Zaleplon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2018) |

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trade names | Sonata, others | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph | ||

| MedlinePlus | a601251 | ||

| License data | |||

| Addiction liability | Moderate | ||

| Routes of administration | By mouth | ||

| Drug class | nonbenzodiazepine | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | 30% (oral)[4] | ||

| Metabolism | Liver aldehyde oxidase (91%), CYP3A4 (9%)[9] | ||

| Metabolites | No active metabolites[5] | ||

| Onset of action | 10 to 30 minutes[6] | ||

| Elimination half-life | 1 hr[4] | ||

| Duration of action | Approximately 4 to 6 hours[6][7][8] | ||

| Excretion | Kidney | ||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.126.674 | ||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

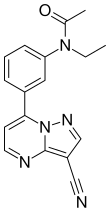

| Formula | C17H15N5O | ||

| Molar mass | 305.341 g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| |||

| |||

| (verify) | |||

Zaleplon, sold under the brand name Sonata among others, is a sedative and hypnotic which is used to treat insomnia. It is a nonbenzodiazepine or Z-drug of the pyrazolopyrimidine class.[10] It was developed by King Pharmaceuticals and approved for medical use in the United States in 1999.[3]

Medical uses

[edit]Zaleplon is slightly effective in treating insomnia,[11] primarily characterized by difficulty falling asleep. Zaleplon significantly reduces the time required to fall asleep by improving sleep latency and may therefore facilitate sleep induction rather than sleep maintenance.[12][13][14] Due to its ultrashort elimination half-life, zaleplon may not be effective in reducing premature awakenings; however, it may be administered to alleviate middle-of-the-night awakenings.[12] However, zaleplon has not been empirically shown to increase total sleep time.[14][12]

Zaleplon does not significantly affect driving performance the morning following bedtime administration or 4 hours after middle-of-the-night administration. [15] It may have advantages over benzodiazepines with fewer adverse effects.[16]

Special populations

[edit]Zaleplon is not recommended for chronic use in the elderly.[17] The elderly are more sensitive to the adverse effects of zaleplon such as cognitive side effects. Zaleplon may increase the risk of injury among the elderly. It should not be used during pregnancy or lactation. Clinicians should devote more attention when prescribing for patients with a history of alcohol or drug abuse, psychotic illness, or depression.[18]

In addition, some contend the efficacy and safety of long-term use of these agents remains to be enumerated, but nothing concrete suggests long-term use poses any direct harm to a person.[19]

Adverse effects

[edit]The adverse effects of zaleplon are similar to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines, although with less next-day sedation,[20] and in two studies zaleplon use was found not to cause an increase in traffic accidents, as compared to other hypnotics currently on the market.[21][22]

Sleeping pills, including zaleplon, have been associated with an increased risk of death.[23]

Some evidence suggests zaleplon is not as chemically reinforcing and exhibits far fewer rebound effects when compared with other nonbenzodiazepines, or Z-drugs.[24]

Interactions

[edit]The CYP3A4 liver enzyme is a minor metabolic pathway for zaleplon, normally metabolizing about 9% of the drug.[9] CYP3A4 inducers such as rifampicin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital can reduce the effectiveness of zaleplon, and therefore the FDA suggests that other hypnotic drugs be considered in patients taking a CYP3A4 inducer.[9]

Additional sedation has been observed when zaleplon is combined with thioridazine, but it is not clear whether this was due to merely an additive effect of taking two sedative drugs at once or a true drug-drug interaction.[25] Diphenhydramine, a weak inhibitor of aldehyde oxidase, has not been found to affect the pharmacokinetics of zaleplon.[25]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Zaleplon is a high-selectivity,[26] high-affinity ligand of positive modulatory benzodiazepine sites on GABAA receptors. Zaleplon binds preferentially at benzodiazepine sites on α1-containing GABAA receptors (previously known as BZ1/Ω1 receptors), which largely mediate the sedative effects of benzodiazepines.[27] However, unlike zolpidem, zaleplon binds with appreciable affinity to benzodiazepine sites on some α2 and α3-containing GABAA receptors, which are implicated in the anxiolytic and muscle relaxant effects of benzodiazepines. Zaleplon demonstrates greater selectivity at these sites than lorazepam or zopiclone.[28][29]

Unlike nonselective benzodiazepine drugs and zopiclone, which distort the sleep pattern, zaleplon appears to induce sleep without disrupting the normal sleep architecture.[30]

A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials which compared benzodiazepines against zaleplon or other Z-drugs such as zolpidem, zopiclone, and eszopiclone has found few clear and consistent differences between zaleplon and the benzodiazepines in terms of sleep onset latency, total sleep duration, number of awakenings, quality of sleep, adverse events, tolerance, rebound insomnia, and daytime alertness.[31]

Zaleplon should be understood as an ultrashort-acting sedative-hypnotic drug for the treatment of insomnia. Zaleplon increases EEG power density in the δ-frequency band and a decrease in the energy of the θ-frequency band.[32][33] In contrast to non-selective benzodiazepine drugs and zopiclone, zaleplon does not increase power in the β-frequency band.[34]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The ultrashort 1hr half-life gives Zaleplon a unique advantage over other hypnotics because of its lack of next-day residual effects on driving and other performance-related skills.[35][36]

Zaleplon is primarily metabolised by aldehyde oxidase into 5-oxozaleplon, and its half-life may be affected by substances which inhibit or induce aldehyde oxidase. According to urine analysis, about 9% of zaleplon is metabolized by CYP3A4 to form desethylzaleplon, which is quickly metabolized by aldehyde oxidase to 5-oxodesethylzaleplon.[9][4] All of these metabolites are inactive.[4] When taken orally, zaleplon reaches maximum concentration in about 45 minutes.[4]

Chemistry

[edit]Zaleplon is classified as a pyrazolopyrimidine.[37] Pure zaleplon in its solid state is a white to off-white powder with very low solubility in water, as well as low solubility in ethanol and propylene glycol.[9] It has a constant octanol-water partition coefficient of log P = 1.23 in the pH range between 1 and 7.[9]

Synthesis

[edit]

The synthesis starts with the condensation of 3-acetylacetanilide[40][41] (1) with N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal (DMFDMA)[42] to give the eneamide (2). The anilide nitrogen is then alkylated by means of sodium hydride and ethyl iodide to give 3. The first step in the condensation with 3-amino-4-cyanopyrazole can be visualized as involving an addition-elimination reaction sequence on the eneamide function to give a transient intermediate such as 5. Cyclization then leads to the formation of the fused pyrimidine ring to afford zaleplon (6).

Society and culture

[edit]Recreational use

[edit]Zaleplon has the potential to be a drug of recreational use, and has been found to have an addictive potential similar to benzodiazepine and benzodiazepine-like hypnotics.[43]

Some individuals use a different delivery method than prescribed, such as insufflation, to induce effects faster.[44]

Anterograde amnesia can occur and can cause one to lose track of the amount of zaleplon already ingested, prompting the ingesting of more than originally planned.[45][46]

Aviation use

[edit]The Federal Aviation Administration allows zaleplon with a 12-hour wait period and no more than twice a week, which makes it the sleep medication with the shortest allowed waiting period after use.[47] The substances with the 2nd shortest period, which is of 24 hours, are zolpidem and ramelteon.[47]

Military use

[edit]The United States Air Force uses zaleplon as one of the hypnotics approved as a "no-go pill" to help aviators and special-duty personnel sleep in support of mission readiness (with a four-hour restriction on subsequent flight operation). "Ground tests" are required prior to authorization being issued to use the medication in an operational situation.[48] The other hypnotics used as "no-go pills" are temazepam and zolpidem, which both have longer mandatory recovery periods.[48]

References

[edit]- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Sonata (zaleplon) Capsules CIV". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Rosen AS, Fournié P, Darwish M, Danjou P, Troy SM (April 1999). "Zaleplon pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 20 (3): 171–175. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199904)20:3<171::aid-bdd169>3.0.co;2-k. PMID 10211871.

- ^ Coke JM, Edwards MD (April 2009). "Minimal and moderate oral sedation in the adult special needs patient". Dental Clinics of North America. 53 (2): 221–30, viii. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2008.12.005. PMID 19269393.

Zaleplon (Sonata) has the shortest half-life of the Z-drugs of 1 hour and reaches peak plasma level in 1 hour. It is rapidly absorbed in under1 hour and has no active metabolites. The recommended adult dose is 5–20 mg.

- ^ a b Bechtel LK, Holstege CP (May 2007). "Criminal poisoning: drug-facilitated sexual assault". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 25 (2): 499–525, abstract x. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.02.008. PMID 17482030.

Zaleplon is available as an immediate-release tablet or capsule. An average oral dose of 10 to 15 mg has a rapid onset of clinical symptoms of approximately 10 to 30 minutes. Although the t1/2 for zaleplon is about 1 hour, the duration of clinical effects may persist for greater than 6 hours. This persistence may be because of the higher affinity of zaleplon for specific α2 and α3 subunits of the GABA receptor, unlike zolpidem or zopiclone [74].

- ^ "SONATA - zaleplon capsule". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

Do not take Sonata unless you are able to get 4 or more hours of sleep before you must be active again. DO NOT use alcohol while taking Sonata or any other sleep medicine. Be sure to tell your physician if you suffer from depression. Sonata works very quickly. You should only take Sonata immediately before going to bed or after you have gone to bed and are having difficulty falling asleep. For Sonata to work best, you should not take Sonata with or immediately after a high-fat/heavy meal. Some people should start with the lowest dose (5 mg) of Sonata; these include the elderly (ie, ages 65 and over) and people with liver disease.

- ^ Khouzam HR, Gill TS, Tan DT (2007). "The Patient with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder". Handbook of Emergency Psychiatry. Elsevier. pp. 453–473. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-04088-4.50026-x. ISBN 978-0-323-04088-4.

The adult dose is 10 mg, and 5 mg for geriatric patients.

- ^ a b c d e f "20859 S009, 011 FDA Approved Labeling Text 12.10.07" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Elie R, Rüther E, Farr I, Emilien G, Salinas E (August 1999). "Sleep latency is shortened during 4 weeks of treatment with zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic. Zaleplon Clinical Study Group". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (8): 536–44. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0806. PMID 10485636.

- ^ Huedo-Medina TB, Kirsch I, Middlemass J, Klonizakis M, Siriwardena AN (December 2012). "Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". BMJ. 345: e8343. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8343. PMC 3544552. PMID 23248080.

- ^ a b c Bhandari P, Sapra A (2020). "Zaleplon". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31855398. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Ebbens MM, Verster JC (20 July 2010). "Clinical evaluation of zaleplon in the treatment of insomnia". Nature and Science of Sleep. 2: 115–126. doi:10.2147/nss.s6853. PMC 3630939. PMID 23616704.

- ^ a b Dooley M, Plosker GL (August 2000). "Zaleplon: a review of its use in the treatment of insomnia". Drugs. 60 (2): 413–445. doi:10.2165/00003495-200060020-00014. PMID 10983740. S2CID 195691571.

- ^ Verster JC, Veldhuijzen DS, Volkerts ER (August 2004). "Residual effects of sleep medication on driving ability". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 8 (4): 309–25. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.02.001. hdl:1874/11902. PMID 15233958. S2CID 22856696.

- ^ Barbera J, Shapiro C (2005). "Benefit-risk assessment of zaleplon in the treatment of insomnia". Drug Safety. 28 (4): 301–18. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528040-00003. PMID 15783240. S2CID 24222535.

- ^ Fick D, Semla T, Beizer J, Brandt N, Dombrowski R, DuBeau CE, et al. (American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel) (April 2012). "American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (4): 616–31. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. PMC 3571677. PMID 22376048.

- ^ Antai-Otong D (August 2006). "The art of prescribing. Risks and benefits of non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists in the treatment of acute primary insomnia in older adults". Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 42 (3): 196–200. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00070.x. PMID 16916422.

- ^ Bain KT (June 2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 4 (2): 168–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- ^ Wagner J, Wagner ML, Hening WA (June 1998). "Beyond benzodiazepines: alternative pharmacologic agents for the treatment of insomnia". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 32 (6): 680–91. doi:10.1345/aph.17111. PMID 9640488. S2CID 34250754.

- ^ Menzin J, Lang KM, Levy P, Levy E (January 2001). "A general model of the effects of sleep medications on the risk and cost of motor vehicle accidents and its application to France". PharmacoEconomics. 19 (1): 69–78. doi:10.2165/00019053-200119010-00005. PMID 11252547. S2CID 45013069.

- ^ Vermeeren A, Riedel WJ, van Boxtel MP, Darwish M, Paty I, Patat A (March 2002). "Differential residual effects of zaleplon and zopiclone on actual driving: a comparison with a low dose of alcohol". Sleep. 25 (2): 224–31. PMID 11905433.

- ^ Kripke DF (February 2016). "Mortality Risk of Hypnotics: Strengths and Limits of Evidence". Drug Safety. 39 (2): 93–107. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0362-0. PMID 26563222. S2CID 7946506.

- ^ Lader MH (January 2001). "Implications of hypnotic flexibility on patterns of clinical use". International Journal of Clinical Practice. Supplement (116): 14–9. PMID 11219327.

- ^ a b Wang JS, DeVane CL (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of the sedative hypnotics" (PDF). Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 37 (1): 10–29. doi:10.1007/BF01990373. PMID 14561946. S2CID 1543185. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ Noguchi H, Kitazumi K, Mori M, Shiba T (January 2002). "Binding and neuropharmacological profile of zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic". European Journal of Pharmacology. 434 (1–2): 21–28. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01502-3. PMID 11755161.

Binding assays show no binding (IsC50 > 10,000 micromolar) with regards to the 5HT1, 5HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT3, D1, D2, alpha-1 adrenoceptor, alpha-2 adrenoceptor, or M1 receptors.

- ^ Patat A, Paty I, Hindmarch I (July 2001). "Pharmacodynamic profile of Zaleplon, a new non-benzodiazepine hypnotic agent". Human Psychopharmacology. 16 (5): 369–392. doi:10.1002/hup.310. PMID 12404558.

- ^ Dämgen K, Lüddens H (1999). "Zaleplon displays a selectivity to recombinant GABAA receptors different from zolipdem, zopiclone and benzodiazepines". Neuroscience Research Communications. 25 (3): 139–148. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6769(199911/12)25:3<139::AID-NRC3>3.0.CO;2-W. ISSN 1520-6769.

- ^ Zeilhofer HU, Witschi R, Hösl K (May 2009). "Subtype-selective GABAA receptor mimetics--novel antihyperalgesic agents?". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 87 (5): 465–469. doi:10.1007/s00109-009-0454-3. PMID 19259638.

- ^ Noguchi H, Kitazumi K, Mori M, Shiba T (January 2002). "Binding and neuropharmacological profile of zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic". European Journal of Pharmacology. 434 (1–2): 21–28. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01502-3. PMID 11755161.

- ^ Dündar Y, Dodd S, Strobl J, Boland A, Dickson R, Walley T (July 2004). "Comparative efficacy of newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Psychopharmacology. 19 (5): 305–22. doi:10.1002/hup.594. PMID 15252823. S2CID 10888200.

- ^ Noguchi H, Kitazumi K, Mori M, Shiba T (March 2004). "Electroencephalographic properties of zaleplon, a non-benzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic, in rats". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 94 (3): 246–51. doi:10.1254/jphs.94.246. PMID 15037809.

- ^ Petroski RE, Pomeroy JE, Das R, Bowman H, Yang W, Chen AP, et al. (April 2006). "Indiplon is a high-affinity positive allosteric modulator with selectivity for alpha1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 317 (1): 369–77. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.096701. PMID 16399882. S2CID 46510829.

- ^ Herman JH, Sheldon SH (January 2005). "Chapter 28 - Pharmacology of Sleep Disorders in Children". In Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH (eds.). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 327–338. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7216-9458-0.50033-7. ISBN 978-0-7216-9458-0.

- ^ Patat A, Paty I, Hindmarch I (July 2001). "Pharmacodynamic profile of Zaleplon, a new non-benzodiazepine hypnotic agent". Human Psychopharmacology. 16 (5): 369–392. doi:10.1002/hup.310. PMID 12404558. S2CID 21096374.

- ^ Rowlett JK, Spealman RD, Lelas S, Cook JM, Yin W (January 2003). "Discriminative stimulus effects of zolpidem in squirrel monkeys: role of GABA(A)/alpha1 receptors". Psychopharmacology. 165 (3): 209–215. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1275-z. PMID 12420154. S2CID 37632215.

- ^ "Zaleplon". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ US 4626538, Dusza JP, Tomcufcik AS, Albright JD, "[7-(3-disubstituted amino)phenyl]pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines", issued 2 December 1986, assigned to American Cyanamid Co and King Pharmaceuticals Research and Development Inc.

- ^ Huang X, Li Y, You Q (May 2002). "Synthesis of Zaleplon". China Pharmacist. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Banasik M, Komura H, Shimoyama M, Ueda K (January 1992). "Specific inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase and mono(ADP-ribosyl)transferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (3): 1569–1575. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)45983-2. PMID 1530940.

- ^ Dehmel F, Weinbrenner S, Julius H, Ciossek T, Maier T, Stengel T, et al. (July 2008). "Trithiocarbonates as a novel class of HDAC inhibitors: SAR studies, isoenzyme selectivity, and pharmacological profiles". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 51 (13): 3985–4001. doi:10.1021/jm800093c. PMID 18558669.

- ^ Salomon RG, Raychaudhuri SR (1984). "Convenient preparation of N,N-dimethylacetamide dimethyl acetal". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 49 (19): 3659–3660. doi:10.1021/jo00193a045.

- ^ "Sonata (zaleplon) Capsules". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, Liappas I (November 2008). "Intranasal zaleplon abuse". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 165 (11): 1489–90. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030452. PMID 18981079. Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ Rush CR, Frey JM, Griffiths RR (July 1999). "Zaleplon and triazolam in humans: acute behavioral effects and abuse potential". Psychopharmacology. 145 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1007/s002130051030. PMID 10445371. S2CID 12061258.

- ^ Ator NA (December 2000). "Zaleplon and triazolam: drug discrimination, plasma levels, and self-administration in baboons". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 61 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00123-X. PMID 11064184.

- ^ a b "Zaleplon". Medication Database. Aviation Medicine Advisory Service (AMAS).

- ^ a b Caldwell JA, Caldwell JL (July 2005). "Fatigue in military aviation: an overview of US military-approved pharmacological countermeasures" (pdf). Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 76 (7 Suppl): C39-51. PMID 16018329.