Anti-Chinese sentiment

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Anti-Chinese sentiment (also referred to as Sinophobia) is the fear or dislike of China, Chinese people and/or Chinese culture.[1][2][3][4][5][6] In the western world, fear over the increasing economic and military power of China, its technological prowess and cultural reach, as well as international influence, has driven persistent and selectively negative media coverage of China. This is often aided and abetted by policymakers and politicians,[7][8] whose actions are driven both by prejudice and expedience.[9]

It is frequently directed at Chinese minorities which live outside China and involves immigration, nationalism, political ideologies, disparity of wealth, the past tributary system of Imperial China, majority-minority relations, imperial legacies, and racism.[10][11][12][note 1]

A variety of popular cultural clichés and negative stereotypes of Chinese people have existed around the world since the twentieth century, and they are frequently conflated with a variety of popular cultural clichés and negative stereotypes of other Asian ethnic groups, known as the Yellow Peril.[15] Some individuals may harbor prejudice or hatred against Chinese people due to history, racism, modern politics, cultural differences, propaganda, or ingrained stereotypes.[15][16]

The COVID-19 pandemic led to resurgent Sinophobia, whose manifestations range from as subtle acts of discrimination such as microaggression and stigmatization, exclusion and shunning, to more overt forms, such as outright verbal abuse, slurs and name-calling, and sometimes physical violence.[17][18][19][20][21]

Statistics and background

[edit]| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Neutral | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +69 | ||||

| +65 | ||||

| +58 | ||||

| +48 | ||||

| +35 | ||||

| +34 | ||||

| +34 | ||||

| +31 | ||||

| +29 | ||||

| +28 | ||||

| +26 | ||||

| +24 | ||||

| +14 | ||||

| +12 | ||||

| +11 | ||||

| +5 | ||||

| 0 | ||||

| -1 | ||||

| -7 | ||||

| -8 | ||||

| -16 | ||||

| -20 | ||||

| -26 | ||||

| -30 | ||||

| -33 | ||||

| -33 | ||||

| -35 | ||||

| -38 | ||||

| -42 | ||||

| -44 | ||||

| -46 | ||||

| -47 | ||||

| -48 | ||||

| -48 | ||||

| -50 | ||||

| -54 | ||||

| -56 | ||||

| -56 | ||||

| -56 | ||||

| -61 | ||||

| -71 | ||||

| -83 |

In 2013, Pew Research Center from the United States conducted a survey on sinophobia, finding that China was viewed favorably in half (19 of 38) of the nations surveyed, excluding China itself. The highest levels of support came from Asia in Malaysia (81%) and Pakistan (81%); African nations of Kenya (78%), Senegal (77%) and Nigeria (76%); as well as Latin America, particularly in countries heavily engaging with the Chinese market, such as Venezuela (71%), Brazil (65%) and Chile (62%).[23]

Anti-China sentiment

[edit]Anti-China sentiment has remained persistent in the West and other Asian countries: only 28% of Germans and Italians and 37% of Americans viewed China favorably while in Japan, just 5% of respondents had a favorable opinion of the country. 11 of the 38 nations viewed China unfavorably by over 50%. Japan was polled to have the most anti-China sentiment, where 93% saw the People's Republic in a negative light. There were also majorities in Germany (64%), Italy (62%), and Israel (60%) who held negative views of China. Germany saw a large increase of anti-China sentiment, from 33% disfavor in 2006 to 64% in the 2013 survey, with such views existing despite Germany's success in exporting to China.[23]

Positive views of China

[edit]Respondents in the Balkans have held generally positive views of China, according to 2020 polling. An International Republican Institute survey from February to March found that only in Kosovo (75%) did most respondents express an unfavourable opinion of the country, while majorities in Serbia (85%), Montenegro (68%), North Macedonia (56%), and Bosnia (52%) expressed favourable views.[24] A GLOBSEC poll on October found that the highest percentage of those who saw China as a threat were in the Czech Republic (51%), Poland (34%), and Hungary (24%), while it was seen as least threatening in Balkan countries such as Bulgaria (3%), Serbia (13%), and North Macedonia (14%). Reasons for threat perception were generally linked to the country's economic influence.[25]

According to Arab Barometer polls, views of China in the Arab world have been relatively positive, with data from March to April 2021 showing that most respondents in Algeria (65%), Morocco (62%), Libya (60%), Tunisia (59%), and Iraq (56%) held favourable views of the country while views were less favourable in Lebanon (38%) and Jordan (34%).[26]

Impact of COVID pandemic

[edit]Global polling in 2020 amidst the COVID-19 pandemic reported a decrease in favourable views of China, with an Ipsos poll done in November finding those in Russia (81%), Mexico (72%), Malaysia (68%), Peru (67%) and Saudi Arabia (65%) were most likely to believe China's future influence would be positive, while those in Great Britain (19%), Canada (21%), Germany (24%), Australia (24%), Japan (24%), the United States (24%) and France (24%) were least likely.[27] A YouGov poll on August found that those in Nigeria (70%), Thailand (64%), Mexico (61%), and Egypt (55%) had more positive views of China regarding world affairs while those in Japan (7%), Denmark (13%), Britain (13%), Sweden (14%), and other Western countries had the least positive views.[28]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, victims of violence and verbal abuse range from toddlers to elderly,[20] school children and their parents,[17] and include not just mainland Chinese, but has affected also Taiwanese, Hong Kongers, members of the Chinese diaspora and other Asians who are mistaken for or associated with them.[19][17]

History

[edit]Looting and sacking of national treasures

[edit]Historical records document the existence of anti-Chinese sentiment throughout China's imperial wars.[29]

Lord Palmerston was responsible for sparking the First Opium War (1839–1842) with Qing China. He considered Chinese culture "uncivilized", and his negative views on China played a significant role in his decision to issue a declaration of war.[30] This disdain became increasingly common throughout the Second Opium War (1856–1860), when repeated attacks against foreign traders in China inflamed anti-Chinese sentiment abroad.[citation needed] Following the defeat of China in the Second Opium War, Lord Elgin, upon his arrival in Peking in 1860, ordered the sacking and burning of China's imperial Summer Palace in vengeance.[citation needed]

Chinese Exclusion Act 1882

[edit]In the United States, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed in response to growing Sinophobia. It prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers and turned those already in the country into second-class persons.[31] The 1882 Act was the first U.S. immigration law to target a specific ethnicity or nationality.[32]: 25 Meanwhile, during the mid-19th century in Peru, Chinese were used as slave labor and they were not allowed to hold any important positions in Peruvian society.[33]

Chinese workers in England

[edit]Chinese workers had been a fixture on London's docks since the mid-eighteenth century, when they arrived as sailors who were employed by the East India Company, importing tea and spices from the Far East. Conditions on those long voyages were so dreadful that many sailors decided to abscond and take their chances on the streets rather than face the return journey. Those who stayed generally settled around the bustling docks, running laundries and small lodging houses for other sailors or selling exotic Asian produce. By the 1880s, a small but recognizable Chinese community had developed in the Limehouse area, increasing Sinophobic sentiments among other Londoners, who feared the Chinese workers might take over their traditional jobs due to their willingness to work for much lower wages and longer hours than other workers in the same industries. The entire Chinese population of London was only in the low hundreds—in a city whose entire population was roughly estimated to be seven million—but nativist feelings ran high, as was evidenced by the Aliens Act of 1905, a bundle of legislation which sought to restrict the entry of poor and low-skilled foreign workers.[34] Chinese Londoners also became involved with illegal criminal organisations, further spurring Sinophobic sentiments.[34][35]

Cold War

[edit]During the Cold War, anti-Chinese sentiment became a permanent fixture in the media of the Western world and anti-communist countries following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949. From the 1950s to the 1980s, anti-Chinese sentiment was high in South Korea as a result of the Chinese intervention against the South Korean army in the Korean War (1950–1953).

In the Soviet Union, anti-Chinese sentiment became high following the hostile political relations between the PRC and the USSR from the late 1950s onward, which nearly escalated into war between the two countries in 1969. The "Chinese threat", as it was described in a letter by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, prompted expressions of anti-Chinese sentiment in the conservative Russian samizdat movement.[36]

By region

[edit]East Asia

[edit]Korea

[edit]Anti-Chinese sentiment in Korea was created in the 21st century by cultural and historical claims of China and a sense of security crisis caused by China's economic growth.[37] In the early 2000s, China's claim over the history of Goguryeo, an ancient Korean kingdom, caused tensions between both Koreas and China.[38][39] The dispute has also involved naming controversies over Paektu Mountain (or Changbai Mountain in Chinese).[40] China has been accused of trying to appropriate kimchi[41] and hanbok as part of Chinese culture,[42] along with labeling Yun Dong-ju as chaoxianzu, which have all angered South Koreans.[43]

Anti-Chinese sentiments in South Korea have been on a steady rise since 2002. According to Pew opinion polls, favorable views of China steadily declined from 66% in 2002 to 48% in 2008, while unfavorable views rose from 31% in 2002 to 49% in 2008.[23] According to surveys by the East Asia Institute, positive views of China's influence declined from 48.6% in 2005 to 38% in 2009, while negative views of it rose from 46.7% in 2005 to 50% in 2008.[44] A 2012 BBC World Service poll had 64% of South Koreans expressing negative views of China's influence, which was the highest percentage out of 21 countries surveyed including Japan at 50%.[45]

Relations further strained with the deployment of THAAD in South Korea in 2017, in which China started its boycott against Korea, making Koreans develop anti-Chinese sentiment in South Korea over reports of economic retaliation by Beijing.[46] According to a poll from the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies at Seoul National University in 2018, 46% of South Koreans found China as the most threatening country to inter-Korean peace (compared to 33% for North Korea), marking the first time China was seen as a bigger threat than North Korea since the survey began in 2007.[47] A 2022 poll from the Central European Institute of Asian Studies had 81% of South Koreans expressing a negative view of China, which was the highest out of 56 countries surveyed.[48]

Discriminatory views of Chinese people have been reported,[49][50] and ethnic-Chinese Koreans have faced prejudices including what is said, to be a widespread criminal stigma.[51][52] Increased anti-Chinese sentiments had reportedly led to online comments calling the Nanjing Massacre the "Nanjing Grand Festival" or others such as "Good Chinese are only dead Chinese" and "I want to kill Korean Chinese".[53][51]

Taiwan

[edit]Anti-Chinese sentiment in Taiwan comes from the fact that many Taiwanese, especially young people, choose to identify solely as "Taiwanese"[54] and are against having closer ties with China, like those in the Sunflower Student Movement.[55] According to a 2024 survey from Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council, Taiwanese believe that China is Taiwan's main enemy and unfriendly to Taiwan. Taiwan's government is communicating and cooperating with democratic countries such as South Korea and the United States.[56]

Taiwan's main political parties, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are some described as "anti-China".[57][58] The DPP is expressing its opposition to Chinese "imperialism" and "colonialism".[57]

In the late 1940s, the anti-mainland Chinese term "The dogs go and the pigs come" became popular in Taiwanese society as a result of dissatisfaction with the Republic of China controlled by a one-party system of KMT's rule and the February 28 incident caused by KMT regime.[citation needed]

In 2016, "Islanders' Anti-China Coalition", a radical anti-communist organization, was formed; they actively support Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Inner Mongolian independence.

Japan

[edit]After the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II in 1945, the relationship between China and Japan gradually improved. However, since 2000, Japan has seen a gradual resurgence of anti-Chinese sentiment. Many Japanese people believe that China is using the issue of the country's checkered history, such as the Japanese history textbook controversies, many war crimes which were committed by Japan's military, and official visits to the Yasukuni Shrine (in which a number of war criminals are enshrined), as both a diplomatic card and a tool to make Japan a scapegoat in domestic Chinese politics.[59] The Anti-Japanese Riots in the Spring of 2005 were another source of more anger towards China among the Japanese public. Anti-Chinese sentiments have been on a sharp rise in Japan since 2002. According to the Pew Global Attitude Project (2008), 84% of Japanese people held an unfavorable view of China and 73% of Japanese people held an unfavorable view of Chinese people, which was a higher percentage than all the other countries surveyed.[60]

A survey in 2017 suggested that 51% of Chinese respondents had experienced tenancy discrimination.[61] Another report in the same year noted a significant bias against Chinese visitors from the media and some of the Japanese locals.[62]

China

[edit]Among Chinese dissidents and critics of the Chinese government, it's popular[according to whom?] to express internalized racist sentiments which are based on anti-Chinese sentiment, promoting the usage of pejorative slurs (such as shina or locust),[63][64][65] or displaying hatred towards the Chinese language, people, and culture.[66]

Xinjiang

[edit]After the Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People's Republic of China under Mao Zedong to establish the PRC in 1949, there have been considerable ethnic tensions arising between the Han Chinese and Turkic Muslim Uyghurs.[67][68][69][70][71] This manifested itself in the 1997 Ghulja incident,[72] the bloody July 2009 Ürümqi riots,[73] and the 2014 Kunming attack.[74] According to BBC News, this has prompted China to suppress the native population and create internment camps for purported counter-terrorism efforts, which have fuelled resentment in the region.[75]

Tibet

[edit]

Tibet has complicated relations with the rest of China. Both Tibetan and Chinese are part of the Sino-Tibetan language family and share a long history. The Tang dynasty and Tibetan Empire did enter into periods of military conflict. In the 13th century, Tibet fell under the rule of the Yuan dynasty but it ceased to be with the collapse of the Yuan dynasty. The relationship between Tibet with China remains complicated until Tibet was invaded again by the Qing dynasty. Following the British expedition to Tibet in 1904, many Tibetans look back on it as an exercise of Tibetan self-defense and an act of independence from the Qing dynasty, as the dynasty was falling apart.[76] This event has left a dark chapter in their modern relations. The Republic of China failed to reconquer Tibet but the later People's Republic of China annexed Tibet and incorporated it as the Tibet Autonomous Region within China. The 14th Dalai Lama and Mao Zedong signed the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, but China was accused of not honoring the treaty[77] and led to the 1959 Tibetan uprising which was successfully suppressed by China,[78] resulting in the Dalai Lama escaping to India.[79]

Tibetans again rioted against other Chinese rule twice, in the 1987–1989 Tibetan unrest[80] and 2008 unrest, where they directed their angers against Han and Hui Chinese.[81] Both were suppressed by China and China has increased their military presence in the region, despite periodic self-immolations.[82]

Hong Kong

[edit]

Although Hong Kong's sovereignty was returned to China in 1997, only a small minority of its inhabitants consider themselves to be exclusively Chinese. According to a 2014 survey from the University of Hong Kong, 42.3% of respondents identified themselves as "Hong Kong citizens", versus only 17.8% who identified themselves as "Chinese citizens", and 39.3% gave themselves a mixed identity (a Hong Kong Chinese or a Hong Konger who was living in China).[83] By 2019, almost no Hong Kong youth identified as Chinese.[84]

The number of mainland Chinese visitors to the region has surged since the handover (reaching 28 million in 2011) and is perceived by many locals to be the cause of their housing and job difficulties. In addition to resentment due to political oppression, negative perceptions have grown through circulating online posts of mainlander misbehaviour,[85] as well as discriminatory discourse in major Hong Kong newspapers.[86][87] In 2013, polls from the University of Hong Kong suggested that 32 to 35.6 per cent of locals had "negative" feelings for mainland Chinese people.[88] However, a 2019 survey of Hong Kong residents has suggested that there are also some who attribute positive stereotypes to visitors from the mainland.[89]

In a 2015 study, mainland students in Hong Kong who initially had a more positive view of the city than of their own mainland hometowns reported that their attempts at connecting with the locals were difficult due to experiences of hostility.[90]

In 2012, a group of Hong Kong residents published a newspaper advertisement depicting mainland visitors and immigrants as locusts.[91] In February 2014, about 100 Hong Kongers harassed mainland tourists and shoppers during what they styled an "anti-locust" protest in Kowloon. In response, the Equal Opportunities Commission of Hong Kong proposed an extension of the territory's race-hate laws to cover mainlanders.[92] Strong anti-mainland xenophobia has also been documented amidst the 2019 protests,[93] with reported instances of protesters attacking Mandarin-speakers and mainland-linked businesses.[94][95]

Central Asia

[edit]Kazakhstan

[edit]In 2018, massive land reform protests were held in Kazakhstan. The protesters demonstrated against the leasing of land to Chinese companies and the perceived economic dominance of Chinese companies and traders.[96][97] Another issue which is leading to the rise of sinophobia in Kazakhstan is the Xinjiang conflict and Kazakhstan is responding to it by hosting a significant number of Uyghur separatists.[citation needed]

Kyrgyzstan

[edit]While discussing Chinese investments in the country, a Kyrgyz farmer said, "We always run the risk of being colonized by the Chinese".[98]

Survey data cited by the Kennan Institute from 2017 to 2019 had on average 35% of Kyrgyz respondents expressing an unfavourable view of China compared to 52% expressing a favourable view; the disapproval rating was higher than that of respondents from 3 other Central Asian countries.[99]

Mongolia

[edit]Mongolian nationalist and Neo-Nazi groups are reported to be hostile to China,[100] and Mongolians traditionally hold unfavorable views of the country.[101] The common stereotype is that China is trying to undermine Mongolian sovereignty in order to eventually make it part of China (the Republic of China has claimed Mongolia as part of its territory, see Outer Mongolia). Fear and hatred of erliiz (Mongolian: эрлийз, [ˈɛrɮiːt͡sə], literally, double seeds), a derogatory term for people of mixed Han Chinese and Mongol ethnicity,[102] is a common phenomena in Mongolian politics. Erliiz are seen as a Chinese plot of "genetic pollution" to chip away at Mongolian sovereignty, and allegations of Chinese ancestry are used as a political weapon in election campaigns. Several small Neo-Nazi groups opposing Chinese influence and mixed Chinese couples are present within Mongolia, such as Tsagaan Khas.[100]

Tajikistan

[edit]Resentment against China and Chinese people has also increased in Tajikistan in recent years due to accusations that China has grabbed land from Tajikistan.[103] In 2013, the Popular Tajik Social-Democrat Party leader, Rakhmatillo Zoirov, claimed that Chinese troops were violating a land-ceding arrangement by moving deeper into Tajikistan than they were supposed to.[104]

Southeast Asia

[edit]Singapore

[edit]To counteract the city state's low birthrate, Singapore's government has been offering financial incentives and a liberal visa policy to attract an influx of migrants. Chinese immigrants to the nation grew from 150,447 in 1990 to 448,566 in 2015 to make up 18% of the foreign-born population, next to Malaysian immigrants at 44%.[105] The xenophobia towards mainland Chinese is reported to be particularly severe compared to other foreign residents,[106] as they are generally looked down on as country bumpkins and blamed for stealing desirable jobs and driving up housing prices.[107] There have also been reports of housing discrimination against mainland Chinese tenants,[108] and a 2019 YouGov poll has suggested Singapore to have the highest percentage of locals prejudiced against Chinese travellers out of the many countries surveyed.[109][110]

A 2016 study found that out of 20 Chinese Singaporeans, 45% agreed that PRC migrants were rude, although only 15% expressed negative attitudes towards mainland Chinese in general.[111] Another 2016 study of Singaporean locals and (mostly mainland) Chinese students found that most respondents in both groups said they had positive experiences with each other, with only 11% of Singaporeans saying they did not.[112]

Malaysia

[edit]Due to race-based politics and Bumiputera policy, there had been several incidents of racial conflict between the Malays and Chinese before the 1969 riots. For example, in Penang, hostility between the races turned into violence during the centenary celebration of George Town in 1957 which resulted in several days of fighting and a number of deaths,[113] and there were further disturbances in 1959 and 1964, as well as a riot in 1967 which originated as a protest against currency devaluation but turned into racial killings.[114][115] In Singapore, the antagonism between the races led to the 1964 Race Riots which contributed to the expulsion of Singapore from Malaysia on August 9, 1965. The 13 May Incident was perhaps the deadliest race riot to have occurred in Malaysia with an official combined death toll of 196[116] (143 Chinese, 25 Malays, 13 Indians, and 15 others of undetermined ethnicity),[117] but with higher estimates by other observers reaching around 600-800+ total deaths.[118][119][120]

Malaysia's ethnic quota system has been regarded as discriminatory towards the ethnic Chinese (and Indian) community, in favor of ethnic Malay Muslims,[121] which has reportedly created a brain drain in the country. In 2015, supporters of Najib Razak's party reportedly marched in the thousands through Chinatown to support him, and assert Malay political power with threats to burn down shops, which drew criticism from China's ambassador to Malaysia.[122]

It was reported in 2019 that relations between ethnic Chinese Malaysians and Malays were "at their lowest ebb", and fake news posted online of mainland Chinese indiscriminately receiving citizenship in the country had been stoking racial tensions. The primarily Chinese-based Democratic Action Party in Malaysia has also reportedly faced an onslaught of fake news depicting it as unpatriotic, anti-Malay, and anti-Muslim.[123] Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been social media posts claiming the initial outbreak is "divine retribution" for China's treatment of its Muslim Uyghur population.[124]

Cambodia

[edit]The speed of Chinese resident arrivals in Sihanoukville city has led to an increase in fear and hostility towards the new influx of Chinese residents among the local population. As of 2018, the Chinese community in the city makes up almost 20% of the town's population.[125]

Philippines

[edit]The Spanish introduced the first anti-Chinese laws in the Philippine archipelago. The Spanish massacred or expelled the Chinese several times from Manila, and the Chinese responded by fleeing either to La Pampanga or to territories outside colonial control, particularly the Sulu Sultanate, which they in turn supported in their wars against the Spanish authorities.[126] The Chinese refugees not only ensured that the Sūg people were supplied with the requisite arms but also joined their new compatriots in combat operations against the Spaniards during the centuries of Spanish–Moro conflict.[127]

Furthermore, racial classification from the Spanish and American administrations has labeled ethnic Chinese as alien. This association between 'Chinese' and 'foreigner' have facilitated discrimination against the ethnic Chinese population in the Philippines; many ethnic Chinese were denied citizenship or viewed as antithetical to a Filipino nation-state.[128] In addition to this, Chinese people have been associated with wealth in the background of great economic disparity among the local population. This perception has only contributed to ethnic tensions in the Philippines, with the ethnic Chinese population being portrayed as being a major party in controlling the economy.[128]

The standoff in Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal between China and the Philippines contributes to anti-China sentiment among Filipinos. Campaigns to boycott Chinese products began in 2012. People protested in front of the Chinese Embassy and it led the embassy to issue a travel warning for its citizens to the Philippines for a year.[129]

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, scholar Jonathan Corpuz Ong has lamented that there is a great deal of hateful and racist speech on Philippine social media which "many academics and even journalists in the country have actually justified as a form of political resistance" to the Chinese government.[130] In addition, the United States government reinforced Filipinos' suspicion of China amidst the territorial disputes by conducting a disinformation campaign that amplified Filipinos' erosion of trust in Chinese COVID-19 vaccines and pandemic supplies.[131]

In 2024, the Chinese-Filipino community in the Philippines expressed concerns over the increased anti-Chinese sentiment from Filipinos resulting from issues surrounding the POGO businesses and investigations on the background of Alice Guo, the dismissed mayor of Bamban accused by Filipino authorities of having connections with a POGO business in the said municipality.[132]

Indonesia

[edit]

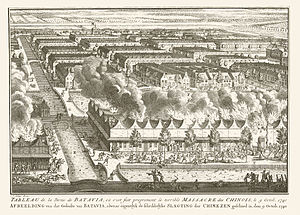

The Dutch introduced anti-Chinese laws in the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch colonialists started the first massacre of Chinese in the 1740 Batavia massacre in which tens of thousands died. The Java War (1741–43) followed shortly thereafter.[133][134][135][136][137]

The asymmetrical economic position between ethnic Chinese Indonesians and indigenous Indonesians has incited anti-Chinese sentiment among the poorer majorities. During the Indonesian killings of 1965–66, in which more than 500,000 people died (mostly non-Chinese Indonesians),[138] ethnic Chinese were killed and their properties looted and burned as a result of anti-Chinese racism on the excuse that Dipa "Amat" Aidit had brought the PKI closer to China.[139][10] In the May 1998 riots of Indonesia following the fall of President Suharto, many ethnic Chinese were targeted by other Indonesian rioters, resulting in extensive looting. However, when Chinese-owned supermarkets were targeted for looting most of the dead were not ethnic Chinese, but the looters themselves, who were burnt to death by the hundreds when a fire broke out.[140][141]

In recent years,[when?] disputes in the South China Sea led to the renewal of tensions. At first, the conflict was contained between China and Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia, with Indonesia staying neutral. However, accusations about Indonesia's lack of activities to protect its fishermen from China's fishing vessels in the Natuna Sea[142] and disinformation about Chinese foreign workers have contributed to the deterioration of China's image in Indonesia.[143][144]

Coconuts Media reported in April 2022 of online groups in the country targeting Chinese-Indonesian women for racialised sexual abuse.[145] On the other hand, a 2022 online poll done by Palacký University Olomouc had little more than 20% of Indonesian respondents viewing China negatively while over 70% held a positive view.[146][147]

Myanmar

[edit]The ongoing ethnic insurgency in Myanmar and the 1967 riots in Burma against the Chinese community displeased the PRC, which led to the arming of ethnic and political rebels by China against Burma.[148] Resentment towards Chinese investments[149] and their perceived exploitation of natural resources have also hampered the Sino-Burmese relationship.[150] Chinese people in Myanmar have also been subject to discriminatory laws and rhetoric in Burmese media and popular culture.[151]

In November 2023, pro junta supporters held protests in Naypyidaw and Yangon accusing China of supporting Operation 1027 rebels,[152][153] with some Yangon protesters threatening to attack China for its support.[154]

Thailand

[edit]Historically, Thailand (called Siam before 1939) has been seen as a China-friendly country, owing to close Chinese-Siamese relations, a large proportion of the Thai population being of Chinese descent and Chinese having been assimilated into mainstream society over the years.

In 1914, King Rama VI Vajiravudh originated the phrase "Jews of the Orient" to describe Chinese.[155]: 127 He published an essay using Western antisemitic tropes to characterize Chinese as "vampires who steadily suck dry an unfortunate victim's lifeblood" because of their perceived lack of loyalty to Siam and the fact that they sent money back to China.[155]: 127

Later, Plaek Phibunsongkhram launched a massive Thaification, the main purpose of which was Central Thai supremacy, including the oppression of Thailand's Chinese population and restricting Thai Chinese culture by banning the teaching of the Chinese language and forcing Thai Chinese to adopt Thai names.[156] Plaek's obsession with creating a pan-Thai nationalist agenda caused resentment among general officers (most of Thai general officers at the time were of Teochew background) until he was removed from office in 1944.[157] Since that, mainstream culture of the nation from the Central Thai people was replaced by Thai Chinese, and Central Thai face discrimination instead, although the Cold War may have inflamed hostility towards the mainland Chinese.[citation needed]

Hostility towards the mainland Chinese increased with the increase of visitors from China in 2013.[158][159] It has also been worsened by Thai news reports and social media postings on misbehaviour from a portion of the tourists.[160][161] In spite of this, some reports have suggested that there are still some Thais who have positive impressions of Chinese tourists.[162]

Vietnam

[edit]There are strong anti-Chinese sentiments among the Vietnamese population, stemming in part from a past thousand years of Chinese rule in Northern Vietnam. A long history of Sino-Vietnamese conflicts followed, with repeated wars over the centuries. Though current relations are peaceful, numerous wars were fought between the two nations in the past, from the time of the Early Lê dynasty (10th century)[163] to the Sino-Vietnamese War from 1979 to 1989.

Shortly after the 1975 Vietnamese defeat of the United States in the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese government persecuted the Chinese community by confiscating property and businesses owned by overseas Chinese in Vietnam and expelling the ethnic Chinese minority into southern Chinese provinces.[164] In February 1976, Vietnam implemented registration programs in the south.[165]: 94 Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam were required to adopt Vietnamese citizenship or leave the country.[165]: 94 In early 1977, Vietnam implemented what it described as a purification policy in its border areas to keep Chinese border residents to the Chinese side of the border.[165]: 94–95 Following another discriminatory policy introduced in March 1978, a large number of Chinese fled from Vietnam to southern China.[165]: 95 China and Vietnam attempted to negotiate issues related to Vietnam's treatment of ethnic Chinese, but these negotiations failed to resolve the issues.[165]: 95 During the August 1978 Youyi Pass Incident, the Vietnamese army and police expelled 2,500 refugees across the order into China.[165]: 95 Vietnamese authorities beat and stabbed refugees during the incident, including 9 Chinese civilian border workers.[165]: 95 From 1978 to 1979, some 450,000 ethnic Chinese left Vietnam by boat (mainly former South Vietnam citizens fleeing the Vietcong) as refugees or were expelled across the land border with China.[166]

The 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War resulted in part from Vietnam's mistreatment of ethnic Chinese.[165]: 93 The conflict fueled racist discrimination against and consequent emigration by the country's ethnic Chinese population.These mass emigrations and deportations only stopped in 1989 following the Đổi mới reforms in Vietnam.[citation needed] The two countries' shared history includes territorial disputes, with conflict over the Paracel and Spratly Islands reaching a peak between 1979 and 1991.[167][168][169]

Anti-Chinese sentiments had spiked in 2007 after China formed an administration in the disputed islands,[168] in 2009 when the Vietnamese government allowed the Chinese aluminium manufacturer Chinalco the rights to mine for bauxite in the Central Highlands,[170][171][172] and when Vietnamese fishermen were detained by Chinese security forces while seeking refuge in the disputed territories.[173] In 2011, following a spat in which a Chinese Marine Surveillance ship damaged a Vietnamese geologic survey ship off the coast of Vietnam, some Vietnamese travel agencies boycotted Chinese destinations or refused to serve customers with Chinese citizenship.[174] Hundreds of people protested in front of the Chinese embassy in Hanoi and the Chinese consulate in Ho Chi Minh City against Chinese naval operations in the South China Sea before being dispersed by the police.[175] In May 2014, mass anti-Chinese protests against China moving an oil platform into disputed waters escalated into riots in which many Chinese factories and workers were targeted. In 2018, thousands of people nationwide protested against a proposed law regarding Special Economic Zones that would give foreign investors 99-year leases on Vietnamese land, fearing that it would be dominated by Chinese investors.[176]

According to journalist Daniel Gross, anti-Chinese sentiment is omnipresent in modern Vietnam, where "from school kids to government officials, China-bashing is very much in vogue." He reports that a majority of Vietnamese resent the import and usage of Chinese products, considering them of distinctly low status.[177] A 2013 book on varying host perceptions in global tourism has also referenced negativity from Vietnamese hosts towards Chinese tourists, where the latter were seen as "making a lot more requests, complaints and troubles than other tourists"; the views differed from the much more positive perceptions of young Tibetan hosts at Lhasa towards mainland Chinese visitors in 2011.[178]

In 2019, Chinese media was accused by the local press of appropriating or claiming Áo Dài, which angered many Vietnamese.[179][180]

South Asia

[edit]Afghanistan

[edit]According to The Diplomat in 2014, the Xinjiang conflict had increased anti-China sentiment in Afghanistan.[181] A 2020 Gallup International poll of 44 countries found that 46% of Afghans viewed China's foreign policy as destabilizing to the world, compared to 48% who viewed it as stabilizing.[182][183]

Nepal

[edit]Chinese outlet CGTN published a tweet about Mount Everest, calling it Mount Qomolangma in the Tibetan language and saying it was located in China's Tibet Autonomous Region, which caused displeasure from Nepalese and Indian Twitter users, who tweeted that China is trying to claim the mount from Nepal.[184] CGTN then corrected the tweet to say it was located on the China-Nepal border.[185]

Bhutan

[edit]The relationship between Bhutan and China has historically been tense and past events have led to anti-Chinese sentiment within the country. Notably, the Chinese government's destruction of Tibetan Buddhist institutions in Tibet in 1959 led to a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment in the country.[186] In 1960, the PRC published a map in A Brief History of China, depicting a sizable portion of Bhutan as "a pre-historical realm of China" and released a statement claiming the Bhutanese "form a united family in Tibet" and "they must once again be united and taught the communist doctrine". Bhutan responded by closing off its border, trade, and all diplomatic contacts with China. Bhutan and China have not established diplomatic relations.[187] Recent efforts between the two countries to improve relations have been hampered by India's strong influence on Bhutan.[188][189]

Sri Lanka

[edit]There were protests against allowing China to build a port and industrial zone, which will require the eviction of thousands of villagers around Hambantota.[190] Projects on the Hambantota port have led to fears among the local protestors that the area will become a "Chinese colony".[191] Armed government supporters clashed with protestors from the opposition that were led by Buddhist monks.[191]

India

[edit]During the Sino-Indian War, the Chinese faced hostile sentiment all over India. Chinese businesses were investigated for links to the Chinese government and many Chinese were interned in prisons in North India.[citation needed] The Indian government passed the Defence of India Act in December 1962,[192] permitting the "apprehension and detention in custody of any person hostile to the country." The broad language of the act allowed for the arrest of any person simply for having a Chinese surname or a Chinese spouse.[193] The Indian government incarcerated thousands of Chinese-Indians in an internment camp in Deoli, Rajasthan, where they were held for years without trial. The last internees were not released until 1967. Thousands more Chinese-Indians were forcibly deported or coerced to leave India. Nearly all internees had their properties sold off or looted.[192] Even after their release, the Chinese Indians faced many restrictions on their freedom. They could not travel freely until the mid-1990s.[192]

On 2014, India in conjunction with the Tibetan government-in-exile have called for a campaign to boycott Chinese goods due in part to the contested border disputes India has with China.[194][195]

The 2020 China–India skirmishes resulted in the deaths 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese soldiers, in hand-to-hand combat using improvised weapons.[196]

Following the skirmishes, a company from Jaipur, India developed an app named "Remove China Apps" and released it on the Google Play Store, gaining 5 million downloads in less than two weeks. It discouraged software dependence on China and promoted apps developed in India. Afterwards, people began uninstalling Chinese apps like SHAREit and CamScanner.[197]

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]

The Chinese population was active in political and social life in Australia. Community leaders protested against discriminatory legislation and attitudes, and despite the passing of the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, Chinese communities around Australia participated in parades and celebrations of Australia's Federation and the visit of the Duke and Duchess of York.

Although the Chinese communities in Australia were generally peaceful and industrious, resentment flared up against them because of their different customs and traditions. In the mid-19th century, terms such as "dirty, disease-ridden, [and] insect-like" were used in Australia and New Zealand to describe the Chinese.[198]

A poll tax was passed in Victoria in 1855 to restrict Chinese immigration. New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia followed suit. Such legislation did not distinguish between naturalised, British citizens, Australian-born, and Chinese-born individuals. The tax in Victoria and New South Wales was repealed in the 1860s.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the Growing trade union movement began a series of protests against foreign labour. Their arguments were that Asians and Chinese took jobs away from white men, worked for "substandard" wages, lowered working conditions, and refused unionisation.[199] Objections to these arguments came largely from wealthy land owners in rural areas.[199] It was argued that without Asiatics to work in the tropical areas of the Northern Territory and Queensland, the area would have to be abandoned.[200] Despite these objections to restricting immigration, between 1875 and 1888 all Australian colonies enacted legislation that excluded all further Chinese immigration.[200]

In 1888, following protests and strike actions, an inter-colonial conference agreed to reinstate and increase the severity of restrictions on Chinese immigration. This provided the basis for the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act and the seed for the White Australia Policy, which although relaxed over time, was not fully abandoned until the early 1970s.

The Chifley government's Darwin Lands Acquisition Act 1945 compulsorily acquired 53 acres (21 ha) of land owned by Chinese-Australians in Darwin, the capital of the Northern Territory, leading to the end of the local Chinatown. Two years earlier, the territory's administrator Aubrey Abbott had written to Joseph Carrodus, secretary of the Department of the Interior, proposing a combination of compulsory acquisition and conversion of the land to leasehold in order to effect "the elimination of undesirable elements which Darwin has suffered from far too much in the past" and stated that he hoped to "entirely prevent the Chinese quarter forming again". He further observed that "if land is acquired from the former Chinese residents there is really no need for them to return as they have no other assets". The territory's civilian population had mostly been evacuated during the war and the former Chinatown residents returned to find their homes and businesses reduced to rubble.[201]

A number of cases have been reported, related to sinophobia in the country.[202] Recently, in February 2013, a Chinese football team had reported about the abuses and racism they suffered on Australia Day.[11]

There have been a spate of racist anti-Chinese graffiti and posters in universities across Melbourne and Sydney which host a large number of Chinese students. In July and August 2017, hate-filled posters were plastered around Monash University and University of Melbourne which said, in Mandarin, that Chinese students were not allowed to enter the premises, or else they would face deportation, while a "kill Chinese" graffiti, decorated with swastikas was found at University of Sydney.[203][204] The Antipodean Resistance, a white supremacist group that identifies itself as pro-Nazi, claimed responsibility for the posters on Twitter. The group's website contains anti-Chinese slurs and Nazi imagery.[205]

New Zealand

[edit]In the 1800s, Chinese citizens were encouraged to immigrate to New Zealand because they were needed to fulfill agricultural jobs during a time of white labor shortage. The arrival of foreign laborers was met with hostility and the formation of anti-Chinese immigrant groups, such as the Anti-Chinese League, the Anti-Asiatic League, the Anti-Chinese Association, and the White New Zealand League. Official discrimination began with the Chinese Immigrants Act of 1881, limiting Chinese emigration to New Zealand and excluding Chinese citizens from major jobs. Anti-Chinese sentiment had declined by the mid-20th century, however it has recently been inflamed by the perception that Chinese immigrants have driven up housing prices.[206] Today, anti-Chinese sentiment in New Zealand mainly concerns the issue of housing prices.[206] K. Emma Ng reported that "One in two New Zealanders feel the recent arrival of Asian migrants is changing the country in undesirable ways." There are considerable numbers of Asians who express anti-Chinese sentiment in New Zealand, which Ng attributes to internalized self hatred.[206]

Attitudes on Chinese in New Zealand are suggested to be fairly negative, with some Chinese still considered to be less respected people in the country.[207]

Papua New Guinea

[edit]In May 2009, during the Papua New Guinea riots, Chinese-owned businesses were looted by gangs in the capital city Port Moresby, amid simmering anti-Chinese sentiment reported in the country.[208] There are fears that these riots will force many Chinese business owners and entrepreneurs to leave the South Pacific country, which would invariably lead to further damage on an impoverished economy that had a 80% unemployment rate.[208] Thousands of people were reportedly involved in the riots.[209]

Tonga

[edit]In 2000, Tongan noble Tu'ivakano of Nukunuku banned Chinese stores from his Nukunuku District in Tonga. This followed complaints from other shopkeepers regarding competition from local Chinese.[210]

In 2006, rioters damaged shops owned by Chinese-Tongans in Nukuʻalofa.[211][212]

Solomon Islands

[edit]In 2006, Honiara's Chinatown suffered damage when it was looted and burned by rioters following a contested election. Ethnic Chinese businessmen were falsely blamed for bribing members of the Solomon Islands' Parliament. The government of Taiwan was the one that supported the then-current government of the Solomon Islands. The Chinese businessmen were mainly small traders from mainland China and had no interest in local politics.[211]

Western Asia

[edit]Israel

[edit]Israel and China have a stable relationship, and a 2018 survey suggested that a significant percentage of the Israeli population have a positive view of Chinese culture and people.[213] This is historically preceded by Chinese support for Jewish refugees fleeing from Europe amidst World War II.[214] Within China, Jews gained praise for their successful integration, with a number of Jewish refugees advising Mao's government and leading developments in revolutionary China's health service and infrastructure.[215][216][217]

However, these close relations between the early Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the small Jewish-Chinese community have been hampered in recent years under the administration of CCP general secretary Xi Jinping and rise of nationalist sentiment in China, with Jews monitored since 2016, an occurrence reported widely in Israeli media.[218][219] This has led to some Sinophobic sentiments in Israel, with Israeli nationalists viewing China a despotic and authoritarian regime, given the ongoing repression of Jews in China.[218][failed verification]

Turkey

[edit]On July 4, 2015, a group of around 2,000 Turkish ultra-nationalists from the Grey Wolves linked to Turkey's MHP (Nationalist Movement Party) protesting against China's alleged fasting ban in Xinjiang mistakenly attacked South Korean tourists in Istanbul,[220][221] which led to China issuing a travel warning to its citizens traveling to Turkey.[222] Devlet Bahçeli, a leader from MHP, said that the attacks by MHP affiliated Turkish youth on South Korean tourists was "understandable", telling the Turkish newspaper Hurriyet that: "What feature differentiates a Korean from a Chinese? They see that they both have slanted eyes. How can they tell the difference?".[223]

A Uyghur employee at a Chinese restaurant was attacked in 2015 by the Turkish Grey Wolves-linked protesters.[224] Attacks on other Chinese nationals have been reported.[225]

According to a November 2018 INR poll, 46% of Turks view China favourably, up from less than 20% in 2015. A further 62% thought that it is important to have a strong trade relationship with China.[226]

Europe

[edit]

China has figured in Western imagination in a number of different ways as being a very large civilization existing for many centuries with a very large population; however the rise of the People's Republic of China after the Chinese Civil War has dramatically changed the perception of China from a relatively positive light to negative because of anti-communism in the West, and reports of human rights abuses from China.

Anti-Chinese sentiment became more common as China was becoming a major source of immigrants for the west (including the American West).[12] Numerous Chinese immigrants to North America were attracted by wages offered by large railway companies in the late 19th century as the companies built the transcontinental railroads.

Anti-Chinese policies persisted in the 20th century in the English-speaking world, including the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, anti-Chinese zoning laws and restrictive covenants, the policies of Richard Seddon, and the White Australia policy

Czech Republic

[edit]Anti-Chinese sentiment has experienced a new growth due to closer ties between the Czech Republic and Taiwan and led to a deterioration of the Czech Republic's relations with China.[227][228] Czech politicians have demanded China to replace its ambassador and criticizing the Chinese government for its alleged threats against the Czech Republic, further worsening China's perception in the country.[229]

France

[edit]In France, there has been a long history of systemic racism towards the Chinese population, with many people stereotyping them as easy targets for crime.[230] As a result, France's ethnic Chinese population have been common victims of racism and crime, which include assaults, robbery, and murder; it is common for Chinese business owners to have their businesses robbed and destroyed.[230] There have been rising incidents of anti-Chinese racism in France; many Chinese, including French celebrity Frederic Chau, want more support from the French government.[231] In September 2016, at least 15,000 Chinese participated in an anti-Asian racism protest in Paris.[230]

French farmers protested after a Chinese investor purchased 2,700 hectares of agricultural land in France.[232] A 2018 survey by Institut Montaigne has suggested that Chinese investments in France are viewed more negatively than Chinese tourism to the country, with 50% of respondents holding negative views of the former.[233] 43% of the French see China as an economic threat, an opinion that is common among older and right-wing people, and 40% of French people view China as a technological threat.[233]

It was reported in 2017 that there was some negativity among Parisians towards Chinese visitors,[234] but other surveys have suggested that they are not viewed worse than a number of other groups.[235][236][237]

Germany

[edit]In 2016, Günther Oettinger, the former European Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society, called Chinese people derogatory names, including "sly dogs", in a speech to executives in Hamburg and had refused to apologize for several days.[citation needed] Two surveys have suggested that a percentage of Germans hold negative views towards Chinese travellers, although it is not as bad as a few other groups.[238][239][240]

Italy

[edit]Although historical relations between two were friendly and even Marco Polo paid a visit to China, during the Boxer Rebellion, Italy was part of Eight-Nation Alliance against the rebellion, thus this had stemmed anti-Chinese sentiment in Italy.[241] Italian troops looted, burnt, and stole a lot of Chinese goods to Italy, many are still being displayed in Italian museums.[242]

In 2010, in the Italian town of Prato, it was reported that many Chinese people were working in sweatshop-like conditions that broke European laws and that many Chinese-owned businesses don't pay taxes.[243] Textile products produced by Chinese-owned businesses in Italy are labeled as 'Made in Italy', but some of the businesses engaged in practices that reduce cost and increase output to the point where locally owned businesses can't compete with. As a result of these practices, the 2009 municipal elections led the local population to vote for the Lega Nord, a party known for its anti-immigrant stance.[243]

Portugal

[edit]In the 16th century, increasing sea trades between Europe to China had led Portuguese merchants to China, however Portuguese military ambitions for power and its fear of China's interventions and brutality had led to the growth of sinophobia in Portugal. Galiote Pereira, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary who was imprisoned by Chinese authorities, claimed China's juridical treatment known as bastinado was so horrible as it hit on human flesh, becoming the source of fundamental anti-Chinese sentiment later; as well as brutality, the cruelty of China and Chinese tyranny.[244] With the Ming dynasty's brutal reactions on Portuguese merchants following the conquest of Malacca,[245] sinophobia became widespread in Portugal, and widely practiced until the First Opium War, which the Qing dynasty was forced to cede Macao to Portugal.[246][note 2]

Russia

[edit]After the Sino-Soviet split the Soviet Union produced propaganda which depicted the PRC and the Chinese people as enemies. Soviet propaganda specifically framed the PRC as an enemy of Islam and all Turkic peoples. These phobias have been inherited by the post-Soviet states in Central Asia.[247]

Although Russia had inherited a long-standing dispute over territory with China over Siberia and the Russian Far East with the breakup of the Soviet Union, these disputes were formerly resolved in 2004. Russia and China no longer have territorial disputes and China does not claim land in Russia; however, there has also been a perceived fear of a demographic takeover by Chinese immigrants in sparsely populated Russian areas.[248][249] Both nations have become increasingly friendlier however, in the aftermath of the 1999 US bombing of Serbia, which the Chinese embassy was struck with a bomb, and have become increasingly united in foreign policy regarding perceived western antipathy.[250][251]

A 2019 survey of online Russians has suggested that in terms of sincerity, trustfulness, and warmth, the Chinese are not viewed especially negatively or positively compared to the many other nationalities and ethnic groups in the study.[252][253] An October 2020 poll from the Central European Institute of Asian Studies[254] found that although China was perceived positively by 59.5% of Russian respondents (which was higher than for the other 11 regions asked), 57% of respondents regarded Chinese enterprises in the Russian far east to varying degrees as a threat to the local environment.[255]

Spain

[edit]Spain first issued anti-Chinese legislation when Limahong, a Chinese pirate, attacked Spanish settlements in the Philippines. One of his famous actions was a failed invasion of Manila in 1574, which he launched with the support of Chinese and Moro pirates.[256] The Spanish conquistadors massacred the Chinese or expelled them from Manila several times, notably the autumn 1603 massacre of Chinese in Manila, and the reasons for this uprising remain unclear. Its motives range from the desire of the Chinese to dominate Manila, to their desire to abort the Spaniards' moves which seemed to lead to their elimination. The Spaniards quelled the rebellion and massacred around 20,000 Chinese. The Chinese responded by fleeing to the Sulu Sultanate and supporting the Moro Muslims in their war against the Spanish. The Chinese supplied the Moros with weapons and joined them in directly fighting against the Spanish during the Spanish–Moro conflict. Spain also upheld a plan to conquer China, but it never materialized.[257]

A Central European Institute of Asian Studies poll in 2020[254] found that although Spaniards had worsening views of China amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, it did not apply to Chinese citizens where most respondents reported positive views of Chinese tourists, students, and the general community in Spain.[258]

Sweden

[edit]In 2018, a family of Chinese tourists was removed from a hostel in Stockholm, which led to a diplomatic spat between China and Sweden. China accused the Swedish police of maltreatment as Stockholm's chief prosecutor chose not to investigate the incident.[259] A comedy skit later aired on Svenska Nyheter mocking the tourists and playing on racial stereotypes of Chinese people.[260][261] After the producers uploaded the skit to Youku, it drew anger and accusations of racism on Chinese social media,[262] the latter of which was also echoed in a letter to the editor from a Swedish-Chinese scholar[263] to Dagens Nyheter.[264] Chinese citizens were called on to boycott Sweden.[265] The next year, Jesper Rönndahl, the host of the skit, was honoured by Swedish newspaper Kvällsposten as "Scanian of the Year".[266]

Relations further worsened after the reported kidnap and arrest of China-born Swedish citizen and bookseller Gui Minhai by Chinese authorities, which led to three Swedish opposition parties calling for the expulsion of China's ambassador to Sweden, Gui Congyou, who had been accused of threatening several Swedish media outlets.[267][268] Several Swedish cities cut ties with China's cities in February 2020 amid deteriorating relations.[269] In May 2020, Sweden decided to shut down all Confucius Institutes in the country, citing the Chinese government's meddling in education affairs.[270] Some Chinese in Sweden have also reported increased stigmatisation during the COVID-19 pandemic.[271] A 2021 YouGov poll had 77% of Swedish respondents expressing an unfavourable view of China, with no other country more negatively viewed in Sweden except for Iran and Saudi Arabia.[272]

Ukraine

[edit]During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the pro-Russian Chinese government media stance along with reports of chauvinistic comments about Ukrainian women and pro-Russian sentiment by some Chinese netizens led to the fueling of anti-Chinese sentiment in Ukraine. In response, the Embassy of China in Kyiv, which originally encouraged citizens to display Chinese flags on their cars for protection while leaving Ukraine, quickly urged them not to identify themselves or sport any signs of national identity.[273][274] In a 2023 Razumkov Centre opinion poll 60% of Ukrainians had a negative view of China[275] - up from 14% in 2019.[276]

United Kingdom

[edit]15% of ethnic Chinese reported racial harassment in 2016, which was the highest percentage out of all ethnic minorities in the UK.[277] The Chinese community has been victims of racially-aggravated attacks and murders, verbal accounts of racism, and vandalism. There is also a lack of reporting on anti-Chinese discrimination in the UK, notably violence against Chinese Britons.[278]

The ethnic slur "chink" has been used against the Chinese community; Dave Whelan, the former owner of Wigan Athletic, was fined £50,000 and suspended for six weeks by The Football Association after using the term in an interview; Kerry Smith resigned as an election candidate after it was reported he used similar language.[278]

Professor Gary Craig from Durham University carried out research about the Chinese population in the UK, and concluded that hate crimes against the Chinese community are getting worse, adding that British Chinese people experience "perhaps even higher levels of racial violence or harassment than those experienced by any other minority group but that the true extent to their victimization is often overlooked because victims were unwilling to report it."[278] Official police victim statistics put Chinese people in a group that includes other ethnicities, making it difficult to understand the extent of the crimes against the Chinese community.[278]

Americas

[edit]Argentina

[edit]Since the 1990s there has been a large wave of immigration of Chinese citizens, mainly from Fujian province. The main business in which the Chinese are dedicated in Argentina is grocery stores and on several occasions they have been accused of unplugging the refrigerators of fresh products during the night to pay cheaper electricity bills. During the social outbreak of 2001, derived from the economic crisis of that year in Argentina, several Chinese-owned supermarkets were attacked.[279]

Brazil

[edit]Chinese investments in Brazil have been largely influenced by this[clarification needed] negative impression.[280]

Canada

[edit]In the 1850s, sizable numbers of Chinese immigrants came to British Columbia during the gold rush; the region was known to them as Gold Mountain. Starting in 1858, Chinese "coolies" were brought to Canada to work in the mines and on the Canadian Pacific Railway. However, they were denied by law the rights of citizenship, including the right to vote, and in the 1880s, "head taxes" were implemented to curtail immigration from China. In 1907, a riot in Vancouver targeted Chinese and Japanese-owned businesses. In 1923, the federal government banned Chinese immigration outright,[32]: 31 passing the Chinese Immigration Act, commonly known as the Exclusion Act, prohibiting further Chinese immigration except under "special circumstances". The Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947, the same year in which Chinese Canadians were given the right to vote. Restrictions would continue to exist on immigration from Asia until 1967 when all racial restrictions on immigration to Canada were repealed, and Canada adopted the current points-based immigration system. On June 22, 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology and compensation only for the head tax once paid by Chinese immigrants.[281] Survivors or their spouses were paid approximately CA$20,000 in compensation.[282]

Anti-Chinese sentiment in Canada has been fueled by allegations of extreme real estate price distortion resulting from Chinese demand, purportedly forcing locals out of the market.[283]

Mexico

[edit]Anti-Chinese sentiment was first recorded in Mexico in 1880s. Similar to most Western countries at the time, Chinese immigration and its large business involvement have always been a fear for native Mexicans. Violence against Chinese occurred such as in Sonora, Baja California and Coahuila, the most notable was the Torreón massacre.[284]

Peru

[edit]Peru was a popular destination for Chinese slaves in the 19th century, as part of the wider blackbirding phenomenon, due to the need in Peru for a military and laborer workforce. However, relations between Chinese workers and Peruvian owners have been tense, due to the mistreatment of Chinese laborers and anti-Chinese discrimination in Peru.[33]

Due to the Chinese support for Chile throughout the War of the Pacific, relations between Peruvians and Chinese became increasingly tenser in the aftermath. After the war, armed indigenous peasants sacked and occupied haciendas of landed elite criollo "collaborationists" in the central Sierra – the majority of them were of ethnic Chinese, while indigenous and mestizo Peruvians murdered Chinese shopkeepers in Lima; in response to Chinese coolies revolted and even joined the Chilean Army.[285][286] Even in the 20th century, the memory of Chinese support for Chile was so deep that Manuel A. Odría, once dictator of Peru, issued a ban against Chinese immigration as a punishment for their betrayal.[287]

United States

[edit]

Starting with the California Gold Rush in the 19th century, the United States—particularly the West Coast states—imported large numbers of Chinese migrant laborers. Employers believed that the Chinese were "reliable" workers who would continue working, without complaint, even under harsh conditions.[288] The migrant workers encountered considerable prejudice in the United States, especially among the people who occupied the lower layers of white society, because Chinese "coolies" were used as scapegoats for depressed wage levels by politicians and labor leaders.[289] Cases of physical assaults on the Chinese include the Chinese massacre of 1871 in Los Angeles. The 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel in New York, for which a Chinese person was suspected, was blamed on the Chinese in general and it immediately led to physical violence against them. "The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States."[290]

The emerging American trade unions, under such leaders as Samuel Gompers, also took an outspoken anti-Chinese position,[291] regarding Chinese laborers as competitors to white laborers. Only with the emergence of the international trade union, IWW, did trade unionists start to accept Chinese workers as part of the American working class.[292]

In the 1870s and 1880s, various legal discriminatory measures were taken against the Chinese. These laws, in particular, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, were aimed at restricting further immigration from China.[31] although the laws were later repealed by the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943. In particular, even in his lone dissent against Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), then-Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote of the Chinese as: "a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race."[293]

In April 2008, CNN's Jack Cafferty remarked: "We continue to import their junk with the lead paint on them and the poisoned pet food [...] So I think our relationship with China has certainly changed. I think they're basically the same bunch of goons and thugs they've been for the last 50 years." At least 1,500 Chinese Americans protested outside CNN's Hollywood offices in response while a similar protest took place at CNN headquarters in Atlanta.[294][295]

In the 2010 United States elections, a significant number[296] of negative advertisements from both major political parties focused on a candidates' alleged support for free trade with China which were criticized by Jeff Yang for promoting anti-Chinese xenophobia.[297] Some of the stock images that accompanied ominous voiceovers about China were actually of Chinatown, San Francisco.[297] These advertisements included one produced by Citizens Against Government Waste called "Chinese Professor", which portrayed a 2030 conquest of the West by China and an ad by Congressman Zack Space attacking his opponent for supporting free trade agreements like NAFTA, which the ad had claimed caused jobs to be outsourced to China.[298]

In October 2013, a child actor on Jimmy Kimmel Live! jokingly suggested in a skit that the U.S. could solve its debt problems by "kill[ing] everyone in China."[299][300]

Donald Trump, the 45th President of the United States, was accused of promoting sinophobia throughout his campaign for the Presidency in 2016.[301][302] and it was followed by his imposition of trade tariffs on Chinese goods, which was seen as a declaration of a trade war and another anti-Chinese act.[303] The deterioration of relations has led to a spike in anti-Chinese sentiment in the US.[304][305]

According to a Pew Research Center poll which was conducted in April 2022, 82% of Americans have unfavorable opinions of China, including 40% who have very unfavorable views of the country.[306] In recent years, however, Americans increasingly see China as a competitor, not as an enemy.[306] 62% view China as a competitor and 25% an enemy, with 10% seeing China as a partner.[306] In January 2022, only 54% chose competitor and 35% said enemy, almost the same distribution as the prior year.[306]

It has been noted that there is a negative bias in American reporting on China.[307][295][308] Many Americans, including American-born Chinese, have continuously held prejudices toward mainland Chinese people[309][310] which include perceived rudeness and unwillingness to stand in line,[311][312] even though there are sources that have reported contrary to those stereotypes.[313][314][315][316][317][excessive citations] However, the results of a survey which was conducted in 2019 have revealed that some Americans still hold positive views of Chinese visitors to the US.[318]

A Pew Research poll which was conducted in the US in March 2021 revealed that 55% of respondents supported the imposition of limits on the number of Chinese students who are allowed to study in the country.[319]

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of laws which explicitly discriminate against Chinese people in the United States. For example, in 2023, Florida introduced a law which bans Chinese nationals from owning property in the state, a law that has been compared to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.[320]

Africa

[edit]Anti-Chinese populism has been an emerging presence in some African countries.[321] There have been reported incidents of Chinese workers and business-owners being attacked by locals in some parts of the continent.[322][323] Following reports of evictions, discrimination and other mistreatment of Africans in Guangzhou during the COVID-19 pandemic,[324] a group of diplomats from different African countries wrote a letter to express their displeasure over the treatment of their citizens.[325]

Kenya

[edit]In areas where Chinese contractors are building infrastructure, there has been an increase in Anti-Chinese sentiment among Kenyan youths. Kenyan youths have attacked Chinese contract workers, and accused them of denying local workers of job opportunities.[326][better source needed]

Ghana

[edit]A sixteen-year-old illegal Chinese miner was shot in 2012 while trying to escape arrest, an event that led Chinese miners to subsequently begin arming themselves with rifles.[327]

Zambia

[edit]In 2006, Chinese businesses were targeted in riots by angry crowds after the electoral defeat of the anti-China Patriotic Front. According to Rohit Negi of Ambedkar University Delhi, "the popular opposition to China in Zambia is linked to a surge in economic nationalism and new challenges to the neoliberal orthodoxy."[328] Zambia's ruling government accused the opposition of fueling xenophobic attacks against Chinese nationals.[329] A 2016 study from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology suggested though that locals held more nuanced views of Chinese people, ranking them not as highly as Caucasians, but also less negatively than Lebanese, and to some extent, Indian people.[330]

South Africa

[edit]In 2016, the South African government planned to offer Mandarin as an additional optional language along with German, Serbian, Italian, Latin, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil, Telugu and Urdu.[331] However, the teachers union in South Africa accused the government of surrendering to Chinese imperialism.[331] As of 2017, there were 53 schools that offered Mandarin in the country.[332]

The Chinese have been victims of robberies and hijackings, and as the South African economy worsens, the hostility towards the Chinese and other foreigners has increased.[333]

Depiction of China and Chinese in media

[edit]Depictions of China and Chinese in Anglophone media have been a somewhat underreported subject in general, but most are mainly negative coverage.[295] In 2016, Hong Kong's L. K. Cheah said to South China Morning Post that Western journalists who regard China's motives with suspicion and cynicism cherry-pick facts based on a biased view, and the misinformation that they produce as a result is unhelpful and sympathetic of the resentment against China.[334]

According to China Daily, a nationalist daily newspaper in China, Hollywood is accused of negative portrayals of Chinese in movies, such as bandits, thugs, criminals, gangsters, dangerous, cold-blooded, weak, and cruel;[335] while American, as well as European, or Asian characters in general, are depicted as saviors. Even anti-Chinese whitewashing in film is common. Matt Damon, the American actor who appeared in The Great Wall, has also faced criticism that he had participated in "whitewashing" through his involvement in the historical epic and Hollywood-Chinese co-produced movie, which he denied.[336]

In practice, anti-Chinese political rhetoric usually puts emphasis on highlighting policies and alleged practices of the Chinese government that are criticised internally – corruption, human rights issues, unfair trade, censorship, violence, military expansionism, political interferences, and historical imperialist legacies. It is often in line with independent media opposing the Chinese government in mainland China as well as in the Special Administrative Regions of China, Hong Kong, and Macau.[citation needed] In defence of this rhetoric, some sources critical of the Chinese government claim that it is Chinese state-owned media and administration who attempt to discredit the "neutral" criticism by generalizing it into indiscriminate accusations of the whole Chinese population, and targeting those who criticize the regime[337] - or sinophobia.[338][339][340] Some have argued, however, that the Western media, similar to Russia's depictions, does not make enough distinction between CPC's regime and China and the Chinese, thus effectively vilifying the whole nation.[341]

Impact on Chinese student populations

[edit]On occasion, Chinese students in the West are stereotyped as lacking in critical thinking skills and prone to plagiarism, or as harming the educational environment.[342]

Historical acts of Sinophobic violence

[edit]List of non-Chinese "sinophobia-led" acts of violence against ethnic Chinese:

Australia

[edit]Canada

[edit]Mexico

[edit]Mongolia

[edit]- Mongol conquest of China

- Deportation of Chinese people to China in the 1960's

- Attacks against Chinese by the Tsagaan Khas

Indonesia

[edit]- 1740 Batavia massacre

- 1918 Kudus riot

- Mergosono massacre

- Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66

- 1967 Mangkuk Merah Tragedy

- 1980 Jawa Tengah Racial Riot

- Situbondo Riot

- Banjarmasin riot of May 1997

- May 1998 riots of Indonesia

- November 2016 Jakarta protests

Malaysia

[edit]Japan

[edit]

By Koreans

[edit]- Wanpaoshan Incident, on July 1, 1931

United States

[edit]- Chinese massacre of 1871

- Rock Springs massacre

- Issaquah riot of 1885

- Tacoma riot of 1885

- Seattle riot of 1886

- Hells Canyon Massacre

- Anti-Chinese violence in California

- Denver Riot of 1880

- Killing of Vincent Chin

Vietnam

[edit]Derogatory terms

[edit]There are a variety of derogatory terms for China and Chinese people. Many of these terms are racist. However, these terms do not necessarily refer to the Chinese ethnicity as a whole; they can also refer to specific policies, or specific time periods in history.

In English

[edit]- Eh Tiong (阿中) – refers specifically to Chinese nationals. Primarily used in Singapore to differentiate between the Singaporeans of Chinese heritage and Chinese nationals. From Hokkien 中, an abbreviation of 中國 ("China"). Considered offensive.

- Cheena – same usage as 'Eh Tiong' in Singapore. Compare Shina (支纳).

- Chinaman – the term Chinaman is noted as offensive by modern dictionaries, dictionaries of slurs and euphemisms, and guidelines for racial harassment.

- Ching chong – Used to mock people of Chinese descent and the Chinese language, or other East and Southeast Asian-looking people in general.

- Ching chang chong – same usage as 'ching chong'.

- Chink – a racial slur referring to a person of Chinese ethnicity, but could be directed towards anyone of East and Southeast Asian descent in general.

- Chinky – the name "Chinky" is the adjectival form of Chink and, like Chink, is an ethnic slur for Chinese occasionally directed towards other East and Southeast Asian people.

- Chonky – refers to a person of Chinese heritage with white attributes whether being a personality aspect or physical aspect.[344][345]

- Coolie – means laborer in reference to Chinese manual workers in the 19th and early 20th century.

- Slope – used to mock people of Chinese descent and the sloping shape of their skull, or other East Asians. Used commonly during the Vietnam War.

- Chicom – used to refer to a Communist Chinese.

- Panface – used to mock the flat facial features of the Chinese and other people of East and Southeast Asian descent.

- Lingling – used to call someone of Chinese descent in the West.

- Chinazi – a recent anti-Chinese sentiment which compares China to Nazi Germany, combining the words "China" and "Nazi". First published by Chinese dissident Yu Jie,[346][347] it became frequently used during Hong Kong protests against the Chinese government.[348][349]

- Made in China – used to mock low-quality products, even to dismiss high-quality products that happen to be made in China. Term can extend to other pejoratively perceived aspects of the country.[124]

- Wumao - used in online communities to accuse users of being government-sponsored propagandists, referring to the 50 Cent Party.

In Filipino