Ghetto riots (1964–1969)

| Ghetto riots | |

|---|---|

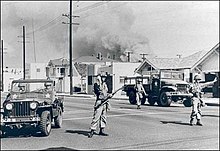

A Black man arrested by white LAPD officers during the Watts uprising | |

| Date | 16 July 1964 – 29 July 1969 |

| Location | |

| Caused by | |

| Methods | Widespread rioting, looting, assault, arson, property damage |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 200+ |

| Arrested | 20,000+ |

The term ghetto riots, also termed ghetto rebellions, race riots, or negro riots refers to a period of widespread urban unrest and riots across the United States in the mid-to-late 1960s, largely fueled by racial tensions and frustrations with ongoing discrimination, even after the passage of major Civil Rights legislation; highlighting the issues of racial inequality in Northern cities that were often overlooked in the earlier focus on the Southern states.[1][2]

The six days of unrest during the Harlem riot of 1964 is viewed as the first of clusters of riots, uncoordinated with each other, evidently unplanned, most often in cities during the summer months. The pattern caused over 150 separate incidents of violence and unrest over the "long, hot summer of 1967" (the most destructive riots taking place in Detroit and Newark), came to a climax during the national wave of King assassination riots in over 100 American cities in 1968, and relented in 1969.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]Before the ghetto riots of the 1960s, African American violent resistance to challenge white dominance was much more limited, including only small slave rebellions and armed defenses in the early 1900s. Most of these actions were defensive in nature rather than retaliatory, it was not until the Harlem riots of 1935 and 1943 that African Americans seemed to take initiative in violent conflicts. By the 1950s and 1960s, significant societal changes had taken place which fostered conditions for much more open rebellion.[2] Recent urban decay caused by white flight and middle-class Black flight from city centers also antagonized lower-class minority populations who had struggled to migrate to cities.[3]

Cause of riots

[edit]Deep-rooted racial discrimination in housing, employment, education, and the legal system created a cycle of poverty and limited opportunities for African Americans. Segregation practices forced Black residents into dilapidated and overcrowded urban neighborhoods with inadequate infrastructure. Frequent incidents of excessive force by police officers against Black citizens, often seen as unpunished, fueled anger and resentment. High unemployment rates among Black communities, coupled with low wages and limited job prospects, led to widespread economic hardship. The shift from manufacturing jobs to service-based economies in the latter half of the 20th century caused major job losses in industrial cities, leaving many urban residents unemployed. White residents leaving urban areas for suburban communities with better schools and housing, taking wealth and tax revenue with them, further exacerbating urban issues. While significant civil rights legislation had been passed, many African Americans felt that the pace of change was too slow and the progress was not reflected in their daily lives.[4][5][6][7][8]

Immediate causes were often aggressive confrontations between African Americans and whites or police officers that drew a crowd and began to spiral into violence and chaos.[6]

Riots

[edit]The Harlem riot in 1964 is seen as the beginning of a wave of civil unrest that would engulf New York City and begin to be seen in cities throughout the country until calming in 1968 with the last being the King assassination riots. These urban riots were unplanned and mostly attacked property of white owned businesses rather than people. Before this, most American riots involved brutal attacks against minorities. The riots shifted perceptions of the Civil Rights Movement from a primarily nonviolent struggle for equality to a recognition of the potential for violent uprisings as a response to oppression. Many Americans viewed the riots with fear and concern, which led to debates about law enforcement practices and social policies. This change influenced both public opinion and political action, prompting some leaders within the Civil Rights Movement to reconsider their strategies and approaches to advocating for justice.[9][10] The unrest resulted in over 150 deaths and over 20,000 arrests.[3][11]

1965: Watts

[edit]

The momentum for the advancement of civil rights came to a sudden halt in August 1965 with riots in the Watts district of Los Angeles. The riots were ignited by the arrest of Marquette Frye during a traffic stop, which escalated into a physical confrontation with police officers and drew a large crowd of onlookers. During the six days of unrest, rioters engaged in widespread looting of stores, burning buildings through arson, and in some cases, using sniper tactics to fire at authorities. To quell the violence, National Guard troops were deployed to the area, imposing a curfew.[12][13] Sergeant Ben Dunn of the LAPD recalled, "The streets of Watts resembled an all-out war zone in some far-off foreign country; it bore no resemblance to the United States of America."[14]

After 34 people were killed and $35 million (equivalent to $338.39 million in 2023) in property was damaged, the public feared an expansion of the violence to other cities, and so the appetite for additional programs in President Lyndon Johnson's agenda was lost.[15][16]

1967: Newark and Detroit

[edit]

In what is known as the "Long hot summer of 1967," more than 150 riots erupted across the United States, with the most significant occurring in Detroit, Michigan and Newark, New Jersey.[17][18]

The Newark riots were sparked by the arrest and beating of John William Smith, a Black cab driver, by police officers. The unrest lasted for five days, involving widespread looting, arson, and violent confrontations with police and National Guard troops. Some 26 people were killed, more than 700 were injured, and more than 1,000 residents were arrested.[19][20] $10 million (equivalent to $91.38 million in 2023) in property was damaged, and destroyed multiple plots, several of which are still covered in decay as of 2017.[21] The Boston Globe described the Newark riots as "a revolution of black Americans against white Americans, a violent petition for the redress of long-standing grievances." The Globe asserted that Great Society legislation had affected little fundamental improvement.[19]

In Detroit, a large black middle class had begun to develop among those African Americans who worked at unionized jobs in the automotive industry. These workers complained of persisting racist practices, limiting the jobs they could have and opportunities for promotion. The United Auto Workers channeled these complaints into bureaucratic and ineffective grievance procedures.[22] Violent white mobs enforced the segregation of housing up through the 1960s.[23] The Detroit riots were sparked by a police raid on an unlicensed after-hours bar, commonly called the "Blind Pig," in a predominantly Black neighborhood. The riots lasted for five days, causing significant property damage, 1,200 injuries, and at least 43 deaths (33 of those killed were Black residents of the city).[24] Governor George Romney sent in 7,400 National Guard troops to quell fire bombings, looting, and attacks on businesses and police. President Lyndon Johnson deployed U.S. Army troops with tanks and machine guns.[25] Residents reported that police officers and National Guardsmen shot at black civilians and suspects indiscriminately.[23][26][25]

At an August 2, 1967 cabinet meeting, Attorney General Ramsey Clark warned that untrained and undisciplined local police forces and National Guardsmen might trigger a "guerrilla war in the streets," as evidenced by the climate of sniper fire in Newark and Detroit.[27][28][29][30] Snipers were a significant element in many of the riots, creating a dangerous situation for both law enforcement and civilians, with shooters often targeting from rooftops and other concealed locations.[31][32]

1968: Riots following assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

[edit]

The April 4, 1968, assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. sparked another wave of violent protests in more than 130 cities across the country.[33] Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Chicago experienced the worst riots. Some 21,000 federal troops and 34,000 National Guardsmen were called out in an attempt to restore order following $45 million (equivalent to $394.28 million in 2023) of property damage across the country. On Chicago's West Side three dozen major fires burned out of control, looting was rampant, and snipers sent fearful neighbors scurrying. By April 7, some 500 Chicagoans had been injured and 11 killed.[34][35][36]

A few days later, in a candid comment made to press secretary George Christian concerning the endemic social unrest in the nation's cities, President Johnson remarked, "What did you expect? I don't know why we're so surprised. When you put your foot on a man's neck and hold him down for three hundred years, and then you let him up, what's he going to do? He's going to knock your block off."[37] Congress, meanwhile, passed the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, which increased funding for law enforcement agencies and authorized wiretapping in certain situations. Johnson considered vetoing the bill, but the apparent popularity of the bill convinced him to sign it.[38] In August 1969, federal officials considered the period of large-scale riots to be over.[39]

Kerner Commission

[edit]The riots confounded many civil rights activists of both races due to the recent passage of major civil rights legislation. They also caused a backlash among Northern whites, many of whom stopped supporting civil rights causes.[40] President Johnson formed the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, informally known as the Kerner Commission, on July 28, 1967 to explore the causes behind the recurring outbreaks of urban civil disorder.[41][42] The commission's scope included the 164 disorders occurring in the first nine months of 1967. The president had directed them, in simple words, to document: "What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?"[43]

The commission's 1968 report identified police practices, unemployment and underemployment, and lack of adequate housing as the most significant grievances motivating the rage.[44] It suggested legislative measures to promote racial integration and alleviate poverty and concluded that the nation was "moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal."[45] The president, fixated on the Vietnam War and keenly aware of budgetary constraints, barely acknowledged the report.[46]

Reactions

[edit]The FBI blamed the misery of ghetto life, oppressive summer weather, and Communist agitation. President Lyndon B. Johnson was convinced that inner-city poverty and despair were the principal ingredients behind the summer upheavals.[19] Johnson publicly denounced the violence and looting occurring during the riots, calling on citizens to reject lawlessness and work towards peaceful solutions.[47]

Conservative elements of American society regarded the riots as evidence for the need of law and order. Richard Nixon made social order a prime issue in his 1968 campaign for president.[48]

The mayor of Jersey City (Thomas J. Whelan) instead saw the riots as an indicator that more social programs were needed for the city and in 1964 asked for federal funds to provide "new recreational, housing, educational and sanitary facilities for low‐income groups".[49]

Federal grants for "urban renewal and antipoverty efforts", as in New Haven, were also discussed in relation to the riots.[50] In August 1968, over $4 million were offered by the Justice Department to the states in what was described as "the first Federal money designated to prepare for and help avert rioting in the cities".[51] In April 1969, John Lindsay asked to increase federal funds[52] but as of November 1969 the $200 million promised to restore 20 cities had not yet come to fruition.[53]

Dynamics of riots

[edit]Rioters often acted collectively, destroying property they viewed as being owned by those exploiting them. Police officers often were antagonists to rioters and their actions and racist language became symbols of the oppressive conditions faced by African Americans.[6]

See also

[edit]- African-American history

- Civil rights movement

- King assassination riots

- List of ethnic riots#United States

- List of expulsions of African Americans

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Lynching in the United States

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Nadir of American race relations

- Post–civil rights era in African-American history

- Racism against African Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Red Summer

- United States racial unrest (2020–2023)

References

[edit]- ^ Louis C Goldberg (1968). "Ghetto Riots and Others: the Faces of Civil Disorder in 1967". Journal of Peace Research. 5 (2): 116–131. doi:10.1177/002234336800500202. S2CID 144309056.

- ^ a b David Boesel (1970). "The Liberal Society, Black Youths, and the Ghetto Riots". Psychiatry. 33 (2): 265–281. doi:10.1080/00332747.1970.11023628. PMID 5443881.

- ^ a b Joseph Boskin (1969). "The Revolt of the Urban Ghettos, 1964-1967". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 382: 1–14. doi:10.1177/000271626938200102. JSTOR 1037109. S2CID 145786180.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (2021). Justice Rising: Robert KennedyÕs America in Black and White. Harvard University Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-674-73745-7.

The summer of 1967—the "summer of love" for America's youth counterculture—was a "long hot summer" for Black urban Americans, a season of the deadliest and most widespread racial strife in US history. Racial clashes, disorders, and rebellions erupted in an estimated 164 cities in thirty-four states, bringing the nation's crisis to a boil.

- ^ "The Riots of the Long, Hot Summer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c Herbert J Gans (1968). "The Ghetto Rebellions and Urban Class Conflict". Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science. 29 (1): 42–51. doi:10.2307/3700905. JSTOR 3700905.

- ^ "Civil Rights & Race Riots in the 1960s | History & Examples". Study.com. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ Howard, Ashley M. (November 12, 2014). "How U.S. Urban Unrest in the 1960s Can Help Make Sense of Ferguson, Missouri, and Other Recent Protests". Scholars Strategy Network. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ "What the 1960s can teach us about modern-day protests". PBS. Retrieved December 15, 2024.

- ^ "CFP: Urban Rebellions in the 1960s". AAIHS. Retrieved December 15, 2024.

- ^ Janine Lang (May 2019). "Riot" Heritage of the Civil Rights Era (MS thesis). Columbia University. doi:10.7916/d8-sjrt-2987.

- ^ "Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles)". The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Oberschall, Anthony (1968). "The Los Angeles Riot of August 1965". Social Problems. 15 (3): 322–341. doi:10.2307/799788. JSTOR 799788.

- ^ Troy, Tevi (2016). Shall We Wake the President?: Two Centuries of Disaster Management from the Oval Office. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 156. ISBN 9781493024650.

- ^ Dallek, Robert (1998). Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961–1973. Oxford University Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-0-19-505465-1.

- ^ "Lyndon B. Johnson: The American Franchise". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. October 4, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ Evans, Farrell (October 6, 2023). "The 1967 Riots: When Outrage Over Racial Injustice Boiled Over". History.com. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ Upchurch, T. Adams (2007). Race Relations in the United States, 1960–1980. p. 35.

- ^ a b c Dallek (1998), p. 412.

- ^ Evans, Farrell (October 6, 2023). "The 1967 Riots: When Outrage Over Racial Injustice Boiled Over". History.com. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ Rojas, Rick; Atkinson, Khorri (July 11, 2017). "Five Days of Unrest That Shaped, and Haunted, Newark". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ Miller, Karen (October 1, 1999). "Review of Georgakas, Dan; Surkin, Marvin, Detroit, I Do Mind Dying: A Study in Urban Revolution".

- ^ a b "American Experience. Eyes on the Prize. Profiles". PBS. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Riots of the Long, Hot Summer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ a b McLaughlin 2014, pp. 1–9, 40–41.

- ^ Hubert G. Locke, The Detroit Riot of 1967 (Wayne State University Press, 1969).

- ^ Hinton, Elizabeth (2016). From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Harvard University Press. p. 108.

- ^ Flamm, Michael W. (2017). In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on Crime. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 276.

- ^ Bigart, Homer (July 16, 1967). "Newark Riot Deaths at 21 As Negro Sniping Widens; Hughes May Seek U.S. Aid". The New York Times.

- ^ Roberts, Gene (July 26, 1967). "Troops Battle Detroit Snipers, Firing Machine Guns From Tanks; Lindsay Appeals To East Harlem; Detroit Toll Is 31 Rioters Rout Police-- Guardsmen Released To Aid Other Cities". The New York Times.

- ^ LIFE Magazine, July 28, 1967

- ^ LIFE Magazine, August 4, 1967

- ^ Walsh, Michael. "Streets of Fire: Governor Spiro Agnew and the Baltimore City Riots, April 1968". Teaching American History in Maryland. Annapolis, Maryland: Maryland State Archives. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ "West Madison Street 1968". Associated Press. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "There's a Riot Goin' On: Riots in U.S. History (Part Two)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 15, 2024.

- ^ Stein, R. Conrad (1998). The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. p. 18.

- ^ Kotz, Nick (2005). Judgment days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the laws that changed America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 418. ISBN 0-618-08825-3.

- ^ Patterson (1996), p. 651.

- ^ Herbers, John (August 24, 1969). "U.S. Officials Say Big Riots Are Over – Large-City Negro Leaders Now Oppose Violence, but Racial Tensions Remain". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

Federal officials believe that the era of large-scale urban rioting of the kind seen in Los Angeles, Detroit and Newark in recent years has come to a close.

- ^ Mackenzie and Weisbrot (2008), pp. 337–338

- ^ Mackenzie and Weisbrot (2008), p. 335

- ^ Toonari. "Kerner Report". Africana Online. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Johnson, Lyndon B. (July 29, 1967). Woolley, John T.; Peters, Gerhard (eds.). "Remarks Upon Signing Order Establishing the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders". The American Presidency Project. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California.

- ^ Alice George. "The 1968 Kerner Commission Got It Right, But Nobody Listened".

- ^ ""Our Nation Is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal": Excerpts from the Kerner Report". History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web. Source: United States. Kerner Commission, Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968). American Social History Productions. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ McLaughlin, Malcolm (2014). The Long, Hot Summer of 1967: Urban Rebellion in America. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–9, 40–41. ISBN 978-1-137-26963-8.

- ^ "July 27, 1967: Speech to the Nation on Civil Disorders". Miller Center. October 20, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Clay Risen (April 4, 2008). "The legacy of the 1968 riots". TheGuardian.com.

- ^ "Jersey City Mayor Calls for U.s. Funds". The New York Times. August 10, 1964. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "New Haven Riots Hit 'Model City' – Grant for Urban Renewal Is Largest per Capita in U.S." The New York Times. August 21, 1967. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Offers States $4.35-Million To Help Avert Rioting in Cities". The New York Times. August 14, 1968. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ Carroll, Maurice (April 11, 1969). "Lindsay Presses U.S. on Riot Repairs". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

Mayor Lindsay prodded the Nixon Administration yesterday to come up with "far more" than the millions of dollars promised earlier this week to repair riot-wrecked neighborhoods.

- ^ Herbers, John (November 18, 1969). "Cities Lag in Riot Clean-Up Despite U.S. Aid Program". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

Seven months after President Nixon announced that $200million had been earmarked for a special effort to begin cleaning and refurbishing riot-damaged areas in 20 cities, the target areas appear pretty much as they were then -- firescarred, boarded up buildings and rubble-strewn lots and streets.