User:Nanib/Chinese

Chinese civilization is one of the world's oldest.[1][2] In antiquity, the civilization prospered along the banks of the Yellow River.[3] After this time, the Chinese civilization grew to become a hegemonic power over most of Eastern Asia, and greatly influenced the traditions of its neighbors. Before contact with European powers in the 19th century, Chinese civilization had influenced history and global civilization greatly in numerous fields, including literature, music, diplomacy, philosophy, visual and martial arts, cuisine, and through numerous inventions which have had profound impact on the modern world.

This article expounds on the history, traditional tenets of the culture and norms of the Chinese civilization, and touches on its recent experience with Western culture and Westernization.

History

[edit]Prehistory and the Huaxia

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (2012) |

The history of the Han Chinese ethnic group is closely tied to that of the Chinese civilization. Han Chinese trace their ancestry back to the Huaxia people, who lived along the Huang He or Yellow River in northern China.[4] The famous Chinese historian Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian places the reign of the Yellow Emperor, the legendary ancestor of the Han Chinese, at the beginning of Chinese history. Although study of this period of history is complicated by lack of historical records, discovery of archaeological sites have identified a succession of Neolithic cultures along the Yellow River. Along the central reaches of the Yellow River were the Jiahu culture (7000 BCE to 6600 BCE), Yangshao culture (5000 BCE to 3000 BCE) and Longshan culture (3000 BCE to 2000 BCE). Along the lower reaches of the river were the Qingliangang culture (5400 BCE to 4000 BCE), the Dawenkou culture (4300 BCE to 2500 BCE), the Longshan culture (2500 BCE to 2000 BCE), and the Yueshi culture.

Early history

[edit]The first dynasty to be described in Chinese historical records is the Xia Dynasty, a legendary period for which scant archaeological evidence exists. They were overthrown by peoples from the east, who founded the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE). The earliest archaeological examples of Chinese writing date back to this period, from characters inscribed on oracle bone divination, but the well-developed oracle characters hint at a much earlier origin of writing in China. The Shang were eventually overthrown by the people of Zhou, which had emerged as a state along the Yellow River in the 2nd millennium BC.

The Zhou Dynasty was the successor to the Shang. Sharing the language and culture of the Shang people, they extended their reach to encompass much of the area north of the Yangtze River. Through conquest and colonization, much of this area came under the influence of sinicization and the proto-Han Chinese culture extended south. However, the power of the Zhou kings fragmented, and many independent states emerged. This period is traditionally divided into two parts, the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. This period was an era of major cultural and philosophical development known as the Hundred Schools of Thought. Among the most important surviving philosophies from this era are the teachings of Confucianism and Taoism.

Imperial history

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (2012) |

The era of the Warring States came to an end with the unification of China by the Qin Dynasty after it conquered all other rival states. Its leader, Qin Shi Huang, declared himself the first emperor, using a newly created title, thus setting the precedent for the next two millennia. He established a new centralized and bureaucratic state to replace the old feudal system, creating many of the institutions of imperial China, and unified the country economically and culturally by decreeing a unified standard of weights, measures, currency, and writing.

However, the reign of the first imperial dynasty was to be short-lived. Due to the first emperor's autocratic rule, and his massive construction projects such as the Great Wall which fomented rebellion into the populace, the dynasty fell soon after his death. The Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) emerged from the succession struggle and succeeded in establishing a much longer lasting dynasty. It continued many of the institutions created by Qin Shi Huang but adopted a more moderate rule. Under the Han Dynasty, arts and culture flourished, while the dynasty expanded militarily in all directions. This period is considered one of the greatest periods of the history of China, and the large Han Chinese ethnic takes its name from this dynasty.

The Han dynasty significantly expanded the reach of Chinese civilization beyond the Yellow River basin area in Northern China to include Southern China.

The fall of the Han Dynasty was followed by an age of fragmentation and several centuries of disunity amid warfare by rival kingdoms. During this time, areas of northern China were overrun by various non-Chinese nomadic peoples which came to establish kingdoms of their own, the most successful of which was Northern Wei established by the Xianbei. Starting from this period, the native population of China proper began to be referred to as Hanren, or the "People of Han", to distinguish from the nomads from the steppe; "Han" refers to the old dynasty. Warfare and invasion led to one of the first great migrations in Han population history, as the population fled south to the Yangtze and beyond, shifting the Chinese demographic center south and speeding up Sinicization of the far south. At the same time, in the north, most of the nomads in northern China came to be Sinicized as they ruled over large Chinese populations and adopted elements of Chinese culture and Chinese administration. Of note, the Xianbei rulers of the Northern Wei ordered a policy of systematic Sinicization, adopting Han surnames, institutions, and culture.

The Sui (581–618) and Tang Dynasties (618–907) saw the continuation of the complete Sinicization of the south coast of what is now China proper, including what are now the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong. The Tang dynasty also conquered regions which correspond to modern Gansu province and Xinjiang province. The later part of the Tang Dynasty, as well as the Five Dynasties period that followed, saw continual warfare in north and central China; the relative stability of the south coast made it an attractive destination for refugees.

The next few centuries saw successive invasions of non-Han peoples from the north, such as the Khitans and Jurchens. In 1279 the Mongols (Yuan Dynasty) conquered all of China, becoming the first non-Chinese to do so. The Mongols divided society into four classes, with themselves occupying the top class and Han Chinese in the bottom two classes.

In 1368 Han Chinese rebels drove out the Mongols and, after some infighting, established the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Settlement of Han Chinese into peripheral regions continued during this period, with Yunnan in the southwest receiving a large number of migrants.

Qing Empire

[edit]Jurchen tribespeople called Manchus rebelled against the Ming dynasty in 1616 under chief Nurhaci and founded the Later Jin dynasty after managing to conquered much of Liaoning province by 1626. In 1644, Beijing was captured by a peasant rebel army lead by Li Zicheng, founder of the short-lived Shun dynasty. The Manchu's then allied with Ming Dynasty general Wu Sangui in union against Li Zicheng and seized control of Beijing, after which they claimed the Mandate of Heaven and declared the founding of the Qing dynasty.

After the eventual conquest of the Southern Ming dynasty by 1663. Remnant Ming forces led by Koxinga fled to Taiwan, where they eventually capitulated to Qing forces in 1683. After the suppression of a revolt by the Three Feudatories in Southern China, the Qing had full control of China. The Qing dynasty became heavily Sinicized after claiming the Mandate of Heaven, and adopted many Chinese mannerisms.

Expansion of Chinese territory

[edit]

Taiwan, previously inhabited mostly by non-Han aborigines, was Sinicized via large-scale migration accompanied with assimilation during this period, despite efforts by the Manchus to prevent this, as they found it difficult to maintain control over the island. At the same time the Manchus prohibited Han Chinese migration to sparsely- and Manchu-inhabited Manchuria, because the Manchus perceived it as the home base of their dynasty. In 1681, the emperor ordered construction of the Willow Palisade, a barrier beyond which the Chinese were prohibited from settling.[5] Eventually, pressure from Russia on China's Manchurian border lead to a policy change, which saw farmers encouraged to populate the region in a movement of people called Chuang Guandong. In this way, the Qing dynasty expanded the reach of Chinese civilization into formerly sparsely-inhabited tribal domains.

Century of Humiliation

[edit]From the time of the First Opium War with Britain onwards, China lost every battle it fought with foreign powers, was forced into making significant concessions to these powers, and suffered through civil war and uprising and general political unraveling.

China's sphere of influence quickly shrunk in the wake of European colonialism in the 19th and 20th centuries. Most of China's tributaries were conquered by Western powers, while others like Japan and Thailand began a rapid process of Westernization.

Contemporary Period

[edit][[:File:Destroy the old world Cultural Revolution poster.png|thumb|170px|Chinese propaganda poster: "Destroy the old world; Forge the new world." A worker (or possibly Red Guard) crushes the crucifix, Buddha, and classical Chinese texts with his hammer; 1967.]] With the rise of European economic and military power beginning in the mid-19th century, non-Chinese systems of social and political organization gained adherents in China. Some of these would-be reformers totally rejected China's cultural legacy, while others sought to combine the strengths of Chinese and European cultures. In essence, the history of 20th-century China is one of experimentation with new systems of social, political, and economic organization that would allow for the reintegration of the nation in the wake of dynastic collapse.

The Qing Dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China in 1912. In 1949 the People's Republic of China was established towards the end of the Chinese Civil War while the Republic of China retreated to the island of Taiwan.

Communism

[edit]Under Communist rule, Chinese people and Chinese culture underwent a number of radical changes, including the introduction of socialist and Marxist ideology to the mainstream and adoption of Western technology and systems. It became state policy during Chairman Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution to eradicate all symbols and remnants of traditional Chinese culture and all religion in the hope of creating a secular, socialist utopia. (see: http://wiki.riteme.site/wiki/Cultural_revolution#Policy_and_effect) Although the Cultural Revolution was cut short, it resulted in major changes to Chinese culture. Reorientation towards a more Western society increased after the capitalist reforms of Deng Xiaoping in the latter part of the 20th century.

Society

[edit]

Structure

[edit]Since the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors period, some form of Chinese monarch has been the main ruler above all. Different periods of history have different names for the various positions within society. Conceptually each imperial or feudal period is similar, with the government and military officials ranking high in the hierarchy, and the rest of the population under regular Chinese law.[6] From the late Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) onwards, traditional Chinese society was organized into a hierarchic system of socio-economic classes known as the four occupations.

However, this system did not cover all social groups while the distinctions between all groups became blurred ever since the commercialization of Chinese culture in the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). Ancient Chinese education also has a long history; ever since the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE) educated candidates prepared for the Imperial examinations which drafted exam graduates into government as scholar-bureaucrats.

This led to the creation of a meritocracy, although success was available only to males who could afford test preparation. Imperial examinations required applicants to write essays and demonstrate mastery of the Confucian classics. Those who passed the highest level of the exam became elite scholar-officials known as jinshi, a highly esteemed socio-economic position. Trades and crafts were usually taught by a shifu. The female historian Ban Zhao wrote the Lessons for Women in the Han Dynasty and outlined the four virtues women must abide to, while scholars such as Zhu Xi and Cheng Yi would expand upon this. Chinese marriage and Taoist sexual practices are some of the customs and rituals found in society.

Social relations

[edit]Chinese social relations are social relations typified by a reciprocal social network. Often social obligations within the network are characterized in familial terms. The individual link within the social network is known by guanxi (关系/關係) and the feeling within the link is known by the term ganqing (感情). An important concept within Chinese social relations is the concept of face, as in many other Asian cultures. A Buddhist-related concept is yuanfen (缘分/緣分).

As articulated in the sociological works of leading Chinese academic Fei Xiaotong, the Chinese—in contrast to other societies—tend to see social relations in terms of networks rather than boxes. Hence, people are perceived as being "near" or "far" rather than "in" or "out".

Values

[edit]Most social values are derived from Confucianism and Taoism. The subject of which school was the most influential is always debated as many concepts such as Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism and many others have come about. Reincarnation and other rebirth concept is a reminder of the connection between real-life and the after-life. In Chinese business culture, the concept of guanxi, indicating the primacy of relations over rules, has been well documented.[7]

Confucianism was the official philosophy throughout most of Imperial China's history, and mastery of Confucian texts was the primary criterion for entry into the imperial bureaucracy. A number of more authoritarian strains of thought have also been influential, such as Legalism. These philosophies strongly encouraged obedience to the state and communal identity rather than individualism.

There was often conflict between the philosophies, e.g. the Song Dynasty Neo-Confucians believed Legalism departed from the original spirit of Confucianism. Examinations and a culture of merit remain greatly valued in China today. In recent years, a number of New Confucians (not to be confused with Neo-Confucianism) have advocated that democratic ideals and human rights are quite compatible with traditional Confucian "Asian values".[8]

With the rise of European economic and military power beginning in the mid-19th century, non-Chinese systems of social and political organization gained adherents in China. Some of these would-be reformers totally rejected China's cultural legacy, while others sought to combine the strengths of Chinese and European cultures. In essence, the history of 20th-century China is one of experimentation with new systems of social, political, and economic organization that would allow for the reintegration of the nation in the wake of dynastic collapse.

Economic History

[edit]

The economic history of China stretches over thousands of years and has undergone alternating cycles of prosperity and decline. According to the book 'China and the Knowledge Economy: Seizing the 21st century', China was for a large part of the last two millennia the world's largest[9] economy, even though its wealth remained average.[10] China's history is usually divided into three periods: The pre-imperial era, consisting of the era of before the unification of Qin, the early imperial era from Qin to Song, and the late imperial era, marked by the economic revolution that occurred during the Song Dynasty.

By roughly 10,000 BCE, in the Neolithic Era, agriculture was practiced in China. Stratified bronze-age cultures, such as Erlitou, emerged by the third millennium BCE. Under the Shang (c. 1600–1045 BCE) and Zhou (1045–771 BCE), a dependent labor force worked in large-scale foundries and workshops to produce bronzes and silk for the elite. The agricultural surpluses produced by the manorial economy supported these early handicraft industries as well as urban centers and considerable armies. This system began to disintegrate after the collapse of the Western Zhou Dynasty in 771 BCE, preceding the Spring and Autumn and Warring states eras.

As the feudal system collapsed, much legislative power was transferred from the nobility to local kings. A merchant class emerged during the Warring States Period, resulting in increased trade. The new kings established an elaborate bureaucracy, using it to wage wars, build large temples, and perform public works projects. This new system rewarded talent over birthright; important positions were no longer occupied solely by nobility. The adoption of new iron tools revolutionized agriculture and led to a large population increase during this period. By 221 BCE, the state of Qin, which embraced reform more than other states, unified China, built the Great Wall, and set consistent standards of government.[11] Although its draconian laws led to its overthrow in 206 BCE, the Qin institutions survived. During the Han Dynasty, China became a strong, unified, and centralized empire of self-sufficient farmers and artisans, though limited local autonomy remained.

The Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) brought additional economic reforms. Paper money, the compass, and other technological advances facilitated communication on a large scale and the widespread circulation of books. The state's control of the economy diminished, allowing private merchants to prosper and a large increase in investment and profit. Despite disruptions during the Mongol conquest of 1279, the population much increased under the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty, but its GDP per capita remained static since then.[12] In the later Qing period, China's economic development began to slow and Europe's rapid development since the Late Middle Ages[13] and Renaissance[14] enabled it to surpass again China—an event known as the Great Divergence.

Diplomacy

[edit]Sinocentric system

[edit]

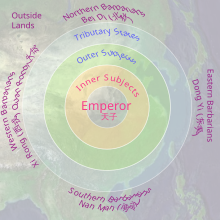

The Sinocentric system was a hierarchical system of international relations that prevailed in East Asia before the adoption of the Westphalian system in modern times. Surrounding countries such as Japan, Korea, the Ryūkyū Kingdom, and Vietnam were regarded as vassals of China and relations between the Chinese Empire and these peoples were interpreted as tributary relationships under which these countries offered tribute (朝貢) to the Emperor of China. Areas outside the Sinocentric influence were called Huawaizhidi (化外之地), meaning uncivilized lands.

At the center of the system stood China, ruled by the dynasty that had gained the Mandate of Heaven. This Celestial Empire (神州 Shénzhōu), distinguished by its Confucian codes of morality and propriety, regarded itself as the only civilization in the world; the Emperor of China (huangdi) was regarded as the only legitimate Emperor of the entire world (lands all under heaven or 天下 tianxia).

Under this scheme of international relations, only China had an Emperor or Huangdi (皇帝), who was the Son of Heaven; other countries only had Kings or Wang (王). (See Chinese sovereign). The Japanese use of the term Heavenly Emperor or 'tennō' (天皇) for the ruler of Japan was a subversion of this principle. Throughout history, the Koreans sometimes refer to their heriarchy as King, conforming with traditional Korean belief of Posterity of Heaven.

Outside the circle of lands directly under Imperial were the tributary states which offered tribute (朝貢) to the Emperor of China and over which China exercised suzerainty. Under the Ming Dynasty, when the tribute system entered its peak, these states were classified into a number of groups. The southeastern barbarians (category one) included some of the major states of East Asia and Southeast Asia, such as Korea, Japan, the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Annam, Đại Việt, Siam, Champa, and Java. A second group of southeastern barbarians covered countries like Sulu, Malacca, and Sri Lanka. Many of these are independent states in modern times.

In addition, there were northern barbarians, northeastern barbarians, and two large categories of western barbarians (from Shanxi, west of Lanzhou, and modern-day Xinjiang), none of which have survived into modern times as separate or independent states.

Beyond the circle of tributary states were countries in a trading relationship with China. The Portuguese, for instance, were allowed to trade with China from leased territory in Macau but did not officially enter the tributary system. Intriguingly, Qing dynasty have used the term Huawaizhidi (化外之地) explicitly for Taiwan (Formosa).[15][16]

While Sinocentrism tends to be identified as a politically inspired system of international relations, in fact it possessed an important economic aspect. The Sinocentric tribute and trade system provided Northeast and Southeast Asia with a political and economic framework for international trade. Countries wishing to trade with China were required to submit to a suzerain-vassal relationship with the Chinese sovereign. After investiture (冊封) of the ruler in question, the missions were allowed to come to China to pay tribute (貢物) to the Chinese emperor. In exchange, tributary missions were presented with return bestowals (回賜). Special licences were issued to merchants accompanying these missions to carry out trade. Trade was also permitted at land frontiers and specified ports. This sinocentric trade zone was based on the use of silver as a currency with prices set by reference to Chinese prices.

The Sinocentric model was not seriously challenged until contact with the European powers in the 18th and 19th century, in particular the Opium War. This was partly due to the fact that there were little direct contact between the Chinese Empire and other empires of the pre-modern period. By the mid 19th century, imperial China was well past its peak and was on the verge of collapse. In the late 19th century, the Sinocentric tributary state system in East Asia was superseded by the Westphalian multi-state system.[17]

Traditional centers of Chinese civilization

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (2012) |

Religion

[edit]

Chinese religion was originally oriented to worshipping the supreme god Shang Di during the Xia and Shang dynasties, with the king and diviners acting as priests and using oracle bones. The Zhou dynasty oriented it to worshipping the broader concept of heaven, and initiated the concept of a Mandate of Heaven which entitled their dynasty to rule. A large part of Chinese culture is based on the notion that a spiritual world exists. Countless methods of divination have helped answer questions, even serving as an alternate to medicine. Folklores have helped fill the gap for things that cannot be explained. There is often a blurred line between myth, religion and unexplained phenomenon.

In Han Dynasty, Confucian ideals were the dominant ideology, and Taoism received official sanction. Near the end of the dynasty, Buddhism entered China and later gained popularity. Historically, Buddhism alternated between state tolerance and even patronage, and persecution. In its original form, Buddhism was at odds with the native Chinese religions, especially the elite, as certain Buddhist values often conflicted with Chinese sensibilities. However, through centuries of assimilation, adaptation, and syncretism, Chinese Buddhism gained an accepted place in the culture. Buddhism would come to be influenced by Confucianism and Taoism,[18] and exerted influence in turn, such as in the form of Neo-Confucianism.

While many deities are part of the tradition, some of the most recognized holy figures include Guan Yin, Jade Emperor and Buddha. Many of the stories have since evolved into traditional Chinese holidays. Other concepts have extended to outside of mythology into spiritual symbols such as Door god and the Imperial guardian lions. Along with the belief of the holy, there is also the evil. Practices such as Taoist exorcism fighting mogwai and jiang shi with peachwood swords are just some of the concepts passed down from generations. A few Chinese fortune telling rituals are still in use today after thousands of years of refinement.

Chinese culture has been long characterized by religious pluralism. The Chinese folk religion has always maintained a profound influence. Indigenous Confucianism and Taoism share aspects of being a philosophy or a religion, and neither demand exclusive adherence, resulting in a culture of tolerance and syncretism where multiple religions or belief systems are often practiced in concert, along with local customs and traditions. Chinese civilization has also been long influenced by Buddhism, while in recent centuries, Christianity has also gained a foothold in the population. Islam has been a significant minority religion in China for several centuries.

Chinese religions

[edit]Confucianism, a governing philosophy and moral code with some religious elements like ancestor worship, is deeply ingrained in Chinese culture and was the official state philosophy in China from the Han Dynasty until the fall of imperial China in the twentieth century.

The Chinese folk religion is the set of worship traditions of the ethnic deities of the Han people. It involves worship of various figures in Chinese mythology, folk heroes such as Guan Yu and Qu Yuan, mythological creatures such as the Chinese dragon, or family, clan and national ancestors. These practices vary from region to region, and do not characterize an organized religion, though many traditional Chinese holidays such as the Duanwu (or Dragon Boat) Festival, Qingming, and the Mid-Autumn Festival come from the most popular of these traditions.

Taoism, another indigenous religion, is also widely practiced in both its folk religion forms and as an organized religion, and has influenced Chinese art, poetry, philosophy, medicine, astronomy, alchemy and chemistry, cuisine, martial arts, and architecture. Taoism was the state religion of the early Han Dynasty, and also often enjoyed state patronage under subsequent emperors and dynasties.

Imported religions

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (2012) |

Others

[edit];

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (2012) |

Islam....

Though Christian influence in China existed as early as the 7th century and Nestorian Christianity received favor during Mongol Yuan Dynasty, Christianity did not begin to gain a significant influence in China until contact with Europeans during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Chinese practices at odds with Christian beliefs resulted in the Chinese Rites controversy, and subsequent reduction in Christian influence. Christianity grew considerably following the First Opium War, after which foreign missionaries in China enjoyed the protection of Western powers, and widespread proselytism took place. AlthoughChristianity was suppressed by the Communist government of China during the Cultural Revolution, significant numbers of Christians exist in China today.

Culture

[edit]China is one of the world's oldest and most complex civilizations. Chinese culture dates back thousands of years. Some Han Chinese believe they share common ancestors, mythically ascribed to the patriarchs Yellow Emperor and Yan Emperor, some thousands of years ago. Hence, some Chinese refer to themselves as "Descendants of Yan and Huang Emperor" (Traditional Chinese: 炎黃子孫; Simplified Chinese: 炎黄子孙), a phrase which has reverberative connotations in a divisive political climate, as in that between mainland China and Taiwan.

Throughout the history of China, Chinese culture has been heavily influenced by Confucianism. Credited with shaping much of Chinese thought, Confucianism was the official philosophy throughout most of Imperial China's history, and mastery of Confucian texts provided the primary criterion for entry into the imperial bureaucracy.

Traditional Chinese Culture covers large geographical territories, where each region is usually divided into distinct sub-cultures. Each region is often represented by three ancestral items. For example Guangdong is represented by chenpi, aged ginger and hay.[19][20] Others include ancient cities like Lin'an (Hangzhou), which include tea leaf, bamboo shoot trunk and hickory nut.[21] Such distinctions give rise to the old Chinese proverb: "十里不同風,百里不同俗/十里不同风,百里不同俗" (Shí lǐ bùtóng fēng, bǎi lǐ bùtóng sú), literally "the wind varies within ten li, customs vary within a hundred li."""

Language and Writing

[edit]

While there are many Chinese dialects, historically there has been greater unity in Chinese written languages. This unity is credited to the Qin dynasty which standardized the various forms of writing that existed in China at that time. For thousands of years, Literary Chinese was used as the standard written format among the literati, which used vocabulary and grammar that may be significantly different from the various forms of spoken Chinese.

During the early twentieth century, written vernacular Chinese based on Beijing Mandarin, which has been developing for a few centuries, was standardized and adopted to replace Literary Chinese. While written vernacular forms of other languages of China exist, such as written Cantonese, written Chinese based on Mandarin is widely understood by speakers of all Chinese languages and has taken up the dominant position among written Chinese languages, formerly occupied by Literary Chinese. Thus, although the residents of different regions would not necessarily understand each other's speech, they generally share a common written language.

By the 20th century, millions of citizens, especially those outside of the "shi da fu" social class were still illiterate.[6] Only after the May 4th Movement did the push for written vernacular Chinese begin. This allowed common citizens to read since it was modeled after the linguistics and phonology of the standard spoken language. Nowadays there are many different dialects among different regions. These dialects are just like "local codes". People could not understand each other if they are not from related areas.

Beginning in the 1950s, Simplified Chinese characters was adopted in mainland China and later in Singapore, while Chinese communities in Hong Kong, Macau, the Republic of China (Taiwan) and overseas countries continue to use Traditional Chinese characters. While significant differences exist between the two character sets, they are largely mutually intelligible.

Numerology

[edit]In Chinese culture, certain numbers are believed by some to be auspicious (吉利) or inauspicious (不利) based on the Chinese word that the number name sounds similar to. However some Chinese people regard these beliefs to be superstitions.

Lucky numbers are based on Chinese words that sound similar to other Chinese words. The numbers 6, 8, and 9 are believed to have auspicious meanings because their names sound similar to words that have positive meanings.

Music

[edit]The music of China dates back to the dawn of Chinese civilization with documents and artifacts providing evidence of a well-developed musical culture as early as the Zhou Dynasty (1122 BCE - 256 BCE). Some of the oldest written music dates back to Confucius's time. The first major well-documented flowering of Chinese music was for the qin during the Tang Dynasty, although the instrument is known to have played a major part before the Han Dynasty.

There are many musical instruments that are integral to Chinese culture, such as the zheng (zither with movable bridges), qin (bridgeless zither), sheng and xiao (vertical flute), the erhu (alto fiddle or bowed lute), pipa (pear-shaped plucked lute), and many others.

Arts

[edit]Different forms of art have swayed under the influence of great philosophers, teachers, religious figures and even political figures. Chinese art encompasses all facets of fine art, folk art and performance art. Porcelain pottery was one of the first forms of art in the Palaeolithic period. Early Chinese music and poetry was influenced by the Book of Songs, and the Chinese poet and statesman Qu Yuan.

Chinese painting became a highly appreciated art in court circles encompassing a wide variety of Shan shui with specialized styles such as Ming Dynasty painting. Early Chinese music was based on percussion instruments, which later gave away to stringed and reed instruments. By the Han dynasty papercutting became a new art form after the invention of paper. Chinese opera would also be introduced and branched regionally in additional to other performance formats such as variety arts.

Traditional medicine

[edit]Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (simplified Chinese: 中医; traditional Chinese: 中醫; pinyin: zhōng yī: "Chinese medicine") is a broad range of medicine practices sharing common theoretical concepts which have been developed in China and are based on a tradition of more than 2,000 years, including various forms of herbal medicine, acupuncture, massage (Tui na), exercise (qigong), and dietary therapy.[22]

The doctrines of Chinese medicine are rooted in books such as the Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon and the Treatise on Cold Damage, as well as in cosmological notions like yin-yang and the five phases. Starting in the 1950s, these precepts were modernized in the People's Republic of China so as to integrate many anatomical and pathological notions from scientific medicine. Nonetheless, many of its assumptions, including the model of the body, or concept of disease, are not supported by modern evidence-based medicine.

TCM's view of the body places little emphasis on anatomical structures, but is mainly concerned with the identification of functional entities (which regulate digestion, breathing, aging etc.). While health is perceived as harmonious interaction of these entities and the outside world, disease is interpreted as a disharmony in interaction. TCM diagnosis consists in tracing symptoms to an underlying disharmony patterns, mainly by palpating the pulse and inspecting the tongue.

Martial arts

[edit]

China is one of the main birth places of Eastern martial arts. Chinese martial arts are collectively given the name Kung Fu ((gong) "achievement" or "merit", and (fu) "man", thus "human achievement") or (previously and in some modern contexts) Wushu ("martial arts" or "military arts"). China also includes the home to the well-respected Shaolin Monastery and Wudang Mountains. The first generation of art started more for the purpose of survival and warfare than art. Over time, some art forms have branched off, while others have retained a distinct Chinese flavor. Regardless, China has produced some of the most renowned martial artists including Wong Fei Hung and many others. The arts have also co-existed with a variety of weapons including the more standard 18 arms. Legendary and controversial moves like Dim Mak are also praised and talked about within the culture.

Cuisine

[edit]

The overwhelmingly large variety of Chinese cuisine comes mainly from the practice of dynastic period, when emperors would host banquets with 100 dishes per meal.[23] A countless number of imperial kitchen staff and concubines were involved in the food preparation process. Over time, many dishes became part of the everyday-citizen culture. Some of the highest quality restaurants with recipes close to the dynastic periods include Fangshan restaurant in Beihai Park Beijing and the Oriole Pavilion.[23] Arguably all branches of Hong Kong eastern style are in some ways rooted from the original dynastic cuisines.

Tea culture

[edit]

Leisure

[edit]A number of games and pastimes are popular within Chinese culture. The most common game is Mah Jong. The same pieces are used for other styled games such as Shanghai Solitaire. Others include pai gow, pai gow poker and other bone domino games. weiqi and xiangqi are also popular. Ethnic games like Chinese yo-yo are also part of the culture.

Names

[edit]Chinese names are typically two or three syllables in length, with the surname preceding the given name. Surnames are typically one character in length, though a few uncommon surnames are two or more syllables long, while given names are one or two syllables long. There are 4,000 to 6,000 surnames in China, of which about 1,000 surnames are most common.

In historical China, hundred surnames (百家姓) was a crucial identity of Han people. Besides the common culture and writings, common origin rooted in the surnames was another major factor that contributed towards Han Chinese identity.[24]

Dress and Fashion

[edit]

Different social classes in different eras boast different fashion trends, the colour yellow or red is usually reserved for the emperor. China's fashion history covers hundreds of years with some of the most colourful and diverse arrangements. During the Qing Dynasty, China's last imperial dynasty dramatic shift of clothing occurred, the clothing of the era before the Qing Dynasty is referred to as Hanfu or traditional Han Chinese clothing. Many symbols such as phoenix have been used for decorative as well as economic purposes.

Today, Han Chinese usually wear Western-style clothing. Few wear traditional Han Chinese clothing on a regular basis. It is, however, preserved in religious and ceremonial costumes. For example, Taoist priests dress in fashion typical of scholars of the Han Dynasty. The ceremonial dress in Japan, such as those of Shinto priests, is largely in line with ceremonial dress in China during the Tang Dynasty. Now, the most popular traditional Chinese clothing worn by many women on important occasions such as wedding banquets and New Year is called the qipao. However, this attire comes not from the Han Chinese but from a modified dress-code of the Manchus, the ethnic group that ruled China between the seventeenth (1644) and the early twentieth century.

Architecture

[edit]

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, British and French expeditionary forces, having marched inland from the coast, reached Peking (Beijing).

Chinese architecture, examples for which can be found from over 2,000 years ago, has long been a hallmark of the culture. There are certain features common to Chinese architecture, regardless of specific region or use. The most important is its emphasis on width, as the wide halls of the Forbidden City serve as an example. In contrast, Western architecture emphasize on height, though there are exceptions such as pagodas.

Another important feature is symmetry, which connotes a sense of grandeur as it applies to everything from palaces to farmhouses. One notable exception is in the design of gardens, which tends to be as asymmetrical as possible. Like Chinese scroll paintings, the principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow, to let the patron wander and enjoy the garden without prescription, as in nature herself. Feng shui has played an important part in structural development.

During the latter portion of the Qing Dynasty, there were cases of blending Chinese and Western architecture, or building primarily in a Western fashion. Portions of the Old Summer Palace are examples of this.

Housing

[edit]Han Chinese housing is different from place to place. Chinese Han people in Beijing traditionally commonly lived with the whole family in large houses that were rectangular in shape. This house is called a 四合院 (traditional and simplified characters) or sì hé yuàn (Hanyu Pinyin). These houses had four rooms in the front: the guest room, kitchen, lavatory, and servants' quarters. Across the large double doors was a wing for the elderly in the family. This wing consisted of three rooms, a central room where the four tablets, heaven, earth, ancestor, and teacher, were worshipped. There the two rooms attached to the left and right were bedrooms for the grandparents. The east wing of the house was inhabited by the eldest son and his family, while the west wing sheltered the second son and his family. Each wing had a veranda, some had a "sunroom" made from a surrounding fabric supported by a wooden or bamboo frame. Every wing is also built around a central courtyard used for study, exercise, or nature viewing.[25]

Literary tradition

[edit]Chinese civilization, being an early center of independent writing, has a rich history of classical literature dating back several thousand years. Important early works include classics texts such as Analects of Confucius, the I Ching, Tao Te Ching, and the Art of War. Some of the most important Han Chinese poets in the pre-modern era include Li Bai, Du Fu, and Su Dongpo. The most important novels in Chinese literature, or the Four Great Classical Novels, are: Dream of the Red Chamber, Water Margin, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and Journey to the West.

Early works

[edit]

Chinese literature began with record keeping and divination on Oracle Bones. The extensive collection of books that have been preserved since the Zhou Dynasty demonstrate just how advanced the intellectuals were at one time. Indeed, the era of the Zhou Dynasty is often looked to as the touchstone of Chinese cultural development. The Five Cardinal Points are the foundation for almost all major studies. Concepts covered within the Chinese classic texts present a wide range of subjects including poetry, astrology, astronomy, calendar, constellations and many others. Some of the most important early texts include I Ching and Shujing within the Four Books and Five Classics. Many Chinese concepts such as Yin and Yang, Qi, Four Pillars of Destiny in relation to heaven and earth were all theorized in the dynastic periods.

The ancient written standard was Classical Chinese. It was used for thousands of years, but was mostly reserved for scholars and intellectuals which forms the "top" class of the society called "shi da fu (士大夫)". Calligraphy later became commercialized, and works by famous artists became prized possessions. Chinese literature has a long past; the earliest classic work in Chinese, the I Ching or "Book of Changes" dates to around 1000 BC. A flourishing of philosophy during the Warring States Period produced such noteworthy works as Confucius's Analects and Laozi's Tao Te Ching. (See also: the Chinese classics.) Dynastic histories were often written, beginning with Sima Qian's seminal Records of the Grand Historian, which was written from 109 BC to 91 BC.

Imperial era

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (2012) |

The Song Dynasty was also a period of great scientific literature, and saw the creation of works such as Su Song's Xin Yixiang Fayao and Shen Kuo's Dream Pool Essays. There were also enormous works of historiography and large encyclopedias, such as Sima Guang's Zizhi Tongjian of 1084 AD or the Four Great Books of Song fully compiled and edited by the 11th century. Notable confucianists, taoists and scholars of all classes have made significant contributions to and from documenting history to authoring saintly concepts that seem hundred of years ahead of time. Many novels such as Four Great Classical Novels spawned countless fictional stories. By the end of the Qing Dynasty, Chinese culture would embark on a new era with written vernacular Chinese for the common citizens. Hu Shih and Lu Xun would be pioneers in modern literature.

The Tang Dynasty witnessed a poetic flowering, while the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature were written during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Printmaking in the form of movable type was developed during the Song Dynasty. Academies of scholars sponsored by the empire were formed to comment on the classics in both printed and handwritten form. Royalty frequently participated in these discussions as well. Chinese philosophers, writers and poets were highly respected and played key roles in preserving and promoting the culture of the empire. Some classical scholars, however, were noted for their daring depictions of the lives of the common people, often to the displeasure of authorities.

Science and technology

[edit]

The history of science and technology in China is both long and rich with many contributions to science and technology. In antiquity, independently of other civilizations, ancient Chinese philosophers made significant advances in science, technology, mathematics, and astronomy. Traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture and herbal medicine were also practiced.

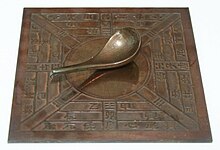

Among the earliest inventions were the abacus, the "shadow clock," and the first items such as Kongming lanterns.[27] The Four Great Inventions: the compass, gunpowder, papermaking, and printing, were among the most important technological advances, only known in Europe by the end of the Middle Ages. The Tang Dynasty (AD 618 - 906) in particular, was a time of great innovation.[27] A good deal of exchange occurred between Western and Chinese discoveries up to the Qing Dynasty.

The Jesuit China missions of the 16th and 17th centuries introduced Western science and astronomy, then undergoing its own revolution, to China, and knowledge of Chinese technology was brought to Europe.[28][29] In the 19th and 20th century the introduction of Western technology was a major factor in the modernization of China. Much of the early Western work in the history of science in China was done by Joseph Needham.

Legacy and Achievements

[edit]Contributions to humanity

[edit]Han Chinese have played a major role in the development of the arts, sciences, philosophy, and mathematics throughout history. In ancient times, the scientific accomplishments of China included seismological detectors, multistage rocket, rocket for recreational and military purposes, gunpowder, fire lance, cannon, landmine, naval mines, continuous flame thrower, fire arrow, trebuchet, crossbow, fireworks, pontoon bridge, matches, paper, printing, paper-printed money, insurance, menu, civil service examination system, the raised-relief map, cartography, biological pest control, the multi-tube seed drill, rotary winnowing fan, cast iron heavy plough, geobotanical prospecting, blast furnace, cast iron, steel, horse collar, petroleum and natural gas as fuel, deep drilling for natural gas, oil drilling, porcelain, lacquer, lacquerware, silk, dry docks, paddle wheels, Stern mounted rudder, the canal lock, Grand Canal, flash lock, water-tight compartments in ships, the double-action piston pump, the magnetic compass, South Pointing Chariot, odometer, fishing reel, Su Song water-driven astronomical clock tower, chain pump, chain drive, escapement, hot air balloon, mechanical clock, belt drive, sliding calipers, pound lock, pendulum, gimbal, collapsible umbrella, trip hammer, kites, sunglasses, toothbrush, inoculation etc. Paper, printing, the compass, and gunpowder are celebrated in Chinese culture as the Four Great Inventions. Chinese astronomers were also among the first to record observations of a supernova.

Chinese art, Chinese cuisine, Chinese philosophy, and Chinese literature all have thousands of years of development, while numerous Chinese sites, such as the Great Wall of China and the Terracotta Army, are World Heritage Sites. Since the start of the program in 2001, aspects of Chinese culture have been listed by UNESCO as Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Sinosphere

[edit]Throughout much of history, successive Chinese Dynasties have exerted influence on their neighbors in the areas of art, music, religion, food, dress, philosophy, language, government, and culture. Although having gone through an immense great deal of change in the last two centuries due to Westernization and modernization on account of European influence and globalization, China and other countries within the so-called "Sinosphere" of countries with strong cultural ties to China are still under influence of the traditional Chinese civilization.

Gallery

[edit]-

The Chinese Dragon, Guardian Lions and incense comprise three symbols within traditional Chinese culture.

-

No. 4 of Ten Thousand Scenes (十萬圖之四). Painting by Ren Xiong, a pioneer of the Shanghai School of Chinese art circa 1850

-

A koi pond is a signature Chinese scenery depicted in countless art work.

-

"Nine Dragons" handscroll section, by Chen Rong, 1244 CE, Chinese Song Dynasty, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

-

Wang Chongyang and the Seven True Daoists of the North

-

Maddison's estimates of GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in 1990 international dollars for selected European and Asian nations between 1500 and 1950,[30] showing the explosive growth of some European nations after 1800.

-

Model of a Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) south-indicating ladle or sinan. It is theorized that the south-pointing spoons of the Han dynasty were magnetized lodestones.[26]

See also

[edit]- Bian Lian

- Sinology

- Chinese Literature

- Chinese Thought

- Chinese name

- Chinese dragon

- Fenghuang

- Chinese dress

- Chinese garden

- Chinese folklore

- Color in Chinese culture

- Numbers in Chinese culture

- Science and technology in China

References

[edit]- ^ "Chinese Dynasty Guide - The Art of Asia - History & Maps". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ^ "Guggenheim Museum - China: 5,000 years". Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation & Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. 6 February 1998 to 1998-06-03. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio (1995). "War and Politics in Ancient China, 2700 B.C. to 722 B.C.". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 39 (3): 471–472.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio (1995). "War and Politics in Ancient China, 2700 B.C. to 722 B.C.". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 39 (3): 471–472.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603–46.

- ^ a b Mente, Boye De. [2000] (2000). The Chinese Have a Word for it: The Complete Guide to Chinese thought and Culture. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-658-01078-6

- ^ Alon, Ilan, ed. (2003), Chinese Culture, Organizational Behavior, and International Business Management, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers.

- ^ Bary, Theodore de. "Constructive Engagement with Asian Values". Archived from the original on 11 March 2005.. Columbia University.

- ^ Dahlman, Carl J; Aubert, Jean-Eric. China and the Knowledge Economy: Seizing the 21st Century. WBI Development Studies. World Bank Publications. Accessed January 30, 2008.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 382, table A.7.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Twitchett pg 54was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 382, table A.7.

- ^ Maddison, Angus: The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective (Vol. 1). Historical Statistics (Vol. 2), OECD 2006, ISBN 92-64-02261-9, p. 629, table 8.3

- ^ Landes, David S.: The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor, W W Norton & Company, New York 1998, ISBN 0-393-04017-8, pp. 29–44

- ^ "History in The Mutan Village Incident". Twhistory.org.tw. 11 June 2001. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Chinataiwan history (历史) of Taiwan area (Chinese)

- ^ Kang, David C. (2010). East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute, p. 160., p. 160, at Google Books

- ^ Jacques Gernet

- ^ Huaxia.com. "Huaxia.com." 廣東三寶之一 禾稈草. Retrieved on 20 June 2009.

- ^ RTHK. "RTHK.org." 1/4/2008 three treasures. Retrieved on 20 June 2009.

- ^ Xinhuanet.com. "Xinhuanet.com." 說三與三寶. Retrieved on 20 June 2009.

- ^ Traditional Chinese Medicine, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine: An Introduction [NCCAM Backgrounder]

- ^ a b Kong, Foong, Ling. [2002]. The Food of Asia. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-7946-0146-4

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Surnames and Han Chinese Identity, University of Washington

- ^ Montgomery County Public Schools Foreign Language Department (08/2006). Si-he-yuan. Montgomery County Public Schools. pp. 1–8.

{{cite conference}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|booktitle=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Selin, Helaine (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. p. 541. ISBN 9781402045592.

The device described by Wang Chong has been widely considered to be the earliest form of the magnetic compass

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Inventionswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Woodswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Agustín Udías, p.53

- ^ Maddison 2007, p. 382, Table A.7

External links

[edit]- Exploring Ancient World Cultures - Ancient China, University of Evansville

- How the Han Chinese became the world's biggest tribe – People's Daily Online Sept 16, 2004

![Maddison's estimates of GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in 1990 international dollars for selected European and Asian nations between 1500 and 1950,[30] showing the explosive growth of some European nations after 1800.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/44/Maddison_GDP_per_capita_1500-1950.svg/120px-Maddison_GDP_per_capita_1500-1950.svg.png)

![Model of a Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) south-indicating ladle or sinan. It is theorized that the south-pointing spoons of the Han dynasty were magnetized lodestones.[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Model_Si_Nan_of_Han_Dynasty.jpg/120px-Model_Si_Nan_of_Han_Dynasty.jpg)