Tasmania

Tasmania | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Nickname(s):

| ||||

| Motto: | ||||

Location of Tasmania in Australia Coordinates: 42°S 147°E / 42°S 147°E | ||||

| Country | Australia | |||

| Before federation | Colony of Tasmania | |||

| Federation | 1 January 1901 | |||

| Named for | Abel Tasman | |||

| Capital and largest city | Hobart 42°52′50″S 147°19′30″E / 42.88056°S 147.32500°E | |||

| Administration | 29 local government areas | |||

| Demonym(s) | ||||

| Government | ||||

• Monarch | Charles III | |||

• Governor | Barbara Baker | |||

• Premier | Jeremy Rockliff (Liberal) | |||

| Legislature | Parliament of Tasmania | |||

| Legislative Council | ||||

| House of Assembly | ||||

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Tasmania | |||

| Parliament of Australia | ||||

• Senate | 12 senators (of 76) | |||

| 5 seats (of 151) | ||||

| Area | ||||

• Total | 68,402 km2 (26,410 sq mi) (7th) | |||

| Highest elevation | 1,617 m (5,305 ft) | |||

| Population | ||||

• March 2022 estimate | ||||

• Density | 8.9/km2 (23.1/sq mi) (4th) | |||

| GSP | 2020 estimate | |||

• Total | ||||

• Per capita | ||||

| Gini (2016) | 44.8[6] medium · 3rd | |||

| HDI (2021) | very high · 8th | |||

| Time zone | UTC+10:00 (AEST) | |||

• Summer (DST) | UTC+11:00 (AEDT) | |||

| Postal abbreviation | TAS | |||

| ISO 3166 code | AU-TAS | |||

| Symbols | ||||

| Bird | Yellow wattlebird (unofficial) (Anthochaera paradoxa)[9] | |||

| Flower | Tasmanian blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus)[10] | |||

| Mammal | Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii)[8] | |||

| Plant | Leatherwood (unofficial) (Eucryphia lucida)[11] | |||

| Colour(s) | Bottle Green (PMS 342), Yellow (PMS 114), & Maroon (PMS 194)[12] | |||

| Mineral | Crocoite (PbCrO4)[13] | |||

| Website | tas | |||

Tasmania (/tæzˈmeɪniə/; palawa kani: lutruwita[14]) is an island state of Australia.[15] It is located 240 kilometres (150 miles) to the south of the Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The state encompasses the main island of Tasmania, the 26th-largest island in the world, and the surrounding 1000 islands.[16] It is Australia's smallest and least populous state, with 573,479 residents as of June 2023[update]. The state capital and largest city is Hobart, with around 40% of the population living in the Greater Hobart area.[17] Tasmania is the most decentralised state in Australia, with the lowest proportion of its residents living within its capital city.[18]

Tasmania's main island was inhabited by Aboriginal peoples.[19] It is thought that Aboriginal Tasmanians became separated from the mainland Aboriginal groups about 11,700 years ago, after rising sea levels formed Bass Strait.[20] The island was permanently settled by Europeans in 1803 as a penal settlement of the British Empire to prevent claims to the land by the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.[21] The Aboriginal population is estimated to have been between 3,000 and 7,000 at the time of British settlement, but was almost wiped out within 30 years during a period of conflicts with settlers known as the "Black War" and the spread of infectious diseases. The conflict, which peaked between 1825 and 1831 and led to more than three years of martial law, killed almost 1,100 Aboriginal people and settlers.

Under British rule, the island was initially part of the Colony of New South Wales; however, it became a separate colony under the name Van Diemen's Land (named after Anthony van Diemen) in 1825.[22] Approximately 80,000 convicts were sent to Van Diemen's Land before this practice, known as transportation, ceased in 1853.[23] In 1855, the present Constitution of Tasmania was enacted, and the following year the colony formally changed its name to Tasmania. In 1901, it became a state of Australia through the process of the federation of Australia.

Today, Tasmania has the second smallest economy of the Australian states and territories, and comprises principally tourism, agriculture, aquaculture, education, and healthcare.[24] Tasmania is a significant agricultural exporter, as well as a significant destination for eco-tourism. About 42% of its land area, including national parks and World Heritage Sites (21%), is protected in some form of reserve.[25] The first environmental political party in the world was founded in Tasmania.[26]

Toponymy

Tasmania is named after Dutch explorer Abel Tasman, who made the first reported European sighting of the island on 24 November 1642. Tasman named the island Anthony van Diemen's Land after his sponsor Anthony van Diemen, the Governor of the Dutch East Indies. The name was later shortened to Van Diemen's Land by the British. It was officially renamed "Tasmania" in honour of its first European discoverer on 1 January 1856.[27]

Tasmania was sometimes referred to as "Dervon", as mentioned in the Jerilderie Letter written by the notorious Australian bushranger Ned Kelly in 1879. The colloquial expression for the state is "Tassie". Tasmania is also colloquially shortened to "Tas", mainly when used in business names and website addresses. TAS is also the Australia Post abbreviation for the state.

In the constructed palawa kani language, the main island of Tasmania is called "lutruwita",[28] a name originally derived from the Bruny Island Tasmanian language. George Augustus Robinson recorded it as Loe.trou.witter and also as Trow.wer.nar, probably from one or more of the eastern or Northeastern Tasmanian languages. However, he also recorded it as a name for Cape Barren Island. In the 20th century, some writers used it as an Aboriginal name for Tasmania, spelled "Trowenna" or "Trowunna". It is now believed that the name is more properly applied to Cape Barren Island,[28] which has had an official dual name of "Truwana" since 2014.[29]

A number of palawa kani names, based on historical records of aboriginal names, have been accepted by the Tasmanian government. A dozen of these (below) are 'dual-use' (bilingual) names, and another two are unbounded areas with only palawa names.[30]

- Bilingual names

- kanamaluka / Tamar River

- kunanyi / Mount Wellington

- laraturunawn / Sundown Point

- nungu / West Point

- pinmatik / Rocky Cape

- takayna / The Tarkine

- taypalaka / Green Point

- titima / Trefoil Island

- truwana / Cape Barren Island

- wukalina / Mount William

- yingina / Great Lake

- Palawa names

- larapuna: an unbounded area centred on the Bay of Fires

- Narawntapu National Park (formerly Asbestos Range National Park)

- putalina: an unbounded area centred on Oyster Cove (including the community of Oyster Cove)

There are also a number of archaeological sites with Palawa names. Some of these names have been contentious, with names being proposed without consultation with the aboriginal community, or without having a connection to the place in question.[31]

As well as a diverse First Nations geography, where remnants are preserved in rough form by European documentation, Tasmania is known as a place for unorthodox place-names.[32] These names often come about from lost definitions, where descriptive names have lost their old meanings and have taken on new modern interpretations (e.g. 'Bobs Knobs'). Other names have retained their original meaning, and are often quaint or endearing descriptions (e.g. 'Paradise').

History

Physical history

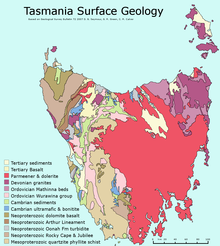

The island was adjoined to the mainland of Australia until the end of the last glacial period about 11,700 years ago.[20] Much of the island is composed of Jurassic dolerite intrusions (the upwelling of magma) through other rock types, sometimes forming large columnar joints. Tasmania has the world's largest areas of dolerite, with many distinctive mountains and cliffs formed from this rock type. The central plateau and the southeast portions of the island are mostly dolerites. Mount Wellington above Hobart is a good example, showing distinct columns known as the Organ Pipes.

In the southern midlands as far south as Hobart, the dolerite is underlaid by sandstone and similar sedimentary stones. In the southwest, Precambrian quartzites were formed from very ancient sea sediments and form strikingly sharp ridges and ranges, such as Federation Peak or Frenchmans Cap.

In the northeast and east, continental granites can be seen, such as at Freycinet, similar to coastal granites on mainland Australia. In the northwest and west, mineral-rich volcanic rock can be seen at Mount Read near Rosebery, or at Mount Lyell near Queenstown. Also present in the south and northwest is limestone with caves.

The quartzite and dolerite areas in the higher mountains show evidence of glaciation, and much of Australia's glaciated landscape is found on the Central Plateau and the Southwest. Cradle Mountain, another dolerite peak, for example, was a nunatak. The combination of these different rock types contributes to scenery which is distinct from any other region of the world.[citation needed] In the far southwest corner of the state, the geology is almost wholly quartzite, which gives the mountains the false impression of having snow-capped peaks year round.

Aboriginal people

Evidence indicates the presence of Aboriginal people in Tasmania about 42,000 years ago. Rising sea levels cut Tasmania off from mainland Australia about 10,000 years ago and by the time of European contact, the Aboriginal people in Tasmania had nine major nations or ethnic groups.[33] At the time of the British occupation and colonisation in 1803, the indigenous population was estimated at between 3,000 and 10,000.

Historian Lyndall Ryan's analysis of population studies led her to conclude that there were about 7,000 spread throughout the island's nine nations;[34] Nicholas Clements, citing research by N.J.B. Plomley and Rhys Jones, settled on a figure of 3,000 to 4,000.[35] They engaged in fire-stick farming, hunted game including kangaroo and wallabies, caught seals, mutton-birds, shellfish and fish and lived as nine separate "nations" on the island, which they knew as "Trouwunna".

European arrival and governance

The first reported sighting of Tasmania by a European was on 24 November 1642 by Dutch explorer Abel Tasman, who landed at today's Blackman Bay. More than a century later, in 1772, a French expedition led by Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne landed at (nearby but different) Blackmans Bay, and the following year Tobias Furneaux became the first Englishman to land in Tasmania when he arrived at Adventure Bay, which he named after his ship HMS Adventure. Captain James Cook also landed at Adventure Bay in 1777. Matthew Flinders and George Bass sailed through Bass Strait in 1798–1799, determining for the first time that Tasmania was an island.[36]

Sealers and whalers based themselves on Tasmania's islands from 1798,[37] and in August 1803 New South Wales Governor Philip King sent Lieutenant John Bowen to establish a small military outpost on the eastern shore of the Derwent River in order to forestall any claims to the island by French explorers who had been exploring the southern Australian coastline. Bowen, who led a party of 49, including 21 male and three female convicts, named the camp Risdon.[36][38]

Several months later, a second settlement was established by Captain David Collins, with 308 convicts, 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) to the south in Sullivans Cove on the western side of the Derwent, where fresh water was more plentiful. The latter settlement became known as Hobart Town or Hobarton, later shortened to Hobart, after the British Colonial Secretary of the time, Lord Hobart. The settlement at Risdon was later abandoned. Left on their own without further supplies, the Sullivans Cove settlement suffered severe food shortages and by 1806 its inhabitants were starving, with many resorting to scraping seaweed off rocks and scavenging washed-up whale blubber from the shore to survive.[36]

A smaller colony was established at Port Dalrymple on the Tamar River in the island's north in October 1804 and several other convict-based settlements were established, including the particularly harsh penal colonies at Port Arthur in the southeast and Macquarie Harbour on the West Coast. Tasmania was eventually sent 75,000 convicts—four out of every ten people transported to Australia.[36] By 1819, the Aboriginal and British population reached parity with about 5000 of each, although among the colonists men outnumbered women four-to-one.[39] Free settlers began arriving in large numbers from 1820, lured by the promise of land grants and free convict labour. Settlement in the island's northwest corner was monopolised by the Van Diemen's Land Company, which sent its first surveyors to the district in 1826. By 1830, one-third of Australia's non-Indigenous population lived in Van Diemen's Land and the island accounted for about half of all land under cultivation and exports.[40]

Black War

Tensions between Tasmania's Aboriginal and white inhabitants rose, partly driven by increasing competition for kangaroo and other game.[41][42][43] Explorer and naval officer John Oxley in 1810 noted the "many atrocious cruelties" inflicted on Aboriginal people by convict bushrangers in the north, which in turn led to black attacks on solitary white hunters.[44] Hostilities increased further with the arrival of 600 colonists from Norfolk Island between 1807 and 1813. They established farms along the River Derwent and east and west of Launceston, occupying ten percent of Van Diemen's Land. By 1824 the colonial population had swelled to 12,600, while the island's sheep population had reached 200,000. The rapid colonisation transformed traditional kangaroo hunting grounds into farms with grazing livestock as well as fences, hedges and stone walls, while police and military patrols were increased to control the convict farm labourers.[45]

Violence began to spiral rapidly from the mid-1820s in what became described as the "Black War".[46] Aboriginal inhabitants were driven to desperation by hunger – that included a desire for agricultural produce, as well as feeling anger at the prevalence of abductions of women and girls. New settlers motivated by fear carried out self-defence operations as well as attacks as a means of suppressing the native threat – or even in some cases, exacting revenge.[47] Van Diemen's Land had an enormous gender imbalance, with male colonists outnumbering females six to one in 1822—and 16 to one among the convict population. Historian Nicholas Clements has suggested the "voracious appetite" for native women was the most important trigger for the explosion of violence from the late 1820s.[48]

From 1825 to 1828, the number of native attacks more than doubled each year, raising panic among settlers. Over the summer of 1826–1827 clans from the Big River, Oyster Bay and North Midlands nations speared stock-keepers on farms and made it clear that they wanted the settlers and their sheep and cattle to move from their kangaroo hunting grounds. Settlers responded vigorously, resulting in many mass-killings. In November 1826, Governor Sir George Arthur issued a government notice declaring that colonists were free to kill Aboriginal people when they attacked settlers or their property, and in the following eight months more than 200 Aboriginal people were killed in the Settled Districts in reprisal for the deaths of 15 colonists. After another eight months, the death toll had risen to 43 colonists and probably 350 Aboriginal people.[49] In April 1828, Arthur issued a Proclamation of Demarcation forbidding Aboriginal people to enter the settled districts without a passport issued by the government.[50][51] Arthur declared martial law in the colony in November that year, and this remained in force for over three years, the longest period of martial law in Australian history.[52][53]

In November 1830, Arthur organised the so-called "Black Line", ordering every able-bodied male colonist to assemble at one of seven designated places in the Settled Districts to join a massive drive to sweep Aboriginal people out of the region and on to the Tasman Peninsula. The campaign failed and was abandoned seven weeks later, but by then Tasmania's Aboriginal population had fallen to about 300.[54]

Removal of Aboriginal people

After hostilities between settlers and Aboriginal peoples ceased in 1832, almost all of the remnants of the Indigenous population were persuaded by government agent George Augustus Robinson to move to Flinders Island. Many quickly succumbed to infectious diseases to which they had no immunity, reducing the population further.[55][56] Of those removed from Tasmania, the last to die was Truganini, in 1876.

The near-destruction of Tasmania's Aboriginal population has been described as an act of genocide by historians including Robert Hughes, James Boyce, Lyndall Ryan and Tom Lawson.[36][57][58] However, other historians including Henry Reynolds, Richard Broome and Nicholas Clements do not agree with the genocide thesis, arguing that the colonial authorities did not intend to destroy the Aboriginal population in whole or in part.[59][60] Boyce has claimed that the April 1828 "Proclamation Separating the Aborigines from the White Inhabitants" sanctioned force against Aboriginal people "for no other reason than that they were Aboriginal".[61] However, as Reynolds, Broome and Clements point out, there was open warfare at the time.[59][60] Boyce described the decision to remove all Tasmanian Aboriginal people after 1832—by which time they had given up their fight against white colonists—as an extreme policy position. He concluded: "The colonial government from 1832 to 1838 ethnically cleansed the western half of Van Diemen's Land."[61] Nevertheless, Clements and Flood note that there was another wave of violence in north-west Tasmania in 1841, involving attacks on settlers' huts by a band of Aboriginal Tasmanians who had not been removed from the island.[62][63]

Proclamation as a colony

Van Diemen's Land—which thus far had existed as a territory within the colony of New South Wales—was proclaimed a separate colony, with its own judicial establishment and Legislative Council, on 3 December 1825. Transportation to the island ceased in 1853 and the colony was renamed Tasmania in 1856, partly to differentiate the burgeoning society of free settlers from the island's convict past.[64]

The Legislative Council of Van Diemen's Land drafted a new constitution which gained Royal Assent in 1855. The Privy Council also approved the colony changing its name from "Van Diemen's Land" to "Tasmania", and in 1856 the newly elected bicameral parliament sat for the first time, establishing Tasmania as a self-governing colony of the British Empire.[65]

The colony suffered from economic fluctuations, but for the most part was prosperous, experiencing steady growth. With few external threats and strong trade links with the Empire, Tasmania enjoyed many fruitful periods in the late 19th century, becoming a world-centre of shipbuilding. It raised a local defence force that eventually played a significant role in the Second Boer War in South Africa, and Tasmanian soldiers in that conflict won the first two Victoria Crosses awarded to Australians.

Federation

In 1901, the Colony of Tasmania united with the five other Australian colonies to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Tasmanians voted in favour of federation with the largest majority of all the Australian colonies.

20th and 21st century

Tasmania was an early adopter of electric street lighting. Australia's first electric street lights were switched on in Waratah in 1886.[66] Launceston became the first completely electrified city on the island in 1885, followed closely by the township of Zeehan in 1900.

The state economy was riding mining prosperity until World War I. In 1901, the state population was 172,475.[67] The 1910 foundation of what would become Hydro Tasmania began to shape urban patterns, as well as future major damming programs.[68] Hydro's influence culminated in the 1970s when the state government announced plans to flood environmentally significant Lake Pedder. As a result of the eventual flooding of Lake Pedder, the world's first green party was established; the United Tasmania Group.[69] National and international attention surrounded the campaign against the Franklin Dam in the early 1980s.[70]

Tasmanian Enid Lyons became the first female member of the House of Representatives at the 1943 federal election and first female to serve in the federal cabinet. In May 1948, Margaret McIntyre achieved another milestone as the first female elected to the Parliament of Tasmania. Less than six months after her election, McIntyre died in the crash of the Lutana near Quirindi on 2 September 1948.

After the end of World War II, the state saw major urbanisation, and the growth of towns like Ulverstone.[68] It gained a reputation as "Sanitorium of the South" and a health-focused tourist boom began to grow. The MS Princess of Tasmania began her maiden voyage in 1959, the first car ferry to Tasmania.[68] As part of the boom, Tasmania allowed the opening of the first casino in Australia in 1968.[68] Queen Elizabeth II visited the state in 1954, and the 50s and 60s were charactered by the opening of major public services, including the Tasmanian Housing Department and Metro Tasmania public bus services. A jail was opened at Risdon in 1960, and the State Library of Tasmania the same year. The University of Tasmania also moved to its present location in 1963.

The state was badly affected by the 1967 Tasmanian fires, killing 64 people and destroying over 652,000 acres in five hours.[71] In 1975 the Tasman Bridge collapsed when the bridge was struck by the bulk ore carrier Lake Illawarra. It was the only bridge in Hobart, and made crossing the Derwent River by road at the city impossible. The nearest bridge was approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) to the north, at Bridgewater.

Throughout the 1980s, strong environmental concerns saw the building of the Australian Antarctic Division headquarters, and the proclamation of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. The Franklin Dam was blocked by the federal government in 1983, and CSIRO opened its marine studies centre in Hobart. Pope John Paul II would hold mass at Elwick Racecourse in 1986.

The 1990s were characterised by the fight for LGBT rights in Tasmania, culminating in the intervention of the United Nations Human Rights Committee in 1997 and the decriminalization of homosexuality that year.[72] Christine Milne became the first female leader of a Tasmanian political party in 1993, and major council amalgamations reduce the number of councils from 46 to 29.

Following the Port Arthur massacre on 28 April 1996, which resulted in the loss of 35 lives and injured 21 others, the Australian Government conducted a review of its firearms policies and enacted new nationwide gun ownership laws under the National Firearms Agreement.

In 2000, Queen Elizabeth II once again visited the state. Gunns rose to prominence as a major forestry company during this decade, only to collapse in 2013. In 2004, Premier Jim Bacon died in office from lung cancer. In January 2011 philanthropist David Walsh opened the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart to international acclaim. Within 12 months, MONA became Tasmania's top tourism attraction.[73]

The COVID-19 pandemic in Tasmania resulted in at least 230 cases and 13 deaths as of September 2021[update].[74] In 2020, after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic (SARS-CoV-2) and its spread to Australia, the Tasmanian government issued a public health emergency on 17 March,[75] the following month receiving the state's most significant outbreak from the North-West which required assistance from the Federal government. In late 2021, Tasmania was leading the nationwide vaccination response.[76]

Geography

This article or section may need to be cleaned up or summarized because it has been split from/to Geography of Tasmania. |

Tasmania, the largest island of Australia, has a landmass of 68,401 km2 (26,410 sq mi) and is located directly in the pathway of the notorious "Roaring Forties" wind that encircles the globe. To its north, it is separated from mainland Australia by Bass Strait. Tasmania is the only Australian state that is not located on the Australian mainland. About 2,500 kilometres (1,300 nautical miles) south of Tasmania island lies the George V Coast of Antarctica. Depending on which borders of the oceans are used, the island can be said to be either surrounded by the Southern Ocean, or to have the Pacific on its east and the Indian to its west. Still other definitions of the ocean boundaries would have Tasmania with the Great Australian Bight to the west, and the Tasman Sea to the east. The southernmost point on mainland Tasmania is approximately 43°38′37″S 146°49′38″E / 43.64361°S 146.82722°E at South East Cape, and the northernmost point on mainland Tasmania is approximately 40°38′26″S 144°43′33″E / 40.64056°S 144.72583°E in Woolnorth / Temdudheker near Cape Grim / Kennaook. Tasmania lies at similar latitudes to Te Waipounamu / South Island of New Zealand and parts of Patagonia in South America. Areas at equivalent latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere include Hokkaido in Japan, Northeast China (Manchuria), Central Italy, and United States cities such as New York and Chicago.

The most mountainous region is the Central Highlands area, which covers most of the central western parts of the state. The Midlands located in the central east, is fairly flat, and is predominantly used for agriculture, although farming activity is scattered throughout the state. Tasmania's tallest mountain is Mount Ossa at 1,617 m (5,305 ft).[77] Much of Tasmania is still densely forested, with the Southwest National Park and neighbouring areas holding some of the last temperate rain forests in the Southern Hemisphere. The Tarkine, containing Savage River National Park located in the island's far north west, is the largest temperate rainforest area in Australia covering about 3,800 square kilometres (1,500 sq mi).[78] With its rugged topography, Tasmania has a great number of rivers. Several of Tasmania's largest rivers have been dammed at some point to provide hydroelectricity. Many rivers begin in the Central Highlands and flow out to the coast. Tasmania's major population centres are mainly situated around estuaries (some of which are named rivers).

Tasmania is in the shape of a downward-facing triangle, likened to a shield, heart, or face. It consists of the main island as well as at least a thousand neighbouring islands within the state's jurisdiction. The largest of these are Flinders Island in the Furneaux Group of Bass Strait, King Island in the west of Bass Strait, Cape Barren Island south of Flinders Island, Bruny Island separated from Tasmania by the D'Entrecasteaux Channel, Macquarie Island 1,500 km from Tasmania, and Maria Island off the east coast. Tasmania features a number of separated and continuous mountain ranges. The majority of the state is defined by a significant dolerite exposure, though the western half of the state is older and more rugged, featuring buttongrass plains, temperate rainforests, and quartzite ranges, notably Federation Peak and Frenchmans Cap. The presence of these mountain ranges is a primary factor in the rain shadow effect, where the western half receives the majority of rainfall, which also influences the types of vegetation that can grow. The Central Highlands feature a large plateau which forms a number of ranges and escarpments on its north side, tapering off along the south, and radiating into the highest mountain ranges in the west. At the north-west of this, another plateau radiates into a system of hills where takayna / Tarkine is located.

The Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) divides Tasmania into 9 bioregions:[79] Ben Lomond, Furneaux, King, Central Highlands, Northern Midlands, Northern Slopes, Southern Ranges, South East, and West.

Tasmania's environment consistes of many different biomes or communities across its different regions. It is the most forested state in Australia, and preserves the country's largest areas of temperate rainforest. A distinctive type of moorland found across the west, and particularly south-west of Tasmania, are buttongrass plains, which are speculated to have been expanded by Tasmanian Aboriginal burning practices.[80] Tasmania also features a diverse alpine garden environment, such as cushion plant. Highland areas receive consistent snowfall above ~1,000 metres every year, and due to cold air from Antarctica, this level often reaches 800 m, and more occasionally 600 or 400 metres. Every five or so years, snow can form at sea level.[81] This environment gives rise to the cypress forests of the Central Plateau and mountainous highlands. In particular, the Walls of Jerusalem with large areas of rare pencil pine, and its closest relative King Billy pine. On the West Coast Range and partially on Mount Field, Australia's only winter-deciduous plant, deciduous beech is found, which forms a carpet or krummholz, or very rarely a 4-metre tree.[82]

Tasmania features a high concentration of waterfalls. These can be found in small creeks, alpine streams, rapid rivers, or off precipitous plunges. Some of the tallest waterfalls are found on mountain massifs, sometimes at a 200-metre cascade. The most famous and most visited waterfall in Tasmania is Russell Falls in Mount Field due to its proximity to Hobart and stepped falls at a total height of 58 metres.[83] Tasmania also has a large number of beaches, the longest of which is Ocean Beach on the West Coast at about 40 kilometres.[84] Wineglass Bay in Freycinet on the east coast is a well-known landmark of the state.

The Tasmanian temperate rainforests cover a few different types. These are also considered distinct from the more common wet sclerophyll forests, though these eucalypt forests often form with rainforest understorey and ferns (such as tree-ferns) are usually never absent. Rainforest found in deep gullies are usually difficult to traverse due to dense understorey growth, such as from horizontal (Anodopetalum biglandulosum). Higher-elevation forests (~500 to 800 m) have smaller ground vegetation and are thus easier to walk in. The most common rainforests usually have a 50-metre[85] canopy and are varied by environmental factors. Emergent growth usually comes from eucalyptus, which can tower another 50 metres higher (usually less), providing the most common choice of nesting for giant wedge-tailed eagles.

The human environment ranges from urban or industrial development to farming or grazing land. The most cultivated area is the Midlands, where it has suitable soil but is also the driest part of the state.

Tasmania's insularity was possibly detected by Captain Abel Tasman when he charted Tasmania's coast in 1642. On 5 December, Tasman was following the east coast northward to see how far it went. When the land veered to the north-west at Eddystone Point,[86] he tried to keep in with it but his ships were suddenly hit by the Roaring Forties howling through Bass Strait.[87] Tasman was on a mission to find the Southern Continent, not more islands, so he abruptly turned away to the east and continued his continent-hunting.[88]

The next European to enter the strait was Captain James Cook on HMS Endeavour in April 1770. However, after sailing for two hours westward into the strait against the wind, he turned back east and noted in his journal that he was "doubtful whether they [i.e. Van Diemen's Land and New Holland] are one land or no".[89]

The strait was named after George Bass, after he and Matthew Flinders passed through it while circumnavigating Van Diemen's Land in the Norfolk in 1798–99. At Flinders' recommendation, the Governor of New South Wales, John Hunter, in 1800 named the stretch of water between the mainland and Van Diemen's Land "Bass's Straits".[90] Later it became known as Bass Strait.

The existence of the strait had been suggested in 1797 by the master of Sydney Cove when he reached Sydney after deliberately grounding his foundering ship and being stranded on Preservation Island (at the eastern end of the strait). He reported that the strong south westerly swell and the tides and currents suggested that the island was in a channel linking the Pacific and southern Indian Ocean. Governor Hunter thus wrote to Joseph Banks in August 1797 that it seemed certain a strait existed.[91]

Climate

Tasmania has a relatively cool temperate climate compared to the rest of Australia, spared from the hot summers of the mainland and experiencing four distinct seasons.[92] Summer is from December to February when the average maximum sea temperature is 21 °C (70 °F) and inland areas around Launceston reach 24 °C (75 °F). Other inland areas are much cooler, with Liawenee, located on the Central Plateau, one of the coldest places in Australia, ranging between 4 and 17 °C (39 and 63 °F) in February. Autumn is from March to May, with mostly settled weather, as summer patterns gradually take on the shape of winter patterns.[93] The winter months are from June to August and are generally the wettest and coldest months in the state, with most high lying areas receiving considerable snowfall. Winter maximums are 12 °C (54 °F) on average along coastal areas and 3 °C (37 °F) on the central plateau, as a result of a series of cold fronts from the Southern Ocean. Inland areas receive regular freezes throughout the winter months. Spring is from September to November, and is an unsettled season of transition, where winter weather patterns begin to take the shape of summer patterns, although snowfall is still common up until October. Spring is generally the windiest time of the year with afternoon sea breezes starting to take effect on the coast.

| City/town | Mean min. temp °C | Mean max. temp °C | No. clear days | Rainfall (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hobart | 8.3 | 16.9 | 41 | 616[94] |

| Launceston | 7.0 | 18.3 | 50 | 666[95] |

| Devonport | 8.0 | 16.8 | 61 | 778[96] |

| Strahan | 7.9 | 16.5 | 41 | 1,458[97] |

| Climate data for Hobart (Battery Point) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 41.8 (107.2) |

40.1 (104.2) |

39.1 (102.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.6 (94.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.6 (105.1) |

41.8 (107.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.7 (72.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.3 (32.5) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 43.7 (1.72) |

37.8 (1.49) |

37.0 (1.46) |

42.6 (1.68) |

39.2 (1.54) |

46.0 (1.81) |

44.5 (1.75) |

63.0 (2.48) |

55.6 (2.19) |

52.8 (2.08) |

50.7 (2.00) |

53.0 (2.09) |

565.9 (22.28) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 9.5 | 9.1 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 14.1 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 15.0 | 13.5 | 11.7 | 150.7 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 51 | 52 | 52 | 56 | 58 | 64 | 61 | 56 | 53 | 51 | 53 | 49 | 55 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 257.3 | 226.0 | 210.8 | 177.0 | 148.8 | 132.0 | 151.9 | 179.8 | 195.0 | 232.5 | 234.0 | 248.0 | 2,393.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 59 | 62 | 57 | 59 | 53 | 49 | 53 | 58 | 59 | 58 | 56 | 53 | 56 |

| Source 1: Bureau of Meteorology (1991–2020 averages;[98] extremes 1882–present)[99][100][101] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Bureau of Meteorology, Hobart Airport (sunshine hours)[102] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Launceston (Ti Tree Bend) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 39.0 (102.2) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.0 (91.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

33.8 (92.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.8 (60.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

3.4 (38.1) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−3 (27) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 51.5 (2.03) |

35.2 (1.39) |

38.8 (1.53) |

51.0 (2.01) |

63.1 (2.48) |

66.9 (2.63) |

78.3 (3.08) |

83.8 (3.30) |

65.5 (2.58) |

48.0 (1.89) |

52.9 (2.08) |

45.8 (1.80) |

680.8 (26.80) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 87.1 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 48 | 49 | 48 | 56 | 63 | 69 | 69 | 63 | 59 | 54 | 52 | 49 | 57 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 285.2 | 256.9 | 241.8 | 198.0 | 155.0 | 135.0 | 142.6 | 170.5 | 201.0 | 254.2 | 267.0 | 282.1 | 2,589.3 |

| Source 1: Bureau of Meteorology (1991–2020 averages;[103] extremes 1980–present)[104] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Bureau of Meteorology, Launceston Airport (1981–2004 sunshine hours)[105] | |||||||||||||

Biodiversity

Geographically and biological isolated, Tasmania is known for its unique endemic flora and fauna.

Flora

Tasmania has extremely diverse vegetation, from the heavily grazed grassland of the dry Midlands to the tall evergreen eucalypt forest, alpine heathlands and large areas of cool temperate rainforests and moorlands in the rest of the state. Many species are unique to Tasmania, and some are related to species in South America and New Zealand through ancestors which grew on the supercontinent of Gondwana, 50 million years ago. Nothofagus gunnii, commonly known as Australian beech, is Australia's only temperate native deciduous tree and is found exclusively in Tasmania.[106]

Distinctive species of plant in Tasmania include:

- Eucalyptus regnans (mountain ash) – the tallest flowering plant and hardwood in the world, reaching 100 m (328 ft).[107]

- Nothofagus cunninghamii (myrtle beech) – the most abundant temperate rainforest canopy species found in Tasmania.

- Nothofagus gunnii (deciduous beech) – Australia's only winter-deciduous tree.

- Atherosperma moschatum (blackheart sassafras) – a co-dominant rainforest tree with a nutmeg aroma.

- Lagarostrobos franklinii (Huon pine) – one of the oldest-lived tree species, and a self-preserving timber.

- Phyllocladus aspleniifolius (celery-top pine) – a celery-leaved conifer found in rainforests.

- Athrotaxis (Tasmanian cedar/redwood) – a genus comprising three extant species related to sequoia found in Tasmania.[108]

- Eucryphia lucida (leatherwood) – a prominent floral symbol of Tasmania and a unique monofloral honey species.[109]

Bush tucker

Tasmania also has a number of native edibles, known as bush tucker in Australia. These plants were foraged by the Tasmanian Aboriginals and also used for other purposes, such as construction. Unusual trees such as cider gum (Eucalyptus gunnii) had their manna used to make a syrup or an alcohol (cider). Other trees such as wattles (acacias) like blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon) and mimosa (Acacia dealbata) could have their seeds eaten or crushed into a powder. There are also many berries such as snowberry (Gaultheria hispida), fruits such as heartberry (Aristotelia peduncularis), and vegetables such as river mint (Mentha australis), though no crops like maize that are used for large production.[110]

Fauna

Tasmania has a large percentage of endemism whilst featuring many types of animals found on mainland Australia. Many of these species, such as the platypus, are larger than their mainland relatives.[111] The island of Tasmania was home to the thylacine, a marsupial which resembled a fossa or some say a wild dog. Known colloquially as the Tasmanian tiger for the distinctive striping across its back, it became extinct in mainland Australia much earlier because of competition by the dingo, introduced in prehistoric times. Owing to persecution by farmers, government-funded bounty hunters and, in the final years, collectors for overseas museums, it appears to have been exterminated in Tasmania. The Tasmanian devil became the largest carnivorous marsupial in the world following the extinction of the thylacine in 1936 and is now found in the wild only in Tasmania. Tasmania was one of the last regions of Australia to be introduced to domesticated dogs. Dogs were brought from Britain in 1803 for hunting kangaroos and emus. This introduction completely transformed Aboriginal society, as it helped them to successfully compete with European hunters and was more important than the introduction of guns for the Aboriginal people.[112]

Tasmania is a hotspot for giant habitat trees and the large animal species that occupy them, notably the endangered Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax fleayi), the Tasmanian masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae castanops), the Tasmanian giant freshwater crayfish (Astacopsis gouldi), the yellow wattlebird (Anthochaera paradoxa), the green rosella (Platycercus caledonicus) and others. Tasmania is also home to the world's only three migratory parrots, the critically endangered Orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster), the Blue-winged parrot (Neophema chrysostoma), and the fastest parrot in the world, the swift parrot (Lathamus discolor).[113] Tasmania has 12 endemic species of bird in total.[114]

Mycology

Tasmania is a hotspot for fungal diversity. The importance of fungi in Tasmania's ecology is often overlooked; nonetheless, they play a vital role in the natural vegetation cycle.[115]

Conservation

Like the rest of Australia, Tasmania suffers from an endangered species problem. In particular, many important Tasmanian subspecies and world-significant species of animal are classified as at risk in some way. A famous example is the Tasmanian devil, which is endangered due to devil facial tumour disease. Some species have already gone extinct, primarily due to human interference, such as in the case of the thylacine or the Tasmanian emu.[116][117] In Tasmania, there are about 90 endangered, vulnerable, or threatened vertebrate species classified by the state or Commonwealth governments.[118] Because of a reliance on roads and private vehicle transport, and a high concentration of animal populations divided by this development, Tasmania has the worst (per kilometre) roadkill rate in the world, with 32 animals killed per hour and at least 300,000 per year.[119]

Protected areas of Tasmania cover 21% of the island's land area in the form of national parks.[120] The Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) was inscribed by UNESCO in 1982, where it is globally significant because "most UNESCO World Heritage sites meet only one or two of the ten criteria for that status. The Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) meets 7 out of 10 criteria. Only one other place on earth—China’s Mount Taishan—meets that many criteria".[121] Controversy surrounds the decision in 2014 by the Abbott federal Liberal government to request the area's delisting and opening for resource exploration (before it was rejected by the UN Committee at Doha),[122] and the current mining and deforestation in the state's Tarkine region, the largest single temperate rainforest in Australia.[123][124]

Demography

The population of Tasmania is the most homogeneous of any Australian state, being mostly of British (primarily English) descent.[125]

Until 2012, Tasmania was the only state in Australia with an above-replacement total fertility rate; Tasmanian women had an average of 2.24 children each.[126] By 2012 the birth rate had slipped to 2.1 children per woman, bringing the state to the replacement threshold, but it continues to have the second-highest birth rate of any state or territory (behind the Northern Territory).[127]

Major population centres include Hobart, Launceston, Devonport, Burnie, and Ulverstone. Kingston is often defined as a separate city but is generally regarded as part of the Greater Hobart Area.[128]

| Cities and towns by population[129] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Settlement | Population | Metro population |

|||

| 1 | Hobart[130] | 178,009 | 252,669 | |||

| 2 | Launceston | 68,813 | 110,472 | |||

| 3 | Devonport-Latrobe | 30,297 | ||||

| 4 | Burnie-Somerset | 19,385 | ||||

| 5 | Ulverstone | 14,490 | ||||

| 6 | Sorell-Dodges Ferry | 14,400 | ||||

| 7 | Kingston | 10,409 | ||||

| 8 | George Town | 7,117 | ||||

| 9 | Wynyard | 5,990 | ||||

| 10 | New Norfolk | 5,834 | ||||

| 11 | Smithton | 3,881 | ||||

| 12 | Penguin | 3,849 | ||||

| Name | Population |

|---|---|

| Greater Hobart | 226,884[17] |

| Launceston | 86,404[131] |

| Devonport | 30,044[131] |

| Burnie | 26,978[131] |

| Ulverstone | 14,424[131] |

Ancestry and immigration

| Birthplace[N 1] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 440,818 |

| England | 19,283 |

| Mainland China | 6,830 |

| Nepal | 6,219 |

| India | 6,137 |

| New Zealand | 5,483 |

| Philippines | 2,441 |

| Scotland | 2,280 |

| Netherlands | 2,136 |

| South Africa | 2,089 |

| Germany | 2,087 |

| United States | 2,056 |

At the 2016 census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[N 2][132][133]

19.3% of the population was born overseas at the 2016 census. The five largest groups of overseas-born were from England (3.7%), New Zealand (1%), Mainland China (0.6%), Scotland (0.4%) and the Netherlands (0.4%).[132][133]

4.6% of the population, or 23,572 people, identified as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) in 2016.[N 5][132][133]

Language

At the 2021 census, 86.1% of inhabitants spoke only English at home, with the next most common languages being Mandarin (1.5%), Nepali (1.3%), Punjabi (0.5%) and Spanish (0.3%).[135]

Religion

Religious Affiliation (2021)

In 2021, 50.0% of people in Tasmania reported having no religious affiliation, a substantial increase from 38.2% in 2016 and just 5.1% in 1971. Meanwhile, Christianity remained the largest religious affiliation in the state, with 38.4% identifying as Christian, though this proportion has steadily declined over time—from 88.7% in 1971 to 49.7% in 2016.[135]

Non-Christian religions accounted for 4.5% of the population in 2021, with Hinduism (1.7%), Buddhism (1.0%), and Islam (0.9%) being the most prevalent among them.[135][132][133]

Government

The form of the government of Tasmania is prescribed in its constitution, which dates from 1934. Since 1901, Tasmania has been a state of the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Australian Constitution regulates its relationship with the Commonwealth and prescribes which powers each level of government is allowed.

Tasmania is represented in the Senate by 12 senators, on an equal basis with all other states. In the House of Representatives, Tasmania is entitled to five seats, which is the minimum allocation for a state guaranteed by the Constitution—the number of House of Representatives seats for each state is otherwise decided on the basis of their relative populations, and Tasmania has never qualified for five seats on that basis alone. Tasmania's House of Assembly use a system of multi-seat proportional representation known as Hare-Clark.

Parliamentary elections

At the 2002 state election, the Labor Party won 14 of the 25 House seats. The people decreased their vote for the Liberal Party; representation in the Parliament fell to seven seats. The Greens won four seats, with over 18% of the popular vote, the highest proportion of any Green party in any parliament in the world at that time.

| Composition of the Parliament of Tasmania | ||

|---|---|---|

| Political Party |

House of Assembly |

Legislative Council |

| ALP | 10 | 3 |

| Liberal | 14 | 4 |

| Greens | 5 | 1 |

| Lambie Network | 1 | — |

| Independent | 5 | 7 |

| Source: Tasmanian Electoral Commission | ||

On 23 February 2004 the Premier Jim Bacon announced his retirement, after being diagnosed with lung cancer. In his last months he opened a vigorous anti-smoking campaign which included many restrictions on where individuals could smoke, such as pubs. He died four months later. Bacon was succeeded by Paul Lennon, who, after leading the state for two years, went on to win the 2006 state election in his own right. Lennon resigned in 2008 and was succeeded by David Bartlett, who formed a coalition government with the Greens after the 2010 state election resulted in a hung parliament. Bartlett resigned as Premier in January 2011 and was replaced by Lara Giddings, who became Tasmania's first female Premier. In March 2014 Will Hodgman's Liberal Party won government, ending sixteen years of Labor governance, and ending an eight-year period for Hodgman himself as Leader of the Opposition.[136] Hodgman then won a second term of government in the 2018 state election, but resigned mid-term in January 2020 and was replaced by Peter Gutwein.[137]

In May 2021, the Tasmanian state election was held after being called early by the incumbent Liberal Party, resulting in their return to government and establishment of a one-seat majority. It was also the first time that the Liberal Party had been elected three-times in a row.[138]

In April 2022, former deputy premier Jeremy Rockliff became Premier after Gutwein announced his retirement from politics.[139]

Politics

Tasmania has a number of undeveloped regions. Proposals for local economic development have been faced with requirements for environmental sensitivity, or opposition. In particular, proposals for hydroelectric power generation were debated in the late 20th century. In the 1970s, opposition to the construction of the Lake Pedder reservoir impoundment led to the formation of the world's first Green party, the United Tasmania Group.[140]

In the early 1980s the state debated the proposed Franklin River Dam. The anti-dam sentiment was shared by many Australians outside Tasmania and proved a factor in the election of the Hawke Labor government in 1983, which halted construction of the dam.[141] Since the 1980s the environmental focus has shifted to old growth logging and mining in the Tarkine region, which have both proved divisive.[142] The Tasmania Together process recommended an end to clear felling in high conservation old growth forests by January 2003, but was unsuccessful.

In 1996, the House of Assembly consisted of 35 seats with 7 seats per each of the five electorates. By the 1998 election, the number of seats had been reduced down to 25, or 5 per each electorate. This resulted in the reduction of the Greens' number of seats from 4 to 1, and increased the proportion of seats held by both the Labor and Liberal parties.[143] This was despite growth in population (five-fold since responsible government) and an increase in the voting percentage required for a majority government. There was also no public consultation, and inquiries at the time had recommended the opposite. The House of Assembly Select Committee in 2020 recommended in its report that the number should be increased again from 25 to 35, arguing that such a small representation would undermine democracy and limit the capabilities of the government. In 2010, the major party leadership had even endorsed reinstating the 35 seat number, but Liberal and Labor support was withdrawn the following year, with only the Greens keeping their commitment.[144]

Local government

Tasmania has 29 local government areas. Local councils are responsible for functions delegated by the Tasmanian parliament, such as urban planning, road infrastructure and waste management. Council revenue comes mostly from property taxes and government grants.

As with the House of Assembly, Tasmania's local government elections use a system of multi-seat proportional representation known as Hare–Clark. Local government elections take place every four years and are conducted by the Tasmanian Electoral Commission by full postal ballot. The next local government elections will be held during October 2026.[145]

Economy

Traditionally, Tasmania's main industries have been mining (including copper, zinc, tin, and iron), agriculture, forestry, and tourism. Tasmania is on Australia's electrical grid and in the 1940s and 1950s, a hydro-industrialisation initiative was embodied in the state by Hydro Tasmania. These all have had varying fortunes over the last century and more, involved in ebbs and flows of population moving in and away dependent upon the specific requirements of the dominant industries of the time.[146] The state also has a large number of food exporting sectors, including but not limited to seafood (such as salmon, abalone and crayfish).

In the 1960s and 1970s there was a decline in traditional crops such as apples and pears,[147] with other crops and industries eventually rising in their place. During the 15 years until 2010, new agricultural products such as wine, saffron, pyrethrum and cherries have been fostered by the Tasmanian Institute of Agricultural Research.

Favourable economic conditions throughout Australia, cheaper air fares, and two new Spirit of Tasmania ferries have all contributed to what is now a rising tourism industry.

About 1.7% of the Tasmanian population are employed by local government.[148] Other major employers include Nyrstar, Norske Skog, Grange Resources, Rio Tinto,[149] the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hobart, and Federal Group. Small business is a large part of the community life, including Incat, Moorilla Estate and Tassal. In the late 1990s, a number of national companies based their call centres in the state after obtaining cheap access to broad-band fibre optic connections.[150][146]

34% of Tasmanians are reliant on welfare payments as their primary source of income.[151] This number is in part due to the large number of older residents and retirees in Tasmania receiving Age Pensions. Due to its natural environment and clean air, Tasmania is a common retirement selection for Australians.[152]

| Industry | AU$ (billions) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Construction | 7.989 | 13.7 |

| Manufacturing | 7.421 | 12.7 |

| Health care & social assistance | 6.303 | 10.8 |

| Agriculture | 5.115 | 8.7 |

| Public administration & safety | 3.572 | 6.1 |

| Transport, postal, & warehousing | 3.269 | 5.6 |

| Financial & insurance services | 3.030 | 5.2 |

| Education & training | 2.794 | 4.8 |

| Electricity, gas, water, & waste services | 2.637 | 4.5 |

| Retail trade | 2.552 | 4.4 |

| Information media & telecommunications | 2.246 | 3.8 |

| Professional, scientific, & technical services | 2.033 | 3.5 |

| Mining | 1.875 | 3.2 |

| Wholesale trade | 1.687 | 2.9 |

| Accommodation & food services | 1.586 | 2.7 |

| Other services | 1.360 | 2.3 |

| Rental, hiring, & real estate services | 1.117 | 1.9 |

| Administrative & support services | 1.045 | 1.8 |

| Arts & recreation services | 0.893 | 1.5 |

| Total industries | $58.523 | 100% |

| Industry | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Health care & social assistance | 36,631 | 14.6 |

| Retail trade | 26,290 | 10.5 |

| Education & training | 23,272 | 9.3 |

| Construction | 20,688 | 8.3 |

| Public administration & safety | 20,137 | 8.0 |

| Manufacturing | 18,897 | 7.5 |

| Accommodation & food services | 18,554 | 7.4 |

| Agriculture | 15,021 | 6.0 |

| Professional, scientific, & technical services | 14,097 | 5.6 |

| Transport, postal, & warehousing | 10,691 | 4.3 |

| Other services | 8,739 | 3.5 |

| Administrative & support services | 6,535 | 2.6 |

| Wholesale trade | 6,185 | 2.5 |

| Arts & recreation services | 5,992 | 2.4 |

| Financial & insurance services | 5,248 | 2.1 |

| Electricity, gas, water, & waste services | 4,321 | 1.7 |

| Information media & telecommunications | 3,552 | 1.4 |

| Rental, hiring, & real estate services | 2,990 | 1.2 |

| Mining | 2,780 | 1.1 |

| Total industries | 250,621 | 100% |

Science and technology

The modern scientific sector in Tasmania benefits from around $500 million in annual investment.[155] Tasmania has a long history of scientific and technological innovation.[156] The first scientific-style observations were conducted by the First Nation Tasmanians, primarily through the watching and mythologising of the night sky. Their story explaining the phases of the moon and sun "is one of the rare accounts that explicitly acknowledges that the light of the Moon is a reflection of the Sun's light".[157]

The French D'Entrecasteaux Expedition of 1792–93 had anchored twice during its search of the missing La Pérouse in the Baie de la Recherche (Recherche Bay) in far-south Tasmania. During their stay, the crew took botanical, astronomical, and geomagnetic observations which were the first of their kind performed on Australian soil. As well as this, they engaged in amicable relations with the locals and environment, gifting the area a "French garden", in which "the relatively extensive, well-documented (both pictorially and written) encounters [...] between [them] provided a very early opportunity for meetings and mutual observation".[158]

The longest-running branch of the Royal Society outside of the United Kingdom is the Royal Society of Tasmania which was summoned in 1843. The Tasmanian Society of Natural History had been formed previously in 1838 before its merger with the Royal Society in 1849. It had been served by early botanists working in Tasmania such as Ronald Gunn and his correspondences.[159][160]

Although Tamworth in New South Wales is often credited[161] as being the first place in Australia with electric street lighting in 1888, Waratah in North West Tasmania was actually the first place to do so in Australia in 1886, although at a smaller scale.[162]

Culture

Literature

Notable titles by Tasmanian authors include The Museum of Modern Love[163][164] by Heather Rose, The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan, The Alphabet of Light and Dark by Danielle Wood, The Roving Party by Rohan Wilson and The Year of Living Dangerously by Christopher Koch, The Rain Queen[165] by Katherine Scholes, Bridget Crack[166] by Rachel Leary, and The Blue Day Book by Bradley Trevor Greive. A small part of Helen Garner's Monkey Grip is set in Hobart as the main characters take a sojourn there. Children's books include They Found a Cave by Nan Chauncy, The Museum of Thieves by Lian Tanner, Finding Serendipity, A Week Without Tuesday and Blueberry Pancakes Forever[167] by Angelica Banks, Tiger Tale by Marion and Steve Isham. Tasmania is home to the eminent literary magazine that was formed in 1979, Island magazine, and the biennial Tasmanian Writers and Readers Festival, now renamed the Hobart Writers Festival.

Tasmanian Gothic is a literary genre which expresses the island state's "peculiar 'otherness' in relation to the mainland, as a remote, mysterious and self-enclosed place."[168] Marcus Clarke's novel For the Term of his Natural Life, written in the 1870s and set in convict era Tasmania, is a seminal example. This distinctive Gothic is not just restricted to literature, but can be represented through all the arts, such as in painting, music, or architecture.

Visual arts

The biennial Tasmanian Living Artists' Week is a ten-day statewide festival for Tasmania's visual artists. The fourth festival in 2007 involved more than 1000 artists. Tasmania is home to two winners of the prestigious Archibald Prize—Jack Carington Smith in 1963 for a portrait of James McAuley, and Geoffrey Dyer in 2003 for his portrait of Richard Flanagan. Photographers Olegas Truchanas and Peter Dombrovskis are known for works that became iconic in the Lake Pedder and Franklin Dam conservation movements. English-born painter John Glover (1767–1849) is known for his paintings of Tasmanian landscapes, and is the namesake for the annual Glover Prize, which is awarded to the best landscape painting of Tasmania. The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) opened in January 2011 at the Moorilla Estate in Berriedale,[169] and is the largest privately owned museum complex in Australia.[170]

Music and performing arts

Tasmania has a varied musical scene, ranging from the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra whose home is the Federation Concert Hall, to a substantial number of small bands, orchestras, string quintets, saxophone ensembles and individual artists who perform at a variety of venues around the state. Tasmania is also home to a vibrant community of composers including Constantine Koukias, Maria Grenfell and Don Kay. Tasmania is also home to one of Australia's leading new music institutions, IHOS Music Theatre and Opera and gospel choirs, the Southern Gospel Choir. Prominent Australian metal bands Psycroptic and Striborg hail from Tasmania.[171] Noir-rock band The Paradise Motel and 1980s power-pop band The Innocents[172] are also citizens.

The Tasmanian Aboriginals were known to have sung oral traditions, as Fanny Cochrane Smith (the last fluent speaker of any Tasmanian language) had done so in recordings from 1899 to 1903.[173][174] Tasmania has been home to some early and prominent Australian composers. In piano, Kitty Parker from Longford was described by world-famous Australian composer Percy Grainger as his most gifted student.[175] Peter Sculthorpe was originally from Launceston and became well known in Australia for his works which were influenced by his Tasmanian origins, and he is, by coincidence, distantly related to Fanny Cochrane Smith.[176] In 1996, Sculthorpe composed the piece Port Arthur: In Memoriam for chamber orchestra, which was first performed by the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra.[177] Charles Sandys Packer was an early Tasmanian example of the tradition of Australian classical music, transported for the crime of embezzlement in 1839, and at a similar time Francis Hartwell Henslowe had spent time as a public servant in Tasmania. Amy Sherwin, known as the Tasmanian Nightingale was a successful soprano,[178] and Eileen Joyce, who came from remote Zeehan, became a world-renowned pianist at the time of her peak.[179]

Cinema

Films set in Tasmania include Young Einstein, The Tale of Ruby Rose, The Hunter, The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce, Arctic Blast, Manganinnie (with music composed by Peter Sculthorpe), Van Diemen's Land, Lion, and The Nightingale. Common within Australian cinema, the Tasmanian landscape is a focal point in most of their feature film productions. The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce and Van Diemen's Land are both set during an episode of Tasmania's convict history. Tasmanian film production goes as far back as the silent era, with the epic For The Term of His Natural Life in 1927 being the most expensive feature film made on Australian shores. The Kettering Incident, filmed in and around Kettering, Tasmania, won the 2016 AACTA Award for Best Telefeature or Miniseries. The documentary series Walking with Dinosaurs was partly filmed in Tasmania due to its terrain.

The Tasmanian Film Corporation, which financed Manganinnie, was the successor to the Tasmanian Government Department of Film Production but disappeared after privatisation. Its role is now filled by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Screen Tasmania, and private ventures such as Blue Rocket Productions.

Higher Education

Tasmania is served by the University of Tasmania, a research university established in 1846.

Media

Tasmania has five broadcast television stations which produce local content including ABC Tasmania, Seven Tasmania – an affiliate of the Seven Network, WIN Television Tasmania – an affiliate of the Nine Network, 10 Tasmania – an affiliate of Network 10 (joint owned by WIN and Southern Cross), and SBS.

Sport

Sport is an important pastime in Tasmania, and the state has produced several famous sportsmen and women and also hosted several major sporting events. The Tasmanian Tigers cricket team represents the state successfully (for example the Sheffield Shield in 2007, 2011 and 2013) and plays its home games at the Bellerive Oval in Hobart, which is also the home ground for the Hobart Hurricanes in the Big Bash League. In addition, Bellerive Oval regularly hosts international cricket matches. Famous Tasmanian cricketers include David Boon, former Australian captains Ricky Ponting and Tim Paine.

Australian rules football in Tasmania is the most watched form of football and a Tasmanian team was awarded a license to enter the Australian Football League (AFL) in 2028 to be based out of a new Macquarie Point Stadium. AFL matches have been played since 2001 at Aurora Stadium in Launceston and Bellerive Oval in Hobart. Local leagues include the North West Football League and Tasmanian State League.

Soccer in Tasmania is the most participated football code and there is an active Tasmanian A-League bid. The existing statewide league is the NPL Tasmania.

Rugby Union is also played in Tasmania and is governed by the Tasmanian Rugby Union. Ten clubs take part in the statewide Tasmanian Rugby Competition.

Tasmania hosts the professional Moorilla International tennis tournament as part of the lead up to the Australian Open and is played at the Hobart International Tennis Centre, Hobart.

The Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race is an annual event starting in Sydney, NSW, on Boxing Day and finishing in Hobart, Tasmania. It is widely considered to be one of the most difficult yacht races in the world.[180]

In basketball, Tasmania has previously been represented in the National Basketball League (NBL) by Launceston Casino City (1980–1982), the Devonport Warriors (1983–1984), and the Hobart Devils (1983–1996). Since the 2021–22 NBL season, Tasmania has been represented by the Tasmania JackJumpers, a state-wide franchise which plays its home games in both Hobart and Launceston. The JackJumpers secured their maiden NBL championship in the 2023–24 season, marking Tasmania's first NBL title since Launceston Casino City in 1981.[181]

Cuisine

Tasmanian Aboriginal people had a diverse diet, including native currants, pigface, and native plums, and a wide range of birds and kangaroos. Seafood has always been a significant part of the Tasmanian diet, including its wide range of shellfish, which are still commercially farmed[182] such as crayfish, orange roughy, salmon[182] and oysters.[182] Seal meat also formed a significant part of the Aboriginal diet.[183]

Tasmania's non-Aboriginal cuisine has a unique history to mainland Australia. It has developed through many subsequent waves of immigration. Tasmanian traditional foods include scallop pies – a pie filled with scallops in curry – and curry powder, which was popularised by Keen's Curry in the 19th century.[184] Tasmania also produces and consumes wasabi, saffron, truffles and leatherwood honey.[185]

Tasmania now has a wide range of restaurants, in part due to the arrival of immigrants and changing cultural patterns. Scattered across Tasmania are many vineyards,[182] and Tasmanian beer brands such as Boags and Cascade are known and sold in Mainland Australia. King Island off the northwestern coast of Tasmania has a reputation for boutique cheeses[182] and dairy products.

The Central Cookery Book was written in 1930 by A. C. Irvine and is still popular in Australia and even internationally.[186][187] Tasmanian cuisine is often unique and has won many awards. One example is the Hartshorn Distillery, which has won prizes in the World Vodka Awards for three years in a row since 2017.[188]

Events

To foster tourism, the state government encourages or supports several annual events in and around the island. The best known of these is the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, starting on Boxing Day in Sydney and usually arriving at Constitution Dock in Hobart around three to four days later, during the Taste of Tasmania, an annual food and wine festival. Other events include the Targa Tasmania rally which attracts rally drivers from around the world and is staged all over the state, over five days. Rural or regional events include Agfest, a three-day agricultural show held at Carrick (just west of Launceston) in early May and NASA supported TastroFest – Tasmania's Astronomy Festival, held early August in Ulverstone (Northwest Tasmania). The Royal Hobart Show and Royal Launceston Show are both held in October annually.

Music events held in Tasmania include the Falls Festival at Marion Bay (a Victorian event now held in both Victoria and Tasmania on New Year's Eve); the Festival of Voices, a national celebration of song held each year in Hobart attracting international and national teachers and choirs in the heart of Winter; and MS Fest, a charity music event held in Launceston to raise money for those with multiple sclerosis. The Cygnet Folk Festival is one of Australia's most iconic folk music festivals and is held in Cygnet in the Huon Valley every year in January.[189] The Tasmanian Lute Festival is an early music event held in different locations in Tasmania every two years. Recent additions to the state arts events calendar include the 10 Days on the Island arts festival, MONA FOMA, run by David Walsh and curated by Brian Ritchie and Dark Mofo also run by David Walsh and curated by Leigh Carmichael.

The Unconformity is a three-day festival held every two years in Queenstown on the West Coast.[190][191] Each February in Evandale a penny-farthing championships are held.[192]

Perception within Australia

Tasmania is perceived within Australia and internationally as an island with pristine wildlife, water and air. It is known for its ecotourism for these reasons, and is considered an idyllic location for Australians considering a "tree-" or "sea-change", or are seeking retirement because of Tasmania's temperate environment and friendly locals.[193] In other parts of the world, Tasmania is considered as the opposite side of the planet to most places, and supposedly home to mythically exotic animals, such as the Tasmanian Devil as popularised by Warner Brothers.

Stereotypes

Tasmania has a reputation within Australia that is often at odds with the reality of the state or may have only been true during colonial times and has only persevered on the Australian mainland as a myth. Because of these stereotypes, Tasmania is often referred to as the primary target (i.e., "butt") of mainland Australian jokes.[194] In more recent times, references to insults against Tasmania are more sarcastic and jovial, but angst against the island still exists. The most commonly cited sarcastic comment is on the supposedly 'two-headed' Tasmanians, which originated due to some colonists developing goitres from the low amount of iodine in the island's soil.[195] But as Tasmania receives higher volumes of inter-state tourists, the perceptions are in the process of changing.[196]

The most prominent example of negative stereotype is of inbreeding due to the relatively small size of Tasmania compared to the rest of Australia (though Tasmania is nearly as large as the Republic of Ireland in area, and more populous than Iceland). This is untrue and if it had once been the case, it would have existed in the rest of colonial Australia as well, though Tasmania's penal establishments were some of the harshest in the entire colony and home to infamous bushrangers. This is a part of the also-receding global stereotype that all Australians are or were derived from criminals, even as most convicts were transported for petty crimes. During this period of European settlement, Tasmania was the second centre of power (and a significant port of the British Empire) on the continent after New South Wales, before being surpassed in the latter half of the 19th century by Victoria and regions sustained by mining booms following the cessation of transportation in 1853.[197] A mentality developed in certain corners of Australia, and led to a general dislike of Tasmania amongst these people, even if the opinion-holder had never properly visited. It can rise to such an extent as to argue for the secession of Tasmania from the rest of Australia, in an effort to 'recover' Australia's reputation from Tasmania.[198]

Transport

Air

Tasmania's main air carriers are Jetstar and Virgin Australia; Qantas and QantasLink. These airlines fly direct routes to Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney. Major airports include Hobart Airport and Launceston Airport; the smaller airports, Burnie (Wynyard) and King Island, serviced by Rex Airlines; and Devonport, serviced by QantasLink; have services to Melbourne. Intra-Tasmanian air services are offered by Airlines of Tasmania. Until 2001 Ansett Australia operated majorly out of Tasmania to 12 destinations nationwide. Tourism-related air travel is also represented in Tasmania, such as in the Par Avion route between Cambridge Aerodrome near Hobart to Melaleuca in Southwest National Park.

Antarctica base

Tasmania – Hobart in particular – serves as Australia's chief sea link to Antarctica, with the Australian Antarctic Division located in Kingston. Hobart is also the home port of the French ship l'Astrolabe, which makes regular supply runs to the French Southern Territories near and in Antarctica.

Road

Within the state, the primary form of transport is by road. Since the 1980s, many of the state's highways have undergone regular upgrades. These include the Hobart Southern Outlet, Launceston Southern Outlet, Bass Highway reconstruction, and the Huon Highway. Public transport is provided by Metro Tasmania bus services, regular taxis and Hobart only[199] UBER ride-share services within urban areas, with Redline Coaches, Tassielink Transit and Callows Coaches providing bus service between population centres.

Rail

Rail transport in Tasmania consists of narrow-gauge lines to all four major population centres and to mining and forestry operations on the west coast and in the northwest. Services are operated by TasRail. Regular passenger train services in the state ceased in 1977; the only scheduled trains are for freight, but there are tourist trains in specific areas, for example the West Coast Wilderness Railway. There is an ongoing proposal to reinstate commuter trains to Hobart. This idea however lacks political motivation.

Shipping

There is a substantial amount of commercial and recreational shipping within Hobart's harbour, and the port hosts approximately 120 cruise ships during the warmer half of the year, and there are occasional visits from military vessels.[200]

Burnie and Devonport on the northwest coast host ports and several other coastal towns host either small fishing ports or substantial marinas. The domestic sea route between Tasmania and the mainland is serviced by Bass Strait passenger/vehicle ferries operated by the Tasmanian government-owned Spirit of Tasmania. The state is also home to Incat, a manufacturer of very high-speed aluminium catamarans that regularly broke records when they were first launched.

Gallery

-

Granton Vineyard in autumn

-

92-metre-high Eucalyptus regnans

-

Cradle Mountain from the shore of Dove Lake

-

Sub-Antarctic Garden, Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens, Hobart

See also

- Index of Australia-related articles

- List of amphibians of Tasmania

- List of schools in Tasmania

- Omission of Tasmania from maps of Australia

- Outline of Australia

- Regions of Tasmania

Notes

- ^ In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, England, Scotland, Mainland China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau are listed separately

- ^ As a percentage of 475,884 persons who nominated their ancestry at the 2016 census.

- ^ The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the Anglo-Celtic group.[134]

- ^ Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

- ^ Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

References