, and violent crime.[25] Alcohol remains illegal for sale and consumption in a number of countries, mainly in the Middle East. While some religions, including Islam, prohibit alcohol consumption, other religions, such as Christianity and Shinto, utilize alcohol in sacrament and libation.[26][27][28]

Uses

[edit]Recreational

[edit]Ethanol is commonly consumed as a recreational substance by mouth in the form of alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, and spirits. It is commonly used in social settings due to its capacity to enhance sociability. Alcohol consumption while socializing increases occurrences of Duchenne smiling, talking, and social bonding, even when participants are unaware of their alcohol consumption or lack thereof.[29] In a study of the UK, regular drinking was correlated with happiness, feeling that life was worthwhile, and satisfaction with life. According to a causal path analysis, alcohol consumption was not the cause, but rather satisfaction with life resulted in greater happiness and an inclination to visit pubs and develop a regular drinking venue. City centre bars were distinguished by their focus on maximizing alcohol sales. Community pubs had less variation in visible group sizes and longer, more focused conversations than those in city centre bars. Drinking regularly at a community pub led to higher trust in others and better networking with the local community, compared to non-drinkers and city centre bar drinkers.[30] Research on the societal benefits of alcohol is rare.[30]

Food energy

[edit]The USDA uses a figure of 6.93 kilocalories (29.0 kJ) per gram of alcohol (5.47 kcal or 22.9 kJ per ml) for calculating food energy.[31] For distilled spirits, a standard serving in the United States is 44 ml (1.5 US fl oz), which at 40% ethanol (80 proof), would be 14 grams and 98 calories. Alcoholic drinks are considered empty calorie foods because other than food energy they contribute no essential nutrients. However, alcohol is a significant source of food energy for individuals with alcoholism and those who engage in binge drinking. For example, individuals with drunkorexia engage in the combination of self-imposed malnutrition and binge drinking.[32][33] In alcoholics who get most of their daily calories from alcohol, a deficiency of thiamine can produce Korsakoff's syndrome, which is associated with serious brain damage.[34]

Medical

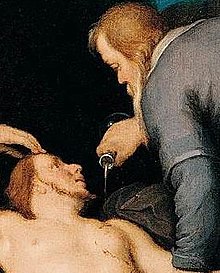

[edit]When fomepizole is not available, ethanol can be used to treat or prevent methanol and/or ethylene glycol toxicity.[35][36] The rate-limiting steps for the elimination of ethanol are in common with these substances, so it competes with other alcohols for the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme. Methanol itself is not highly toxic, but its metabolites formaldehyde and formic acid are; therefore, to reduce the rate of production and concentration of these harmful metabolites, ethanol can be ingested or injected.[37] This avoid toxic aldehyde and carboxylic acid derivatives, and reduces the more serious toxic effects of the glycols when crystallized in the kidneys.[38] Ethylene glycol poisoning can be treated in the same way.

Warfare

[edit]Alcohol has a long association of military use, and has been called "liquid courage" for its role in preparing troops for battle, anaesthetize injured soldiers, and celebrate military victories. It has also served as a coping mechanism for combat stress reactions and a means of decompression from combat to everyday life.[39]

Self-management

[edit]

Accumulating scientific evidence points to alcohol's use in self-management or self-medication. Alcohol can, when applied at a low to medium dose and frequency, have beneficial effects on various behaviors and cognitive issues, including psychiatric symptoms, social phobia, stress, and pain.[40] People who drink for both recreational enjoyment and therapeutic reasons may be more likely to develop alcohol use disorder and experience negative consequences related to their drinking.[41]

Contraindications

[edit]Pregnancy

[edit]

Ethanol is classified as a teratogen[42][43][medical citation needed]—a substance known to cause birth defects; according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), alcohol consumption by women who are not using birth control increases the risk of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs). This group of conditions encompasses fetal alcohol syndrome, partial fetal alcohol syndrome, alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder, static encephalopathy, and alcohol-related birth defects.[44] The CDC currently recommends complete abstinence from alcoholic beverages for women of child-bearing age who are pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or are sexually active and not using birth control.[45]

Peptic ulcer disease

[edit]In patients who have a peptic ulcer disease (PUD), the mucosal layer is broken down by ethanol. PUD is commonly associated with the bacteria Helicobacter pylori, which secretes a toxin that weakens the mucosal wall, allowing acid and protein enzymes to penetrate the weakened barrier. Because alcohol stimulates the stomach to secrete acid, a person with PUD should avoid drinking alcohol on an empty stomach. Drinking alcohol causes more acid release, which further damages the already-weakened stomach wall.[46] Complications of this disease could include a burning pain in the abdomen, bloating and in severe cases, the presence of dark black stools indicate internal bleeding.[47] A person who drinks alcohol regularly is strongly advised to reduce their intake to prevent PUD aggravation.[47]

Allergic-like reactions

[edit]

Ethanol-containing beverages can cause alcohol flush reactions, exacerbations of rhinitis and, more seriously and commonly, bronchoconstriction in patients with a history of asthma, and in some cases, urticarial skin eruptions, and systemic dermatitis. Such reactions can occur within 1–60 minutes of ethanol ingestion, and may be caused by:[50]

- genetic abnormalities in the metabolism of ethanol, which can cause the ethanol metabolite, acetaldehyde, to accumulate in tissues and trigger the release of histamine, or

- true allergy reactions to allergens occurring naturally in, or contaminating, alcoholic beverages (particularly wine and beer), and

- other unknown causes.

Diabetes

[edit]Alcohol consumption can cause hypoglycemia in diabetics on certain medications, such as insulin or sulfonylurea, by blocking gluconeogenesis.[51] Alcohol increases insulin response to glucose promoting fat storage and hindering carbohydrate and fat oxidation.[52][53] This excess processing in the liver acetyl CoA can lead to fatty liver disease and eventually alcoholic liver disease. This progression can lead to further complications, alcohol-related liver disease may cause exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, the inability to properly digest food due to a lack or reduction of digestive enzymes made by the pancreas.[54]

Adverse effects

[edit]

Alcohol has a variety of short-term and long-term adverse effects. Alcohol has both short-term, and long-term effects on the memory, and sleep. It also has reinforcement-related adverse effects, including alcoholism, dependence, and withdrawal. Alcohol use is directly related to considerable morbidity and mortality, for instance due to intoxication and alcohol-related health problems.[55] The World Health Organization advises that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption.[56] Many of the toxic and unpleasant actions of alcohol in the body are mediated by its carcinogenic byproduct acetaldehyde.[57]

Short-term effects

[edit]

The amount of ethanol in the body is typically quantified by blood alcohol content (BAC); weight of ethanol per unit volume of blood. Small doses of ethanol, in general, are stimulant-like[58] and produce euphoria and relaxation; people experiencing these symptoms tend to become talkative and less inhibited, and may exhibit poor judgement. At higher dosages (BAC > 1 gram/liter), ethanol acts as a central nervous system (CNS) depressant,[58] producing at progressively higher dosages, impaired sensory and motor function, slowed cognition, stupefaction, unconsciousness, and possible death.

Hangover

[edit]

A hangover is the experience of various unpleasant physiological and psychological effects usually following the consumption of alcohol, such as wine, beer, and liquor. Hangovers can last for several hours or for more than 24 hours. Typical symptoms of a hangover may include headache, drowsiness, concentration problems, dry mouth, dizziness, fatigue, gastrointestinal distress (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), absence of hunger, light sensitivity, depression, sweating, hyper-excitability, irritability, and anxiety (often referred to as "hangxiety").[59][60]

Long-term effects

[edit]The long-term effects of alcohol have been extensively researched. The health effects of long-term alcohol consumption vary depending on the amount consumed. Even light drinking poses health risks,[61] but atypically small amounts of alcohol may have health benefits.[62] Alcoholism causes severe health consequences which outweigh any potential benefits.[63]

Long-term alcohol consumption is capable of damaging nearly every organ and system in the body.[64] Risks include malnutrition, cirrhosis, chronic pancreatitis, erectile dysfunction, hypertension, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, gastritis, stomach ulcers, alcoholic liver disease,[65] certain types of dementia, and several types of cancer, including oropharyngeal cancer, esophageal cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, and female breast cancers.[66] In addition, damage to the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system (e.g., painful peripheral neuropathy) can occur from chronic heavy alcohol consumption.[67][68] There is also an increased risk for accidental injuries, for example, those sustained in traffic accidents and falls. Excessive alcohol consumption can have a negative impact on aging.[69]

Conversely, light intake of alcohol may have some beneficial effects. The association of alcohol intake with reduced cardiovascular risk has been noted since 1904[70] and remains even after adjusting for known confounders. Light alcohol intake is also associated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes,[71] gastritis, and cholelithiasis.[72] However, these are only observational studies and high-quality evidence for the beneficial effects of alcohol is nonexistent.[73]

Social harms

[edit]

Alcohol causes a plethora of detrimental effects in society.[25] Addiction experts in psychiatry, chemistry, pharmacology, forensic science, epidemiology, and the police and legal services engaged in delphic analysis regarding 20 popular recreational substances. Alcohol was ranked 6th in dependence, 11th in physical harm, and 2nd in social harm.[75] Alcohol use is stereotypically associated with crime,[76] more so than other drugs like marijuana.[25] Many emergency room visits involve alcohol use.[25] As many as 15% of employees show problematic alcohol-related behaviors in the workplace, such as drinking before going to work or even drinking on the job.[25] Drunk dialing refers to an intoxicated person making phone calls that they would not likely make if sober. Alcohol availability and consumption rates and alcohol rates are positively associated with nuisance, loitering, panhandling, and disorderly conduct in open spaces.[76]

Binge drinking

[edit]Binge drinking, or heavy episodic drinking, is drinking alcoholic beverages with an intention of becoming intoxicated by heavy consumption of alcohol over a short period of time. Specific definitions vary considerably.[77] Binge drinking is associated with risks such as suicide, sexual assault, cardiovascular issues, and brain damage, more acutely than alcohol use in general.

Alcohol use disorder

[edit]

Alcoholism or its medical diagnosis alcohol use disorder refers to alcohol addiction, alcohol dependence, dipsomania, and/or alcohol abuse. It is a major problem and many health problems as well as death can result from excessive alcohol use.[25][55] Alcohol dependence is linked to a lifespan that is reduced by about 12 years relative to the average person.[25] In 2004, it was estimated that 4% of deaths worldwide were attributable to alcohol use.[55] Deaths from alcohol are split about evenly between acute causes (e.g., overdose, accidents) and chronic conditions.[55] The leading chronic alcohol-related condition associated with death is alcoholic liver disease.[55] Alcohol dependence is also associated with cognitive impairment and organic brain damage.[25] Some researchers have found that even one alcoholic drink a day increases an individual's risk of health problems by 0.4%.[78]

Two or more consecutive alcohol-free days a week have been recommended to improve health and break dependence.[79][80]

Withdrawal syndrome

[edit]

Discontinuation of alcohol after extended heavy use and associated tolerance development (resulting in dependence) can result in withdrawal. Alcohol is one of the more dangerous drugs to withdraw from.[82] Alcohol withdrawal can cause confusion, paranoia, anxiety, insomnia, agitation, tremors, fever, nausea, vomiting, autonomic dysfunction, seizures, and hallucinations. In severe cases, death can result.

Delirium tremens is a condition of people with a long history of heavy drinking that requires undertaking an alcohol detoxification regimen.

Overdose

[edit]

Symptoms of ethanol overdose may include nausea, vomiting, CNS depression, coma, acute respiratory failure, or death. Levels of even less than 0.1% can cause intoxication, with unconsciousness often occurring at 0.3–0.4%.[83] Death from ethanol consumption is possible when blood alcohol levels reach 0.4%. A blood level of 0.5% or more is commonly fatal. The oral median lethal dose (LD50) of ethanol in rats is 5,628 mg/kg. Directly translated to human beings, this would mean that if a person who weighs 70 kg (150 lb) drank a 500 mL (17 US fl oz) glass of pure ethanol, they would theoretically have a 50% risk of dying. The highest blood alcohol level ever recorded, in which the subject survived, is 1.41%.[84]

Interactions

[edit]Alcohol induced dose dumping (AIDD)

[edit]Alcohol-induced dose dumping (AIDD) is an unintended rapid release of large amounts of a given drug, when administered through a modified-release dosage while co-ingesting ethanol.[85] This is considered a pharmaceutical disadvantage due to the high risk of causing drug-induced toxicity by increasing the absorption and serum concentration above the therapeutic window of the drug. The best way to prevent this interaction is by avoiding the co-ingestion of both substances or using specific controlled-release formulations that are resistant to AIDD. Particular drugs of concern are antipsychotics and certain antidepressants.[83]

Hypnotics and sedatives

[edit]

Alcohol can intensify the sedation caused by hypnotics and sedatives such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, sedative antihistamines, opioids, nonbenzodiazepines/Z-drugs (such as zolpidem and zopiclone).[83]

Disulfiram-like drugs

[edit]Disulfiram

[edit]Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, which in turn results in buildup of acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite of ethanol with unpleasant effects. The medication or drug is commonly used to treat alcohol use disorder, and results in immediate hangover-like symptoms upon consumption of alcohol, this effect is widely known as disulfiram effect.

Metronidazole

[edit]Metronidazole is an antibacterial agent that kills bacteria by damaging cellular DNA and hence cellular function.[86] Metronidazole is usually given to people who have diarrhea caused by Clostridioides difficile bacteria. Patients who are taking metronidazole are sometimes advised to avoid alcohol, even after 1 hour following the last dose. Although older data suggested a possible disulfiram-like effect of metronidazole, newer data has challenged this and suggests it does not actually have this effect.

NSAIDs

[edit]The concomitant use of NSAIDs with alcohol and/or tobacco products significantly increases the already elevated risk of peptic ulcers during NSAID therapy.[87][better source needed]

The risk of stomach bleeding is still increased when aspirin is taken with alcohol or warfarin.[88][89]

Methylphenidate

[edit]Ethanol enhances the bioavailability of methylphenidate (elevated plasma dexmethylphenidate).[90] Ethylphenidate formation appears to be more common when large quantities of methylphenidate and alcohol are consumed at the same time, such as in non-medical use or overdose scenarios.[91] However, only a small percent of the consumed methylphenidate is converted to ethylphenidate.[92]

Nicotine

[edit]While nicotinis mimic the name of classic cocktails like the appletini (their name deriving from "martini"), combining nicotine with alcohol is a bad idea. Tobacco and nicotine actually heighten cravings for alcohol, making this a risky mix.[93]

Caffeine

[edit]Controlled animal and human studies showed that caffeine (energy drinks) in combination with alcohol increased the craving for more alcohol more strongly than alcohol alone.[94] These findings correspond to epidemiological data that people who consume energy drinks generally showed an increased tendency to take alcohol and other substances.[95][96]

Cocaine

[edit]

Ethanol interacts with cocaine in vivo to produce cocaethylene, another psychoactive substance which may be substantially more cardiotoxic than either cocaine or alcohol by themselves.[97][98]

Cannabis

[edit]In combination with cannabis, ethanol increases plasma tetrahydrocannabinol levels, which suggests that ethanol may increase the absorption of tetrahydrocannabinol.[99]

Warfarin

[edit]Excessive use of alcohol is known to affect the metabolism of warfarin and can elevate the INR, and thus increase the risk of bleeding.[100] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) product insert on warfarin states that alcohol should be avoided.[101] The Cleveland Clinic suggests that when taking warfarin one should not drink more than "one beer, 6 oz of wine, or one shot of alcohol per day".[102]

Isoniazid

[edit]Use of isoniazid should be carefully monitored in daily alcohol drinkers since they may be more likely to develop isoniazid-associated hepatitis.[103][104]

Pharmacology

[edit]

Alcohol works in the brain primarily by increasing the effects of γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA),[105] the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain; by facilitating GABA's actions in the GABAA receptor, alcohol suppresses the activity of the central nervous system.[105]

After oral ingestion, ethanol is absorbed via the stomach and intestines into the bloodstream. Ethanol is highly water-soluble and diffuses passively throughout the entire body, including the brain. Soon after ingestion, it begins to be metabolized, 90% or more by the liver. One standard drink is sufficient to almost completely saturate the liver's capacity to metabolize alcohol. The main metabolite is acetaldehyde, a toxic carcinogen. Acetaldehyde is then further metabolized into ionic acetate by the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). Acetate is not carcinogenic and has low toxicity,[106] but has been implicated in causing hangovers.[107][108] Acetate is further broken down into carbon dioxide and water and eventually eliminated from the body through urine and breath. 5 to 10% of ethanol is excreted unchanged in the breath, urine, and sweat.

Alcohol also directly affects a number of other neurotransmitter systems including those of glutamate, glycine, acetylcholine, and serotonin.[109][110] The pleasurable effects of alcohol ingestion are the result of increased levels of dopamine and endogenous opioids in the reward pathways of the brain.[111][112]

Chemistry

[edit]Ethanol is also known chemically as alcohol, ethyl alcohol, or drinking alcohol. It is a simple alcohol with a molecular formula of C2H6O and a molecular weight of 46.0684 g/mol. The molecular formula of ethanol may also be written as CH3−CH2−OH or as C2H5−OH. The latter can also be thought of as an ethyl group linked to a hydroxyl (alcohol) group and can be abbreviated as EtOH. Ethanol is a volatile, flammable, colorless liquid with a slight characteristic odor. Aside from its use as a psychoactive and recreational substance, ethanol is also commonly used as an antiseptic and disinfectant, a chemical and medicinal solvent, and a fuel.

Analogues

[edit]

Ethanol is only one of several types of chemical alcohols, and has a variety of analogues. Most other alcohols are considered poisonous.[12] In general, higher alcohols are less toxic.[113] Alcoholic beverages are sometimes laced with toxic alcohols.

The toxicity of isopropyl alcohol is about twice that of ethanol;[113] a mild, brief exposure to isopropyl alcohol is unlikely to cause any serious harm, although ingesting signficant quantities can lead to vomiting, abdominal pain, and internal bleeding. Methanol is the most toxic alcohol[113] and can cause blindness or death even in small quantities, as little as 10–15 milliliters (2–3 teaspoons).[citation needed] Many methanol poisoning incidents have occurred through history. n-Butanol is reported to produce similar effects to those of ethanol and relatively low toxicity (one-sixth of that of ethanol in one rat study).[114][115] However, its vapors can produce eye irritation and inhalation can cause pulmonary edema.[113] Acetone (propanone) is a ketone rather than an alcohol, and is reported to produce similar toxic effects; it can be extremely damaging to the cornea.[113]

Although ethanol is the most prevalent alcohol in alcoholic beverages, alcoholic beverages contain several types of psychoactive alcohols, that are categorized as primary, secondary, or tertiary. Primary, and secondary alcohols, are oxidized to aldehydes, and ketones, respectively, while tertiary alcohols are generally resistant to oxidation.[116] The Lucas test differentiates between primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols. The tertiary alcohol tert-amyl alcohol (TAA), also known as 2-methylbutan-2-ol (2M2B), has a history of use as a hypnotic and anesthetic, as do other tertiary alcohols such as methylpentynol, ethchlorvynol, and chloralodol. Unlike primary alcohols like ethanol, these tertiary alcohols cannot be oxidized into aldehyde or carboxylic acid metabolites, which are often toxic, and for this reason, these compounds are safer in comparison.[117] Other relatives of ethanol with similar effects include chloral hydrate, paraldehyde, and many volatile and inhalational anesthetics (e.g., chloroform, diethyl ether, and isoflurane).

Manufacturing

[edit]Ethanol is produced naturally as a byproduct of the metabolic processes of yeast and hence is present in any yeast habitat, including even endogenously in humans, but it does not cause raised blood alcohol content as seen in the rare medical condition auto-brewery syndrome (ABS). It is manufactured through hydration of ethylene or by brewing via fermentation of sugars with yeast (most commonly Saccharomyces cerevisiae). The sugars are commonly obtained from sources like steeped cereal grains (e.g., barley), grape juice, and sugarcane products (e.g., molasses, sugarcane juice). Ethanol–water mixture which can be further purified via distillation.

History

[edit]

Alcohol is one of the oldest recreational drugs. Alcoholic beverages have been produced since the Neolithic period, as early as 7000 BC in China.[118] Alcohol was brewed as early as 7,000 to 6,650 BCE in northern China.[21] The earliest evidence of winemaking was dated at 6,000 to 5,800 BCE in Georgia in the South Caucasus.[119] Beer was likely brewed from barley as early as the 13,000 years ago in the Middle East.[120] Pliny the Elder wrote about the golden age of winemaking in Rome, the 2nd century BCE (200–100 BCE), when vineyards were planted.[121]

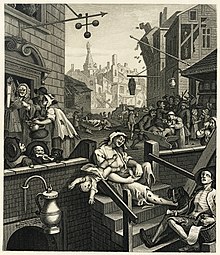

Early modern period

[edit]

The Gin Craze was a period in the first half of the 18th century when the consumption of gin increased rapidly in Great Britain, especially in London. By 1743, England was drinking 2.2 gallons (10 litres) of gin per person per year. The Sale of Spirits Act 1750 (commonly known as the Gin Act 1751) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain (24 Geo. 2. c. 40) which was enacted to reduce the consumption of gin and other distilled spirits, a popular pastime[122] that was regarded as one of the primary causes of crime in London.[123]

Modern period

[edit]

The rum ration (also called the tot) was a daily amount of rum given to sailors on Royal Navy ships. It started 1866 and was abolished in 1970 after concerns that the intake of strong alcohol would lead to unsteady hands when working machinery.

The Andrew Johnson alcoholism debate is the dispute, originally conducted among the general public, and now typically a question for historians, about whether or not Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States (1865–1869), drank to excess.

The prohibition in the United States era was the period from 1920 to 1933 when the United States prohibited the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. The nationwide ban on alcoholic beverages, was repealed by the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 5, 1933.

The Bratt System was a system that was used in Sweden (1919–1955) and similarly in Finland (1944–1970) to control alcohol consumption, by rationing of liquor. Every citizen allowed to consume alcohol was given a booklet called a motbok (viinakortti in Finland), in which a stamp was added each time a purchase was made at Systembolaget (in Sweden) and Alko (in Finland).[124] A similar system also existed in Estonia between July 1, 1920 to December 31, 1925.[125] The stamps were based on the amount of alcohol bought. When a certain amount of alcohol had been bought, the owner of the booklet had to wait until next month to buy more.

The Medicinal Liquor Prescriptions Act of 1933 was a law passed by Congress in response to the abuse of medicinal liquor prescriptions during Prohibition.

Gilbert Paul Jordan (aka The Boozing Barber) was a Canadian serial killer who is believed to have committed the so-called "alcohol murders" between 1965–c. 2004 in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Society and culture

[edit]The consumption of alcohol is deeply embedded in social practices and rituals, often celebrated as a cornerstone of community gatherings and personal milestones. Drinking culture is the set of traditions and social behaviours that surround the consumption of alcoholic beverages as a recreational drug and social lubricant.

Legal status

[edit]Alcohol consumption is fully legal and available in most countries of the world.[126] Home made alcoholic beverages with low alcohol content like wine, and beer is also legal in most countries, but distilling moonshine outside of a registered distillery remains illegal in most of them.

Some majority-Muslim countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Pakistan, Iran and Libya prohibit the production, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages because they are forbidden by Islam.[127][128][129] Also, laws banning alcohol consumption are found in some Indian states as well as some Native American reservations in the U.S.[126]

In addition, there are regulations on alcohol sales and use in many countries throughout the world.[126] For instance, the majority of countries have a minimum legal drinking age to purchase or consume alcoholic beverages, although there are often exceptions such as underage consumption of small amounts of alcohol with parental supervision. Also, some countries have bans on public intoxication.[126] Drinking while driving or intoxicated driving is frequently outlawed and it may be illegal to have an open container of alcohol or liquor bottle in an automobile, bus or aircraft.[126]

Religion

[edit]Religion and alcohol have a complex history. The world's religions have had different relationships with alcohol, reflecting diverse cultural, social, and religious practices across different traditions. While some religions strictly prohibit alcohol consumption, viewing it as sinful or harmful to spiritual and physical well-being, others incorporate it into their rituals and ceremonies. Throughout history, alcohol has held significant roles in religious observances, from the use of sacramental wine in Christian sacraments to the offering and moderate drinking of omiki (sacramental sake) in Shinto purification rituals.

Impact

[edit]A study in 2015 found that alcohol and tobacco use combined resulted in a significant health burden, costing over a quarter of a billion disability-adjusted life years. Illicit drug use caused tens of millions more disability-adjusted life years.[130]

According to The Lancet, 'four industries (tobacco, unhealthy food, fossil fuel, and alcohol) are responsible for at least a third of global deaths per year'.[131] In 2024, the World Health Organization published a report including these figures.[132][133]

Many Native Americans in the United States have been harmed by, or become addicted to, drinking alcohol.[134]

Qualitative analysis reveals that the alcohol industry likely misinforms the public about the dangers of alcohol, similar to the tobacco industry. The alcohol industry influences alcohol policy and health messages, including those for schoolchildren.[135]

Standard drink

[edit]The alcohol consumption recommendations (or safe limits) varies from no intake, to daily, weekly, or daily/weekly guidelines provided by health agencies of governments. The WHO published a statement in The Lancet Public Health in April 2023 that "there is no safe amount that does not affect health."[136]

A standard drink is a measure of alcohol consumption representing a fixed amount of pure ethanol, used in relation to recommendations about alcohol consumption and its relative risks to health. The size of a standard drink varies from 8g to 20g across countries, but 10g alcohol (12.7 millilitres) is used in the World Health Organization (WHO) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)'s questionnaire form example,[137] and has been adopted by more countries than any other amount.[138]

See also

[edit]- Alcohol myopia

- Rum-running

- GABAergics

- GABRD (δ subunit-containing receptors)

- Pigovian taxes, which are to pay for the damage to society caused by these goods.

- Sin taxes are used to increase the price in an effort to lower their use, or failing that, to increase and find new sources of revenue.

- Binge drinking

- Holiday heart syndrome

- Drug-related crime

- List of countries by alcohol consumption per capita

References

[edit]- ^ WHO Expert Committee on Problems Related to Alcohol Consumption: second report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2007. p. 23. ISBN 978-92-4-120944-1. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

...alcohol dependence (is) a substantial risk of regular heavy drinking...

- ^ Vengeliene V, Bilbao A, Molander A, Spanagel R (May 2008). "Neuropharmacology of alcohol addiction". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (2): 299–315. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.30. PMC 2442440. PMID 18311194.

(Compulsive alcohol use) occurs only in a limited proportion of about 10–15% of alcohol users....

- ^ Gilman JM, Ramchandani VA, Crouss T, Hommer DW (January 2012). "Subjective and neural responses to intravenous alcohol in young adults with light and heavy drinking patterns". Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (2): 467–77. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.206. PMC 3242308. PMID 21956438.

- ^ a b c d e f Principles of Addiction: Comprehensive Addictive Behaviors and Disorders. Academic Press. 17 May 2013. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-0-12-398361-9.

- ^ a b c Holford NH (November 1987). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of ethanol". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 13 (5): 273–92. doi:10.2165/00003088-198713050-00001. PMID 3319346. S2CID 19723995.

- ^ a b c d Pohorecky LA, Brick J (1988). "Pharmacology of ethanol". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 36 (2–3): 335–427. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(88)90109-x. PMID 3279433.

- ^ Becker CE (September 1970). "The clinical pharmacology of alcohol". California Medicine. 113 (3): 37–45. PMC 1501558. PMID 5457514.

- ^ a b Levine B (2003). Principles of Forensic Toxicology. Amer. Assoc. for Clinical Chemistry. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-1-890883-87-4.

- ^ Iber FL (26 November 1990). Alcohol and Drug Abuse as Encountered in Office Practice. CRC Press. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-0-8493-0166-7.

- ^ a b c Haynes WM, ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 3.246. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ "The Origin Of The Word 'Alcohol'". Science Friday. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ a b Collins SE, Kirouac M (2013). "Alcohol Consumption". Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. pp. 61–65. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_626. ISBN 978-1-4419-1004-2.

- ^ Costardi JV, Nampo RA, Silva GL, Ribeiro MA, Stella HJ, Stella MB, et al. (August 2015). "A review on alcohol: from the central action mechanism to chemical dependency". Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira. 61 (4): 381–387. doi:10.1590/1806-9282.61.04.381. PMID 26466222.

- ^ "10th Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health: Highlights from Current Research" (PDF). National Institute of Health. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. June 2000. p. 134. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

The brain is a major target for the actions of alcohol, and heavy alcohol consumption has long been associated with brain damage. Studies clearly indicate that alcohol is neurotoxic, with direct effects on nerve cells. Chronic alcohol abusers are at additional risk for brain injury from related causes, such as poor nutrition, liver disease, and head trauma.

- ^ Bruha R, Dvorak K, Petrtyl J (March 2012). "Alcoholic liver disease". World Journal of Hepatology. 4 (3): 81–90. doi:10.4254/wjh.v4.i3.81. PMC 3321494. PMID 22489260.

- ^ Brust JC (April 2010). "Ethanol and cognition: indirect effects, neurotoxicity and neuroprotection: a review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (4): 1540–57. doi:10.3390/ijerph7041540. PMC 2872345. PMID 20617045.

- ^ Venkataraman A, Kalk N, Sewell G, Ritchie CW, Lingford-Hughes A (March 2017). "Alcohol and Alzheimer's Disease-Does Alcohol Dependence Contribute to Beta-Amyloid Deposition, Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's Disease?". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 52 (2): 151–158. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agw092. hdl:10044/1/42603. PMID 27915236.

- ^ de Menezes RF, Bergmann A, Thuler LC (2013). "Alcohol consumption and risk of cancer: a systematic literature review". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 14 (9): 4965–72. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.9.4965. PMID 24175760.

- ^ Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, et al. (February 2013). "Light alcohol drinking and cancer: a meta-analysis". Annals of Oncology. 24 (2): 301–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds337. PMID 22910838.

- ^ Yasinski, Emma, Even If You Don't Drink Daily, Alcohol Can Mess With Your Brain, Discover (magazine), January 12, 2021

- ^ a b McGovern PE, Zhang J, Tang J, Zhang Z, Hall GR, Moreau RA, et al. (December 2004). "Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (51): 17593–8. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10117593M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. PMC 539767. PMID 15590771.

- ^ Song F, Walker MP (8 November 2023). "Sleep, alcohol, and caffeine in financial traders". PLOS ONE. 18 (11): e0291675. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1891675S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0291675. PMC 10631622. PMID 37939019.

Alcohol and caffeine are two of the most widely consumed psychoactive substances in the world.

- ^ Ferré S (June 2013). "Caffeine and Substance Use Disorders". Journal of Caffeine Research. 3 (2): 57–58. doi:10.1089/jcr.2013.0015. PMC 3680974. PMID 24761274.

Caffeine is the most consumed psychoactive drug in the world.

- ^ Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, et al. (2010). Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955114-9. OCLC 656362316.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Butcher JN, Hooley JM, Mineka SM (25 June 2013). Abnormal Psychology. Pearson Education. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-205-97175-6.

- ^ Ruthven M (1997). Islam : a very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-154011-0. OCLC 43476241.

- ^ "Eucharist | Definition, Symbols, Meaning, Significance, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ Bocking B (1997). A popular dictionary of Shintō (Rev. ed.). Richmond, Surrey [U.K.]: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1051-5. OCLC 264474222.

- ^ Sayette MA, Creswell KG, Dimoff JD, Fairbairn CE, Cohn JF, Heckman BW, et al. (August 2012). "Alcohol and group formation: a multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding". Psychological Science. 23 (8): 869–878. doi:10.1177/0956797611435134. PMC 5462438. PMID 22760882.

- ^ a b Dunbar RI, Launay J, Wlodarski R, Robertson C, Pearce E, Carney J, et al. (June 2017). "Functional Benefits of (Modest) Alcohol Consumption". Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology. 3 (2): 118–133. doi:10.1007/s40750-016-0058-4. PMC 7010365. PMID 32104646.

- ^ "Composition of Foods Raw, Processed, Prepared USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 26 Documentation and User Guide" (PDF). USDA. August 2013. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Osborne VA, Sher KJ, Winograd RP (2011). "Disordered eating patterns and alcohol misuse in college students: Evidence for "drunkorexia"?". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 52 (6): e12. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.04.038.

- ^ "'Drunkorexia:' A Recipe for Disaster". ScienceDaily. 17 October 2011.

- ^ Kopelman MD, Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall EJ (2009). "The Korsakoff syndrome: clinical aspects, psychology and treatment". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 44 (2): 148–154. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn118. PMID 19151162.

- ^ British National Formulary: BNF 69 (69th ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 42, 838. ISBN 978-0-85711-156-2.

- ^ Mégarbane B (24 August 2010). "Treatment of patients with ethylene glycol or methanol poisoning: focus on fomepizole". Open Access Emergency Medicine. 2: 67–75. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S5346. PMC 4806829. PMID 27147840.

- ^ McCoy HG, Cipolle RJ, Ehlers SM, Sawchuk RJ, Zaske DE (November 1979). "Severe methanol poisoning. Application of a pharmacokinetic model for ethanol therapy and hemodialysis". The American Journal of Medicine. 67 (5): 804–7. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)90766-6. PMID 507092.

- ^ Barceloux DG, Bond GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA (2002). "American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 40 (4): 415–46. doi:10.1081/CLT-120006745. PMID 12216995. S2CID 26495651.

- ^ Jones E, Fear NT (April 2011). "Alcohol use and misuse within the military: a review". International Review of Psychiatry. 23 (2): 166–172. doi:10.3109/09540261.2010.550868. PMID 21521086.

- ^ Müller CP, Schumann G, Rehm J, Kornhuber J, Lenz B (July 2023). "Self-management with alcohol over lifespan: psychological mechanisms, neurobiological underpinnings, and risk assessment". Molecular Psychiatry. 28 (7): 2683–2696. doi:10.1038/s41380-023-02074-3. PMC 10615763. PMID 37117460.

- ^ Ferguson E, Fiore A, Yurasek AM, Cook RL, Boissoneault J (February 2023). "Association of therapeutic and recreational reasons for alcohol use with alcohol demand". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 31 (1): 106–115. doi:10.1037/pha0000554. PMC 9399303. PMID 35201830.

- ^ Popova S, Dozet D, Shield K, Rehm J, Burd L (September 2021). "Alcohol's Impact on the Fetus". Nutrients. 13 (10): 3452. doi:10.3390/nu13103452. PMC 8541151. PMID 34684453.

- ^ Chung DD, Pinson MR, Bhenderu LS, Lai MS, Patel RA, Miranda RC (August 2021). "Toxic and Teratogenic Effects of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure on Fetal Development, Adolescence, and Adulthood". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (16): 8785. doi:10.3390/ijms22168785. PMC 8395909. PMID 34445488.

- ^ "Facts about FASDs". 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ "More than 3 million US women at risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancy". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 February 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

'drinking any alcohol at any stage of pregnancy can cause a range of disabilities for their child,' said Coleen Boyle, Ph.D., director of CDC's National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

- ^ Peters GL, Rosselli JL, Kerr JL. "Overview of Peptic Ulcer Disease: Etiology and Pathophysiology". Medscape.com. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ a b Dumain T. Pathak N (ed.). "Peptic Ulcer Disease (Stomach Ulcers) Cause, Symptoms, Treatments". Webmd.com. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A (March 2009). "The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption". PLOS Medicine. 6 (3): e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050. PMC 2659709. PMID 19320537.

- ^ McMurran M (3 October 2012). Alcohol-Related Violence: Prevention and Treatment. John Wiley & Sons. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-118-41106-3.

- ^ Adams KE, Rans TS (December 2013). "Adverse reactions to alcohol and alcoholic beverages". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 111 (6): 439–45. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.09.016. PMID 24267355.

- ^ "Alcohol & Diabetes – ADA". American Diabetes Association. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Metz R, Berger S, Mako M (August 1969). "Potentiation of the plasma insulin response to glucose by prior administration of alcohol. An apparent islet-priming effect" (PDF). Diabetes. 18 (8): 517–522. doi:10.2337/diab.18.8.517. PMID 4897290. S2CID 32072796. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Shelmet JJ, Reichard GA, Skutches CL, Hoeldtke RD, Owen OE, Boden G (April 1988). "Ethanol causes acute inhibition of carbohydrate, fat, and protein oxidation and insulin resistance". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 81 (4): 1137–1145. doi:10.1172/JCI113428. PMC 329642. PMID 3280601.

- ^ Leeds JS, Oppong K, Sanders DS (May 2011). "The role of fecal elastase-1 in detecting exocrine pancreatic disease". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 8 (7): 405–415. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.91. PMID 21629239.

- ^ a b c d e Friedman HS (26 August 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 699–. ISBN 978-0-19-534281-9.

- ^ "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". www.who.int. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Burcham PC (19 November 2013). An Introduction to Toxicology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-1-4471-5553-9.

- ^ a b Hendler RA, Ramchandani VA, Gilman J, Hommer DW (2013). Stimulant and sedative effects of alcohol. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 13. pp. 489–509. doi:10.1007/7854_2011_135. ISBN 978-3-642-28719-0. PMID 21560041.

- ^ Stephens R, Ling J, Heffernan TM, Heather N, Jones K (23 January 2008). "A review of the literature on the cognitive effects of alcohol hangover". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 43 (2): 163–170. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agm160. PMID 18238851.

- ^ "Hangxiety: why alcohol can leave you feeling anxious". Queensland Health. Queensland Health. The State of Queensland. 26 July 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". www.who.int.

- ^ Bryazka D, Reitsma MB, Griswold MG, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. (GBD 2020 Alcohol Collaboration) (July 2022). "Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020". The Lancet. 400 (10347): 185–235. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00847-9. PMC 9289789. PMID 35843246.

- ^ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2000). "Health risks and benefits of alcohol consumption" (PDF). Alcohol Res Health. 24 (1): 5–11. doi:10.4135/9781412963855.n839. ISBN 9781412941860. PMC 6713002. PMID 11199274. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2006.

- ^ Caan W, de Belleroche J, eds. (11 April 2002). Drink, Drugs and Dependence: From Science to Clinical Practice (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-415-27891-1.

- ^ Cargiulo T (March 2007). "Understanding the health impact of alcohol dependence". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 64 (5 Suppl 3): S5–11. doi:10.2146/ajhp060647. PMID 17322182.

- ^ Cheryl Platzman Weinstock (8 November 2017). "Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Breast and Other Cancers, Doctors Say". Scientific American. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

In fact, alcohol consumption is known to increase the risk of several cancers, including head and neck, esophageal, liver, colorectal and female breast cancers.

- ^ Müller D, Koch RD, von Specht H, Völker W, Münch EM (1985). "Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse". Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) (in German). 37 (3): 129–132. PMID 2988001.

- ^ Testino G (2008). "Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view". Hepatogastroenterology. 55 (82–83): 371–377. PMID 18613369.

- ^ Stevenson JS (2005). "Alcohol use, misuse, abuse, and dependence in later adulthood". Annu Rev Nurs Res. 23: 245–280. doi:10.1891/0739-6686.23.1.245. PMID 16350768. S2CID 24586529.

- ^ Cabot, R.C. (1904). "The relation of alcohol to arteriosclerosis". Journal of the American Medical Association. 43 (12): 774–775. doi:10.1001/jama.1904.92500120002a.

- ^ Schrieks IC, Heil AL, Hendriks HF, Mukamal KJ, Beulens JW (2015). "The effect of alcohol consumption on insulin sensitivity and glycemic status: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies". Diabetes Care. 38 (4): 723–732. doi:10.2337/dc14-1556. PMID 25805864. S2CID 32005728.

- ^ Taylor B, Rehm J, Gmel G (2005). "Moderate alcohol consumption and the gastrointestinal tract". Dig Dis. 23 (3–4): 170–176. doi:10.1159/000090163. PMID 16508280. S2CID 30141003.

- ^ Fekjær HO (December 2013). "Alcohol-a universal preventive agent? A critical analysis". Addiction. 108 (12): 2051–2057. doi:10.1111/add.12104. PMID 23297738.

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ a b Sunga HE (2016). "Alcohol and Crime". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. American Cancer Society. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa039.pub2. ISBN 9781405165518.

- ^ Renaud SC (2001). "Diet and stroke". The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 5 (3): 167–172. PMID 11458287.

- ^ Bakalar N (27 August 2018). "How Much Alcohol Is Safe to Drink? None, Say These Researchers". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Tomlinson A (26 June 2018). "Tips and Tricks on How to Cut Down on the Booze". The West Australian. Seven West Media (WA). Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Alcohol". British Liver Trust. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Ashworth M, Gerada C (August 1997). "ABC of mental health. Addiction and dependence – II: Alcohol". BMJ. 315 (7104): 358–360. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7104.358. PMC 2127236. PMID 9270461.

- ^ Fisher GL, Roget NA, eds. (2009). "Withdrawal: Alcohol". Encyclopedia of substance abuse prevention, treatment, & recovery. Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 1005. ISBN 978-1-4522-6601-5. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Yost DA (2002). "Acute care for alcohol intoxication" (PDF). Postgraduate Medicine Online. 112 (6). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ "Drunkest driver in SA arrested". SowetanLIVE. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ D'Souza S, Mayock S, Salt A (December 2017). "A review of in vivo and in vitro aspects of alcohol-induced dose dumping". AAPS Open. 3 (1). doi:10.1186/s41120-017-0014-9. ISSN 2364-9534.

- ^ Repchinsky C (ed.) (2012). Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialties, Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association.[full citation needed]

- ^ Agrawal N (June 1991). "Risk factors for gastrointestinal ulcers caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)". The Journal of Family Practice. 32 (6): 619–624. PMID 2040888.

- ^ "Aspirin information from Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ "Oral Aspirin information". First DataBank. Archived from the original on 18 September 2000. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ Patrick KS, Straughn AB, Minhinnett RR, Yeatts SD, Herrin AE, DeVane CL, et al. (March 2007). "Influence of ethanol and gender on methylphenidate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 81 (3): 346–353. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100082. PMC 3188424. PMID 17339864.

- ^ Markowitz JS, Logan BK, Diamond F, Patrick KS (August 1999). "Detection of the novel metabolite ethylphenidate after methylphenidate overdose with alcohol coingestion". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (4): 362–366. doi:10.1097/00004714-199908000-00013. PMID 10440465.

- ^ Markowitz JS, DeVane CL, Boulton DW, Nahas Z, Risch SC, Diamond F, et al. (June 2000). "Ethylphenidate formation in human subjects after the administration of a single dose of methylphenidate and ethanol". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 28 (6): 620–624. doi:10.1016/S0090-9556(24)15139-2. PMID 10820132.

- ^ Verplaetse TL, McKee SA (March 2017). "An overview of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in the human laboratory". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 43 (2): 186–196. doi:10.1080/00952990.2016.1189927. PMC 5588903. PMID 27439453.

- ^ Curran CP, Marczinski CA (December 2017). "Taurine, caffeine, and energy drinks: Reviewing the risks to the adolescent brain". Birth Defects Research. 109 (20): 1640–1648. doi:10.1002/bdr2.1177. PMC 5737830. PMID 29251842.

- ^ Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, O'Grady KE, Vincent KB, Griffiths RR, et al. (June 2010). "Increased alcohol consumption, nonmedical prescription drug use, and illicit drug use are associated with energy drink consumption among college students". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 4 (2): 74–80. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181aa8dd4. PMC 2923814. PMID 20729975.

- ^ "Energy drinks and risk to future substance use". www.drugabuse.gov. National Institute on Drug Abuse. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Laizure SC, Mandrell T, Gades NM, Parker RB (January 2003). "Cocaethylene metabolism and interaction with cocaine and ethanol: role of carboxylesterases". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 31 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.1.16. PMID 12485948.

- ^ Pergolizzi J, Breve F, Magnusson P, LeQuang JA, Varrassi G (February 2022). "Cocaethylene: When Cocaine and Alcohol Are Taken Together". Cureus. 14 (2): e22498. doi:10.7759/cureus.22498. PMC 8956485. PMID 35345678.

- ^ Lukas SE, Orozco S (October 2001). "Ethanol increases plasma Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) levels and subjective effects after marihuana smoking in human volunteers". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 64 (2): 143–9. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00118-1. PMID 11543984.

- ^ Weathermon R, Crabb DW (1999). "Alcohol and medication interactions". Alcohol Research & Health. 23 (1): 40–54. PMC 6761694. PMID 10890797.

- ^ "PRODUCT INFORMATION COUMADIN" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Aspen Pharma Pty Ltd. 19 January 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Warfarin Anticoagulant Medication". Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Isoniazid tablet". DailyMed. 18 October 2018. Archived from the original on 13 March 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ Saukkonen JJ, Cohn DL, Jasmer RM, Schenker S, Jereb JA, Nolan CM, et al. (October 2006). "An official ATS statement: hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis therapy". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 174 (8): 935–952. doi:10.1164/rccm.200510-1666ST. PMID 17021358. S2CID 36384722.

- ^ a b Lobo IA, Harris RA (July 2008). "GABA(A) receptors and alcohol". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 90 (1): 90–94. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.006. PMC 2574824. PMID 18423561.

- ^ "Acetate, Ion chromatography standard solution, Safety Data Sheet". Thermo Fisher Scientific. 1 April 2024. p. 4.

- ^ Maxwell CR, Spangenberg RJ, Hoek JB, Silberstein SD, Oshinsky ML (December 2010). "Acetate causes alcohol hangover headache in rats". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15963. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515963M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015963. PMC 3013144. PMID 21209842.

- ^ Holmes B (15 January 2011). "Is coffee the real cure for a hangover?". New Scientist. p. 17.

- ^ Narahashi T, Kuriyama K, Illes P, Wirkner K, Fischer W, Mühlberg K, et al. (May 2001). "Neuroreceptors and ion channels as targets of alcohol". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25 (5 Suppl ISBRA): 182S – 188S. doi:10.1097/00000374-200105051-00030. PMID 11391069.

- ^ Olsen RW, Li GD, Wallner M, Trudell JR, Bertaccini EJ, Lindahl E, et al. (March 2014). "Structural models of ligand-gated ion channels: sites of action for anesthetics and ethanol". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 38 (3): 595–603. doi:10.1111/acer.12283. PMC 3959612. PMID 24164436.

- ^ Charlet K, Beck A, Heinz A (2013). The dopamine system in mediating alcohol effects in humans. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 13. pp. 461–88. doi:10.1007/7854_2011_130. ISBN 978-3-642-28719-0. PMID 21533679.

- ^ Méndez M, Morales-Mulia M (June 2008). "Role of mu and delta opioid receptors in alcohol drinking behaviour". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 1 (2): 239–52. doi:10.2174/1874473710801020239. PMID 19630722.

- ^ a b c d e Philp RB (15 September 2015). Ecosystems and Human Health: Toxicology and Environmental Hazards, Third Edition. CRC Press. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-1-4987-6008-9.

- ^ n-Butanol (PDF), SIDS Initial Assessment Report, Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme, April 2005.

- ^ McCreery MJ, Hunt WA (July 1978). "Physico-chemical correlates of alcohol intoxication". Neuropharmacology. 17 (7): 451–61. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(78)90050-3. PMID 567755. S2CID 19914287.

- ^ Clark J, Farmer S, Kennepohl D, Kabrhel J, Ashenhurst J, Ashenhurst J (26 August 2015). "17.7: Oxidation of Alcohols". Chemistry LibreTexts.

- ^ Carey F (2000). Organic Chemistry (4 ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-290501-8. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Vidrih R, Hribar J (2016). "Mead: The Oldest Alcoholic Beverage". In Kristbergsson K, Oliveira J (eds.). Traditional Foods. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 325–338. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-7648-2_26. ISBN 978-1-4899-7646-8. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ McGovern P, Jalabadze M, Batiuk S, Callahan MP, Smith KE, Hall GR, et al. (November 2017). "Early Neolithic wine of Georgia in the South Caucasus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (48): E10309 – E10318. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11410309M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1714728114. PMC 5715782. PMID 29133421.

- ^ Rosso AM (2012). "Beer and wine in antiquity: beneficial remedy or punishment imposed by the Gods?". Acta medico-historica Adriatica. 10 (2): 237–62. PMID 23560753.

- ^ Brostrom GG, Brostrom JJ (30 December 2008). The Business of Wine: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-313-35401-4.

- ^ "History of Alcohol" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ "Gin Act". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Motbok" [Counter book]. Förvaltningshistorisk ordbok [Administrative history dictionary] (in Swedish). Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Arjakas K (8 November 2008). "Alkoholikeeldudest Eestis" [Alcohol bans in Estonia]. Postimees (in Estonian). Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Boyle P (7 March 2013). Alcohol: Science, Policy and Public Health. OUP Oxford. pp. 363–. ISBN 978-0-19-965578-6.

- ^ "Getting a drink in Saudi Arabia". BBC News. BBC. 8 February 2001. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Can you drink alcohol in Saudi Arabia?". 1 August 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "13 Countries With Booze Bans". Swifty.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, Colledge S, Hickman M, Rehm J, et al. (October 2018). "Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report". Addiction. 113 (10): 1905–1926. doi:10.1111/add.14234. hdl:11343/283940. PMID 29749059.

- ^ "Unravelling the commercial determinants of health". The Lancet (Editorial). 401 (10383): 1131. 23 March 2023. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00590-1. PMID 36966781.

- ^ "Just four industries cause 2.7 million deaths in the European Region every year". World Health Organization. 12 June 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

Four corporate products – tobacco, ultra-processed foods, fossil fuels and alcohol – cause 19 million deaths per year globally, or 34% of all deaths.

- ^ Bawden A, Campbell D (12 June 2024). "Tobacco, alcohol, processed foods and fossil fuels 'kill 2.7m a year in Europe'". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ Szlemko WJ, Wood JW, Thurman PJ (October 2006). "Native Americans and alcohol: past, present, and future". The Journal of General Psychology. 133 (4). Heldref Publications: 435–451. doi:10.3200/GENP.133.4.435-451. PMID 17128961. S2CID 43082343.

- ^ Petticrew M, Maani Hessari N, Knai C, Weiderpass E (March 2018). "How alcohol industry organisations mislead the public about alcohol and cancer" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Review. 37 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1111/dar.12596. PMID 28881410.

- ^ "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". World Health Organization. 4 January 2023.

- ^ "AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Second Edition)" (pdf). WHO. 2001. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Kalinowski A, Humphreys K (July 2016). "Governmental standard drink definitions and low-risk alcohol consumption guidelines in 37 countries". Addiction. 111 (7): 1293–1298. doi:10.1111/add.13341. PMID 27073140.

Further reading

[edit]- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1988). Alcohol Drinking. International Agency for Research on Cancer.

External links

[edit]- "ETOH Database Search". hazelden.org.

- The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism maintains a database of alcohol-related health effects. ETOH Archival Database (1972–2003) Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Science Database.

- "Harmful Interactions". National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

- WHO fact sheet on alcohol

- ChEBI – biology related

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes signal transduction pathway: KEGG – human alcohol addiction

- 5-HT3 agonists

- AMPA receptor antagonists

- Adenosine reuptake inhibitors

- Alcohol-related crimes

- Alcohol

- Alcohol abuse

- Alcohol and health

- Alcohol dehydrogenase inhibitors

- Alcohol law

- Alcohols

- Analgesics

- Anaphrodisia

- Anxiolytics

- Calcium channel blockers

- Chemical hazards

- Depressogens

- Diuretics

- Drinking culture

- Drug culture

- Drugs acting on the nervous system

- Drugs with unknown mechanisms of action

- Emetics

- Ethanol

- Euphoriants

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

- General anesthetics

- Glycine reuptake inhibitors

- Hepatotoxins

- Human metabolites

- Hypnotics

- IARC Group 1 carcinogens

- Kainate receptor antagonists

- NMDA receptor antagonists

- Neurotoxins

- Nicotinic agonists

- Ototoxicity

- Psychoactive drugs

- Sedatives

- Teratogens