Pentobarbital

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

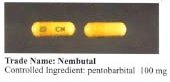

| Trade names | Nembutal |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682416 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, intramuscular, rectal |

| Drug class | Barbiturate |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 70–90% (oral); 90% (rectal) |

| Protein binding | 20–45% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 15–48 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.895 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H18N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 226.276 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Pentobarbital (US) or pentobarbitone (British and Australian) is a short-acting barbiturate typically used as a sedative, a preanesthetic, and to control convulsions in emergencies.[3] It can also be used for short-term treatment of insomnia but has been largely replaced by the benzodiazepine family of drugs.

In high doses, pentobarbital causes death by respiratory arrest. It is used for veterinary euthanasia and is used by some US states and the United States federal government for executions of convicted criminals by lethal injection.[4] In some countries and states, it is also used for physician-assisted suicide.[5][6]

Pentobarbital was widely abused beginning in the late 1930s and sometimes known as "yellow jackets" due to the yellow color of Nembutal-branded capsules.[7] Pentobarbital in oral (pill) form is not commercially available.[4][failed verification]

Pentobarbital was developed by Ernest H. Volwiler and Donalee L. Tabern at Abbott Laboratories in 1930.

Uses

[edit]Medical

[edit]Typical applications for pentobarbital are sedative, short term hypnotic, preanesthetic, insomnia treatment, and control of convulsions in emergencies.[3] Abbott Pharmaceutical discontinued manufacture of their Nembutal brand of Pentobarbital capsules in 1999, largely replaced by the benzodiazepine family of drugs.

Pentobarbital can reduce intracranial pressure in Reye's syndrome, treat traumatic brain injury and induce coma in cerebral ischemia patients.[8] Pentobarbital-induced coma has been advocated in patients with acute liver failure refractory to mannitol.[9]

Pentobarbital is also used as a veterinary anesthetic agent.[10]

Euthanasia and assisted suicide

[edit]Pentobarbital can cause death when used in high doses. It is used for euthanasia for humans as well as animals. It is taken alone, or in combination with complementary agents such as phenytoin, in commercial animal euthanasia injectable solutions.[5][6]

In the Netherlands, pentobarbital is part of the standard protocol for physician-assisted suicide for self-administration by the patient.[11] It is given in liquid form, in a solution of sugar syrup and alcohol, containing 9 grams of pentobarbital. This is preceded by an antiemetic to prevent vomiting.[11]

It is taken by mouth for physician-assisted death in the United States states of Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and California (as of January 2016).[12][13] The oral dosage of pentobarbital indicated for physician-assisted suicide in Oregon is typically 10 g of liquid.[12][13]

In Switzerland, sodium pentobarbital is administered to the patient intravenously. Once administered, sleep is induced within 30 seconds, and the heart stops beating within 3 minutes.[14] Oral administration is also used. A Swiss pharmacist reported in 2022 that the dose for assisted suicide had been raised to 15 grams because with lower doses death was preceded by a coma of up to 10 hours in some cases.[15]

Execution

[edit]Pentobarbital has been used or considered as a substitute for the barbiturate sodium thiopental used for capital punishment by lethal injection in the United States when that drug became unavailable.[16] In 2011 the U.S. manufacturer of sodium thiopental stopped production, and importation of the drug proved impossible. Pentobarbital was used in a U.S. execution for the first time in December 2010 in Oklahoma, as part of a three-drug protocol.[16] In March 2011 pentobarbital was used for the first time as the sole drug in a U.S. execution, in Ohio. Since then several states as well as the federal government have used pentobarbital for lethal injections; some use three-drug protocols and others use pentobarbital alone.

Pentobarbital is produced by the Danish company Lundbeck. Use of the drug for executions is illegal under Danish law, and when this was discovered, after public outcry in Danish media, Lundbeck stopped selling it to US states that impose the death penalty and prohibited US distributors from selling it to any customers, such as state authorities, that practice or participate in executions of humans.[17]

Texas began using the single-drug pentobarbital protocol for executing death-row inmates on 18 July 2012,[18] because of a shortage of pancuronium bromide, a muscle paralytic previously used as one component of a three-drug cocktail.[18] In October 2013, Missouri changed its protocol to allow for pentobarbital from a compounding pharmacy to be used in a lethal dose for executions.[19] It was first used in November 2013.[20][21]

According to a December 2020 ProPublica article, by 2017 the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), in discussion with then Attorney General Jeff Sessions, had begun to search for suppliers of pentobarbital to be used in lethal injections. The BOP was aware that the use of pentobarbital as their "new drug choice" would be challenged in the courts because some lawyers had said that "pentobarbital would flood prisoners' lungs with froth and foam, inflicting pain and terror akin to a death by drowning." BOP claimed that these concerns were unjustified and that their two expert witnesses asserted that the use of pentobarbital was "humane".[22] On 25 July 2019, US Attorney General William Barr directed the federal government to resume capital punishment after 16 years.[23] The federal protocol provides for intravenous administration of two syringes each containing 2.5 grams of pentobarbital sodium followed by a saline flush.[24]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Like other barbiturates, pentobarbital binds to the barbiturate-binding site on the GABA-A receptor. This action increases the duration of ion-channel opening. At high doses, pentobarbital is capable of opening the ion channel in the absence of GABA.[25]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Pentobarbital undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver and possibly the intestines.[26]

Drug interactions

[edit]Administration of ethanol, benzodiazepines, opioids, antihistamines, other sedative-hypnotics, and other central nervous system depressants will cause possible additive effects.[8]

Chemistry

[edit]Pentobarbital is synthesized by methods analogous to that of amobarbital, the only difference being that the alkylation of α-ethylmalonic ester is carried out with 2-bromopentane in place of 1-bromo-3-methylbutane to give pentobarbital.[27][28][29]

Pentobarbital can occur as a free acid but is usually formulated as the sodium salt, pentobarbital sodium. The free acid is only slightly soluble in water and in ethanol[30][31] while the sodium salt shows better solubility.

Society and culture

[edit]Pentobarbital is the INN, AAN, BAN, and USAN while pentobarbitone is a former AAN and BAN.

One brand name for this drug is Nembutal, coined by John S. Lundy, who started using it in 1930, from the structural formula of the sodium salt—Na (sodium) + ethyl + methyl + butyl + al (common suffix for barbiturates).[32] Nembutal is trademarked and manufactured by the Danish pharmaceutical company Lundbeck (now produced by Akorn Pharmaceuticals) is the only injectable form of pentobarbital approved for sale in the United States.

Abbott discontinued its Nembutal brand of pentobarbital capsules in 1999, largely replaced by the benzodiazepine family of drugs. Abbott's Nembutal, known on the streets as "yellow jackets", was widely abused.[33][34] They were available as 30, 50, and 100 mg capsules of yellow, white-orange, and yellow colors, respectively.[35]

References

[edit]- ^ "Therapeutic Goods (Poisons Standard—June 2024) Instrument 2024". 30 May 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Nembutal sodium- pentobarbital sodium injection". DailyMed. 31 December 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ a b Palmer K (28 October 2013). "Ohio says it will switch to new drugs for executions". Reuters.

- ^ a b Chaar B, Sami Isaac S (20 October 2017). "Euthanasia drugs: What is needed from medications for assisted deaths?". abc.net.au. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

Both secobarbital capsules and pentobarbital (usually known as the brand name, Nembutal) liquid — (not to be mistaken for epilepsy medication phenobarbital) have been used either alone or in combination for physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia. They are also used in injectable forms for animal euthanasia.

- ^ a b Martin H (13 August 2020). "Euthanasia referendum: What drugs are used in assisted dying, and how do they work?". Stuff. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

In Australia, most people will ingest the lethal dose of pentobarbital as a drink – a white powder mixed with about 30 millilitres of a liquid suspension. [...] However, in cases where the person is too ill to ingest the medication themselves, a doctor or nurse practitioner could administer the dose, under the proposed Act.

- ^ Cozanitis, Dimitri A (December 2004). "One hundred years of barbiturates and their saint". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (12): 594–598. doi:10.1177/014107680409701214. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 1079678. PMID 15574863.

- ^ a b "Pentobarbital" (Monograph). Drugs.com. AHFS.

- ^ Stravitz RT, Kramer AH, Davern T, Shaikh AO, Caldwell SH, Mehta RL, et al. (November 2007). "Intensive care of patients with acute liver failure: recommendations of the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group". Critical Care Medicine. 35 (11): 2498–2508. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000287592.94554.5F. PMID 17901832. S2CID 11924124.

- ^ "Pentobarbital". Drugs.com.

- ^ a b Köhler W (23 November 2000). "Euthanica". Euthanesia Dossier (in Dutch). NRC Webpagina's.

- ^ a b Fass J, Fass A (May 2011). "Physician-assisted suicide: ongoing challenges for pharmacists". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 68 (9): 846–849. doi:10.2146/ajhp100333. PMID 21515870.

- ^ a b Philip N, Stewart F (2006). The Peaceful Pill Handbook. Exit International US Ltd. p. 137. ISBN 0978878809 – via Google Books.

- ^ Assisted dying in Switzerland (Video), Dying with Dignity in Canada, 15 February 2022, 39:00 min - 41:19 min, retrieved 6 November 2022

- ^ Keller M (22 May 2022). "Assistierter Suizid in der Schweiz - Sterben auf Wunsch" [Assisted suicide in Switzerland - dying on request]. Deutschlandfunk (in German). Deutschlandradio. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ a b Mears B (21 May 2012). "States urge feds to help import lethal injection drugs". CNN.

- ^ Sanburn J (7 August 2013). "The Hidden Hand Squeezing Texas' Supply of Execution Drugs". Time.

- ^ a b "Texas executes Yokamon Hearn with pentobarbitol". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 18 July 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ Lewis A (15 November 2013). "Lethal injection: Secretive US states resort to untested drugs". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Salter J (20 November 2013). "Missouri executes serial killer Franklin". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013.

- ^ Martin SK (20 November 2013). "Joseph Paul Franklin Executed; First MO Inmate Killed Using Pentobarbital". Christian Post.

- ^ Arnsdorf I (23 December 2020). "Inside Trump and Barr's Last-Minute Killing Spree". ProPublica. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Williams P, Arkin D (25 July 2019). "AG Barr orders reinstatement of the federal death penalty". NBC News.

- ^ Notice of Adoption of Revised Protocol, U.S. Department of Justice, 25 July 2019

- ^ Baer AB, Holstege CP (January 2005). "Barbiturates, Long-Acting". In Wexler P (ed.). Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Second ed.). New York: Elsevier. pp. 209–210. doi:10.1016/b0-12-369400-0/00104-6. ISBN 978-0-12-369400-3.

- ^ Knodell RG, Spector MH, Brooks DA, Keller FX, Kyner WT (December 1980). "Alterations in pentobarbital pharmacokinetics in response to parenteral and enteral alimentation in the rat". Gastroenterology. 79 (6): 1211–1216. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(80)90915-4. PMID 6777235.

- ^ Volwiler EH, Tabern DL (1930). "5,5-Substituted Barbituric Acids1". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 52 (4): 1676–1679. doi:10.1021/ja01367a061.

- ^ Kaiserliches Patentamt German imperial patent, D.R.P. 293163 (16 July 1916), Bayer& Co

- ^ GB patent 650354, Wilde BE, Balaban IE, "Improvements in the manufacture of substituted barbituric and thiobarbituric acids", issued 21 February 1951, assigned to Geigy

- ^ "Pentobarbital Compound summary". PubChem. U.S National Library of Medicine. CID4737.

- ^ "FR1972_08_25_17226" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2016.

- ^ Fosburgh LC (August 1997). "From this point in time: some memories of my part in the history of anesthesia--John S. Lundy, MD". AANA Journal. 65 (4): 323–328. PMID 9281913.

- ^ Jolly D (1 July 2011). "Danish Company Blocks Sale of Drug for U.S. Executions". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Aldrich MR, Ashley R, Horowitz M (1978). High Times Encyclopedia of Recreational Drugs. New York: Stonehill. p. 243. ISBN 0-88373-082-0. OCLC 4557439.

- ^ Physicians' Desk Reference (33rd ed.). Oradell, New Jersey: Medical Economics Co. 1979. p. 403. ISBN 0-87489-999-0. OCLC 4636066.