Giants of Mont'e Prama

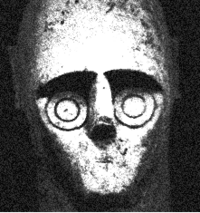

Giant head from Mont'e Prama | |

| Location | Cabras, Province of Oristano |

|---|---|

| Region | Sinis peninsula, Sardinia, Italy |

| Coordinates | 39°57′57″N 8°26′54″E / 39.965778°N 8.448278°E |

| Type | Sculptures |

| Part of | Heroon, Giants' grave, Necropolis (debated) |

| Area | ≈ 75000 m2 |

| Height | 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) |

| History | |

| Builder | Nuragic Sardinians |

| Material | limestone |

| Founded | Between the 11th and the 8th century BC (debated) |

| Abandoned | Late 4th century BC – first decades of the 3rd century BC |

| Periods | Iron Age I |

| Cultures | Nuragic civilisation |

| Associated with | Nuragic aristocrats |

| Events | Sardo–punic wars (debated) |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1974: G. Atzori; 1975: A. Bedini; 1977: G. Lilliu, G. Tore, E. Atzeni; 1977: G. Pau, M. Ferrarese Ceruti – C. Tronchetti |

| Condition | Sculptures restored at the Centro di restauro e conservazione dei beni culturali of Li Punti (Sassari) — Necropolis not yet fully excavated |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | monteprama.it |

The Giants of Mont'e Prama (Italian: Giganti di Mont'e Prama; Sardinian: Zigantes de Mont'e Prama[1] [dziˈɣantɛz dɛ ˈmɔntɛ ˈβɾama]) are ancient stone sculptures created by the Nuragic civilization of Sardinia, Italy. Fragmented into numerous pieces, they were discovered in March 1974 on farmland near Mont'e Prama, in the comune of Cabras, province of Oristano, in central-western Sardinia. The statues are carved in local sandstone and their height varies between 2 and 2.5 meters.[2]

After four excavation campaigns carried out between 1975 and 1979, the roughly five thousand pieces recovered – including fifteen heads and twenty two torsos – were stored for thirty years in the repositories of the National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari, while a few of the most important pieces were exhibited in the museum itself.[3] Along with the statues, other sculptures recovered at the site include large models of nuraghe buildings and several baetyl sacred stones of the "oragiana" type, used by Nuragic Sardinians in the making of "giants' graves".[a]

After the funds allocation of 2005 by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and the Sardinia Region, restoration was being carried out from 2007 until 2012 at the Centro di restauro e conservazione dei beni culturali of "Li Punti" (Sassari), coordinated by the Soprintendenza of cultural heritage for Sassari and Nuoro, together with the Soprintendenza of Cagliari and Oristano. At this location, twenty five statues, consisting of warriors, archers, boxers, and nuraghe models, have been exhibited to the public at special events since 2009.[4] The exhibition has become permanently accessible to the public since November 2011.

According to the most recent estimates, the fragments came from a total of forty-four statues. Twenty-five have already been restored and assembled in addition to thirteen nuraghe models, while another three statues and three nuraghe models have been identified from fragments that cannot currently be reconstructed. Once the restoration has been completed, it is planned to return the majority of the finds to Cabras to be displayed in a museum.[4][5]

Depending on the different hypotheses, the dating of the Kolossoi – the name that archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu gave to the statues[6] – varies between the 11th and the 8th century BC.[7] If this is further confirmed by archaeologists, they would be the most ancient anthropomorphic sculptures of the Mediterranean area, after the Egyptian statues, preceding the kouroi of ancient Greece.[8]

The scholar David Ridgway on this unexpected archaeological discovery wrote:

... during the period under review (1974–1979), the Nuragic scene has been enlivened by one of the most remarkable discoveries made anywhere on Italian soil in the present century (20th century)...

— David Ridgway, Archaeology in Sardinia and Etruria, 1974 – 1979. Archaeological Reports, 26 (1979–1980), pp 54–70,[9]

while the archaeologist Miriam Scharf Balmuth said:

...a stunning archaeological development, perhaps the most extraordinary find of the century in the realm of art history ...

— Joseph J. Basile, The Capestrano Warrior and Related Monuments of the Seventh to Fifth Centuries B.C, p 22.[10]

History of Prenuragic statuary

[edit]Venus figures

[edit]

The first attestations of sculpture in Sardinia are much more ancient than the statues of Mont'e Prama. The oldest example is the figurine that is referred to as, the Venus of Macomer,[12] in non finito technique, dated to 3750–3300 BC by the archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, however, the archaeologist Enrico Atzeni has suggested that the statuette likely dates back to Early Neolithic (6000–4000 BC).[13] More recent studies have stressed the similarities to the Venus figurines, already noticed by Giovanni Lilliu, and hypothesized a retro-dating to Upper Palaeolithic or Mesolithic Age.[14][15]

Statuettes later than this one – but still pertaining to the Mother Goddess iconography – are many volumetric figurines produced by the Ozieri culture, among which is the idol of Perfugas, representing a goddess suckling her child. The same symbolism was later used by the Nuragic civilization with the so-called "Nuragic pietà".[16][17]

After the three-dimensional figurines of the goddess – but still belonging to the Neolithic Age – are the idols in flat geometric style, that could represent the goddess in her chthonic aspect, in that all examples of this type of idol have been found inside graves.[18]

Investigations carried out after the fortuitous discovery of a prehistoric altar at Monte d'Accoddi (Sassari), have revealed that – alongside the production of geometric figurines – the great statuary was already present at that time in Sardinia, given that at the "temple of Accoddi" several stelae and menhirs were recovered. Beside the ramp leading to the top of the main building, excavations revealed the presence of a great menhir, with several others positioned around it. A sculpted face, engraved with spiraliform patterns and probably belonging to a statue-stele, has been assigned to the earliest phase of the site – called the "red-temple". A large granite stele with a female figure in relief, has been attributed to the second phase – called the "great-temple".[19]

Still in the time-frame of the Prenuragic age, but in this case during the Eneolithic period, there is a remarkable production of "Laconi-type" statue-menhirs or statue-stelae, assigned to the Abealzu-Filigosa culture and characterized by a uniform tripartite scheme encompassing, from top to bottom: a stylized T-shaped human face; the depiction of the enigmatic capovolto (the capsized) in the kind of trident capovolto; and a double-headed dagger in relief.[11][20]

After the spreading of Bonnanaro culture on the island, the tradition of the statue-stelae seems to die out, while it continues until 1200 BC with the Nuragic-related Torrean civilization facies of Corsica, featuring warriors represented in the Filitosa sculptures.

Warrior figures

[edit]

From aniconic baetyls to Nuragic statuary

[edit]During the Early Bronze Age the "epicampaniform style", a late expression of the Bell-Beaker culture, became spread both in Sardinia and Corsica. From this cultural period the Nuragic civilization would arise, paralleling similar architectural developments in southern Corsica, in such a way that the Gallura Nuragic facies shows a synchronic evolution with the Nuragic torrean civilization.[21][22][23]

However, while common architectonic traditions of Central-Western Mediterranean evidence the close relationships between islands, it is exactly the sculpture tradition that begins to diversify. In fact, while Early Bronze Age Sardinia abandoned the traditions of Eneolithic statue-stelae, in Corsica the production of menhirs continued without interruption, eventually originating the Torrean statue-stelae during the Middle and Late Bronze Age.[24]

An intermediate stage of this process could be represented by the appearance of hammered relief sculptures during the Middle Bronze Age – in both Sardinia and Corsica: in the former country, baetyls were engraved with male or female gender characters in relief, while in the latter – perhaps due to the greater presence of metal implements – relief sculpture was applied for the first time to menhirs. In both islands, anthropomorphic statuary in the strict sense of the word would not exist between 1600 and 1250 BC, but gender characteristics and weapons were represented in Sardinia and Corsica respectively.[23] In a successive evolution stage, the relief technique was employed in Sardinia – for the first time after Eneolithic sculptures – to represent a human face, as shown in the famous baetyl of "San Pietro di Golgo" (Baunei).[25][26][27]

There is no longer any dispute about the authenticity and Nuragic manufacture of the three statue-baetyls discovered in northern Sardinia, a region where a Corsican population of Nuragic culture was probably settled. At first the three statues were considered to be Punic or Roman artefacts,[28] but these sculptures evidently portray warriors with an envelope-shaped, crested and horned nuragic helmet – as also suggested by the crest and by the circular cavities that probably held the horns (these latter still present in the statue-baetyl from Bulzi, Sassari).[29][30]

According to the archaeologist Fulvia Lo Schiavo, the sculptures of northern Sardinia testify the existence of a Nuragic proto-statuary, an intermediate step of an evolutionary process that from the "eyed baetyls" of the "Oragiana type", would eventually lead to the anthropomorphic statues of Mont'e Prama. This hypothesis agrees with an earlier idea carried out by Giovanni Lilliu, following the examination of the "baetylus of Baunei",[29][31] where the famous archaeologist saw the abandonment of the ancient aniconic ideology and a revival of the human form representation:

This process is somehow revealed by the transition from a representation of the human via sketched face or body features (like in the cone-shaped baetyl of "Tamuli" and "San Costantino di Sedilo", and in the truncated conical baetyl of "Nurachi", "Solene", "Oragiana"), to a full and pronounced human head representation in the "baetylus of Baunei". This leads to suppose that the "baetylus of Baunei" is the arrival point of an ideological and artistic evolution, in a pathway ascending from symbolism to anthropomorphism, due to various factors inside and outside Sardinia.

— Giovanni Lilliu, Dal betilo aniconico alla statuaria nuragica, p. 1764.[32]

This evolution suggests that besides the commissioners, also the sculptors of the statues of Mont'e Parma could have been Nuragic. In fact, within the Nuragic civilization craftsmen able to perform perfect stonework were certainly at hand, as demonstrated by the refined sacred wells and giant's graves built in the isodomic technique.[33] The ability in handling stones and the spread of sculpture in the round throughout Nuragic Sardinia, is also attested by the nuraghe models mentioned above and by sculpted protomes found in several sacred wells.[8]

Discovery site

[edit]The majority of the sculptures were thrown in pieces upon the necropolis found at Mont'e Prama, a low hill 50 m AMSL and strategically located in the very center of the Sinis Peninsula. Just one other fragmented sculpture – a human head – had been found elsewhere, near the sacred well of Banatou (Narbolia, OR). This site is ca. 2 km away from the nuraghe S'Uraki, and the head was found together with various ceramics finds, either Punic or Nuragic.[34][35]

Given the location of the numerous fragments at Mont'e Prama and of the unique one at Narbolia, it is speculated that the statues were originally erected near the necropolis itself or in a still unidentified place within the Sinis Peninsula, a region extending north from the Gulf of Oristano, between the Sea of Sardinia and the pond of Cabras.

The Sinis Peninsula was inhabited as far back as the Neolithic age – as attested by the remarkable archaeological area of Cuccuru s'Arriu . This site is well known for a necropolis dating back to Middle Neolithic (3.800–3200 B.C), where in the graves, a female idol in volumetric style was normally placed. Subsequently, all the cultural shifts that took place on the Island during the millennia, are attested in the Sinis region. Among these, particularly relevant is the Bell beaker culture, preluding the Bonnanaro culture (c. 1800 BC) that would eventually lead to the Nuragic civilization.[36]

Due to its fortunate geographic position and the considerable number of important settlements, such as Tharros, the Sinis Peninsula was a bridgehead for the routes toward the Balearic Islands and the Iberian Peninsula, related from time immemorial to Sardinia. The Balearic Islands were in fact home to the Talaiotic culture, similar under many aspects to the Nuragic and Torrean civilizations. The Sinis Peninsula is furthermore favoured by the proximity of Montiferru, a region that hosts an ancient volcano, site of important iron and coppers mines. The territory of Montiferru is also strictly controlled by a system of numerous nuraghes.[37]

A statue similar to those ones of Mont'e Prama was found at the Crabonaxia site, in San Giovanni Suergiu, Sulcis, located in Southern Sardinia.

Toponym

[edit]The hill of Mont'e Prama was covered in ancient times by dwarf fan palms, Chamaerops humilis, from which the name Prama, meaning "palm" in the Sardinian language, would originate.

The necropolis location is listed as "M. Prama" on the cadastral map of the municipality of Cabras, and on the 1:25000 maps of the Istituto Geografico Militare, sheet 216 N.E.[38] The letter "M." in the location name has been given several interpretations, such as Mont'e, Monti, Monte, and Montigru, all still in use in Sardinian language. Even a relatively small hill is referred to as a "mount", such as the Monti Urpinu (Cagliari) that is only 98 meters high on sea level.

In the past such a toponym, indicating the presence of dwarf fan palms on the spot, was recorded in some written documents. The theologian and writer, Salvatore Vidal, speaking of the Sinis Peninsula in his Clypeus Aureus excellentiae calaritanae (1641), reports the toponym Montigu de Prama. The Franciscan friar Antonio Felice Mattei, who in the eighteenth century wrote a historiography of Sardinian dioceses and bishops, mentions Montigu Palma as one of the localities within the Sinis peninsula.

Archaeological context and historical problematics

[edit]The exact date of the manufacture of the statues remains uncertain. The different hypotheses, brought forward by several scholars, encompass a time period between the tenth and eighth century BC, namely between the Final Bronze Age and the Iron Age. In any case, the sculptures are believed to originate within a period of cultural transformation, but profoundly rooted in the Late Bronze Age.[39]

In this timeframe the Sinis peninsula – and the entire Gulf of Oristano as well – was an important economical and commercial area, a fact well-attested by the high concentration of Nuragic monuments: at least 106 are officially recorded, comprising giants' graves (Tumbas de sos zigantes in Sardinian), sacred wells and nuraghes.[36][40][41] During the blooming Nuragic period, this number must have been much higher, given that the intense agricultural works have led, in the course of centuries, to the dismantling of several monuments.[34]

Beginning in the fourteenth century BC, the Mycenaean Greeks landed in the Sinis peninsula and elsewhere in Sardinia, whereas the first presence of Philistines is dated ca. 1200 BC. However, given that Philistines made use of Mycenenan-like pottery and the long-standing relationships between Crete and Sardinia, it cannot be ruled out that Philistines were present in Sardinia earlier than the thirteenth century BC.[42][43][44]

During this period the trading of oxhide ingots between Cyprus and Sardinia also began. This exchange of ingots lasted until the end of the Bronze Age.[45][46] The Sinis peninsula is considered to have been an important metallurgic area, given the proximity of Montiferru, controlled by numerous nuraghes.[34][37]

During the Final Bronze Age the Nuragic civilization underwent fast social transformations: nuraghes were no longer built, and many were no longer used or became temples.[47] Giant graves were no longer constructed, although many of them would be reused during the subsequent centuries. The same phenomenon occurs for sacred wells and other cultic places; some were abandoned, while others remained in use up to the Iron Age. There are no hints of invasions, wars among Nuragic communities, or destructive fires. Therefore, these important changes are attributed to internal factors, in turn determining a gradual cultural change, and social and territorial reorganization within the Nuragic society.[39][48]

Another relevant element was the trans-marine navigation journeys that Nuragics made toward several locations in the Mediterranean. Their presence is attested at Gadir, Huelva, Camas ( El Carambolo), Balearic Islands, Etruria, Lipari Islands, Agrigento (Cannatello), Crete, and el Ahwat.[49][50]

These attestations – pertaining to the time period between late Bronze Age and throughout Iron Age – are constantly increasing in number, due to new findings and studies in progress of Nuragic pottery, formerly classified as generic barbarian ware and, as such, preserved in repositories of museums without being further analysed.[42]

This dynamic scenario is further complicated by identification issues when attempting to distinguish between Nuragic people and the Sherden, one of the Sea Peoples. Textual evidence from cuneiform and reliefs of the New Kingdom of Egypt relate that Sea Peoples were the final catalyst that put into motion the fall of Aegean civilizations and Levantines states.[52] The Sherden apparently took part as mercenaries in several conflicts involving Egypt and often they are associated with Sardinia.

Scholars are still debating whether the Sherden were originally from Sardinia or whether they went there after having been defeated by the Egyptians. Egyptologists David O'Connor and Stephen Quirke on this subject have said:

From the similarity between the words Shardana and Sardinia scholars frequently suggest that the Shardana came from there. On the other hand, it is equally possible that this group eventually settled in Sardinia after their defeat at the hands of the Egyptians (...) In Papyrus Harris, the deceased Ramesses III declares that Shardana were brought as captivities to Egypt, that settled them in strongholds bound in my name, and that he taxed them all (...) this would seem to indicate that the Shardana had been settled somewhere (...) no further away from Caanan. This location maybe further sustained by the Onomasticon of Amenope, a composition dating to ca. 1100 BC, which lists the Shardana, among the Sea Peoples who were settled on the coast there. If is the case, then perhaps the Shardana came originally from Sardinia and were settled on the coastal Canaan. However, the Shardana are listed – in Papyrus Wilbour – as living in Middle Egypt during the time of Ramesses V, which would suggest that at least some of them were settled in Egypt.

— David B O'Connor, Stephen Quirke, Mysterious Lands. Encounters with Ancient Egypt, p. 112.[53]

Between the twelfth and ninth centuries BC, Sardinia appears to be connected to Canaan, Syria, and Cyprus by at least four cultural currents: the first two are the most ancient, they can be defined as Syrian and Philistine, and are exquisitely commercial in character. From the ninth century BC the third and fourth cultural currents began to appear in the West. One can be defined as "Cypriot-Phoenician", in that it was built by peoples originating from Cyprus and Phoenician cities; this movement had relationships with Sardinia but, most importantly, would lead to the founding of Carthage. The fourth current interested the Island to a largest extent, beginning from the eighth century BC,[42] with the urbanization of important centres such as Tharros, Othoca and Neapolis.[54][55][56][57]

The transformation of these coastal centres, mainly constituted of a mixed population with a large presence of Nuragic aristocracy – as demonstrated by the grave goods – gave a notable contribution to change the traits of the Island and of the Nuragic civilization, accompanying the decline of the latter until the Carthaginian invasion.[58] However, it is certain that during the seventh century BC the Sinis peninsula and the Gulf of Oristano were still controlled by Nuragic aristocrats [59][60] and that the end this supremacy coincided with the destruction of the Giants' statues.[61]

The necropolis

[edit]The fragments of the sculptures have been found on top of a necropolis situated on the slopes of Mont'e Prama, a hill towered by a complex nuraghe at its top. The necropolis is composed of wall-tombs, mostly stripped of grave goods. Those up to now investigated contained human skeletons placed in a sitting and crouching position, belonging to female and male individuals between thirteen and fifty years of age. Presently (2012), the mortuary complex can be divided into two main areas: the first one, parallelepiped-shaped, was investigated by the archaeologist Alessandro Bedini in 1975; the second one is serpentine-shaped and has been excavated between 1976 and 1979, by Maria Ferrarese Ceruti and Carlo Tronchetti.

A paved road, delimited by vertical slab stones, runs parallel to the latter mortuary area. The construction of the road is supposed to be contemporary to the monumentalization of the necropolis.[35] The Bedini excavations have unearthed an area containing thirty two slab-cist tombs, made of a stone different from the one used in the serpentine-shaped area.[35] The cist tombs were mostly without their cover slabs, as these were wrecked during centuries of agricultural activities in the area. This so-called "Bedini's area" appears to have undergone three phases of development:

- the first phase is represented by circular well-tombs, the most archaic ones; they are similar to those discovered in southern Sardinia at the Temple of Antas, dedicated to Sardus Pater Babai, the eponymous god of Nuragic Sardinians;

- the second phase should coincide with the cladding of the tombs with stone slabs;

- the third phase is contemporary to the necropolis excavated by the archaeologist Carlo Tronchetti – and should correspond to the placing of the statues.[62]

In the section excavated by Carlo Tronchetti, the beginning (spatial and chronological) of the necropolis is marked by a slabstone standing upright, juxtaposed with the first tomb at the southern side. The northern and more recent side is also delimited by a slabstone standing upright.[35] Beside the cover slabs of the serpentine-shaped layout, further small pits used for the deposition of human bones have been unearthed.[35] Due to the presence of the "Bedini's area", the last three tombs do not follow the natural pathway, but have been built on the side of the pre-existing burials.

As of 2012, the necropolis had not been fully excavated.

Hypotheses on the necropolis appearance

[edit]Due to the incompleteness of the excavations, it is not yet possible to determine the real appearance of the necropolis and grouping of the sculptures.

Some scholars have cast doubts about the original pertinence of the latter to the necropolis, in that the only evidence in favour of this fact would be the spatial contiguity between the statues and the mortuary complex itself.[56] This led others to hypothesize that the statues had been conceived as telamons to adorn a temple, close to the necropolis, but dedicated to the Sardus Pater. According to this theory, the temple with statues would have been erected to commemorate nuragic victories against the Carthaginian invaders, during the sardo-punic wars.[63][64] In this case, the statues would have portrayed the retinue or the bodyguards of the deity.[63]

Nearby the necropolis a rectangular structure has been erected, but this building is in concrete and clearly referable to the Roman age, even if it cannot be completely ruled out – due to the lack of excavations – that underneath the Roman building there was a nuragic megaron temple.[39] In any case, the presence of other sacral monuments in the vicinity of the necropolis is suggested by the finding of typical quoins employed in the construction of sacred wells.[56]

Other scholars dispute this theory and tend to think that the statues and necropolis were part of the same complex. In this view it is incorrect to hold as a sole basis for this hypotheses the closeness of the sculpture to the mortuary complex. In tomb number six of the "Tronchetti's area", a piece of scrap for manufacturing shields was discovered, leading to the suggestion that the statues had been sculpted on the site and expressly for the necropolis.[39]

Given some technical specificities, both the nuraghe models and the "oragiana type" baetyls, point to the same conclusion. In this case the necropolis and the statues could be reminiscent of giant graves. The layout of the complex recalls in fact the plan of a giant grave, and this suggestion is reinforced by the presence of baetyls, a feature typical of the ancient Bronze Age Sardinian tombs. This analogy would attest the ancient architects' will to perpetuate a link with the funerary traditions of their ancestors.[35][41]

As studies stand now, the authors do admit that even this last hypotheses is not supported by sound proofs – as far as the aspect and original composition of the statues-tombs complex is concerned. It has nevertheless been suggested that, if the hypotheses is correct, the sculptures would have been arranged at the east and west sides of the serpentine-shaped necropolis, to form a sort of gigantic human exedra reminiscent of the half-circle exedra of a giant grave. The boxers could have formed the most external part of this arrangement, whereas archers and warriors would have been located in the center, immediately next to the tombs. According to this hypotheses, the nuraghe models would have formed the crowning of the mound, being arranged on the cover slabs of the tombs.[39]

History of the excavations

[edit]The first find most probably belonging to the monumental complex of Mont'e Prama was recovered in 1965. It is a fragmented head in sandstone, found at the bottom of the sacred well of Banatou (Narbolia). Originally, the fragment of Banatou was held as Punic, given the large presence of Punic artifacts and the alleged absence of Nuragic statuary. The uncovering of the statues at the necropolis of Monti Prama had to wait almost ten more years.

According to the account of the two finders, Sisinnio Poddi and Battista Meli, the finding took place by chance in March 1974, while they were preparing the sowing of two adjacent lots that they rented yearly from the "Confraternity of Santo Rosario" of Cabras. Although the ground was sandy, it was rich in stony artifacts and column fragments, regularly brought to light by the plough. The two farmers continued to accumulate the pieces aside, not understanding their archaeological value.[65]

At the beginning of every sowing season the two finders noticed that the fragments of the previous year had considerably diminished, because they were removed from people aware of their historical value or employed as building material. It was the land's owner, Giovanni Corrias, that in front of a pile of stones and earth bearing the remains of a giant head, realized together with Sisinnio Poddi, that the head belonged to a statue. Corrias immediately informed the archaeologist Giuseppe Pau (Oristano), who in turn alerted the superintendence of Cultural Heritage for Cagliari and Oristano.[65]

During the early stages of discovery, the archaeologist Giuseppe Atzori insistently pointed out to the authorities the failure to fence the site. Most of the sculptures at the Center for Restoration and Conservation of Li Punti (Sassari) are missing their heads and the cause lies in the fact that the site was unattended and was plundered for a long time. The looting was focused on the best parts of the sculptures, principally the head with the enigmatic eyes. Only later the area was purchased and excavation campaigns began.[33]

According to the archaeologist Marco Rendeli, the history of the early researches is fragmented and defective and involves several archaeologists. Some of them performed short-term excavations (Atzori, 1974; Pau 1977), other researchers later carried out programmed investigations (Bedini 1975; Lilliu, Tore, Atzeni 1977; Ferrarese Ceruti-Tronchetti 1977).[41]

General characteristics and stylistic comparisons

[edit]On the whole the statues are highly stylized and geometrically shaped, similarly to the so-called "Daedalic style", well established in Crete during the seventh century BC. The face of the statues follows a T-scheme typical of Sardinian bronze statuettes, and of neighbouring Corsican statues.[35] The superciliary arch and nose are very pronounced, the eyes are sunken and symbolically rendered by two concentric circles; the mouth is incised with a short stroke, linear or angular.[66] The height of the statues varies between 2 and 2.50 meters.

They appear to represent boxers, archers, and warriors, all standing upright, barefoot and with legs slightly parted. Feet are clearly defined, resting on a square base.[66] A further characteristic is the presence of geometrical, decorative chevron (zig-zag) patterns, parallel lines, and concentric circles, in cases where it was not possible to represent such motives in relief. This happens both for the object and for bodily features. As an example, the braids coming down at the sides of the face are represented in relief, but the hair is rendered with incised fish-bone patterns. The archers’ brassards[b] are slightly in relief, while the details are rendered with geometrical engravings. These peculiarities – together with other evidence – demonstrate that the Mont'e Prama statues draw heavily on the Sardinian statuettes.[66] [67] The statues should have been painted, traces of colors have been recovered on some of them: an archer exhibits a red-painted chest, whereas a black colour has been found on other fragments.[68]

It is difficult to find parallels for these sculptures in the Mediterranean area:

- archaeologist Carlo Tronchetti speaks of fully orientalizing commissioners and ideologies.[69] Accordingly, other scholars – like Paolo Bernardini – identify in the sculptures Oriental influences, with some similarities to archaic Etruscan sculptures;[70]

- archaeologist Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway finds resemblances to Picentines, Lunigianian and Daunian sculptures of the 8th – 5th centuries BC, thus collocating the statues within the stylizing Italic and Aegean naturalistic current;[71]

- according to Giovanni Lilliu the sculptures belong to the geometric style, underscored by the engraved ornamental signs, and take direct inspiration from the Sardinian statuettes of the "Abini-Teti" type. According to the distinguished archaeologist it is thus profoundly wrong to assign the statues to the Orientalizing period, with the possible exception of the colossal body structure;[72][73]

- archaeologist Marco Rendeli considers unsatisfactory all the attempts to compare the Sinis statues to those found in Hellenic, Italic, and Etruscan areas. According to him the correct approach implies understanding the statues as a unicum, originated from interactions between Levantine artisans and Nuragic commissioners. This uniqueness is confirmed also by the peculiar well-tombs of the necropolis, finding no parallels in other sites, either in Western or in Eastern Mediterranean.[74]

Boxers

[edit]Boxer is the conventional term referring to a category of Nuragic bronze statuettes, furnished with a weapon similar to the cestus, that wraps the forearm with a rigid sheath, probably metallic.[76]

The panoply of the warrior or wrestler – depending on different interpretations – also comprised a semi-rigid, curved rectangular shield.[76]

It is generally believed that the boxers were taking part in sacred or funeral games in honor of the deceased, as seen elsewhere in the Mediterranean area.[76][77]

Boxers make up the most numerous and uniform group within the Sinis statues, showing only minor variations in size and unimportant particulars.[66]

Boxers are invariably represented bare-chested, with engraved navels or nipples; and they wear loin-cloths with the rears trimmed to a triangle, a typical feature of Sardinian bronze boxers and warrior figurines, such as the "archer of Serri" (from Serri, the findspot).

The upper part of the chest is protected by a belt from which –in some cases – shallow grooves depart, depicting the strings used to tie the loin-cloth.

The boxer heads are covered by smooth caps. Sleeves running from the elbow down, presumably originally in leather, protect their right arms. The sleeve terminates with a rounded cap into which the weapon, in metal or other material, was inserted.

The rectangular, curved shield is held by the left arm and raised above the head.[35][78] It was most probably made of leather or other flexible material, given that it is bent on the long sides. Furthermore, internally it is framed with wooden twigs, whereas the external part is characterized by an embossed rim all along the perimeter. The shield appears to be fixed, on the internal side, to an armband decorated with chevron patterns, worn at the elbow of the left arm.[76]

The figure of the boxer is attested in bronze statuettes, among which – beyond Sardinian specimens – is the notable figurine found at Vetulonia within the "tomb of the ruler".

The most similar bronze figurine, however, both for typology and for distinguishing marks, is the statuette from Dorgali.[66][75][79]

Archers

[edit]The fragments have, up to now, allowed restoration of five statues for this iconographic type.

Archers show more variation than boxers, despite their much smaller number.[66] The most frequent iconography represents a male warrior dressed in a short tunic. A square pectoral with slightly concave sides is worn on top of a tunic. In some cases the tunic reaches the groin, in other instances the genitals are left exposed.

Beyond the pectoral, other elements of the panoply are represented, such as gorger and helmet. The different fragments of upper limbs often show the left arm furnished with a brassard holding a bow, while the right hand is extended forward like in the typical gesture of salutation commonly seen in Sardinian bronze statuettes.

Legs are protected by peculiar greaves with notched borders, hanging by laces underneath the tunic; a leg guard shows a figure-of-eight outlined in its back, while a sandal is occasionally depicted on a fragmented foot.

Depiction of weapons is extremely detailed. In analogy to bronze figurines, the quiver is sculpted on the back, in a very refined way.[35][66]

It is furthermore evident that there are two types of bow:

- a heavy one with a quadrangular cross-section and cross-ribbed

- a lighter one with circular cross-section, possibly pertaining to a mixed weaponry

Nuragic soldiers included archers, swordsmen, and warriors bearing a mixed weaponry, consisting of a bow and a sword. Bow and sword may be outstretched at the same time, such as in the "Uta-type" bronze figurines (from Uta, the findspot), or the sword may remain in the scabbard while the archer is shooting an arrow.[80]

The quiver-scabbard pair is visible in at least one statue [66] and finds parallels either in the "Uta" and in the "Abini-type" bronze figurines (the latter named after their finding spot, the Nuragic sanctuary of "Abini" in Teti).[81] Archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu stressed in particular the similarity between the crescent-shaped hilt of the Mont'e Prama statue and the one held by the archer of Santa Vittoria di Serri, wearing the same loincloth, trimmed in the back like a tailcoat, as the Monte Prama boxers.[82]

Archer faces are similar to those of the boxers, with the hair gathered up in braids coming down at the face sides. The head is protected, up to the nape, by a calotte-shaped, crested, and horned helmet, with the ears left free.

Several fragments show that the horns are slightly curved and bending forward, of uncertain length and pointed at the end (different from the warriors); furthermore, there are traces of a support, obtained from the same stone, joining the horns approximately at their half-length.[76]

The bronze figurine most similar to the archers of Mont'e Prama appears to be the archer from "Abini".[79]

Warriors

[edit]This iconographic type – very often represented among the Nuragic bronze figurines – has been reported only twice among the Mont'e Prama statues, plus a third possible case, of which only one is in a good state of preservation. However, a reassembled shield, not assigned to any of the former three specimens, and numerous other fragments of a shield and (possibly) of a torso, suggest that the number of warriors was larger.

Initially, the fragments of round-shaped shields had been attributed to archers, but later the hilt of a sword and similarities of the shields geometrical patterns to those of some bronzetti, led to postulate the presence of one or more statues of warriors.[83][84]

Warriors differs from archers essentially through their garb.

The best preserved head exhibits an "envelope-shaped", crested, and horned Nuragic helmet that – like archer helmets – must have presented the typical long horns portrayed in bronze figurines. Several small cylindrical fragments have in fact been found during excavations. Once recomposed, some of these horns appear to bear small spheres at their terminal ends, like in some bronzetti, either anthropomorphic (in this case only warriors, never archers) or zoomorphic.

The best preserved warrior statue is among the most striking pieces of Mont'e Prama. Besides the horned helmet – whose horns are broken – it is marked by the presence of an armour with vertical stripes, short on the back, but solid on the shoulders and more expanded on the breast.

By analogy with armours visible on several bronze figurines, it is thought that the breastplate was built of metal strips applied on hardened leather. A panel, decorated and fringed, comes out from the lower part of the breastplate.

The shield is represented in a very detailed way, with chevron patterns reminiscent of geometrical drawings on pintaderas, and with radiating grooves that converge toward the shield-boss.[76]

The bronze figurine most similar to the warriors of Monte Prama is the one found at Senorbì.

Nuraghe models

[edit]Multi–towered nuraghe were the second highest megalithic constructions ever built – after the Egyptian pyramids – during the Bronze Age in the Mediterranean protohistoric area.[85] The central tower from nuraghe Arrubiu (Orroli), one of the largest in the Island, reached the height of thirty meters and the general plan of that monument consists of at least nineteen towers articulated around several courtyards, occupying an area of approximately 3000 meters square excluding the village that lies outside the walls.[86] It was the result of a unified design covering both the keep and the pentagonal bastion all made at the same stage in the fourteenth century BC.[85]

A nuraghe model is defined as the down-scaled, three-dimensional representation of Nuragic towers and castles, for sacred or political purposes. In analogy to the full-sized monuments, models can be divided into two general categories:

- complex nuraghe models, with a higher central tower surrounded by bastions and four further towers, the so-called quadrilobate (or multi–towered nuraghe)

- models of simple, single-towered nuraghe

Mont'e Prama is the archaeological site where the largest number of nuraghe models has been recovered.[87]

At the restoration center of Li Punti it has been possible to reconstruct five models for complex nuraghes and twenty for simple nuraghes. The models of Mont'e Prama are characterized by their notable size, up to 1,40 m in height for quadrilobates and between 14 and 70 cm in diameter for the single towered specimens,[35] and by some unusual technical features.[87]

These big sculptures are modular, and unlike the remaining nuraghe models from Sardinia, in that the shaft of the mast tower is joined to the top part through an inter-space, whose pivot and binder is constituted by a core of lead.[87] Upper platforms have been faithfully represented in the various nuraghe models. On the top of the towers a conical, dome-shaped element has been sculpted, indicating the covering of a staircase leading to the platform.[88][89][90]

Several architectural elements have been represented with engraved signs. The parapet of the platform has been portrayed with a single or double row of incised triangles, or with vertical lines, similar to miniaturized nuraghes from other Sardinian sites, e.g. the high-relief from nuraghe Cann'e Vadosu and the nuraghe model from the meeting hut of Su Nuraxi in Barumini.[91] Also the big slab-stones supporting the platforms have been rendered with decorative signs. The stone brackets and their function have been depicted by means of parallel incised lines or grooves and the blocks – abundantly found in archaeological sites after the collapse of top parts – confirm the perfect matching of these models with the Nuragic architecture of Middle and Recent Bronze Age.[87]

Oragiana baetyls

[edit]The word "baetyl", probably from Hebraic Beth-El ("house of God"), originally denoted sacred stones of simple geometric shape and aniconic. In analogy to the religious meaning borne by their oriental counterparts, it is thought that for the Nuragics, they could represent the deity's house or the deity, in an abstract and symbolic way. This is suggested by their constant presence in the cultic places of Nuragic civilization, from sanctuaries such as Su Romanzesu in Bitti, to giant graves.

These artifacts can be divided into cone-shaped and truncated cone-shaped baetyls. The distinction is chronologically relevant, in that the latter are more recent and pertain to isodomic stone block giant graves.[92][93][94] At Mont'e Prama truncated cone-shaped baetyls with holes, of the so-called "Oraggiana" (or "Oragiana") type, have been found. According to archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, the holes could represent the eyes of a deity, protecting and watching over the tombs.[95][96] Nuragic baetyls are symbolic items typical of the Middle and Recent Bronze Age, sculpted approximately from the fourteenth century BC.

Their presence in the Mont'e Prama necropolis has been explained by Lilliu with two alternative hypotheses: the baetyls originated from a wrecked giant tomb or they are reproductions of more ancient specimens, due to a wish to preserve an ancient line of Nuragic tradition, in a sort of nostalgic commemoration.[69][97] The double row of holes noticed in one of the baetyls from Mont'e Prama, unattested elsewhere in Sardinia, suggests that these artifacts are the same age as the necropolis. Some scholars believe in fact that they were expressly produced for the Monti Prama complex.[94]

The dating problem

[edit]The construction date of the statues is the main problem concerning the site of Mont'e Prama, but no less important are the historical implications that can derive from the certainty of the date of destruction and abandonment.

Scientific investigations dating back to 1979 have not solved these problems and doubts are still raised despite the latest (2015) radiocarbon dating.

Absolute dating of the buried

[edit]

Of the more than 150 tombs, thirteen are those whose osteological remains have been dated until today (2021) with the carbon-14 method. Previously the chronological data was provided by the stratigraphic excavation (in some limited areas), by the stylistic comparison with the bronze statuettes, as well as by the indications of various finds (pottery, scarab, and fibula). However, according to the scholar Marco Lazzati ... the archaeological stratigraphy, in any case, provides only relative dates, indicating in which order the events occurred, without telling us" when" they took place."[98](p 3)

Absolute dating offers a fundamental contribution to the understanding of the site because it provides researchers with an objective and reliable chronological data capable of overcoming hypotheses based exclusively on formal factors, hypotheses once favored by art historians, but almost always lacking the necessary objectivity and reproducibility.[98]

Radiometric dating is therefore essential to indicate with the greatest possible precision the events that affected the beginning, development, and end of the necropolis and therefore, of the statues. According to the archaeologist Mauro Perra: In the first place, the C14 datings proved those who argued that the chronology of the necropolis could not be related exclusively to the VIII-VII century BC, but that it was referable to rather broad chronological horizons between the Recent Bronze and the Early Iron, right.[99]

The 14C method was applied to collagen samples that were poor from a quantitative point of view, but excellent from a qualitative one. The samples have an optimal carbon to nitrogen (C / N) ratio of 3.2–3.3, which being within the range 2.9–3.6, indicates collagen that is "not degraded or contaminated"[100]

To confirm the extreme reliability of the material, it should be emphasized that the δ13C [c] measured at the University of Groningen was found to be identical in two cases to that measured by the University of Cambridge. In one case, that of tomb twenty from the "Tronchetti sector", the discrepancy was just 0.2%. Even the values of the sub-samples that were taken from it do not show such discrepancies as to highlight problems.[100]

The dating of the statues through bone remains is made possible by the presence of many sculptural fragments in the tombs of the more recent phase. Above the small plate that sealed the bones, a fragment of a warrior shield (tomb number six) and a statue finger (tomb number twenty-eight) were identified; other fragments of organic limestone pertinent to statues or models of nuraghe) were found in tombs number four, six, twenty-four, twenty-five, twenty-six, twenty-eight, twenty-nine, thirty, I-bis, two-bis of the "Tronchetti sector".[101]

In the "Bedini sector" sculptural fragments were recovered above the tombs of the most recent phase, but not inside them, probably due to the upheavals carried out during the night by clandestine excavations while the official excavations were still in progress. However, in the same sector a sculptural fragment was found, probably of a model of nuraghe, inserted within the well tomb i of the oldest phase of the necropolis.[102] Having found the presence of scraps from the creation of the statues in sealed tombs, it indicates – according to scholars – a greater antiquity of the statues when compared to the burials.

- The first analyzes were carried out on the bone remains of three individuals, whose tombs (number eight in the "Bedini sector" and tombs number one and twenty in the "Tronchetti sector") all belong to the intermediate phase of the necropolis, a phase during which – according to the excavators of the site – Mont'e Prama was monumentalized with the affixing of the statues.[103]

- Tomb N. XXXI is among the most ancient datings, in this case the deceased dates back to 1246 BC ± 57 years.[104] The tooth MA115, of which the tomb of origin is not given, and the tomb "n" of the sector have a range between 1230 BC and 1239 BC.[105]

- In addition to the aforementioned tombs from the intermediate period, there is the last Nuragic burial that occurred at Monte Prama within the J tomb. It was the subject of two different radiometric tests, but with identical results, placing the last Nuragic burial at the beginning of the Punic conquest of the island.[104]

Despite the reliability of the analyzed collagen and of the procedures used to study it, controversies have arisen even regarding these data:

- according to the scholar Luca Lai, the recent C.14 dating would impose a "modification of the assumptions of the current interpretations of the site"[106]

- for the archaeologists Marco Minoja and Carlo Tronchetti, the C14 method alone is not sufficient: "to modify a functioning and tested system, relying only on partial data that do not lead to the construction of a coherent alternative system"[107]

- for the archaeologist Luisanna Usai: "if one were to accept the close connection between statues and burials and in particular those of the Tronchetti necropolis, according to the calibrated radiometric datings, the sculptures should be dated to the 11th-10th century BC"[108]

Chronological and stylistic relationship between the statues and the bronze statuettes

[edit]The linguistic relationship is so close, between statues and figurines, as to suggest that the latter are small reproductions of the former and that there was a continuous intertwining, a permanent communication, in the artistic culture of the time, between stone sculptors and bronze artisans.

— Giovanni Lilliu, Dal betilo aniconico alla statuaria nuragica, p.1764

Starting from the considerations of the archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu on the relationship between statues and bronzes, in the archaeological field the debate is very heated among those who attest to the beginning of bronze production starting from the Iron Age, and in particular from the 9th century BC, and the supporters of the production of bronzes starting from 1100 BC to 1000 BC as proved by the stratigraphy of the Sacred Well of Funtana Coberta in Ballao (CA).[109][110][111] This last dating is also corroborated by the findings made during the excavation campaign on the Giant grave of Orroli, not far from the nuraghe complex of Arrubiu, where in an intact archaeological context they found bronze statuettes dated between the 13th century BC and the 12th century BC[112]

Given the very close similarity between bronze statuettes and statues, the dilemma arises whether the statues were inspired by the statuettes (in the case of the statues being older than the statuettes) or if the statuettes are the model that the Nuragic aristocracy imposed to the artisans (in the other case the statues being younger than the statuettes): In the second case the statues could be much less ancient than the bronze statuettes.

These differences among scholars are not resolved by the discovery of the new statues of boxers comparable to the warrior-priest of Cavalupo di Vulci. In this regard there are two opposing trends of thought:

- For some scholars, the bronze statuette of Cavalupo di Vulci is the cornerstone on which to anchor the dating of the entire Nuragic production. In fact, it was found in a closed context dated between the ninth and eighth centuries BC and since, so far, no other absolute dating has been carried out in Sardinia in closed contexts, the small statue of Cavalupo is the main chronological reference for all the bronze statues found in the contexts of the island.[113][114]

- Another group of scholars believes that the bronze statuette of Cavalupo di Vulci "only represents a generic terminus ante quem for the chronology of the bronze statuettes";[115] it constitutes a closed context but also a false context – in the sense of falsifying the dating of all the other bronzes – since the production and export from Sardinia to Etruria took place in much earlier times than its deposition in the Vulci tomb.[116]

In any case – according to the archaeologist Marco Rendelli – the close stylistic relationship between the bronze statuettes and the statues of Mont'e Prama proves that the two forms of art must be, at least partially, contemporaneous.[117]

The Egyptian scarab from tomb number twenty-five

[edit]The archaeologist Carlo Tronchetti is the author of a first attempt to date the scarab found in Mont'e Prama. The erroneous suppositions on the material, believed to be of bone or ivory, and the attribution to the category of Hyksos pseudo scaraboids led the scholar to erroneously date the artifact to the seventh century BC. In fact, recent analyzes have shown how the artifact is made of fired and glazed talc stone, ascribing it to the typical production of the New Kingdom.[118]

The interpretation of the iconographic motif at the base of the artifact is debated. For some scholars it would be the stylization of a lotus flower; for others the engravings are part of the "encompassed central X cross" decoration. In any case, even the decoration cannot be compared with that of the Phoenician or Egyptian and Egyptizing scarabs of the seventh – sixth century BC,[119] while it finds the most stringent comparisons with two other specimens from the Palestinian localities of Tall al-Ajjul and Tell el Far'ah (S),[120] localities considered to be interested in various periods both from the Egyptian presence and the Mycenaean and Sherden mercenaries’ one.[121][122] The Sherden, in particular, have been associated to the Nuragic Sardinians by many scholars.[123][124][125][126]

The scarab of Mont'e Prama is not the only Egyptian scarab found in a Nuragic context: archaeologists found them in the Nuraghe Nurdole in Orani too,[127] in the inhabited area of the Complex of Sant'Imbenia in Alghero[128] in the Nuragic complex of S'Arcu 'e Is Forros in Villagrande Strisaili.[129]

According to some scholars, it is necessary to underline the general unreliability of the scarabs for the purposes of the chronology of the sites and monuments in which they were deposited. There are many documented cases of scarabs that have remained in circulation even for almost a millennium from the date of production, such as the New Kingdom scarabs found in Carthage.[130]

The pottery of Mont'e Prama

[edit]The dating of the ceramic fragments found in the necropolis of Mont'e Prama is controversial due to the general difficulty in distinguishing the pottery belonging to the Final Bronze Age from that of the Nuragic Iron Age. In fact, in the sacred wells, megara, sanctuaries and sacred caves, both the finds from the foundation period (1350–1200 BC) and those of the final bronze (1200–950 BC) are present together, and that pollutes the Iron Age strata.[131]

However, in the recent excavations carried out in 2014 and 2015, the necropolis was confirmed to a more ancient dating, approximately, at least 1250 BC, due to the increasingly conspicuous discovery of cups belonging to the characteristic production of the Nuragic Recent Bronze inserted in the simpler funerary wells and belonging to the most ancient funerary ritual.[132]

According to the archaeologist Giovanni Ugas, a miniature vase found in one of the oldest tombs in the sector excavated by the archaeologist Alessandro Bedini, constituting the oldest part of the necropolis, can be compared with another miniature from the [[Nuragic sanctuary of Santa Vittoria | sanctuary of Santa Vittoria of Serri]] and dated to the eighth century BC[133]

This comparison has been criticized by other scholars as the jar of Santa Vittoria has X-shaped handles, while the miniature of Mont'e Prama has rod-shaped handles, finding better comparisons with numerous other examples from the Sinis and Cabras, both from unknown locations, and from scientifically investigated contexts such as the sanctuary cave of Su Pirosu Benatzu of Santadi, of the nuraghe Sianeddu in the Sinis di Cabras, the sacred well of Cuccuru S'Arriu (first phase) in Cabras and of the giants’ grave of Sa Gora'e sa Scafa in Cabras. These contexts and their miniature vases can be dated to the Recent Bronze.[134][135]

Both the faired bowls and the convex-lipped bowls found in the part of the necropolis excavated by the archaeologist Carlo Tronchetti, considered less ancient than the portion excavated by Alessandro Bedini, may belong to both the Final Bronze and the early Iron Age.[136] The archaeologist Giovanni Ugas, while recognizing the beginning of this vascular production in the Final Bronze, considers it preferable to date the artifacts of Mont'e Prama to the Iron Age.

Of the opposite opinion is the archaeologist Vincenzo Santoni, for whom the set of ceramics found in Mont'e Prama finds sure confirmation in numerous other Nuragic settlements of the Sinis and Cabras (Nieddu, Crichidoris, Muras, Riu Urchi), in votive deposits (of Corrighias e di Sianeddu), in recent discoveries at Tharros by the archaeologist Enrico Acquaro, at the nuraghe Cobulas of Milis, all datable to the Final Bronze.[137] For both the archaeologists Giovanni Ugas and Vincenzo Santoni the ceramics of Mont'e Prama find precise comparison in the Nuragic clay finds found at the Lipari castle, a site already frequented by the Nuragics during the so-called Ausonio I in the Recent Bronze but which, but which, regarding the vascular forms, present more precise comparisons with the site of Mont’e Prama in the phase of the so-called Ausonio II of the Final Bronze.[138]

In the excavations carried out in 2014–2015, the dating of simple well tombs to a more ancient date, of at least the end of the Recent Bronze (about 1250 BC), is confirmed:

- Typical pottery of this period was found in the B/2014 well, with stringent comparisons to the settlement of Brancu Maduli in Gesturi and above all in the silos de Sa Osa (Cabras); a truncated Recent Bronze cone cup (from about the 1300 BC), with comparisons in the Nuraghe Nolza of Meana Sardo and in that of Nuracraba or of the Rimedio – Oristano.[139]

- The single-handled cup of the T tomb in the "Bedini" sector finds stringent comparisons with materials found in the Recent Bronze contexts of the Oristano area, such as the Nuracraba nuraghe, the lower layer of the Cuccuru ‘e is Arrius well, the N well of Sa Osa and the Sacred Nuragic spring of Mitza Pidighi in Solarussa.

- Identical comparisons are proposed for a similar cup found in the E/2014 tomb of Mont'e Prama, with a straight vertical rim, rounded bottom, slightly convex bowl and a two-lobed straight handle.[132]

- Another example of Recent Bronze nuragic pottery was found in the W/2018 well, located in the land north of the Confraternity of the Rosary about six meters from the 58 fence. Just like in the J and T tombs, the vase was found under the skeletal remains, flattened on the bottom of the well but almost perfectly reassembled, with the edge upward. The vessel has the shape, surface treatment and color typical of the Recent Bronze Age: the closest comparisons are found in the N well 'of Sa Osa 62, in the Nuracraba nuraghe and in Mitza Pidighi.[132]

Dating of the A, A1, and B buildings

[edit]According to archaeologists Alessandro Usai and Silvia Vidili, in the buildings investigated in 2015 and 2016, the structures A, A1, and B, constitute a progressive chronological sequence confirming the rise in the dating of Mont'e Prama. The B building (Early Iron pottery (850 -900 BC)) leans on the A1 corridor (Nuragic Early Iron / Final Bronze pottery, 830 BC-950 BC) and the circular A building; B is therefore more recent than both A1 and A; and building B was not only built after building A but also after the construction of the A1 atrium.[140] The materials of the A1 building, being attributed to the Early Iron-Final Bronze, present a significant uncertainty in the dating, placed between 830 BC and 950 BC.[141]

The exact construction date of the A building is unknown, however it is certain that it is more ancient than the A1 corridor since the masonry of A1 is leaning against the wall of A. As this building is older than A1 and B, it is possible that A was already built at the beginning of the Final Bronze if not earlier; this uncertainty is caused by the reuse in the Nuragic age but especially in the Punic age;[142] during these periods the reuse (especially the Punic one) caused the removal of all the Nuragic materials making it impossible to date it through the context;[143] re-use can delete the oldest phases with the overlapping of more recent materials, giving the impression that the building is much less ancient than its real dating; cases of reuse and restructuring pose the risk of a falsified chronology.[144]

Relative and absolute dating of Nuraghe models

[edit]For the nuraghe models the dating difficulties – and the consequent controversies between scholars – are similar to those for bronze statuettes and pottery.

The models of Mont'e Prama – according to the archaeologist Alessandro Bedini – would have been sculpted in a period preceding that of the large statues, but in any case not before the 9th century BC.[145][146]

Other scholars – believing this proposal to be equivocal – assign the Mont'e Prama models to 10th century BC, during the terminal phase of the Bronze Age.[147] This latter hypothesis has recently received support from the only C14 dating available for these objects.

During the excavations inside the D tower of the Arrubiu nuraghe of Orroli, acorns were found in the same stratigraphy in which a basalt model of nuraghe was found. The C.14 exams carried out at the University of Madrid date this level of presence between 1132 BC. and 1000 BC.[147][148] This absolute dating seems to be confirmed by the excavations carried out in the Matzanni cult complex at Vallermosa, (Cagliari). In this site the sacred well A contained a model of a nuraghe, a ram, and human feet of a small bronze statuette, in a Final Bronze context.[147][149]

Date of destruction

[edit]The date of destruction (or the date of formation of the landfill) is determined by the presence of various fragments of Punic amphoras underneath an archer bust, and other fragments of statues in the deepest and therefore older parts of the landfill, which excludes their infiltration in later periods.[150][d]

The Punic fragments can be dated with certainty to the end of the 4th century BC or the beginning of the 3rd century BC; the Punic ceramic fragment constitutes the chronological limit ante quem non.[151] Near the s'Uraki nuraghe, in the sacred well of Banatou in Narbolia, a fragment of a statue was found together with Punic votive statues and mixed Punic and Nuragic pottery, but unfortunately the difficulties in which the excavation took place do not allow a reliable dating of the find.[152]

The last burial that took place in the necropolis of Monte Prama seems to be that of tomb J. Although it contains pottery dated to the tenth-eleventh centuries BC the buried one was dated using the 14C method in two different tests, and both placed the last Nuragic burial in the fifth century BC or in the fourth century BC, therefore in full Punic age; the difference between the date of the pottery and of the buried body could be explained by a reuse of the tomb in the Punic age[153][154]

The date of the fourth century BC is also connected to the Punic intervention in the A building; this environment was in fact emptied of Nuragic materials up to the foundation level of the structure and even further down. Paradoxically, despite being older than the A1 and B rooms, the A building only contains Punic material from the fourth century BC, when it was used by the Punics, perhaps, as a kitchen and home.[155]

Finally, at Mont'e Prama tombs and a fragment of stele of Tanit were found, similar to those found at the Punic necropolis of Tharros and at the sacred well of Cuccuru is Arrius, also from the Punic age. Coeval to the destructive intervention of the Punics, near Mon'te Prama are the destruction of the necropolis and Nuragic sanctuary at Antas (replaced by a temple to the Punic god Sid Addir) and at Tharros.[156]

These three interventions are to be read as a strategy for conquest made by Carthage. Another hypothesis separates the moment of the formation of the landfill (fourth century BC) from that of the destruction which would have occurred rather in the seventh century BC, by the hands of the Phoenicians residing in Tharros; this thesis doesn't have a great consensus behind it since it is believed that in the Phoenician age, in a period between the fifth and seventh centuries BC, the idea that the Levantine settlements in the gulf area, from Tharros to Othoca to Neapolis, had developed an internal dynamic, an organization and a propulsive capacity such as to reverse the balance of power to the detriment of the indigenous element is very doubtful.[157]

Ideological aspects of the monumental complex

[edit]In general, scholars see in the Mont'e Prama complex a self-celebration site for a Nuragic aristocratic elite and its idealized, heroic warriors.[158] Its strategic location within the Gulf of Oristano would thus aim to transmit to foreign visitors, especially the Phoenicians settled in Sardinia, a message of dominion and power over the island.[35]

Nuraghe models found together with the statues can be seen both as sacred symbols and as a claim for Nuragic identity:

- as symbols of identity, the various nuraghe models sculpted around the tenth century BC, would be a downright totem of the Nuragic world, besides being a symbol of power like the statues. Nuraghe models are in fact present in big meeting or "reunion huts" of several nuraghes, among which su Nuraxi at Barumini;[87][159]

- as sacred symbols, nuraghe models could have been seen as guardians for the dead of a necropolis and/or as ritual devices, given their presence as altars in all the great Nuragic sanctuaries.[87][160] This sacred/political ambivalence, the depiction of nuraghes in everyday objects such as buttons, smoothing tools, and others, attest through the so-called models, a real cult of the Nuraghe monument.[161]

Despite a general consensus about values and ideologies underlying the monumental complex of Mont'e Prama, political implications and artistic influences are still hotly debated. As for political significance, some scholars tend to see in the small number of warriors, with respect to archers, a sign of military and political decay of the Nuragic society, caused by the establishment of Phoenician centers in Sardinia. This would be mirrored by the import and adoption of Levantine ideological models and by assignment of the statues to the orientalizing period spreading throughout the Mediterranean area during the eighth century BC.[35][66][69]

Recent researches (2010) have nevertheless demonstrated that the old idea of a Nuragic civilization collapsing upon the arrival of Phoenicians and their colonization of Sardinia, is completely outdated. Phoenicians started to arrive in Sardinia around the ninth century BC, in small number, and remained scattered along the coastline. This period was the heyday of Nuragic society and Phoenicians started to cooperate with the Nuragics that, in turn, continued to administer harbours and economic resources.[48]

According to archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, the statues were not erected during a period of political decay, but during a great cultural revolution affecting aristocracy, economy and politics. The sculptures would thus reflect an independent and sovereign condition of Nuragic people.[158]

Furthermore, the geometric "Abini-Teti style", rules out a possible placement of the statues within the orientalizing culture and period, only appearing in bronze artifacts of the seventh century BC.[161][162] It is thus correct to speak of a Proto-Sardinian, oriental artistic trend.[163] According to Giovanni Lilliu the statues belong to an indigenous artistic and political climax, with an almost urban character.[164]

All these discrepancies among scholars are largely related to the chronological problem.[161]

Possible manufacturing techniques

[edit]According to art historian Peter Rockwell, several metal tools have been used, probably made of bronze.[4] In particular these tools can be noted:

- a stone-cutter's chisel, that is a chisel with blades of diverse sizes

- an implement similar to a hand scraper, employed like or together with abrasives

- a dry-point to carve sharp lines in detail

- an instrument to produce holes, similar to a drill, whose usage by Nuragic people has been proven by archaeological finds

- a tool similar to compass to engrave circular lines, such as those of the round eyes. About that tool Peter Rockwell wrote that:

...each eye is made of two concentric circles that seem to be perfect circles. One could imagine that this was done with a compass, but there is no sign of the compass in the center of the eye. We are faced with statues that although it seems a bit primitive in the project, have been carved with a skill that is equal to that of much more advanced periods.

— Peter Rockwell, Il mistero dei Giganti.[165]

It is sure that Nuragic civilisation knew the compass because one iron compass was found at "Nuraghe Funtana", near Ittireddu.[166]

- a tooth chisel, that is a stone-cutter's chisel having a toothed and sharp edge, particularly suitable for marble sculpture, leaving the most interesting traces on the Giants. This tool was hit keeping it slanted on the surface, in order to create a first polishing with grooves of different tightness. According to scholars, this technique was introduced in Greece not before the sixth century BC.[4]

Other examples of sculptures

[edit]Other similar sculptures are the finds from Viddalba (Ossi), held at the Museum Sanna of Sassari, and from Bulzi, of which not even the exact provenance is known. They are characterized as being halfway between statues and baetyls.[29]

The crested and pointed helmet again draws heavily on bronze figurines, in particular on the "archer of Serri" and on an archer found at the megaron temple of Domu 'e Urxia.[167] The sculptures are in limestone, the face has the familiar T-scheme, with two holes representing eyes. The crested helmet with front visor, is furnished with two hollows into which limestone horns, that have left some remnants, were fitted. If the crest recalls the helmets of some Nuragic bronzetti, the hollows hosting horns are in common with statue-menhirs of Cauria and Filitosa, dated to 1200 BC and assigned to the Torrean civilization, closely related to the Nuragic one.[168]

According to archaeologist Paolo Bernardini, monumental statuary appears also at the site of "San Giovanni Sergiu", in South Sardinia, most probably linked to a necropolis. At the site, a surface survey among the stones piled from a field tillage uncovered a head carved in sandstone, surmounted by a tall and bent headgear, embellished with tusks. The lineaments, extremely damaged, still preserve two nested circles representing eyes, identical to those of the statues of Mont'e Prama, and a sharp chin. Other fragments from the same site seem to belong to a human trunk with a cross belt, with a clear image of a small palm tree, sculpted in relief and partially painted in red.[169]

Possible fragments of statues have been found in the sacred building of "Sa Sedda 'e Sos Carros" (Oliena), dedicated to the cult of water; some quoins, used as raw stone material to level out the stone floor, show traces of relief decorations reminiscent of those on the fragments of shields from Mont'e Prama; this possible link is reinforced by the finding of a putative fragment of a foot.[170]

See also

[edit]- History of Carthage

- History of Sardinia

- Late Bronze Age collapse

- Nuragic bronze statuettes

- Nuragic civilization

- Sea Peoples

- Tharros

Notes

[edit]- ^ Specific baetyl with quadrangular recesses in the upper part. They owe their name to the Giants' grave of Oragiana, (Cuglieri). Belongs to the category of baetyl "with breasts" and baetyl "with eyes", depending showing in relief sculpted breasts (Giant's grave of Tamuli; Macomer), instead of circular or square holes (Giant's grave of Oragiana). Those founds at Mont'e Prama are with double row of recesses.

- ^ Quadrangular plate made of leather or other material that covered part of the arm; was used as wrist–saver by archers and to reduce the impact of the bow when shot. Related to the Bonnanaro or Bell–Beaker culture, has also been found in stone or bone with four holes at the ends. The brassard was attached to the wrist with strings passing through those four holes.

- ^ "δ13C" ("delta-C13") is defined as the variation (expressed in "per thousand") of the 13C / 12C fraction of the sample under examination compared to that of the international standard VPDB (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite ) consisting of fossil calcium carbonate. It is necessary to measure this variation to correct the 14C results for the effects of isotope fractionation. The δ13C can also give indications about the environment (terrestrial, fluvial, or marine) in which the being from which the sample to be dated lived, as well as about its area of origin and even on possible food imbalances.[98](p 9)

- ^ "... statue e tombe erano dunque originariamente in connessione, non si vede il motivo per cui una tale mole di frammenti dovrebbe esser stata spostata da un sito più lontano e distante per essere collocata esattamente lì. La discarica è avvenuta nel corso dell'avanzatissimo IV secolo a.C. se non ai primi decenni del III sec. a.C. come indica la ceramica più tarda trovata all'interno del cumulo dei pezzi di statue anche con frammenti di grandi dimensioni trovati nella parte più bassa del giacimento. Un ampio frammento di orlo di anfora Punica rinvenuto al di sotto di un torso ne è precisa testimonianza."[150]

References

[edit]- ^ Camedda, Marco (2012). "Un viaggio di tremila anni per scoprire Sos zigantes". La Nuova Sardegna (in Italian). Sassari. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ Keys, David (17 February 2012). "Prehistoric cybermen? Sardinia's lost warriors rise from the dust". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Nardi, Roberto (2008). "Monte Prama, Sardinia, Italy". Conservation for Presentation: A key for protecting monuments. Studies in Conservation. Vol. 53. Centro di Conservazione Archeologica (CCA-Roma.org). pp. 3–4. doi:10.1179/sic.2008.53.Supplement-1.22. S2CID 162297653.

- ^ a b c d Nardi, Roberto (2011). "The Statues". Documentation Conservation. Restoration and Museum Display. Translated by Rockwell, Cynthia (English translation). Rome: Centro di Conservazione Archeologica (CCA). Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Meloni, Antonio (2011). "Giganti di Mont'e Prama verso Cabras e Cagliari". La Nuova Sardegna (in Italian). Sassari. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012.

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (2006), pp. 84–86.

- ^ Andreoli, Alice (2007). L'armata sarda dei Giganti di pietra (Report). Il Venerdì di Repubblica, July 27, 2007. Rome: Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso. pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Leonelli, Valentina (2012). "Restauri Mont'e Prama, il mistero dei giganti". Archeo. Attualità del Passato (in Italian): 26–28. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Ridgway, David (1979–1980). "Archaeology in Sardinia and Etruria (1974–1979)". Archaeological Reports. 26: 54–70. doi:10.2307/581176. JSTOR 581176. S2CID 129097614. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Basile, Joseph J. (2004). "Comparanda for the Capestrano warrior". The Capestrano Warrior and Related Monuments of the Seventh to Fifth Centuries B.C. p. 22. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2017 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ a b Atzeni, Enrico (2004). Laconi the Menhir Museum (PDF). Sassari: Delfino. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 27 October 2012. [permanent dead link]

- ^ Mussi, Margherita (2009). "The Venus of Macomer: A little-known prehistoric figurine from Sardinia". In Bahn, Paul G. (ed.). An Enquiring Mind: Essays in honor of Alexander Marshack (PDF). American School of Prehistoric Research. Harvard University. pp. 193–210. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022 – via academia.edu.

with images

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (1999), pp. 9–11.

- ^ Foschi Nieddu, Alba (2000). "La veneretta di Macomer". Nuoro Oggi (in Italian). Nuoro. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Mussi, Margherita (2010). "The Venus of Macomer: A little-known prehistoric figurine from Sardinia". In Bahn, Paul G. (ed.). An Enquiring Mind: Studies in Honor of Alexander Marshack. Oxbow Books. p. 207. ISBN 978-1842173831. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (1999), p. 21.

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (1966), p. 71.

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (1999), pp. 36–62.

- ^ Contu, Ercole (2000). The Prehistoric Altar of Monte d'Accoddi (PDF). Sassari: Delfino. p. 58. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2012.

- ^ Quoted by Tanda (1984), p. 147, Figure 35.

- ^ Antona, Angela (2005). Il complesso nuragico di Lu Brandali e i monumenti archeologici di Santa Teresa di Gallura (PDF) (in Italian). Sassari: Delfino. p. 19. ISBN 88-7138-384-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Giovanni Ugas, L'alba dei Nuraghi, p. 196. Fabula Ed, Cagliari, 2005

- ^ a b De Lanfranchi, François (2002). "Mégalithisme et façonnage des roches destinées à être plantées. Concepts, terminologie et chronologie". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French): 331–356.

- ^ Michel-Claude Weiss, Les Statues-menhirs de la Corse et le contexte méditerranéen,1997.

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (2008), p. 1723.

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (1982), p. 98.

- ^ Quoted by Lilliu (1995), pp. 421–507.

- ^ Tore, Giovanni (1978). "Su alcune stele funerarie sarde di età punico-romana". Latomus (in Italian). XXXIV (2). Société d'Études Latines de Bruxelles: 315–316, Figure XIII-4 (On the text is wrongly shown Figure XIII–3). JSTOR 41533249.