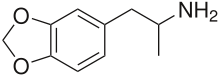

3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | MDA; Tenamfetamine; Amphedoxamine; Sally; Sassafras; Sass-a-frass; Sass; Mellow Drug of America; Hug drug; Love; 3,4-Methylenedioxy-α-methylphenethylamine; 5-(2-Aminopropyl)-1,3-benzodioxole; EA-1298; NSC-9978; NSC-27106; SKF-5 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual, insufflation, intravenous |

| Drug class | Empathogen–entactogen; Stimulant |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP extensively involved) |

| Duration of action | 6–8 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.230.706 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H13NO2 |

| Molar mass | 179.219 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), sometimes referred to as “sass,” is an empathogen-entactogen, stimulant, and psychedelic drug of the amphetamine family that is encountered mainly as a recreational drug. In its pharmacology, MDA is a serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent (SNDRA). In most countries, the drug is a controlled substance and its possession and sale are illegal.

MDA is rarely sought as a recreational drug compared to other amphetamines; however, it remains widely used due to it being a primary metabolite,[2] the product of hepatic N-dealkylation,[3] of MDMA. It is also a common adulterant of illicitly produced MDMA.[4][5]

Uses

[edit]Medical

[edit]MDA currently has no accepted medical use.

Recreational

[edit]MDA is bought, sold, and used as a recreational drug due to its enhancement of mood and empathy.[6] A recreational dose of MDA is sometimes cited as being between 100 and 160 mg.[7]

Overdose

[edit]Symptoms of acute toxicity may include agitation, sweating, increased blood pressure and heart rate, dramatic increase in body temperature, convulsions, and death. Death is usually caused by cardiac effects and subsequent hemorrhaging in the brain (stroke).[8][medical citation needed]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Target | Affinity (Ki, nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 5,600–>10,000 (Ki) 478–4,900 (IC50) 160–162 (EC50) (rat) |

| NET | 13,000 (Ki) 150–420 (IC50) 47–108 (EC50) (rat) |

| DAT | >26,000 (Ki) 890–20,500 (IC50) 106–190 (EC50) (rat) |

| 5-HT1A | 3,762–>10,000 |

| 5-HT1B | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1D | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1E | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1F | ND |

| 5-HT2A | 3,200–>10,000 (Ki) 630–1,767 (EC50) 57–99% (Emax) |

| 5-HT2B | 91–100 (Ki) 190–850 (EC50) 51–80% (Emax) |

| 5-HT2C | 3,000–6,418 (Ki) 98–4,800 (EC50) 79–118% (Emax) |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 |

| 5-HT4 | ND |

| 5-HT5A | >10,000 |

| 5-HT6 | >10,000 |

| 5-HT7 | 3,548 |

| α1A | 8,700–>10,000 |

| α1B | >10,000 |

| α1D | ND |

| α2A | 1,100–2,600 |

| α2B | 690 |

| α2C | 229 |

| β1, β2 | >10,000 |

| D1–D5 | >10,000–>20,000 |

| H1–H4 | >10,000–>13,000 |

| M1–M5 | ND |

| nACh | ND |

| TAAR1 | 220–250 (Ki) (rat) 160–180 (Ki) (mouse) 3,600 (EC50) (human) 11% (Emax) (human) |

| I1 | >10,000 |

| σ1, σ2 | ND |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more avidly the drug binds to the site. Proteins are human unless otherwise specified. Refs: [9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18] | |

MDA is a substrate of the serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and vesicular monoamine transporters, as well as a TAAR1 agonist,[19] and for these reasons acts as a reuptake inhibitor and releasing agent of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine (that is, it is an SNDRA).[20] It is also an agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A,[21] 5-HT2B,[22] and 5-HT2C receptors[23] and shows affinity for the α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-adrenergic receptors and serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 receptors.[24]

The (S)-optical isomer of MDA is more potent than the (R)-optical isomer as a psychostimulant, possessing greater affinity for the three monoamine transporters.

In terms of the subjective and behavioral effects of MDA, it is thought that serotonin release is required for its empathogenic effects, dopamine release is required for its euphoriant (rewarding and addictive) effects, dopamine and norepinephrine release is required for its psychostimulant effects, and direct agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor is required for its mild psychedelic effects.[medical citation needed]

| Compound | Monoamine release (EC50, nM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Serotonin | Norepinephrine | Dopamine | |

| Amphetamine | ND | ND | ND |

| (S)-Amphetamine (d) | 698–1,765 | 6.6–7.2 | 5.8–24.8 |

| (R)-Amphetamine (l) | ND | 9.5 | 27.7 |

| Methamphetamine | ND | ND | ND |

| (S)-Methamphetamine (d) | 736–1,292 | 12.3–13.8 | 8.5–24.5 |

| (R)-Methamphetamine (l) | 4,640 | 28.5 | 416 |

| MDA | 160 | 108 | 190 |

| (S)-MDA (d) | 100 | 50 | 98 |

| (R)-MDA (l) | 310 | 290 | 900 |

| MDMA | 49.6–72 | 54.1–110 | 51.2–278 |

| (S)-MDMA (d) | 74 | 136 | 142 |

| (R)-MDMA (l) | 340 | 560 | 3,700 |

| MDEA | 47 | 2,608 | 622 |

| MBDB | 540 | 3,300 | >100,000 |

| MDAI | 114 | 117 | 1,334 |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more strongly the compound produces the effect. Refs: [25][15][26][27][28][29][30][16] | |||

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The duration of the drug has been reported to be about 6 to 8 hours.[7]

Chemistry

[edit]MDA is a substituted methylenedioxylated phenethylamine and amphetamine derivative. In relation to other phenethylamines and amphetamines, it is the 3,4-methylenedioxy, α-methyl derivative of β-phenylethylamine, the 3,4-methylenedioxy derivative of amphetamine, and the N-desmethyl derivative of MDMA.

Synonyms

[edit]In addition to 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, MDA is also known by other chemical synonyms such as the following:

- α-Methyl-3,4-methylenedioxy-β-phenylethylamine

- 1-(3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-propanamine

- 1-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)-2-propanamine

Synthesis

[edit]MDA is typically synthesized from essential oils such as safrole or piperonal. Common approaches from these precursors include:

- Reaction of safrole's alkene functional group with a halogen containing mineral acid followed by amine alkylation.[31][32]

- Wacker oxidation of safrole to yield 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylpropan-2-one (MDP2P) followed by reductive amination[32][33] or via reduction of its oxime.[34]

- Henry reaction of piperonal with nitroethane followed by nitro compound reduction.[32][35][36][37][38]

- Darzens reaction on heliotropin was also done by J. Elks, et al.[39] This gives MDP2P, which was then subjected to a Leuckart reaction.

- The "two dogs" or "dopeboy" clandestine method, starting with helional as a precursor. First, an oxime is created using hydoxylamine. Then, a Beckmann rearrangement is performed with nickel acetate to form the amide. Then a Hofmann rearrangement is done to form the freebase amine of MDA. Then it is purified with an acid base extraction.[40]

Detection in body fluids

[edit]MDA may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine to monitor for use, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or assist in the forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a sudden death. Some drug abuse screening programs rely on hair, saliva, or sweat as specimens. Most commercial amphetamine immunoassay screening tests cross-react significantly with MDA and major metabolites of MDMA, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish and separately measure each of these substances. The concentrations of MDA in the blood or urine of a person who has taken only MDMA are, in general, less than 10% those of the parent drug.[41][42][43]

Derivatives

[edit]MDA constitutes part of the core structure of the β-adrenergic receptor agonist protokylol.

History

[edit]MDA was first synthesized by Carl Mannich and W. Jacobsohn in 1910.[34] It was first ingested in July 1930 by Gordon Alles who later licensed the drug to Smith, Kline & French.[44] MDA was first used in animal tests in 1939, and human trials began in 1941 in the exploration of possible therapies for Parkinson's disease. From 1949 to 1957, more than five hundred human subjects were given MDA in an investigation of its potential use as an antidepressant and/or anorectic by Smith, Kline & French. The United States Army also experimented with the drug, code named EA-1298, while working to develop a truth drug or incapacitating agent. Harold Blauer died in January 1953 after being intravenously injected, without his knowledge or consent, with 450 mg of the drug as part of Project MKUltra. MDA was patented as an ataractic by Smith, Kline & French in 1960, and as an anorectic under the trade name "Amphedoxamine" in 1961. MDA began to appear on the recreational drug scene around 1963 to 1964. It was then inexpensive and readily available as a research chemical from several scientific supply houses. Several researchers, including Claudio Naranjo and Richard Yensen, have explored MDA in the field of psychotherapy.[45][46]

The International Nonproprietary Name (INN) tenamfetamine was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1986.[47] It was recommended in the same published list in which the INN of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine (DOB), brolamfetamine, was recommended.[47] These events suggest that MDA and DOB were under development as potential pharmaceutical drugs at the time.[47]

Society and culture

[edit]

Name

[edit]When MDA was under development as a potential pharmaceutical drug, it was given the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) of tenamfetamine.[48]

Legal status

[edit]Australia

[edit]MDA is schedule 9 prohibited substance under the Poisons Standards.[49] A schedule 9 substance is listed as a "Substances which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities."[49]

United States

[edit]MDA is a Schedule I controlled substance in the US.

Research

[edit]In 2010, the ability of MDA to invoke mystical experiences and alter vision in healthy volunteers was studied. The study concluded that MDA is a "potential tool to investigate mystical experiences and visual perception".[7]

A 2019 double-blind study administered both MDA and MDMA to healthy volunteers. The study found that MDA shared many properties with MDMA including entactogenic and stimulant effects, but generally lasted longer and produced greater increases in psychedelic-like effects like complex imagery, synesthesia, and spiritual experiences.[50]

Adverse effects

[edit]MDA can produce serotonergic neurotoxic effects in rodents,[51][52] thought to be activated by initial metabolism of MDA.[3] In addition, MDA activates a response of the neuroglia, though this subsides after use.[51]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control]. Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 25 July 2023). 24 July 2023. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Crean RD, Davis SA, Von Huben SN, Lay CC, Katner SN, Taffe MA (October 2006). "Effects of (+/-)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, (+/-)3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine and methamphetamine on temperature and activity in rhesus macaques". Neuroscience. 142 (2): 515–525. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.033. PMC 1853374. PMID 16876329.

- ^ a b de la Torre R, Farré M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, et al. (April 2004). "Human pharmacology of MDMA: pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 26 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00009. PMID 15228154.

- ^ "EcstasyData.org: Test Result Statistics: Substances by Year". EcstasyData.org. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Trans European Drug Information". idpc.net. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Monte AP, Marona-Lewicka D, Cozzi NV, Nichols DE (November 1993). "Synthesis and pharmacological examination of benzofuran, indan, and tetralin analogues of 3,4-(methylenedioxy)amphetamine". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 36 (23): 3700–3706. doi:10.1021/jm00075a027. PMID 8246240.

- ^ a b c Baggott MJ, Siegrist JD, Galloway GP, Robertson LC, Coyle JR, Mendelson JE (December 2010). "Investigating the mechanisms of hallucinogen-induced visions using 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA): a randomized controlled trial in humans". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e14074. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514074B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014074. PMC 2996283. PMID 21152030.

- ^ Diaz J (1996). How Drugs Influence Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- ^ "PDSP Database". UNC (in Zulu). Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ Liu T. "BindingDB BDBM50005247 (+/-)2-Benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-1-methyl-ethylamine::(-)2-Benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-1-methyl-ethylamine::(R)-(-)-2-Benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-1-methyl-ethylamine::(S)-(+)-2-Benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-1-methyl-ethylamine::2-Benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-1-methyl-ethylamine::2-Benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-1-methyl-ethylamine((R)-(-)-MDA)::3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine::CHEMBL6731::MDA::MDA, (R,S)::MDA,R(-)::Tenamfetamine::methylenedioxyamphetamine". BindingDB. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ Ray TS (February 2010). "Psychedelics and the human receptorome". PLOS ONE. 5 (2): e9019. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9019R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009019. PMC 2814854. PMID 20126400.

- ^ Luethi D, Kolaczynska KE, Walter M, Suzuki M, Rice KC, Blough BE, Hoener MC, Baumann MH, Liechti ME (July 2019). "Metabolites of the ring-substituted stimulants MDMA, methylone and MDPV differentially affect human monoaminergic systems". J Psychopharmacol. 33 (7): 831–841. doi:10.1177/0269881119844185. PMC 8269116. PMID 31038382.

- ^ Kolaczynska KE, Ducret P, Trachsel D, Hoener MC, Liechti ME, Luethi D (June 2022). "Pharmacological characterization of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) analogs and two amphetamine-based compounds: N,α-DEPEA and DPIA". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 59: 9–22. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.03.006. PMID 35378384.

- ^ Rickli A, Kopf S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (July 2015). "Pharmacological profile of novel psychoactive benzofurans". Br J Pharmacol. 172 (13): 3412–3425. doi:10.1111/bph.13128. PMC 4500375. PMID 25765500.

- ^ a b Setola V, Hufeisen SJ, Grande-Allen KJ, Vesely I, Glennon RA, Blough B, Rothman RB, Roth BL (June 2003). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy") induces fenfluramine-like proliferative actions on human cardiac valvular interstitial cells in vitro". Mol Pharmacol. 63 (6): 1223–1229. doi:10.1124/mol.63.6.1223. PMID 12761331.

- ^ a b Blough B (July 2008). "Dopamine-releasing agents" (PDF). In Trudell ML, Izenwasser S (eds.). Dopamine Transporters: Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology. Hoboken [NJ]: Wiley. pp. 305–320. ISBN 978-0-470-11790-3. OCLC 181862653. OL 18589888W.

- ^ Brandt SD, Walters HM, Partilla JS, Blough BE, Kavanagh PV, Baumann MH (December 2020). "The psychoactive aminoalkylbenzofuran derivatives, 5-APB and 6-APB, mimic the effects of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) on monoamine transmission in male rats". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 237 (12): 3703–3714. doi:10.1007/s00213-020-05648-z. PMC 7686291. PMID 32875347.

- ^ Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (April 2016). "In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 357 (1): 134–144. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.229765. PMID 26791601.

- ^ Lewin AH, Miller GM, Gilmour B (December 2011). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a stereoselective binding site for compounds in the amphetamine class". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 19 (23): 7044–7048. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.007. PMC 3236098. PMID 22037049.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Therapeutic potential of monoamine transporter substrates". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1845–1859. doi:10.2174/156802606778249766. PMID 17017961.

- ^ Di Giovanni G, Di Matteo V, Esposito E (2008). Serotonin–dopamine Interaction: Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Relevance. Elsevier. pp. 294–. ISBN 978-0-444-53235-0.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (May 2009). "Serotonergic drugs and valvular heart disease". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 8 (3): 317–329. doi:10.1517/14740330902931524. PMC 2695569. PMID 19505264.

- ^ Nash JF, Roth BL, Brodkin JD, Nichols DE, Gudelsky GA (August 1994). "Effect of the R(−) and S(+) isomers of MDA and MDMA on phosphatidyl inositol turnover in cultured cells expressing 5-HT2A or 5-HT2C receptors". Neuroscience Letters. 177 (1–2): 111–115. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(94)90057-4. PMID 7824160. S2CID 41352480.

- ^ Ray TS (February 2010). "Psychedelics and the human receptorome". PLOS ONE. 5 (2): e9019. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9019R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009019. PMC 2814854. PMID 20126400.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Therapeutic potential of monoamine transporter substrates". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1845–1859. doi:10.2174/156802606778249766. PMID 17017961.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Partilla JS (January 2001). "Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin". Synapse. 39 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 11071707. S2CID 15573624.

- ^ Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, Lightfoot-Siordia C, Blough BE (April 2012). "Studies of the biogenic amine transporters. 14. Identification of low-efficacy "partial" substrates for the biogenic amine transporters". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 341 (1): 251–262. doi:10.1124/jpet.111.188946. PMC 3364510. PMID 22271821.

- ^ Marusich JA, Antonazzo KR, Blough BE, Brandt SD, Kavanagh PV, Partilla JS, Baumann MH (February 2016). "The new psychoactive substances 5-(2-aminopropyl)indole (5-IT) and 6-(2-aminopropyl)indole (6-IT) interact with monoamine transporters in brain tissue". Neuropharmacology. 101: 68–75. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.004. PMC 4681602. PMID 26362361.

- ^ Nagai F, Nonaka R, Satoh Hisashi Kamimura K (March 2007). "The effects of non-medically used psychoactive drugs on monoamine neurotransmission in rat brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 559 (2–3): 132–137. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.075. PMID 17223101.

- ^ Halberstadt AL, Brandt SD, Walther D, Baumann MH (March 2019). "2-Aminoindan and its ring-substituted derivatives interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters and α2-adrenergic receptors". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 236 (3): 989–999. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05207-1. PMC 6848746. PMID 30904940.

- ^ Muszynski E (1961). "[Production of some amphetamine derivatives]". Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 18: 471–478. PMID 14477621.

- ^ a b c Shulgin A, Manning T, Daley P (2011). The Shulgin Index, Volume One: Psychedelic Phenethylamines and Related Compounds (1 ed.). Berkeley, CA: Transform Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-9630096-3-0.

- ^ Noggle FT, DeRuiter J, Long MJ (1986). "Spectrophotometric and liquid chromatographic identification of 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylisopropylamine and its N-methyl and N-ethyl homologs". Journal of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 69 (4): 681–686. PMID 2875058.

- ^ a b Mannich C, Jacobsohn W, Mannich HC (1910). "Über Oxyphenyl-alkylamine und Dioxyphenyl-alkylamine". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 41 (1): 189–197. doi:10.1002/cber.19100430126.

- ^ Ho BT, McIsaac WM, An R, Tansey LW, Walker KE, Englert LF, Noel MB (January 1970). "Analogs of alpha-methylphenethylamine (amphetamine). I. Synthesis and pharmacological activity of some methoxy and/or methyl analogs". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1021/jm00295a007. PMID 5412110.

- ^ Butterick JR, Unrau AM (1974). "Reduction of β-nitrostyrene with sodium bis-(2-methoxyethoxy)-aluminium dihydride. A convenient route to substituted phenylisopropylamines". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 8 (8): 307–308. doi:10.1039/C39740000307.

- ^ Toshitaka O, Hiroaka A (1992). "Synthesis of Phenethylamine Derivatives as Hallucinogen". Japanese Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 38 (6): 571–580. doi:10.1248/jhs1956.38.571. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Shulgin A, Shulgin A (1991). PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. Lafayette, CA: Transform Press. ISBN 978-0-9630096-0-9.

- ^ Elks J, Hey DH (1943). "7. β-3 : 4-Methylenedioxyphenylisopropylamine". J. Chem. Soc.: 15–16. doi:10.1039/JR9430000015. ISSN 0368-1769.

- ^ "Does the 'Two Dogs' Method of Clandestine Synthesis Use Precursors That are not Legally Regulated on the Australian East Coast? by Victor Chiruta, Robert D Renshaw :: SSRN". 28 November 2021. SSRN 3973132. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Kolbrich EA, Goodwin RS, Gorelick DA, Hayes RJ, Stein EA, Huestis MA. Plasma pharmacokinetics of 3,4-methyl

enedioxy methamphetamine after controlled oral administration to young adults. Ther. Drug Monit. 30: 320–332, 2008. - ^ Barnes AJ, De Martinis BS, Gorelick DA, Goodwin RS, Kolbrich EA, Huestis MA (March 2009). "Disposition of MDMA and metabolites in human sweat following controlled MDMA administration". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (3): 454–462. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.117093. PMC 2669283. PMID 19168553.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 9th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, California, 2011, pp. 1078–1080.

- ^ "The First MDA trip and the measurement of 'mystical experience' after MDA, LSD, and Psilocybin". Psychedelic research. 18 July 2008. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012.

- ^ Naranjo C, Shulgin AT, Sargent T (1967). "Evaluation of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) as an adjunct to psychotherapy". Medicina et Pharmacologia Experimentalis. International Journal of Experimental Medicine. 17 (4): 359–364. doi:10.1159/000137100. PMID 5631047.

- ^ Yensen R, Di Leo FB, Rhead JC, Richards WA, Soskin RA, Turek B, Kurland AA (October 1976). "MDA-assisted psychotherapy with neurotic outpatients: a pilot study". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 163 (4): 233–245. doi:10.1097/00005053-197610000-00002. PMID 972325. S2CID 41155810.

- ^ a b c "INN Recommended List 26". World Health Organization (WHO). 9 June 1986. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Elks J (2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer US. p. 1157. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ a b Poisons Standard (October 2015) comlaw.gov.au

- ^ Baggott MJ, Garrison KJ, Coyle JR, Galloway GP, Barnes AJ, Huestis MA, Mendelson JE (15 March 2019). "Effects of the Psychedelic Amphetamine MDA (3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine) in Healthy Volunteers". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 51 (2): 108–117. doi:10.1080/02791072.2019.1593560. PMID 30967099. S2CID 106410946.

- ^ a b Herndon JM, Cholanians AB, Lau SS, Monks TJ (March 2014). "Glial cell response to 3,4-(+/-)-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and its metabolites". Toxicological Sciences. 138 (1): 130–138. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kft275. PMC 3930364. PMID 24299738.

- ^ Kalant H (October 2001). "The pharmacology and toxicology of "ecstasy" (MDMA) and related drugs". CMAJ. 165 (7): 917–928. PMC 81503. PMID 11599334.

External links

[edit]- Drugs not assigned an ATC code

- 5-HT2A agonists

- 5-HT2B agonists

- 5-HT2C agonists

- Benzodioxoles

- Entactogens and empathogens

- Euphoriants

- Human drug metabolites

- Human pathological metabolites

- Monoaminergic neurotoxins

- Psychedelic drugs

- Recreational drug metabolites

- Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agents

- Serotonin receptor agonists

- Stimulants

- Substituted amphetamines

- TAAR1 agonists

- VMAT inhibitors