Sardinia

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (August 2022) |

Sardinia

| |

|---|---|

| Autonomous Region of Sardinia | |

|

| |

| Anthem: "Su patriotu sardu a sos feudatarios" (Sardinian) (English: "The Sardinian Patriot to the Lords") | |

| Coordinates: 40°N 9°E / 40°N 9°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Capital | Cagliari |

| Government | |

| • Type | Consiglio Regionale |

| • President | Alessandra Todde (M5S) |

| Area | |

• Total | 24,090 km2 (9,300 sq mi) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 1,628,384 |

| • Density | 68/km2 (180/sq mi) |

| • Languages | Italian and Sardinian |

| • Minority languages | |

| [1] | |

| Demonyms | |

| Citizenship | |

| • Italian | 97% |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €35.032 billion (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IT-88 |

| HDI (2021) | 0.871[4] very high · 16th of 21 |

| NUTS Region | ITG |

| Website | www |

Sardinia (/sɑːrˈdɪniə/ sar-DIN-ee-ə; Italian: Sardegna [sarˈdeɲɲa]; Sardinian: Sardigna [saɾˈdiɲːa])[a][b] is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia and 16.45 km[5] south of the French island of Corsica.

It is one of the five Italian regions with some degree of domestic autonomy being granted by a special statute.[6] Its official name, Autonomous Region of Sardinia, is bilingual in Italian and Sardinian: Regione Autonoma della Sardegna / Regione Autònoma de Sardigna.[7] It is divided into four provinces and a metropolitan city. The capital of the region of Sardinia — and its largest city — is Cagliari.

Sardinia's indigenous language and Algherese Catalan are referred to by both the regional and national law as two of Italy's twelve officially recognized linguistic minorities,[8] albeit gravely endangered, while the regional law provides some measures to recognize and protect the aforementioned as well as the island's other minority languages (the Corsican-influenced Sassarese and Gallurese, and finally Tabarchino Ligurian).[9][10]

Owing to the variety of Sardinia's ecosystems, which include mountains,[11] woods, plains, stretches of largely uninhabited territory, streams, rocky coasts, and long sandy beaches,[12] Sardinia has been metaphorically described as a micro-continent.[13] In the modern era, many travelers and writers have extolled the beauty of its long-untouched landscapes, which retain vestiges of the Nuragic civilization.[14]

Etymology

[edit]The name Sardinia has pre-Latin roots. It comes from the pre-Roman ethnonym *s(a)rd-, later romanised as sardus (feminine sarda). It makes its first appearance on the Nora Stone, where the word ŠRDN, or *Šardana, testifies to the name's existence when the Phoenician merchants first arrived.[15]

According to Timaeus, one of Plato's dialogues, Sardinia (referred to by most ancient Greek authors as Sardṓ, Σαρδώ) and its people as well might have been named after a legendary woman called Sardṓ (Σαρδώ), born in Sardis (Σάρδεις), capital of the ancient Kingdom of Lydia.[16][17] There has also been speculation that identifies the ancient Nuragic Sards with the Sherden, one of the Sea Peoples.[18][19][20][21][22] It is suggested that the name had a religious connotation from its use also as the adjective for the ancient Sardinian mythological hero-god Sardus Pater[23] ("Sardinian Father"; a common explanation that the term means "Father of the Sardinians" is incorrect, as that would be "Sardorum Pater"), as well as being the stem of the adjective "sardonic".

In classical antiquity, Sardinia was called a number of names besides Sardṓ (Σαρδώ) or Sardinia, like Ichnusa (the Latinised form of the Greek Ἰχνοῦσσα),[24] Sandaliotis (Σανδαλιῶτις[25]) and Argyrophleps (Αργυρόφλεψ).[26]

Geography

[edit]

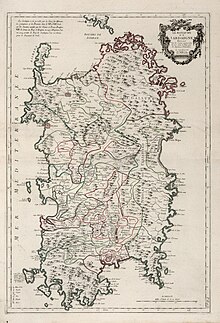

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea (after Sicily and before Cyprus), with an area of 24,100 km2 (9,305 sq mi). It is situated between 38° 51' and 41° 18' latitude north (respectively Isola del Toro and Isola La Presa) and 8° 8' and 9° 50' east longitude (respectively Capo dell'Argentiera and Capo Comino). To the west of Sardinia is the Sea of Sardinia, a unit of the Mediterranean Sea; to Sardinia's east is the Tyrrhenian Sea, which is also an element of the Mediterranean Sea.[27]

The nearest land masses are (clockwise from north) the island of Corsica, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Tunisia, the Balearic Islands, and Provence. The Tyrrhenian Sea portion of the Mediterranean Sea is directly to the east of Sardinia between the Sardinian east coast and the west coast of the Italian mainland peninsula. The Strait of Bonifacio is directly north of Sardinia and separates Sardinia from the French island of Corsica.

The coast of Sardinia is 1,849 km (1,149 mi) long. It is generally high and rocky, with long, relatively straight stretches, outstanding headlands, wide, deep bays, rias, and inlets with various smaller islands.

The island has an ancient geoformation and, unlike Sicily and mainland Italy, is not earthquake-prone. Its rocks date in fact from the Palaeozoic Era. The Cambrian-Lower Ordovician succession of Sardinia reaches 1500–3000 m in thickness.[28] Due to long erosion processes, the island's highlands, formed of granite, schist, trachyte, basalt (called jaras or gollei), sandstone and dolomite limestone (called tonneri or 'heels'), average at between 300 and 1,000 m (984 and 3,281 ft). The highest peak is Punta La Marmora (Perdas Carpìas in Sardinian language) (1,834 m (6,017 ft)), part of the Gennargentu Ranges in the centre of the island. Other mountain chains are Monte Limbara (1,362 m (4,469 ft)) in the northeast, the Chain of Marghine and Goceano (1,259 m (4,131 ft)) running crosswise for 40 km (25 mi) towards the north, the Monte Albo (1,057 m (3,468 ft)), the Sette Fratelli Range in the southeast, and the Sulcis Mountains and the Monte Linas (1,236 m (4,055 ft)). The island's ranges and plateaux are separated by wide alluvial valleys and flatlands, the main ones being the Campidano in the southwest between Oristano and Cagliari and the Nurra in the northwest.

Sardinia has few major rivers, the largest being the Tirso, 151 km (94 mi) long, which flows into the Sea of Sardinia, the Coghinas (115 km (71 mi)) and the Flumendosa (127 km (79 mi)). There are 54 artificial lakes and dams that supply water and electricity. The main ones are Lake Omodeo and Lake Coghinas. The only natural freshwater lake is Lago di Baratz. A number of large, shallow, salt-water lagoons and pools are located along the coast.

Climate

[edit]

The climate of the island is variable from area to area, due to several factors including the extension in latitude and the elevation. It can be classified in two different macrobioclimates (Mediterranean pluviseasonal oceanic and Temperate oceanic), one macrobioclimatic variant (Submediterranean), and four classes of continentality (from weak semihyperoceanic to weak semicontinental), eight thermotypic horizons (from lower thermomediterranean to upper supratemperate), and seven ombrotypic horizons (from lower dry to lower hyperhumid), resulting in a combination of 43 different isobioclimates.[29]

During the year there is a major concentration of rainfall in the winter and autumn, some heavy showers in the spring and snowfalls in the highlands. The average temperature is between 11 and 18 °C (52 and 64 °F), with mild winters and warm summers on the coasts (9 to 16 °C (48 to 61 °F) in January, 23 to 31 °C (73 to 88 °F) in July), and cold winters and cool summers on the mountains (−2 to 4 °C (28 to 39 °F) in January, 16 to 20 °C (61 to 68 °F) in July).

Rainfall has a Mediterranean distribution all over the island, with almost totally rainless summers and wet autumns, winters and springs. However, in summer, the rare rainfalls can be characterized by short but severe thunderstorms, which can cause flash floods. The climate is also heavily influenced by the vicinity of the Gulf of Genoa (barometric low) and the relative proximity of the Atlantic Ocean. Low pressures in autumn can generate the formation of the so-called Medicanes, extratropical cyclones which affect the Mediterranean basin. In 2013, the island was hit by several cyclones, included the Cyclone Cleopatra, which dumped 450 mm (18 in) of rainfall within an hour and a half.[30]

Sardinia being relatively large and hilly, weather is not uniform; in particular the East is drier, but paradoxically it suffers the worst rainstorms: in autumn 2009, it rained more than 200 mm (7.9 in) in a single day in Siniscola, and 19 November 2013, locations in Sardinia were reported to have received more than 431 mm (17.0 in) within two hours. The western coast has a higher distribution of rainfalls even for modest elevations (for instance Iglesias, elevation 200 m (656 ft), average annual precipitation 815 mm (32.1 in)). The driest part of the island is the coast of Cagliari gulf, with less than 450 mm (17.7 in) per year, the minimum is at Capo Carbonara at the extreme south-east of the island 381 mm (15.0 in),[31] and the wettest is the top of the Gennargentu mountain with almost 1,500 mm (59.1 in) per year. The average for the entire island is about 800 mm (31.5 in) per year, which is more than enough for the needs of the population and vegetation.[32] The Mistral from the northwest is the dominant wind on and off throughout the year, though it is most prevalent in winter and spring. It can blow quite strongly, but it is usually dry and cool.

| Climate data for Cagliari, altitude 4 m (13 ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

22.9 (73.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.8 (87.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.5 (41.9) |

5.8 (42.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.6 (67.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 49.7 (1.96) |

53.3 (2.10) |

40.4 (1.59) |

39.7 (1.56) |

26.1 (1.03) |

11.9 (0.47) |

4.1 (0.16) |

7.5 (0.30) |

34.9 (1.37) |

52.6 (2.07) |

58.4 (2.30) |

48.9 (1.93) |

427.5 (16.83) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 4.4 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 61.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 136.4 | 139.2 | 186.0 | 213.0 | 269.7 | 288.0 | 334.8 | 310.0 | 246.0 | 198.4 | 147.0 | 127.1 | 2,595.6 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico,[33] Hong Kong Observatory[34] for data of sunshine hours | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Fonni, altitude 1029 m | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 97 (3.8) |

118 (4.6) |

110 (4.3) |

88 (3.5) |

73 (2.9) |

33 (1.3) |

11 (0.4) |

18 (0.7) |

40 (1.6) |

93 (3.7) |

107 (4.2) |

131 (5.2) |

919 (36.2) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.9 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 10.5 | 7.4 | 4.2 | — | 2.4 | 4.8 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 88.6 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]

Sardinia has been inhabited by humans since the end of the Paleolithic era, around 20–10,000 years ago. The island's most notable civilization is the indigenous Nuragic, which flourished from the 18th century BC to either 238 BC or the 2nd century AD in some parts of the island,[35] and to the 6th century AD in that part of the island known as Barbagia.[36][37][38]

After a period in which the island was ruled by a political and economic alliance between the Nuragic Sardinians and the Phoenicians, parts of it were conquered by Carthage in the late 6th century BC, and by Rome in 238 BC. The Roman occupation lasted for 700 years.

Beginning in the Early Middle Ages, the island was ruled by the Vandals and the Byzantines. In practice, the island was disconnected from Byzantium's territorial influence, which allowed the Sardinians to provide themselves with a self-ruling political organization, the four kingdoms known as Judicates. The Italian maritime republics of Pisa and Genoa struggled to impose political control over these indigenous kingdoms, but it was the Iberian Crown of Aragon which, in 1324, succeeded in bringing the island under its control, consolidating it into the Kingdom of Sardinia.

This Iberian kingdom endured until 1718, when it was ceded to the Alpine House of Savoy; the Savoyards would politically merge their insular possession with their domains on the Italian Mainland which, during the period of Italian unification, they would go on to expand to include the whole Italian peninsula; their territory was so renamed into the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, and it was reconstituted as the present-day Italian Republic in 1946.

Prehistory

[edit]

Sardinia is one of the most geologically ancient bodies of land in Europe. The island was populated in various waves of immigration from prehistory until recent times.

Remains from Corbeddu Cave in eastern Sardinia have been suggested by some authors to represent the earliest evidence of human presence on Sardinia, around 20,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum. However, other authors contend that there is no solid evidence for the occupation of the island until the early Mesolithic, around 10,000 years ago.[39]

The Neolithic began on Sardinia during the 6th millennium BC resulting from the migration of Early European Farmers, replacing the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer populations, with a material culture including the widespread Cardium pottery style.[40][41] In the mid-Neolithic period, the Ozieri culture, probably of Aegean origin, flourished on the island spreading the hypogeum tombs known as domus de Janas, while the Arzachena culture of Gallura built the first megaliths: circular tombs. In the early 3rd millennium BC, the metallurgy of copper and silver began to develop.

During the late Chalcolithic the so-called Beaker culture, coming from various parts of Continental Europe, appeared in Sardinia. These new people predominantly settled on the west coast, where the majority of the sites attributed to them had been found.[42] The Beaker culture was followed in the early Bronze Age by the Bonnanaro culture which showed both reminiscences of the Beaker and influences by the Polada culture.

As time passed the different Sardinian populations appear to have become united in customs, yet remained politically divided into various small, tribal groupings, at times banding together against invading forces from the sea, and at others waging war against each other. Habitations consisted of round thatched stone huts.

Nuragic civilization

[edit]From about 1500 BC onwards, villages were built around a kind of round tower-fortress called nuraghe[43] (usually pluralized as nuraghes in English and as nuraghi in Italian). These towers were often reinforced and enlarged with battlements. Tribal boundaries were guarded by smaller lookout Nuraghes erected on strategic hills commanding a view of other territories.

Today, some 7,000 Nuraghes dot the Sardinian landscape. While initially these Nuraghes had a relatively simple structure, with time they became extremely complex and monumental (see for example the Nuraghe Santu Antine, Su Nuraxi, or Nuraghe Arrubiu). The scale, complexity and territorial spread of these buildings attest to the level of wealth accumulated by the Nuragic Sardinians, their advances in technology and the complexity of their society, which was able to coordinate large numbers of people with different roles for the purpose of building the monumental Nuraghes.

The Nuraghes are not the only Nuragic buildings that stand in place, as there are several sacred wells around Sardinia and other buildings with religious purposes such as the Giants' grave (monumental collective tombs) and collections of religious buildings that probably served as destinations for pilgrimage and mass religious rites (e.g. Su Romanzesu near Bitti).

At the time, Sardinia was at the centre of several commercial routes and it was an important provider of raw materials such as copper and lead, which were pivotal for the manufacture of the time. By controlling the extraction of these raw materials and by trading them with other countries, the ancient Sardinians were able to accumulate wealth and reach a level of sophistication that is not only reflected in the complexity of its surviving buildings, but also in its artworks (e.g. the votive bronze statuettes found across Sardinia or the statues of Mont'e Prama).

According to some scholars, the Nuragic people(s) are identifiable with the Sherden, a tribe of the Sea Peoples.[44][35]

The Nuragic civilization was linked with other contemporaneous megalithic civilization of the western Mediterranean, such as the Talaiotic culture of the Balearic Islands and the Torrean civilization of Southern Corsica. Evidence of trade with the other civilizations of the time is attested by several artefacts (e.g. pots), coming from as far as Cyprus, Crete, Mainland Greece, Spain and Italy, that have been found in Nuragic sites, bearing witness to the scope of commercial relations between the Nuragic people and other peoples in Europe and beyond.

Ancient history

[edit]

Around the 9th century BC the Phoenicians began visiting Sardinia with increasing frequency, presumably initially needing safe overnight and all-weather anchorages along their trade routes from the coast of modern-day Lebanon as far afield as the African and European Atlantic coasts and beyond. The most common ports of call were Caralis, Nora, Bithia, Sulci, and Tharros. Claudian, a 4th-century Latin poet, in his poem De bello Gildonico, stated that Caralis was founded by people from Tyre, probably in the same time of the foundation of Carthage, in the 9th or 8th century BC.[45] In the 6th century BC, after the conquest of western Sicily, the Carthaginians planned to annex Sardinia.[46] A first invasion attempt led by Malchus was foiled by the victorious Nuraghic resistance. However, from 510 BC, the southern and west-central part of the island were invaded a second time and came under Carthaginian rule.[46][47]

In 238 BC, taking advantage of Carthage having to face a rebellion of her mercenaries (the Mercenary War) after the First Punic War (264–241 BC), the Romans annexed Corsica and Sardinia from the Carthaginians. The two islands became the province of Corsica and Sardinia. They were not given a provincial governor until 227 BC. The Romans faced many rebellions, and it took them many years to pacify both islands. The existing coastal cities were enlarged and embellished, and Roman colonies such as Turris Lybissonis and Feronia were founded. These were populated by Roman immigrants. The Roman military occupation brought the Nuragic civilization to an end, except for the mountainous interior of the island, which the Romans called Barbaria, meaning 'Barbarian land'. Roman rule in Sardinia lasted 694 years, during which time the province was an important source of grain for the capital. Latin came to be the dominant spoken language during this period, though Roman culture was slower to take hold, and Roman rule was often contested by the Sardinian tribes from the mountainous regions.[48]

Vandal conquest

[edit]

The east Germanic tribe of the Vandals conquered Sardinia in 456. Their rule lasted for 78 years up to 534, when 400 eastern Roman troops led by Cyril, one of the officers of the foederati, retook the island. It is known that the Vandal government continued the forms of the existing Roman Imperial structure. The governor of Sardinia continued to be called the praeses and apparently continued to manage military, judicial, and civil governmental functions via imperial procedures. The only Vandal governor of Sardinia about whom there is substantial record is the last, Godas, a Visigoth noble. In AD 530, a coup d'état in Carthage removed King Hilderic, a convert to Nicene Christianity, in favor of his cousin Gelimer, an Arian Christian like most of the elite in his kingdom. Godas was sent to take charge and ensure the loyalty of Sardinia. He did the exact opposite, declaring the island's independence from Carthage[49] and opening negotiations with Emperor Justinian I, who had declared war on Hilderic's behalf. In AD 533, Gelimer sent the bulk of his army and navy (120 vessels and 5,000 men) to Sardinia to subdue Godas, with the catastrophic result that the Vandal Kingdom was overwhelmed when Justinian's own army under Belisarius arrived at Carthage in their absence. The Vandal Kingdom ended and Sardinia was returned to Roman rule.[50]

Byzantine era and the rise of the Judicates

[edit]In 533, Sardinia returned to the rule of the Byzantine Empire when the Vandals were defeated by the armies of Justinian I under the General Belisarius in the Battle of Tricamarum, in their African kingdom Belisarius sent his general Cyril to Sardinia to retake the island. Sardinia remained in Byzantine hands for the next 300 years[51] aside from a short period in which it was invaded by the Ostrogoths in 551.

Under Byzantine rule, the island was divided into districts called mereíai (μερείαι) in Byzantine Greek, which were governed by a judge residing in Caralis and garrisoned by an army stationed in Forum Traiani (today Fordongianus) under the command of a dux.[52] During this time, Christianity took deeper root on the island, supplanting the Paganism which had survived into the early Middle Ages in the culturally conservative hinterlands. Along with lay Christianity, the followers of monastic figures such as Basil of Caesarea became established in Sardinia. While Christianity penetrated the majority of the population, the region of Barbagia remained largely pagan and, probably, partially non-Latin speaking. They re-established a short-lived independent domain with Sardinian-heathen lay and religious traditions, one of its kings being Hospito.[53][54] Pope Gregory I wrote a letter to Hospito defining him "Dux Barbaricinorum" and, being Christian, the leader and best of his people.[55] In this unique letter about Hospito, the Pope prompts him to convert his people who "living all like irrational animals, ignore the true God and worship wood and stone" (Barbaricini omnes, ut insensata animalia vivant, Deum verum nesciant, ligna autem et lapides adorent).[56]

The dates and circumstances of the end of Byzantine rule in Sardinia are not known. Direct central control was maintained at least through c. 650, after which local legates were empowered in the face of the rebellion of Gregory the Patrician, Exarch of Africa and the first invasion of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb. There is some evidence that senior Byzantine administration in the Exarchate of Africa retreated to Caralis following the final fall of Carthage to the Arabs in 697.[57] The loss of imperial control in Africa led to escalating raids by Arabs on the island, the first of which is documented in 703, forcing increased military self-reliance in the province.[58]

Elsewhere in the central Mediterranean, the Aghlabids conquered the island of Malta in 870.[59]: 208 They also attacked or raided Sardinia and Corsica.[60][61]: 153, 244 Some modern references state that Sardinia came under Aghlabid control around 810 or after the beginning of the conquest of Sicily in 827.[62][63][64][65] Historian Corrado Zedda argues that the island hosted a Muslim presence during the Aghlabid period, possibly a limited foothold along the coasts that forcibly coexisted with the local Byzantine government.[66] Historian Alex Metcalfe argues that the available evidence for any Muslim occupation or colonisation of the island during this period is limited and inconclusive, and that Muslim attacks were limited to raids.[61]

Communication with the central government became daunting if not impossible during and after the Muslim conquest of Sicily between 827 and 902. A letter by Pope Nicholas I as early as 864 mentions the "Sardinian judges",[67] without reference to the empire and a letter by Pope John VIII (reigned 872–882) refers to them as principes ("princes"). By the time of De Administrando Imperio, completed in 952, the Byzantine authorities no longer listed Sardinia as an imperial province, suggesting they considered it lost.[57] In all likelihood a local noble family, the Lacon-Gunale, acceded to the power of Archon, still identifying themselves as vassals of the Byzantines, but de facto independent as communications with Constantinople were very difficult. Only two names of those rulers are known: Salusios (Σαλούσιος) and the protospatharios Turcoturios (Tουρκοτούριος) from two inscriptions),[68][69][70] who probably reigned between the 10th and the 11th century. These rulers were still closely linked to the Byzantines, both for a pact of ancient vassalage,[71] and from the ideological point of view, with the use of the Byzantine Greek language (in a Romance country), and the use of art of Byzantine inspiration.

In the early 11th century, an attempt to conquer the island was made by Mujahid al-Amiri al-Ṣaqlabī was the ruler of Dénia and the Balearic Islands based in the Iberian Peninsula.[72] The only records of that war are from Pisan and Genoese chronicles.[73] The Christians won but, after that, the previous Sardinian kingdom was undermined and subsequently divided into four smaller states: Cagliari (Calari), Arborea (Arbaree), Gallura, and Torres or Logudoro.

Whether this final transformation from imperial civil servant to independent sovereign bodies resulted from imperial abandonment or local assertion, by the 10th century, the so-called "Judges" (Sardinian: judikes / Latin: iudices, a Byzantine administrative title) had emerged as the autonomous rulers of Sardinia. The title of iudice changed with the language and local understanding of the position, becoming the Sardinian judike, essentially a king or sovereign, while Judicate (Sardinian: logu) came to mean 'state'.[74]

Early medieval Sardinian political institutions evolved from the millennium-old Roman imperial structures with relatively little Germanic influence.

Although the Judicates were hereditary lordships, the old Byzantine imperial notion that personal title or honor was separate from the state still remained, so the Judicate was not regarded as the personal property of the monarch as was common in later European feudalism. Like the imperial systems, the new order also preserved "semi-democratic" forms, with national assemblies called the Crown of the Realm. Each Judicate saw to its own defense, maintained its own laws and administration, and looked after its own foreign and trading affairs.[75]

The history of the four Judicates would be defined by the contest for influence between the two Italian maritime powers of Genoa and Pisa, and later the ambitions of the Kingdom of Aragon.

The Judicate of Cagliari or Pluminos, during the regency of Torchitorio V of Cagliari and his successor, William III, was allied with the Republic of Genoa. Because of this it was brought to an end in 1258, when its capital, Santa Igia, was stormed and destroyed by an alliance of Sardinian and Pisan forces. The territory then was divided between the Republic of Pisa, the Della Gherardesca family from Italy, and the Sardinian Judicates of Arborea and Gallura. Pisa maintained the control over the fortress of Castel di Cagliari founded by Pisan merchants in 1216–1217 east of Santa Igia;[76] in the south-west the count Ugolino della Gherardesca promoted the birth of the town of Villa di Chiesa (today Iglesias) to exploit the nearby rich silver deposits.[77]

The Judicate of Logudoro (also called Torres) was also allied to the Republic of Genoa and came to an end in 1259 after the death of the judikessa (queen) Adelasia. The territory was divided up between the Doria and Malaspina families of Genoa and the Bas-Serra family of Arborea, while the city of Sassari became a small republic, along the lines of the Italian city-states (comuni), confederated firstly with Pisa and then with Genoa.[78]

The Judicate of Gallura ended in the year 1288, when the last giudice, Nino Visconti (a friend of Dante Alighieri), was driven out by the Pisans, who occupied the territory.[79]

The Judicate of Arborea, having Oristano as its capital, had the longest life compared to the other kingdoms. Its later history is entwined with the attempt to unify the island into a single Sardinian state (Republica sardisca 'Sardinian Republic' in Sardinian, Nació sarda or sardesca 'Sardinian Nation' in Catalan) against their relatives and former Aragonese allies.

Aragonese period

[edit]In 1297, Pope Boniface VIII established on his own initiative (motu proprio) a hypothetical regnum Sardiniae et Corsicae ("Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica") in order to settle the War of the Sicilian Vespers diplomatically. This had broken out in 1282 between the Capetian House of Anjou and Aragon over the possession of Sicily. Despite the existence of the indigenous states, the Pope offered this newly created crown to James II of Aragon, promising him support should he wish to conquer Pisan Sardinia in exchange for Sicily.

In 1324, in alliance with the Kingdom of Arborea[80] and following a military campaign that lasted a year or so, the Aragon Crown Prince Alfonso led an Aragonese army that occupied the Pisan territories of Cagliari and Gallura along with the allied city of Sassari, naming them "The Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica". The kingdom was to remain a dominion of the Crown of Aragon (under the 16th-century kings of Spain) until the Peace of Utrecht.

During this period, the Judicate of Arborea promulgated the legal code of the kingdom in the Carta de Logu ('Charter of the Land'). The Carta de Logu was originally compiled by Marianus IV of Arborea, and was amended and updated by Mariano's daughter, Female Judge (judikessa or juighissa) Eleanor of Arborea. The legal code was written in Sardinian and established a whole range of citizens' rights. Among the revolutionary concepts in this Carta de Logu was the right of women to refuse marriage and to own property. In terms of civil liberties, the code made provincial 14th century Sardinia one of the most developed societies in all of Europe.[81]

In 1353, Peter IV of Aragon, following Aragonese customs, granted a parliament to the kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica, which was followed by some degree of self-government under a viceroy and judicial independence. This parliament, however, had limited powers. It consisted of high-ranking military commanders, the clergy and the nobility. The kingdom of Aragon also introduced the feudal system into the areas of Sardinia that it ruled.

The Sardinian Judicates never adopted feudalism, and Arborea maintained its parliament, called the Corona de Logu 'Crown of the Realm'. In this parliament, apart from the nobles and military commanders, also sat the representatives of each township and village. The Corona de Logu exercised some control over the king: under the rule of the bannus consensus the king could be deposed or even executed if he did not follow the rules of the kingdom.

Having broken the alliance with the Crown of Aragon, from 1353[82] to 1409, the Arborean giudici Marianus IV, Hugh III and Brancaleone Doria (husband of Eleanor of Arborea), succeeded in occupying all of Sardinia except the heavily fortified towns of the Castle of Cagliari and Alghero, which for years remained as the only Aragonese dominions in Sardinia (Sardinian–Aragonese war).

In 1409, Martin I of Sicily, king of Sicily and heir to the crown of Aragon, defeated the Sardinians at the Battle of Sanluri. The battle was fought by about 20,000 Sardinian, Genoese and French knights, enrolled from their kingdom at a time when the population of Sardinia had been greatly depleted by the plague. Despite the Sardinian army outnumbering the Aragonese army, they were defeated.

The Judicate of Arborea disappeared in 1420, when its rights were sold by the last king for 100,000 gold florins,[83] and after some of its most notable men switched sides in exchange for privileges. For example, Leonardo Cubello, with some claim to the crown being from a family related to the Kings of Arborea, was granted the title of Marquis of Oristano and feudal rights on a territory that partly overlapped with the original extension of the Kingdom of Arborea in exchange for his subjection to the Aragonese monarchs.

The conquest of Sardinia by the Kingdom of Aragon meant the introduction of the feudal system throughout Sardinia. Thus Sardinia is probably the only European country where feudalism was introduced in the transition period from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, at a time when feudalism had already been abandoned by many other European countries.

Spanish period

[edit]

In 1469, the heir to Sardinia, Ferdinand II of Aragon, married Isabel of Castile, and the "Kingdom of Sardinia" (which was separated from Corsica) was to be inherited by their Habsburg grandson, Charles I of Spain, with the state symbol of the Four Moors. The successors of Charles I of Spain, in order to defend their Mediterranean territories from raids of the Barbary pirates, fortified the Sardinian shores with a system of coastal lookout towers, allowing the gradual resettlement of some coastal areas.

The Kingdom of Sardinia remained Aragonese-Spanish for about 400 years, from 1323 to 1708, assimilating a number of Spanish traditions, customs and linguistic expressions, nowadays vividly portrayed in the folklore parades of Saint Efisio in Cagliari (1 May), the Cavalcade on Sassari (last but one Sunday in May), and the Redeemer in Nuoro (28 August). To this day Catalan is still spoken in the north-western city of Alghero (l'Alguer).

Many famines have been reported in Sardinia. According to Stephen L. Dyson and Robert J. Rowland, "The Jesuits of Cagliari recorded years during the late 16th century "of such hunger and so sterile that the majority of the people could sustain life only with wild ferns and other weeds" ... During the terrible famine of 1680, some 80,000 people, out of a total population of 250,000, are said to have died, and entire villages were devastated ... "[84]

Savoyard period

[edit]In 1708, as a consequence of the Spanish War of Succession, the rule of the Kingdom of Sardinia passed from King Philip V of Spain into the hands of the Austrians, who occupied the island. The Treaty of Utrecht granted Sardinia to the Austrians, but in 1717, Cardinal Giulio Alberoni, minister of Philip V of Spain, reoccupied Sardinia.

In 1718, with the Treaty of London, Sardinia was eventually handed over to the House of Savoy; this Alpine dynasty would go on to introduce the Italian language on the island forty years later in 1760, thereby starting a process of Italianization amongst the islanders.[85][86][87]

In 1793, Sardinians repelled the French Expédition de Sardaigne during the French Revolutionary Wars. On 23 February 1793, Domenico Millelire, commanding the Sardinian fleet, defeated the fleets of the French Republic near the Maddalena archipelago, of which then-lieutenant Napoleon Bonaparte was a leader.[88] Millelire became the first recipient of the Gold Medal of Military Valor of the Italian Armed Forces. In the same month, Sardinians stopped the attempted French landing on the beach of Quartu Sant'Elena, near the Capital of Cagliari. Because of these successes, the representatives of the nobility and clergy (Stamenti) formulated five requests addressed to the King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia, but they were all met with rejection. Because of this discontent, on 28 April 1794, during an uprising in Cagliari, two Savoyard officials were killed; that was the spark that ignited a revolt (called the "Sardinian Vespers") throughout the island, which started on 28 April 1794 (commemorated today as sa die de sa Sardigna) with the expulsion and execution of the Piedmontese officers for a few days from the Capital Cagliari.

On 28 December 1795 Sassari insurgents demonstrating against feudalism, mainly from the region of Logudoro, occupied the city. On 13 February 1796, in order to prevent the spread of the revolt, the viceroy Filippo Vivalda gave the Sardinian magistrate Giovanni Maria Angioy the role of Alternos, which meant a substitute of the viceroy himself. Angioy moved from Cagliari to Sassari, and during his journey almost all the villages joined the uprising, demanding an end to feudalism and aiming to declare the island to be an independent republic,[89][90] but once he was outnumbered by loyalist forces he fled to Paris and sought support for a French annexation of the island.

In 1798, the islet near Sardinia was attacked by the Tunisians and over 900 inhabitants were taken away as slaves.[91] The final Muslim attack on the island was on Sant'Antioco on 16 October 1815, over a millennium since the first.[92]

In 1799, as a consequence of the Napoleonic Wars in Italy, the Savoy royal family left Turin and took refuge in Cagliari for some fifteen years.[93] In 1847, the Sardinian parliaments (Stamenti), in order to get the Piedmontese liberal reforms they could not afford due to their separated legal system, renounced their state autonomy and agreed to form a union with the Italian Mainland States (Stati di Terraferma), ending up with a single parliament, a single magistracy and a single government in Turin; this move aggravated the island's peripheral condition[94] and most of the pro-union supporters, including its leader Giovanni Siotto Pintor, would later regret it.[95]

In 1820, the Savoyards imposed the Enclosures Act (Editto delle Chiudende) on the island, aimed at turning the land's traditional collective ownership, a cultural and economic cornerstone of Sardinia since the Nuragic times,[96] to private property. This gave rise to many abuses, as the reform ended up favouring the landholders while excluding the poor Sardinian farmers and shepherds, who witnessed the abolition of the communal rights and the sale of their lands. Many local rebellions like the Nuorese Su Connottu ('The Already Known' in Sardinian) riot in 1868,[97][98] all repressed by the King's army, resulted in an attempt to return to the past and reaffirm the right to use the once common land. However the common lands (called ademprivios) were never completely abolished, and they are still present in large number to this day (500,000 hectares of common lands were counted in 1956, of which 345,000 constituted by woods).[99]

Kingdom of Italy

[edit]With the Perfect fusion in 1848, the confederation of states powered by the Savoyard kings of Sardinia became a unitary and constitutional state and moved to the Italian Wars of Independence for the Unification of Italy, that were led for thirteen years. In 1861, being Italy united by a debated war campaign, the parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia decided by law to change its name and the title of its king to Kingdom of Italy and King of Italy. Most Sardinian forests were cut down at this time, in order to provide the Piedmontese with raw materials, like wood, used to make railway sleepers on the mainland. The primary natural forests, praised by every[citation needed] traveller visiting Sardinia, would in fact be reduced to one-fifth of their original number, being little more than 100,000 hectares at the end of the century.[100] From 1850 onward, taxes more than doubled in Sardinia, which compounded the already severe financial hardships facing the islanders, due to the Italo-French tariff war: between 1885 and 1897, the Sardinians saw their land being confiscated more than the rest of Italy combined as a result of tax evasion.[101]

During the First World War, the Sardinian soldiers of the Brigata Sassari distinguished themselves. It was the first and only regional military unit in Italy, since the people enrolled were only Sardinians. The brigade suffered heavy losses and earned four Gold Medals of Military Valor. Sardinia lost more young people than any other Italian region on the front, with 138 casualties per 1000 soldiers compared to the Italian average of 100 casualties.

During the Fascist period, with the implementation of the policy of autarky, several swamps around the island were reclaimed and agrarian communities founded. The main communities were the village of Mussolinia (now called Arborea), populated by farmers from Veneto and Friuli, in the area of Oristano and Fertilia, populated at first by settlers from the Ferrara area, followed, after World War II, by a notable number of Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians hailing from territories lost to Yugoslavia, in the area adjacent the city of Alghero, within the region of Nurra . Also established during that time (1938) was the city of Carbonia, which became the main centre of coal mining activity, that attracted thousand of workers from the rest of the Island and the Italian mainland. The Sardinian writer Grazia Deledda won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1926.

During the Second World War, Sardinia was an important air and naval base and was heavily bombed by the Allies, especially the city of Cagliari. German troops left the island on 8 September 1943, a few days after the Armistice of Cassibile, and retired to Corsica without fighting and bloodshed, after a bilateral agreement between the general Antonio Basso (Commander of the Armed Forces of Sardinia) and the German Karl Hans Lungerhausen, general of the 90th Panzergrenadier Division.[102]

Post-Second World War period

[edit]In 1946, by popular referendum, Italy became a republic, with Sardinia being administered since 1948 by a special statute of autonomy. By 1951, malaria was successfully eliminated by the ERLAAS, Anti-malaric Regional Authority, and the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, which facilitated the commencement of the Sardinian tourist boom.[103] With the increase in tourism, coal decreased in importance but Sardinia followed the Italian economic miracle.

In the early 1960s, an industrialisation effort was commenced, the so-called Piani di Rinascita (rebirth plans), with the initiation of major infrastructure projects on the island. These included the construction of new dams and roads, reforestation, agricultural zones on reclaimed marshland, and large industrial complexes (primarily oil refineries and related petrochemical operations). With the creation of petrochemical industries, thousands of ex-farmers became industrial workers. The 1973 oil crisis caused the termination of employment for thousands of workers employed in the petrochemical industries, which aggravated the emigration already present in the 1950s and 1960s.

Sardinia faced the creation of military bases on the island,[104][105] like Decimomannu Air Base and Salto di Quirra (the biggest scientific military base in Europe) in the same decades.[106] Even now, around 60% of all Italian and NATO military installations in Italy are on Sardinia, whose area is less than one-tenth of all the Italian territory and whose population is little more than the 2.5%;[107] furthermore, they comprise over 35,000 hectares used for experimental weapons testing,[108][109] where 80% of the military explosives in Italy are used.[110]

Sardinian nationalism and local protest movements became stronger in the 1970s, and a number of bandits (anonima sarda) started a long series of kidnappings, which ended only in the 1990s.[111] This also gave rise to various militant groups that blended separatist and communist ideas, the most famous being Barbagia Rossa and the Sardinian Armed Movement,[112] which perpetrated several bombings and terrorist actions between the 1970s and the 1980s.[113][114][115] In the span of just two years (1987–1988), 224 bombing attacks were reported.[116]

In 1983 a prominent activist of a separatist party, the Sardinian Action Party (Partidu Sardu – Partito Sardo d'Azione), was elected president of the regional parliament, and in the 1980s several other movements calling for independence from Italy were born; in the 1990s some of them became political parties, even if in a rather disjointed manner. It was not until 1999 that the island's languages (Sardinian, Sassarese, Gallurese, Algherese and Tabarchino) were recognised, even if just formally, together with Italian. The 35th G8 summit was planned by Prodi II Cabinet to be held in Sardinia, on the island of La Maddalena, in July 2009; however, in April 2009, the Italian Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi, decided, without convoking the Italian parliament or consulting the Sardinian governor of his own party, to move the summit, even though the works were almost completed, to L'Aquila, provoking heavy protests.

Today Sardinia is phasing in as an EU region, with a diversified economy focused on tourism and the tertiary sector. The economic efforts of the last twenty years have reduced the handicap of insularity, especially in the fields of low-cost air travel and advanced information technology. For example, the CRS4 (Center for Advanced Studies, Research and Development in Sardinia) developed the second European website and 1st in Italy in 1991[117] and webmail in 1995. CRS4 allowed several telecommunication companies and internet service providers based on the island to flourish, such as Videonline in 1994, Tiscali in 1998 and Andala Umts in 1999.

Environment

[edit]

Following an enormous reforestation plan Sardinia has become the Italian region with the largest forest extension. 1,213,250 hectares (12,132 km2) or 50% of the island is covered by forested areas.[118][119] The Corpo forestale e di vigilanza ambientale della Regione Sarda is the Sardinian Forestry Corps. Sardinia is one of the regions in Italy which are most affected by forest fires during the summer.[120]

The Regional Landscape Plan prohibits new building activities on the coast (except in urban centers), next to forests, lakes or other environmental or cultural sites and the Coastal conservation agency ensures the protection of natural areas on the Sardinian coast.

Renewable energies have increased noticeably in recent years,[121] mainly wind power, favoured by the windy climate, but also solar power and biofuel, based on jatropha oil and colza oil. 586.8 megawatts of wind power capacity were installed on the island at the end of 2009.[122]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Due to Sardinia's continual isolation from mainland Europe even during glacial sea level lows (when it was connected to Corsica), Sardinia has a high level of endemism, with regards to both flora[124] and fauna, including insects[125] and arachnids,[126] as well as terrestrial vertebrates, with endemic amphibians (including those also found on Corsica) including the Sardinian brook salamander, brown cave salamander, imperial cave salamander, Monte Albo cave salamander, Supramonte cave salamander, Sarrabus cave salamander (Speleomantes sarrabusensis) and Sardinian tree frog (also found in Corsica), with lizards endemic to the archipelago including Bedriaga's rock lizard, Tyrrhenian wall lizard and Fitzinger's algyroides.

During the Late Pleistocene, Sardinia and Corsica had a highly endemic terrestrial mammal fauna, all of which is now extinct, which included a field mouse (Rhagamys orthodon), a vole (Microtus henseli), a shrew (Asoriculus similis), a mole (Talpa tyrrhenica), a dwarf mammoth (Mammuthus lamarmorai), the Sardinian pika (Prolagus sardus), a jackal-sized canine, the Sardinian dhole (Cynotherium sardus), a mustelid (Enhydrictis galictoides), three species of otter (Algarolutra majori, Sardolutra ichnusae, and the gigantic Megalenhydris barbaricina) and a deer (Praemegaceros cazioti).[127] Some of these animals were extinct by the beginning of the Holocene, with the deer species suggested to have persisted until around 7,600 years ago,[128] and the shrew into the Neolithic, while the Sardinian pika, vole and field mouse are suggested to have persisted until around 3000–2000 years ago.[129] The Sardinian pika in particular was historically abundant on the island, and was used by early inhabitants as a source of food.[130] On the present-day island, its fauna includes a variety of introduced mammal species, such as the Corsican red deer.

The island is inhabited by terrestrial tortoises and sea turtles like Hermann's tortoise, the spur-thighed tortoise, marginated tortoise (Testudo marginata sarda), Nabeul tortoise, loggerhead sea turtle and green sea turtle.

Some birds of prey found here are the griffon vulture, common buzzard, golden eagle, long-eared owl, western marsh harrier, peregrine falcon, European honey buzzard, Sardinian goshawk (Accipiter gentilis arrigonii), Bonelli's eagle and Eleonora's falcon, whose name comes from Eleonor of Arborea, national heroine of Sardinia, expert in falconry.[131] The hundreds of lagoons and coastal lakes that dot the island are home for many species of wading birds, such as the greater flamingo.

Conversely, Sardinia lacks many species common on the European continent, such as the viper, wolf, bear and marmot.

The island has also long been used for grazing flocks of indigenous Sardinian sheep. The Sardinian Anglo-Arab is a horse breed that was established in Sardinia, where it has been selectively bred for more than one hundred years.

Three different breeds of dogs are peculiar to Sardinia: the Sardinian Shepherd Dog, the Dogo Sardesco and the Levriero Sardo.

Natural parks and reserves

[edit]

Over 600,000 hectares (1,500,000 acres) of Sardinian territory is environmentally preserved[132][133] (about 25% of the island's territory). The island has three national parks:[134]

- 1. Asinara National Park,

- 2. Arcipelago di La Maddalena National Park, and

- 3. Gennargentu National Park.

- The numbers correspond to those in the map to right.

Ten regional parks:

- 4. Parco del Limbara

- 5. Parco del Marghine e Goceano

- 6. Parco del Sinis – Montiferru

- 7. Parco di Monte Arci

- 8. Parco della Giara di Gesturi

- 9. Parco di Monte Linas – Oridda – Marganai

- 10. Parco dei Sette Fratelli – Monte Genas

- 11. Parco del Sulcis

- Parco naturale regionale di Porto Conte

- Parco regionale Molentargius – Saline

There are 60 wildlife reserves, 5 W.W.F oases, 25 natural monuments and one Geomineral Park, preserved by UNESCO.[135]

Northern Sardinian Coasts are included in the Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean Marine Mammals, a Marine Protected Area, that covers a surface of about 84,000 km2 (32,433 sq mi), aimed at the protection of marine mammals.

Education

[edit]

According to the ISTAT census of 2001, the literacy rate in Sardinia among people below 65 years old is 99.5 percent. Total literacy rate (including people over 65) is 98.2 percent.[136][137] The illiteracy rate among males below 65 years old is 0.24 percent and among women 0.25 percent;[136] the number of women that annually graduate at secondary high schools and universities is about 10–20 percent higher than men.[137][138] Sardinia has the 2nd highest rate of school drop-out in Italy.[139]

Sardinia has two public universities: the University of Sassari and the University of Cagliari, founded in the 16th and 17th century. 48,979 students were enrolled at universities in 2007–2008.[140]

Economy

[edit]

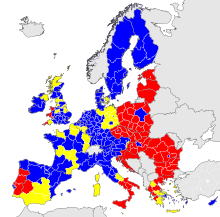

Of the Italian regions located south of Rome, Sardinia's economy is in the best state. The greatest amount of economic development took place inland, in the provinces of Cagliari and Sassari, characterized by a certain amount of enterprise. According to Eurostat, the 2014 nominal gross domestic product (GDP) was €33,356 million, €33,085 million in purchasing power parity, resulting in a GDP per capita of €19,900, which is 72% of the EU average. The per capita income in Sardinia is the highest of the southern half of Italy. The most populated provincial chief towns have higher incomes: in Cagliari the income per capita is €27,545, in Sassari €24,006, in Oristano €23,887, in Nuoro is €23,316 and in Olbia is €20,827.[141] Sardinia is the 14th most productive region in the country and is the 16th for GRP per capita among Italian regions.[142]

The Sardinian economy is, however, constrained due to the high costs of the transportation of goods and electricity, which is twice that of the continental Italian regions, and triple that of the EU average. Sardinia is the only Italian region that produces a surplus of electricity, and exports electricity to Corsica and the Italian mainland: in 2009, the new submarine power cable Sapei entered into operation. It links the Fiume Santo Power Station, in Sardinia, to the converter stations in Latina, in the Italian peninsula. The SACOI is another submarine power cable that links Sardinia to Italy, crossing Corsica, from 1965.

Small scale liquified natural gas terminals and a 404 km (251 mi) gas pipeline were under construction, and became operational in 2018. They will decrease the current high cost of the electric power in the island.[143][144] As of 2021[update], Sardinia has 2 GigaWatts (GW) of thermal power plants, 1 GW each of wind and solar power, and over 450 MW of hydropower.[145]

Three main banks are headquartered in Sardinia; however, Banco di Sardegna and Banca di Sassari, are both originally from Sassari.

There are chances for Sardinia to become a tax haven as the whole island territory is free of custom duties, value added tax (VAT) and excise taxes on fuel; since February 2013, the town of Portoscuso has become the first free trade zone.[146][147][148][149][150] According to the article 12 of the Sardinian Statute modified by the regional parliament in October 2013: "The Territory of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia is located off the customs line and constitutes a Free Trade Zone enclosed by the surrounding sea; the access points consist of the seaports and the airports. The Sardinian Free Trade Zone is regulated by the laws of the European Union and Italy that are in force also in Livigno, Campione D'Italia, Gorizia, Savogna d'Isonzo and the Region of Aosta Valley".

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product nominal (Million €) |

25,958.1 | 27,547.6 | 28,151.6 | 29,487.3 | 30,595.5 | 31,421.3 | 32,579.0 | 33,823.2 |

| GDP per capita nominal (Euro) |

15,861.0 | 16,871.4 | 17,226.5 | 17,975.7 | 18,581.0 | 19,009.8 | 19,654.3 | 20,444.1 |

Unemployment

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (September 2024) |

The unemployment rate for the fourth quarter of 2008 was 8.6%; by 2012, the unemployment rate had increased to 14.6%.[151] Its rise was due to the Great Recession that reduced Sardinian exports, mainly focused on refined oil, chemical products, and also mining and metallurgical products.

The unemployment rate dropped to 11.2% at the end of 2018, which is only 1.8 percentage points (pp) higher than the national average (9.4%) and 5.3pp lower than Southern Italian regions (16.5%), according to Italian National Institute of Statistics.[152][153][154][155][156]

Economic sectors

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (September 2024) |

This table shows the sectors of the Sardinian economy in 2011:[157]

| Economic activity | GDP (mil. €) | % sector |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, farming, fishing | 908 | 3% |

| Industry | 2,828 | 9.4% |

| Constructions | 1,722 | 5.7% |

| Commerce, hotels and restaurants, transport, services and (tele)communications | 7,597 | 25.4% |

| Financial activity and real estate | 8,011 | 26.7% |

| Other economic activities related to services | 8,896 | 29.7% |

| Total value added | 29,962 | 100% |

| GDP of Sardinia | 33,638 |

Primary

[edit]

Sardinia is home to nearly four million sheep,[158] almost half of the entire Italian assets and that makes the island one of the areas of the world with the highest density of sheep along with some parts of the United Kingdom and New Zealand (135 sheep every square kilometer versus 129 in UK and 116 in New Zealand). Sardinia has been for thousands of years specializing in sheep breeding, and, to a lesser extent, goats and cattle that is less productive of agriculture in relation to land use. It is probably in breeding and cattle ownership the economic base of the early proto-historic and monumental Sardinian civilization from Neolithic to the Iron Age.

Agriculture has also played a very important role in the economic history of the island, especially in the great plain of Campidano, particularly suitable for wheat farming. Sardinian soil often has insufficient or brackish water aquifers, even on its more permeable plains. As such, water scarcity was the first problem that was faced for the modernization of the sector, with the construction of a great barrier system of dams, which today contains nearly 2 billion cubic meters of water.[159] The Sardinian agriculture is now linked to specific products such as cheese, wine, olive oil, artichoke, tomato for a growing product export. The reclamations have helped to extend the crops and to introduce other ones such as vegetables and fruit, next to the historical ones, olive and grapes that are present in the hilly areas. The Campidano plain, the largest lowland Sardinian produces oats, barley and durum, of which is one of the most important Italian producers. Among the vegetables, as well as artichokes, has a certain weight the production of oranges, and, before the reform of the sugar sector from the European Union, the cultivation of sugar beet.

In the forests there is the cork oak, which grows naturally; Sardinia produces about 80% of Italian cork. The cork district, in the northern part of the Gallura region, around Calangianus and Tempio Pausania, is composed of 130 companies. Every year in Sardinia 200,000 quintals (20,000 tonnes) of cork are carved, and 40% of the end products are exported.

In fresh food, as well as artichokes, the production of tomatoes (including Camoni tomato) and citrus fruit are of a certain weight. Sardinia is the 5th Italian region for rice production, the main paddy fields are located in the Arborea Plain.[160]

In addition to meat, Sardinia produces a wide variety of cheese, considering that half of the sheep milk produced in Italy is produced in Sardinia, and is largely worked by the cooperatives of the shepherds and small industries.[161] Sardinia also produces most of the pecorino romano, a non-original product of the island, much of which is traditionally addressed to the Italian overseas communities. Sardinia boasts a centuries-old tradition of horse breeding since the Aragonese domination, whose cavalry drew from equine heritage of the island to strengthen their own army or to make a gift to the other sovereigns of Europe.[162] Today the island boasts the highest number of horse herds in Italy.[163]

There is little fishing (and no real maritime tradition), Portoscuso tunas are exported worldwide, but primarily to Japan.

Industry and handicraft

[edit]

The once prosperous mining industry is still active though restricted to coal (Nuraxi Figus, hamlet of Gonnesa),[164] antimony (Villasalto), gold (Furtei), bauxite (Olmedo) and lead and zinc (Iglesiente, Nurra). The granite extraction represents one of the most flourishing industries in the northern part of the island. The Gallura granite district is composed of 260 companies that work in 60 quarries, where 75% of the Italian granite is extracted. The principal industries are chemicals (Porto Torres, Cagliari, Villacidro, Ottana), petrochemicals (Porto Torres, Sarroch), metalworking (Portoscuso, Portovesme, Villacidro), cement (Cagliari), pharmaceutical (Sassari), shipbuilding (Arbatax, Olbia, Porto Torres), oil rig construction (Arbatax), rail industry (Villacidro),[165][166] arms industries at Domusnovas[167][168] and food (sugar refineries at Villasor and Oristano, dairy at Arborea, Macomer and Thiesi, fish factory at Olbia).

In Sardinia is located the DASS (Distretto Aerospaziale della Sardegna), a consortium of companies, research centers and universities focused on aerospace industry and research.[169][170][171] The aerospace manufacturer Vitrociset, in Villaputzu, is involved in the production of the stealth multirole fighter Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II.[172][173]

Plans related to industrial conversion are in progress in the main industrial sites, like in Porto Torres, where seven research centres are developing the transformation from traditional fossil fuel related industry to an integrated production chain from vegetable oil using oleaginous seeds to bio-plastics.[174][175]

Sardinia is involved in the industrial production of the AIRPod, an innovative car powered by compressed air, with the first factory being built in Bolotana.[176][177][178][179]

Craft industries include rugs, jewelry, textile, lacework, basket making and coral.

Tertiary

[edit]

The Sardinian economy is today focused on the overdeveloped tertiary sector (67.8% of employment), with commerce, services, information technology, public administration and especially on tourism (mainly seaside tourism), which represents the main industry of the island with 2,721 active companies and 189,239 rooms. In 2008 there were 2,363,496 arrivals (up 1.4% on 2007). In the same year, the airports of the island registered 11,896,674 passengers (up 1.24% on 2007).[180]

Due to its isolated and insular location, Sardinia focused part of its economy on the development of digital technologies since the dawn of internet era: the first Italian website, one of the first webmail system and one of the first and largest internet providers (Video On Line) were realised by the CRS4,[181][182] the first European online newspaper was developed by L'Unione Sarda[183][184] and also the first Italian UMTS company was founded on the island. Today Sardinia is the second Italian region, after Lombardy, for investments in startups (owning the 20% of the Italian venture capital).[185][186]

Sardinia has many small and picturesque villages, nine of them have been selected by I Borghi più belli d'Italia (English: The most beautiful Villages of Italy),[187] a non-profit private association of small Italian towns of strong historical and artistic interest,[188] that was founded on the initiative of the Tourism Council of the National Association of Italian Municipalities.[189]

Communications

[edit]

On the island are headquartered some telecommunication companies and internet service providers, such as Tiscali and the Mediterranean Skylogic Teleport, a ground station controlled by satellite provider Eutelsat.[190] Sardinia is the Italian region with the highest e-intensity index after the Aosta Valley[191][192] (index measuring the relative maturity of Internet economies on the basis of three factors: enablement, engagement, and expenditure) and the region with the highest internet performances, such as fastest broadband connection in Italy.[193] Sardinia is also the Italian region with the highest percentage (41%) of 4G LTE users.[194] The Chinese multinational telecommunications equipment and systems companies ZTE and Huawei have development centers and innovation labs in Sardinia.[195]

Sardinia has become Europe's first region to fully adopt the new Digital Terrestrial Television broadcasting standard. From 1 November 2008 TV channels are broadcast only in digital.[196]

Transport

[edit]Airports

[edit]Sardinia has three international airports (Alghero-Fertilia/Riviera del Corallo Airport, Olbia-Costa Smeralda Airport and Cagliari-Elmas Airport) connected with the principal Italian cities and many European destinations, mainly in the United Kingdom, France, Spain and Germany, and two regional airports (Oristano-Fenosu Airport and Tortolì-Arbatax Airport). Internal air connections between Sardinian airports are limited to a daily Cagliari-Olbia flight. Sardinian citizens benefit from special sales on plane tickets for Rome and Milan (continuità territoriale),[197] and several low-cost air companies operate on the island.

Air Italy (formerly known as Meridiana) was an airline headquartered in the airport of Olbia; it was founded as Alisarda in 1963 by the Aga Khan IV. The development of Alisarda followed the development of Costa Smeralda in the northeast part of the island, a well known vacation spot among billionaires and film actors worldwide.

Seaports

[edit]

The ferry companies operating on the island are Tirrenia di Navigazione, Moby Lines, Corsica Ferries - Sardinia Ferries, Grandi Navi Veloci, Grimaldi Lines, Corsica Linea; they link the Sardinian seaports of Porto Torres, Olbia, Golfo Aranci, Arbatax, Santa Teresa Gallura and Cagliari with Civitavecchia, Genoa, Livorno, Naples, Palermo, Trapani, Piombino in Italy, Marseille, Toulon, Bonifacio, Propriano and Ajaccio in France and Barcelona in Spain.

Caronte & Tourist and Delcomar links the main island to the islands of La Maddalena and San Pietro.

About 40 tourist harbours are located along the Sardinian coasts.

Roads

[edit]

Sardinia is the only Italian region without Autostrade (en:motorways), but the road network is well developed with a system of no-toll roads with dual carriageway, called superstrade ('super roads') that connect the principal towns and the main airports and seaports; the speed limit is 90 km/h (56 mph)/110 km/h (68 mph). The principal road is the SS131 "Carlo Felice", linking the south with the north of the island, crossing the most historic regions of Porto Torres and Cagliari; it is part of European route E25. The SS 131 d.c.n links Oristano with Olbia, crossing the hinterland Nuoro region. Other roads designed for high-capacity traffic link Sassari with Alghero, Sassari with Tempio Pausania, Sassari – Olbia, Cagliari – Tortolì, Cagliari – Iglesias, Nuoro – Lanusei. A work in progress is converting the main routes to highway standards, with the elimination of all intersections. The secondary inland and mountain roads are generally narrow with many hairpin turns, so the speed limits are very low.

Public transport buses reach every town and village at least once a day; however, due to the low density of population, the smallest territories are reachable only by car. The Azienda Regionale Sarda Trasporti (ARST) is the public regional bus transport agency. Networks of city buses serve the main towns (Cagliari, Iglesias, Oristano, Alghero, Sassari, Nuoro, Carbonia and Olbia).

In Sardinia 1,295,462 vehicles circulate, equal to 613 per 1,000 inhabitants.[198]

Railways

[edit]

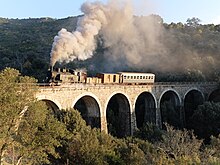

The Sardinian railway system was developed starting from the 19th century by the Welsh engineer Benjamin Piercy.

Today there are two different railway operators:

- Trenitalia which connects the most populated towns and the main ports. This network is the most modern on the island, running primarily diesel locomotives such as the Alstom Minuetto and, from 2015 the faster tilting train CAF ATR365 and ATR 465, specifically designed for the Sardinian railway network;[199]

- ARST: the trains run on narrow-gauge track, are generally slow, due to the tortuosity of the lines, except for the electrified tram-trains operating in the metropolitan areas of Sassari and Cagliari.

The Trenino Verde (Little Green Train) is a railway tourism service operated by ARST. Vintage railcars and steam locomotives run through the wildest parts of the island. They allow the traveller to have scenic views impossible to see from the main roads.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1485 | 157,578 | — |

| 1603 | 266,676 | +69.2% |

| 1678 | 299,356 | +12.3% |

| 1688 | 229,532 | −23.3% |

| 1698 | 259,157 | +12.9% |

| 1728 | 311,902 | +20.4% |

| 1751 | 360,805 | +15.7% |

| 1771 | 360,785 | −0.0% |

| 1776 | 422,647 | +17.1% |

| 1781 | 431,897 | +2.2% |

| 1821 | 461,931 | +7.0% |

| 1824 | 469,831 | +1.7% |

| 1838 | 525,485 | +11.8% |

| 1844 | 544,253 | +3.6% |

| 1848 | 554,717 | +1.9% |

| 1857 | 573,243 | +3.3% |

| 1861 | 609,000 | +6.2% |

| 1871 | 636,000 | +4.4% |

| 1881 | 680,000 | +6.9% |

| 1901 | 796,000 | +17.1% |

| 1911 | 868,000 | +9.0% |

| 1921 | 885,000 | +2.0% |

| 1931 | 984,000 | +11.2% |

| 1936 | 1,034,000 | +5.1% |

| 1951 | 1,276,023 | +23.4% |

| 1961 | 1,419,362 | +11.2% |

| 1971 | 1,473,800 | +3.8% |

| 1981 | 1,594,175 | +8.2% |

| 1991 | 1,648,248 | +3.4% |

| 2001 | 1,631,880 | −1.0% |

| 2011 | 1,639,362 | +0.5% |

| 2021 | 1,587,413 | −3.2% |

| Source: ISTAT, – D.Angioni-S.Loi-G.Puggioni, La popolazione dei comuni sardi dal 1688 al 1991, CUEC, Cagliari, 1997 – F. Corridore, Storia documentata della popolazione di Sardegna, Carlo Clausen, Torino, 1902 | ||

With a population density of 69/km2, slightly more than a third of the national average, Sardinia is the fourth-least populated region in Italy. In the recent past the population distribution was anomalous compared to that of other Italian regions lying on the sea. In fact, contrary to the general trend, most urban settlement, with the exception of the fortified cities of Cagliari, Alghero, Castelsardo and few others, has taken place not primarily along the coast but in the subcoastal areas and towards the centre of the island. Historical reasons for this include the repeated Saracen raids during the Middle Ages and then Barbary raids until the early 19th century (making the coast unsafe), widespread pastoral activities inland, and the swampy nature of the coastal plains (reclaimed definitively only in the 20th century). The situation has been reversed with the expansion of seaside tourism; all of Sardinia's major urban centres are now located near the coasts, and the island's interior is very sparsely populated.

It is the region with the lowest total fertility rate[200] (1.087 births per woman) and the second-lowest birth rate of Italy[201] (which is already one of the lowest in the world). Combined with the aging of population going rather fast (in 2009, people older than 65 were 18.7%), rural depopulation is quite a big issue: between 1991 and 2001, 71.4% of Sardinian villages have lost population (32 more than 20% and 115 between 10% and 20%), with over 30 of them being at risk to become ghost towns.[202] It is predicted that at that rate, Sardinia will be the European island with the second-lowest population density, immediately after Iceland, by 2080.[203][204]

Nonetheless, the overall population estimate has remained relatively stable because of a considerable immigration flow, mainly from the Italian mainland, but also from Eastern Europe (especially Romania), Africa and Asia.

Life expectancy

[edit]Average life expectancy is slightly over 82 years (85 for women and 79.7 for men[205]). Sardinia shares with the Japanese island of Okinawa the highest rate of centenarians in the world (22 centenarians per 100,000 inhabitants). Sardinia is the first discovered Blue Zone, a demographic or geographic area in the world with an oversize concentration of centenarians and supercentenarians.

Foreign immigration

[edit]In 2023, there were 50,211 foreign national residents, forming 3,2% of the total Sardinian population.[206] The most represented nationalities were:[206]

Romania 11,313

Romania 11,313 Senegal 4,289

Senegal 4,289 Morocco 3,982

Morocco 3,982 China 3,253

China 3,253 Ukraine 2,885

Ukraine 2,885 Philippines 1,969

Philippines 1,969 Nigeria 1,795

Nigeria 1,795 Bangladesh 1,406

Bangladesh 1,406 Germany 1,214

Germany 1,214 Pakistan 1,047

Pakistan 1,047 Poland 1,037

Poland 1,037 Kyrgyzstan 946

Kyrgyzstan 946 Russia 788

Russia 788 France 763

France 763 Albania 762

Albania 762 United Kingdom 710

United Kingdom 710

Main cities and Functional Urban Areas

[edit]

Sardinia's most populated cities are Cagliari and Sassari. The Metropolitan City of Cagliari has 431,302 inhabitants, or about ¼ of the population of the entire island. Eurostat has identified in Sardinia two Functional Urban Areas:[207] Cagliari, with 477,000 inhabitants, and Sassari, with 222,000 inhabitants.

| Rank | Commune | Province | Population[208] | Density (inh./km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Cagliari / Casteddu (Sardinian) | Metropolitan City of Cagliari | 154,460 | 1,805 |

| 2nd | Sassari / Sassari (Sassarese) / Tatari (Sardinian) | Province of Sassari | 127,525 | 230 |

| 3rd | Quartu Sant'Elena / Cuartu Sant'Aleni[209] (Sardinian) | Metropolitan City of Cagliari | 71,125 | 719 |

| 4th | Olbia / Terranoa (Sardinian) / Tarranoa (Gallurese) | Province of Sassari | 59,368 | 146 |

| 5th | Alghero / L'Alguer (Catalan) | Province of Sassari | 44,019 | 181 |

| 6th | Nuoro / Nùgoro (Sardinian) | Province of Nuoro | 37,091 | 189 |

| 7th | Oristano / Aristanis (Sardinian) | Province of Oristano | 31,630 | 380 |

| 8th | Carbonia / Crabònia (Sardinian) | Province of South Sardinia | 28,755 | 197 |

| 9th | Selargius / Ceraxius[209] (Sardinian) | Metropolitan City of Cagliari | 28,975 | 1092 |

| 10th | Iglesias / Igrèsias or Bidd'e Cresia (Sardinian) | Province of South Sardinia | 27,189 | 133 |

| 11th | Assemini / Assèmini[209] (Sardinian) | Metropolitan City of Cagliari | 26,686 | 238 |

| 12th | Capoterra / Cabuderra[209] (Sardinian) | Metropolitan City of Cagliari | 23,861 | 349 |

| 13th | Porto Torres / Posthudorra (Sassarese) | Province of Sassari | 22,313 | 218 |

| 14th | Sestu[209] (Sardinian) | Metropolitan City of Cagliari | 20,454 | 423 |

| 15th | Monserrato / Pauli[209] (Sardinian) | Metropolitan City of Cagliari | 20,055 | 3,180 |

Government and politics

[edit]Sardinia is one of the five Italian autonomous regions, along with the Aosta Valley, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Sicily. Its particular statute, which in itself is a constitutional law, gives the region a limited degree of autonomy, entailing the right to carry out the administrative functions of the local body and to create its own laws in a strictly defined number of domains.

The regional administration is constituted by three authorities:

- the Regional Council (legislative power)

- the Regional Junta (executive power)

- the President (chief of executive power)

Administrative divisions

[edit]Since 2016, Sardinia is divided into four provinces[210] (Nuoro, Oristano, Sassari, South Sardinia) and the metropolitan city of Cagliari.

| Province | Area (km2) | Population | Density (inh./km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cagliari (metropolitan city) | 1,248 | 431,568 | 345.8 |

| Province of Nuoro | 5,786 | 213,206 | 36.8 |

| Province of Oristano | 3,034 | 160,864 | 53.0 |

| Province of Sassari | 7,692 | 494,388 | 64.2 |

| Province of South Sardinia | 6,339 | 358,229 | 56.5 |

Military installations

[edit]

Around 60% of all the military installations in Italy are in Sardinia, whose area is less than one-tenth of all the Italian territory and whose population is little more than the 2,5%.[211] The island hosts NATO joint forces and Israeli military forces, which use the island's territory to simulate war games; the Inter-service Test and Training Range of Salto di Quirra (PISQ) is one of the most important experimental military training centres in Europe.[212] The bases, used for manufacturing plants and military testing grounds, totally take up more than 350 km2 of the island's land,[213] making Sardinia the most militarized region in Italy and the most militarized island in Europe.[214][215][216]

Besides the land-occupying installations, where 80% of the military explosives in Italy are used,[110] there are also other military structures located on the sea and along the coastline, roughly equivalent to 20000 km2 (little less than the island's surface), being made inaccessible to the civil population when military exercises are held.[213][216]

Among the most notable military bases on the island are the Interagency Polygons in Quirra, Capo Teulada and Capo Frasca, used by Italian and NATO forces to test-fire ballistic missiles and weapons and by Italian and European Space Agency to test space vehicles and for orbital launches. Until 2008, the US navy also had a nuclear submarine base in the Maddalena Archipelago.[213][105]