American Graffiti: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by All graffiti all the time (talk) to last version by XLinkBot |

Why do you keep removeing my external link? American Graffiti fans will like the link! |

||

| Line 214: | Line 214: | ||

* [http://www.geocities.com/kippullman Kip Pullman's ''American Graffiti'' Web Page] |

* [http://www.geocities.com/kippullman Kip Pullman's ''American Graffiti'' Web Page] |

||

* [http://www.americangraffiti.net The City of Petaluma's Salute to ''American Graffiti''] |

* [http://www.americangraffiti.net The City of Petaluma's Salute to ''American Graffiti''] |

||

* [http://www.dahuipresents.blogspot.com da Hui Presents All Graffiti All The Time] |

|||

<!--spacing, please do not remove--> |

<!--spacing, please do not remove--> |

||

Revision as of 01:51, 29 April 2009

| American Graffiti | |

|---|---|

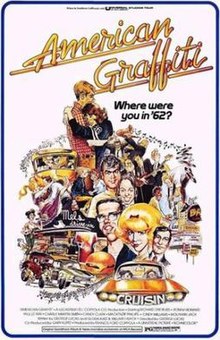

film poster by Mort Drucker | |

| Directed by | George Lucas |

| Written by | George Lucas Gloria Katz Willard Huyck |

| Produced by | Francis Ford Coppola Gary Kurtz |

| Starring | Richard Dreyfuss Ron Howard Paul Le Mat Charles Martin Smith Candy Clark Mackenzie Phillips Cindy Williams Wolfman Jack |

| Cinematography | Ron Eveslage Jan D'Alquen |

| Edited by | George Lucas (uncredited) Verna Fields Marcia Lucas |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates | August 1, 1973 (US premiere) August 11, 1973 (US general) |

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$1.25 million[1] |

| Box office | $115 million (North America) |

American Graffiti is a 1973 period coming of age film directed by George Lucas, and written by Lucas, Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck. The film stars Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, Paul Le Mat, Charles Martin Smith, Candy Clark, Mackenzie Phillips, Cindy Williams, Suzanne Somers, and Wolfman Jack and features Harrison Ford. Set in 1962 Modesto, California, American Graffiti shows the adventures of a group of teenagers during a night of cruising around town and listening to pirate radio personality Wolfman Jack.

George Lucas began developing the film shortly after the release of his THX 1138 in 1971, while at the same time developing an "untitled science fiction space opera".[2][3] American Graffiti was initially funded by United Artists, but after creative differences arose with the studio, Lucas decided to work with Universal Pictures instead.[4] Filming started in the summer of 1972 at San Rafael, California, but the production was kicked out of the town after only one night's filming. (The majority of the movie was filmed during the evening, night, and dawn hours.) The crew relocated to Petaluma, California where filming resumed over the next four weeks. Although Universal interfered little with production, the studio did object to the film's title of American Graffiti, recommending Lucas change it to Another Slow Night in Modesto among many others.[5]

The editing of American Graffiti was strenuous: the first cut was roughly 210 minutes long, and the final cut was released at 112 minutes.[6] To this day the location of the other 100 minutes of footage remains unknown. The film received positive reviews and was a box office success (recouping 92 times its budget with its North American financial take).[1][7][8] The film was nominated for five different categories at the 46th Academy Awards, and in 1995 American Graffiti was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress, and was added to the National Film Registry for preservation.[9][10]

Plot

The story is presented in a series of vignettes focused on the four main characters—Curt Henderson (Richard Dreyfuss), Steve Bolander (Ron Howard), John Milner (Paul Le Mat), and Terry "The Toad" Fields (Charles Martin Smith). The four meet in the Mel's Drive-In parking lot at sunset as a car radio plays a rock and roll station. Steve and Curt are preparing to leave town to attend college in the East, and this is the last night they will spend with their friends. Despite receiving a scholarship from the local Moose Lodge, Curt is reluctant to head off for the unknown, but Steve is eager to get out of Modesto. His girlfriend Laurie (Cindy Williams), Curt's younger sister, is unsure of his leaving, to which he suggests they see other people while he is away to "strengthen" their relationship.

Steve and Curt are off to the freshman Sock Hop, but John goes off to cruise the streets in his yellow deuce coupe. Steve lets Terry have his 1958 Chevy Impala for the evening and while he will be away at college. While cruising down 10th street, Curt sees a beautiful blonde girl (Suzanne Somers) in a white 1956 Ford Thunderbird. She mouths "I love you" before disappearing down the street. After leaving the hop, Curt is coerced into riding with a gang of greasers who call themselves "The Pharaohs." He learns that disc jockey Wolfman Jack broadcasts from just outside of town (despite rumors to the contrary), and inside the dark, eerie radio station Curt encounters a bearded man he assumes to be the manager. Curt hands the manager a message for the "Blonde in T-Bird" to call him or meet him. As he walks away, Curt hears the voice of the Wolfman and realizes he had been speaking with him.

The other three story lines involve friendships, breakups and reunions, and their stories intertwine until Toad and Steve end up on "Paradise Road" to watch John race against Bob Falfa (Harrison Ford), with Laurie as Falfa's passenger. Within seconds, it is all over: Falfa's car apparently blows a tire and plunges into a ditch. Steve and John run over to the wreck, and a dazed Bob and Laurie stagger out of the car before it explodes. Distraught, Laurie grips Steve tightly and tells him not to leave her. He assures her that he has decided to not go away to the East after all.

The next morning, the sound of a phone ringing in a telephone booth wakes Curt. He answers; it is the mysterious blonde girl. She tells him she might see him cruising tonight, but Curt replies that's not possible, because he will be leaving town. At the airfield, Curt says goodbye to his parents, his sister, and his friends. While saying goodbye to Laurie, he asks Steve to join him. Steve tells him he is staying in town and enrolling in junior college instead. As the plane takes off, Curt gazes out of the window at the town and the life he is leaving behind. As he watches, he sees the white Ford Thunderbird, which belongs to the mysterious blonde. Curt smiles, and as the movie ends but prior to the closing credits, the fates of the main characters are depicted: John was killed by a drunk driver in December 1964; Steve became an insurance agent in Modesto, California; Terry "The Toad" was reported missing in action in December 1965 near An Loc, Vietnam; Curt was living in Canada as a writer.

Development

United Artists

| "There's no message or long speech, but you know that, when the story ends, America underwent a drastic change. The early 1960s were the end of an era. It hit us all very hard." |

| — George Lucas on the premise of the storyline[11] |

George Lucas had pitched American Graffiti unsuccessfully to various Hollywood film studios and production companies in 1971,[2] with a five-page story treatment and less than $500 to his name. Taking his inspiration from Federico Fellini's I Vitelloni (1953),[12] Lucas felt "it was time to make a movie where people felt better coming out of the theater than when they went in".[13] He was quickly turned down by 20th Century Fox, Paramount Pictures, and American International Pictures.[13]

Alan Trustman was intrigued by the idea and was impressed with Lucas' work on THX 1138 (1971), offering Lucas the chance to direct Lady Ice (1973). Lucas turned down a salary of $150,000 and a large percentage of the profits of the box office gross, determined to pursue his own projects, one of them being an "untitled space opera produced in the style of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers (1939)".[2] He originally hoped to direct a new version of Flash Gordon and met with King Features for film licenses, although they coincidentally wished for Fellini to direct.[2] Lucas was also developing early concepts of Apocalypse Now (1979) and Radioland Murders (1994).[11]

THX 1138 was selected at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1971 ,, where Lucas met David Picker, president of United Artists. Intrigued with both American Graffiti and Lucas' untitled science fiction film, Picker gave Lucas $10,000 to develop a script. Lucas contacted Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck to write the script, but they were too busy with Messiah of Evil (1972). However, Katz and Huyck were willing to write the story with Lucas.[12] Lucas found Richard Walter, a former colleague at USC School of Cinematic Arts.[14] Walter was flattered, but instead tried to pitch a screenplay called Barry and the Persuasions, a story of East Coast teenagers in the late 1950s. Lucas held firm; his was a story about West Coast teenagers in the early 1960s. Lucas gave Walter the $10,000 to translate his story treatment into a script, but Lucas was dismayed when he returned and read the result, which Lucas recalls was written in the style of a "Hot Rods to Hell exploitation film"[14] and was too "overtly sexual."[13] Lucas explained, "It was very fantasy-like, with playing chicken and things that kids didn't really do. I wanted something that was more like the way I grew up."[15] Walter responded, "I'm a Jew from New York. What do I know from Modesto?" We didn't have cars. We rode the subway, or bicycles."[16]

Walter rewrote the script, but it soon became clear that his ideas were out of sync with Lucas' intentions. After paying Walter, Lucas had exhausted his development fund, and he had to now write the script himself. Lucas wanted to show Picker a screenplay as soon as possible, writing his first draft in just three weeks.[14] Drawing upon his large collection of vintage 45 rpm singles, Lucas wrote every scene with a specific musical backdrop in mind, while listening to the various record albums. American Graffiti would be the first film to feature such an extensive soundtrack of original rock and roll recordings.[14]

Universal Studios

The cost of licensing the 75 songs that Lucas wanted contributed to United Artist's rejection of the script; they saw it as "a musical montage with no characters".[4] They also passed on the science fiction idea, which Lucas temporarily shelved[4] (this would eventually become the birth of Star Wars).[3] Lucas spent the rest of 1971 and early 1972 trying to raise interest in his script for Graffiti. THX 1138 had brought him an unwelcome notoriety, and he was instead offered the chance to direct films such as Tommy (1975) and Hair (1979).[4] Lucas took the script to American International Pictures, and was told "we will accept if you make it more violent and exploitational".[16] Columbia Pictures passed on Graffiti as they felt licensing the songs would be around $500,000[17] (the final cost only came to $80,000).[18]

| "Universal was [still] being run by Lew Wasserman. He had very eccentric tastes, and he made a lot of very, very commercial movies. They did all this low-budget stuff as well. The low-budget program at Universal was based on this concept that if they liked the script, and the elements were okay with them, they in effect wrote you a check and told you to go away and come back with a finished movie. They never bothered you at all." |

| — Producer Gary Kurtz on why Universal Pictures agreed to finance American Graffiti[4] |

By the time the project was accepted at Universal Studios, four drafts of the script had already been written.[4] The studio greenlighted the film after Francis Ford Coppola signed on as producer, feeling he was commercially famous after The Godfather (1972).[19] Universal's original budget was $600,000, a small sum, even for a film in the early 1970s. Lucas persuaded the studio for a $775,000 budget, which made Coppola reluctant enough to start raising money himself, although Coppola ultimately failed. In addition, Universal optioned off Star Wars (which they later dropped in 1973).[17]

As Lucas continued to work on the script, he encountered difficulties with the storylines of Steve and Laurie. Nearly two years on from his original approach, he asked Katz and Huyck if they would work on the fifth draft, and specifically on the scenes featuring Steve and Laurie.[20] Katz and Huyck heavily argued over the ending with Lucas. Katz and Huyck wanted to tell the fate of the girls, although Lucas felt that mentioning the girls meant adding another title card, which he felt would prolong the ending. Pauline Kael accused Lucas of chauvinism because of this decision.[17] The final shooting script was 160 pages long.[20]

Production

Although the story is set in Modesto, California, George Lucas felt the city had changed too much since 1962,[21] so San Rafael was selected to stand in for Lucas' hometown. Production began on 26 June 1972 under a limited 30-day shooting schedule. Filming was interrupted by fixing camera mounts to cars, and the city of San Rafael decided to withdraw filming permission, since production was disrupting local businesses. The city of Petaluma instantly welcomed American Graffiti.[5] Supplementary shooting was also done in Sonoma, Concord (Buchanan Field airport), and San Francisco (where the scenes at Mel's Drive-In were shot). Pinole(The scene where Curt and the Pharoahs rob the pinball machines). Petaluma High School and Tamalpais High School were used for the Sock Hop scenes, as well as exteriors of the high school.[22] The Mel's Drive-In seen in Graffiti was found abandoned by the production crew and was subsequently renovated for the film.[23]

Lucas encountered various problems during filming. A key member of the production crew was arrested for growing marijuana,[24] while Paul Le Mat was sent to the hospital after an allergic reaction to walnuts. Harrison Ford, Le Mat and Bo Hopkins had climbing competitions and conducted races to the top of the local Holiday Inn sign. One actor set fire to Lucas' motel room.[25] Another night, Le Mat threw Richard Dreyfuss into a swimming pool, gashing his forehead on the day before he was due to have his close-ups filmed. Dreyfuss also complained over the wardrobe that Lucas had chosen for Dreyfuss' character.[25] Ford was arrested and kicked out of his motel room.[26] Lucas had wanted to film a scene where The Blonde (Suzanne Somers) was simply a ghost and figment of Curt's imagination, but due to the challenge of filming such a scene adequately, that story thread was dropped.[23]

Filming proceeded with virtually no input or interference from Universal Pictures. American Graffiti was a low-budget project, and the studio had only modest expectations for its commercial success. However, they did object to the film's title, having no clue what "American Graffiti" meant (some thought it was about feet). Universal submitted a long list of 65 alternative titles (with their favorite being Another Slow Night in Modesto).[5] Francis Ford Coppola and Universal also insisted on changing it to Rock Around the Block.[27] Lucas didn't like any of the choices and persuaded the studio to keep the title.[5]

Lucas had elected to shoot Graffiti with two camera operators (as he had done in THX 1138) and no formal cinematographer.[5] Lucas found CinemaScope still too expensive,[23] and insisted on an "urban documentary style", proposing the use of Techniscope. This would add features of a 16-mm camera in a widescreen frame, which Lucas felt set the boundaries between a feature length and documentary film. However, the use of Techniscope[6] and difficulty with cinematographers Jan D'Alquen and Ron Eveslage[24] presented lighting problems. Lucas called in fellow friend Haskell Wexler (who was credited as "visual consultant").[6] Wexler took the job with no money and three hours of sleep each night, similar to Lucas.[24] Wexler came up with solutions by using 1,000-2,000 watt bulbs in the scene lighting, and by asking store owners to leave the stores lighted throughout the night. Wexler placed 12-volt lights inside the cars, powered directly from the batteries, to light faces of the actors for close–ups.[6] Two camera operators nearly died when filming the climatic car race between Milner and Falfa. Dreyfuss recalled, "That car missed one camera by inches. We were all shitting in our pants!"[28] American Graffiti finished filming after 28 days.[27]

Post-production

Lucas's then wife Marcia and Verna Fields (his former teacher at USC School of Cinematic Arts) performed an initial editing cut at 165 minutes.[28] Fields left to work on What's Up, Doc?, while Lucas struggled with Graffiti's structure, as the film now went up to roughly 210 minutes. Walter Murch heavily assisted in the sound editing process.[6] Lucas' choice of background music was crucial to the mood of each scene, but he was prepared for complexities of copyright clearances and suggested a number of alternate tracks.[19]

Lucas originally proposed 80 background songs, before narrowing it down to 45.[27] The studio suggested hiring an orchestra to re-record the songs. In turn, Universal proposed a deal that offered every music publisher the same amount of money. This was acceptable to most of the companies representing Lucas' choices, but not to RCA (with the consequence that Elvis Presley's songs were not used).[19] In total, $80,000 was spent for music rights, and none for a film score.[18] By December 1972, American Graffiti was complete.[18]

Cast

- Richard Dreyfuss as Curt Henderson: Given a scholarship by the local Moose Lodge, Curt is unsure whether he wants to go to college in the East or stay at a local junior college. When a beautiful blonde girl in a 1956 Ford Thunderbird smiles at him and mouths "I love you", Curt decides to spend the rest of the night looking for her. This leads to a series of adventures such as helping "The Pharaohs" (a local greaser gang) and finding Wolfman Jack's secret radio station. In later life Curt becomes a writer living in Canada, possibly a draft dodger. Lucas selected Dreyfuss after considering more than 100 young unknown actors,[19] and gave him the choice of playing either Terry "The Toad" Fields or Curt Henderson.[21]

- Ron Howard as Steve Bolander: Steve is Curt's best friend and the boyfriend of Curt's sister Laurie. After a series of arguments between Steve and Laurie about his decision to accompany Curt to an eastern university, Laurie leaves him for Bob Falfa. By the end of the film, Steve has become less adventurous and decides to take some time off from school. We learn in More American Graffiti that Steve will ultimately graduate from business school, marry Laurie, and become an insurance agent (this latter fact is also mentioned at the end of American Graffiti).

- Paul Le Mat as John Milner: Behind the wheel of his yellow deuce coupe, John holds the title "the fastest on the strip". He picks up Carol, not realizing that she is several years younger, and is forced to "babysit" her for the remainder of the night. John races Bob Falfa, and we learn at the end that in December 1964 John will be killed by a drunk driver. This character was based on various "hot rod enthusiasts" Lucas had known in Modesto, and the name was taken from John Milius, a friend of Lucas at the USC School of Cinematic Arts.[19]

- Charles Martin Smith as Terry "The Toad" Fields: A short, bespectacled nerd who is unsuccessful with girls, Toad borrows Steve's car and meets Debbie. He spends the night trying to impress her by calling himself "Terry the Tiger" and telling bear-hunting stories. The car is eventually stolen, but is recovered with John's help. We learn that Toad will be declared missing in action in December 1965 near An Loc.

- Cindy Williams as Laurie Henderson: Laurie is madly in love with Steve, but Steve is planning to go to an eastern college and therefore suggests that they should also "see other people". In response, Laurie leaves Steve for Bob Falfa, although she eventually will marry Steve, as shown in More American Graffiti.

- Candy Clark as Debbie "Deb" Dunham: A wild and rebellious teen, Deb falls for Toad because of his "intelligence", thinking that he is smart enough to get the two of them a bottle of Old Harper whiskey.

- Mackenzie Phillips as Carol Morrison: Carol, far younger than the other main characters, is picked up by John and rides with him all night. Although they do not get along at first, they ultimately become good friends. Phillips was only 12 years old at the time, and under California law, producer Gary Kurtz had to become her legal guardian for the duration of the filming.[21]

- Harrison Ford as Bob Falfa: A street racer that drives a black 1955 Chevy Bel-Air who is slightly older than most of the teenagers he races against, Bob sports a cowboy hat and often has a girl by his side. After an argument with Steve, Laurie joins Bob, surviving the crash with John Milner at the end of the film. Falfa will become a San Francisco police officer in the future, as shown by Ford's cameo in More American Graffiti. Ford, who was concentrating on becoming a carpenter at the time, met casting director Fred Roos while remodeling Roos' home. Ford agreed to take the role on the condition that he would not have to cut his hair. A compromise was eventually reached whereby Ford wore a Stetson hat.[20]

- Bo Hopkins as Joe Young: Joe, as the leader of the gang known as "The Pharaohs", pressures Curt into helping with the gang's more criminal activities, such as stealing money from the local shop and wrecking the back axle of Officer Holstein's police car. In the sequel More American Graffiti, Joe will serve in the same unit as Toad in the Vietnam War (they even become friends), but Joe is killed by gunfire.

- Jana Bellan as Budda: Toad tries to impress Budda, a local carhop at Mel's Drive-In, only to be embarrassed by John. She is romantically attracted to Steve.

- Jim Bohan as Officer Holstein: Officer Holstein is the local police officer who hopes to "catch John in the act". The back axle of his police car is later wrecked by Curt and The Pharaohs.

- Wolfman Jack in the small, but pivotal role as Himself: A popular pirate radio disc jockey, "The Wolfman" broadcasts illegally, and the cops have yet to find him. Curt finds his station, and gets advice that will change Curt's decision about whether to stay in Modesto, or go to an Eastern college. Francis Ford Coppola encouraged Lucas to ask Wolfman Jack to portray himself. Of the character, Lucas said, "He's a legend; the mythical character I was dealing with in terms of the fantasy of radio."[20] Jack explained, "It was played as close as I could to what it really was. If anything, it was 98 percent real. George and I went through thousands of Wolfman Jack phone calls that were taped with the public. The telephone calls heard on the broadcasts in the motion picture and on the soundtrack were actual calls with real people."[20]

Kathleen Quinlan and Suzanne Somers, who were both unknown actresses at the time, have small roles in the film. Quinlan plays Peg, a popular girl at the local high school, and Somers portrays "Blonde in T-Bird", the girl Curt sees and seeks for the rest of the night. The casting call and notices went through numerous local high school drama groups and community theaters.[19] Among the actors was Mark Hamill, the future Luke Skywalker in Lucas' original Star Wars trilogy.[29] Of all the characters in the script, Curt is most representative of George Lucas, who has said that the film is somewhat autobiographical. Lucas stated, "I was Terry, fumbling with girls. Then I became a drag racer like John. And finally I became Curt."[19]

Soundtrack

The following songs appear in the soundtrack of the movie:

A 2-LP soundtrack album, 41 Original Hits from the Soundtrack of American Graffiti, was released by MCA Records in 1973. It features most of the songs heard in the film, interspersed with spoken dialogue by Wolfman Jack. Three songs from the film (the Crows' "Gee", Flash Cadillac's "Louie, Louie", and Harrison Ford's in-character a capella rendition of "Some Enchanted Evening") were omitted from the album. MCA reissued the soundtrack on CD in 1993.

A second compilation, titled More American Graffiti (and not to be confused with the film sequel of that name) was issued by MCA in 1975, with Lucas's approval. It features more rock and doo-wop hits from the late '50s and early '60s (only one of which, the Crows' "Gee", was featured in the film), along with additional Wolfman Jack dialogue.

Release

A premiere screening was held for Universal Studios executives and the public on January 28, Template:Fy.[30] Producer Gary Kurtz tape-recorded the audience to see which scenes drew most laughter.[28] While the public audience greeted American Graffiti with positive response and thunderous applause, Universal was less enthusiastic. This prompted an argument between Francis Ford Coppola and executives in which Coppola offered to buy the film from them immediately, an offer Universal refused.[30] Coppola stated, "You should go down on your knees and thank George. This kid has killed himself to make this movie for you. He brought it on time and on schedule."[26]

In the words of George Lucas' friend Matthew Robbins, "it only reaffirmed so many of George's feelings about what Hollywood was made of".[31] Universal was constantly telling Lucas "a lot of editing work has to be done for this to be a completed film". Lucas mostly ignored their instructions, until they threatened to have William Hornbeck completely re-edit the film.[32] Only four-and-a-half minutes of edits were taken out, including Toad's encounter with a car salesman, an argument between Steven and former teacher Mr. Kroot at the sock hop, and Bob's effort to sing Some Enchanted Evening to Laurie. Universal then told Lucas they were going to release American Graffiti as a TV movie.[31] 20th Century Fox and Paramount Pictures offered to buy Graffiti from Universal, seeing the prospect of a successful film.[32] Eventually, good word of mouth around various employees at Universal prompted the studio to set a theatrical release date and spend $500,000 on a marketing campaign.[31][1]

Reaction

American Graffiti opened on August 1, Template:Fy, eventually earning over $115 million in North America. The film was a box office success, recouping 92 times its budget of $1,250,000[8], and is is often cited for helping give birth to the summer blockbuster.[33] Graffiti was the highest cost-to-profit success in film history,[1] until surpassed by The Blair Witch Project in 1999.[34] Adjusted for inflation the film became the 41st highest grossing movie in North America.[35] George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola had a controversy over control of box office profits, affecting their friendship.[1] Film rentals went up to a staggering $55,886,000. However, Graffiti was less successful in foreign countries, earning only five million dollars overseas, although the film developed a cult following in France. Lucas stated, "Francis [Coppola] was kicking himself forever for the fact that if he had financed the film himself, he would have been a rich man." No one expected Graffiti to be a financial success, least of all Lucas.[1]

Based on 31 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, American Graffiti received an average 97% overall approval rating.[7] Jay Cocks felt the film captured "the charm and tribal energy of the teen-age 1950s, and the listlessness and the resignation that underscored it all like an incessant bass line in one of the rock-'n'-roll songs of the period".[36] Roger Ebert felt the film reminded him of his teenage days, citing that he connected with the stories and characters. He quoted, "I can only wonder at how unprepared we were for the loss of innocence that took place in America with the series of hammer blows beginning with the assassination of President Kennedy."[37] Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader called it "a brilliant work of popular art" and stated he was impressed at how the film established a new narrative style.[38] A.D. Murphy of Variety was impressed with the basic premises that included the cast, dialogue, story, design and direction.[39]

Awards and honors

At the 46th Academy Awards, American Graffiti was nominated for five categories, losing four of them (Best Picture, Director, Original Screenplay and Editing) to The Sting. Candy Clark lost the Best Actress in a Supporting Role nomination to Tatum O'Neal (only 10-years old at the time) of Paper Moon.[9] The film was able to win Best Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy) at the Golden Globe Awards while Paul Le Mat won Most Promising Newcomer of the year. George Lucas received the nomination for Best Director and Richard Dreyfuss was nominated for Best Actor in a Comedy or Musical.[40]

Cindy Williams was nominated by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts with a Best Actress in a Supporting Role nomination.[41] Lucas received a nomination from the Directors Guild of America,[42] while the Writers Guild of America, East honored Lucas, Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck for a Best Comedy Written Directly for the Screen Award.[43] Entertainment Weekly listed American Graffiti as the seventh best in its list of "The 50 Best High School Movies".[44] In 1995, this film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[10] In June 2007, the American Film Institute ranked American Graffiti as #62 for its 100 Years... 100 Movies list.[45] American Graffiti was #43 in AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs.[46]

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #77

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs #43

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #62

Home video

When American Graffiti was first released on home video, George Lucas was able to add three deleted scenes that didn't appear in the theatrical cut.[47] The film had been released various times in VHS before the debut of DVD.[48] American Graffiti was first released on DVD in September Template:Fy, only including the documentary The Making of American Graffiti,[49] and again with the same specifications, but as a double feature with More American Graffiti (Template:Fy) in January 2004.[50]

Legacy

The film's box office success made George Lucas an instant millionaire. He gave a large amount of the film's profits to Haskell Wexler for his visual consulting help during filming, and to Wolfman Jack. Lucas's net worth was now $4 million, and he set aside a $300,000 fund for his long cherished science fiction project, which he would eventually title The Star Wars.[22] With his profits from the film, Lucas was able to establish more elaborate development for his company Lucasfilm and created what would become the successful companies Industrial Light & Magic and Skywalker Sound.[22] A sequel, titled More American Graffiti (1979), told the further stories of John Milner becoming a drag racer, Steve's and Laurie's marriage, Deb becoming a country western singer, and Toad in the Vietnam War.

Lucas, Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck later collaborated on Radioland Murders (1994), released by Universal Pictures, for which Lucas also acted as executive producer. The film features characters intended to be Curt and Laurie Henderson's parents, Roger and Penny Henderson. Additionally, several actors from American Graffiti appeared as unrelated characters.[22] David Fincher credited American Graffiti as a visual influence for the film Fight Club (1999).[51] Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002), also directed by Lucas, features references to American Graffiti. The yellow airspeeder that Anakin Skywalker and Obi-Wan Kenobi use to pursue the bounty hunter Zam Wesell is based on John Milner's yellow deuce coupe[52] while Dex's Diner is reminiscent of Mel's Drive-In.[53] Elements of the film were later parodied in The Simpsons episodes Take My Wife, Sleaze.[54]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Pollock, p.123-130.

- ^ a b c d Hearn, p.52

- ^ a b Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy. Lucasfilm. 2005.

{{cite AV media}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Hearn, p.54

- ^ a b c d e Hearn, p.60–61

- ^ a b c d e Hearn, p.62–66

- ^ a b "American Graffiti". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ a b "American Graffiti (1973)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b "American Graffiti". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ a b "National Film Registry: 1989-2007". National Film Registry. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ a b Baxter, p.106–11

- ^ a b Baxter, p.112–17

- ^ a b c Pollock, p.101–05

- ^ a b c d Hearn, p.53

- ^ "A Life Making Movies". Academy of Achievement. 1999-06-19. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Baxter, p.118–20

- ^ a b c Pollock, p.106–07

- ^ a b c Hearn, p.67

- ^ a b c d e f g Hearn, p.55-57.

- ^ a b c d e Hearn, p.58

- ^ a b c Baxter, p.125-126.

- ^ a b c d Hearn, p.72–82

- ^ a b c Baxter, p.127–28

- ^ a b c Pollock, p.111–13

- ^ a b Pollock, p.114–15

- ^ a b Baxter, p.129–36

- ^ a b c Pollock, p.108–09

- ^ a b c Pollock, p.116–19

- ^ Baxter, p.121–24

- ^ a b Hearn, p.69–70

- ^ a b c Hearn, p.71

- ^ a b Pollock, p.120–22

- ^ "The Evolution of the Summer Blockbuster". Entertainment Weekly. 1991-05-24. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". Box Office Mojo.com. 2006-01-01. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "All Time Box Office Adjusted for Inflation in North America". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ Cocks, Jay (1973-08-20). "Fabulous '50s". Time. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1973-08-11). "American Graffiti". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Kehr, Dave. "American Graffiti". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Murphy, A.D. "American Graffiti". Variety. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ "The 31st Annual Golden Globe Awards (1974)". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ "Supporting Actress 1974". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ "DGA Awards: 1974". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "WGA Awards: 1974". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "The 50 Best High School Movies". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "Citizen Kane Stands the Test of Time" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ^ "AFI's 100 YEARS...100 LAUGHS". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ The Making of American Graffiti. Universal Pictures / Lucasfilm. 1998.

{{cite AV media}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Merchandise for American Graffiti". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "American Graffiti (Collector's Edition)". Amazon. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "American Graffiti / More American Graffiti (Drive-In Double Feature)". Amazon. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "Movie Preview: Oct. 15". Entertainment Weekly. 1999-08-13. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "Anakin Skywalker's Airspeeder". StarWars.com. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ "Dex's Diner". StarWars.com. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ "Take My Wife, Sleaze". Neil Affleck, John Swartzwelder. The Simpsons. 1999-11-28. No. 234, season 11 and Summer of 4 Ft. 2.

Bibliography

- Baxter, John (1999). Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas. Avon Books. ISBN 0380978334.

- Hearn, Marcus (2005). The Cinema of George Lucas. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0810949687.

- Pollock, Dale (1999). Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas: Updated Edition. DaCapo Press. ISBN 0306809044.

External links

- Official Website at Lucasfilm

- American Graffiti at IMDb

- American Graffiti at the TCM Movie Database

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› American Graffiti at AllMovie

- American Graffiti at Filmsite.org

- American Graffiti at Rotten Tomatoes

- American Graffiti at Box Office Mojo

- Kip Pullman's American Graffiti Web Page

- The City of Petaluma's Salute to American Graffiti

- da Hui Presents All Graffiti All The Time

- American comedy films

- 1970s comedy films

- Baby boomers in fiction

- 1973 films

- Universal Pictures films

- Lucasfilm films

- Films directed by George Lucas

- Auto racing films

- Road movies

- Comedy-drama films

- Coming-of-age films

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films set in California

- Teen comedy films

- Best Musical or Comedy Picture Golden Globe winners

- United States National Film Registry films

- Kustom Kulture