White supremacy

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them.[1] The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine of scientific racism and was a key justification for European colonialism.[2][3]

As a political ideology, it imposes and maintains cultural, social, political, historical or institutional domination by white people and non-white supporters. In the past, this ideology had been put into effect through socioeconomic and legal structures such as the Atlantic slave trade, European colonial labor and social practices, the Scramble for Africa, Jim Crow laws in the United States, the activities of the Native Land Court in New Zealand,[4] the White Australia policies from the 1890s to the mid-1970s, and apartheid in South Africa.[5][6] This ideology is also today present among neo-Confederates.

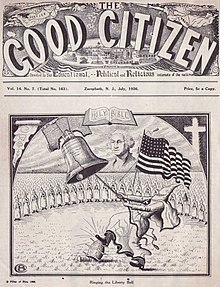

White supremacy underlies a spectrum of contemporary movements including white nationalism, white separatism, neo-Nazism, and the Christian Identity movement.[7] In the United States, white supremacy is primarily associated with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), Aryan Nations, and the White American Resistance movement, all of which are also considered to be antisemitic.[8] The Proud Boys, despite claiming non-association with white supremacy, have been described in academic contexts as being such.[9] In recent years, websites such as Twitter (known as X since July 2023), Reddit, and Stormfront, and the first campaign and presidency of Donald Trump, have contributed to an increased activity and interest in white supremacy.[10][11][12][13][14]

Different forms of white supremacy have different conceptions of who is considered white (though the exemplar is generally light-skinned, blond-haired, and blue-eyed — traits most common in northern Europe and that are viewed pseudoscientifically as being traits of an Aryan race), and not all white-supremacist organizations agree on who is their greatest enemy.[15] Different groups of white supremacists identify various racial, ethnic, religious, and other enemies,[15] most commonly those of Sub-Saharan African ancestry, Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Oceania, Asians, multiracial people, Middle Eastern people, Jews,[16][17][18] Muslims, and LGBTQ+ people.[19][20][21][22]

In academic usage, particularly in critical race theory or intersectionality, "white supremacy" can also refer to a social system in which white people enjoy structural advantages (privilege) over other ethnic groups, on both a collective and individual level, despite formal legal equality.[23][24][25][26][27]

History

White supremacy has ideological foundations that date back to 17th-century scientific racism, the predominant paradigm of human variation that helped shape international relations and racial policy from the latter part of the Age of Enlightenment until the late 20th century (marked by decolonization and the abolition of apartheid in South Africa in 1991, followed by that country's first multiracial elections in 1994).[citation needed]

United States

Early history

White supremacy was dominant in the United States both before and after the American Civil War, and it persisted for decades after the Reconstruction Era.[29] Prior to the Civil War, many wealthy white Americans owned slaves; they tried to justify their economic exploitation of black people by creating a "scientific" theory of white superiority and black inferiority.[30] One such slave owner, future president Thomas Jefferson, wrote in 1785 that blacks were "inferior to the whites in the endowments of body and mind."[31] In the antebellum South, four million slaves were denied freedom.[32] The outbreak of the Civil War saw the desire to uphold white supremacy being cited as a cause for state secession[33] and the formation of the Confederate States of America.[34] In an 1890 editorial about Native Americans and the American Indian Wars, author L. Frank Baum wrote: "The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians."[35]

The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to whites only.[36] In some parts of the United States, many people who were considered non-white were disenfranchised, barred from government office, and prevented from holding most government jobs well into the second half of the 20th century. Professor Leland T. Saito of the University of Southern California writes: "Throughout the history of the United States, race has been used by whites for legitimizing and creating difference and social, economic and political exclusion."[37]

20th century

The denial of social and political freedom to minorities continued into the mid-20th century, resulting in the civil rights movement.[38] The movement was spurred by the lynching of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy. David Jackson writes it was the image of the "murdered child's ravaged body, that forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism."[39] Vann R. Newkirk II wrote "the trial of his killers became a pageant illuminating the tyranny of white supremacy."[40] Moved by the image of Till's body in the casket, one hundred days after his murder Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white person.[41]

Sociologist Stephen Klineberg has stated that U.S. immigration laws prior to 1965 clearly "declared that Northern Europeans are a superior subspecies of the white race".[42][a] The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened entry to the U.S. to non-Germanic groups, and significantly altered the demographic mix in the U.S. as a result.[42] With 38 U.S. states having banned interracial marriage through anti-miscegenation laws, the last 16 states had such laws in place until 1967 when they were invalidated by the Supreme Court of the United States' decision in Loving v. Virginia.[43] These mid-century gains had a major impact on white Americans' political views; segregation and white racial superiority, which had been publicly endorsed in the 1940s, became minority views within the white community by the mid-1970s, and continued to decline in 1990s' polls to a single-digit percentage.[44][45] For sociologist Howard Winant, these shifts marked the end of "monolithic white supremacy" in the United States.[46]

After the mid-1960s, white supremacy remained an important ideology to the American far-right.[47] According to Kathleen Belew, a historian of race and racism in the United States, white militancy shifted after the Vietnam War from supporting the existing racial order to a more radical position (self-described as "white power" or "white nationalism") committed to overthrowing the United States government and establishing a white homeland.[48][49] Such anti-government militia organizations are one of three major strands of violent right-wing movements in the United States, with white-supremacist groups (such as the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazi organizations, and racist skinheads) and a religious fundamentalist movement (such as Christian Identity) being the other two.[50][51] Howard Winant writes that, "On the far right the cornerstone of white identity is belief in an ineluctable, unalterable racialized difference between whites and nonwhites."[52] In the view of philosopher Jason Stanley, white supremacy in the United States is an example of the fascist politics of hierarchy, in that it "demands and implies a perpetual hierarchy" in which whites dominate and control non-whites.[53]

21st century

The presidential campaign of Donald Trump led to a surge of interest in white supremacy and white nationalism in the United States, bringing increased media attention and new members to their movement; his campaign enjoyed their widespread support.[11][12][13][14]

Some academics argue that outcomes from the 2016 United States Presidential Election reflect ongoing challenges with white supremacy.[54][55] Psychologist Janet Helms suggested that the normalizing behaviors of social institutions of education, government, and healthcare are organized around the "birthright of...the power to control society's resources and determine the rules for [those resources]".[6] Educators, literary theorists, and other political experts have raised similar questions, connecting the scapegoating of disenfranchised populations to white superiority.[56][57]

As of 2018, there were over 600 white-supremacist organizations recorded in the U.S.[58] On July 23, 2019, Christopher A. Wray, the head of the FBI, said at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that the agency had made around 100 domestic terrorism arrests since October 1, 2018, and that the majority of them were connected in some way with white supremacy. Wray said that the Bureau was "aggressively pursuing [domestic terrorism] using both counterterrorism resources and criminal investigative resources and partnering closely with our state and local partners," but said that it was focused on the violence itself and not on its ideological basis. A similar number of arrests had been made for instances of international terrorism. In the past, Wray has said that white supremacy was a significant and "pervasive" threat to the U.S.[59]

On September 20, 2019, the acting Secretary of Homeland Security, Kevin McAleenan, announced his department's revised strategy for counter-terrorism, which included a new emphasis on the dangers inherent in the white-supremacy movement. McAleenan called white supremacy one of the most "potent ideologies" behind domestic terrorism-related violent acts. In a speech at the Brookings Institution, McAleenan cited a series of high-profile shooting incidents, and said "In our modern age, the continued menace of racially based violent extremism, particularly white supremacist extremism, is an abhorrent affront to the nation, the struggle and unity of its diverse population." The new strategy will include better tracking and analysis of threats, sharing information with local officials, training local law enforcement on how to deal with shooting events, discouraging the hosting of hate sites online, and encouraging counter-messages.[60][61]

In a 2020 article in The New York Times titled "How White Women Use Themselves as Instruments of Terror", columnist Charles M. Blow wrote:[62]

We often like to make white supremacy a testosterone-fueled masculine expression, but it is just as likely to wear heels as a hood. Indeed, untold numbers of lynchings were executed because white women had claimed that a black man raped, assaulted, talked to or glanced at them. The Tulsa race massacre, the destruction of Black Wall Street, was spurred by an incident between a white female elevator operator and a black man. As the Oklahoma Historical Society points out, the most common explanation is that he stepped on her toe. As many as 300 people were killed because of it. The torture and murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955, a lynching actually, occurred because a white woman said that he "grabbed her and was menacing and sexually crude toward her". This practice, this exercise in racial extremism has been dragged into the modern era through the weaponizing of 9-1-1, often by white women, to invoke the power and force of the police who they are fully aware are hostile to black men. This was again evident when a white woman in New York's Central Park told a black man, a bird-watcher, that she was going to call the police and tell them that he was threatening her life.

Patterns of influence

Political violence

The Tuskegee Institute has estimated that 3,446 blacks were the victims of lynchings in the United States between 1882 and 1968, with the peak occurring in the 1890s at a time of economic stress in the South and increasing political suppression of blacks. If 1,297 whites were also lynched during this period, blacks were disproportionally targeted, representing 72.7% of all people lynched.[63][64] According to scholar Amy L. Wood, "lynching photographs constructed and perpetuated white supremacist ideology by creating permanent images of a controlled white citizenry juxtaposed to images of helpless and powerless black men."[65]

School curriculum

White supremacy has also played a part in U.S. school curriculum. Over the course of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, material across the spectrum of academic disciplines has been taught with a heavy emphasis on white culture, contributions, and experiences, and a lack of representation of non-white groups' perspectives and accomplishments.[66][67][68][69] In the 19th century, Geography lessons contained teachings on a fixed racial hierarchy, which white people topped.[70] Mills (1994) writes that history as it is taught is really the history of white people, and it is taught in a way that favors white Americans and white people in general. He states that the language used to tell history minimizes the violent acts committed by white people over the centuries, citing the use of the words, for example, "discovery," "colonization," and "New World" when describing what was ultimately a European conquest of the Western Hemisphere and its indigenous peoples.[67] Swartz (1992) seconds this reading of modern history narratives when it comes to the experiences, resistances, and accomplishments of black Americans throughout the Middle Passage, slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the civil rights movement. In an analysis of American history textbooks, she highlights word choices that repetitively "normalize" slavery and the inhumane treatment of black people. She also notes the frequent showcasing of white abolitionists and actual exclusion of black abolitionists and the fact that black Americans had been mobilizing for abolition for centuries before the major white American push for abolition in the 19th century. She ultimately asserts the presence of a masternarrative that centers Europe and its associated peoples (white people) in school curriculum, particularly as it pertains to history.[71] She writes that this masternarrative condenses history into only history that is relevant to, and to some extent beneficial for, white Americans.[71]

Elson (1964) provides detailed information about the historic dissemination of simplistic and negative ideas about non-white races.[67][72][73] Native Americans, who were subjected to attempts of cultural genocide by the U.S. government through the use of American Indian boarding schools,[72][74] were characterized as homogenously "cruel," a violent menace toward white Americans, and lacking civilization or societal complexity (p. 74).[70] For example, in the 19th century, black Americans were consistently portrayed as lazy, immature, and intellectually and morally inferior to white Americans, and in many ways not deserving of equal participation in U.S. society.[68][72][70] For example, a math problem in a 19th-century textbook read, "If 5 white men can do as much work as 7 negroes..." implying that white men are more industrious and competent than black men (p. 99).[75] In addition, little to nothing was taught about black Americans' contributions, or their histories before being brought to U.S. soil as slaves.[72][73] According to Wayne (1972), this approach was taken especially much after the Civil War to maintain whites' hegemony over emancipated black Americans.[72] Other racial groups have received oppressive treatment, including Mexican Americans, who temporarily were prevented from learning the same curriculum as white Americans because they supposedly were intellectually inferior, and Asian Americans, some of whom were prevented from learning much about their ancestral lands because they were deemed a threat to "American" culture, i.e. white culture, at the turn of the 20th century.[72]

Role of the internet

With the emergence of Twitter in 2006, and platforms such as Stormfront, which was launched in 1996, an alt-right portal for white supremacists with similar beliefs, both adults and children, was provided in which they were given a way to connect. Jessie Daniels, of CUNY-Hunter College, discussed the emergence of other social media outlets such as 4chan and Reddit, which meant that the "spread of white nationalist symbols and ideas could be accelerated and amplified."[10] Sociologist Kathleen Blee notes that the anonymity which the Internet provides can make it difficult to track the extent of white-supremacist activity in the country, but nevertheless she and other experts[76] see an increase in the number of hate crimes and amount of white-supremacist violence. In the latest wave of white supremacy, in the age of the Internet, Blee sees the movement as having become primarily a virtual one, in which divisions between groups become blurred: "[A]ll these various groups that get jumbled together as the alt-right and people who have come in from the more traditional neo-Nazi world. We're in a very different world now."[77]

David Duke, a former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, wrote in 1999 that the Internet was going to create a "chain reaction of racial enlightenment that will shake the world."[78] Daniels documents that racist groups see the Internet as a way to spread their ideologies, influence others and gain supporters.[10] Legal scholar Richard Hasen describes a "dark side" of social media:

There certainly were hate groups before the Internet and social media. [But with social media] it just becomes easier to organize, to spread the word, for people to know where to go. It could be to raise money, or it could be to engage in attacks on social media. Some of the activity is virtual. Some of it is in a physical place. Social media has lowered the collective-action problems that individuals who might want to be in a hate group would face. You can see that there are people out there like you. That's the dark side of social media.[79]

A series on YouTube hosted by the grandson of Thomas Robb, the national director of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, "presents the Klan's ideology in a format aimed at kids — more specifically, white kids."[80] The short episodes inveigh against race-mixing, and extol other white-supremacist ideologies. A short documentary published by TRT describes Imran Garda's experience, a journalist of Indian descent, who met with Thomas Robb and a traditional KKK group. A sign that greets people who enter the town states "Diversity is a code for white genocide." The KKK group interviewed in the documentary summarizes its ideals, principles, and beliefs, which are emblematic of white supremacists in the United States. The comic book super hero Captain America was used for dog whistle politics by the alt-right in college campus recruitment in 2017, an ironic co-optation because Captain America battled against Nazis in the comics, and was created by Jewish cartoonists.[81][82]

British Commonwealth

There has been debate whether Winston Churchill, who was voted "the greatest ever Briton" in 2002, was "a racist and white supremacist".[83] In the context of rejecting the Arab wish to stop Jewish immigration to Palestine, he said:

I do not admit that the dog in the manger has the final right to the manger, though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit for instance that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to those people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race or at any rate a more worldly-wise race ... has come in and taken their place."[84]

British historian Richard Toye, author of Churchill's Empire, concluded that "Churchill did think that white people were superior."[83]

South Africa

A number of Southern African nations experienced severe racial tension and conflict during global decolonization, particularly as white Africans of European ancestry fought to protect their preferential social and political status. Racial segregation in South Africa began in colonial times under the Dutch Empire. It continued when the British took over the Cape of Good Hope in 1795. Apartheid was introduced as an officially structured policy by the Afrikaner-dominated National Party after the general election of 1948. Apartheid's legislation divided inhabitants into four racial groups — "black", "white", "coloured", and "Indian", with coloured divided into several sub-classifications.[85] In 1970, the Afrikaner-run government abolished non-white political representation, and starting that year black people were deprived of South African citizenship.[86] South Africa abolished apartheid in 1991.[87][88]

Rhodesia

In Rhodesia a predominantly white government issued its own unilateral declaration of independence from the United Kingdom in 1965 during an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to avoid majority rule.[89] Following the Rhodesian Bush War which was fought by African nationalists, Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith acceded to biracial political representation in 1978 and the state achieved recognition from the United Kingdom as Zimbabwe in 1980.[90]

Germany

Nazism promoted the idea of a superior Germanic people or Aryan race in Germany during the early 20th century. Notions of white supremacy and Aryan racial superiority were combined in the 19th century, with white supremacists maintaining the belief that white people were members of an Aryan "master race" that was superior to other races, particularly the Jews, who were described as the "Semitic race", Slavs, and Gypsies, who they associated with "cultural sterility". Arthur de Gobineau, a French racial theorist and aristocrat, blamed the fall of the ancien régime in France on racial degeneracy caused by racial intermixing, which he argued had destroyed the "purity" of the Nordic or Germanic race. Gobineau's theories, which attracted a strong following in Germany, emphasized the existence of an irreconcilable polarity between Aryan or Germanic peoples and Jewish culture.[91]

As the Nazi Party's chief racial theorist, Alfred Rosenberg oversaw the construction of a human racial "ladder" that justified Hitler's racial and ethnic policies. Rosenberg promoted the Nordic theory, which regarded Nordics as the "master race", superior to all others, including other Aryans (Indo-Europeans).[92] Rosenberg got the racial term Untermensch from the title of Klansman Lothrop Stoddard's 1922 book The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under-man.[93] It was later adopted by the Nazis from that book's German version Der Kulturumsturz: Die Drohung des Untermenschen (1925).[94] Rosenberg was the leading Nazi who attributed the concept of the East-European "under man" to Stoddard.[95] An advocate of the U.S. immigration laws that favored Northern Europeans, Stoddard wrote primarily on the alleged dangers posed by "colored" peoples to white civilization, and wrote The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy in 1920. In establishing a restrictive entry system for Germany in 1925, Hitler wrote of his admiration for America's immigration laws: "The American Union categorically refuses the immigration of physically unhealthy elements, and simply excludes the immigration of certain races."[96]

German praise for America's institutional racism, previously found in Hitler's Mein Kampf, was continuous throughout the early 1930s. Nazi lawyers were advocates of the use of American models.[97] Race-based U.S. citizenship and anti-miscegenation laws directly inspired the Nazis' two principal Nuremberg racial laws—the Citizenship Law and the Blood Law.[97] To preserve the Aryan or Nordic race, the Nazis introduced the Nuremberg Laws in 1935, which forbade sexual relations and marriages between Germans and Jews, and later between Germans and Romani and Slavs. The Nazis used the Mendelian inheritance theory to argue that social traits were innate, claiming that there was a racial nature associated with certain general traits, such as inventiveness or criminal behavior.[98]

According to the 2012 annual report of Germany's interior intelligence service, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, at the time there were 26,000 right-wing extremists living in Germany, including 6,000 neo-Nazis.[99]

Australia and New Zealand

Fifty-one people died from two consecutive terrorist attacks at the Al Noor Mosque and the Linwood Islamic Centre by an Australian white supremacist carried out on March 15, 2019. The terrorist attacks have been described by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern as "One of New Zealand's darkest days". On August 27, 2020, the shooter was sentenced to life without parole.[100][101][102]

In 2016, there was a rise in debate over the appropriateness of the naming of Massey University in Palmerston North after William Massey, whom many historians and critics have described as a white supremacist.[103] Lecturer Steve Elers was a leading proponent of the idea that Massey was an avowed white supremacist, given Massey "made several anti-Chinese racist statements in the public domain" and intensified the New Zealand head tax.[104][105] In 1921, Massey wrote in the Evening Post: "New Zealanders are probably the purest Anglo-Saxon population in the British Empire. Nature intended New Zealand to be a white man's country, and it must be kept as such. The strain of Polynesian will be no detriment". This is one of many quotes attributed to him regarded as being openly racist.[106]

Ideologies and movements

Supporters of Nordicism consider the "Nordic peoples" to be a superior race.[107] By the early 19th century, white supremacy was attached to emerging theories of racial hierarchy. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer attributed cultural primacy to the white race:

The highest civilization and culture, apart from the ancient Hindus and Egyptians, are found exclusively among the white races; and even with many dark peoples, the ruling caste or race is fairer in colour than the rest and has, therefore, evidently immigrated, for example, the Brahmins, the Incas, and the rulers of the South Sea Islands. All this is due to the fact that necessity is the mother of invention because those tribes that emigrated early to the north, and there gradually became white, had to develop all their intellectual powers and invent and perfect all the arts in their struggle with need, want and misery, which in their many forms were brought about by the climate.[108]

The eugenicist Madison Grant argued in his 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, that the Nordic race had been responsible for most of humanity's great achievements, and that admixture was "race suicide".[109] In this book, Europeans who are not of Germanic origin but have Nordic characteristics such as blonde/red hair and blue/green/gray eyes, were considered to be a Nordic admixture and suitable for Aryanization.[110]

In the United States, the groups most associated with the white-supremacist movement are the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), Aryan Nations, and the White American Resistance movement, all of which are also considered to be antisemitic. The Proud Boys, despite claiming non-association with white supremacy, have been described in academic contexts as being such.[9] Many white-supremacist groups are based on the concept of preserving genetic purity, and do not focus solely on discrimination based on skin color. The KKK's reasons for supporting racial segregation are not primarily based on religious ideals, but some Klan groups are openly Protestant.[citation needed] The 1915 silent drama film The Birth of a Nation followed the rising racial, economic, political, and geographic tensions leading up to the Emancipation Proclamation and the Southern Reconstruction era that was the genesis of the Ku Klux Klan.[111]

Nazi Germany promulgated white supremacy based on the belief that the Aryan race, or the Germans, were the master race. It was combined with a eugenics programme that aimed for racial hygiene through compulsory sterilization of sick individuals and extermination of Untermenschen ("subhumans"): Slavs, Jews and Romani, which eventually culminated in the Holocaust.[112][113][114][115][116]

Christian Identity is another movement closely tied to white supremacy. Some white supremacists identify themselves as Odinists, although many Odinists reject white supremacy. Some white-supremacist groups, such as the South African Boeremag, conflate elements of Christianity and Odinism. Creativity (formerly known as "The World Church of the Creator") is atheistic and it denounces Christianity and other theistic religions.[117][118] Aside from this, its ideology is similar to that of many Christian Identity groups because it believes in the antisemitic conspiracy theory that there is a "Jewish conspiracy" in control of governments, the banking industry and the media. Matthew F. Hale, founder of the World Church of the Creator, has published articles stating that all races other than white are "mud races", which is what the group's religion teaches.[citation needed]

The white-supremacist ideology has become associated with a racist faction of the skinhead subculture, despite the fact that when the skinhead culture first developed in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s, it was heavily influenced by black fashions and music, especially Jamaican reggae and ska, and African American soul music.[119][120][121]

White-supremacist recruitment activities are primarily conducted at a grassroots level as well as on the Internet. Widespread access to the Internet has led to a dramatic increase in white-supremacist websites.[122] The Internet provides a venue for open expression of white-supremacist ideas at little social cost because people who post the information are able to remain anonymous.

White nationalism

White separatism

White separatism is a political and social movement that seeks the separation of white people from people of other races and ethnicities. This may include the establishment of a white ethnostate by removing non-whites from existing communities or by forming new communities elsewhere.[123]

Most modern researchers do not view white separatism as distinct from white-supremacist beliefs. The Anti-Defamation League defines white separatism as "a form of white supremacy";[124] the Southern Poverty Law Center defines both white nationalism and white separatism as "ideologies based on white supremacy."[125] Facebook has banned content that is openly white nationalist or white separatist because "white nationalism and white separatism cannot be meaningfully separated from white supremacy and organized hate groups".[126][127]

Use of the term to self-identify has been criticized as a dishonest rhetorical ploy. The Anti-Defamation League argues that white supremacists use the phrase because they believe it has fewer negative connotations than the term white supremacist.[128]

Dobratz and Shanks-Meile reported that adherents usually reject marriage "outside the white race". They argued for the existence of "a distinction between the white supremacist's desire to dominate (as in apartheid, slavery, or segregation) and complete separation by race".[129] They argued that this is a matter of pragmatism, because, while many white supremacists are also white separatists, contemporary white separatists reject the view that returning to a system of segregation is possible or desirable in the United States.[130]

Notable white separatists

- Andrew Anglin

- Virginia Abernethy

- Fraser Anning

- Gordon Lee Baum

- Louis Beam

- Don Black

- Richard Girnt Butler

- Thomas W. Chittum

- Harold Covington

- David Duke

- Mike Enoch

- Samuel T. Francis

- Nick Griffin

- Michael H. Hart

- Arthur Kemp

- Ben Klassen

- David Lane

- William Massey

- Robert Jay Mathews

- Tom Metzger

- Merlin Miller

- Revilo P. Oliver

- William Luther Pierce

- Richard B. Spencer

- Kevin Alfred Strom

- Jared Taylor

- Eugène Terre'Blanche

- Andries Treurnicht

- John Tyndall

- Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd

- Varg Vikernes

Aligned organizations and philosophies

- Aryan Brotherhood

- Christian Identity

- Council of Conservative Citizens

- Ethnopluralism

- Eurocentrism

- Ku Klux Klan

- National-anarchism

- Neo-Confederate

- New Orleans Protocol

- Northwest Territorial Imperative

- Volkstaat

- White pride

Academic use of the term

The term white supremacy is used in some academic studies of racial power to denote a system of structural or societal racism which privileges white people over others, regardless of the presence or the absence of racial hatred. According to this definition, white racial advantages occur at both a collective and an individual level (ceteris paribus, i. e., when individuals are compared that do not differ relevantly except in ethnicity). Legal scholar Frances Lee Ansley explains this definition as follows:

By "white supremacy" I do not mean to allude only to the self-conscious racism of white supremacist hate groups. I refer instead to a political, economic and cultural system in which whites overwhelmingly control power and material resources, conscious and unconscious ideas of white superiority and entitlement are widespread, and relations of white dominance and non-white subordination are daily reenacted across a broad array of institutions and social settings.[23][24]

This and similar definitions have been adopted or proposed by Charles W. Mills,[25] bell hooks,[26] David Gillborn,[27] Jessie Daniels,[131] and Neely Fuller Jr,[132] and they are widely used in critical race theory and intersectional feminism. Some anti-racist educators, such as Betita Martinez and the Challenging White Supremacy workshop, also use the term in this way. The term expresses historic continuities between a pre–civil rights movement era of open white supremacy and the current racial power structure of the United States. It also expresses the visceral impact of structural racism through "provocative and brutal" language that characterizes racism as "nefarious, global, systemic, and constant".[133] Academic users of the term sometimes prefer it to racism because it allows for a distinction to be drawn between racist feelings and white racial advantage or privilege.[134][135][14] John McWhorter, a specialist in language and race relations, explains the gradual replacement of "racism" by "white supremacy" by the fact that "potent terms need refreshment, especially when heavily used", drawing a parallel with the replacement of "chauvinist" by "sexist"[136].

Other intellectuals have criticized the term's recent rise in popularity among leftist activists as counterproductive. John McWhorter has described the use of "white supremacy" as straying from its commonly accepted meaning to encompass less extreme issues, thereby cheapening the term and potentially derailing productive discussion.[137][138] Political columnist Kevin Drum attributes the term's growing popularity to frequent use by Ta-Nehisi Coates, describing it as a "terrible fad" that fails to convey nuance. He claims that the term should be reserved for those who are trying to promote the idea that whites are inherently superior to blacks and not used to characterize less blatantly racist beliefs or actions.[139][140] The academic use of the term to refer to systemic racism has been criticized by Conor Friedersdorf for the confusion that it creates for the general public, inasmuch as it differs from the more common dictionary definition; he argues that it is likely to alienate those that it hopes to convince.[140]

See also

- Afrophobia – Fear or hatred of African people

- Anti-Mexican sentiment – Prejudice against Mexico

- Anti-Romani sentiment – Racism against Romani people

- Antisemitism – Hostility, prejudice, or discrimination against Jews

- Basking in reflected glory – associating oneself with successful other such that their success becomes one's own

- Black supremacy – Belief in superiority of black people

- Boreal (politics and culture) – Form of exoticism

- Christian Identity – White supremacist interpretation of Christianity

- Creativity (religion) – Religion classified as a neo-Nazi hate group

- Eurocentrism

- Frances Cress Welsing – American psychiatrist (1935–2016)

- Heroes of the Fiery Cross – 1928 nonfiction book by white supremacist Alma Bridwell White

- Kinism – Segregationist religious movement

- Me and White Supremacy – 2020 book by Layla Saad

- Race and intelligence – Discussions and claims of differences in intelligence along racial lines

- Racism against Black Americans

- "The White Man's Burden – Poem by the English poet Rudyard Kipling"

- Western Supremacy (book) – Book article

- White nationalist organizations

- White power skinheads – Members of a neo-Nazi, white supremacist and antisemitic offshoot of the skinhead subculture

- White power symbol (disambiguation)

- White pride – Racial expression

- White nationalism – Ideology that seeks to develop a white national identity

Notes

- ^ This quote is by Klineberg in the NPR story, not from the text of any US law.

References

- ^ John Philip Jenkins (April 13, 2021). "white supremacy". britannica. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ American Association of Physical Anthropologists (March 27, 2019). "AAPA Statement on Race and Racism". American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

Instead, the Western concept of race must be understood as a classification system that emerged from, and in support of, European colonialism, oppression, and discrimination.

- ^ "Ostensibly scientific": cf. Theodore M. Porter, Dorothy Ross (eds.) 2003. The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 7, The Modern Social Sciences Cambridge University Press, p. 293 "Race has long played a powerful popular role in explaining social and cultural traits, often in ostensibly scientific terms"; Adam Kuper, Jessica Kuper (eds.), The Social Science Encyclopedia (1996), "Racism", p. 716: "This [sc. scientific] racism entailed the use of 'scientific techniques', to sanction the belief in European and American racial Superiority"; Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Questions to Sociobiology (1998), "Race, theories of", p. 18: "Its exponents [sc. of scientific racism] tended to equate race with species and claimed that it constituted a scientific explanation of human history"; Terry Jay Ellingson, The myth of the noble savage (2001), 147ff. "In scientific racism, the racism was never very scientific; nor, it could at least be argued, was whatever met the qualifications of actual science ever very racist" (p. 151); Paul A. Erickson, Liam D. Murphy, A History of Anthropological Theory (2008), p. 152: "Scientific racism: Improper or incorrect science that actively or passively supports racism".

- ^ Ray, William (June 3, 2022). "Season 2 Ep 6: Native Land Court". RNZ. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Wildman, Stephanie M. (1996). Privilege Revealed: How Invisible Preference Undermines America. NYU Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8147-9303-9.

- ^ a b Helms, Janet (2016). "An election to save White Heterosexual Male Privilege" (PDF). Latina/o Psychology Today. 3 (2): 6–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2017.

- ^ Brody, Richard (April 9, 2021). ""Exterminate All the Brutes," Reviewed: A Vast, Agonizing History of White Supremacy". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ Building a Corporate Culture of Security: Strategies for Strengthening Organizational Resiliency. p. 41.

- ^ a b Kutner, Samantha (2020). "Swiping Right: The Allure of Hyper Masculinity and Cryptofascism for Men Who Join the Proud Boys" (PDF). International Centre for Counter-Terrorism: 1. JSTOR resrep25259. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 19, 2023. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c Daniel, Jessie (October 19, 2017). "Twitter and White Supremacy: A Love Story". CUNY Academic Works. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ a b "Why White-Nationalist Thugs Thrill to Trump". National Review. April 11, 2016. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Smith, Candace. "The White Nationalists Who Support Donald Trump". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ a b "How Trump Is Inspiring A New Generation Of White Nationalists". HuffPost. March 7, 2016. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Pollock, Nicolas; Myszkowski, Sophia. "Hate Groups Are Growing Under Trump". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 21, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Flint, Colin (2004). Spaces of Hate: Geographies of Discrimination and Intolerance in the U.S.A. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-415-93586-9.

Although white racist activists must adopt a political identity of whiteness, the flimsy definition of whiteness in modern culture poses special challenges for them. In both mainstream and white supremacist discourse, to be white is to be distinct from those marked as nonwhite, yet the placement of the distinguishing line has varied significantly in different times and places.

- ^ "'Jews will not replace us': Why white supremacists go after Jews". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ "How Anti-Semitism Is Tied To White Nationalism". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ Ali, Wajahat (January 19, 2022). "Antisemitism Is Driving White Supremacist Terror In The United States". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "Why Are So Many White Nationalists 'Virulently Anti-LGBT'?". National Broadcasting Company. August 21, 2017. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ "Why are white nationalist groups targeting LGBTQ groups?". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "White supremacy's rigid views on gender and sexuality". Cable News Network. June 15, 2022. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "Knoxville Pridefest parade: White nationalists to protest". Knoxnews. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Ansley, Frances Lee (1989). "Stirring the Ashes: Race, Class and the Future of Civil Rights Scholarship". Cornell Law Review. 74: 993ff.

- ^ a b Ansley, Frances Lee (June 29, 1997). "White supremacy (and what we should do about it)". In Richard Delgado; Jean Stefancic (eds.). Critical white studies: Looking behind the mirror. Temple University Press. p. 592. ISBN 978-1-56639-532-8.

- ^ a b Mills, C.W. (2003). "White supremacy as sociopolitical system: A philosophical perspective". White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism: 35–48.

- ^ a b Hooks, Bell (2000). Feminist theory: From margin to center. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-1663-5.

- ^ a b Gillborn, David (September 1, 2006). "Rethinking White Supremacy Who Counts in 'WhiteWorld'". Ethnicities. 6 (3): 318–40. doi:10.1177/1468796806068323. ISSN 1468-7968. S2CID 8984059. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "History of Lynching in America". NAACP. Archived from the original on January 3, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Fredrickson, George (1981). White Supremacy. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-19-503042-6.

- ^ Boggs, James (October 1970). "Uprooting Racism and Racists in the United States". The Black Scholar. 2 (2). Paradigm Publishers: 2–5. doi:10.1080/00064246.1970.11431000. JSTOR 41202851.

- ^ Paul Finkelman (November 12, 2012). "The Monster of Monticello" Archived April 9, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Harris, Paul (June 16, 2012). "How the end of slavery led to starvation and death for millions of black Americans". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine: "We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable. That in this free government all white men are and of right ought to be entitled to equal civil and political rights; that the servitude of the African race, as existing in these States, is mutually beneficial to both bond and free, and is abundantly authorized and justified by the experience of mankind, and the revealed will of the Almighty Creator, as recognized by all Christian nations; while the destruction of the existing relations between the two races, as advocated by our sectional enemies, would bring inevitable calamities upon both and desolation upon the fifteen slave-holding states."

- ^ The controversial "Cornerstone Speech", Alexander H. Stephens (Vice President of the Confederate States), March 21, 1861, Savannah, Georgia Archived November 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine: "Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition."

- ^ "L. Frank Baum's Editorials on the Sioux Nation". Archived from the original on December 9, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2007. Full text of both, with commentary by professor A. Waller Hastings

- ^ Schultz, Jeffrey D. (2002). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: African Americans and Asian Americans. Oryx Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-57356-148-8. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ Leland T. Saito (1998). "Race and Politics: Asian Americans, Latinos, and Whites in a Los Angeles Suburb". p. 154. University of Illinois Press

- ^ "50th Anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Panel Discussion at the Black Archives of Mid-America" (Press release). The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. August 7, 2013. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ "How The Horrific Photograph Of Emmett Till Helped Energize The Civil Rights Movement". 100 Photographs | The Most Influential Images of All Time. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ Newkirk, Vann R. II. "How 'The Blood of Emmett Till' Still Stains America Today". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ Haas, Jeffrey (2011). The Assassination of Fred Hampton. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-56976-709-2.

- ^ a b Jennifer Ludden. "1965 immigration law changed face of America". All Things Considered. NPR. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ Warren, Earl. Majority opinion. Loving v. Virginia. Documents of American Constitutional and Legal History, edited by Urofsky and Finkelman, Oxford UP, 2002, p. 779.

- ^ Schuman, Howard; Steeh, Charlotte; Bobo, Lawrence; Krysan, Maria (1997). Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations. Harvard University Press. pp. 103ff. ISBN 978-0-674-74568-1.

The questions deal with most of the major racial issues that became focal in the middle of the twentieth century: integration of public accommodations, school integration, residential integration, and job discrimination [and] racial intermarriage and willingness to vote for a black presidential candidate. ... The trends that occur for most of the principle items are quite similar and can be illustrated ...using attitudes toward school integration as an example. The figure shows that there has been a massive and continuous movement of the American public from overwhelming acceptance of the principle of segregated schooling in the early 1940s toward acceptance of the principle of integrated schooling. ... by 1985, more than nine out of ten chose the pro-integration response.

- ^ Healey, Joseph F.; O'Brien, Eileen (May 8, 2007). Race, Ethnicity, and Gender: Selected Readings. Pine Forge Press. ISBN 978-1-4129-4107-5.

In 1942 only 42 percent of a national sample of whites reported that they believed blacks to be equal to whites in innate intelligence; since the late 1950s, however, around 80 percent of white Americans have rejected the idea of inherent black inferiority.

- ^ Winant, Howard (1997). "Behind Blue Eyes: Whiteness and Contemporary US Racial Politics". New Left Review (225): 73. ISBN 978-0-415-94964-4. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2020 – via Google Books: «Off White: Readings on Power, Privilege, and Resistance».

white racial attitudes shifted dramatically in the postwar period. ... So, monolithic white supremacy is over, yet in a more concealed way, white power and privilege live on.

- ^ Berlet, Chip; Lyons, Matthew N. (March 8, 2018). Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort. Guilford Publications. ISBN 978-1-4625-3760-0.

While the New Right and Christian Right flourished in the 1970s and 1980s, the Far Right also rebounded... The Far Right—encompassing Ku Klux Klan, neonazi, and related organizations—attracted a much smaller following than the New Right, but its influence reverberated in its encouragement of widespread attacks against members of oppressed groups and in broad-based scapegoating campaigns

- ^ Belew, Kathleen (2018). Bring the war home: The white power movement and paramilitary America. ISBN 978-0-674-28607-8.

The white power movement that emerged from the Vietnam era shared some common attributes with earlier racist movements in the United States, but it was no mere echo. Unlike previous iterations of the Ku Klux Klan and white-supremacist vigilantism, the white power movement did not claim to serve the state. Instead, white power made the state its target, declaring war against the federal government in 1983.

- ^ Blanchfield, Patrick (June 20, 2018). "Declaration of War: The violent rise of white supremacy after Vietnam (How Did Vietnam Transform White Supremacy?)". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Perliger, Arie (2012). Challengers from the Sidelines: Understanding America's Violent Far-Right. West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, US Military Academy.

- ^ "U.S. sees 300 violent attacks inspired by far right every year". PBS NewsHour. August 13, 2017. Archived from the original on August 11, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ Winant, Howard (1997). "Behind Blue Eyes: Whiteness and Contemporary US Racial Politics". New Left Review (225): 73.

- ^ Stanley, Jason (2018). How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House. p.13. ISBN 978-0-52551183-0

- ^ Inwood, Joshua (2019). "White supremacy, white counter-revolutionary politics, and the rise of Donald Trump". Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. 37 (4): 579–596. doi:10.1177/2399654418789949. ISSN 2399-6544. S2CID 158269272. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Bobo, Lawrence D. (n.d.). "Racism in Trump's America: reflections on culture, sociology, and the 2016 US presidential election". The British Journal of Sociology. 68 (S1): S85 – S104. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12324. ISSN 1468-4446. PMID 29114872. S2CID 9714176.

- ^ "Cornel West on Donald Trump: This is What Neo-Fascism Looks Like". Democracy Now!. December 1, 2016. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Politics of Gender: Women, Men, and the 2016 Campaign". The Atlantic. December 13, 2016. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Hughes, Trevor. "Number of white and black hate groups surge under Trump, extremist-tracking organization says". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ Chalfant, Morgan (July 23, 2019) "FBI's Wray says most domestic terrorism arrests this year involve white supremacy" Archived September 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine The Hill

- ^ Sands, Geneva (September 20, 2019) "Homeland Security counterterrorism strategy focuses on white supremacy threat" Archived September 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine CNN

- ^ Williams, Pete (September 20, 2019) "Department of Homeland Security strategy adds white supremacy to list of threats" Archived September 21, 2019, at the Wayback Machine NBC News

- ^ "How White Women Use Themselves as Instruments of Terror". The New York Times. May 27, 2020. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ "Lynchings: By State and Race, 1882–1968". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on June 29, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

- ^ "History of Lynchings". NAACP. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Wood, Amy Louise (2005). "Lynching Photography and the Visual Reproduction of White Supremacy". American Nineteenth Century History. 6 (3): 373–399. doi:10.1080/14664650500381090. ISSN 1466-4658. S2CID 144176806.

- ^ Brown, M. Christopher, (2005). The Politics of Curricular Change : Race, Hegemony, and Power in Education. Land, Roderic R., 1975–. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 0-8204-4863-X. OCLC 1066531199.

- ^ a b c Mills, Charles W. (1994). "REVISIONIST ONTOLOGIES: THEORIZING WHITE SUPREMACY". Social and Economic Studies. 43 (3): 105–134. ISSN 0037-7651.

- ^ a b Carter G. Woodson (Carter Godwin) (1993). The mis-education of the Negro. Internet Archive. Trenton, N.J. : AfricaWorld Press. ISBN 978-0-86543-171-3.

- ^ Boutte, Gloria Swindler (2008). "Beyond the Illusion of Diversity: How Early Childhood Teachers Can Promote Social Justice". The Social Studies. 99(4): 165–173. doi:10.3200/TSSS.99.4.165-173. ISSN 0037-7996.

- ^ a b c Elson, Ruth Miller (1964). Guardians of Tradition: American Schoolbooks of the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ a b Swartz, Ellen (1992). "Emancipatory Narratives: Rewriting the Master Script in the School Curriculum". The Journal of Negro Education. 61(3): 341–355. doi:10.2307/2295252. ISSN 0022-2984.

- ^ a b c d e f Au, Wayne, 1972–. Reclaiming the multicultural roots of U.S. curriculum : communities of color and official knowledge in education. Brown, Anthony Lamar, Aramoni Calderón, Dolores, Banks, James A.,. New York. ISBN 978-0-8077-5678-2. OCLC 951742385.

- ^ a b Brown, Anthony L. (2010). "Counter-memory and Race: An Examination of African American Scholars' Challenges to Early Twentieth Century K-12 Historical Discourses". The Journal of Negro Education. 79 (1): 54–65. ISSN 0022-2984. JSTOR 25676109.

- ^ Stout, Mary, 1954– (2012). Native American boarding schools. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-38676-3. OCLC 745980477.

- ^ Lander, Samuel (1863). Our Own School Arithmetic, Greensboro, N.C.: Sterling, Campbell, and Albright, in Elson, Ruth Miller (1964). Guardians of Tradition: American Schoolbooks of the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ The El Paso shooting isn't an anomaly. It's American history repeating itself. Why white supremacist violence is rising today — and how it echoes some of the darkest moments of our past, by Zack Beauchamp, Vox, Aug 6, 2019 Archived August 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Chow, Kat (December 8, 2018) "What The Ebbs And Flows Of The KKK Can Tell Us About White Supremacy Today" Archived December 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine NPR

- ^ Beckett, Lois (July 31, 2020). "Twitter bans white supremacist David Duke after 11 years". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 19, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Diep, Francie (August 15, 2017). "How Social Media Helped Organize and Radicalize America's White Supremacists". Pacific Standard. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Bennett-Smith, Meredith (July 2, 2013). "'The Andrew Show,' Hosted By Pint-Sized Andrew Pendergraft, Markets Klan's Racist Message To Kids". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Harrison, Berry (January 25, 2017). "Fliers For Nationalist Organization Appear at Boise State". Boise Weekly. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Blanchard, Nicole (January 26, 2017). "BSU nationalist group delays 1st meeting after online pushback, media reports". Idaho Statesman. Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Heyden, Tom (January 26, 2015). "The 10 greatest controversies of Winston Churchill's career". BBC News. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (2018). Churchill: Walking With Destiny. London: Allen Lane. pp. 414–15. ISBN 978-0-241-20564-8. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Baldwin-Ragaven, Laurel; London, Lesley; du Gruchy, Jeanelle (1999). An ambulance of the wrong colour: health professionals, human rights, and ethics in South Africa. Juta and Company Limited. p. 18

- ^ John Pilger (2011). "Freedom Next Time". p. 266. Random House

- ^ "abolition of the White Australia Policy". Australian Government. November 2010. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica, South Africa the Apartheid Years". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 28, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Gann, L.H. Politics and Government in African States 1960–1985. pp. 162–202.

- ^ Nelson, Harold. Zimbabwe: A Country Study. pp. 1–317.

- ^ Blamires, Cyprian; Jackson, Paul. "World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia": Volume 1. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, Inc, 2006. p. 62.

- ^ Though Rosenberg does not use the word "master race". He uses the word "Herrenvolk" (i. e., ruling people) twice in his book The Myth, first referring to the Amorites (saying that Sayce described them as fair skinned and blue eyed) and secondly quoting Victor Wallace Germains' description of the English in "The Truth about Kitchener". ("The Myth of the Twentieth Century") – Pages 26, 660 – 1930

- ^ Stoddard, Lothrop (1922). The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under Man. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Losurdo, Domenico (2004). "Toward a Critique of the Category of Totalitarianism" (PDF, 0.2 MB). Historical Materialism. 12 (2). Translated by Marella & Jon Morris: 25–55, here p. 50. doi:10.1163/1569206041551663. ISSN 1465-4466. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ Rosenberg, Alfred (1930). Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts: Eine Wertung der seelischgeistigen Gestaltungskämpfe unserer Zeit [The Myth of the Twentieth Century] (in German). Munich: Hoheneichen-Verlag. p. 214. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012.

- ^ "American laws against 'coloreds' influenced Nazi racial planners" Archived August 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Times of Israel. Retrieved August 26, 2017

- ^ a b Whitman, James Q. (2017). Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press. pp. 37–43.

- ^ Henry Friedlander. The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA: University of North Carolina Press, 1995. p. 5.

- ^ "Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz – Verfassungsschutzbericht 2012". Archived from the original on March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Christchurch killer to stay in jail until he dies". BBC News. August 27, 2020. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Brenton Tarrant: White supremacist sentenced to life without parole for killing 51 Muslims in New Zealand mosque attacks". Sky News. Archived from the original on August 27, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Staff, Our Foreign (August 27, 2020). "New Zealand mosque shooting: 'Wicked and inhuman' Brenton Tarrant sentenced to life without parole". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Massey Uni named after racist PM, lecturer says". RNZ. September 29, 2016. Archived from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Tuckey, Karoline (September 29, 2016). "Massey racism provokes call for university name change". Stuff. Archived from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Elers, Steve (July 1, 2018). "A 'white New Zealand': Anti-Chinese Racist Political Discourse from 1880 to 1920". China Media Research. 14 (3): 88–99. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "William Massey was a Racist". Massive Magazine. Archived from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Nordicism". Merriam Webster. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1851). Parerga and Paralipomena. pp. Vol. 2, Section 92.

- ^ Grant, Madison (1921). The Passing of the Great Race (4 ed.). C. Scribner's sons. p. xxxi.

- ^ Grant, Madison (1916). The Passing of the Great Race. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

- ^ Armstrong. Eric M. (February 6, 2010). "Revered and Reviled: D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation'". The Moving Arts Film Journal. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Gumkowski, Janusz; Leszczynski, Kazimierz; Robert, Edward (translator) (1961). Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe (PAPERBACK). Poland Under Nazi Occupation (First ed.) (Polonia Pub. House). ASIN B0006BXJZ6. Retrieved March 12, 2014. at Wayback machine.

- ^ Peter Longerich (April 15, 2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ "Close-up of Richard Jenne, the last child killed by the head nurse at the Kaufbeuren-Irsee euthanasia facility". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Profile in Power, Chapter VI, first section (London, 1991, rev. 2001)

- ^ Snyder, S. & D. Mitchell. Cultural Locations of Disability. University of Michigan Press. 2006.

- ^ The new white nationalism in America: its challenge to integration. Cambridge University Press. June 10, 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-80886-6. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

For instance, Ben Klassen, founder of the atheistic Church of the Creator and author of The White Man's Bible, discusses Christianity extensively in his writings and denounces it as a religion that has brought untold horror into the world and has divided the white race.

- ^ The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. Taylor & Francis. May 7, 2009. ISBN 978-1-135-21100-4. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

A competing atheistic or panthestic white racist movement also appeared, which included the Church of the Creator/ Creativity (Gardell 2003: 129–34).

- ^ "Smiling Smash: An Interview with Cathal Smyth, a.k.a. Chas Smash, of Madness". Archived from the original on February 19, 2001. Retrieved February 19, 2001..

- ^ Special Articles Archived December 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Old Skool Jim. Trojan Skinhead Reggae Box Set liner notes. London: Trojan Records. TJETD169.

- ^ Adams, Josh; Roscigno, Vincent J. (November 20, 2009). "White Supremacists, Oppositional Culture and the World Wide Web". Social Forces. 84 (2): 759–778. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0001. JSTOR 3598477. S2CID 144768434.

- ^ Dobratz, Betty A. & Shanks-Meile, Stephanie L. (Summer 2006). "The Strategy of White Separatism". Journal of Political and Military Sociology. 34 (1): 49–80. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007.

- ^ "White Separatism". ADL. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ "SPLC reacts to Facebook policy on white nationalism". SPLC. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ "Standing Against Hate". Facebook. March 27, 2019. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook to ban white nationalism and separatism". BBC News. March 28, 2019. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ "ADL: White Separatism". adl.org. The Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Dobratz, Betty A. & Shanks-Meile, Stephanie L. (2000) The White Separatist Movement in the United States: "White Power, White Pride!. Baltimore: JHU Press. pp.vii, 10

- ^ Dobratz, Betty A. & Shanks-Meile, Stephanie L. (1997). The White Separatist Movement in the United States: White Power, White Pride!. New York: Twayne Publishers. pp. ix, 12. ISBN 978-0-8057-3865-0. OCLC 37341476.

- ^ Daniels, Jessie (1997). White Lies: race, class, gender and sexuality in white supremacist discourse. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-91289-1.

- ^ Fuller, Neely (1984). The united-independent compensatory code/system/concept: A textbook/workbook for thought, speech, and/or action, for victims of racism (white supremacy). SAGE. p. 334. ASIN B0007BLCWC.

- ^ Davidson, Tim (February 23, 2009). "bell hooks, white supremacy, and the academy". In Jeanette Davidson; George Yancy (eds.). Critical perspectives on bell hooks. Taylor & Francis US. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-415-98980-0.

- ^ "Why is it so difficult for many white folks to understand that racism is oppressive not because white folks have prejudicial feelings about blacks (they could have such feelings and leave us alone) but because it is a system that promotes domination and subjugation?" hooks, bell (February 4, 2009). Black Looks: Race and Representation. Turnaround Publisher Services Limited. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-873262-02-3.

- ^ Grillo and Wildman cite hooks to argue for the term racism/white supremacy: "hooks writes that liberal whites do not see themselves as either prejudiced or interested in domination through coercion, and they do not acknowledge the ways in which they contribute to and benefit from the system of white privilege." Grillo, Trina; Stephanie M. Wildman (June 29, 1997). "The implications of making comparisons between racism and sexism (or other isms)". In Richard Delgado; Jean Stefancic (eds.). Critical white studies: Looking behind the mirror. Temple University Press. p. 620. ISBN 978-1-56639-532-8.

- ^ McWhorter, John (June 22, 2020). "The Dictionary Definition of 'Racism' Has to Change". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "Left Language, Right Language". Wnyc. Archived from the original on September 21, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ McWhorter, John. "The Difference Between Racial Bias and White Supremacy". TIME. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ "Let's Be Careful With the "White Supremacy" Label". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Friedersdorf, Conor. "'The Scourge of the Left': Too Much Stigma, Not Enough Persuasion". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

Further reading

- Almaguer, Tomás. (2008) Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1994.

- Brooks, Michael E. and Fitrakis, Robert (2021). A History of Hate in Ohio: Then and Now. The Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-5800-2

- Baird, Robert P. (April 20, 2021). "The invention of whiteness: the long history of a dangerous idea". The Guardian.

- Bessis, Sophie (2003) Western Supremacy: The Triumph of an Idea. Zed Books. ISBN 9781842772195 ISBN 1842772198

- Dobratz, Betty A. and Shanks-Meile, Stephanie (2000) "White Power, White Pride!": The White Separatist Movement in the United States. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6537-4

- Horne, Gerald. (2017) The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery White Supremacy and Capitalism in Seventeenth-Century North America and the Caribbean. New York: Monthly Review Press; ISBN 978-1-58367-663-9.

- Horne, Gerald. (2020). The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery White Supremacy Settler Colonialism and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-872-5.

- MacCann, Donnarae (2000) White Supremacy in Children's Literature: Characterizations of African Americans, 1830–1900. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415928908

- Van der Pijl, Kees, The Discipline of Western Supremacy: Modes of Foreign Relations and Political Economy, Volume III, Pluto Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-7453-2318-3

External links

- Heart of Whiteness—A documentary film about what it means to be white in South Africa

- "Voices on Antisemitism"—Interview with Frank Meeink from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- "Russell Moore: White supremacy angers Jesus, but does it anger his church?"—The president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention

- "Exterminate All the Brutes, Reviewed: A Vast, Agonizing History of White Supremacy" (HBO Series), by Richard Brody, April 9, 2021, The New Yorker