Lu Xun

Lu Xun | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

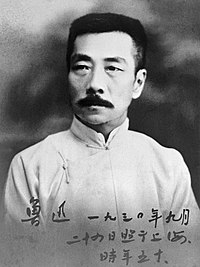

Lu in 1930 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Zhou Zhangshou 25 September 1881 Shaoxing, Zhejiang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 19 October 1936 (aged 55) Shanghai, Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Tomb of Lu Xun, Shanghai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Genres | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subjects | Critique of traditional Confucian values and thought | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literary movement | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years active | 1902–1936 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Employers |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable works |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Zhu An | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Partner | Xu Guangping (1927–1936) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 魯迅 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 鲁迅 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Birth name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 周樹人 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 周树人 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New Culture Movement |

|---|

|

|

Lu Xun (Chinese: 鲁迅; pinyin: Lǔ Xùn, [lù ɕŷn]; 25 September 1881 – 19 October 1936), born Zhou Zhangshou, was a Chinese writer, literary critic, lecturer, and state servant. He was a leading figure of modern Chinese literature. Writing in vernacular and Literary Chinese, he was a short story writer, editor, translator, literary critic, essayist, poet, and designer. In the 1930s, he became the titular head of the League of Left-Wing Writers in Shanghai during republican-era China (1912–1949).

Lu Xun was born into a family of landlords and government officials in Shaoxing, Zhejiang; the family's financial resources declined over the course of his youth. Lu aspired to take the imperial examinations, but due to his family's relative poverty he was forced to attend government-funded schools teaching "foreign education". Upon graduation, Lu studied medicine at Tohoku University in Japan, but later dropped out. He became interested in studying literature but was eventually forced to return to China because of his family's lack of funds. After returning to China, Lu worked for several years teaching at local secondary schools and colleges before finally finding an office at the Republic of China Ministry of Education.

Following the May Fourth Movement in 1919, Lu's writing began to exert a substantial influence on Chinese literature and popular culture. Like many of the movement's leaders, Lu was a leftist. After the proclamation of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, his work received considerable acclaim from the Chinese government, with Mao Zedong being an admirer of Lu's writing throughout his life. Though he was sympathetic to socialist ideas, Lu never joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Lu Xun was born in Shaoxing, Zhejiang. As was common before the 20th century, Lu used several names. His birth name was "Zhou Zhangshou" (Chinese: 周樟壽). His courtesy name was "Yushan" (豫山), which he later changed to "Yucai" (豫才). In 1898, before he went to the Jiangnan Naval Academy, he took the given name "Shuren" (樹人), which figuratively means "to be an educated man".[1] The name "Lu Xun", by which he is most well known internationally, was a pen name chosen upon the initial publishing of his story "Diary of a Madman" in 1918.[2]

By the time Lu Xun was born, the Zhou family had been prosperous for centuries, and had become wealthy through landowning, pawnbroking, and by having several family members promoted to government positions. His paternal grandfather, Zhou Fuqing, was appointed to the Imperial Hanlin Academy in Beijing, the highest position possible for aspiring civil servants at that time.

Zhou's mother was a member of the same landed gentry class as Lu Xun's father, from a slightly smaller town in the countryside (Anqiaotou, Zhejiang; a part of Tongxiang). Because formal education was not considered socially appropriate for girls,[citation needed] she had not received any education, but she still taught herself how to read and write. The surname Lu (魯) was the same as his mother's.[3]

Lu's early education was based on the Confucian classics, in which he studied poetry, history, and philosophy—subjects which, he later reflected, were neither useful nor interesting to him. Instead, he enjoyed folk stories and opera, including the mythological narratives of the Classic of Mountains and Seas and the ghost stories told to him by a servant when he was a child.[4]

By the time Lu was born, his family's prosperity had already been declining. His father, Zhou Boyi, had been successful at passing the county-level imperial examinations, the route to wealth and social success in imperial China, but was unsuccessful in writing the more competitive provincial-level examinations (the juren exam). In 1893 Zhou Boyi was discovered attempting to bribe an examination official. Lu Xun's grandfather was implicated, and was arrested and sentenced to beheading for his son's crime. The sentence was later commuted, and he was imprisoned in Hangzhou instead.

After the affair, Zhou Boyi was stripped of his position in the government and forbidden to ever again write the civil service examinations.[4] The Zhou family only prevented Lu's grandfather from being executed through regular, expensive bribes to authorities, until he was finally released in 1901.[5]

After the family's attempt at bribery was discovered, Zhou Boyi engaged in heavy drinking and opium use and his health declined. Local Chinese doctors attempted to cure him through a series of expensive quack prescriptions, including monogamous crickets, sugar cane that had survived frost three times, ink, and the skin from a drum. Despite these expensive treatments, Zhou Boyi died of an asthma attack in 1896, at the age of 35.[5] He might have suffered from dropsy.[4]

Education

[edit]Lu Xun half-heartedly participated in the first, district-level civil service examination in 1898,[6] but then abandoned pursuing a traditional Confucian education or career.[5] He intended to study at a prestigious school, the "Seeking Affirmation Academy", in Hangzhou, but was forced by his family's poverty to instead study at the "Jiangnan Naval Academy", a tuition-free military school in Nanjing.[7]

As a consequence of Lu's decision to attend a military school specializing in Western education, his mother wept, he was instructed to change his name to avoid disgracing his family,[5] and some of his relatives began to look down on him. Lu attended the Jiangnan Naval Academy for half a year, and left after it became clear that he would be assigned to work in an engine room, below deck, which he considered degrading.[7] He later wrote that he was dissatisfied with the quality of teaching at the academy.[8]

After leaving the school, Lu sat for the lowest level of the civil service exams, and finished 137th of 500. He intended to sit for the next-highest level, but became upset when one of his younger brothers died, and abandoned his plans.[7]

Lu Xun transferred to another government-funded school, the "School of Mines and Railways", and graduated from that school in 1902. The school was Lu's first exposure to foreign literature, philosophy, history, and science, and he studied English and German intensively. Some of the influential authors that he read during that period include T. H. Huxley, John Stuart Mill, Yan Fu, and Liang Qichao. His later social philosophy may have been influenced by several novels about social conflict that he read during the period, including Ivanhoe and Uncle Tom's Cabin.[7]

He did very well at the school with relatively little effort, and occasionally experienced racism directed at him from resident Manchu bannermen. The racism he experienced may have influenced his later sense of Han Chinese nationalism.[7] After graduating Lu Xun planned to become a foreign doctor.[8]

In 1902, Lu Xun left for Japan on a Qing government scholarship to pursue an education in foreign medicine. After arriving in Japan he attended the Kobun Institute, a preparatory language school for Chinese students attending Japanese universities. After encouragement from a classmate, he cut off his queue that Han Chinese were obliged to wear at the time, and practiced jujutsu in his free time. He had an ambiguous attitude towards Chinese revolutionary politics during the period, and it is not clear whether he joined any of the revolutionary parties that were popular among Chinese expatriates in Japan at that time, such as the Tongmenghui. He experienced anti-Chinese racism, but was simultaneously disgusted with the behaviour of some Chinese who were living in Japan. His earliest surviving essays, written in Literary Chinese, were published while he was attending this school, and he published his first Chinese translations of famous and influential foreign novels, including Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas.[9]

In 1904, Lu began studying at the Sendai Medical Academy in northern Honshu, but remained there for less than two years. He generally found his studies at the school tedious and difficult, partially due to his imperfect Japanese. While studying in Sendai he befriended one of his professors, Fujino Genkurō, who helped him prepare class notes. Because of their friendship Lu was accused by his classmates of receiving special assistance from Fujino.[9] Lu later recalled his mentor affectionately in the essay "Mr Fujino", published in Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk. The essay has since become one of his most widely renowned works, and is read in the Chinese middle school curriculum. Fujino later reciprocated Lu's respect in an obituary written for Lu after his death in 1937.

While Lu Xun was attending medical school, the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) broke out.[10]: 37 Part of the war was fought on disputed Chinese land. Lantern slides used in the classroom also featured news items.[10]: 37 One news slide showed a public execution of a Chinese prisoner being executed by the Japanese military for being an alleged Russian spy.[10]: 37 The on-lookers shown in the slide were mainly Chinese, and Lu was shocked by what he viewed as their complete apathy.[10]: 37 In his preface to Nahan, the first collection of his short stories, Lu explained how viewing this scene influenced him to quit studying Western medicine, and to become a literary physician to what he perceived to be China's spiritual problems instead:[8]

At the time, I hadn't seen any of my fellow Chinese in a long time, but one day some of them showed up in a slide. One, with his hands tied behind him, was in the middle of the picture; the others were gathered around him. Physically, they were as strong and healthy as anyone could ask, but their expressions revealed all too clearly that spiritually they were calloused and numb. According to the caption, the Chinese whose hands were bound had been spying on the Japanese military for the Russians. He was about to be decapitated as a 'public example.' The other Chinese gathered around him had come to enjoy the spectacle.[9]

In March 1906, Lu Xun abruptly and secretly terminated his pursuit of the degree and left college. At the time he told no one. After arriving in Tokyo he made sure that the Chinese embassy would not cancel his scholarship and registered at the local German Institute, but was not required to take classes there. He began to read Nietzsche, and wrote a number of essays in the period that were influenced by his philosophy.[9]

In June 1906, Lu's mother heard a rumor that he had married a Japanese girl and had a child with her, and feigned illness as a pretext to ask Lu to return home, where she would then force him to take part in an arranged marriage she had agreed to several years before.[11] The girl, Zhu An, had little in common with Lu, was illiterate, and had been subject to foot binding.[12] Lu Xun married her, but they never had a romantic relationship. Despite that fact, Lu took care of her material needs for the rest of his life.[9] Several days after the ceremony Lu sailed back to Japan with his younger brother, Zuoren, and left behind his new wife.[9]

After returning to Japan he took informal classes in literature and history, published several essays in student-run journals,[13] and in 1907 he briefly took Russian lessons. He attempted to found a literary journal with his brother, New Life, but before its first publication its other writers and its financial backers all abandoned the project, and it failed. In 1909 Lu and his brother published their translations of Western fiction, including Edgar Allan Poe,[14] as Tales from Abroad, but the book sold only 41 copies of the 1,500 copies that were printed. The publication failed for many reasons: it was only sold in Tokyo, which did not have a large Chinese population, and in a single silk shop in Shanghai. Additionally, Lu wrote in Literary Chinese, which was very difficult for ordinary people to read.[9]

Early career

[edit]

Lu intended to study in Germany in 1909, but did not have sufficient funds, and was forced to return home. Between 1909 and 1911 he held a number of brief teaching positions at local colleges and secondary schools that he felt were unsatisfying, partly to support his brother Zuoren's studies in Japan.[15]

Lu spent these years in traditional Chinese literary pursuits: collecting old books, researching pre-modern Chinese fiction, reconstructing ancient tombstone inscriptions,[16] and compiling the history of his native town, Shaoxing. He explained to an old friend that his activities were not "scholarship", but "a substitute for 'wine and women'". In his personal letters he expressed disappointment about his own failure, China's political situation, and his family's continuing impoverishment.

In 1911 he returned to Japan to retrieve his brother, Zuoren, so that Zuoren could help with the family finances. Zuoren wanted to remain in Japan to study French, but Lu wrote that "French... does not fill stomachs". He encouraged another one of his brothers, Jianren, to become a botanist.[15] He began to drink heavily, a habit he continued for the rest of his life. In 1911 he wrote his first short story, Nostalgia, but he was so disappointed with it that he threw it away. Zuoren saved it, and had it successfully published two years later under his own name.[16]

In February 1912, shortly after the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty and was followed by the founding of the Republic of China, Lu gained a position at the national Ministry of Education. He was hired in Nanjing, but then moved with the ministry to Beijing, where he lived from 1912 to 1926.[17] At first, his work consisted almost completely of copying books, but he was later appointed Section Head of the Social Education Division, and eventually to the position of Assistant Secretary. Two of his major accomplishments in office were the renovation and expansion of the National Library of China in Beijing, the establishment of the Natural History Museum, and the establishment of the Library of Popular Literature.[15]

Together with Qian Daosun and Xu Shoushang, he designed the Twelve Symbols national emblem in 1912.

Between 1912 and 1917 he was a member of an ineffectual censorship committee, informally studied Buddhist sutras, lectured on fine arts, wrote and self-published a book on the history of Shaoxing, and edited and self-published a collection of folk stories from the Tang and Song dynasties.[15] He collected and self-published an authoritative book on the work of an ancient poet, Ji Kang, and wrote A Brief History of Chinese Fiction, a work which, because traditional scholars had not valued fiction, had little precedent in China.[17] After Yuan Shikai declared himself the Emperor of China in 1915, Lu was briefly forced to participate in rituals honoring Confucius, which he ridiculed in his diaries.[15]

In 1917, an old friend of Lu's, Qian Xuantong, invited Lu to write for New Youth, a radical populist literary magazine that had recently been founded by Chen Duxiu, which also inspired a great number of younger writers such as Mao Dun. At first Lu was skeptical that his writing could serve any social purpose. He told Qian: "Imagine an iron house without windows, absolutely indestructible, with many people fast asleep inside who will soon die of suffocation. But you know since they will die in their sleep, they will not feel the pain of death. Now if you cry aloud to wake a few of the lighter sleepers, making those unfortunate few suffer the agony of irrevocable death, do you think you are doing them a good turn?"[18]: 134 Qian replied, "But if a few awake, you can't say that there is no hope of destroying the iron house."[18]: 134–135 Shortly afterwards, in 1918 Lu wrote the first short story published in his name, "Diary of a Madman", for the April 2, 1918 magazine issue.[19][20]

Lu recounted the conversation in his short story collection, Call to Arms.[18]: 134 It is widely known in China as a metaphor for the traditional Chinese cultural values and norms that Lu opposed.[18]: 134–135

After the publication of "Diary of a Madman", the story was praised for its anti-traditionalism, its synthesis of Chinese and foreign conventions and ideas, and its skillful narration, and Lu became recognized as one of the leading writers of the New Culture Movement.[21] Lu continued writing for the magazine, and produced his most famous stories for New Youth between 1917 and 1921. These stories were collected and re-published in Nahan ("Outcry") in 1923.[22]

In 1919, Lu moved his family from Shaoxing to a large compound in Beijing,[15] where he lived with his mother, his two brothers, and their Japanese wives. This living arrangement lasted until 1923, when Lu had a falling out with his brother, Zuoren, after which Lu moved with his wife and mother to a separate house. Neither Lu nor Zuoren ever publicly explained the reason for their disagreement, but Zuoren's wife later accused Lu of making sexual advances towards her.[23] Some writers have speculated that their relationship may have worsened as a result of issues related to money, that Lu walked in on Zuoren's wife bathing, or that Lu had an inappropriate "relationship" with Zuoren's wife in Japan that Zuoren later discovered. After the falling out with Zuoren, Lu became depressed.[22]

In 1920, Lu began to lecture part-time at several colleges, including Peking University, Beijing Normal University, and Beijing Women's College, where he taught traditional fiction and literary theory. His lecture notes were later collected and published as A Brief History of Chinese Fiction. He was able to work part-time because he only worked at the Education Ministry three days a week for three hours a day. In 1923 he lost his front teeth in a rickshaw accident, and in 1924 he developed the first symptoms of tuberculosis. In 1925 he founded a journal, Wilderness, and established the "Weiming Society" in order to support young writers and encourage the translation of foreign literature into Chinese.[22]

In the 20 years after the 1911 revolution there was a flowering of literary activity with dozens of journals. The goal was to reform the Chinese language to make universal education possible. Lu Xun was an active participant. His greatest works, such as "Diary of a Madman" and Ah Q, exemplify this style of "peasant dirt literature" (Chinese: 乡土文学; pinyin: xiāngtǔ wénxué). The language is fresh and direct. The subjects are country peasants.

In 1925, Lu began what may have been his first meaningful romantic relationship, with one of his students at the Beijing Women's College, Xu Guangping.[24] In March 1926 there was a mass student protest against the warlord Feng Yuxiang's collaboration with the Japanese. The protests degenerated into a massacre, in which two of Lu's students from Beijing Women's College were killed. Lu's public support for the protesters forced him to flee from the local authorities. Later in 1926, when the warlord troops of Zhang Zuolin and Wu Peifu took over Beijing, Lu left northern China and fled to Xiamen.[22]

After arriving in Xiamen, later in 1926, Lu began teaching at Xiamen University, but was disappointed by the petty disagreements and unfriendliness of the university's faculty. During the short time he lived in Xiamen, Lu wrote his last collection of fiction, Old Tales Retold, which would not be published until several years later, and most of his autobiography, published as Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk. He also published a collection of prose poetry, entitled Wild Grass.[22]

In January 1927, he and Xu moved to Guangzhou, where he was hired as the head of the Chinese literature department at Sun Yat-sen University. His first act in his position was to hire Xu as his personal assistant, as well as Xu Shoushang, one of his old classmates from Japan, as a lecturer. While in Guangzhou, he edited numerous poems and books for publication, and served as a guest lecturer at Whampoa Academy. Through his students, he established connections within both the Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

After the Shanghai massacre in April 1927, he attempted to secure the release of several students through the university, but failed. His failure to save his students led him to resign from his position at the university, and he left for the Shanghai International Settlement in September 1927. By the time he left Guangzhou, he was one of the most famous intellectuals in China.[25]

In 1927 Lu was considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature, for the short story The True Story of Ah Q, despite a poor English translation and annotations that were nearly double the size of the text.[26] Lu rejected the possibility of accepting the nomination. Later, he renounced writing fiction or poetry in response to China's deteriorating political situation and his own poor emotional state, and restricted himself to writing argumentative essays.[27]

Later career

[edit]

In 1929, he visited his mother, and reported that she was pleased at the news of Guangping's pregnancy.[25] Xu Guangping gave birth to a son named Haiying on 27 September. She was in labor with the baby for 27 hours. The child's name meant simply "Shanghai infant". His parents chose the name thinking that he could change it himself later, but he never did so. Haiying was Lu Xun's only child.[28]

After moving to Shanghai, Lu rejected all regular teaching positions (though he sometimes gave guest lectures at different campuses), and for the first time was able to make a living solely as a professional writer, with a monthly income of roughly 500 yuan. He was also appointed by the government as a "specially appointed writer" by the national Ministry of Higher Education, which secured him an additional 300 yuan per month.

He began to study and identify with Marxist politics, made contact with local CCP members, and became involved in literary disputes with other leftist writers in the city. In 1930 Lu became one of the co-founders of the League of Left-Wing Writers, but shortly after he moved to Shanghai other leftist writers accused him of being "an evil feudal remnant", the "best spokesman of the bourgeoisie", and "a counterrevolutionary split personality". The League continued in various forms until 1936, when the constant disputes among its members led the CCP to dissolve it.[25]

In January 1931, the Kuomintang passed new, stricter censorship laws, allowing for writers producing literature deemed "endangering the public" or "disturbing public order" to be imprisoned for life or executed. Later that month he went into hiding. In early February, less than a month later, the Kuomintang executed twenty-four local writers (including five who belonged to the League) whom they had arrested under this law.

After the execution of the "24 Longhua Martyrs"[25] (in addition to other students, friends, and associates),[29] Lu's political views became distinctly anti-Kuomintang. In 1933 Lu met Edgar Snow. Snow asked Lu whether there were any Ah Q's left in China. Lu responded, "It's worse now. Now it's Ah Q's who are running the country."[25]

Despite the unfavorable political climate, Lu Xun contributed regularly to a variety of periodicals in the 1930s, including Lin Yutang's humor magazine The Analects Fortnightly, and corresponded with writers in Japan as well as China.[30]

Although he had renounced writing fiction years before, in 1934 he published his last collection of short stories, Old Tales Retold.[25] In 1935, he sent a telegram to CCP forces in Shaanxi congratulating them on the recent completion of their Long March. The CCP requested that he write a novel about the communist revolution set in rural China, but he declined, citing his lack of background and understanding of the subject.[31]

Lu was a heavy smoker, which may have contributed to the deterioration of his health throughout his last year. By 1936 he had developed chronic tuberculosis, and in March of that year he was stricken with bronchial asthma and a fever. The treatment for this involved draining 300 grams of fluid in the lungs through a puncture.

From June to August, he was again sick, and his weight dropped to only 83 pounds (38 kg). He recovered somewhat, and wrote two essays in the fall reflecting on mortality. These included "Death", and "This Too Is Life".[32] A month before his death, he wrote: "Hold the funeral quickly... do not stage any memorial services. Forget about me, and care about your own life – you're a fool if you don't." Regarding his son, he wrote: "On no account let him become a good-for-nothing writer or artist."[33]

Death

[edit]At 3:30 am on the morning of 18 October 1936, the author woke having great difficulty breathing. Dr. Sudo, his physician, was summoned, and Lu Xun was given injections to relieve the pain. His wife was with him throughout that night. Lu Xun died at 5:11 am the next morning, 19 October.[32] Lu's remains were interred in a mausoleum within Lu Xun Park in Shanghai. Mao Zedong later made the calligraphic inscription above his tomb.

He was survived by his son, Zhou Haiying.

Legacy

[edit]

Lu Xun has been described by Nobel laureate Kenzaburō Ōe as "the greatest writer Asia produced in the 20th century."[34] Shortly after Lu Xun's death, Mao Zedong called him "the saint of modern China", but used his legacy selectively to promote his own political goals. In 1942, he quoted Lu out of context to tell his audience to be "a willing ox" like Lu Xun was, but told writers and artists who believed in freedom of expression that, because CCP areas were already liberated, they did not need to be like Lu Xun. After the People's Republic of China was established in 1949, CCP literary theorists portrayed his work as orthodox examples of communist literature, yet every one of Lu's close disciples from the 1930s was purged. Mao admitted that, had Lu survived until the 1950s, he would "either have gone silent or gone to prison".[35]

Party leaders depicted him as "drawing the blueprint of the communist future" and Mao Zedong defined him as the "chief commander of China's Cultural Revolution," although Lu did not join the party. During the 1920s and 1930s Lu Xun and his contemporaries often met informally for free-wheeling intellectual discussions, but after the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 the Party sought more control over intellectual life in China, and this type of intellectual independence was suppressed, often violently.

Finally, Lu Xun's satirical and ironic writing style itself was discouraged, ridiculed, then as often as possible destroyed. In 1942, Mao wrote that "the style of the essay should not simply be like Lu Xun's. [In a Communist society] we can shout at the top of our voices and have no need for veiled and round-about expressions, which are hard for the people to understand."[36] In 2007, some of his bleaker works were removed from school textbooks. Julia Lovell, who has translated Lu Xun's writing, speculated that "perhaps also it was an attempt to discourage the youth of today from Lu Xun's inconveniently fault-finding habits."[37]

During the Cultural Revolution, the CCP both hailed Lu Xun as one of the fathers of communism in China, yet ironically suppressed the very intellectual culture and style of writing that he represented. Some of his essays and writings are now part of the primary school and middle school compulsory curriculum in China.[38]

Lu completed volumes of translations, notably from Russian. He particularly admired Nikolai Gogol and made a translation of Dead Souls. His own first story's title, "Diary of a Madman", was inspired by Gogol's story of the same name. As a left-wing writer, Lu played an important role in the development of modern Chinese literature. His books were and remain highly influential and popular today, both in China and internationally. Lu Xun's works appear in high school textbooks in both China and Japan. He is known to Japanese by the name Rojin (ロジン; 魯迅).

Because of his leftist political involvement and the role his works played in the subsequent history of the People's Republic of China, Lu Xun's works were banned in Taiwan until the late 1980s.[39] He was among the early supporters of the Esperanto movement in China.

Lu Xun's importance to modern Chinese literature lies in the fact that he contributed significantly to nearly every modern literary medium during his lifetime. He wrote in a clear lucid style, which was to influence many generations, in stories, prose poems and essays. Lu Xun's two short story collections, Nahan (Call to Arms) and Panghuang (Wandering), are often acclaimed as classics of modern Chinese literature. Lu Xun's translations were important at a time when foreign literature was seldom read, and his literary criticisms remain acute and persuasively argued.

Lu Xun was also a leader of the Woodcut Movement in China (1930–1950) and widely recognized as a pioneer of the rise of the woodcut print in China.[40] After encountering new printmaking techniques in Japan, Lu embraced the art form, envisioning it as a medium to promote social change and "an alternative socialist road to art."[41] Through writings, lectures, and woodcut print publications, Lu Xun was instrumental in inspiring a generation in China towards the black-and-white woodcut.[42]

The work of Lu Xun has also received attention outside China. In 1986, Fredric Jameson cited "Diary of a Madman" as the "supreme example" of the "national allegory" form that all Third World literature takes.[43] Gloria Davies compares Lu Xun to Nietzsche, saying that both were "trapped in the construction of a modernity which is fundamentally problematic".[44] According to Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Lu Xun cultivated an ambiguous standpoint towards Nietzsche, a mixture of attraction and repulsion, the latter because of Nietzsche's excesses in style and content.[45]

- A major literature prize in China, the Lu Xun Literary Prize is named after him.

- Asteroid (233547) 2007 JR27 was named after him.

- A crater on Mercury is named after him.

- The artist Shi Lu chose the second half of his pen name to reflect his admiration for Lu Xun.[46]

Style and thought

[edit]Lu Xun was a versatile writer. He wrote using both traditional Chinese conventions and 19th century European literary forms. His style has been described in equally broad terms, conveying both "sympathetic engagement" and "ironic detachment" at different moments.[47] Particularly in his early novellas, Lu wrote about characters who were weak, indecisive, frustrated, and largely the victims of oppressive Chinese culture.[48]: 125

His essays are often very incisive in his societal commentary, and in his stories his mastery of the vernacular language and tone make some of his literary works (like "The True Story of Ah Q") hard to convey through translation. In them, he frequently treads a fine line between criticizing the follies of his characters and sympathizing with those very follies. Lu Xun was a master of irony and satire (as can be seen in "The True Story of Ah Q") and yet could also write impressively direct prose ("My Old Home", "A Little Incident").

Lu Xun is typically regarded by Mao Zedong as the most influential Chinese writer who was associated with the May Fourth Movement. He produced harsh criticism of social problems in China, particularly in his analysis of the "Chinese national character". He was sometimes called a "champion of common humanity".[by whom?][citation needed]

Lu Xun felt that the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 had been a failure. In 1925 he opined, "I feel the so-called Republic of China has ceased to exist. I feel that, before the revolution, I was a slave, but shortly after the revolution, I have been cheated by slaves and have become their slave." He even recommended that his readers heed the critique of Chinese culture in Chinese Characteristics by the missionary writer Arthur Smith. His disillusionment with politics led him to conclude in 1927 that "revolutionary literature" alone could not bring about radical change. Rather, "revolutionary men" needed to lead a revolution using force.[49] In the end, he experienced profound disappointment with the new Nationalist government, which he viewed as ineffective and even harmful to China.

Lu contended that "[i]f Chinese characters are not exterminated, there can be no doubt that China will perish."[50]

Bibliography

[edit]Lu Xun's works became known to English readers as early as 1926 with the publication in Shanghai of The True Story of Ah Q, translated by George Kin Leung, and more widely beginning in 1936 with an anthology edited by Edgar Snow and Nym Wales Living China, Modern Chinese Short Stories, in which Part One included seven of Lu Xun's stories and a short biography based on Snow's talks with Lu Xun.[51] However, there was not a complete translation of the fiction until the four-volume set of his writings, which included Selected Stories of Lu Hsun translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang. Another full selection was William A. Lyell's Diary of a Madman and Other Stories (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990). In 2009, Penguin Classics published a complete translation by Julia Lovell of his fiction, The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China: The Complete Fiction of Lu Xun, which the scholar Jeffrey Wasserstrom[52] said "could be considered the most significant Penguin Classic ever published."[53]

The Lyrical Lu Xun: a Study of his Classical-style Verse—a book by Jon Eugene von Kowallis (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996) – includes a complete introduction to Lu Xun's poetry in the classical style, with Chinese characters, literal and verse translations, and a biographical introduction which summarizes his life in relation to his poetry.

In 2017, Harvard University Press published a book of his essays translated by Eileen J. Cheng, titled Jottings under Lamplight.

Short stories

[edit]- Nostalgia (1913) 吶喊 (pinyin: Nàhǎn),1923, translated as Call to Arms (Yang and Yang), Cheering from the Sidelines (Lyell) and Outcry (Lovell):

- Diary of a Madman (Chinese: 狂人日記; pinyin: Kuángrén Rìjì), 1918

- Kong Yiji (Chinese: 孔乙己; pinyin: Kǒng Yǐjǐ), 1918[48]: 125

- Medicine (Chinese: 藥; pinyin: Yào), 1919[48]: 125

- Tomorrow (Chinese: 明天; pinyin: Míngtiān), 1920

- An Incident (Chinese: 一件小事; pinyin: Yījiàn Xiǎoshì), 1920

- The Story of Hair (Chinese: 頭髮的故事; pinyin: Tóufà de gùshì), 1920

- A Storm in a Teacup (Chinese: 風波; pinyin: Fēngbō), 1920

- My Old Home, also translated as "Hometown" (Chinese: 故鄉; pinyin: Gùxiāng), 1921[48]: 125

- The Dragon Boat Festival, also translated as "The Double Fifth Festival"[citation needed] (Chinese: 端午節; pinyin: Duānwǔjié), 1922

- The White Light (Chinese: 白光; pinyin: Báiguāng), 1922

- The Rabbits and the Cat (Chinese: 兔和貓; pinyin: Tù hé Māo), 1922

- The Comedy of the Ducks (Chinese: 鴨的喜劇; pinyin: Yā de Xǐjù), 1922

- Village Opera (Chinese: 社戲; pinyin: Shèxì), 1922

- Preface to Call to Arms, 1922

徬徨, 1926, translated as Wandering (Yang and Yang), Wondering Where to Turn (Lyell) and Hesitation (Lovell):

- The New Year's Sacrifice (Chinese: 祝福; pinyin: Zhùfú), 1924

- In the Wine Shop, also translated as "In the Drinking House" (Chinese: 在酒楼上; pinyin: Zài Jiǔlóu shàng), 1924

- A Happy Family (Chinese: 幸福的家庭; pinyin: Xìngfú de Jiātíng), 1924

- Soap (Chinese: 肥皂; pinyin: Féizào), 1924

- The Eternal Flame, 1924

- Public Exhibition, 1925

- Old Mr. Gao, 1925

- The Misanthrope, also translated as "The Loner" (Chinese: 孤獨者; pinyin: Gūdú Zhě), 1925

- Regret for the Past, also translated as "Sadness", or "Regrets for the Past" (Chinese: 傷逝; Chinese: Shāngshì), 1925

- Brothers, 1925[citation needed]

- Divorce (Chinese: 離婚; pinyin: Líhūn), 1925

故事新編 (1935), translated as Old Tales Retold (Yang and Yang) and Old Stories Retold (Lovell):

- Mending Heaven, 1935

- The Flight to the Moon (Chinese: 奔月; pinyin: Bēn Yuè), 1926

- Curbing the Flood, 1935

- Gathering Vetch, 1935

- Forging the Swords (Chinese: 鑄劍; pinyin: Zhù Jiàn), 1926

- Leaving the Pass, 1935

- Opposing Aggression, 1934

- Resurrect the Dead, 1935

Novella

[edit]- The True Story of Ah Q (Chinese: 阿Q正傳; pinyin: Ā Q Zhèngzhuàn), 1921

Essays

[edit]- "My Views on Chastity", 1918

- "What Is Required to Be a Father Today", 1919

- "Knowledge Is a Crime", 1919

- "What Happens After Nora Walks Out?" Based on a talk given at the Beijing Women's Normal College, 26 December 1923. In Ding Ling and Lu Hsun, The Power of Weakness. The Feminist Press (2007), pp. 84–93.[54]

- "My Moustache", 1924

- "Thoughts Before the Mirror", 1925

- "On Deferring Fair Play" (1925)

Miscellaneous

[edit]- 中國小說史略 (1925), based on lectures from 1920, translated as A Brief History of Chinese Fiction (Yang and Yang, 1959)

- 野草 (pinyin: Yěcǎo), 1927, prose poems, translated as Wild Grass (Yang and Yang, 2003); Weeds (Turner, 2019); and Wild Grass (Cheng, 2022)

- 唐宋傳奇集,1927–28, editor of an anthology of chuanqi, translated as Anthology of Tang and Song Tales: The Tang Song Chuanqi Ji of Lu Xun (World Scientific, 2020)

- 朝花夕拾, 1932, a collection of essays about his youth, translated as Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk (Yang and Yang, 1976) and Morning Blossoms Gathered at Dusk (Cheng, 2022)

- 熱風

- 華蓋集

- 華蓋集続編

- 墳

- 而已集

- 三閑集

- 二心集

- 偽自由書

- 南腔北調集

- 准風月談

- 花邊文學

- 且介亭雑文

- 且介亭雑文二集

- 且介亭雑文末編

- 集外集

- 集外集拾遺

- 集外集拾遺補編

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Zhou Zuoren (2002). 魯迅的青年時代 [Lu Xun's youth]. Hebei Education Press. ISBN 978-7-5434-4391-4.

- ^ Kowallis 10

- ^ Kowallis 11–12

- ^ a b c Denton "Early Life"

- ^ a b c d Lovell 2009 xv

- ^ Lee, Leo Ou-fan (1977). Goldman, Merle (ed.). Modern Chinese Literature in the May Fourth Era. Harvard University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-674-57911-8.

Lu Xun was lured back briefly to take the first-level district examination in 1898.

- ^ a b c d e Denton "WESTERN EDUCATION: 1898–1902"

- ^ a b c Lovell 2009 xvi

- ^ a b c d e f g Denton "JAPAN: 1902–09"

- ^ a b c d Qian, Ying (2024). Revolutionary Becomings: Documentary Media in Twentieth-Century China. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231204477.

- ^ Kowallis 22

- ^ Veg

- ^ Kowallis 20–23

- ^ Hao, Ruijuan (Winter 2009). "Edgar Allan Poe in Contemporary China". The Edgar Allan Poe Review. 10 (3): 117–122. doi:10.2307/41506373. JSTOR 41506373. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Denton "HOME AGAIN"

- ^ a b Lovell 2009 xviii

- ^ a b Kowallis 26

- ^ a b c d Shi, Song (2023). China and the Internet: Using New Media for Development and Social Change. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9781978834736.

- ^ Lovell 2009 xx

- ^ Jin 2017, pp. 254–259.

- ^ Lovell 2009 xxi

- ^ a b c d e Denton "MAY FOURTH: 1917–26"

- ^ Lovell 2009 xxv

- ^ Lovell 2009 xxvi

- ^ a b c d e f Denton "MOVE TO THE LEFT: 1927–1936"

- ^ Kowallis 3

- ^ Lovell 2006 84

- ^ Lu & Xu 64

- ^ Lovell 2009 xxviii

- ^ Christopher Rea, The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015), pp. 132, 148-149.

- ^ Lovell 2009 xxx

- ^ a b Jenner

- ^ Lovell xxxii

- ^ Jon Kowallis (University of Melbourne) (1996). "Interpreting Lu Xun". Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews. 18: 153–164. doi:10.2307/495630. JSTOR 495630.

- ^ Lovell 2009 xxi–xxxiii

- ^ "TALKS AT THE YENAN FORUM ON LITERATURE AND ART". www.marxists.org.

- ^ Lovell, Julia (12 June 2010). "China's conscience". Guardian.

- ^ Goldman, Merle (September 1982). "The Political Use of Lu Xun". The China Quarterly. 91 (91). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 446–447. doi:10.1017/S0305741000000655. JSTOR 653366. S2CID 154642676.

- ^ Chen, Fangming (1994). 典範的追求 [The Quest for Paradigm] (in Chinese). 聯合文學出版社. p. 318. ISBN 978-957-522-076-1.

一九四九年國民黨逃亡到台灣,展開積極的反共政策,從此出現了以後長達四十年的反魯迅傳統。

- ^ "Gan Zhenglun | Lu Xun and Uchiyama at the Woodblock-Printing Class | China". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Corban, Caroline; Art, Bowdoin Journal of. "Lu Xun (1881-1936) and the Modern Woodcut Movement". Bowdoin Journal of Art.

- ^ "Lu Xun's Legacy: Printmaking in Modern China | SOAS". www.soas.ac.uk. 20 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Jameson, Fredric (Autumn 1986). "Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism". Social Text. 15 (15). Duke University Press: 65–88. doi:10.2307/466493. JSTOR 466493.

- ^ Davies, Gloria (July 1992). "Chinese Literary Studies and Post-Structuralist Positions: What Next?". The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs. 28 (28). Contemporary China Center, Australian National University: 67–86. doi:10.2307/2950055. JSTOR 2950055. S2CID 155250111.

- ^ Arena, Leonardo Vittorio (2012). Nietzsche in China in the XXth Century. ebook.

- ^ King, Richard (2010). Art in Turmoil: The Chinese Cultural Revolution, 1966–76. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-9888028641.

- ^ Hesford, Walter (April 1992). "Overt Appropriation". College English. 54 (4). National Council of Teachers of English: 406–417. doi:10.2307/377832. JSTOR 377832.

- ^ a b c d Laikwan, Pang (2024). One and All: The Logic of Chinese Sovereignty. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503638815.

- ^ Lee, Leo Ou-Fan (July 1976). "Literature on the Eve of Revolution: Reflections on Lu Xun's Leftist Years, 1927–1936". Modern China. 2 (3). Sage Publications, Inc.: 277–326. doi:10.1177/009770047600200302. JSTOR 189028. S2CID 220736707.; Lydia Liu,"Translating National Character: Lu Xun and Arthur Smith," Ch 2, Translingual Practice: Literature, National Culture, and Translated Modernity: China 1900–1937 (Stanford 1995).

- ^ Mullaney, Thomas S. (2024). The Chinese Computer: a Global History of the Information Age. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780262047517.

- ^ New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1937. Reprinted: Westport, CT: Hyperion Press, 1973. ISBN 088355092X.

- ^ Jeffrey Wasserstrom, UC Irvine, Department of History

- ^ Wasserstrom, Jeffrey (7 December 2009). "China's Orwell". TIME.

- ^ "What Happens after Nora Walks Out". MCLC Resource Center. 19 October 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Arena, Leonardo Vittorio. Nietzsche in China in the XXth Century. 2012.

- Davies, Goria. Lu Xun's Revolution: Writing in a Time of Violence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 2013. ISBN 9780674072640.

- Denton, Kirk (2002), Lu Xun Biography, MCLC Resource Center Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Jenner, W.J.F. "Lu Xun's Last Days and after". The China Quarterly. 91. (September 1982). 424–445.

- Jin, Ha (2017). "Zhou Yucai writes ʽʽA Madman's Diaryʻʻ under the Pen Name Lu Xin". In Wang, David Der-wei (ed.). A New Literary History of Modern China. Harvard, Ma: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 254–259. ISBN 978-0-674-97887-4.

- Kowallis, Jon. The Lyrical Lu Xun. United States of America: University of Hawai'i Press. 1996. ISBN 0-8248-1511-4

- Lee, Leo Ou-Fan. Lu Xun and His Legacy. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1985. ISBN 0520051580.

- Lee, Leo Ou-Fan. Voices from the Iron House: A Study of Lu Xun. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1987. ISBN 0253362636.

- Lovell, Julia. The Politics of Cultural Capital: China's Quest for a Nobel Prize in Literature. United States of America: University of Hawai'i Press. 2006. ISBN 0-8248-2962-X

- Lovell, Julia. "Introduction". In Lu Xun: The Real story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China, The Complete Fiction of Lu Xun. England: Penguin Classics. 2009. ISBN 978-0-140-45548-9.

- Lu Xun and Xu Guangping. Love-letters and Privacy in Modern China: The Intimate Lives of Lu Xun and Xu Guangping. Ed. McDougall, Bonnie S. Oxford University Press. 2002.

- Lyell, William A. Lu Hsün's Vision of Reality. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1976. ISBN 0520029402.

- Pollard, David E. The True Story of Lu Xun. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. 2002. ISBN 9629960605.

- Sze, Arthur (Ed.) Chinese Writers on Writing. Arthur Sze. Trinity University Press. 2010.

- Veg, Sebastian. "David Pollard, The True Story of Lu Xun". China Perspectives. 51. January–February 2004. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Kaldis, Nicholas A. The Chinese Prose Poem: A Study of Lu Xun's Wild Grass (Yecao). Cambria Press. 2014. ISBN 9781604978636.

External links

[edit]- Special Issue about Lu Xun (in Japanese) at web.bureau.tohoku.ac.jp

- Lu Xun bibliography at u.osu.edu/mclc/

- Lu Xun webpage (in Chinese)

- Selected works by Lu Xun (in Chinese)

- A Brief Biography of Lu Xun with Many Pictures

- Reference Archive: Lu Xun (Lu Hsun) at www.marxists.org

- An Outsider's Chats about Written Language, a long essay by Lu Xun on the difficulties of Chinese characters

- Works by Xun Lu at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Lu Xun at the Internet Archive

- Works by Lu Xun at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Lu Xun

- 1881 births

- 1936 deaths

- 20th-century Chinese male writers

- 20th-century Chinese short story writers

- 20th-century Chinese novelists

- 20th-century Chinese poets

- 20th-century Chinese translators

- 20th-century Chinese historians

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers

- Academic staff of Peking University

- Academic staff of Beijing Normal University

- Academic staff of Xiamen University

- Academic staff of Sun Yat-sen University

- Chinese literary critics

- Scholars of Chinese literature

- Chinese magazine writers

- Chinese magazine editors

- Chinese male short story writers

- Chinese Marxist writers

- Chinese expatriates in Japan

- Chinese government officials

- Chinese Esperantists

- Critics of Confucianism

- Educators from Shaoxing

- Hangzhou High School alumni

- Modernist writers

- Poets from Zhejiang

- 20th-century Chinese essayists

- Short story writers from Zhejiang

- Tohoku University alumni

- Writers about activism and social change

- Writers from Shaoxing

- Burials in Shanghai

- Chinese language reform

- Chinese satirists

- Chinese satirical novelists