Russian partisan movement (2022–present)

| Russian partisan movement | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the anti-war protests in Russia (2022–present) | |||||||

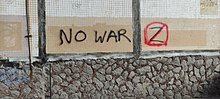

Anti-war graffiti in Saint Petersburg | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| Deaths: 40+[29][30][31] | ||||||

| |||||||

Pro-democratic and pro-Ukrainian partisan movements have emerged in Russia following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War. These resistance movements act against the authoritarian government of Vladimir Putin in Russia, as well as against civilian supporters of these authorities and the armed forces, with the aim of stopping the war.[32]

Attacks on property of authorities and supporters of the war

[edit]By 2022-03-07, cases of arsons of police departments were recorded in Smolensk and Krasnoyarsk.[33]

As of 5 July 2022[update], at least 23 attacks on military enlistment offices were recorded, 20 of which were arson.[34] The arson attacks were not a single coordinated campaign: behind them were a variety of people: from far-left to far-right groups. Sometimes they were lone actors who did not associate themselves with any movements.[35][36] Civilian vehicles bearing the letter Z insignia (supporting the war efforts) were also set ablaze.[32]

On 2022-08-27, multiple Russian-language outlets reported that a woman named Evgenia Belova doused a parked BMW X6 with accelerant and set it ablaze in Moscow. The vehicle belonged to Yevgeny Sekretarev (Russian: Евгения Секретарева) who reportedly works for the Eighth Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation; the Directorate oversees the State Secret Protection Service handling wartime censorship. A woman detained for the arson also reportedly proclaimed her opposition to the war.[37][38][39][40][41] The woman is described as 65 years old, a patient of a local "psychoneurological clinic," and lives in the same building as Sekretarev.[42] Coverage of the incident by Radio Svoboda, mentioned a relative of the woman making the unverified claim that she was "kidnapped prior to the arson by Ukrainian special forces," held for a "ransom of 500,000 Russian rubles", and "hypnotized." The woman's relatives further insisted she "was never against the Russian authorities", and "would never have committed arson against the Russian government".[43]

Rail war

[edit]In Russia, the movements Combat Organization of Anarcho-Communists (BOAK) and Stop the Wagons announced their sabotage activities on the railway infrastructure. According to The Insider, 63 freight trains derailed in Russia between March and June 2022, about one and a half times as much as during the same period the previous year. At the same time, the geography of wagon wrecks shifted to the west, and some trains got into accidents near military units.[35] According to Russian Railways and inspection bodies, half of the accidents are related to the poor condition of the railway tracks.[44]

Attributed to BOAK

[edit]Representatives of BOAK took responsibility not only for dismantling rails and railway sabotage in Sergiyev Posad near Moscow and near Kirzhach, Vladimir Oblast, but also for setting fire to cell towers (for example, in the village of Belomestnoye in the Belgorod Oblast) and even for setting fire to cars of people supporting actions of the Russian leadership. According to the anarchists themselves, their activities were largely inspired by the actions of the Belarusian partisans, who effectively resisted the Russian invasion through the territory of Belarus at the very beginning of the war.[35]

Attributed to Stop the Wagons

[edit]The "Stop the Wagons" movement in Russia claimed responsibility for the derailment of wagons in the Amur Oblast, due to which traffic on the Trans-Siberian Railway was stopped on 29 June,[45][46][47][48] for the derailment of a train in Tver on 5 July,[49] several wagons with coal in Krasnoyarsk on 13 July,[50] as well as freight trains in the Krasnoyarsk Krai at the Lesosibirsk station on 19 July,[51] in Makhachkala overnight between 23 and 24 July (the investigating authorities of Dagestan also considered sabotage as a probable cause of this incident)[52][53] and on the Oktyabrskaya railway near Babaevo station on 12 August.[54] According to the map published by the movement, its activists operate on more than 30% of the territory of Russia.[55][56]

Assassinations

[edit]Assassination of Darya Dugina

[edit]On 20 August 2022, ultranationalist journalist, political scientist and activist Darya Dugina was killed by a car bombing in Bolshiye Vyazyomy, Odintsovsky District, Moscow Oblast.[57] it is widely presumed the bomb was also meant to kill her father, Aleksandr Dugin. Both are identified with National Bolshevism, gave statements justifying war against Ukraine, and denied war crimes such as Bucha massacre.[58][59] The United States sanctioned both figures for their support of the regime and the war; Dugina was also sanctioned for her work with Yevgeny Prigozhin in the Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections.[60]

Former State Duma deputy Ilya Ponomarev, who is based in Kyiv, said that a partisan organization called the "National Republican Army" operating inside Russia and engaged in "overthrowing the Putin regime" was behind the assassination of Dugina; Ponomarev also called the event a "momentous event" and said that the partisans inside Russia were "ready for further similar attacks".[61] Ponomarev told several outlets that he had been "in touch" with representatives of the organization since April 2022, while also claiming that the group had been involved in "unspecified partisan activities".[62] However, the veracity of Ponomarev's claims not withstanding and his endorsement of armed action against the regime resulted in his blacklisting by the Russian Action Committee, an anti-Putin exile group. According to the committee's statement, this was because he "called for terrorist attacks on Russian territory," The committee's statement also implied that Dugina was a "civilian" who "did not take part in the armed confrontation," and condemned denunciations of Aleksandr Dugin following the attack as "a demonstrative rejection of normal human empathy for the families of the victims."[63][64]

Assassination of Vladlen Tatarsky

[edit]On 2 April 2023, a bombing occurred in the Street Food Bar No.1 café on Universitetskaya Embankment in Saint Petersburg, Russia, during an event hosted by Russian military blogger Vladlen Tatarsky (real name Maxim Fomin), who died as a result of the explosion.[65][66][67] 42 people were also injured, 24 of whom were hospitalized, including six in critical condition.[68][69][70] The bomb was allegedly hidden inside a statuette and handed to him as a gift by an "unidentified woman".[71]

Russia accused Ukraine of being behind the attack and labelled it a "terrorist act", while Ukraine blamed the attack on "domestic terrorism".[72] The National Republican Army also claimed responsibility for the attack.[73] Darya Trepova, a Russian citizen, was later convicted to 27 years in prison for the attack in 2024.[73]

Other assassinations

[edit]On 6 May 2023, in Pionerskoye village, Bor District, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, an anti-tank mine exploded under an Audi Q7 car, in which the ultranationalist writer and politician Zakhar Prilepin was driving. Prilepin received severe leg injuries, and his bodyguard died on the spot. Responsibility for the attack was claimed by Atesh, a militant group of Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars.[74][75]

On 11 July 2023, Navy Captain Stanislav Rzhitsky, deputy head of military mobilization efforts in Krasnodar, was shot and killed while jogging. As commander of the submarine Krasnodar based in the Black Sea, he was accused of launching missiles that struck Vinnytsia in July 2022 and killed 23 civilians, although his father claimed he had left active service prior to the invasion in 2021.[76]

Ground incursions

[edit]Bryansk Oblast incursions

[edit]Belgorod and Kursk Oblasts incursions

[edit]May-June 2023

[edit]

On 22 May, another cross-border raid took place, this time in the Belgorod Oblast; in the Kozinka, Gora-Podol and Grayvoron districts. The Freedom of Russia Legion (FRL) and Russian Volunteer Corps (RVC), as well as allied Polish, Belarusian and Chechen militant groups, claimed responsibility for the attacks. A Ukrainian spokesperson, Andrii Yusov, made the same claim, stating that the attacks were to "liberate" the regions and to provide a buffer zone to protect Ukrainian civilians. Russian authorities attributed the attacks to "a Ukrainian sabotage-reconnaissance group", and imposed a "counter-terrorist operation regime" in the region to combat the incursion.[80] The anti-government forces, however, left Russian territory on May 24, with the exception of a few soldiers who would stage a short incursion into Glotovo on May 25.[81][82]

On 1 June, the FRL and RVC, alongside their allied groups, launched another raid into Belgorod Oblast, this time near the small towns of Shebekino and Novaya Tavolzhanka, with Belgorod City itself being the target of UAV and missile attacks.[83] Most troops left however on June 17, after Russian forces retook control of Novaya Tavolzhanka two days prior, with sporadic incursions and shellings soon ensuing through the rest of June and July.[84]

On 19 June, Russian sources claimed that 7 civilians where wounded due to anti-government shelling in Belgorod.[85] And on 22 June, the Russian ministry of Defense claimed to have used thermobaric weapons against remaining partisans in the Oblast.[86] During the Wagner Group rebellion on 24 June, it was noted by the Atlantic Council that some anti-government partisans were still operating in Belgorod, organizing ambushes on Russian troops and sabotage of important military infrastructure.[87]

July-December 2023

[edit]In mid-July, the Ukrainian Main Directorate of Intelligence published a video showing Chechen volunteers of the Separate Special Purpose Battalion ambushing a Russian military truck at Sereda, Belgorod, killing two Russian soldiers.[88]

On 28 September, the Freedom of Russia Legion claimed that it had begun another raid into Belgorod Oblast. The Russian Astra Telegram channel also stated that Russian troops were battling pro-Ukrainian forces at the border.[89]

On 17 December 2023, the FRL and RVC partisans launched yet another raid into Belgorod. According to a Russian official and other Russian as well as Ukrainian sources, the insurgents targeted the Morozovsk airbase with "mass drone strikes", while clashing with security forces at the village of Terebreno.[90][91] The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence subsequently claimed that a Russian "platoon stronghold" at Terebreno had been destroyed by the rebels.[92] The Freedom of Russia Legion claimed responsibility for the raid, and stated that it had withdrawn from Russian territory after mining the eliminated "stronghold" at Terebreno.[91]

March-April 2024

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2024) |

On 12 March 2024, the FRL and RVC, alongside allied Chechen and Romanian militant battalions launched raids into the Kursk and Belgorod Oblasts, claiming control of Tyotkino and Lozovaya Rudka.[93][94] The raids continued until April 7, with anti-government forces claiming control of several villages in the meantime such as Gorkovsky and Kozinka, most forces however later left the region back into Ukraine.[95]

Involved groups

[edit]National Republican Army (NRA)

[edit]Purported manifesto

[edit]Ponomarev read the NRA's purported manifesto on a YouTube channel he owns, February Morning (Russian: Утро Февраля).[96] The text of the manifesto was also shared over February Morning's affiliated Telegram channel, Rospartizan (Russian: Роспартизан).[97] As of 26 August 2022[update], YouTube's metrics indicate video containing the claim of responsibility and sharing the manifesto is February Morning's most-seen video with 176,646 views.[96]

In a May 2022 conference of exiles in Vilnius sponsored by the Free Russia Forum, Ponomarev appealed to attendees to support direct action within Russia. A Spektr (Russian: Спектр) reporter noted an indifferent response from the attendees.[98]

Doubts of NRA's existence

[edit]Doubts of the NRA's responsibility and its very existence have been raised by a wide variety of commentators.[99][100] A 22 August 2022 report from Reuters says that "[Ponomarev's] assertion and the group's existence could not be independently verified."[101] As for the assassination of Dugina, the sole suspect named by Russian investigators is a Ukrainian woman whom, Russia claims, is part of its military. The Russian government has also stated that the woman fled to Estonia following the assassination.[102] The governments of Ukraine and Estonia each denied any role in the assassination of Darya Dugina.[103][104][105]

Reaction of the authorities

[edit]The Russian authorities were forced to tighten security measures on the railways following the derailing of trains by resistance movements.

On 8 May 2022, the Telegram channel of the Stop the Wagons movement was blocked. According to their own statements, they were blocked "after the publication of a map of railway resistance, which covered over 30% of the territory of Russia."[106][107] On 19 July, the website of Stop the Wagons was also blocked by Roskomnadzor in Russia at the request of the Prosecutor General's Office.[108][109]

In August 2022, a court in Moscow fined the Telegram messenger 7 million Russian rubles (quoted by TASS as equivalent to US$113,900) for refusing to remove channels providing instructions for railway sabotage and containing "propaganda pushing the ideology of anarchism."[110][111][112]

See also

[edit]- Popular Resistance of Ukraine

- Suspicious deaths of Russian businesspeople (2022–2024)

- Ukrainian resistance during the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Belarusian partisan movement (2020–present)

- Primorsky Partisans

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Zemlyanskaya, Alisa (5 July 2022). "Этот поезд в огне: как российские партизаны поджигают военкоматы и пускают поезда под откос". The Insider (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ "Этот поезд в огне: как российские партизаны поджигают военкоматы и пускают поезда под откос" [This train is on fire: how Russian partisans set fire to military enlistment offices and derail trains]. The Insider (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ ""Рельсовые диверсанты" сообщили о сходе поезда в Твери". Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "Жечь военкоматы и готовиться к революции. Представители антипутинского подполья о жизни после мобилизации" [Burn the military commissariats and prepare for the revolution. Representatives of the anti-Putin underground about life after mobilization]. Vot Tak (Belsat) (in Russian). Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Smart, Jason Jay (23 August 2022). "Exclusive interview: Russia's NRA Begins Activism". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Российская оппозиция начинает вооруженное сопротивление Путину: подписано декларацию". Главком | Glavcom (in Russian). 31 August 2022. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Краткий курс NS/WP. Что мы знаем о задержанных за покушение на Соловьева — и о том, кто жег военкоматы" [An Introduction to NS/WP: What do we know about those detained for the assassination attempt on Solovyov - and about who burned the military registration and enlistment offices?]. Медиазона (in Russian). Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Выяснилось, что Хачикян, стрелявший в сотрудника ОМОН, разделяет взгляды экстремистской группы "Артподготовка"*". Петербургский дневник (in Russian). 25 February 2023.

- ^ "Источник сообщил о задержании пяти человек, готовивших провокацию на 9 мая". РИА Новости (in Russian). 5 May 2023.

- ^ "В Петербурге и Оренбургской области подожгли военкоматы". Медиазона (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Abbey Fenbert (6 December 2024). "Ukrainian partisans sabotage railway line linking Moscow to Kursk Oblast, group claims". The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "Охота на тех, кто проводит мобилизацию: в Дагестане создали партизанское движение". 24 Канал (in Russian). 25 September 2022. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Началова, Марина (25 September 2022). "Протестующие в Дагестане объявили о старте партизанского движения и выдвинули ультиматум: "Трассы запылают!"". Новости в 'Час Пик' (in Russian). Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ "Circassian protest plays key role in killing Putin's mobilization program – the Ukrainian Weekly". 21 October 2022.

- ^ "Circassian Protest Plays Key Role in Killing Putin's Mobilization Program". Jamestown.

- ^ "Ingush activists announced the formation of the Ingush Liberation Army, threatening the Kremlin's regional presence and strategy". SpeciaEurasia.

- ^ "Воюющие за Украину чеченские бойцы не встретили сопротивления в Белгородской области – ее охраняют кадыровцы" (in Russian). 18 July 2023.

- ^ "Ичкерийские отряды на Украине" (in Russian). 18 August 2023.

- ^ https://t.me/IADAT/14657 Принесите палатки и стройте барикады. Помогайте тем, кто уже несколько часов на митинге. Все в центр, и до конца никуда не уходим. Да хранит вас Аллах.

- ^ ""Это не наша война. Украинцы нам ничего плохого не делали". Башкирские националисты объявили о создании вооруженного сопротивления". The Insider (in Russian). Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "Liberation forces raised flags in another village in Belgorod region". Militarnyi. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ "В Карелии 18-летнего студента арестовали по делу о госизмене". Радио Свобода (in Russian). 9 March 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ ""Насилие для нас омерзительно". Студента в Карелии обвиняют в подготовке теракта". Sever Realii (in Russian). 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine-backed anti-Kremlin fighters say they are still operating inside Russia". Reuters. 21 March 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "In Memory of Dmitry Petrov". CrimethInc. 3 May 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "В Москве арестовали еще одного подозреваемого в подготовке покушения на Соловьева". tass.ru. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ "Russia Accuses Ex-Soldier of Helping Ukraine Organize Arson Attacks". 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Russia Says Arrested Belarusian for Siberia Railway Sabotage". 7 December 2023.

- ^ ""Русский добровольческий корпус" заявил, что вошёл в село на Брянщине". Радио Свобода (in Russian). 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ ""Они видели, что в машину садятся два человека. И думали, что второй — Дугин" Интервью Ильи Пономарева. Он комментирует убийство Дугиной от лица мистической "Национальной республиканской армии," которая, по его словам, устроила этот взрыв" ["They saw that two people were getting into the car. And they thought that the second one was Dugin" Interview with Ilya Ponomarev. He comments on the murder of Dugina on behalf of the mysterious "National Republican Army," which, according to him, carried out this explosion.]. Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Artyushenko, Oleg (17 June 2023). "'Everyone For Themselves': Attacks In Border Towns And Cities Bring The War To Russia's Doorstep". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Коктейли Молотова и рельсовая война — стратегия новой российской оппозиции. Роман Попков поговорил с "партизанами" об их методах борьбы" [Molotov cocktails and rail war: the strategy of the new Russian opposition. Roman Popkov speaks with the "partisans" about their methods of struggle]. БелСат (in Russian). 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Полицейских предупредили о возможных поджогах: уже пострадал военкомат" [Police were warned about possible arson: military registration and enlistment offices already hit]. www.mk.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Baza: в России задержаны двое подозреваемых в поджогах военкоматов" [Baza: two suspects in arson of military registration and enlistment offices detained in Russia]. Радио Свобода (in Russian). 5 June 2022. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b c ""Изображал флейту, пел — охранники его били". Кто такой Илья Фарбер — бывший сельский учитель, арестованный за поджог военкомата" [“He played a flute, sang - the guards beat him.” Who is Ilya Farber - the former village teacher arrested for setting fire to a military registration and enlistment office?]. Медиазона (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ ""Сплошное белое пятно": кто поджигает военкоматы в России" ["A solid white spot": who is setting military registration and enlistment offices ablaze in Russia?]. NEWS.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "976". Telegram (in Russian). Роспартизан. 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "12954". Telegram (in Russian). Baza. 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "12956". Telegram (in Russian). Baza. 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "11772". Telegram (in Russian). 112. 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "СМИ: в Москве подожгли автомобиль замначальника Генштаба ВС России" [Media: in Moscow, car of the Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces set ablaze]. Главные события в России и мире | RTVI (in Russian). 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Car of Russian General Staff official set on fire in Moscow, woman detained – Russian media". Ukrainska Pravda. 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Москвичку, которая подожгла BMW сотрудника Генштаба, могли обмануть" [Muscovite who set fire to the BMW of a member of the General Staff may have been deceived]. Радио Свобода (in Russian). 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "На РЖД сходят с рельсов вагоны – почему?" [Wagons derailed at Russian Railways - why?]. www.rzd-partner.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Антивоенные активисты взяли ответственность за сход с рельсов вагонов в Приамурье" [Anti-War Activists Take Responsibility for the Derailment of Wagons in the Amur Region]. Новые Времена (in Russian). 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "В Приамурье 19 вагонов сошли с ж/д-путей, остановлен Транссиб. Ответственность за диверсию взяли на себя антивоенные активисты" [In the Amur region: 19 wagons derailed, the Trans-Siberian stopped. Anti-war activists claim responsibility for sabotage]. Общая Газета.eu. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "ACLED Regional Overview: Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia (25 June-1 July 2022)". ReliefWeb. 7 July 2022.

- ^ Szabelak, Adam (1 July 2022). "Partyzanci kolejowi w Rosji przyznali się do wykolejenia wagonów na Dalekim Wschodzie" [Railway Partisans in Russia Admit to Derailing Carriages in the Far East]. Kresy (in Polish).

- ^ ""Рельсовые диверсанты" сообщили о сходе поезда в Твери" ["Rail Saboteurs" report derailment of a train in Tver]. Новые Времена (in Russian). Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "В Красноярске сошли с рельсов 8 вагонов" [8 Wagons Derailed in Krasnoyarsk]. Новые Времена. Archived from the original on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "В Красноярском крае сошел с рельсов поезд" [Train Derailed in Krasnoyarsk Territory]. Новые Времена. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "В Махачкале "из-за аномальной жары" сошел с рельсов поезд" [Train Derailed in Makhachkala "Due to Abnormal Heat"]. newtimes.ru. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Товарные вагоны на перегоне между Калмыкией и Дагестаном сошли с рельсов из-за диверсии – источник" [Freight cars on the haul between Kalmykia and Dagestan derailed due to sabotage - source]. RFE/RL (in Russian). 25 July 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Активисты жд-сопротивления сообщили о сходе вагонов" [Railway Resistance Activists Report Derailment of Wagons]. Новые Времена (in Russian). Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Кочкина, Катерина (13 March 2022). "Поджоги военкоматов и железнодорожное сопротивление. Как действует антивоенное подполье в России" [Arson of military enlistment offices and railway resistance. How the anti-war underground operates in Russia]. Настоящее Время. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ Ostrov, Georgiy (12 May 2022). "Russische Anti-Kriegs-Bewegung berichtet über Sabotage gegen Bahnstrecken" [Russian anti-war movement reports sabotage against railway lines]. Tichys Einblick (in German). Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Darya Dugina: Daughter of Putin Ally killed in Moscow blast

- ^ "Daria Dugina's assassination could spell trouble for Putin's allies in Russia". NPR.org. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Tawfeeq, Mohammed; Pennington, Josh; Hallam, Jonny; John, Tara; Picheta, Rob (21 August 2022). "Car bomb kills daughter of 'spiritual guide' to Putin's Ukraine invasion - Russian media". CNN. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Treasury Sanctions Russians Bankrolling Putin and Russia-Backed Influence Actors". United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Ex-Russian MP claims Russian partisans responsible for Moscow car bomb". the Guardian. 21 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "Знищення Дугіної. Насильницький супротив буде зростати, іншого шляху немає – Ілля Пономарьов" [Liquidation of Dugina: "Violent resistance will grow, there is no other way" - Ilya Ponomarev]. YouTube. Радіо НВ. 22 August 2022.

- ^ "Заявление Российского комитета действия от 22 августа 2022 года" [Statement of the Russian Action Committee of August 22, 2022]. Комитет действия (in Russian). Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Statement of the Russian Action Committee 22.08.2022". Russian Action Committee (in Russian and English). Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Alert: Russian media say a famous military blogger has been killed in an apparent bombing attack at a café in St. Petersburg". The Middletown Press. 2 April 2023. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Trevelyan, Mark; Light, Felix; Trevelyan, Mark (2 April 2023). "Russian military blogger killed in St Petersburg bomb blast - agencies". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Stepanenko, Kateryna and Kagan, Frederick W. (2 April 2023). Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, April 2, 2023 Archived 3 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ Новости, Р. И. А. (4 April 2023). "После взрыва в Петербурге за медпомощью обратились 42 человека" [After the explosion in St. Petersburg, 42 people asked for medical help]. РИА Новости (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ "Минздрав: 42 человека обратились за медпомощью после взрыва в Петербурге - Газета.Ru | Новости" [Ministry of Health: 42 people asked for medical help after the explosion in St. Petersburg - Gazeta.Ru | News]. Газета.Ru (in Russian). 4 April 2023. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ Денисовна, Косолапова Арина (4 April 2023). "Число пострадавших от взрыва в Санкт-Петербурге увеличилось до 42" [The number of victims of the explosion in St. Petersburg increased to 42]. Известия (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ "Russian blogger killed in St. Petersburg explosion". euronews. 2 April 2023. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Eckel, Mike (29 April 2022). "Blasts, Bombs, and Drones: Amid Carnage in Ukraine, a Shadow War on the Russian Side of the Border". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Russian woman sentenced to 27 years for handing bomb to war blogger". Reuters. 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Zakhar Prilepin: Russian pro-war blogger injured in car bomb". BBC News. 6 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Abbakumova, Natalia; Ilyushina, Mary; Stern, David L.; Francis, Ellen (10 May 2023). "Pro-Kremlin writer wounded in car explosion in Russia". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Russian ex-navy commander shot dead while jogging in Krasnodar". BBC. 11 July 2023.

- ^ Blann, Susie (2 March 2023). "Kremlin accuses Ukrainian saboteurs of attack inside Russia". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Vasilyeva, Nataliya (2 March 2023). "Fringe Russian fighters claim responsibility for raid on border villages". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Dixon, Robyn; Ebel, Francesca; Ilyushina, Mary (2 March 2023). "Kremlin accuses Ukraine of violent attack in western Russia". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

The Anti-Defamation League describes [Denis Nikitin] as a "neo-Nazi" who lived in Germany for many years.

- ^ "Ukraine's military intelligence confirms operation by Russian anti-government groups in Belgorod region". The Kyiv Independent. 22 May 2023. Wikidata Q118585330. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023.

- ^ Shukla, Seb (24 May 2023). "Belgorod governor lifts "counter-terrorist operation," claiming region was targeted by Ukrainian armed forces". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Russia partisans stage new incursion into Russia – and show video proof". The New Voice of Ukraine. 25 May 2023.

- ^ "Russia thwarts more Belgorod attacks, blames Ukraine". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Belgorod region governor Gladkov: enemy no longer present in region. He previously said that authorities could not enter territory of Novaya Tavolzhanka due to non-stop shelling". Novaya Gazeta Europe. 6 June 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ "Seven injured in Ukrainian shelling of Russia's Belgorod - governor". The Jerusalem Post. Reuters. 19 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia is using Thermobaric missiles on insurgents inside its own borders". Team Mighty. Yahoo! News. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Herbst, John E. (24 June 2023). "Putin is losing control of Russia". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Pro-Ukrainian Chechens Ambush Russian Supply Truck in Belgorod". Atlas News. 17 July 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ OLEKSANDR SHUMILIN (28 September 2023). "Freedom of Russia Legion claims they fight in Russia's Belgorod Oblast". pravda.com.ua. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Ukrainian Forces Reportedly Press Fight Inside Russia, Target Air Base, Battle Near Border Village". RFERL. 17 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Ukraine-based Russian paramilitaries claim cross-border attack". Reuters. 18 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "Russian stronghold destroyed in combat clashes in Belgorod Oblast, Russia". Yahoo News. 17 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine-based Russian armed groups claim raids into Russia". BBC News. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "ASTRA". Telegram. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "Anti-Kremlin militia says 'hot phase' of recent incursions into Russia is over". The Kyiv Independent. 8 April 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ a b "В РОССИИ СОЗДАНА НАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ РЕСПУБЛИКАНСКАЯ АРМИЯ, ОСУЩЕСТВИВШАЯ ПОКУШЕНИЕ НА ДУГИНА" [Statement of The National Republican Army (NRA) OF 2022-08-21], Утро Февраля (in Russian), YouTube, 21 August 2022, archived from the original on 31 August 2022, retrieved 21 August 2022

- ^ "ЗАЯВЛЕНИЕ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЙ РЕСПУБЛИКАНСКОЙ АРМИИ (НРА) ОТ 21.08.2022" [Statement of The National Republican Army (NRA) OF 2022-08-21]. Роспартизан (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Kadik, Lev (22 May 2022). "Заикнулись о вооруженной борьбе. "Спектр" понаблюдал за антивоенной конференцией Форума свободной России в Вильнюсе" [Hinting at armed struggle: Spektr watched the anti-war conference of the Free Russia Forum in Vilnius]. Спектр-Пресс (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche, Nobody had previously ever heard of the National Republican Army: Prof. Sergey Radchenko | DW | 22 August 2022, retrieved 23 August 2022

- ^ Young, Cathy (25 August 2022). "The Dugina Killing Aftermath". The Bulwark. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Russia accuses Ukraine of killing nationalist's daughter, Putin gives her award". Reuters. 22 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Russia blames Ukraine for nationalist's car bombing death". Washington Post. 22 August 2022.

- ^ Troianovski, Anton; Nechepurenko, Ivan; Gettleman, Jeffrey (21 August 2022). "Russia Opens Murder Investigation After Blast Kills Daughter of Putin Ally". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "A car bomb killed the daughter of a Putin ideologist Saturday. Ukraine denies involvement: 'We are not a criminal state like Russian Federation'". Fortune. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ ERR (23 August 2022). "Minister: FSB claim of alleged assassin fleeing to Estonia is provocation". ERR. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ ""Борются только с теми, кого боятся": Телеграм заблокировал канал рельсовых партизан в России" [“They fight only with those they are afraid of”: Telegram blocks the channel of rail guerrillas in Russia]. Апостроф (in Russian). Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Activatica". Activatica (in Russian). Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Роскомнадзор заблокировал сайт движения "Останови вагоны"" [Roskomnadzor blocks the website of the movement "Stop the Wagons"]. DOXA News. 18 July 2022. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Роскомнадзор заблокировал сайт движения "Останови вагоны"" [Roskomnadzor blocks the website of the "Stop the Wagons" movement]. The Village (in Russian). Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Telegram оштрафовали на 7 млн рублей за отказ удалить инструкции по проведению диверсий" [Telegram fined 7 million rubles for refusing to remove sabotage instructions]. ТАСС (in Russian). 16 August 2022.

- ^ "Moscow Court Fines Telegram, Twitch For Failing To Delete 'Illegal' Content". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Telegram fined for refusing to delete channel with sabotage instructions". TASS. Retrieved 26 August 2022.