Hujum

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic female dress |

|---|

| Types |

| Practice and law by country |

| Concepts |

| Other |

Hujum (Russian: Худжум Khudžum [xʊd͡ʐʐʊm]; Arabic: هجوم, transl. 'onslaught') refers to a broad campaign undertaken by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to remove all manifestations of gender inequality within the Union Republics of Central Asia. Beginning in the Stalinist era, it particularly targeted prevalent practices among Muslims, such as female seclusion from society, female veiling practices and the practice of inheriting women as property after the death of their husbands.[1] While it was often symbolized by the burning of the veils that Muslim women wore, the removal of veiling practices was not the campaign's sole goal. The Party began re-emphasizing their message of women's liberation within class consciousness. By abolishing Central Asian societal norms and heralding in women's liberation, the Soviets believed they could clear the way for the construction of socialism. The campaign's purpose was to rapidly change the lives of women in Muslim societies so that they would be able to actively participate in public life, formal employment, education, and ultimately membership in the Communist Party. It was originally conceived to enforce laws that gave equality to women in patriarchal societies by creating literacy programs and bringing women into the workforce.

The campaign was initiated on International Women's Day; 8 March 1927. It was a change from the earlier policies that were in place under the Bolsheviks, who prioritized unrestricted religious freedom for Central Asians.[2] In contrast to how it was presented to the populace, Hujum was seen by Muslims as a campaign through which outsiders (i.e., Slavs) sought to force their cultural values onto the indigenous Turkic populations. Thus, the veil inadvertently became a marker of cultural identity;[2] wearing it became an act of pro-Islamic political defiance as well as a sign of support for ethnic nationalism.[2] However, over time, the campaign was a success: the rate of female literacy increased, while polygamy, honour killings, child marriages, and veiling diminished. Paranjas were rare by the 1950s in Soviet Central Asia and the same happened in Afghanistan by the 1960s (although they became popular again in Afghanistan after the fall of the communist secular government in the 1980s and the rise of Islamists).[3][4]

Pre-Soviet traditions

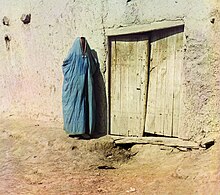

[edit]Veiling in Central Asia was intricately related to class, ethnicity, and religious practice. Prior to Soviet rule, Nomadic Kazakh, Kirgiz, and Turkmen women used a yashmak, a veil that covered only the mouth.[5] The yashmak was applied in the presence of elders and was rooted in Mediterranean and West Asian customs (see namus).

Tatars emigrating from Russia were unveiled.[6] Though Muslim, they had been under Russian rule since the 16th century and were in many ways people of the middle and upper classes. Only settled Uzbeks,Tajiks and people of Caucasus had strict veiling practices, which Tamerlane and Mongols supposedly initiated.[7] Even among this population, veiling depended on social class and location. Urban women veiled with chachvon (face veil) and paranja (body veil), although the cost of the veil prevented poorer women from using it.[8] Rural Uzbeks, meanwhile, wore a chopan, a long robe that could be pulled up to cover the mouth in the presence of men.[9]

Traditional culture

[edit]

Pre-Soviet Central Asian culture and religion promoted female seclusion. Cultural mores strongly condemned unveiling as it was thought to lead to premarital or adulterous sex, a deep threat to Central Asian conceptions of family honor.[10] Many mullahs also considered the full body veil Islamic, and strongly protested any attempts to alter it. Female seclusion in homes was encouraged for the same reasons although home seclusion was far more oppressive. Female quarters and male quarters existed separately, and women were not allowed in the presence of male non-relatives.[11] Women from rich families were the most isolated as the family could afford to build numerous rooms and hire servants, removing the need for leaving the home. The traditional settled society encouraged seclusion as a way to protect family honor, as religiously necessary, and as a way of asserting male superiority over women.

The Jadids

[edit]

Arrayed against the traditional practices stood the Jadids, elite Central Asians whose support for women's education would help spur Soviet era unveiling. Jadids were drawn primarily from the upper ranks of settled Uzbeks, the class in which veiling and seclusion were most prevalent. Very few were interested in banning the veil.[12] However, Jadid nationalism did promote education for women, believing that only educated women could raise strong children.[13] The Jadid's female relatives received good educations and would go on to form the core of Soviet-era feminism. The elite nature of the movement, however, restricted the education initiative to the upper class. Despite the Jadid's limited reach and modest goals, the mullahs criticized the Jadids harshly.[14] Mullahs believed that education would lead to unveiling and subsequent immorality, an opinion most non-Jadids shared. The Jadids prepared the ground for women's rights in the Soviet era, but accomplished little outside their own circle.

Tsarist rule

[edit]Starting in the 1860s, the Tsarist conquest of Central Asia both increased the number who veiled and raised the status of veiling. Russia ruled Central Asia as one unit called "Turkestan", although certain zones retained domestic rule.[15] The Tsarist government, while critical of veiling, kept separate laws for Russians and Central Asians in order to facilitate a peaceful, financially lucrative empire.[16] Separate laws allowed prostitution in Russian zones, encouraging veiling as a firm way for Central Asian women to preserve their honor.[17] Russian conquest also brought wealth and, subsequently, more hajj participation. Hajj participation sparked a rise in religious observance, and in public displays of piety via the veil. Tsarist control thus primarily served to indirectly increase the veil's use.

Russian control shifted Central Asian's attitude toward the veil by encouraging Tatar immigration. Tatars had spent centuries under Russian rule and had adopted many European customs, including forgoing the veil. As Turkic speaking Muslims, they also had a unique engagement with Central Asian life.[18] Faced with this synthesis of Islamic and western practice, Central Asian women began to question, if not outright attack, veiling. By opening up Central Asian society to Tatar immigration, Russians enabled the spread of ideas that conflicted with traditional Central Asian mores.

Soviet pre-Hujum policies

[edit]

Although the communist revolution promised to redefine gender, Soviet rule until 1924 did little to alter women's status in Central Asia. From 1918 to 1922 Soviet troops fought against revived Khanates, basmachi rebels, and Tsarist armies.[19] During this time Tsarist Turkestan was renamed the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (TASSR).[20] Initial central control was so weak that Jadids, acting under the communist banner, provided the administrative and ruling class.[21] The Jadid's legislated against polygamy, Sharia, and bride price, but did not enforce these rulings. Veiling remained unaddressed.[22] Moscow did not press the case; it was more interested in reviving war-ravaged Central Asia than altering cultural norms. Earlier, Soviet pro-nationality policies encouraged veil wearing as a sign of ethnic difference between Turkmen and Uzbeks.[23]

This era also saw the mullahs gradually split over women's rights.[24] Many continued to decry the USSR's liberal rulings, while others saw women's rights as necessary towards staying relevant. While Soviets were ideologically interested in Women's Rights, local instability prevented bold policies or implementation.

1924 ushered in a limited campaign against the veil. In accordance with the Soviet pro-nationality policy, the TASSR was split into five republics: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.[25] The Soviets also took this time to purge the Jadids from government, either through execution or exile.[26] Soviet rule encouraged the founding of the anti-veiling Women's Division, or Zhenotdel. Few married women joined as their immediate community strongly condemned unveiling. Consequently, its workers were usually Jadid educated women or widows.

State policy, operating through the Women's Division encouraged unveiling through private initiative rather than state driven mass unveilings. Stories written by activist authors encouraged unveiling and emphasized that women were not morally degraded by the decision to unveil. These stories targeted widows and impoverished women, as they had the least to lose by unveiling. Despite the Division's attempts, few women choose to unveil. The few who did unveil usually had Jadid or communist families. While some women unveiled during trips to Russia, many re-veiled upon returning to Central Asia.

Still, the chachvon and paranji aided women's rights by calling attention to disparities between male and female power. Compared to the chachvon and paranji, nomadic women's yashmak veiled comparatively little and was applied only in the presence of elders. Soviet authorities took this as evidence of women's freedom and praised the nomad's gender norms.[27] Women's rights, though, were still curtailed in nomadic culture. Women were not given the right to divorce, had fewer inheritance rights, and were generally under the sway of male decisions. While the Women's Division attempted to use the yashmak as a rallying call for women's rights, its low symbolic appeal relative to the chachvon stymied change. The post-Jadid, more explicitly communist government encouraged women's activism but ultimately was not strong enough to enact widespread change, either in settled or nomadic communities.

Soviet motivations

[edit]The hujum was part of a larger goal to "create a cohesive Soviet population in which all citizens would receive the same education, absorb the same ideology, and identify with the Soviet state as a whole."[28]

The Zhenotdel, mostly composed of women hailing from Russian and other Slavic areas, believed that such a campaign would be welcomed and adopted by the Muslim women in Central Asia. Throwing off the veil in public (an individual act of emancipation) was expected to correspond with (or catalyze) a leap upward in women's political consciousness and a complete transformation in her cultural outlook.[29]

Launching the campaign

[edit]In 1927 Tashkent, Uzbekistan became the center of the campaign for women's liberation. The campaigns aimed to completely and swiftly eradicate the veils (paranji) that Muslim women wore in the presence of unrelated males.

The brunt of the campaign fell on the shoulders of the Slavic women of the Zhenotdel, who wished to complete the campaign in six months (allowing them to celebrate their success alongside the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution in October 1927). The hujum campaign was officially launched in Uzbekistan on International Women's Day (March 8, 1927).

Mechanics of the Hujum in Uzbekistan

[edit]To eradicate the intended target (that is, the paranji), the Zhenotdel workers designated their time to organizing public demonstrations on a grand scale, where fiery speeches and inspirational tales would speak for women's liberation. If all went according to plan, Uzbek women would cast off their paranjis en masse.

Usually, efforts to transform women were scheduled to follow or even accompany collectivization in most regions. By aligning collectivization with the hujum, the idea was that the Soviets could more easily control and intervene in the everyday life of the Uzbeks.[30] In the beginning stages the hujum was not applied universally. Instead, only Communist Party members and their immediate families were required to participate in the campaign. The idea was that only after this portion of the campaign demonstrated the change in these families would it be spread to non-Communists, like trade-union members, factory workers, and schoolteachers.

Specifics of the campaign

[edit]"К наступлению!"(K nastupleniiu!) what means "To the Attack!" became the slogan associated with the hujum campaign.[31] The Zhenotdel supplemented this assault with additional women's liberation institutions, which included the construction of women's clubs, the re-stocking of women's-only stores, and the fight against illiteracy among women.

In order to guarantee their hegemony over the indigenous population, Soviet authorities used direct physical force and coercion, along with laws and legal norms as a means to control the local populations and to propagate unveiling. Most women unveiled because they succumbed to the Party's coercive methods. The majority of women did not choose to unveil, they were either given orders directly from a government representative, or their husbands (under government pressure) told them to.[32]

Uzbek reactions

[edit]The hujum met with resilience and resistance from the Uzbek population. Uzbeks outside the party ignored new laws, or subverted them in various ways. They utilized the weapons of the weak: protests, speeches, public meetings, petitions against the government, or a simple refusal to practice the laws.

Some welcomed the campaign, but these supporters often faced unrelenting insults, threats of violence, and other forms of harassment that made life especially difficult. Thus many Uzbek men and women who may have sympathized with the hujum campaign kept a low profile and opted out of the campaign altogether. Those brave enough to partake in the unveiling campaign were often ostracized, attacked, or even killed for their failure to defend tradition and Muslim law (shariah). The Uzbek clergy encouraged Uzbek men to attack unveiled women, and about 2,500 unveiled women were reportedly murdered by men.[33]

The Soviet attack on female veiling and seclusion proved to pin Party activists in direct confrontation with Islamic clergy, who vehemently opposed the campaign, some going so far as to advocate threats and attacks on unveiled women.

Every attack on the veil only proved to foment further resistance through the proliferation of the wearing of the veil among the Uzbeks.[34] While Muslim cultural practices, such as female seclusion and the wearing of the paranji, were attacked by this campaign, they emerged from the hujum still deeply entrenched in Uzbek culture and society. Uzbek Communists were first and foremost loyal to their Uzbek Muslim culture and society.

The fundamental problem of the hujum was that women were trapped between the Soviet state and their own society, with little agency to make their own decisions. In the male-dominated society of Uzbekistan, men often went to great lengths to prevent their wives from attending Soviet meetings and demonstrations. Fearing of the public opinions of their mahallas, many women decided against unveiling. The mahalla's judgment could be unmerciful. In Uzbekistan, there was little to no middle ground. If women resisted state pressure, they complied with social pressure, or vice versa.[35] Women often sided with their husbands in their reaction to the hujum: they would follow their husband's instructions.

Murder proved an effective method of terrorizing women into re-veiling. It also served to remind women where they stood in the social hierarchy. These murders were not spontaneous eruptions, but premeditated attacks designed to demonstrate that the local community held more authority over women's actions than did the state. Infamous premeditated murders of women that unveiled included those of Nukhon Yuldasheva[36] and Tursunoy Saidazimova.[37][38]

An unveiling campaign was also carried out in the predominantly Shia Muslim Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. The unveiling campaign in Azerbaijan was supported by the outreach efforts of the Ali Bayramov Club women's organization.[39] The unveiling campaign in Azerbaijan is commemorated by the Statue of a Liberated Woman, showing a woman unveiling, which was erected in Baku in 1960.

Outcomes

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

There was fierce debate surrounding the idea of making veiling illegal, but it was eventually abandoned. It was believed that Soviet law could not advance without the support of the local populations. However, with the proliferation of murders linked to unveiling, new laws were introduced in 1928 and 1929 that addressed women's personal safety. These laws, deeming attacks on unveiling as "counterrevolutionary" and as "terrorist acts" (meriting the death penalty),[40] were designed to help local authorities defend women from harassment and violence.

In the private domestic domain, women's roles changed little, however their roles in the public domain as well as material conditions changed drastically, because of the hujum. The hujum's multifaceted approach to social and cultural reform in the form of women's liberation transformed women in public, breaking seclusion and creating new and active members of society. The concepts of women's abilities were transformed, but little progress was made in challenging gender ideals and roles.[41]

Decades after the hujum was first launched, the paranji was eventually phased out nearly completely, and mature women took to wearing large, loose scarves to cover their heads instead of paranjis. As a result of Soviet initiatives, literacy rates in Uzbekistan in the 1950s reached 70 to 75 percent. Employment for women rose rapidly in the 1930s due to the hujum. Women worked in the fields of the collective farms. By the late 1950s, women outnumbered men in the collective farms. Modernization's effects were clear in Uzbekistan: education was made available for most Uzbek regions, literacy rose, and health care was vastly improved.

See also

[edit]- Women in Islam

- Feminism

- Niqāb

- Honor killing

- Violence against women

- Nurkhon Yuldasheva

- Tursunoi Saidazimova

- Tadzhikhan Shadieva

- Tamara Khanum

- Hamza Hakimzade Niyazi

- Yodgor Nasriddinova

- Kashf-e hijab

- Gruaja Shqiptare and the unveiling in Albania

- Ali Bayramov Club and the unveiling in Azerbaijan

- Huda Sha'arawi and the Egyptian unveiling of the 1920s.

- Latife Uşaki and the Turkish unveiling of the 1920s.

- Soraya Tarzi and the Afghan unveiling of the 1920s.

- Humaira Begum and the Afghan unveiling of the 1950s.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Northrop (2001a), p. 115.

- ^ a b c The Bolsheviks and Islam, International Socialism – Issue: 110

- ^ Abdullaev, Kamoludin (2018-08-10). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7.

- ^ Ubiria, Grigol (2015). Soviet Nation-Building in Central Asia: The Making of the Kazakh and Uzbek Nations. Routledge. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-1-317-50435-1.

- ^ Edgar (2003), p. 137.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 35.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 136

- ^ Khalid (1998), p. 222.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 132.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 50.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 29.

- ^ Khalid (1998), p. 228.

- ^ Khalid (1998), p. 225.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 42.

- ^ Massell (1974), p. 18.

- ^ Sahadeo (2007), p. 158.

- ^ Kamp (2006), pp. 135–136.

- ^ Kamp (2006), pp. 35–36.

- ^ Massell (1974), p. 14.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 61.

- ^ Khalid (1998), p. 288.

- ^ Kamp (2006), pp. 68–69.

- ^ Massell (1974), p. 46.

- ^ Keller (1998), pp. 33–34.

- ^ Kamp (2006), pp. 106–121.

- ^ Khalid (1998), p. 300.

- ^ Edgar (2003), p. 149.

- ^ Edgar (2006)

- ^ Northrop (2001b), p. 132.

- ^ Kamp (2006)

- ^ Northrop (2001b), p. 131.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 176.

- ^ Sevgi Adak: Anti-Veiling Campaigns in Turkey: State, Society and Gender in the Early ..., p. 162

- ^ Northrop (2001b)

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 13.

- ^ Rubin, Don; Pong, Chua Soo; Chaturvedi, Ravi; Majundar, Ramendu; Tanokura, Minoru (2001). The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Asia/Pacific. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415260879.

- ^ Massell, Gregory J. (2015-03-08). The Surrogate Proletariat: Moslem Women and Revolutionary Strategies in Soviet Central Asia, 1919-1929. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400870295.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 186.

- ^ Heyat, F. 2002. Azeri women in transition. London: Routledge. 89-94.

- ^ Northrop (2001a), p. 119.

- ^ Kamp (2006), p. 215.

References

[edit]- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2003). "Emancipation of the unveiled: Turkmen women under Soviet rule, 1924–1929". Russian Review. 62 (1): 132–149. doi:10.1111/1467-9434.00267. JSTOR 3664562.

- Edgar, Adrienne (2006). "Bolshevism, patriarchy, and the nation: the Soviet "emancipation" of Muslim women in pan-Islamic perspective" (PDF). Slavic Review. 65 (2): 252–272. doi:10.2307/4148592. JSTOR 4148592. S2CID 164160742. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25.

- Kamp, Marianne (2006). The New Woman in Uzbekistan: Islam, Modernity and Unveiling Under Communism. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98644-9.

- Keller, Shoshana (1998). "Trapped between State and Society: Women's Liberation and Islam in Soviet Uzbekistan, 1926–1941". Journal of Women's History. 10 (1): 20–44. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0552. S2CID 143436623.

- Khalid, Adeeb (1998). The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform: Jadidism in Central Asia. Comparative studies on Muslim societies. Vol. 27. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21356-2.

- Massell, Gregory J. (1974). The Surrogate Proletariat: Moslem Women and Revolutionary Strategies in Soviet Central Asia, 1919-1929. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-7837-9384-9.

- Northrop, Douglas (2001a). "Subaltern dialogues: subversion and resistance in Soviet Uzbek family law". Slavic Review. 60 (1): 115–139. doi:10.2307/2697646. JSTOR 2697646. S2CID 147540996.

- Northrop, Douglas T. (2001b). "Hujum: unveiling campaigns and local responses in Uzbekistan, 1927". In Donald J. Raleigh (ed.). Provincial Landscapes: Local Dimensions of Soviet Power, 1917–1953. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 125–145. ISBN 978-0-8229-6158-1.

- Sahadeo, Jeff (2007). "Progress or peril: migrants and locals in Russian Tashkent, 1906–14". In Nicholas B. Breyfogle, Abby M. Schrader & Willard Sunderland (ed.). Peopling the Russian Periphery: Borderlans Colonization in Eurasian History. London: Routledge. pp. 148–165. ISBN 978-0-415-41880-5.

- Soviet Central Asia

- Islamic female clothing

- Islam in the Soviet Union

- Feminism in the Soviet Union

- Anti-religious campaign in the Soviet Union

- Persecution by atheist states

- Persecution of Muslims

- Religious persecution by communists

- Anti-Islam sentiment in the Soviet Union

- Women's rights in the Soviet Union

- Discrimination in Uzbekistan

- Hijab