DOx

4-Substituted-2,5-dimethoxyamphetamines (DOx) is a chemical class of substituted amphetamine derivatives featuring methoxy groups at the 2- and 5- positions of the phenyl ring, and a substituent such as alkyl or halogen at the 4- position of the phenyl ring.[1][2] They are 4-substituted derivatives of 2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine (2,5-DMA, DMA-4, or DOH).

Most compounds of this class are potent and long-lasting psychedelic drugs, and act as selective 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptor partial agonists. A few bulkier derivatives such as DOAM have similarly high binding affinity for 5-HT2 receptors but instead act as antagonists, and so do not produce psychedelic effects.[2]

Side effects

[edit]DOx drugs like DOM have been associated with concerning side effects that have not occurred to the same extent with other psychedelics like LSD.[3] Examples of such side effects include physical symptoms like sweating, tremors, and large increases in heart rate.[3]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]The DOx drugs act as agonists of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, including of the serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors.[4][5][6][2][7] Their psychedelic effects are thought to be mediated specifically by activation of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[5][2]

In contrast to other amphetamines, DOx drugs like DOC, DOET, and DOM are inactive as monoamine releasing agents and reuptake inhibitors.[8][9][4]

Some of the DOx drugs, including DOB, DOET, DOI, and DOM, are agonists of the rat, rhesus monkey, and/or human TAAR1.[10][11]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The DOx drugs are orally active and many have doses in the range of 1 to 10 mg and durations in the range of 8 to 30 hours.[12][7][2][13][3] Some DOx drugs, such as DOM and DOB, appear to have durations that increase non-linearly with dosage, for instance 8 hours at lower doses and as long as 30 hours or even up to 3 or 4 days at higher doses.[3][14] This suggests that the pathways mediating the metabolism of these drugs can saturate.[3] The DOx drugs are metabolized primarily by O-demethylation.[7] However, DOM is primarily metabolized by hydroxylation at its methyl group.[7]

History

[edit]DOM was the first psychedelic of the DOx series to be discovered.[15] It was first synthesized by Alexander Shulgin at Dow Chemical Company in 1963, who had had his first psychedelic experience, with mescaline (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine), in 1960.[15][3][16] Shulgin personally tried DOM on January 4, 1964 and discovered its psychedelic effects.[17][15][3][16] 2,4,5-Trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA-2; "DOMeO") had been synthesized by Bruckner in 1933, but its psychedelic effects were not described until Shulgin tried the compound and reported its effects in the scientific literature in 1964.[18][19][20] Prior to this, 3,4,5-trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA; α-methylmescaline) had been synthesized by Hey in 1947, being found by him to produce euphoria, and was described by Peretz and colleagues in 1955 as clearly producing psychedelic effects.[18][21][22][23]

Following his discovery of DOM, Shulgin developed DOET and found that at low doses it was a remarkable "psychic energizer" without producing psychedelic effects at these doses.[3] Dow Chemical Company decided to move forward with clinical trials of DOET as a potential pharmaceutical drug for such purposes.[3] Shulgin and Dow Chemical Company filed a patent for DOET in 1966, although it was not published until 1970.[3][15][24] Dow Chemical Company tasked Solomon H. Snyder at Johns Hopkins University with clinically studying DOET.[3]

In April 1967, following the banning of LSD in California in 1966, DOM emerged as a street drug and legal LSD alternative with the name "STP" (allegedly short for "Serenity, Tranquility, and Peace") in the Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco.[3][25] This occurred due to DOM being publicly distributed for free in the form of high-dose tablets by LSD distributor Owsley Stanley, who had personally learned of DOM from Shulgin.[3][25] It is unclear why Shulgin provided information about DOM to Stanley, since doing so had the potential to risk Shulgin's professional career and the DOET clinical studies.[3][25] One possibility is that Dow Chemical Company was not further looking into DOM and Shulgin thought that it was a promising drug that would otherwise be forgotten.[3] In any case, street use of DOM was short-lived because the tablets caused a public health crisis due to them often producing very long durations (up to 3–4 days), intense experiences, worrying physical side effects, and hospitalizations.[3] DOM was first reported on in the media and scientific literature in 1967 as a result of the crisis.[3][26][27] DOM became illegal in the United States in 1968.[3]

Dow Chemical Company terminated its clinical research program on DOET due to the DOM public health crisis.[3] DOET was subsequently first described in the literature by Snyder and colleagues in 1968.[27] Snyder continued to be interested in DOET as a potential medicine, but it was never further developed.[27] Snyder also described 2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine (2,5-DMA), which had been synthesized and tested by Shulgin, in the literature in 1968.[28] DOM and DOET were further described in the scientific literature by Shulgin in 1969.[29][15][3] In addition, Shulgin discussed DOM, DOET, TMA-2, and 2,5-DMA in a book chapter on hallucinogens published in 1970.[30]

The earlier DOx drugs like DOM and DOET were subsequently followed by DOB, which was developed by Shulgin and colleagues like Claudio Naranjo, in 1971,[15][31] and by DOI, DOC, and a few other analogues, which were developed by another research group, in 1973.[15][32] After this, numerous other DOx drugs were synthesized and characterized, both by Shulgin and other scientists.[18][33][14][13][16][34][2]

Following its discovery, DOI has become widely used in scientific research in the study of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors.[15][2]

List of DOx drugs

[edit]The DOx family includes the following members:

| Structure | Name | Abbreviation | CAS number |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2,5-Dimethoxyamphetamine | 2,5-DMA | 2801-68-5 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-amylamphetamine | DOAM | 63779-90-8 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine | DOB | 64638-07-9 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-butylamphetamine | DOBU | 63779-89-5 |

|

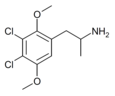

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine | DOC | 123431-31-2 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethoxyamphetamine | MEM | 16128-88-4 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(methoxymethyl)amphetamine | DOMOM [35] | 260810-10-4 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(ethoxymethyl)amphetamine | DOMOE | 930836-81-0 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine | DOET | 22004-32-6 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylthioamphetamine | Aleph-2 | 185562-00-9 |

|

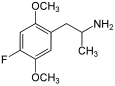

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-fluoroamphetamine | DOF | 125903-69-7 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(2-fluoroethyl)amphetamine | DOEF | 121649-01-2 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(3-fluoropropyl)amphetamine | DOPF | ? |

|

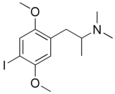

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine | DOI | 42203-78-1 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-isopropylthioamphetamine | Aleph-4 | 123643-26-5 |

|

2,4,5-Trimethoxyamphetamine | TMA-2 (DOMeO) | 1083-09-6 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine | DOM | 15588-95-1 |

|

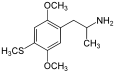

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methylthioamphetamine | Aleph-1 | 61638-07-1 |

|

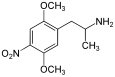

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-nitroamphetamine | DON | 67460-68-8 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-phenylthioamphetamine | Aleph-6 | 952006-44-9 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-benzylamphetamine | DOBZ [36] | 125903-73-3 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(3-methoxybenzyl)amphetamine | DO3MeOBZ [37] | 930836-90-1 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-[(tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)methyl]amphetamine | DOTHFM | 930776-12-8 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-propylamphetamine | DOPR | 63779-88-4 |

|

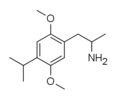

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-isopropylamphetamine | DOiP | 42306-96-7 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-propylthioamphetamine | Aleph-7 | 207740-16-7 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(difluoromethyl)amphetamine | DODFM | ? |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-trifluoromethylamphetamine | DOTFM | 159277-07-3 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)amphetamine | DOTFE [38] | ? |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-cyanoamphetamine | DOCN [39] | 125903-74-4 |

|

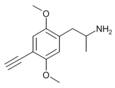

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethynylamphetamine | DOYN [40] | 633290-70-7 |

Related compounds

[edit]A number of additional compounds are known with alternative substitutions:

| Structure | Name | Abbreviation | CAS number |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dimoxamine ("Ariadne") | 4C-D | 52842-59-8 |

|

1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylphenyl)butan-2-amine [41] | 4C-E | |

|

1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(n-propyl)phenyl)butan-2-amine | 4C-P | |

|

1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-bromophenyl)butan-2-amine | 4C-B | 69294-23-1 |

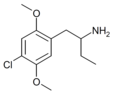

|

1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-chlorophenyl)butan-2-amine | 4C-C | 791010-74-7 |

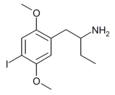

|

1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)butan-2-amine | 4C-I | 758631-75-3 |

|

1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-nitrophenyl)butan-2-amine | 4C-N | 775234-58-7 |

|

1-[2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(ethylthio)phenyl]butan-2-amine | 4C-T-2 | 850007-13-5 |

|

Dimethoxymethamphetamine ("Beatrice") | N-methyl-DOM | 92206-37-6 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine | DMMDA | 15183-13-8 |

|

2,5-dimethoxy-3,4-dimethylamphetamine ("Ganesha") | 3-methyl-DOM | 207740-37-2 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-3,4-trimethylenylamphetamine | G-3 | |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-3,4-tetramethylenylamphetamine | G-4 | |

|

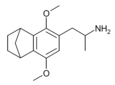

2,5-Dimethoxy-3,4-norbornylamphetamine | G-5 | |

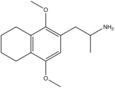

|

1-(5,8-dimethoxy-3,4-dihydro-1H-isochromen-7-yl)propan-2-amine [42] | G-O | 774538-38-4 |

|

2,5-Dimethoxy-3,4-dichloroamphetamine | DODC | 1373918-65-0 |

|

IDNNA | IDNNA | 67707-78-2 |

|

Methyl-DOB | N-methyl-DOB | 155638-80-5 |

|

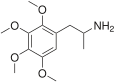

2,3,4,5-Tetramethoxyamphetamine | 2,3,4,5-Tetramethoxyamphetamine | 23693-26-7 |

|

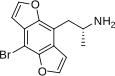

1-(4-Bromo-2,3,6,7-tetrahydrofuro[2,3-f][1]benzofuran-8-yl)propan-2-amine | DOB-FLY | 219986-75-1 |

|

Bromo-DragonFLY | DOB-DFLY | 502759-67-3 |

|

3-(4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)azetidine | Compound 1,[43] ZC-B |

See also

[edit]- 2,5-Dimethoxyamphetamine

- 2Cs, 25-NB

- Substituted amphetamines

- Substituted benzofurans

- Substituted cathinones

- Substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamines

- Substituted phenethylamines

- Substituted tryptamines

- PiHKAL

- The Shulgin Index

References

[edit]- ^ Daniel Trachsel; David Lehmann & Christoph Enzensperger (2013). Phenethylamine: Von der Struktur zur Funktion. Nachtschatten Verlag AG. ISBN 978-3-03788-700-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Glennon RA, Dukat M (June 2024). "1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane (DOI): From an Obscure to Pivotal Member of the DOX Family of Serotonergic Psychedelic Agents - A Review". ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 7 (6): 1722–1745. doi:10.1021/acsptsci.4c00157. PMC 11184610. PMID 38898956.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Baggott, Matthew J. (1 October 2023). "Learning about STP: A Forgotten Psychedelic from the Summer of Love" (PDF). History of Pharmacy and Pharmaceuticals. 65 (1): 93–116. doi:10.3368/hopp.65.1.93. ISSN 2694-3034. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- ^ a b Luethi, Dino; Rudin, Deborah; Hoener, Marius C.; Liechti, Matthias E. (2022). "Monoamine Receptor and Transporter Interaction Profiles of 4-Alkyl-Substituted 2,5-Dimethoxyamphetamines" (PDF). The FASEB Journal. 36 (S1). doi:10.1096/fasebj.2022.36.S1.R2691. ISSN 0892-6638.

- ^ a b Nichols, D.E.; Nichols, C. D. (2021). "The Pharmacology of Psychedelics". In Grob, C.S.; Grigsby, J. (eds.). Handbook of Medical Hallucinogens. Guilford Publications. pp. 3–28. ISBN 978-1-4625-4544-5. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

Phenylalkylamine hallucinogens such as DOM, DOI, and DOB are highly selective for 5-HT2 receptor subtypes (Pierce & Peroutka, 1989; Titeler, Lyon, & Glennon, 1988), and there is a consensus in the literature that the behavioral effects of psychedelics are primarily mediated by the 5-HT2A receptor (Halberstadt, 2015; Nichols, 2016).

- ^ Ray TS (February 2010). "Psychedelics and the human receptorome". PLOS ONE. 5 (2): e9019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009019. PMC 2814854. PMID 20126400.

- ^ a b c d Wills B, Erickson T (9 March 2012). "Psychoactive Phenethylamine, Piperazine, and Pyrrolidinophenone Derivatives". In Barceloux DG (ed.). Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. Wiley. pp. 156–192. doi:10.1002/9781118105955.ch10. ISBN 978-0-471-72760-6.

- ^ Eshleman AJ, Forster MJ, Wolfrum KM, Johnson RA, Janowsky A, Gatch MB (March 2014). "Behavioral and neurochemical pharmacology of six psychoactive substituted phenethylamines: mouse locomotion, rat drug discrimination and in vitro receptor and transporter binding and function". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 231 (5): 875–888. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3303-6. PMC 3945162. PMID 24142203.

- ^ Eshleman AJ, Wolfrum KM, Reed JF, Kim SO, Johnson RA, Janowsky A (December 2018). "Neurochemical pharmacology of psychoactive substituted N-benzylphenethylamines: High potency agonists at 5-HT2A receptors". Biochem Pharmacol. 158: 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2018.09.024. PMC 6298744. PMID 30261175.

- ^ Lewin AH, Miller GM, Gilmour B (December 2011). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a stereoselective binding site for compounds in the amphetamine class". Bioorg Med Chem. 19 (23): 7044–7048. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.007. PMC 3236098. PMID 22037049.

- ^ Bunzow JR, Sonders MS, Arttamangkul S, Harrison LM, Zhang G, Quigley DI, Darland T, Suchland KL, Pasumamula S, Kennedy JL, Olson SB, Magenis RE, Amara SG, Grandy DK (December 2001). "Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor". Mol Pharmacol. 60 (6): 1181–1188. doi:10.1124/mol.60.6.1181. PMID 11723224.

- ^ Ballentine G, Friedman SF, Bzdok D (March 2022). "Trips and neurotransmitters: Discovering principled patterns across 6850 hallucinogenic experiences". Sci Adv. 8 (11): eabl6989. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abl6989. PMC 8926331. PMID 35294242.

- ^ a b Jacob P, Shulgin AT (1994). "Structure-activity relationships of the classic hallucinogens and their analogs" (PDF). NIDA Res Monogr. 146: 74–91. PMID 8742795.

- ^ a b Shulgin, A.T.; Shulgin, A. (1991). PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. Transform Press. ISBN 978-0-9630096-0-9. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Canal CE, Morgan D (2012). "Head-twitch response in rodents induced by the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine: a comprehensive history, a re-evaluation of mechanisms, and its utility as a model". Drug Test Anal. 4 (7–8): 556–576. doi:10.1002/dta.1333. PMC 3722587. PMID 22517680.

- ^ a b c Shulgin, A.; Manning, T.; Daley, P.F. (2011). The Shulgin Index, Volume One: Psychedelic Phenethylamines and Related Compounds. Vol. 1. Berkeley: Transform Press. ISBN 978-0-9630096-3-0. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

A short history of DOM (STP) notes that the original synthesis took place in 1963, psychological effects were discovered the following year, and that the compound had appeared in the Haight-Ashbury scene of mid-1967 (Shulgin, 1977b). The known congeners of DOM were reviewed for structure-activity relationships (Barfknecht et al., 1978). [...] Shulgin, AT. (1977b) Profiles of psychedelic drugs. 5. STP. J. Psych. Drugs 9(2): 171-172.

- ^ "Alexander Theodore Shulgin (1925-2014)". openDemocracy. 9 June 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

[Shulgin's] attention was drawn to the 4-position after he conceived of and synthesized the compound DOM, which he bioassayed on January 4, 1964 and discovered to be surprisingly potent: it was psychoactive at the 1 mg dose.

- ^ a b c Shulgin AT (1978). "Psychotomimetic Drugs: Structure-Activity Relationships". In Iversen LL, Iversen SD, Snyder SH (eds.). Stimulants. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 243–333. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0510-2_6. ISBN 978-1-4757-0512-6.

3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenylisopropylamine (33, TMA, trimethoxyamphetamine) is the first psychotomimetic drug that evolved from the systematic application of the principles discovered in studying the relationships between chemical structure and biological activity. Armed with the known structure of mescaline, the proclivity of most phenethylamines to be of only fleeting activity centrally (due to facile deamination), and the effectiveness of a methyl group alpha- to the nitrogen as a stabilizing factor in central activity, Her (1947) synthesized TMA. His favorable impressions on the euphoric properties of the compound encouraged the Canadian group of Peretz and co-workers (1955) to explore its psychopharmacological nature and to evaluate its potential as a psychotomimetic. [...] 3.1.6. 2,4,5-Trimethoxyphenylisopropylamine This geometric isomer of TMA was first synthesized by Bruckner (1933) and its psychotomimetic properties were first observed some 30 years later (Shulgin, 1964a), 2,4,5-Trimethoxyphenylisopropylamine (34, TMA-2, 2,4,5-trimethoxyamphetamine) was the second of the six possible positional isomers found to be psychotomimetic, and was thus called TMA-2.

- ^ Bruckner, Viktor (24 October 1933). "Über das Pseudonitrosit des Asarons". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 138 (9–10): 268–274. doi:10.1002/prac.19331380907. ISSN 0021-8383.

- ^ Shulgin AT (July 1964). "Psychotomimetic amphetamines: methoxy 3,4-dialkoxyamphetamines". Experientia. 20 (7): 366–367. doi:10.1007/BF02147960. PMID 5855670.

- ^ Peretz DI, Smythies JR, Gibson WC (April 1955). "A new hallucinogen: 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl-beta-aminopropane with notes on the stroboscopic phenomenon". J Ment Sci. 101 (423): 317–329. doi:10.1192/bjp.101.423.317. PMID 13243046.

3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl-β-aminopropane (Trimethoxyamphetamine, TMA) was first synthesized by Hey in 1947 (Hey, 1947) who was impressed with its euphoric properties (private communication). [...]

- ^ Shulgin, Alexander T.; Bunnell, Sterling; Sargent, Thornton (1961). "The Psychotomimetic Properties of 3,4,5-Trimethoxyamphetamine". Nature. 189 (4769): 1011–1012. doi:10.1038/1891011a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Hey P (1947). "The synthesis of a new homologue of mescaline". Q J Pharm Pharmacol. 20 (2): 129–134. PMID 20260568.

- ^ "phenethylamines and their pharmacologically-acceptable salts". Google Patents. 1970. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- ^ a b c Trout K, Daley PF (December 2024). "The origin of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM, STP)". Drug Test Anal. 16 (12): 1496–1508. doi:10.1002/dta.3667. PMID 38419183.

- ^ Snyder SH, Faillace L, Hollister L (November 1967). "2,5-dimethoxy-4-methyl-amphetamine (STP): a new hallucinogenic drug". Science. 158 (3801): 669–670. doi:10.1126/science.158.3801.669. PMID 4860952.

- ^ a b c Snyder SH, Faillace LA, Weingartner H (September 1968). "DOM (STP), a new hallucinogenic drug, and DOET: effects in normal subjects". Am J Psychiatry. 125 (3): 113–120. doi:10.1176/ajp.125.3.357. PMID 4385937.

- ^ Snyder SH, Richelson E (May 1968). "Psychedelic drugs: steric factors that predict psychotropic activity". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 60 (1): 206–213. doi:10.1073/pnas.60.1.206. PMC 539103. PMID 5241523.

Shulgin (personal communication) has synthesized 2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine (2,5-DMA) (Fig. 4) and observed its potency in man as between 8 and 10 MU. This compound corresponds to TMA-2 with the absence of the methoxy at C-4. 2,5-DMA is considerably more potent than TMA, TMA-3, or TMA-4, all of which have three methoxy groupings. [...]

- ^ Shulgin, Alexander T. (1969). "Psychotomimetic Agents Related to the Catecholamines". Journal of Psychedelic Drugs. 2 (2): 14–19. doi:10.1080/02791072.1969.10524409. ISSN 0022-393X.

- ^ Alexander Shulgin (1970). "Chemistry and Structure-Activity Relationships of the Psychotomimetics". In D. H. Efron (ed.). Psychotomimetic Drugs (PDF). New York: Raven Press. pp. 21–41.

- ^ Shulgin AT, Sargent T, Naranjo C (1971). "4-Bromo-2,5-dimethoxyphenylisopropylamine, a new centrally active amphetamine analog". Pharmacology. 5 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1159/000136181. PMID 5570923.

- ^ Coutts, Ronald T.; Malicky, Jerry L. (1 May 1973). "The Synthesis of Some Analogs of the Hallucinogen 1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methylphenyl)-2-aminopropane (DOM)". Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 51 (9): 1402–1409. doi:10.1139/v73-210. ISSN 0008-4042. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- ^ Nichols DE, Glennon RA (1984). "Medicinal Chemistry and Structure-Activity Relationships of Hallucinogens" (PDF). Hallucinogens: Neurochemical, Behavioral, and Clinical Perspectives. pp. 95–142.

- ^ Nichols DE (2018). "Chemistry and Structure-Activity Relationships of Psychedelics". Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 36: 1–43. doi:10.1007/7854_2017_475. PMID 28401524.

- ^ Harms A, Ulmer E, Kovar K. Synthesis and 5-HT2A radioligand receptor binding assays of DOMCl and DOMOM, two novel 5-HT2A receptor ligands. Arch. Pharm., 16 Jun 2003, 336(3): 155–158. doi:10.1002/ardp.200390014

- ^ Nelson DL, Lucaites VL, Wainscott DB, Glennon RA. Comparisons of hallucinogenic phenylisopropylamine binding affinities at cloned human 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors. N-S. Arch. Pharmacol., 1 Jan 1999, 359(1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/PL00005315

- ^ Hellberg M, Namil A, Feng Z, Ward J. Phenylethylamine Analogs and Their Use for Treating Glaucoma. Patent WO 2007/038372, 6 Apr 2007

- ^ Trachsel D. Fluorine in psychedelic phenethylamines. Drug Test. Anal., 1 Jul 2012, 4(7-8): 577-590.doi:10.1002/dta.413

- ^ Seggel MR, Yousif MY, Lyon RA, Titeler M, Roth BL, Suba EA, Glennon, RA. A structure-affinity study of the binding of 4-substituted analogues of 1-(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-aminopropane at 5-HT2 serotonin receptors. J. Med. Chem., 1 Mar 1990, 33(3): 1032–1036. doi:10.1021/jm00165a023

- ^ Trachsel D (August 2003). "Synthesis of Novel (Phenylalkyl) amines for the Investigation of Structure–Activity Relationships, Part 3: 4-Ethynyl-2,5-dimethoxyphenethylamine (= 4-Ethynyl-2, 5-dimethoxybenzeneethanamine; 2C-YN)". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 86 (8): 2754–9. doi:10.1002/hlca.200390224.

- ^ Shulgin AT. Treatment of senile geriatric patients to restore performance. Patent US 4034113

- ^ Hellberg MR, Namil A. Benzopyran analogs and their use for the treatment of glaucoma. Patent US 7396856

- ^ Kristensen J, et al. 5-HT2A Agonists for Use in Treatment of Depression. Patent US 2021/0137908