Sodium oxybate

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Xyrem, Lumryz, others[1] |

| Other names | NSC-84223, WY-3478 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605032 |

| License data | |

| Addiction liability | High[2][3] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous[4] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 88%[3] |

| Protein binding | <1%[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 0.5 to 1 hour. |

| Excretion | Almost entirely by biotransformation to carbon dioxide, which is then eliminated by expiration |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.231 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C4H7NaO3 |

| Molar mass | 126.087 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Sodium oxybate, sold under the brand name Xyrem among others, is a medication used to treat symptoms of narcolepsy: sudden muscle weakness and excessive daytime sleepiness.[3][7][8] It is used sometimes in France and Italy as an anesthetic given intravenously.[9]: 15, 27–28 It is also approved and used in Italy and in Austria to treat alcohol dependence and alcohol withdrawal syndrome.[10]

Sodium oxybate is the sodium salt of γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB). The clinical trials for narcolepsy were conducted just as abuse of GHB as a club drug and date rape drug became a matter of public concern. In 2000, GHB was made a Schedule I controlled substance in the United States, while sodium oxybate, when used under an FDA New Drug Application or Investigative New Drug application, was classified as a Schedule III controlled substance for medicinal use under the Controlled Substances Act, with illicit use subject to Schedule I penalties.[11]

Sodium oxybate was approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat symptoms of narcolepsy in 2002,[3] with a strict risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program mandated by the FDA.[3] The US label for sodium oxybate also has a black box warning because it is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant and may cause respiratory depression, seizures, coma, or death, especially if used in combination with other CNS depressants such as alcohol, and its use may cause dependence.[3] In Canada and the European Union it was classified as a Schedule III and a Schedule IV controlled substance, respectively.[12]

It was approved for treating symptoms of narcolepsy in the European Union in 2005.[7]

Orphan Medical had developed it and was acquired by Jazz Pharmaceuticals in 2005. The drug is marketed in Europe by UCB. Jazz Pharmaceuticals raised the price of the drug dramatically after it acquired Orphan,[13] and paid a $20M fine for off-label marketing of the drug in 2007.[14]

Medical uses

[edit]Clinical use of sodium oxybate was introduced in Europe in 1964 as an anesthetic given intravenously, but it was not widely used since it sometimes caused seizures. As of 2006, it was still authorized for this use in France and Italy but not widely used.[9]: 15, 27–28

The major use of sodium oxybate is in treating two of the symptoms of narcolepsy – cataplexy (sudden muscle weakness) and excessive daytime sleepiness.[3] Reviews of sodium oxybate concluded that it is well tolerated and associated with "significant reductions in cataplexy and daytime sleepiness",[15] and that its effectiveness "in treating major, clinically relevant narcolepsy symptoms and sleep architecture abnormalities" has been established.[16] However, because of the risks of abuse associated with this medication, it is available in the US only through a REMS program mandated by the FDA. The program requires that providers who prescribe it are certified to do so, that it is dispensed only from a central pharmacy that is certified to do so, and that people to whom it is prescribed must be enrolled in a program for the drug and must document that they are using the drug safely.[3]

Investigations of its use in dealing with alcohol withdrawal syndrome and in the maintenance of abstinence began in 1989 in Italy, where it was then approved in these indications in 1991. It has also been approved for use in Austria.[17] Over the years, several studies were conducted to further substantiate sodium oxybate efficacy in these indications. Results of small studies suggest it may be "better than naltrexone and disulfiram regarding abstinence maintenance and prevention of craving in the medium term, i.e. 3–12 months."[18] In a 2014 review, Gillian Keating described sodium oxybate as a "useful option for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and for the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol dependence."[17] However, a 2018 review recognised the evidence for its efficacy but noted safety concerns and concluded that "studies are still limited and investigations including a larger number of patients are needed."[19]

In this context, a study published in 2019 analyzed safety data from 40 clinical trials and from a pharmacovigilance database covering around 260,000 alcohol-dependent patients treated with sodium oxybate in Italy and Austria.[20] Results showed that sodium oxybate was well-tolerated, risks were controlled, and no safety concerns were reported.[20] The approved sodium oxybate dose regimen for the treatment of alcohol dependence (i.e., around 3.2 g/day) is lower than the one for the treatment of narcolepsy (4.5–9 g/night).[20] In 2023, a PhD thesis conducted at the University of Amsterdam, presented the results of large clinical trials, including a phase 3 trial, and of meta-analyses that confirmed the efficacy, good tolerance, and safety of sodium oxybate in the maintenance of abstinence, particularly in severe alcohol-dependent patients.[21] A group of international researchers has also considered in 2018 that "sodium oxybate has an excellent risk benefit ratio for this indication" and that it is "a very promising therapeutic option for the most severe alcohol-dependent patients and may provide substantial clinical and public health benefit and costs".[22]

Multiple trials have shown sodium oxybate to be effective in treating important symptoms of fibromyalgia, such as pain and poor sleep structure.[23] However, in 2010, the FDA voted unanimously against this indication, with commenters citing its potential for abuse as a street drug.

Pregnant women should not take it, and women should not become pregnant while taking it. It is excreted in breast milk and should not be used by mothers who are breast feeding.[7]

Adverse effects

[edit]The US label for sodium oxybate has a black box warning because it is a central nervous system depressant (CNS depressant) and for its potential for abuse. Other potential adverse side effects include respiratory depression, seizures, coma, and death, especially when it is taken in combination with other CNS depressants such as alcohol.[3][24][25] Cases of severe dependence and cravings have been reported with excessive and illicit use of this medication.[3][24][26] GHB, the protonated (acidic) form of this salt, has been used to commit drug-facilitated sexual assault and date rape,[24][25][27][28] though the illicit form of GHB typically has different characteristics from pharmaceutical-grade sodium oxybate.[29]

Sodium oxybate causes dizziness, nausea, and headache in 10% to 20% of people who take it; nausea is more common in women than men.[7][30] Between 1% and 10% of people experience nasal congestion, runny nose, or sore throat, loss of appetite, distorted sense of taste, cataplexy, weakness, nervousness or anxiety, depressed mood, nightmares or abnormal dreams, sleep paralysis, sleepwalking, or other sleep disturbances including insomnia, sleepiness or sedation, falls, vertigo, tremor, balance disorder, cognitive issues including disturbance in attention, confusion or disorientation, numbed sense of touch, tingling, blurred vision, heart palpitations, high blood pressure, shortness of breath, snoring, vomiting, diarrhea, stomach pain, excessive sweating, rashes, joint pain, muscle pain, back pain, muscle spasms, bedwetting, urinary incontinence, and swelling of the limbs.[7]

Overdose

[edit]Reports of overdose in medical literature are generally from abuse, and often involve other drugs as well. Symptoms include vomiting, excessive sweating, periods of stopped breathing, seizures, agitation, loss of psychomotor skills, and coma. Overdose can lead to death due to respiratory depression. People who overdose may die from asphyxiation resulting from choking on vomit and/or aspiration. People that have overdosed or suspected of overdosing may need to be made to vomit, be intubated, or/and put on a ventilator.[3][7]

Interactions

[edit]Sodium oxybate should not be used with other drugs that are CNS depressants like alcohol or sedatives.[3] Use with divalproex results in about a 25% increase in the availability of sodium oxybate.[3]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]The full mechanism of action of sodium oxybate is poorly understood.[3][7] GHB is a normal metabolite of GABA that interacts with the GABAB receptor and the GHB receptor.[3] It has been shown to enhance the restorativeness of sleep in part by altering sleep architecture in narcoleptic patients.[31]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Sodium oxybate is rapidly absorbed with high bioavailability, however due to a very high rate of first-pass metabolism the effective bioavailability is only about 25%.[32] Less than 1% is bound to plasma protein. The average time to peak plasma concentration ranges from 0.5 to 1.25 hours.[32] It has a very short half-life of between 20 - 40 minutes. A high-fat meal may increase the half-life to 60 minutes.[32] Because of its short half-life some patients take the drug twice nightly.[32]

Only a minor portion (1–5%) of the administered GHB dose is excreted unchanged in the urine. Instead, the vast majority (95–98%) undergoes extensive metabolism in the liver into carbon dioxide and water.[3][4] The primary route involves the conversion of GHB to succinic semialdehyde (SSA) by either GHB dehydrogenase or GHB transhydrogenase. SSA is further oxidized by succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) to succinic acid, which enters the Krebs cycle and is ultimately converted into carbon dioxide and water.[4][33][34][35] It does not inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes in the liver at therapeutic concentrations.[32]

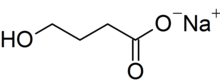

Chemistry

[edit]Sodium oxybate is the sodium salt of γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB). Its systematic chemical name is sodium 4-hydroxybutanoate, though synonyms like sodium γ-hydroxybutyrate are commonly used. Its condensed structural formula is HOCH

2CH

2CH

2CO

2Na (molecular formula: C

4H

7NaO

3) and its molar mass is 126.09 g mol−1. It is highly hydrophilic.[3] Treating the salt with acid allows the carboxylic acid form of the compound, which is GHB, to be recovered.

History

[edit]Alexander Zaytsev worked on this chemical family and published work on it in 1874.[36]: 79 [37] The first extended research into sodium oxybate and its use in humans was conducted in the early 1960s by Henri Laborit to study the neurotransmitter GABA.[9]: 11–12 [38] It was studied for a range of uses, including obstetric surgery, during childbirth, and as an anxiolytic; there were anecdotal reports of it having antidepressant and aphrodisiac effects as well.[9]: 27 It was also studied as an intravenous anesthetic agent and was marketed for that purpose starting in 1964 in Europe, but it was not widely adopted as it caused seizures; as of 2006, that use was still authorized in France and Italy but not widely used.[9]: 27–28 sodium oxybate was also studied to treat alcohol addiction[9]: 28–29 and for use in narcolepsy from the 1960s onwards.[9]: 28

In May 1990, GHB was introduced as a dietary supplement and was marketed to bodybuilders for help with weight control, as a sleep aid, and as a "replacement" for L-tryptophan, which was removed from the market in November 1989 when batches of it were found to cause eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. By November of that year, 57 cases of illness caused by the GHB supplements had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with people having taken up to three teaspoons of GHB; there were no deaths, but nine people needed care in an intensive care unit.[39][40] The FDA issued a warning in November 1990 that the sale of GHB was illegal.[39] GHB continued to be manufactured and sold illegally, and it and its analogs were adopted as a club drug and came to be used as a date rape drug. The DEA made seizures and the FDA reissued warnings several times throughout the 1990s.[41][42][43]

At the same time, research on the use of sodium oxybate had formalized, as a company called Orphan Medical Inc. had filed an Investigational New Drug application and was running clinical trials with the intention of gaining regulatory approval for use to treat narcolepsy.[9]: 18–25, 28 [44]: 10 In 1996, Orphan contracted with Lonza Group, a contract manufacturer for supply of the drug.[45]

In 2000, the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Prevention Act of 2000 was signed into law in the US, which put GHB on Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, but sodium oxybate, when used under an IND or NDA from the US FDA, was considered a Schedule III substance, but with Schedule I trafficking penalties.[46][47]

Sodium oxybate was approved by the FDA in 2002 under the brand name Xyrem with a strict risk control strategy to prevent drug diversion and control the risk of abuse by people to whom it was prescribed.[48]

Orphan Medical licensed the right to market the drug in Europe to Celltech in 2003.[49][50] In 2004, Celltech was acquired by UCB[51] and in 2005 Jazz Pharmaceuticals acquired Orphan Medical.[52]

In January 2007, Valeant announced that Jazz Pharmaceuticals had licensed the rights to market Xyrem in Canada to Valeant.[53] Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Valeant terminated the agreement in 2017.[54]

In July 2007, Jazz Pharmaceuticals and their subsidiary, Orphan Medical, pleaded guilty to a criminal charge of felony misbranding in their marketing of sodium oxybate; they also settled a civil suit at the same time. Jazz Pharmaceuticals paid $20 million in total and agreed to a corporate integrity agreement and to implement internal reforms.[14][55][56] The FDA sent Jazz Pharmaceuticals an FDA warning letter about safety violations in September 2007.[57]

In 2010, the FDA rejected Jazz Pharmaceuticals' New Drug Application for use of sodium oxybate in fibromyalgia.[58]

In October 2011, the FDA sent Jazz Pharmaceuticals another FDA warning letter for failing to collect, evaluate, and promptly report adverse effects to the FDA after it started marketing the drug.[57] It sent another letter in 2013 saying that the problems described in the 2011 letter appeared to be resolved.[59]

In January 2017, the FDA approved the first generic sodium oxybate product for narcolepsy symptoms, which is also subject to the same REMS program conditions as the original.[60] By April 2017, seven companies had filed Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) with the FDA to market generic versions of Xyrem, which resulted in Jazz Pharmaceuticals filing patent infringement cases against them. Hikma Pharmaceuticals had been the first company to file an ANDA and Jazz Pharmaceuticals settled with them in April 2017; under the agreement Hikma could begin selling an authorized generic in 2023 under Jazz Pharmaceuticals' REMS, and would have five years of exclusivity, however, those conditions could change if Jazz Pharmaceuticals' patents were invalidated.[61][62] In 2023, Jazz Pharmaceuticals licensed the right to produce an authorized generic of Xyrem to Hikma Pharmaceuticals, marketed as "Sodium Oxybate Oral Solution".[63]

In May 2023, the FDA approved Lumryz, an extended-release oral suspension of sodium oxybate.[6][64]

Society and culture

[edit]Regulation

[edit]In the United States, GHB is a Schedule I controlled substance, while sodium oxybate, when used under an FDA NDA or IND application, is classified as a Schedule III controlled substance for medicinal use under the Controlled Substances Act, with illicit use subject to Schedule I penalties.[11]

In Canada and the European Union, as of 2009, it is classified as a Schedule III and a Schedule IV controlled substance, respectively.[12]

Cost

[edit]In the US, the cost in Q3 2015 of Xyrem was $5,468.09 per 180 mL bottle at 500 mg/mL— a 10 to 15-day supply when prescribed at the typical 6–9 g per day. As of 2017 the cost of sodium oxybate in the UK was £540.00 to £1,080.00 for a thirty-day supply,[65] which at typical doses is £6,500 to £13,100 per year.[66]

Jazz Pharmaceuticals raised the price of Xyrem 841% earning a total of $569 million in 2013 and representing more than 50% of Jazz Pharmaceutical's revenues.[13] In 2007 it cost $2.04; by 2014 it cost $19.40 per 1-milliliter dose.[13] Jazz offers copay assistance to help patients access the expensive drug.[13] According to DRX, a drug-data report published by Bloomberg, Jazz Pharmaceuticals price increase on Xyrem topped the list of price hikes in 2014.[13]

Historically, orphan drugs cost more than other drugs and have received special treatment since the enactment of the US Orphan Drug Act of 1983. However, these steep price increases of orphan and other specialty drugs has come under scrutiny.[13] The average cost of a specialty drug in the US was $65,000 annually in June 2013 (about $5,416 a month). The price of Xyrem in the US has inflated by an average of 40% annually since it became available as a prescription.[67]

The first authorized generic sodium oxybate, produced by Hikma Pharmaceuticals, was made available in January 2023.[63]

In European Union countries, the government either provides national health insurance (as in the UK and Italy) or strictly regulates quasi-private social insurance funds (as in Germany, France, and the Netherlands). These government agencies are the sole purchaser (or regulator) of medical goods and services and have the power to set prices.[68] The cost of pharmaceuticals, including sodium oxybate, tends to be lower in these countries.[68]

NHS England authorises and pays for sodium oxybate by means of individual funding requests on the basis of exceptional circumstances. The British Department of Health pays for the medication for 80 patients who are taking legal action over problems linked to the use of the swine flu vaccine Pandemrix at a cost of £12,000 a year. As of 2016, there were many areas in the UK where NHS did not pay for sodium oxybate.[69][70] In May 2016 they were ordered by the High Court to provide funding to treat a teenager with severe narcolepsy. The judge criticised their "thoroughly bad decision" and "absurd" policy discriminating against the girl when hundreds of other NHS patients already receive the drug.[71]

Names

[edit]Sodium oxybate is the common name for the chemical; it has no international nonproprietary name (INN).[72]

As of April 2018, sodium oxybate is sold under the following brands: Alcover (Italy), Gamma-OH (France), Natrii oxybutyras Kalceks (Latvia), Somsanit (Germany), Xyrem (many countries by Jazz Pharmaceuticals and UCB).[1]

In 2023, the first authorized generic of Xyrem was made available in the US.[63]

Research

[edit]Jazz Pharmaceuticals has been developing JZP-386, a deuterated analog of sodium oxybate. The company presented Phase I results in 2015, stating that deuterium-related effects made it necessary to do further formulation work as part of the drug's development.[73]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "International brands for Sodium Oxybate -". Drugs.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Tay E, Lo WK, Murnion B (2022). "Current Insights on the Impact of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) Abuse". Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 13: 13–23. doi:10.2147/SAR.S315720. PMC 8843350. PMID 35173515.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Xyrem- sodium oxybate solution". DailyMed. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c Busardò FP, Jones AW (January 2015). "GHB pharmacology and toxicology: acute intoxication, concentrations in blood and urine in forensic cases and treatment of the withdrawal syndrome". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 47–70. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210215423. PMC 4462042. PMID 26074743.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "Lumryz- sodium oxybate for suspension, extended release". DailyMed. June 7, 2023. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "UK label Summary of Product Characteristics". Electronic Medicines Compendium. September 8, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "Xyrem (sodium oxybate) Information". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. January 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Critical review of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB)" (PDF). 2012.

- ^ "Alcover: Riassunto delle Caratteristiche del Prodotto". Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. March 31, 2017. Index page

- ^ a b "GHB Fact Sheet" (PDF). DEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Wang YG, Swick TJ, Carter LP, Thorpy MJ, Benowitz NL (August 2009). "Safety overview of postmarketing and clinical experience of sodium oxybate (Xyrem): abuse, misuse, dependence, and diversion". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 5 (4): 365–371. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27549. PMC 2725257. PMID 19968016.

- ^ a b c d e f Staton T (May 7, 2014). "10 big brands keep pumping out big bucks, with a little help from price hikes". Fierce Pharma. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ a b "Press release: US Attorney's Office - Eastern District of New York". US Department of Justice. July 13, 2007.

- ^ Alshaikh MK, Tricco AC, Tashkandi M, Mamdani M, Straus SE, BaHammam AS (August 2012). "Sodium oxybate for narcolepsy with cataplexy: systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 8 (4): 451–458. doi:10.5664/jcsm.2048. PMC 3407266. PMID 22893778.

- ^ Boscolo-Berto R, Viel G, Montagnese S, Raduazzo DI, Ferrara SD, Dauvilliers Y (October 2012). "Narcolepsy and effectiveness of gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 16 (5): 431–443. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2011.09.001. PMID 22055895.

- ^ a b Keating GM (January 2014). "Sodium oxybate: a review of its use in alcohol withdrawal syndrome and in the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol dependence". Clinical Drug Investigation. 34 (1): 63–80. doi:10.1007/s40261-013-0158-x. PMID 24307430. S2CID 2056246.

- ^ Busardò FP, Kyriakou C, Napoletano S, Marinelli E, Zaami S (December 2015). "Clinical applications of sodium oxybate (GHB): from narcolepsy to alcohol withdrawal syndrome" (PDF). European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 19 (23): 4654–4663. PMID 26698265.

- ^ Mannucci C, Pichini S, Spagnolo EV, Calapai F, Gangemi S, Navarra M, et al. (2018). "Sodium Oxybate Therapy for Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome and Keeping of Alcohol Abstinence". Current Drug Metabolism. 19 (13): 1056–1064. doi:10.2174/1389200219666171207122227. PMID 29219048. S2CID 2166038.

- ^ a b c Addolorato G, Lesch OM, Maremmani I, Walter H, Nava F, Raffaillac Q, et al. (February 2020). "Post-marketing and clinical safety experience with sodium oxybate for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and maintenance of abstinence in alcohol-dependent subjects". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 19 (2): 159–166. doi:10.1080/14740338.2020.1709821. PMID 31876433. S2CID 209482660.

- ^ van den Brink W, Goudriaan A (May 11, 2023). Sodium oxybate for the treatment of alcohol dependence. University of Amsterdam. hdl:11245.1/ad0b0a9e-e28c-432d-81a9-ccdf39b190f8. ISBN 9789464730739. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ van den Brink W, Addolorato G, Aubin HJ, Benyamina A, Caputo F, Dematteis M, et al. (July 2018). "Efficacy and safety of sodium oxybate in alcohol-dependent patients with a very high drinking risk level". Addiction Biology. 23 (4): 969–986. doi:10.1111/adb.12645. PMID 30043457. S2CID 51716274.

- ^ Swick T (2011). "Sodium Oxybate: A Potential New Pharmacological Option for the Treatment of Fibromyalgia Syndrome". Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 3 (4): 167–178. doi:10.1177/1759720X11411599. PMC 3382678. PMID 29219048.

- ^ a b c Miller RL (2002). "GHB". The Encyclopedia of Addictive Drugs. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 182–185. ISBN 9780313318078.

- ^ a b Abadinsky H (2010). "GHB and GBL". Drug Use and Abuse: A Comprehensive Introduction (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 197–198. ISBN 9780495809913.

- ^ Galloway GP, Frederick SL, Staggers FE, Gonzales M, Stalcup SA, Smith DE (January 1997). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate: an emerging drug of abuse that causes physical dependence". Addiction. 92 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb03640.x. PMID 9060200.

- ^ "FDA Approves 'Date-Rape' Drug to Treat Sleep Disorder". The Washington Post. July 18, 2002. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Wedin GP, Hornfeldt CS, Ylitalo LM (January 2006). "The clinical development of gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB)". Current Drug Safety. 1 (1): 99–106. doi:10.2174/157488606775252647. PMID 18690919.

- ^ Carter LP, Pardi D, Gorsline J, Griffiths RR (September 2009). "Illicit gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and pharmaceutical sodium oxybate (Xyrem): differences in characteristics and misuse". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 104 (1–2): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.012. PMC 2713368. PMID 19493637.

- ^ Wise MS, Arand DL, Auger RR, Brooks SN, Watson NF (December 2007). "Treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin". Sleep. 30 (12): 1712–1727. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.12.1712. PMC 2276130. PMID 18246981.

- ^ Mamelak M. "Sleep, Narcolepsy, and Sodium Oxybate". Current Neuropharmacology. 20 (2): 272–291. doi:10.2174/1570159X19666210407151227. PMC 9413790.

- ^ a b c d e Robinson DM, Keating GM (2007). "Sodium oxybate: a review of its use in the management of narcolepsy". CNS Drugs. 21 (4): 337–354. doi:10.2165/00023210-200721040-00007. PMID 17381187.

- ^ Felmlee MA, Morse BL, Morris ME (January 2021). "γ-Hydroxybutyric Acid: Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Toxicology". The AAPS Journal. 23 (1): 22. doi:10.1208/s12248-020-00543-z. PMC 8098080. PMID 33417072.

- ^ Taxon ES, Halbers LP, Parsons SM (May 2020). "Kinetics aspects of Gamma-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1868 (5): 140376. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140376. PMID 31981617.

- ^ Kamal RM, van Noorden MS, Franzek E, Dijkstra BA, Loonen AJ, De Jong CA (March 2016). "The Neurobiological Mechanisms of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate Dependence and Withdrawal and Their Clinical Relevance: A Review". Neuropsychobiology. 73 (2): 65–80. doi:10.1159/000443173. hdl:2066/158441. PMID 27003176.

- ^ Lewis DE (2012). "Section 4.4.3 Aleksandr Mikhailovich Zaitsev". Early Russian organic chemists and their legacy. Springer. ISBN 9783642282195.

- ^ Saytzeff A (1874). "Über die Reduction des Succinylchlorids". Liebigs Annalen der Chemie (in German). 171 (2): 258–290. doi:10.1002/jlac.18741710216.

- ^ Laborit H, Jouany JM, Gerard J, Fabiani F (October 1960). "[Generalities concerning the experimental study and clinical use of gamma hydroxybutyrate of Na]". Agressologie (in French). 1: 397–406. PMID 13758011.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (November 1990). "Multistate outbreak of poisonings associated with illicit use of gamma hydroxy butyrate". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 39 (47): 861–863. PMID 2122223.

- ^ Dyer JE (July 1991). "gamma-Hydroxybutyrate: a health-food product producing coma and seizurelike activity". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (4): 321–324. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(91)90050-T. PMID 2054002.

- ^ Institute of Medicine, National Research Council (US) Committee on the Framework for Evaluating the Safety of Dietary Supplements (2002). "Appendix D: Table of Food and Drug Administration Actions on Dietary Supplements". Proposed Framework for Evaluating the Safety of Dietary Supplements: For Comment. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ "GHB: A Club Drug To Watch" (PDF). Substance Abuse Treatment Advisory. 2 (1). November 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Mason PE, Kerns WP (July 2002). "Gamma hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) intoxication". Academic Emergency Medicine. 9 (7): 730–739. doi:10.1197/aemj.9.7.730. PMID 12093716.

- ^ "Transcript: FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting". FDA. June 6, 2001.

- ^ "Jazz Pharma (JAZZ) Announces that Lonza has Terminated Their Sodium Oxybate Supply Agreement". Street Insider. March 25, 2010.

- ^ "2000 - Addition of Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid to Schedule I". US Department of Justice via the Federal Register. March 13, 2000. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "William J. Clinton: Statement on Signing the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act of 2000". February 18, 2000.

- ^ "FDA Approves 'Date-Rape' Drug to Treat Sleep Disorder". Washington Post. July 18, 2002.

- ^ "Celltech acquires rights to Xyrem from Orphan Medical - Pharmaceutical". The Pharma Letter. November 3, 2003.

- ^ "Form S-1/A EX-10.41 Amended and Restated Xyrem License and Distribution Agreement". www.sec.gov. Jazz Pharmaceuticals vis SEC Edgar. March 27, 2007. Form S-1/A Index page

- ^ "Celltech sold to Belgian firm in £1.5bn deal". the Guardian. May 18, 2004.

- ^ "Jazz completes Orphan Medical buy - Pharmaceutical industry news". The Pharma Letter. July 4, 2005.

- ^ "Press release: Valeant Pharmaceuticals Signs Licensing Agreement for Canadian Rights to (C)Xyrem(R) (Sodium Oxybate) from Jazz Pharmaceuticals. - Free Online Library". Valeant via Business Wire. January 12, 2007. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "10-K For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017". Jazz via SEC Edgar. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Berenson A (July 22, 2006). "Indictment of Doctor Tests Drug Marketing Rules". The New York Times.

- ^ Berenson A (July 14, 2007). "Maker of Narcolepsy Drug Pleads Guilty in U.S. Case". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "FDA Warning Letter, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc 10/11/11". Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ "FDA Says No to Jazz Pharma Fibromyalgia Drug". The New York Times. Associated Press. October 12, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "2013 - Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.- Close Out Letter". FDA. August 2, 2013.

- ^ "Press release: FDA approves a generic of Xyrem with a REMS Program". FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. January 17, 2017.

- ^ "This Rival Might Swipe 20% Of Jazz's Sleep Business, But Stock Perks Up | Investor's Business Daily". Investor's Business Daily. April 6, 2017.

- ^ "8-K". www.sec.gov. Jazz via SEC Edgar. April 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Hikma launches authorized generic of Xyrem (sodium oxybate) in the US". Hikma. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ Brooks M. "FDA OKs Once-Nightly Sodium Oxybate for Narcolepsy". Medscape. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Narcolepsy with or without cataplexy in adults: pitolisant | Guidance and guidelines: Other Treatments". NICE. March 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Kane N (May 2017). "Sodium oxybate for the treatment of narcolepsy with cataplexy in adults" (PDF). NHS Regional Drug & Therapeutics Centre (Newcastle). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Rattner S (June 30, 2013). "An Orphan Jackpot". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Danzon PM (Spring 2000). "Making sense of drug prices" (PDF). Regulation. 23 (1): 56–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ "Narcolepsy". NHS Choices. May 29, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "DH funds private prescriptions for drug denied to NHS patients". Health Service Journal. July 20, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "Judge criticises NHS England for 'totally irrational' drug decision". Health Service Journal. May 4, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ "Sodium oxybate: CHMP Scientific Discussion" (PDF). EMA. August 9, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018. Linked from EMA index page for EMEA 000593 Archived June 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ de Biase S, Nilo A, Gigli GL, Valente M (August 2017). "Investigational therapies for the treatment of narcolepsy". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 26 (8): 953–963. doi:10.1080/13543784.2017.1356819. PMID 28726523. S2CID 25638377.