Yemeni civil war (2014–present)

| Yemeni civil war | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Yemeni crisis, the Arab Winter, the war on terror, and the Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict | ||||||||

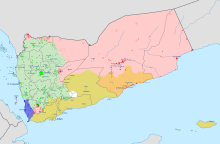

Political and military control in Yemen in February 2024: Republic of Yemen (recognized by United Nations), pro-PLC Yemeni Armed Forces and General People's Congress

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Main belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Saudi-led coalition: |

Casualties:

Casualties:

| ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

|

1,800 security contractors[96] |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

"Thousands" killed (per Al Jazeera; as of May 2018) 11,000+ killed (Arab Coalition claim; as of December 2017)[102] |

Saudi losses

Emirati losses

1 F-16 crashed[122] 1 F-16 shot down[126] American losses | |||||||

|

Overall 377,000+ direct and indirect deaths (150,000+ people killed in violence) (2014–2021) (UN)[129][130] 85,000 Yemeni children dead from starvation (2015–2018) (Save the Children)[131] ~4,000 dead from cholera epidemic; 2.5+ million cases overall (2016–2021)[132] 4 million people cumulatively displaced (2015–2020) (UNHCR)[133][134] 500+ killed in Saudi Arabia by Houthi attacks (2014–2016) (Saudi Arabia figure)[135] 3 civilians killed in the UAE | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Yemen |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Part of a series on the Yemeni crisis |

|---|

|

The Yemeni civil war (Arabic: الحرب الأهلية اليمنية, romanized: al-ḥarb al-ʾahlīyah al-yamanīyah) is an ongoing multilateral civil war that began in late 2014 mainly between the Rashad al-Alimi-led Presidential Leadership Council and the Mahdi al-Mashat-led Supreme Political Council, along with their supporters and allies. Both claim to constitute the official government of Yemen.[136]

The civil war began in September 2014 when Houthi forces took over the capital city Sanaa, which was followed by a rapid Houthi takeover of the government. On 21 March 2015, the Houthi-led Supreme Revolutionary Committee declared a general mobilization to overthrow then-president Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and expand their control by driving into southern provinces.[137] The Houthi offensive, allied with military forces loyal to former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, began fighting the next day in Lahij Governorate. By 25 March, Lahij fell to the Houthis and they reached the outskirts of Aden, the seat of power for Hadi's government.[138] Hadi fled the country the same day.[139][140] Concurrently, a coalition led by Saudi Arabia launched military operations by using air strikes and restored the former Yemeni government.[29] Although there has been no direct intervention by the Iranian government in Yemen, the civil war is widely regarded as part of the Iran-Saudi proxy conflict.[d]

Houthi insurgents currently control the capital Sanaa and all of former North Yemen except for eastern Marib Governorate. After the formation of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) in 2017 and the subsequent capture of Aden by the STC forces in 2018, the pro-republican forces became fractured, with regular clashes between pro-Hadi forces backed by Saudi Arabia and southern separatists backed by the United Arab Emirates.[141] Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State have also carried out attacks against both factions, with AQAP controlling swathes of territory in the hinterlands, and along stretches of the coast.[142]

The UN brokered a two-month nationwide truce on 2 April 2022 between Yemen's warring parties, which allowed fuel imports into Houthi-held areas and some flights to operate from Sanaa International Airport to Jordan and Egypt.[143] On 7 April 2022, the Hadi government was dissolved and the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) took command of the Yemeni Republic, incorporating the Southern Transitional Council into its new government. The UN announced on 2 June 2022 that the nationwide truce had been further extended by two months.[144] According to the UN, over 150,000 people have been killed in Yemen,[145] as well as estimates of more than 227,000 dead as a result of an ongoing famine and lack of healthcare facilities due to the war.[146][130][147] The Wall Street Journal reported in March 2023 that Iran agreed to halt all military support to the Houthis and abide by the UN arms embargo, as part of a Chinese-brokered Iran-Saudi rapprochement deal. The agreement is viewed as part of Saudi Arabian-led efforts to pressure the Houthi militants to end the conflict through negotiated settlement; with Saudi and U.S. officials describing the concomitant Iranian behaviour as a "litmus test" for the endurance of the Chinese-brokered détente.[e] Since then, however, Iran has maintained military and logistical support to the Houthis.[148][149] On 23 December 2023, Hans Grundberg, the UN special envoy for Yemen, announced that the warring parties committed to steps towards a ceasefire.[150]

The Saudi-led coalition's bombing of civilian areas has received condemnation from the international community.[151] According to the Yemen Data Project, the bombing campaign has killed or injured an estimated 19,196 civilians as of March 2022.[152] Houthi drone attacks targeting civilian areas in Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Southern Yemen have also attracted global condemnation;[f] and the UN Security Council has imposed a global arms embargo on the Houthis since 2015.[g] The United States has provided intelligence and logistical support for the Saudi Arabian-led campaign,[27] and despite the Biden administration's pledge to withdraw U.S. support for Saudi Arabia in Yemen, it has announced the sale of weapons to the Saudi Arabian-led coalition.[153][154]

Historical context

[edit]Islam in Yemen predominantly takes the form of Sunni and Shia Islam.[155] Among the Shia, the Ismaili and Zaydi sects historically competed for influence.[156] Following the fall of the Ismaili states ruled by the Hamdan tribe in the 11th century, the Ayyubid expansion led to the majority of the Hamdan tribe converting to Zaydism, a Shia sect.[157]

During the Rasulid period, Shafi'i Sunni Islam gained popularity in Yemen.[158] Over time, the Zaydis in the north and the Rasulid rulers in the south competed for dominance. This rivalry diminished following the decline of Rasulid rule and the increasing involvement of imperial powers in the Middle East, including the Ottoman Empire.[157]

The defeat of the Ottomans in the first World War eventually gave way to the first (incomplete) unification of Yemen. This was possible during the Hamid al-Din dynasty under Imam Yahya and his son's rule. The unification also meant the establishment of a hierarchy within which Zaydis had authoritative power over Sunnis.[157] As a consequence, the difference in status became instituted and normalized. The Hamid al-Din dynasty faced the Zaydis' discontent due to a non-conformity to Zaydi traditions, thus coming to an end with the overthrow of Imam Yahya's grandson, Imam Badr, in 1962. What followed was a civil war in which republicans opposed royalists. Helen Lackner explains that such a division was not ideological; it was based on past feuds. Nonetheless, external powers like Saudi Arabia intervened for ideological motives, as the latter sought to maintain the monarchy system which it adhered to itself. Despite Saudi Arabia's original intentions, in 1970, the republican form was retained.[157]

While these developments took place in the North, liberation movements against British presence broke out, amounting to the creation of a socialist state, hence Soviet Union ally, in the Southern Arabian region. It was named the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY).[157]

The PDRY was involved in the internal disputes of its northern counterpart. It had previously supported the republicans in fighting off Saudi Arabia's influence, but it was the Hamdi regime in the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) that was most notorious for its policies that aimed to reduce Saudi presence in Yemeni politics. His rule was, nonetheless, short-lived. A series of political unrest marked by the assassination of former presidents, led to Colonel Ali Abdullah Saleh's rise to the presidency of the Yemen Arab Republic. Saleh's rule lasted for 33 years. The major event that marked his regime was the unification of Yemen in 1990. His attempt was not entirely successful as a civil war broke out in 1994. However, he was able to come out of it victorious. Subsequently, the Republic of Yemen became constitutionally established.[157]

Saleh tried to maintain his position through constitutional amendments, hoping for his son to take over, but strong opposition and protests pressured him out of office. Meanwhile, the group "Friends of Yemen" was created, initially to stop al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) after evidence pointed at it as the main perpetrator behind multiple attacks on US military bases and equipment. The "Friends of Yemen" group became more involved in Yemen during the Arab Spring, after the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and United Nations recommended that the management of Yemen's "crisis" be put in the hands of global actors.[159]

The Houthis

[edit]After the end of their rule, from the 1960s onwards, Zaydis faced discrimination and Sunnification policies from the consequent Sunni dominated governments. For example, Salafis in Saada claimed al-Shawkani as an intellectual precursor, and future Yemeni regimes would uphold his Sunnization policies as a unifier of the country[160] and to undermine Zaydi Shi'ism.[161]

Ansar Allah (sometimes Anglicised as Ansarullah), known popularly as the Houthis, is a Zaydi group with its origins in the mountainous Sa'dah Governorate on Yemen's northern border with Saudi Arabia. They led a low-level insurgency against the Yemeni government in 2004[162] after their leader, Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, was killed in a government military crackdown[163][164] following his protests against government policies.[165][166]

The intensity of the conflict waxed and waned over the course of the 2000s, with multiple peace agreements being negotiated and later disregarded.[167][168] The Houthi insurgency heated up in 2009, briefly drawing neighboring Saudi Arabia to the side of the Yemeni government, but cooled the following year after a ceasefire was signed.[169][170]

Then during the early stages of the Yemeni Revolution in 2011, Houthi leader Abdul-Malik al-Houthi declared the group's support for demonstrations calling for the resignation of President Ali Abdullah Saleh.[171] Later that year, as Saleh prepared to leave office, the Houthis laid siege to the Salafi-majority village of Dammaj in northern Yemen, a step toward attaining virtual autonomy for Sa'dah.[172]

The Houthis boycotted a single-candidate election in early 2012 meant to give Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi a two-year term of office.[173] They participated in a National Dialogue Conference, but withheld support from a final accord in early 2014 that extended Hadi's mandate in office for another year.[174][175]

Conflict between the Houthis and Sunni tribes in northern Yemen spread to other governorates, including the Sanaa Governorate by mid-2014.[176]

Course of the conflict

[edit]Beginning of the conflict

[edit]After several weeks of street protests against the Hadi administration, which made cuts to fuel subsidies that were unpopular with the group, the Houthis fought the Yemen Army forces under the command of General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar. In a battle that lasted only a few days, Houthi fighters seized control of Sanaa, the Yemeni capital, in September 2014.[177] The Houthis forced Hadi to negotiate an agreement to end the violence, in which the government resigned and the Houthis gained an unprecedented level of influence over state institutions and politics.[178][179]

In January 2015, unhappy with a proposal to split the country into six federal regions,[180] Houthi fighters seized the presidential compound in Sanaa. The power play prompted the resignation of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and his ministers.[175][181] The Houthi political leadership then announced the dissolution of parliament and the formation of a Revolutionary Committee to govern the country on 6 February 2015.[182]

On 21 February, one month after Houthi militants confined Hadi to his residence in Sanaʽa, he slipped out of the capital and traveled to Aden. In a televised address from his hometown, he declared that the Houthi takeover was illegitimate and indicated he remained the constitutional president of Yemen.[183][184][185] His predecessor as president, Ali Abdullah Saleh—who had been widely suspected of aiding the Houthis during their takeover of Sanaʽa the previous year—publicly denounced Hadi and called on him to go into exile.[186]

On 19 March 2015, the troops loyal to Hadi clashed with those who refused to recognize his authority in the Battle of Aden Airport. The forces under General Abdul-Hafez al-Saqqaf were defeated, and al-Saqqaf fled toward Sanaʽa.[187] In apparent retaliation for the routing of al-Saqqaf, warplanes reportedly flown by Houthi pilots bombed Hadi's compound in Aden.[188]

After the 20 March 2015 Sanaa mosque bombings, in a televised speech, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, the leader of the Houthis, said his group's decision to mobilize for war was "imperative" under current circumstances and that Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and its affiliates—among whom he counts Hadi—would be targeted, as opposed to southern Yemen and its citizens.[189] President Hadi declared Aden to be Yemen's temporary capital while Sanaʽa remained under Houthi control.[190][191]

Also, the same day as the mosque bombings, al-Qaeda militants captured the provincial capital of Lahij, Al Houta District after killing about 20 soldiers before being driven out several hours later.[192]

Hadi reiterated in a speech on 21 March 2015 that he was the legitimate president of Yemen and declared, "We will restore security to the country and hoist the flag of Yemen in Sanaʽa, instead of the Iranian flag."[193] He also declared Aden to be Yemen's "economic and temporary capital" due to the Houthi occupation of Sanaʽa, which he pledged would be retaken.[194]

In Sanaa, the Houthi Revolutionary Committee appointed Major General Hussein Khairan as Yemen's new Defence Minister and placed him in overall command of the military offensive.[195][196]

Foreign involvement

[edit]Houthi allies

[edit]In April 2015, United States National Security Council spokeswoman Bernadette Meehan stated that: "It remains our assessment that Iran does not exert command and control over the Houthis in Yemen".[197][198]

The United States has regularly accused the Iranian government of arming and funding the Houthis. In an April 2015 interview with the PBS Newshour, then-U.S. secretary of state John Kerry accused Iran of attempting to destabilize Yemen.[199] While the Houthis and the Iranian government have denied any military affiliation,[200] Iranian supreme leader Ali Khamenei openly announced his "spiritual" support of the movement in a personal meeting with the Houthi spokesperson Mohammed Abdul Salam in Tehran, in the midst of ongoing conflicts in Aden in 2019.[201][202]

Although there has been no direct intervention by the Iranian government, the Yemeni civil war is widely regarded as part of the Iran-Saudi proxy conflict.[h] The United States, Saudi Arabia, UAE and various Western commentators have accused various IRGC networks of assisting Houthis through arms supplies, military training, logistics, strategic co-ordination and media support.[203][204][205] Saudi Arabia views activities by the Quds Forces and Hezbollah in neighboring Yemen as part of Iranian attempts to establish a satellite state in the country and trap them into a stalemate.[206][207] Western commentators have argued that the Iranian policy in Yemen has been hinged on developing bases for ballistic missiles targeting GCC countries, establishing naval dominance in the strategic Bab al-Mandeb Strait by advancing area denial capabilities and weapons trafficking, in addition to the intensification of Iranian cyberwarfare.[203][208] However, this characterization has been disputed by various analysts and academics, who assert that Houthis are independent of Iran. According to professor Stephen Zunes, the majority of Houthi arms supplies primarily originate from the black market, and Houthis obtain most of their weaponry from non-Iranian sources.[209]

On 7 August 2018, IRGC commander Nasser Shabani was quoted by the Fars News Agency, the semi-official news agency of the Iranian government, as saying, "We (IRGC) told Yemenis [Houthi rebels] to strike two Saudi oil tankers, and they did it".[210][211] The Wall Street Journal reported in March 2023 that the Iranian government agreed to halt all military support to Houthis and abide by the UN arms embargo, as part of a Chinese-brokered Iran-Saudi rapprochement deal.[i]

The Eritrean government has also been accused of funneling Iranian material to the Houthis,[212] as well as offering medical care for injured Houthi fighters.[213] However, it has called the allegations "groundless" and said after the outbreak of open hostilities that it views the Yemeni crisis "as an internal matter".[212] According to a secret United Nations document, North Korea had aided the Houthis by selling weapons.[8][214]

Yemeni government supporters

[edit]The Yemeni government meanwhile has enjoyed significant international backing from the United States and Persian Gulf monarchies. U.S. drone strikes were conducted regularly in Yemen during Hadi's presidency in Sanaa, usually targeting Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[215] The United States was also a major supplier of weapons to the Yemeni government, although according to the Pentagon, hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of that material has gone missing since it was delivered.[216] Saudi Arabia provided financial aid to Yemen until late 2014, when it suspended it amid the Houthis' takeover of Sanaʽa and increasing influence over the Yemeni government.[217] According to Amnesty International, the United Kingdom also supplied weaponry used by Saudi-led coalition to strike targets in Yemen.[218] Amnesty International also says that U.S.-based Raytheon Company supplied a laser-guided bomb that killed six civilians on 28 June 2019.[219]

In May 2019, State Secretary Mike Pompeo announced an "emergency" to push through $8.1 billion of arms sales to Gulf allies like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan, citing Iranian activity in the Middle East. Despite widespread congressional opposition, an August 2020 report by the Office of Inspector General detailed that Pompeo complied with the legal prerequisites to do so. The report, however, also noted that the possible threat to the lives of the civilians caught in the crossfire was not assessed properly at the time of the emergency. The State Department was also accused in the report of violating the threshold of the Arms Export Control Act while approving arms sales to Gulf states.[220]

Saudi-led intervention in Yemen

[edit]

In response to rumors that Saudi Arabia could intervene in Yemen, Houthi commander Ali al-Shami boasted on 24 March 2015 that his forces would invade the larger kingdom and not stop at Mecca, but rather Riyadh.[221]

The following evening, answering a request by Yemen's internationally recognized government, Saudi Arabia began a military intervention alongside eight other Arab states and with the logistical support of the United States against the Houthis, bombing positions throughout Sanaʽa. In a joint statement, the nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council (with the exception of Oman) said they decided to intervene against the Houthis in Yemen at the request of Hadi's government.[222][223][224] King Salman of Saudi Arabia declared the Royal Saudi Air Force to be in full control of Yemeni airspace within hours of the operation beginning.[225] The airstrikes were aimed at hindering the Houthis' advance toward Hadi's stronghold in southern Yemen.[226]

Al Jazeera reported that Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, a Houthi commander appointed in February as President of the Revolutionary Committee, was injured by an airstrike in Sanaʽa on the first night of the campaign.[227]

After the launch of Operation Decisive Storm, Saudi Arabia along with the UAE used lobbying in an attempt to rally the international community to their cause.[159]

Reuters reported that planes from Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Sudan, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Bahrain had also taken part in the operation.[29] Saudi Arabia requested that Pakistan commit forces as well, but Pakistan's parliament officially voted to remain neutral.[228] However, Pakistan agreed to provide support in line with a United Nations Security Council resolution, dispatching warships to enforce an arms embargo against the Houthis.[86][229]

On 21 April 2015, the bombing campaign was officially declared over, with Saudi officials saying they would begin Operation Restoring Hope as a combination of political, diplomatic, and military efforts to end the war.[230] Even still, airstrikes continued against Houthi targets, and fighting in Aden and Ad Dali' went on.[231]

The United Arab Emirates claimed to take an active role against fighting AQAP and IS-YP presence in Yemen through a partnership with the United States. In an Op-Ed in The Washington Post, Yousef Al Otaiba, the UAE ambassador to the United States, described that the intervention has reduced AQAP presence in Yemen to its weakest point since 2012 with many areas previously under their control liberated.[232] The ambassador claimed that more than 2,000 militants have been removed from the battlefield, with their controlled areas now having improved security and a better delivered humanitarian and development assistance such as to the port city of Mukalla and other liberated areas.[232]

An Associated Press investigation outlined that the military coalition in Yemen actively reduced AQAP in Yemen without military intervention, instead of by offering them deals and even actively recruiting them in the coalition because "they're considered exceptional fighters".[233] UAE Brigadier General Musallam Al Rashidi responded to the accusations by stating that Al Qaeda cannot be reasoned with and cited that they killed many of his soldiers.[234] The UAE military stated that accusations of allowing AQAP to leave with cash contradict their primary objective of depriving AQAP of its financial strength.[235] The notion of the coalition recruiting or paying AQAP has been thoroughly denied by the United States Pentagon with Colonel Robert Manning, spokesperson of the Pentagon, calling the news source "patently false".[236] The governor of Hadramut Faraj al-Bahsani, dismissed the accusations that Al Qaeda has joined with the coalition rank, explaining that if they did there would be sleeper cells and that he would be "the first one to be killed". According to The Independent, AQAP activity on social media as well as the number of terror attacks conducted by them has decreased since the Emirati intervention.[235]

On 13 July 2020, the UK Ministry of Defence logged more than 500 Saudi air raids in possible breach of international law in Yemen. These figures were revealed a few days after the UK government decided to resume the arms sales to Saudi Arabia, which could be used in the Yemen war, just over a year after the court of appeal ruled them unlawful. It justified resuming the arms sales stating that only isolated incidents without any pattern have occurred.[237]

In March 2019, the United States Congress voted to end US support to the Saudi war effort;[238] however, US President Donald Trump vetoed it.[239] His successor, President Joe Biden, announced a freeze on arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE in January 2021.[240] He also declared that he would end American support for the Saudi coalition.[241] On 4 February 2021, Biden announced an end to the US support for Saudi-led operations in Yemen.[242] As of 13 April 2021, arms sales to the UAE have not been stopped, while sales to Saudi Arabia continued to be paused.[243] However, the details of the end of American involvement in the war have yet to be released.[244]

In August 2020, confidential Saudi documents revealed the kingdom's strategy in Yemen. The 162 pages of classified Saudi documents dates back prior to 2015. The pages showed the kingdom's inaction in stopping the Houthis from capturing Sanaa, despite Saudi intelligence reports. The records also exposed that Saudi Arabia had worked to hamper the rebuilding projects commissioned by Germany and Qatar in Saada. This happened after the fighting between the two warring camps came to a halt due to a ceasefire.[245]

Arab League

[edit]In Egypt, the Yemeni foreign minister called for an Arab League military intervention against the Houthis.[222] Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi floated the idea of a unified military force.[246]

The Arab League announced the formation of a unified military force to respond to conflict in Yemen and Libya.[247]

US role

[edit]Since the mid-2000s, the United States has been carrying out targeted killings of Al-Qaeda militants in Yemen, although the U.S. government generally does not confirm involvement in specific attacks conducted by unmanned aerial vehicles as a matter of policy. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism documented 415 strikes in Pakistan and Yemen by 2015 since the September 11 attacks, and according to the organization's estimates, between 423 and 962 deaths are believed to have been civilians. Michael Morell, former deputy director of the CIA, claims the numbers were significantly lower.[248]

During the civil war in Yemen, drone strikes have continued, targeting suspected leaders of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Ibrahim al-Rubeish and Nasser bin Ali al-Ansi, two leading AQAP figures, were killed by U.S. drone strikes in the vicinity of Mukalla in 2015.[249][250] Approximately 240 suspected AQAP militants have been killed by American drone strikes since the civil war began.[251]

On 2013, Radhya Al-Mutawakel and Abdelrasheed Al-Faqih, Directors of Mwatana, published a joint report with Open Society Foundations titled 'Death by Drone', detailing evidence of civilian casualties and damage to civilian objects in nine US drone strikes.[252]

The United States supplied intelligence and logistical support, including aerial refueling and search and rescue for downed coalition pilots.[253] Also, US revved arms sales to coalition countries.[254] In January 2016, Saudi Arabia's foreign minister stated: US and UK military officials were in the command and control center responsible for the Saudi-led airstrikes in Yemen and had access to the list of targets but were not involved in the selection of targets.[255][256][257]

Islamic State presence and operations

[edit]The Islamic State (IS) has proclaimed several provinces in Yemen and has urged its adherents to wage war against the Houthi movement, as well as against Zaydis in general.[258] ISIS militants have conducted bombing attacks in various parts of the country, particularly against mosques in Sanaʽa.[259][260]

On 6 October 2015, IS militants conducted a series of suicide bombings in Aden that killed 15 soldiers affiliated with the Hadi-led government and the Saudi-led coalition.[261] The attacks were directed against the al-Qasr hotel, which had been a headquarters for pro-Hadi officials, and also military facilities.[261] Yemeni officials and UAE state news agency declared that 11 Yemeni and 4 United Arab Emirates soldiers were killed in Aden due to 4 coordinated Islamic State suicide bombings. Prior to the claim of responsibility by the Islamic State, UAE officials blamed the Houthis and former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, for the attacks.[261]

Humanitarian situation

[edit]CNN reported on 8 April 2015 that almost 10,160,000 Yemenis were deprived of water, food, and electricity as a result of the conflict. The report also added per source from UNICEF officials in Yemen that within 15 days, some 100,000 people across the country were dislocated, while Oxfam said that more than 10 million Yemenis did not have enough food to eat, in addition to 850,000 half-starved children. Over 13 million civilians were without access to clean water.[262]

A medical aid boat brought 2.5 tonnes of medicine to Aden on 8 April 2015.[263] A UNICEF plane loaded with 16 tonnes of supplies landed in Sanaa on 10 April.[264] The United Nations announced on 19 April 2015 that Saudi Arabia promised to provide $273.7 million in emergency humanitarian aid to Yemen. The UN appealed for the aid, saying 7.5 million people had been affected by the conflict and many were in need of medical supplies, potable water, food, shelter, and other forms of support.[265]

On 12 May 2015, Oxfam warned that the five days a humanitarian ceasefire was scheduled to last would not be sufficient to fully address Yemen's humanitarian crisis.[266] It has also been said that the Houthis are collecting a war tax on goods. The political analyst Abdulghani al-Iryani affirmed that this tax is: "an illegal levy, mostly extortion that is not determined by the law and the amount is at the discretion of the field commanders".[267]

As the war dragged on through the summer and into the fall, things were made far worse when Cyclone Chapala, the equivalent of a category 2 Hurricane,[268] made landfall on 3 November 2015. According to the NGO Save the Children, the destruction of healthcare facilities and a healthcare system on the brink of collapse as a result of the war will cause an estimated 10,000 preventable child deaths annually. Some 1,219 children have died as a direct result of the conflict thus far. Edward Santiago, the NGO's Yemen director, asserted in December 2016:[269]

Even before the war tens of thousands of Yemeni children were dying of preventable causes. But now, the situation is much worse and an estimated 1,000 children are dying every week from preventable killers like diarrhea, malnutrition, and respiratory tract infections.

In March 2017, the World Food Program reported that while Yemen was not yet in a full-blown famine, 60% of Yemenis, or 17 million people, were in "crisis" or "emergency" food situations.[270]

In June 2017, a cholera epidemic resurfaced which was reported to be killing a person an hour in Yemen by mid June.[271] News reports in mid June stated that there had been 124,000 cases and 900 deaths and that 20 of the 22 provinces in Yemen were affected at that time.[272] UNICEF and WHO estimated that, by 24 June 2017, the total cases in the country exceeded 200,000, with 1,300 deaths.[273] 77.7% of cholera cases (339,061 of 436,625) and 80.7% of deaths from cholera (1,545 of 1,915) occurred in Houthi-controlled governorates, compared to 15.4% of cases and 10.4% of deaths in government-controlled governorates, since Houthi-controlled areas have been disproportionately affected by the conflict, which has created conditions conducive to the spread of cholera.[274]

On 7 June 2018, it was reported that the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) had pulled 71 of its international staff out of Yemen, and moved the rest of them to Djibouti, with some 450 ICRC employees remaining in the country. The partial evacuation measure came on the eve of an ICRC worker, a Lebanese national, being killed on 21 April by unknown gunmen in the southwestern city of Taiz. The ICRC stated, "our current activities have been blocked, threatened and directly targeted in recent weeks, and we see a vigorous attempt to instrumentalize our organization as a pawn in the conflict." In light of the serious security deterioration for ICRC personnel, the international organization has called for all parties of the conflict "to provide it with concrete, solid and actionable guarantees so that it can continue working in Yemen." Since the beginning of the conflict, more than 10,000 people have been killed and at least 40,000 wounded, mostly from air raids.[275]

The International Rescue Committee stated in March that at least 9.8 million people in Yemen were acutely in need of health services. The closure of Sanaʽa and Riyan airports for civilian flights and the limited operation of civilian airplanes in government-held areas, made it impossible for most to seek medical treatment abroad. The cost of tickets provided by Yemenia, Air Djibouti and Queen Bilqis Airways, also put traveling outside Yemen out of reach for many.[276][277]

The United Nations Development Programme published a report in September 2019 that said if the war continues, Yemen will become the poorest country in the world, with 79% of the population living below the poverty line and 65% in extreme poverty by 2022.[278]

On 3 December 2019, the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, Amnesty International released a report highlighting how the almost 5-year old Yemen war has left millions of people living with disabilities and excluded from medical attention. The armed conflict led by Saudi Arabia and UAE as part of the former's coalition in the Arab nation against Houthis and terror groups, has given birth to the worst humanitarian crisis, as stated by the United Nations.[279]

Humanitarian aid provided to Houthi-controlled Yemen will be scaled-down in March 2020 because donors doubt if it's actually reaching the people in need, UN official said.[280]

In June 2020, the UNHCR said that following more than five years of war in Yemen, more than 3.6 million people have been forced to flee their homes, while 24 million are in dire need of aid. The group also informed that a significant gap in funding has been recorded with only US$63 million received thus far, while at least US$211.9 million is needed to run the operations in 2020.[281]

On 2 July 2020, Human Rights Watch reported that detainees at Aden's Bir Ahmed facility were facing serious health risks from the rapidly spreading coronavirus pandemic. The informal detention facility, controlled by Yemeni authorities affiliated with the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, is grossly overcrowded and was deprived of health care facilities.[282]

The World Food Programme (WFP) projected in March 2021 that if the Saudi-led blockade and war continues, more than 400,000 Yemeni children under 5 years old could die from acute malnutrition before the end of the year as the blockade devastates nation.[283][284][285]

War crime accusations

[edit]

According to Farea Al-Muslim, direct war crimes have been committed during the conflict; for example, an IDP camp was hit by a Saudi airstrike, while Houthis have sometimes prevented aid workers from giving aid.[286] The UN and several major human rights groups discussed the possibility that war crimes may have been committed by Saudi Arabia during the air campaign.[287][288]

British researcher Alex de Waal wrote that the "responsibility for Yemen goes beyond Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to London and Washington. Britain has sold at least £4.5 billion in arms to Saudi Arabia and £500 million to the UAE since the war began. The US role is even bigger: Trump authorized arms sales to the Saudis worth $110 billion last May. Yemen will be the defining famine crime of this generation, perhaps this century."[289]

In August 2018, a report by UN experts said all parties to the conflict may have committed war crimes, including the governments of Yemen, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, and the Houthi movement. The UN described the conflict as the world's worst humanitarian crisis. The report documented 6,475 deaths in the conflict, but estimated the true number was significantly higher. The report criticized Saudi-led airstrikes and accused parties of unlawful violations such as "deprivation of the right to life, arbitrary detention, rape, torture, enforced disappearances and child recruitment".[290]

In February 2020, British law firm Stoke White appealed the authorities in Britain, the U.S., and Turkey to arrest senior officials from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for allegedly carrying out war crimes and torture in Yemen. The complaints were lodged under the provision of 'universal jurisdiction', wherein the nations must probe breaches of the Geneva Convention for possible war crimes.[291]

In March 2020, Human Rights Watch accused Saudi military forces and Saudi-backed Yemeni forces of carrying out abuse of Yemeni civilians in the country's eastern province of al-Mahrah. They accused them arbitrarily arresting, torturing, and illegally transferring detainees to the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The report documented 16 cases of arbitrary detention and five cases of detainees who had been transferred illegally to Saudi Arabia.[292][293] According to a report from May 2020 by Yemeni human rights group Mwatana, since May 2016, more than 1,600 cases of arbitrary detentions, 770 forced disappearances, 344 cases of torture and at least 66 deaths in unofficial prisons have been documented. The report stated that Houthis were responsible for most abuses. It blamed them for 350 forced disappearances, 138 incidents of torture, and 27 deaths in detention, while UAE-backed forces, including the Southern Transitional Council, were responsible for 327 disappearances, 141 cases of torture, and 25 deaths in detention. The report blamed forces loyal to the Saudi-backed Yemeni government for 65 cases of torture and over 24 deaths.[294]

An investigation led by Sky News reported that on 12 July 2020, an air-strike in Northern Yemen, reportedly carried out by the Saudi-led coalition, hit a family home, killing six children and three women. The investigators found fragments of the bomb and some of the shrapnel which seemed to be the part of a GBU-12, 500 lb fin-guided bomb, manufactured in the US. The Joint Incidents Assessment Team is still investigating the attack.[295]

The United Nations has accused both sides of the conflict of using child soldiers. In August 2018, the UN reported that two-thirds of child soldiers in Yemen fought for the Houthis. The report documented 800 cases of child soldiers in 2017.[296][297] In December 2018, The New York Times reported that Saudi Arabia had hired Child Soldiers from Sudan (especially from Darfur), and Yemen to fight against Houthis. They reported that as many as 14,000 Sudanese militiamen were fighting in the war, many of them children.[298][299][300] In March 2019, it was reported that British SAS special forces had allegedly been involved in training child soldiers in Yemen.[301] In March 2019, Al Jazeera reported that Saudi Arabia recruited Yemeni children to guard the Saudi Arabia-Yemen border against Houthis.[297] In January 2022, the UN reported that 1,406 child soldiers recruited by the Houthis had died on the battlefield in 2020 and 562 had died between January and May 2021.[302]

In February 2022, unknown armed men kidnapped five United Nations personnel in southern Yemen as they were returning to Aden after a field tour. According to Russell Geekie, a spokesman for the top UN official in Yemen, the crew was kidnapped on Friday, 11 February 2022, in the Abyan governorate.[303] In August 2023, the kidnapped United Nations personnel were released.[304]

Impact on citizens

[edit]Children and women

[edit]

According to UN estimates, the war has directly caused the death of over 3,000 children as of December 2020[update]; while indirect causes of the war (lack of food, health and infrastructure) have led to additional deaths.[305] The UN estimates that at the end of 2021, 70% of all the casualties of the war (around 259,000) are children under five.[306][better source needed]

Yemeni refugee women and children are extremely susceptible to smuggling and human trafficking.[307] NGOs report that vulnerable populations in Yemen were at increased risk for human trafficking in 2015 because of ongoing armed conflict, civil unrest, and lawlessness. Migrant workers from Somalia who remained in Yemen during this period suffered from increased violence, and women and children became most vulnerable to human trafficking. Prostitution on women and child sex slaves is a social issue in Yemen. Citizens of other gulf states are beginning to be drawn into the sex tourism industry. The poorest people in Yemen work locally and children are commonly sold as sex slaves abroad. While this issue is worsening, the plight of Somalis in Yemen has been ignored by the government.[308] Emphasizing the dire humanitarian needs for about 23.4 million people, UNFPA reported the lack of access to sexual and reproductive health and protection services, and exposure to death in pregnancy and childbirth and life-threatening violence. An increase in child marriage as a coping mechanism by impoverished families as the conflict continues was also reported.[309]

Children are recruited between the ages of 13 and 17, and as young as 10 years old into armed forces despite a law against it in 1991. The rate of militant recruitment in Yemen increases exponentially. According to an international organization, between 26 March and 24 April 2015, armed groups recruited at least 140 children.[310] According to the New York Times report, 1.8 million children in Yemen are extremely subject to malnutrition in 2018.[311]

Both the Saudi-led coalition and the Houthis were blacklisted by the UN over the deaths of children during the war. In 2016 Saudi Arabia was removed from the list after alleged pressure from Gulf countries who threatened to withdraw hundreds of millions of dollars in assistance to the UN, the decision was criticized by human rights groups and the coalition added again in 2017 and was accused of killing or injuring 683 children, and attacking many of schools and hospitals in 38 confirmed attacks, while the Houthis were accused of being responsible for 414 child casualties in 2016.[312][313][314] On 16 June 2020, the United Nations removed the Saudi-led coalition fighting in Yemen war from an annual blacklist of parties violating children's rights. The decision was taken despite the UN finding that the coalition operations killed or injured nearly 222 children in Yemen, in 2019. The Saudi-led coalition's removal from the blacklist leaves Yemeni children vulnerable to future attacks.[315]

In mid-May 2019, a series of Saudi/Emirati-led airstrikes hit Houthi targets on the outskirts of Sanaa. One of the airstrikes destroyed several homes, killing five civilians and injuring more than 30. According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, while 4,800 of about 7,000 civilian fatalities have been caused by the Saudi-led coalition since 2016, the Houthis are accountable for 1,300 civilian deaths.[316]

According to a 2019 report by UNICEF, two million children had dropped out of school in Yemen since the conflict began in March 2015. The education of other 3.7 million children was endangered because teachers had not been paid since 2017.[317]

On 9 October 2019, children's advocacy group, Save the Children warned of a significant rise in cholera cases in northern Yemen. The crisis caused by increase in fuel shortages has affected several thousand children and their families.[318]

Health

[edit]The Yemeni civil war has often been referred to as the "world's forgotten war".[319][320] In 2018, the United Nations warned that 13 million Yemeni civilians face starvation in what it says could become "the worst famine in the world in 100 years."[321] The UN estimates that the war caused an estimated 230,000 deaths by December 2020, of which 130,000 were from indirect causes which include lack of food, health services and infrastructure.[305] Earlier estimates from 2018 from Save the Children estimated that 85,000 children have died due to starvation in the three years prior.[322]

Between October 2016 and August 2019, over 2,036,960 suspected cholera cases were reported in Yemen, including 3,716 related deaths (fatality rate of 0.18%).[323]

The seasonal flu virus in Yemen has claimed more than 270 lives since October 2019. Poor medical facilities and widespread poverty in Yemen due to the war waged by Saudi-led coalition and Houthis have led to the deaths of many infected patients in their homes.[324]

Between April and July 2020, research showed that there was a peak in daily excess burial rates of approximately 1500, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[325]

The overall disease surveillance in Yemen was also affected by the armed conflict. The disease early warning system was fragmented, with the government without control of the system in Houthis controlled areas and vice versa.[326][327]

The UN estimated that by the end of 2021, the conflict in Yemen had claimed more than 377,000 lives, and 70% of deaths were children under age 5.[146][130]

Religious minorities

[edit]The US government estimates that religious minorities in Yemen constitute less than 1% of the population. They are categorized into four groups including Baha’is, Jews, Christians and Hindus. The Houthi movement has been said to be intolerant towards religious minorities. It was claimed that Houthis attachement to their own practices has led to a discriminatory stance against other types of faiths present in territories that are under their control. The Baha’i International Community stated that a number of Baha’is were imprisoned by the Houthi for religious reasons.[328]

In the province of Al-Bayda, AQAP was responsible for the execution of four people on January 10, 2019. The justification given related to their atheist beliefs.[328]

As of March 2020, the Jewish Cemetery in Aden was destroyed; as of April 2020, the fate of the last 50 Jews in Yemen was reported to be unknown.[329] On 13 July 2020 it was reported that the Houthi Militia is capturing the last Jews of Yemen of the Kharif District.[330] On 16 July 2020, five Jews were allowed to leave Yemen by the Houthi, leaving 33 Jews in the country.[331] In July 2020, the Mona Relief reported on their website that as of 19 July 2020, of the Jewish population in Yemen there were only a "handful" of Jews in Sanaa.[332] On 29 March 2021, the Iranian-backed Houthi government deported the last remaining Yemenite Jews to Egypt, ending the continuous presence of a community that dated back to antiquity.[333]

Education

[edit]The civil war in Yemen severely impacted and degraded the country's education system. The number of children who are out of school increased to 1.8 million in 2015–2016 out of more than 5 million registered students, according to the 2013 statistics released by the Ministry of Education.[334] Moreover, 3600 schools are directly affected; 68 schools are occupied by armed groups, 248 schools have severe structural damage, and 270 are used to house refugees. The Yemen government has not been able to improve this situation due to limited authority and manpower.

Some of the education system's problems include: not enough financial resources to operate schools and salaries of the teachers, not enough materials to reconstruct damaged schools, and lack of machinery to print textbooks and provide school supplies. These are caused by the unstable government that cannot offer enough financial support since many schools are either damaged or used for other purposes.[335]

Despite warfare and destruction of schools, the education ministry was able to send teams to oversee primary and secondary schools' final exam in order to give students 15–16 school year certificates.[334] Currently, UNICEF is raising money to support students and fix schools damaged by armed conflicts.

Residential condition

[edit]The Yemeni quality of life is affected by the civil war and people have suffered enormous hardships. Although mines are banned by the government, Houthi forces placed anti-personnel mines in many parts of Yemen including Aden.[336] Thousands of civilians are injured when they accidentally step on mines; many lose their legs and injure their eyes. It is estimated that more than 500,000 mines have been laid by Houthi forces during the conflict. The pro-Hadi Yemen Army was able to remove 300,000 Houthi mines in recently captured areas, including 40,000 mines on the outskirts of Marib province, according to official sources.[337]

In addition, the nine-country coalition led by Saudi Arabia launched many airstrikes against Houthi forces; between March 2015 and December 2018 more than 4,600 civilians have been killed and much of the civilian infrastructure for goods and food production, storage, and distribution has been destroyed.[338][339] Factories have ceased production and thousands of people have lost their jobs. Due to decreased production, food, medicines, and other consumer staples have become scarce. The prices of these goods have gone up and civilians can no longer afford them for sustenance.[340]

Refugees

[edit]Djibouti, a small country in the Horn of Africa across the Bab-el-Mandeb strait from Yemen, has received an influx of refugees since the start of the campaign.[341][342][343] Refugees also fled from Yemen to Somalia, arriving by sea in Somaliland and Puntland starting 28 March.[344][345] On 16 April 2015, 2,695 refugees of 48 nationalities were reported to have fled to Oman in the past two weeks.[346]

According to Asyam Hafizh, an Indonesian student who was studying in Yemen, Al-Qaeda of Yemen has rescued at least 89 Indonesian civilians who were trapped in the conflict. Later on he arrived in Indonesia and he told his story to local media.[347] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported in August 2015 that a total of almost 100,000 people fled Yemen, especially to regional countries, like Saudi Arabia and Djibouti.[348] In September 2016, UNHCR estimated displacement of 2.4 million Yemenis within the country and 120,000 seeking asylum.[349]

In 2018, 500 refugees fleeing the civil war in Yemen came to Jeju Island, causing unease among the residents of Jeju Island.[350][351][352][353][354][355]

According to the International Organisation for Migration, despite the dangerous situation, nearly 150,000 migrants from Ethiopia arrived in Yemen in 2018, most of whom were on their way to Saudi Arabia in search of employment.[356]

In October 2019, Kuwait donated $12 million to the UNHCR to support its humanitarian programs in Yemen. Salvatore Lombardo, Chief of Staff at office of the UNHCR, said that the donation will be allocated to address the issues of Yemen's internally displaced persons (IDPs).[357]

Evacuation of foreign nationals from Yemen

[edit]

The Royal Saudi Navy evacuated diplomats and United Nations staff from Aden to Jeddah on 28 March 2015 as the Houthis targeted the city.[358]

Pakistan dispatched two special PIA flights to evacuate from Aden some 500 stranded Pakistanis on 29 March 2015.[359] Several UN staff members and Arab diplomats were also evacuated following the airstrikes.[360]

The Indian government responded by deploying ships and planes to Yemen to evacuate stranded Indians. India began evacuating its citizens from Aden on 2 April by sea.[361] An air evacuation of Indian nationals from Sanaa to Djibouti started on 3 April, after the Indian government obtained permission to land two Airbus A320s at the Houthi-controlled airport.[362] The Indian Armed Forces carried out rescue operation codenamed Operation Raahat and evacuated more than 4640 overseas Indians in Yemen along with 960 foreign nationals of 41 countries.[363] The Sanaa air evacuation ended on 9 April 2015 while the Aden evacuation by sea ended on 11 April 2015.[364] The United States did not undertake an evacuation of private U.S. citizens from the country,[365] but some Americans (as well as Europeans) took part in an evacuation organized by the Indian government.[366]

A Chinese missile frigate docked in Aden on 29 March to evacuate Chinese nationals.[367] The ship reportedly deployed soldiers ashore on 2 April to guard the evacuation of civilians from the city.[368] Hundreds of Chinese and other foreign nationals were safely evacuated aboard the frigate in the first operation of its kind carried out by the Chinese military.[369] The Philippines announced that 240 Filipinos that had grouped in Sanaa were evacuated across the Saudi border to Jizan, before boarding flights to Riyadh and then to Manila.[370]

The Malaysian government deployed two Royal Malaysian Air Force C-130 aircraft to evacuate their citizens from the safe airports in Djibouti and Dubai.[371] From Aden they were recuperated first by sea,[372] and there were many in Hadhramaut Governorate.[371] On 15 April, around 600 people were evacuated to Malaysia, also comprising citizens of other Southeast Asian countries such as 85 Indonesians, 9 Cambodians, 3 Thais and 2 Vietnamese.[372]

The Indonesian Air Force also sent a Boeing 737-400 and a chartered aircraft to evacuate Indonesian citizens. Indonesians remained in Tarim, Mukallah, Aden, Sanaa and Hudaydah.[373]

The Ethiopian Foreign Ministry said it would airlift its citizens out of Yemen if they requested to be evacuated.[374] There were reportedly more than 50,000 Ethiopian nationals living and working in Yemen at the outbreak of hostilities.[375] More than 3,000 Ethiopians registered to evacuate from Yemen, and as of 17 April, the Ethiopian Foreign Ministry had confirmed 200 evacuees to date.[376]

Throughout April Russian military forces evacuated more than 1,000 people of various nationalities, including primarily Russian citizens, on at least nine flights to Chkalovsky Airport, a military air base near Moscow. In early April around 900 had come from Houthi-controlled Sanaa, and the balance from Aden.[377]

The UNSC Resolution 2216 was then agreed on 14 April 2015.[378]

United Nations response

[edit]The United Nations has been closely following the Yemeni war since its beginning. It has looked for solutions to alleviate security concerns in Yemen and stop the Hadi-Houthi conflict from escalating. The Peace and National Partnership Agreement in 2014 was its final attempt at quelling the dispute before it transformed into a war.[157]

The United Nations representative Baroness Amos, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, said on 2 April 2015 that she was "extremely concerned" about the fate of civilians trapped in fierce fighting, after aid agencies reported 519 people killed and 1,700 injured in two weeks. The UN children's agency reported 62 children killed and 30 injured and also children being recruited as soldiers.[379]

Russia called for "humanitarian pauses" in the coalition bombing campaign, bringing the idea before the United Nations Security Council in a 4 April emergency meeting.[380] However, Saudi Arabia's ambassador to the United Nations questioned whether humanitarian pauses would be the best way of delivering humanitarian assistance.[381]

On March 22, 2015, the UN declared its recognition of Hadi as the sole legitimate president and encouraged the peaceful resolution of the dispute. A few days later, Saudi Arabia intervened military with an air strike.[157]

On 14 April 2015, the United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution placing sanctions on Abdul-Malik al-Houthi and Ahmed Ali Saleh, establishing an arms embargo on the Houthis, and calling on the Houthis to withdraw from Sanaʽa and other areas they seized.[382] The Houthis condemned the UN resolution and called for mass protests.[383]

Jamal Benomar, the UN envoy to Yemen who brokered the deal that ended Ali Abdullah Saleh's presidency during the 2011–12 revolution, resigned on 15 April.[384] Mauritanian diplomat Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, formerly the head of the UN's Ebola response mission, was confirmed as the new UN Envoy to Yemen on 25 April.[385] The Panel of Experts on Yemen mandated by the Security Council, UN submitted a 329-page report to the latter's president on 26 January 2018 denouncing the UAE, the Yemeni government and the Houthis for torturing civilians in the Yemeni conflict.[386]

In December 2018, UN-sponsored talks between the Houthis and the Saudi-backed government were expected to start. The UN also started using its jets to carry wounded Houthi fighters out of the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, to Oman, paving the way for planned peace talks after nearly four years of civil war.[387]

According to United Nations, more than 3.6 million Yemenis have been displaced in the 5-year-old conflict. The World Food Programme, which feeds more than 12 million Yemenis needs more funding to continue the ongoing operations and ramp back up operations in the north. Without funding, 30 of 41 major aid programmes in Yemen would close in the next few weeks.[388]

On 27 September 2020, the United Nations announced that the Iran-backed Houthi rebels and the Hadi government supported by the Saudi-led military coalition, agreed to exchange about 1,081 detainees and prisoners related to the conflict as part of a release plan reached in early 2020. The deal stated the release of 681 rebels along with 400 Hadi government forces, which included fifteen Saudis and four Sudanese. The deal was finalized after a week-long meeting held in Glion, Switzerland, co-chaired by UN Special Envoy for Yemen, Martin Griffiths.[389] The prisoner-swap deal was done by the UN during the 2018 peace talks in Sweden which produced the Stockholm Agreement. The latter consisted of three major documents. The first one suggested the formation of a committee; the second called for the exchange of prisoners; the third aimed at creating the United Nations Mission to support the al-Hodeida Agreement (UNMHA).[157] Both parties agreed on several measures including the cease-fire in the strategic port city of Hodeida. A prisoner swap deal was made as part of the 2018 peace talks held in Sweden. However, the implementation of the plan clashed with military offensives from Houthis and the Saudi-led coalition, which aggravated the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, leaving millions suffering medical and food supply shortages.[389]

On 7 October 2022, the UN Human Rights Council adopted, without a vote, a futile resolution on Yemen that failed to establish a credible independent and impartial monitoring and accountability mechanism. The adoption came a year after the same body rejected the renewal of the mandate for the Group of Eminent Experts (GEE), an international, impartial, and independent body established by the Human Rights Council in 2017 that reported on rights violations and abuses in Yemen.[390]

Peace process

[edit]The Yemeni Civil War, which began in 2014, has been one of the most heavy conflicts in history, and caused a severe humanitarian crisis. In recent years, however, there have been several efforts to achieve a peaceful resolution and bringing stability to the country.[391]

One of the most important developments in the peace process was the Stockholm Agreement, which was reached in December 2018 between the conflicting parties, the government of Yemen and the Houthi rebels. This agreement focused on implementing a ceasefire in the city of Hodeida and the areas surrounding the city. The agreement also focused on the redeployment of forces, and addressing humanitarian concerns. The agreement was seen as a significant step to alleviate the suffering of the Yemeni people and for further negotiations.[392]

Subsequently, there have been multiple rounds of talks and negotiations facilitated by the United Nations. These discussions have covered a comprehensive political solution, prisoner exchanges and the establishment of a transitional government. The main goal has been to address the causes of the conflict, foster national reconciliation and restore security and stability in Yemen.[393]

Another important development in the peace process was the Riyadh Agreement, between the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) in November 2019. This agreement aimed to resolve power struggles in southern Yemen by establishing a power-sharing arrangement between the two parties. It was seen as a significant step towards achieving a unified Yemen and an important component of the broader peace process.[394] While progress has been made, the road to peace in Yemen remains challenging due to ongoing clashes, political divisions and regional rivalries. Additionally, the humanitarian situation in Yemen remains dire, with millions of people in urgent need of assistance.[395]

The Wall Street Journal reported in March 2023 that Iran agreed to halt all military support to Houthis and abide by the UN arms embargo, as part of a Chinese-brokered Iran-Saudi rapprochement deal. The agreement was concluded with the objective to put pressure on Houthi militants to end the conflict through negotiated settlement; with Saudi and US officials describing the concomitant Iranian behaviour as a "litmus test" for the endurance of the Chinese-brokered détente. The agreement was concluded in the background of Iran's international isolation following the escalation of its nuclear program, an ongoing crackdown on Mahsa Amini protests and its support to Russian invasion of Ukraine.[396][397][398][399]

Other developments

[edit]Armed Houthis ransacked Al Jazeera's news bureau in Sanaʽa on 27 March 2015, amid Qatar's participation in the military intervention against the group. The Qatar-based news channel condemned the attack on its bureau.[400] On 28 March, Ali Abdullah Saleh stated neither he nor anyone in his family would run for president, despite recent campaigning by his supporters for his son Ahmed to seek the presidency. He also called on Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi to step down as president and said new elections should be held.[401]

Rumors about Saleh's whereabouts swirled during the conflict. Foreign Minister Riad Yassin, a Hadi loyalist, claimed on 4 April that Saleh left Yemen aboard a Russian aircraft evacuating foreign nationals from Sanaa International Airport.[402] Later in the month, Saleh reportedly asked the Saudi-led coalition for a "safe exit" for himself and his family, but the request was turned down.[403]

King Salman reshuffled the Saudi cabinet on 28 April, removing Prince Muqrin as his designated successor. The Saudi royal palace said Muqrin had asked to step down, without giving a reason, but media speculation was that Muqrin did not demonstrate sufficient support for the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen.[404] A spokesman for Yemen's exiled government told Reuters on 29 April that the country would officially seek membership in the Gulf Cooperation Council.[405] Media reports have noted that the civil war has reached nearly all of Yemen, with one notable exception being the remote Indian Ocean archipelago of Socotra,[406] where the war spread due to the South Yemen insurgency in 2017.[407]

On 30 September 2019, Houthi rebels released 290 Yemeni prisoners in a move, stated by the United Nations as a revival of peace process, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) said.[408]

In September 2020, the United Nations announced a swap of "1081 conflict-related prisoners" between the two opponents, including Saudi and Sudanese troops fighting for the Saudi-led coalition.[409] In October 2020, two American hostages Sandra Loli and Mikael Gidada who had been captives for 16 months, were freed by the Houthi rebels in exchange for releasing 240 former Houthi combatants in Oman.[410]

In January 2021, the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced his intentions of declaring the Houthi movement in Yemen a "foreign terrorist organization". Under the plan, the three leaders of the Houthis, known as Ansarallah, were to be listed as Specially Designated Global Terrorists. However, it induced a fear among the diplomats and aid groups that the move would cause issues in the peace talks and in delivering aid to the Yemen crisis.[411]

Although the United Arab Emirates had announced plans in 2019 to vacate Yemen and withdraw all its troops, the Arab nation continued to maintain its presence for strategic objectives. Reports in May 2021 revealed that the Emirates was building a mysterious airbase on Yemen's Mayun Island in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Satellite images revealed that the construction work to build a 1.85 km (6,070 ft) runway, along with three hangars, on the island was completed on 18 May 2021. Military officials of the Yemeni government said that the UAE was transporting military equipment, weapons and troops to Mayun Island through ships. The island was considered a strategic location for anyone who controls it, offering power for operations into the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea and East Africa, and for easily launching airstrikes into Yemen's mainland.[412]

On 7 October 2021, Bahrain, along with Russia and other members of the UN human rights council, opposed the council's investigations into the war crimes in Yemen. The members narrowly voted to reject the Netherlands' resolution to give another two years to the independent investigators to continue the probe to monitor atrocities in the Yemen war. In the past, independent investigators concluded that potential war crimes have been committed by all sides. An ally of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia is not a voting member of the council, but rights activists said the Kingdom heavily lobbied against the resolution.[413]

On 20 March 2022, the United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross reported that the Yemeni government and the Houthis agreed to release 887 detainees, following 10 days of negotiations in Switzerland. Both parties also agreed to visitation rights in detention facilities and likely more prisoner swaps in the near future. Hans Grundberg, the UN's special envoy for Yemen said that things are finally moving "in the right direction" toward a resolution of the conflict. This came after the recent Saudi-Iranian rapprochement mediated by China a week earlier.[414]

Environmental impact

[edit]Water

[edit]Yemen is facing one of the world's worst Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) crises. The lack of governance has left Yemen without a viable water supply. Poor sanitation and the lack of clean water has had a deteriorating effect on the health of Yemenis, which is apparent through the increasing cases of cholera in Yemen since 2015. The entire country has been affected by a water shortage and the price of drinking water has more than doubled. Drinking water has become unaffordable for most Yemenis. The problem in Yemen is widespread, thus making it difficult to prevent the problem from escalating because it is hard to supply everyone on a regular basis.

The Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa at UNICEF, Geert Cappelaere, has explained that the fuel shortages in Yemen have deepened the water and health crisis. The water pumping stations in Yemen have been jeopardized as they are quickly running out of fuel and over 3 million people are dependent on these water pumps which have been established through public networks. The ICRC has been working closely with vulnerable people where the resources are limited but aim to prevent the water crisis from worsening by buying 750,000 liters of diesel to provide clean water for people living in Yemen. Already a scarce commodity, the amount of water withdrawn from wells in 2016 reached unsustainable levels. The ICRC has also been working carefully with local authorities to provide water to 330,000 people in Aden. They have also installed wells nearby Aden to provide water to the neighborhood when they are experiencing water shortages.

Water resources have been used by both sides during the war as a tactic during the conflict. Unlike other countries in the Middle East, Yemen has no rivers to depend on for water resources. In 2017, 250,000 people of Taiz's total population of 654,330 were served by public water supply networks. As a result of the ongoing conflict NGO's have struggled to reach the sanitation facilities due to security issues. Since the aerial bombardment, Taiz has been left in a critical situation as the current water production is not sufficient for the population.

Water availability in Yemen has decreased.[415] Water scarcity with an intrinsic geographical formation in highlands and limited capital to build water infrastructures and provision service caused a catastrophic water shortage in Yemen. Aquifer recharge rates are decreasing while salt water intrusion is increasing.[416] After the civil war began in 2015, the water buckets were destroyed significantly and price of water highly increased. Storing water capacity has been demolished by war and supply chains have been occupied by military personnel, which makes the delivery of water far more difficult. In 2015, over 15 million people need healthcare and over 20 million need clean water and sanitation—an increase of 52 percent since the intervention, but the government agencies can not afford to deliver clean water to displaced Yemeni citizens.[417]

Agriculture

[edit]The Yemen civil war resulted in a severe lack of food and vegetation. Agricultural production in the country has suffered substantially leaving Yemen to face the threat of famine. Yemen has been since UNSC resolution 2216 was approved in April 2015,[378] under blockade by land, sea, and air which has disrupted the delivery of many foreign resources to Houthi-controlled territory. In a country where 90% of the food requirements are met through imports, this blockade has had serious consequences concerning the availability of food to its citizens.[418] It is reported that out of the population of 24 million in Yemen, everyday 13 million are going hungry and 6 million are at risk of starvation.[418] In October 2016, Robert Fisk reported that there is strong evidence suggesting that the agricultural sector in Houthi-controlled territory was being deliberately destroyed by the Saudi-led coalition, thus exacerbating the food shortage and leaving the Houthis dependent solely on imports, which are difficult to obtain in view of the blockade.[419]

See also

[edit]- Outline of the Yemeni crisis, revolution, and civil war (2011–present)

- Casualty recording

- Airstrikes on Yemen

- Houthi–Saudi Arabian conflict

- Al-Qaeda insurgency in Yemen

- United Arab Emirates takeover of Socotra

- Burkan-1

- Burkan-2

- Iraqi insurgency (2011–2013)

- War in Iraq (2013–2017)

- Second Libyan Civil War

- Syrian civil war

- Spillover of the Syrian civil war

- List of aviation shootdowns and accidents during the Saudi Arabian–led intervention in Yemen

- Muna Luqman

- Red Sea crisis

- Operation Prosperity Guardian

Notes

[edit]- ^ Since April 2022, the Southern Transitional Council is part of the Yemeni government led by the Presidential Leadership Council. Multiple sources:

- Salem, Mostafa; Kolirin, Lianne (7 April 2022). "Hopes of peace in Yemen as President hands power to new presidential council". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- Ghobari, Mohamed (7 April 2022). "Yemen president sacks deputy, delegates presidential powers to council". Reuters. Aden. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Al-Sakani, Ali (19 April 2022). "Yemen inaugurates new presidential council". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023.

- ^ logistic support and assistance with the naval blockade of Houthi-held territories in October 2016[42][43][44]

- ^ training, intelligence, logistical support, weapons, and blockade up to 2017[46][47][48][49]

- ^ sources:

- Juneau, Thomas (1 May 2016). "Iran's policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: A limited return on a modest investment". International Affairs. 92 (3): 647–663. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12599.

- Jones, Seth G.; Thompson, Jared; Ngo, Danielle; Bermudez, Joseph S. Jr.; McSorley, Brian (21 December 2021). "The Iranian and Houthi War against Saudi Arabia". Center for Strategic & International Studies. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023.

- Aldemagni, Eleonora (22 March 2023). "Houthis and Iran: A War Time Alliance". Italian Institute for International Political Studies. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023.

- ^ Sources:

- Nissenbaum, Dion; Said, Summer; Falcon, Benoit (16 March 2023). "Iran Agrees to Stop Arming Houthis in Yemen as Part of Pact With Saudi Arabia". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

- Gallagher, Adam; Hamasaeed, Sarhang; Nada, Garrett (16 March 2023). "What You Need to Know About China's Saudi-Iran Deal". United States Institute of Peace. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023.

- "Iran to halt weapon supplies to Houthis as part of deal with Saudi Arabia: Report". Al-Arabiya. 16 March 2023. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023.

- "Iran agrees to stop arming Houthis in Yemen as part of deal with Saudi Arabia – Wall Street Journal report". Arab News. 16 March 2023. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023.

- ^ Sources:

- "UN Security Council condemns Houthi attacks on Saudi Arabia". Al-Arabiya News. 4 April 2022. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022.

- "The International Community Timidly Condemns the Houthis Attack". South24 Center for News and Studies. 22 October 2022. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022.

- "Security Council Press Statement on Yemen". OCHA. 26 October 2022. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022.

- ^ Sources:

- "Security Council Renews Arms Embargo, Travel Ban, Asset Freeze Imposed on Those Threatening Peace in Yemen, by 11 Votes in Favour, None against, 4 abstentions". United Nations: Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023.

- Nichols, Michelle (1 March 2022). "U.N. arms embargo imposed on Yemen's Houthis amid vote questions". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023.

- "UN votes unanimously to extend sanctions on Yemen's Houthis". The Associated Press. 16 February 2023. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023.

- ^ sources:

- Juneau, Thomas (1 May 2016). "Iran's policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: A limited return on a modest investment". International Affairs. 92 (3): 647–663. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12599.

- Jones, Seth G.; Thompson, Jared; Ngo, Danielle; Bermudez, Joseph S. Jr.; McSorley, Brian (21 December 2021). "The Iranian and Houthi War against Saudi Arabia". Center for Strategic & International Studies. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023.

- Aldemagni, Eleonora (22 March 2023). "Houthis and Iran: A War Time Alliance". Italian Institute for International Political Studies. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023.

- ^ Sources:

- Nissenbaum, Dion; Said, Summer; Falcon, Benoit (16 March 2023). "Iran Agrees to Stop Arming Houthis in Yemen as Part of Pact With Saudi Arabia". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

- Gallagher, Adam; Hamasaeed, Sarhang; Nada, Garrett (16 March 2023). "What You Need to Know About China's Saudi-Iran Deal". United States Institute of Peace. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023.

- "Iran to halt weapon supplies to Houthis as part of deal with Saudi Arabia: Report". Al-Arabiya. 16 March 2023. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023.

- "Iran agrees to stop arming Houthis in Yemen as part of deal with Saudi Arabia – Wall Street Journal report". Arab News. 16 March 2023. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023.

References

[edit]- ^ Eleonora Ardemagni (19 March 2018). "Yemen's Military: From the Tribal Army to the Warlords". IPSI. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ "Death of a leader: Where next for Yemen's GPC after murder of Saleh?". Middle East Eye. 23 January 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ See:

- "Exclusive: Iran Steps up Support for Houthis in Yemen's War – Sources". U.S. News & World Report. 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Arab coalition intercepts Houthi ballistic missile targeting Saudi city of Jazan". english.alarabiya.net. Al Arabiya. 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Taleblu, Behnam Ben; Toumaj, Amir (21 August 2016). "Analysis: IRGC implicated in arming Yemeni Houthis with rockets". www.longwarjournal.org. Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Segall, Michael (2 March 2017). "Yemen Has Become Iran's Testing Ground for New Weapons". jcpa.org. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Exclusive: Iran steps up weapons supply to Yemen's Houthis via Oman – officials". Reuters. 20 October 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017.

- "US involvement in the Yemen war just got deeper | Public Radio International". Pri.org. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

Kube, Courtney (27 October 2016). "U.S. Officials: Iran Supplying Weapons to Yemen's Houthi Rebels". NBC News. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017. - Wright, Galen (1 October 2015). "Saudi-led Coalition seizes Iranian arms en route to Yemen". armamentresearch.com. Armament Research Services. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ O Falk, Thomas (8 March 2022). "The limits of Iran's influence on Yemen's Houthi rebels". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022.

Iran has said it supports the Houthis politically, but denies sending the group weapons. ... While the US and others have accused Iran of supplying the Houthis with rocket and drone technology that has allowed them to attack far beyond Yemen's borders, it is unclear whether that is 100 percent accurate..

- ^ See:

- Al-Abyad, Said (11 March 2017). "Yemeni Officer: 4 Lebanese 'Hezbollah' Members Caught in Ma'rib". english.aawsat.com. Asharq Al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Pestano, Andrew V. (25 February 2016). "Yemen accuses Hezbollah of supporting Houthi attacks in Saudi Arabia". www.upi.com. Sanaa, Yemen: United Press International. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.