The Passing of the Great Race

Title page of the first 1916 edition of The Passing of the Great Race. | |

| Author | Madison Grant |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | |

| Publisher | Charles Scribner's Sons |

Publication date | 1916 |

| Publication place | United States |

| OCLC | 400188 |

| LC Class | GN575 .G75 1921 |

| Part of a series on |

| Eugenics in the United States |

|---|

The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific[1][2] book by American lawyer, anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theory of Nordic superiority, claiming that the "Nordic race" is inherently superior to other human "races". The theory and the book were praised by Adolf Hitler and other Nazis.

Contents

[edit]First section

[edit]

The first section deals with the basis of race as well as Grant's own stances on political issues of the day (eugenics). These center around the growing numbers of immigrants from non-Nordic Europe. Grant claims that the members of contemporary American Protestant society who could trace their ancestry back to Colonial times were being out-bred by immigrant and "inferior" lower-class White racial stocks. Grant reasons that the United States has always been a Nordic country, consisting of Nordic immigrants from England, Scotland, and the Netherlands in Colonial times and of Nordic immigrants from Ireland and Germany in later times. Grant claims that certain parts of Europe were underdeveloped and a source of racial stocks unqualified for the Nordic political structure of the US. Grant is also interested in the impact of the expansion of the US Black population into the urban areas of the North.

Grant reasons that the new immigrants were of different races and were creating separate societies within America including ethnic lobby groups, criminal syndicates, and political machines which were undermining the socio-political structure of the country and in turn the traditional Anglo-Saxon colonial stocks, as well as all Nordic stocks. His analysis of population studies, economic utility factors, labor supply, etc. purports to show that the consequence of this subversion was evident in the decreasing quality of life, lower birth rates, and corruption of the contemporary American society. He reasons that the Nordic races would become extinct and the United States as it was known would cease to exist, being replaced by a fragmented country, or a corrupted caricature of itself.

Second section

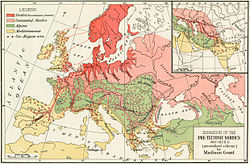

[edit]The second part of the book reviews European prehistory as it was known at the time of writing of the book, and then postulates the existence of three European races, which Grant defines as Nordic, Alpine, and Mediterranean, as well as their physical and mental characteristics. He then speculates hereditary links between the proposed Nordic people and the Trojans[3]: 159 and between the Prussians and the Spartans.[3]: 160 This part of the book ties together strands of speculation regarding Aryan migration theory, ethnology, anthropology, and history into a broad survey of the historical rise and fall, and expansion and retraction, of the European races from their homelands.

Nordicism

[edit]

This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. (July 2023) |

The book elaborates Grant's interpretation of contemporary anthropology and history, which he sees as revolving chiefly around "race" rather than environment. He specifically promotes the idea of the Nordic race as a key social group responsible for human development; thus the subtitle of the book is The Racial Basis of European History. Grant also supports eugenics, advocating the sterilization of "undesirables", a treatment possibly to be extended to "types which may be called weaklings" and "perhaps ultimately to worthless race types": "A rigid system of selection through the elimination of those who are weak or unfit—in other words social failures—would solve the whole question in one hundred years, as well as enable us to get rid of the undesirables who crowd our jails, hospitals, and insane asylums. The individual himself can be nourished, educated and protected by the community during his lifetime, but the state through sterilization must see to it that his line stops with him, or else future generations will be cursed with an ever increasing load of misguided sentimentalism. This is a practical, merciful, and inevitable solution of the whole problem, and can be applied to an ever widening circle of social discards, beginning always with the criminal, the diseased, and the insane, and extending gradually to types which may be called weaklings rather than defectives, and perhaps ultimately to worthless race types."

Other messages in his work include recommendations to install civil organizations through the public health system to establish quasi-dictatorships in their particular fields with the administrative powers to segregate unfavorable races in ghettos. He also mentions that the expansion of non-Nordic race types in the Nordic system of freedom would actually mean a slavery to desires, passions, and base behaviors. In turn, this corruption of society would lead to the subjection of the Nordic community to "inferior" races who would in turn long to be dominated and instructed by "superior" ones utilizing authoritarian powers. The result would be the submergence of the indigenous Nordic races under a corrupt and enfeebled system dominated by inferior races.

Grant's view of Nordicism

[edit]Nordic theory, in Grant's formulation, was largely copied from the work of Arthur de Gobineau that appeared in the 1850s, except that Gobineau used the study of language while Grant used physical anthropology to define races. Both divided mankind into primarily three distinct races: Caucasoids (based in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia), Negroids (based in Sub-Saharan Africa), and Mongoloids (based in Central and Eastern Asia). Nordic theory, however, further subdivided Caucasoids into three groups: Nordics (who inhabited Scandinavia, northern Germany, parts of England, Scotland and Ireland, Holland, Flanders, parts of northern France, parts of Russia and northern Poland, and parts of Central Europe), Alpines (whose territory stretched from central Europe, parts of northern Italy, southern Poland to the Balkans/Southeastern Europe, central/southern Russia, Turkey and even into Central Asia), and Mediterraneans ("substantial part of the population of the British Isles, the great bulk of the population of the Iberian Peninsula, nearly one-third of the population of France, Liguria, Italy south of the Apennines and all the Mediterranean coasts and islands, in some of which like Sardinia it exists in great purity. It forms the substratum of the population of Greece and of the eastern coast of the Balkan Peninsula.")[4][third-party source needed]

In Grant's view, Nordics probably evolved in a climate which "must have been such as to impose a rigid elimination of defectives through the agency of hard winters and the necessity of industry and foresight in providing the year's food, clothing, and shelter during the short summer. Such demands on energy, if long continued, would produce a strong, virile, and self-contained race which would inevitably overwhelm in battle nations whose weaker elements had not been purged by the conditions of an equally severe environment" (p. 170). The "Proto-Nordic" human, Grant reasoned, probably evolved in "forests and plains of eastern Germany, Poland and Russia" (p. 170).

The Nordic, in his hypothesis, was "Homo europaeus, the white man par excellence. It is everywhere characterized by certain unique specializations, namely, wavy brown or blond hair and blue, gray or light brown eyes, fair skin, high, narrow and straight nose, which are associated with great stature, and a long skull, as well as with abundant head and body hair."[3] Grant categorized the Alpines as being the lowest of the three European races, with the Nordics as the pinnacle of civilization: "The Nordics are, all over the world, a race of soldiers, sailors, adventurers, and explorers, but above all, of rulers, organizers, and aristocrats in sharp contrast to the essentially peasant character of the Alpines. Chivalry and knighthood, and their still surviving but greatly impaired counterparts, are peculiarly Nordic traits, and feudalism, class distinctions, and race pride among Europeans are traceable for the most part to the north."

Grant, while aware of the hypothesized "Nordic migration" into the Mediterranean, appears to reject this theory as an explanation for the high civilization features of the Greco-Roman world: "The mental characteristics of the Mediterranean race are well known, and this race, while inferior in bodily stamina to both the Nordic and the Alpine, is probably the superior of both, certainly of the Alpines, in intellectual attainments. In the field of art its superiority to both the other European races is unquestioned."[third-party source needed]

Yet, while Grant allowed Mediterraneans to have abilities in art, as quoted above, he remarked later in the text that true Mediterranean achievements were only through admixture with Nordics: "This is the race that gave the world the great civilizations of Egypt, of Crete, of Phoenicia including Carthage, of Etruria and of Mycenean Greece. It gave us, when mixed and invigorated with Nordic elements, the most splendid of all civilizations, that of ancient Hellas, and the most enduring of political organizations, the Roman State. To what extent the Mediterranean race entered into the blood and civilization of Rome, it is now difficult to say, but the traditions of the Eternal City, its love of organization, of law and military efficiency, as well as the Roman ideals of family life, loyalty, and truth, point clearly to a Nordic rather than to a Mediterranean origin."[third-party source needed]

In this manner, Grant appeared to be studiously following scientific theory. Critics warned that Grant used uncritical circular reasoning.[5] His desirable characteristics of a people — "family life, loyalty, and truth" — were claimed to be exclusive products of the "Nordic race".[6] Thus, whenever such traits were found in a non-Nordic culture, Grant said that they were evidence of a Nordic influence or admixture, rather than casting doubt on their supposed exclusive Nordic origin.

Reception and influence

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

According to historian Charles C. Alexander writing for the journal Phylon in 1962: "There was nothing very new about The Passing of the Great Race; Grant's views were essentially a reiteration of the earlier racial polemics of the Comte de Gobineau in France and Houston Stewart Chamberlain in Germany. What gave the book particular significance was the boldness and sweep of the treatment. Grant demonstrated his eclecticism by taking the Anglo-Saxon tradition, borrowing a bit of racial philosophy from one writer, a bit from another, and weaving together a comprehensive view of history. He bade fare well to Christian and democratic values."[7]

By 1937, the book had sold 17,000 copies in the U.S. The book received positive reviews in the 1920s, but Grant's popularity declined in the 1930s. Among those who embraced the book and its message was Adolf Hitler, who wrote to Grant to personally thank him for writing it, referring to the book as "my Bible."[8]

Spiro (2009) writes that its sales were limited for various reasons including anti-German sentiments in the United States with the outbreak of the First World War, the book's anti-democratic and anti-Christian messages and its hereditarianism, which ran counter to traditional American pride in democracy and hard work, and its categorization as a "science" work, which alone meant it "never really had a chance at mass popularity".[9]

According to Grant, Nordics were in a dire state in the modern world, where after their abandonment of cultural values rooted in religious or superstitious proto-racialism, they were close to committing "race suicide" by miscegenation and being outbred by inferior stock, which was taking advantage of the transition. Nordic theory was strongly embraced by the racial hygiene movement in Germany in the early 1920s and 1930s; however, they typically used the term "Aryan" instead of "Nordic", though the principal Nazi ideologist, Alfred Rosenberg, preferred "Aryo-Nordic"[citation needed] or "Nordic-Atlantean". Stephen Jay Gould described The Passing of the Great Race as "the most influential tract of American scientific racism".[10]

Grant was involved in many debates on the discipline of anthropology against the anthropologist Franz Boas, who advocated cultural anthropology in contrast to Grant's "hereditarian" branch of physical anthropology. Boas and his students were strongly opposed to racialist notions, holding that any perceived racial inequality was from social rather than biological factors.[11] Versions of their debates on the relative influence of biological and social factors persist in contemporary anthropology.[12]

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from East Asia and Southern Europe; he also advocated efforts to purify the American population though selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the Immigration Restriction League from 1922 to his death in 1937. Acting as an expert on world racial data, Grant also provided statistics for the Immigration Act of 1924 to set the quotas on immigrants from certain European countries. He also assisted in the passing and prosecution of several anti-miscegenation laws, notably the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 in the state of Virginia, where he sought to codify his particular version of the "one-drop rule" into law.[citation needed]

Grant became a part of popular culture in 1920s America. Author F. Scott Fitzgerald made a lightly disguised reference to Grant in The Great Gatsby. In the book, the character Tom Buchanan reads a book called The Rise of the Colored Empires by "this man Goddard", a combination of Grant and his colleague Lothrop Stoddard. (Grant wrote the introduction to Stoddard's book The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy.) "Everybody ought to read it", the character explained. "The idea is if we don't look out the white race will be — will be utterly submerged. It's all scientific stuff; it's been proved."[13][14]

Ernest Hemingway might also have alluded to The Passing of the Great Race in the subtitle of his book The Torrents of Spring; A Romantic Novel in Honor of the Passing of a Great Race. The book was a parody of contemporary writers and would thus be referring to them sarcastically as a "great race".[citation needed]

Americans turned against Grant's ideas in the 1930s; his book was no longer sold, and his supporters fell away.[15] In Europe, however, Nordic theory was adopted during the 1930s by the Nazis and others. Grant's book and the genre in general were read in Germany, but eugenicists increasingly turned to Nazi Germany for leadership. Heinrich Himmler's Lebensborn ("Fount of Life") Society was formed to preserve typical Nordic genes, such as blond hair and blue eyes, by sheltering blonde, blue-eyed women.[16]

The book continued to influence the white supremacist movement in the United States in the early 21st century.[17] The book was also the earliest emergence of the white genocide conspiracy theory as The Passing of the Great Race specifically focuses on the "race suicide" of Nordics.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ Hoff, Aliya R. (12 July 2021). "Embryo Project Encyclopedia: The Passing of the Great Race; or The Racial Basis of European History (1916), by Madison Grant". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Alexander, Charles C. (1962). "Prophet of American Racism: Madison Grant and the Nordic Myth". Phylon. 23 (1). Clark Atlanta University: 79. doi:10.2307/274146. JSTOR 274146.

- ^ a b c Grant, Madison (1921). The Passing of the Great Race (4 ed.). C. Scribner's Sons. p. 167.

- ^ Grant, Madison (1918). The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 152.

- ^ Spiro, Jonathan P. (2009). Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. University of Vermont Press. ISBN 978-1-58465-715-6.

- ^ Madison Grant, The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History (New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916), p. 139.

- ^ Alexander, Charles C. (1962). "Prophet of American Racism: Madison Grant and the Nordic Myth". Phylon. 23 (1): 77. doi:10.2307/274146. JSTOR 274146. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Stefan Kühl. Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism (Oxford University Press, 2002) p. 85

- ^ Spiro (2009) p 161

- ^ Stephen Jay Gould, Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History (New York, New York: W. W. Norton, 1991), p. 162.

- ^ Baker (1998), 104-107

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (8 October 2002). "A New Look at Old Data May Discredit a Theory on Race". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Lindgren, Allana; Ross, Stephen (2015-06-05). The Modernist World. Routledge. pp. 504–505. ISBN 978-1-317-69616-2.

- ^ Fitzgerald, F. Scott (2003-05-27). The Great Gatsby: The Only Authorized Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-4639-2.

- ^ Spiro (2009) p 347

- ^ Spiro (2009) p 363-64

- ^ Berlet, Chip; Vysotsky, Stanislav (2006). "Overview of U.S. White Supremacist Groups". Journal of Political and Military Sociology. 34 (1): 14.

- ^ Serwer, Adam (April 2019). "Adam Serwer: White Nationalism's Deep American Roots". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Baker, Lee D. (1998). From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction of Race. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21168-5.

- Guterl, Matthew Press (2001). The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00615-1.

- Jackson, John P. (2005). Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case against Brown v. Board of Education. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4271-6.

- Lay summary in: "Book Review: Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case Against Brown v. Board of Education". History Cooperative.

- Tucker, William H. (2007). The funding of scientific racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07463-9.

External links

[edit]- Passing of the Great Race available online via The Internet Archive

The Passing of the Great Race public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Passing of the Great Race public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Excerpts from Passing of the Great Race used at the Nuremberg Trials

- Passing of the Great Race (1921 ed.), available via Google Books