Wellington tramway system

| Wellington tramway system | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The last regular tram service in New Zealand, c. 2 May 1964 | |||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||

| Locale | |||||||||||||||||

| Open | 24 August 1878 | ||||||||||||||||

| Close | 2 May 1964 | ||||||||||||||||

| Status | Closed | ||||||||||||||||

| Routes | 11[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Owner(s) | Wellington City Council (from 1 August 1900) | ||||||||||||||||

| Infrastructure | |||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft (1,219 mm) | ||||||||||||||||

| Propulsion system(s) | Steam (1878-1882) Horse-drawn (1882-1904) Electric (from 1904) | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

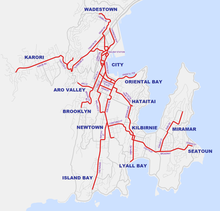

The Wellington tramway system (1878–1964) operated in Wellington, the capital of New Zealand.[6] The tramways were initially owned by a private company but were purchased by the city and formed a significant part of the city's transport system. Historically, it was an extensive network, with steam and horse trams from 1878, and then electric trams ran from 1904 to 1964 when the last line from Thorndon to Newtown was replaced by buses.

In 1878, Wellington's trams were steam-powered, with an engine drawing a separate carriage.[7] The engines were widely deemed unsatisfactory, however — they created a great deal of soot, were heavy (increasing track maintenance costs), and often frightened horses.[8][9] By 1882, a combination of public pressure and financial concerns caused the engines to be replaced by horses.[10][11] In 1902, after the tramways came into public ownership, it was decided to electrify the system, and the first electric tram ran in 1904.[12] Trams operated singly and were mostly single-deck with some (open-top) double-deck.[13]

Wellington's more northern suburbs, such as Johnsonville and Tawa, were not served by the tram network, as they were (and are) served by the Wellington railway system.[14][15] The Wellington Cable Car, another part of Wellington's transport network, is sometimes described as a tram but is not generally considered so, being a funicular railway.[16][17] It was opened in 1902 and is still in operation.[18] Wellington's electric tramways had an unusual gauge of 4 ft (1,219 mm), a narrow gauge. The steam and horse trams were 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge, which was also narrow and the same as New Zealand's national railway gauge.[19][20]

Background

[edit]In 1872, the Tramways Act was passed, which allowed for the construction of tramways so local authorities and private companies could run them.[21][22] The following year, Charles O'Neill proposed a plan to lay down tracks and operate a tramway submitted to the Wellington City Council.[23]

A deed was awarded to O'Neill on 23 March 1876, granted by the City Council.[24] The deed granted the power to construct a tramway, with O'Neill and his team committing to start works within six months and finish within 18 months. The agreement was for ten years, with the City Council having the right to extend the line at any time.[24] The City Council had the right to purchase the tramway after 10 years or to remove the tracks.[24]

On 29 June 1876, William Fitzherbert signed the order authorising the construction of the tramways, which confirmed the terms of the City Council's deed.[25] On 9 January 1877, locomotives, carriages, and rails had been ordered from England.[26] The steam trams were manufactured by Merryweather & Sons in London, and 14 tram trailers originated from New York and were manufactured by John Stephenson Company.[27][28] The larger trailers could accommodate 22 passengers, while the smaller ones held 14.[28]

On 14 November of the same year, the Wellington City Tramways Company Ltd was formed.[29] Laborers who were hired to lay the tracks were paid 10 shillings daily, while carpenters earned 14 shillings. The rails arrived on the sailing ship Broomhall in July 1877. The tramway was designed as a single-track, complete with sidings, passing loops, and crossings. The track was laid on sleepers made of Totara or Rimu, resting on a gravel bed.[29]

History

[edit]Early tramways: 1878-1900

[edit]Steam tram

[edit]

The first tram line in Wellington opened on 24 August 1878 for £NZ40,000.[30][31] The line was 4.5 km in length and 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge and ran between the north end of Lambton Quay and a point just south of the Basin Reserve with the Governor, the Marquess of Normanby riding the first tram at 10 km/h.[32][33][34] The Tramways Company claimed in their opening day speech it was the first steam-tram in the southern hemisphere but Thames had any existence steam tramway since 1871.[35][28]

During its early operation, the tramway boasted four steam trams, each connected to passenger trailers for seating.[36][37] Additionally, the tramway company operated two horse-drawn cars that were used to transport some passengers.[36][38] At its peak, the fleet expanded to eight steam tram engines, each costing approximately £NZ975. Each engine consumed around 78 cwt of coal for 12 hours of operation.[24]

The steam trams caused complaints over noise, being a nuisance, soot, frightened horses, and collisions, which led to civil court cases.[39][34][40] They proved unpopular with cabmen, carters, and some residents, who organised a meeting.[36] It was decided to petition for their removal.[41] On 4 December 1879, a petition was handed over to Governor Hercules Robinson requesting the use of animal power only for Wellington's trams.[42] Robinson gave them a sympathetic hearing.[42] It was alleged that cabmen used to block the way of the steam trams deliberately.[43]

The Wellington City Tramways Company went into voluntary liquidation in 1879 because the rails were too light for the steam trams' weight. The cost to maintain the rails was too high for the company to continue, and they were to be sold to a private owner.[44] [45] A shareholder meeting was held on 8 January 1880 to agree that the company should be wound up voluntarily and formally.[46] In March 1880, an auction was held, and the new owner was the sole bidder, Edward William Mills, who bid £NZ19,250 and became the director.[47]

Horse trams

[edit]

In January 1882, introducing horse-drawn trams led to removing steam trams from service.[48] An additional route along Courtenay Place was opened. King Street Depot became a horse stable, replacing the Adelaide Road engine shed. The then-new horse stable was made to hold 50 horses and was gradually enlarged to 140 horses.[49][50][51] The horses were brought over from the Wairarapa to pull the trams, and chaff was obtained from Sanson.[51]

Horse-drawn trams retained the same passenger trailers as the old steam tram services.[52] In February 1884, the old steam trams were auctioned off, but one of the steam trams was retained as a chaff cutter for the horses' feed.[28] The Tramway Company's deed with the City Council was due to expire in July 1887. A council-appointed committee recommended buying the tramway. However, the Council didn't proceed at this stage.[53]

In May 1900, the City Council held a meeting on purchasing the Wellington City Tramways and their rolling stock, horses, tools, and rails.[54] In June 1900, City Council gave public notice of its intent to purchase the Wellington City Tramways.[55] On 1 October 1900, the City Council became the owner, paying £NZ19,382. The Wellington Corporation Tramways Department was established to manage the tram service.[56] The Wellington City Council purchased the tram company and took over from 1 August 1900, although it was not until 1902 that the street lease expired.[57][58]

Electric era: 1901–1964

[edit]Electrification

[edit]

Reports from the United States and England highlighted the innovation of trams powered by electricity, with current supplied through overhead wires.[59] In response to these reports, the City Council conducted inquiries into the electrification and extension of the tramway by 1901 and decided to implement electric trams.[59][50] Plans for the project were presented to the city's ratepayers, who approved the initiative.[60] In 1902, the City Council borrowed £NZ225,000 through the Tramways Department. It employed the funds for the extension and electrification of the tramway network.[61] A contract was signed in the same year to electrified the system.[62]

The tracks were to be converted to the then-new 4 ft (1,219 mm) gauge, which was adopted because of the narrow streets in Wellington Central.[63][64] The trams used electric power to move along rails, requiring extensive infrastructure like overhead wires and tram poles.[65] A London-based firm was awarded £NZ110,000 to lay tracks, install the overhead wire, provide wooden blocks, and set up tram poles.[66][59] The electric system featured 33 trams, and about half were double-deck vehicles manufactured in England.[48][59]

Tram poles were made of steel sections with a slightly tapered diameter. Topped with a ball and spike finial for ornamental and water protection, bracket arms carried a double insulation system for overhead wires to power them to 500-550 volts.[67] The tram poles were 25 feet tall, and workers used derricks to lift the poles and drop them through the holes they made in the footpath, where they were then encased in six feet of concrete.[68][69]

As the electric trams were being introduced to Wellington, tram poles became a means of ornamentation the city, resulting in elaborately designed poles. Decorative steel centre poles were embellished with wrought ironwork. On less central streets, tram poles were simpler in design but still included moulded bases, ferrules, and finials, typically featuring a ball and spike style.[70]

The tram utilised various devices to collect power from overhead lines, with a roof-mounted trolley pole being the most common—the trolley pole connected to the overhead line was maintained by pressure from the spring-loaded trolley base.[68] City of Wellington Electric Light and Power Company was commissioned to operate a £NZ25,000 coal-fired steam plant on Jervois Quay, supplying "white coal" to power the tramcar fleet.[71][66]

On 29 October 1902, the first tracks were laid by an army of up to 300 unskilled labourers, often referred to as "navvies", who were paid a shilling an hour. They tore up city streets and laid rails, inserting squares of Australian hardwood, specifically jarrah, were placed to soak in tar.[72] The work was demanding, with long hours; the men started at 4:00 AM and finished at 11:00 PM.[72] By January 1904, the first ten tramcars had arrived from England.[73]

Men who would run the then-new electric trams for the city were provided uniforms that included a cap, overcoat, oilskin, tunic, trousers, and leggings, costing the Tramways Department £NZ1,000 per year to outfit them all.[63]

The first trial run of the electric tram took place on the evening of 8 June 1904. A double-decker tram moved down Riddiford Street and Adelaide Road before returning to the tram shed, while residents opened their doors and windows to watch the tram pass by.[74] The first public run occurred from Newtown to the Basin Reserve on 30 June 1904.[75] [76] Weeks after the electric trams began operating, the horse tram service was retired.[77] In 1904, the City Council decided to clear out and sell all horses, tramcars, equipment, and anything else used in the old horse-drawn tram service to the public.[78]

Expansion

[edit]

In 1904, extensions were made to Courtenay Place, Cuba and Wallace Street, Aro Street, Oriental Bay, and Tinakori Road.[79] The following year, a line was constructed through Newtown and Berhampore to Island Bay, and the year after, from the Te Aro line to Brooklyn.[80]

In 1904, the City Council's engineer recommended building a tram tunnel through Mount Victoria to Hataitai, extending as far as Kilbirnie.[81] A double-track tunnel was initially proposed, but this plan was never implemented.[82] The final design for the single-track tunnel would measure 1,273 feet in length, with a height of 17 feet 6 inches and a width of 12 feet at the base and was to include laying an 8-inch water supply main from the city to Kilbirnie through the tunnel.[83][84] Notably, it does not have a pedestrian walkway and the City Council would fine £5 for anyone trespassing in the tunnel.[85]

Construction of the tunnel began in October 1905, with the first sod turned by Wellington Mayor Thomas William Hislop on 18 October at Kilbirnie with Prime Minister Richard Seddon, who also attended the ceremony.[86] Work progressed on the Pirie Street side a week later with both teams meeting in the middle of 17 May that year.[87][88] Following this, work commenced on enlarging the tunnel and bricking the walls in July.[89] During the very last weeks before completion, a partial collapse of the earth killed three men.[90] The Hataitai tunnel cost £NZ70,000, it took over a year to complete, and involved a hundred miners working in three shifts, 25 bricklayers and apprentices, as well as teams of drivers and truckers to remove the spoil.[91][92]

The first trial run of a tram through the tunnel occurred on 12 April 1907, and passenger services officially started a few days later, on 16 April. This enabled the extension of the tramway service to Kilbirnie, Miramar, and Seatoun.[91] In December 1907, the Seatoun tunnel was open, is 470 feet in length and 27 feet in width.[93] When the trams arrived at Seatoun, it ended the ferries services there.[94]

In 1907, the Tinakori Road line was extended westward towards Karori, reaching Karori Cemetery.[95] In February 1911, the line to Karori was extended up Church Hill to Karori Park.[96] The City boundary was at the Wellington Botanic Garden in Tinakori Road and the Karori Borough Council was responsible past the Gardens. As with the Melrose Borough Council in 1903, the one council's operation of the city tramways was a factor in the amalgamation of Karori Borough Council with the Wellington City Council in 1920[97]

Construction of the new track then slowed but did not stop. In 1909, a line was built from Kilbirnie to Lyall Bay and another from Tinakori Road to Wadestown in 1911.[98][99] By 1910, the tram tracks extended for 35.5km, with nearly a third being double-tracked.[77]In April 1914, the Newtown tram line was extended beyond the tram barns to the Newtown Park Zoo.[100] In 1915, a line was built to connect Newtown with Kilbirnie via Constable Street and Crawford Road.[101] In 1911, two tramcars were constructed by the Tramways Department for freight and parcel services between the city and the suburbs, and depots were established throughout the city.[102] The freight trams transported various commodities, including food, coal, beer, and passengers' suitcases from the trains.[103]

Heyday

[edit]| FY | Patronage | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1882 | 3,000,000 | — |

| 1910 | 22,000,000 | +7.38% |

| 1930 | 46,581,456 | +3.82% |

| 1934 | 34,800,000 | −7.03% |

| 1939 | 44,000,000 | +4.80% |

| 1940 | 48,200,000 | +9.55% |

| 1943 | 62,000,000 | +8.75% |

| 1947 | 55,781,282 | −2.61% |

| 1965 | 0 | −100.00% |

| Source: 1882,[104] 1910,[105] 1930, 1934, 1939-1940,[106] 1943,[5] 1947[107] | ||

Many of Wellington's suburb were once remote, semi-rural areas with small populations. However, their development and growth significantly improved after the introduction of trams that connected these suburbs to the city.[108] For instance, Brooklyn and Wadestown did not expand considerably until the tramways were opened, which conquered the steep slopes and made these areas more accessible and attractive places to live.[109] Along tram routes, development driven by residential speculators flourished, with the proximity to the tram being a crucial factor in determining housing intensity.[110] The introduction of trams to the outer city also significantly transformed the social life of the residents. A new focus on leisure for the urban worker who could take a tram out to Lyall Bay to swim, sunbathe, take a seaside stroll or have picnics on their days off.[111]

When not in service, the trams were stored at several depots: Kilbirnie, Newtown, Thorndon, Chaffers Street, and Karori, where maintenance staff inspected and serviced them.[112] The tramway workers took great pride in their organisation. They formed rugby, cricket, and tennis teams and held picnics and dances. The Tramway Band was well-known throughout Wellington, and they played at local events.[94]

In 1924, a case went to the Court of Appeal of New Zealand challenging the use of eminent domain to secure right-of-ways for tracks. In Boyd v Mayor of Wellington, the court found that, although the government forced the sale of land improperly, it had acted in good faith so the sale was not reversed.[113]

On 4 June 1929, the last new line was completed, a branch of the Karori line through a tunnel to Northland.[114] The suburban tram system extensions has cost the City Council £NZ1,500,000 from 1905 to 1929.[104]

On 22 November 1933, the Fiducia tram was unveiled to the public during the New Zealand National Confidence Carnival to raise money for the Mayor's distress fund.[32][115] Fiducia is a Latin word that means "trust" or "confidence".[115] A 1935 demonstration by a Fiducia tram convinced the speaker and members of the Legislative Council that modern trams were silent.[116] The Fiducia tram was introduced to the streets of Wellington in 1937.[117] From 1935 to 1952, a total of 28 Fiducia trams were built at the Kilbirnie Workshop. In total, 274 trams were constructed: 14 were horse-drawn, 260 were electric passenger trams, and 2 were for freight transport.[118][48] The Fiducia model was the last to be constructed in New Zealand and the final one to operate during the last year of tram services.[117]

Finally, in 1940, a shorter route was opened up Bowen Street to the western suburbs of Karori and Northland instead of the route via Tinakori Road.[119] This had been proposed since 1907 and 1912, but successive prime ministers (Ward and Massey) opposed noisy trams using Bowen Street or Hill Street close to parliament.[120][121]

The war years

[edit]

During World War 2, women helped to address labor shortages in Wellington but faced challenges. In mid-1941, Wellington's City Council encountered a shortage of conductors, with passengers being left at stops while overcrowded trams passed by.[122] The council considered employing women as conductors but preferred to avoid additional costs for restrooms by having male conductors work overtime during peak hours.[122] However, some councillors questioned the delay in hiring women, and Mrs. Knox Gilmer argued that women would not require elaborate restroom facilities.[122]

In 1941, the Tramways Department hired its first "tram girls," providing them with uniforms consisting of navy serge peaked caps adorned with a badge, double-breasted greatcoats, trousers, and "battledress" tops modelled after army's uniforms at the time.[123][124] Notably, only women in Wellington were permitted to wear trousers.[125] Provincial candidates were required to be tall, slim, and strong to reach bells and navigate crowds, with some being rejected due to their short or wide stature.[126] The women worked alongside men on equal pay, both earning £5 0s 6d for a 40-hour week, with additional pay for overtime or broken shifts could add a pound or two.[127]

By 1944, there were 175 women conductors, accounting for nearly a third of the total Tramways staff but the Department wanted 200, and an inspector went to New Plymouth, Whanganui and Napier to interview recruits.[124][126] Competition among different offices led to many women being recruited as "conductorettes."[124] Women performed the cleaning of trams at night at the depot and were responsible for clipping tickets.[124] But women were not accepted as drivers of trams, because of heavy work on hill routes nor were they allowed to repair the rails.[126] Repairs and upgrades were limited due to wartime shortages, leading to the deterioration of tram tracks.[128][129] The road surface around the rails broke down because of vibrations, and during wet weather, increasingly large puddles formed, creating squelching sounds as each tram passed. These conditions eroded the foundations of the rails.[129]

In July 1943, an advertisement sought women aged 25 to 40 to do men's work, both full-time and part-time. Although the Wellington City Council Works Committee assured applicants that they would not be involved in heavy labor, like lifting or digging up rails, they would instead be responsible for tasks such as sealing and tamping.[129] An engineer from the Department made a statement regarding the employment of women on the tram track maintenance. He said, "I do not like the idea of women being employed in this work... it would benefit the Tramways Department to hire men instead, as they would be better suited for tamping down the asphalt."[130]

By August of that year, the first women's "pothole gang" began their work. They repaired the rough tarseal holes beside the tram tracks.[131] One member drove a small truck, while the others took turns filling the holes with metal chips, pouring tar, and tamping down the patches while being supervised by workmen.[131]

The women worked for less than a week on tram track maintenance. On August 20, the Minister of Industrial Manpower Angus McLagan who bowed to political pressure issued an order prohibiting the employment of women's in this role.[131][132] Mayor of Wellington Thomas Hislop expressed his astonishment, commenting on the government's mismanagement of manpower.[129][133] It was agreed on 21 August that the women would be diverted to more suitable occupations.[129] Enough men were assigned to manage the repairs of tram tracks. These repairs became a priority, with 70 men, including some ex-3rd Division soldiers, directed to the task during 1944.[129]

During the war years, the trams experienced their busiest period ever, as commuting American servicemen and petrol rationing drove passenger numbers close to 63 million in 1944.[128] To accommodate more passengers, the centre seats in the tram were removed, creating space for an additional 10 people.[123][128] The war years had shown that New Zealanders' lives continued almost without needing a car.[134]

Demise

[edit]Abandonment

[edit]

In 1925, the tram freight and parcel services were discontinued because of competition from motor vehicles.[102] One of the freight trams was scrapped in 1955, and the other was converted into a track grinder in the 1920s and withdrawn from service with the closing of the system in 1964.[135][136] In early 1945, after reviewing the report from the General Manager of the Transport and Electricity Departments, the City Council announced plans to convert one of the tram routes to single-operator trolleybuses.[137][128][119] The route selected was between the Railway Station and Oriental Bay, with extensions to Roseneath and Hataitai at one end, and to Aotea Quay at the northern end.[138] Ten trolleybus chassis and overhead equipment were ordered from Britain.[138] The first of these vehicles to be put into service on the Roseneath route was in June 1949.[138]

It was decided to replace the trams with buses and trolleybuses, as they were considered more advanced and better suited to the city's needs.[7] Several factors influenced this decision, including Wellington's challenging topography, the decline in passenger numbers after World War II, and the rise of operational costs of maintaining and purchasing trams and track renewals.[139][140][106] Additionally, the lack of track maintenance during the war meant that the capital expenditure required to bring the tracks up to standard far exceeded the cost of purchasing replacement buses, even though buses generally have a much shorter lifespan.[141]

The city's streets are often steep, winding, and narrow, making the greater manoeuvrability of buses a significant advantage. Some city councillors said that trams were uncomfortable and slow and that the necessary spare parts were no longer being manufactured.[142] However, Bob Stott of Rails highlighted that European trams were both fast and comfortable, and that spare parts for them were still available, yet these options were overlooked by the City Council.[142] After World War II, trams were increasingly viewed as outdated. Meanwhile, cars and buses were seen as the future for Wellington. [142]

In 1948, the City Council determined that improved access to Wadestown was necessary.[106] To implement this plan, the council decided to discontinue the tram service and replace it with diesel buses until the new roads were completed, which would then accommodate cars and trolleybuses that were on order.[106] This change would allow for the tram right-of-way to be widened and paved for bus and car use.[143] On 9 September 1953, the City Council announced that the Northland trams would be converted to buses from 21 September. However, a week later the announced decision was rescinded because the City Council had not obtained the necessary Order in Council from the Ministry of Works. It delayed the conversion, but by 17 September 1954 it made the Northland trams the shortest-lived service for the city.[144]

Saul Goldsmith started a campaign called "Save the trams" in 1959.[145] Campaigners for the movement made a proposed to retain the line from the railway station to Courtenay Place.[146] The City Council passed a resolution to raise a loan of £NZ1,282,230 to complete the transition to buses. Goldsmith successfully petitioned to hold a referendum on the loan issue.[147] On 22 June 1960, the poll passed, approving the City Council's proposal to borrow the funds necessary for converting the trams to buses.[48][148] By 1961, only 65 trams remained in service, down from a total of 155 that had been operational in April 1956.[149] In the 1962 Wellington City mayoral election, Goldsmith stood for the retention of what remained of the Wellington tramway system.[150] That same year, a petition was submitted to the City Council to retain the Hataitai service.[151]

Closure

[edit]

The first major line closure came in 1949 when Wadestown closed the first of a long series of tram routes to abandon.[152] The following year, the Oriental Bay line closed, with about 500 people who bid farewell to the last tram.[153][154] In 1954, the Karori line (including the Northland branch) closed. In 1956, after the last tram run in Auckland, Wellington became the last regular passenger service in New Zealand.[155] In 1957 services to Aro Street and Brooklyn ended. The construction of Wellington International Airport destroyed the route to Miramar and Seatoun.[156] All services to the eastern suburbs had ceased by 1962, with Lyall Bay closing in 1960,[157] Constable St/Crawford Rd in 1961, and Hataitai in 1962.[106] The Hataitai tunnel was closed for 11 months to be converted for the trolley buses.[106] On 17 January 1963, the City Council applied to Governor-General Bernard Fergusson for authorisation to abandon the use of trams and dismantle the tracks.[158] In 1963, the service to Island Bay was withdrawn, leaving mainly inner-city routes. By 31 March 1964, only 14.4 km of tracks were used by the trams down from 20km from the previous year.[159]

On 2 May 1964, the remaining tram line was officially closed with a parade that travelled from Thorndon to Newtown. Twelve trams operated during the service that morning, including three decorated trams in the final procession.[156][160] Hundreds gathered to witness the final three trams traverse the streets, and photographers recorded the occasion on cameras and film.[147][52][161]

The first two trams were adorned with red, white, and blue bunting, representing the colours of the New Zeland flag.[151] Wellington's and New Zealand's last tram was uniquely decorated in black and gold, the colours of Wellington.[146] It featured a large rosette on both the front and back, showcasing the city's coat of arms, surrounded by an arc of flags.[151] Slogans were written on the sides of all three trams.[151] The tram convoy was surrounded by Wellington residents listening to farewell speeches before they departed for the last time.[162] Those who could not get souvenir tickets for the last three trams clung on to the side of the trams till shaken off, or jogged, rode a bike along beside the tracks.[163] The last ride took 50 minutes instead of the usual 23 minutes.[163] All along the route people lined the streets, climbing on banks and hoardings, perching on buildings and fences, hanging out of windows and following in cars.[163]

During a closing ceremony at Thorndon, Mayor Frank Kitts expressed his belief that the decision to discontinue trams was as a "retrograde step."[164] However, Councillor Manthel, who was responsible for the changeover and a car dealer, viewed it as a successful conclusion.[147][165] In June 1960, he had stated that "trams caused difficulties in traffic and pedestrian control."[147] Goldsmith was interview after the closing ceremony and said "But just you wait and see the trams will be back again."[166] From 1954 to 1964 the City Council spent more than £NZ2,500,000 to remove the trams from Wellington.[166] After the closure of the service, the City Council announced a policy allowing the purchase of any trams at a scrap value of £22 10s each and that the buyer also arrange transport for the trams.[167] However, most of the trams were transported to Happy Valley were they were stripped of salvageable parts then intentionally set on fire, and the metal was later processed as scrap.[168][169] The principle of electric transport was maintained; many of the former tram routes continued to be served by trolleybuses until 2017.[170]

Removal

[edit]

On 16 September 1964, the City Council adopted a report regarding removing the old tram tracks. At that time, approximately 51.50km of track remained in the city and the surrounding suburban streets.[171] The City Council decided to remove the rail head and then pave over the area to avoid digging up the parts of the rail set in concrete.[172] The estimated cost for the work was NZ$1.1 million, and it was anticipated that the project could be completed within three years.[171] After the close of the tram services the tram poles were to gradually removed.[173]

The City Council had until 25 March 1966 to remove the remaining tram tracks or to obtain an extension from the Minister of Works.[174] However, after the paving work was completed on Willis Street, surface cracking occurred, indicating that the remaining tracks needed to be removed and repaved. [175]

In August 1964, Goldsmith attempted to prevent the City Council from sealing over the tram tracks between the Railway Station and Courtenay Place, hoping to keep them available for future tram use.[176][177] A meeting was held in September, and the City Council ultimately decided to proceed with the removal of the tracks.[178] The tracks under the road would be removed progressively over the years as road upgrades occurred.[179] The last known segments of the track were removed in 2010 in Manners Mall during roadworks.[180]

Post-closure: 1965-present

[edit]Queen Elizabeth Park Tramway

[edit]

Some of Wellington's old trams have been preserved. They are now in operation at the Wellington Tramway Museum at Queen Elizabeth Park in Paekākāriki on the Kāpiti Coast. The museum maintains nearly 2 km (1.2 mi) of 4-foot (1219mm) gauge track.[181][182]

Proposed systems

[edit]Proposed to lay down tracks for a Tram system for the region dates back to 1900. When Thomas Wilford advocated for a tramway from Petone to Taitā.[183] The boroughs of Petone and Lower Hutt took steps in 1904 to explore the possibility of an electric tramway. They formed a tramway board, then they made plans for a line along Jackson Street, which would serve as a feeder to and from the Petone railway station.[184] However, interest from the neighbouring borough led to a proposal for a combined tramway system.[184] In 1905, the Hutt Valley Tramway Board received a proposal from Tommy Taylor to install tramways, and the Wellington Meat Company would supply electricity for the system.[184] The Hutt Valley tramway could serve as a mixed goods route, according to a 1909 proposal.[185] The tramway board proposed to take a loan of £NZ80,000 to build the tramway but needed the ratepayers to head to a poll and vote for its approval.[186] Ultimately, a poll of ratepayers rejected the scheme.[184]

Occasionally, it has been suggested that trams should return to Wellington, either in a modern form or as a historical display. As early as 1979, converting the Johnsonville Railway line to a tram operation was suggested.[187] Several individuals and community groups were submitting suggestions to the Wellington Regional Council and City Councils, highlighting the potential of light rail transit in light of revival in North America and Europe during the 1980s.[188]

The most detailed and publicised effort by civil society to promote rail access was Transport 2000's 'Superlink' proposal, introduced in 1992 through booklets and pamphlets.[188] The 'Superlink' plan proposed converting the Johnsonville line to light rail and extending the system to the Airport and Karori via a tunnel from Holloway Road in Aro Valley to Appleton Park, it won the endorsement of many locals and some politicians.[189] The next year, the Regional Council, announced a light rail plan which was also welcomed by the city.[190] In 1995, a joint study commissioned by the City and Regional Councils called the Works/MVA report of 1995 proposed a light rail route that would run from the Wellington Railway Station along the "Golden Mile" to Courtenay Place. This proposal suggested that the light rail would extend all suburban rail lines, sharing tracks with heavy rail.[191]

An associated plan by the City Council that almost succeeded was a heritage tramway, similar to Christchurch, looping through the developing waterfront area and sharing light rail tracks along the "Golden Mile."[192] A 2.2 km route was proposed to be constructed in two stages, with a total estimated cost of NZ$6.7 million.[193] The first stage of the heritage tramway was projected to cost NZ$3 million.[194] The plan was to complete the first stage of the heritage tramway by September 1995 and would have used two trams to run every 10 minutes, and the Wellington Tramway Museum would supply the trams.[195] In the second stage, two more trams were to be provided for service; they were to be imported from Hong Kong.[196] Some track foundation work was done in 1995.[197] That was the last of that activity as the plan was ultimately scrapped.[198]

More recently, following the 2010 mayoral elections, Mayor Celia Wade-Brown pledged to investigate light rail between Wellington station and the airport.[199][200] In August 2017 the Green Party updated its transport policy to introduce light rail from the city centre to Newtown by 2025 and the airport by 2027.[201] Mayor Justin Lester reaffirmed his support for light rail along the "Golden Mile" in 2018.[202] In 2022, a proposal for a light rail line running from the Wellington city centre to Courtenay Place, then past the Wellington Hospital to the south coast at Island Bay, was part of Let's Get Wellington Moving. In mid-December 2023, the Minister of Transport, Simeon Brown, ordered the New Zealand Transport Agency to cease funding.[203]

Remnants

[edit]

Some of Wellington's old trams have been preserved, and are now in operation at the Wellington Tramway Museum at Queen Elizabeth Park in Paekākāriki on the Kāpiti Coast and at the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland.[204]

Around the city, it is still possible to see buildings associated with the system. The most prominent and largest remaining sites are the Kilbirnie workshops, although the land area has gradually decreased. A retirement village has now replaced what used to be a large outdoor storage yard. However, the major brick structures from the former Tram workshops remain largely unchanged.[198]

The Tramway Hotel on Adelaide Road opened soon after the tram service began.[205] It is located at the end of the original tram line.[206] Nearby is Brown Street, named after Samuel Brown, the contractor who laid the original track.[206] There is the old tramway office opposite the Lambton Quay entrance to the Railway Station.[206]

The Taj Mahal is a building located on the median strip between Kent and Cambridge Terraces and Courtenay Place and Wakefield Street. It was constructed in 1928 and opened in July 1929 as public toilets for tram passengers.[207]

Tram return loops are located near the Newtown Park Zoo and one in Miramar.[198] Several weather shelters can be found scattered around the city, including one at the Newtown Park Zoo loop and others in Wadestown, Miramar, and Oriental Bay.[208] Additionally, there is a former Tram Office that once served as the booking office for the Tramways Department.[209] On the corner of Wakefield Street and Jervois Quay is the last known remaining tram pole in Wellington to remain in situ and the only one to in New Zealand to retain the brackets to which the overhead wires were attached.[210]

In 2024, the city council laid historic tram tracks on the Parade in Island Bay as a part of a village upgrade to represent when trams ran along The Parade.[211][212] The Wellington Tramway Museum had agreed to provide two ten-meter-long rails for the street display on The Parade. The museum prepared the rails, trimming them to the required length, drilling holes, fitting tie bars, cleaning rust, and painting the rail tops. An interpretation panel was set up to explain the history of trams in the suburb.[213]

List of dates

[edit]The years of opening and closing of various tram routes are:[214]

| Route | Opened | Closed | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aro Street | 1904 | 1957 | |

| Brooklyn | 1906 | 1957 | |

| Hataitai | 1907 | 1962 | |

| Hataitai/Kilbirnie/Miramar | 1907 | 1957 | via Hataitai tram tunnel |

| Island Bay | 1905 | 1963 | |

| Karori | 1907 | 1954 | |

| Kilbirnie | 1915 | 1961 | via Crawford Road |

| Lyall Bay | 1911 | 1960 | |

| Newtown/Thorndon | 1904 | 1964 | |

| Northland | 1929 | 1954 | branch of Karori route |

| Oriental Bay | 1904 | 1950 | |

| Seatoun | 1907 | 1958 | |

| Tinakori Road | 1904 | 1949 | extended to Karori |

| Wadestown | 1911 | 1949 |

In popular culture

[edit]The 1992 comedy splatter film Braindead features several shots of trams, overhead wires, and model tramlines.[215][216] The production designers created a miniature to reproduce the Newtown tramway for the film.[217] Many artists and illustrators have created works depicting the tramways, including murals in the Wellington suburbs of Oriental Bay and Kilbirnie, as well as oil paintings by William Stewart that capture impressions of the steam and electric trams.[218][219][220]

See also

[edit]- Trams in New Zealand

- Christchurch tramway system

- Light rail in Auckland

- Public transport in the Wellington Region

- Public transport in New Zealand

References

[edit]Notes

Citations

- ^ Lawes 1964, p. 21.

- ^ Railway World 1905, p. 1.

- ^ "Tramways Department". Archives Online. Wellington City Council. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ Owen 1994, p. 14.

- ^ a b McLeod & Farland 1970, p. 189.

- ^ "Trams in Wellington, 1878-1964". Wellington City Libraries. Wellington City Council. Archived from the original on 11 August 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Ngā Kā Rēra i Te Whanganui-a-Tara, 1878-1964 Trams in Wellington, 1878-1964". Wellington City Libraries. 2022. Archived from the original on 27 November 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Kelly 1996, p. 58.

- ^ "Volume XXXIII, Issue 5432". New Zealand Times. 24 August 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "LOCAL & GENERAL, Volume XVI, Issue 1217". Wairarapa Standard. 28 January 1882. p. 2. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "THE WELLINGTON TRAMWAY COMPANY, Volume XLI, Issue 7009". New Zealand Times. 8 November 1883. p. 2. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand's last electric tram trip". New Zealand History. 5 November 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Electric tram in Island Bay". Wellington City Recollect. Archived from the original on 9 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Kapiti Line (Waikanae – Wellington) – Metlink". www.metlink.org.nz. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "Johnsonville Line (Wellington-Johnsonville) Metlink". www.metlink.org.nz. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Ward 1928, p. 243.

- ^ "Wellington Cable Car". WellingtonNZ. Archived from the original on 30 December 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ "Cable Car HISTORY". Wellington Cable Car. Archived from the original on 8 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Cook, Stephen. "WELLINGTON TRAMWAY SYSTEM MAP". Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand's rail network". LEARNZ. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Tramways Act 1872 (36 Victoriae 1872 No 22)". NZLII. 25 October 1872. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "THE TRAMWAYS ACT, Issue 1096". Otago Witness. 30 November 1872. p. 1. Archived from the original on 15 December 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "STREET TRAMWAY, Volume XXVIII, Issue XXVIII". Wellington Independent. 18 February 1873. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d "THE WELLINGTON CITY STEAM TRAMWAYS, Issue 5264". Otago Daily Times. 1 January 1879. p. 1. Archived from the original on 15 December 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "WELLINGTON, Volume XIX, Issue 3101". Wanganui Chronicle. 30 June 1876. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "LATEST TELEGRAMS, Issue 2739". Star (Christchurch). 9 January 1877. p. 2. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d McDonnell 1978, p. 3.

- ^ a b McDonnell 1978, p. 2.

- ^ "FIFTY, NOT OUT!, Volume CVI, Issue 40". Evening Post. 25 August 1928. p. 17. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Wellington steam-tram service opened". New Zealand History. 27 July 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 232.

- ^ McGavin 1978, p. 5.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 11.

- ^ Stewart 1985, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Lawes 1964, p. 4.

- ^ Humphris, Adrian (11 March 2010). "Public transport - Horse and steam trams". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "Lambton Quay". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "WELLINGTON STEAM TRAMWAYS, Volume XVI, Issue 289". Evening Post. 6 December 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "RESIDENT MAGISTRATE'S COURT. THIS DAY, Volume XVI, Issue 273". Evening Post. 18 November 1878. p. 2. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ New Zealand, Archives (18 August 2016). "1879 Petition against Steam Trams". flickr. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 14.

- ^ Mulgan 1939, p. 209.

- ^ Stewart 1985, p. 15.

- ^ "THE TRAMWAYS COMPANY, Volume XVIII, Issue 150". Evening Post. 23 December 1879. p. 2. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "Page 3 Advertisements Column 1". Evening Post. 17 February 1880. p. 3. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "SALE OF THE TRAMWAY PLANT, Volume XIX, Issue 68". Evening Post. 24 March 1880. p. 2. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d Moffatt 2007.

- ^ McLeod & Farland 1970, p. 192.

- ^ a b Lawes 1964, p. 5.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 33.

- ^ a b Jardine, Trish (3 September 1977). "The days when trams trundled the streets". Evening Post.

- ^ "WELLINGTON TRAMWAYS, Issue 153". Auckland Star. 1 July 1887. p. 5. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "MUNICIPALISATION OF OUR TRAMWAYS, Volume LIX, Issue 128". Evening Post. 31 May 1900. p. 6. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Page 8 Advertisements Column 7, Volume LIX, Issue 129". Evening Post. 1 June 1900. p. 8. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "THE CITY TRAMWAYS. THE CORPORATION TAKES POSSESSION, Volume LX, Issue 79". Evening Post. 1 October 1900. p. 6. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Timeline - We Built This City". Archives Online. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "SOME CITY PROJECTS, Volume LXXI, Issue 4040". New Zealand Times. 3 May 1900. p. 4. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d Pringle 1965, p. 76.

- ^ Yska 2006, p. 38.

- ^ "LOAN CONSOLIDATION, Volume LXXII, Issue 4583". New Zealand Times. 11 February 1902. p. 5. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ Parliament 1902, p. 4.

- ^ a b Railway World 1905, p. 9.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 1.

- ^ "Re NZ Electrical Syndicate poles, Tramways Engineer". Wellington City Council Archives. 7 May 1903. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ a b Yska 2006, p. 104.

- ^ Irvine, Kerrigan & Cawte 2023, p. 4.

- ^ a b Irvine, Kerrigan & Cawte 2023, p. 12.

- ^ "Tramways Poles in the centre of streets". Archives Online. 1921–1926. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ Irvine, Kerrigan & Cawte 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Railway World 1905, p. 2.

- ^ a b Yska 2006, p. 105.

- ^ Yska 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Stewart 1985, p. 46.

- ^ Duncan, James; McAlpine, Christen (2021). "Tram No. 135 and its century of travelling the tracks". New Zealand: The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT). Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Parsons 2010, p. 177.

- ^ a b Yska 2006, p. 107.

- ^ "LOCAL AND GENERAL, Volume LXXVII, Issue 5375". New Zealand Times. 7 September 1904. p. 4. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 35,201.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 42.

- ^ "Tramway extensions into the suburbs". Evening Post. Vol. LXVII, no. 51. 1 March 1904. p. 2. Retrieved 8 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ "Electric Tramways". New Zealand Times. Vol. LXXI, no. 4306. 15 March 1901. p. 7. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ "The Kilbirnie Tunnel". New Zealand Times. Vol. XXIX, no. 6120. 29 January 1907. p. 4. Archived from the original on 9 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ "The new city loan". New Zealand Times. Vol. LXXVII, no. 5512. 14 February 1905. p. 7. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ "Wellington City Council". New Zealand Times. Vol. XXIX, no. 6247. 28 June 1907. p. 8. Archived from the original on 9 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ Humphris, Adrian (11 March 2010). "Wellington tram tunnel". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 17 June 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Local and general". Evening Post. Vol. LXX, no. 95. 19 October 1905. p. 4. Archived from the original on 9 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ "Local and general". New Zealand Times. Vol. XXVII, no. 5731. 28 October 1905. p. 4. Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ "Under Mount Victoria". New Zealand Times. Vol. XXVIII, no. 5897. 12 May 1906. p. 9. Archived from the original on 9 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ "Accidents and fatalities". Ashburton Guardian. Vol. XXII, no. 7120. 23 February 1907. p. 2. Archived from the original on 9 August 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via PapersPast.

- ^ a b Lawes 1964, p. 12.

- ^ Yska 2006, p. 109.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 49.

- ^ a b McDonnell 1978, p. 6.

- ^ "THEN. AND NOW, Volume 1, Issue 7". Dominion. 3 October 1907. p. 4. Archived from the original on 9 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Taylor, James (6 June 2006). "Glendaruel 316 Karori Road, Karori, WELLINGTON". New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Archived from the original on 7 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Patrick 1990, p. 40, 41, 50.

- ^ "BY TRAM TO LYALL BAY, Volume LXXVIII, Issue 145". Evening Post. 16 December 1909. p. 7. Archived from the original on 8 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 52.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Efford, Brent (26 August 2017). "Welcome and sensible: the Greens' plan for light rail". Wellington.Scoop. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b Lawes 1964, p. 18.

- ^ Stewart 1985, p. 68.

- ^ a b Mulgan 1939, p. 210.

- ^ Yska 2006, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e f McGavin 1978, p. 21.

- ^ Wood 1950, p. 287.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 1, 42.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 51-52.

- ^ Miskell 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Yska 2006, p. 111.

- ^ Pringle 1965, p. 79-80.

- ^ Scott, Struan (1999). "INDEFEASIBILITY OF TITLE AND THE REGISTRAR'S 'UNWELCOME' S81 POWERS". NZLII. Archived from the original on 17 December 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "The Opening of a "Famous" Tunnel in New Zealand". Transportation History. 4 June 2020. Archived from the original on 7 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b Stewart 1985, p. 95.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 168.

- ^ a b Owen 1994, p. 13.

- ^ McGavin 1978, p. 19.

- ^ a b Owen 1994, p. 2.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 188.

- ^ McGavin 1978, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1986, p. 1082.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d Yska 2006, p. 162.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1986, p. 1084.

- ^ Taylor 1986, p. 1083.

- ^ a b c d Yska 2006, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor 1986, p. 1085.

- ^ "WOMEN TURN TO TRAM TRACK REPAIRS, Volume CXXXVI, Issue 43". Evening Post. 19 August 1943. p. 6.

- ^ a b c Stewart 1973, p. 193.

- ^ "BANNED WOMEN GANGERS TRACK MAINTENANCE, Volume CXXXVI, Issue 44". Evening Post. 20 August 1943. p. 3. Archived from the original on 24 January 2025. Retrieved 19 January 2025.

- ^ "MAYOR ASTOUNDED, Volume CXXXVI, Issue 44". Evening Post. 20 August 1943. p. 3. Archived from the original on 24 January 2025. Retrieved 19 January 2025.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 192.

- ^ McGavin 1978, p. 18.

- ^ Owen 1994, p. 9.

- ^ Pringle 1965, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Pringle 1965, p. 79.

- ^ "General News". Press. 6 April 1961. p. 14. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ "TRANSPORT LOSS IN WELLINGTON, Volume C, Issue 29591". Press. 14 August 1961. p. 13. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Bellamy & Stott 1974, p. 4.

- ^ Lawes 1964, p. 24.

- ^ Lawes 1964, p. 14.

- ^ "Last Trip For N.Z.'s Last Tram, Volume CIII, Issue 3043". Press. 4 May 1964. p. 3. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ a b Stewart 1973, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d McLeod & Farland 1970, p. 194.

- ^ "General News". Press. 23 June 1960. p. 14. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Lawes 1964, p. 32.

- ^ Traue, James Edward, ed. (1978). Who's Who in New Zealand, 1978 (11th ed.). Wellington: Reed Publishing. p. 124.

- ^ a b c d Lawes 1964, p. 33.

- ^ City Council 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 215.

- ^ City Council 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Stewart 1985, p. 108.

- ^ a b McGavin 1978, p. 24.

- ^ "CHANGEOVER TO BUSES". Press. 1 August 1960. p. 10. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Archives 1970, p. 52.

- ^ Owen 1965, p. 346.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 2.

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 124.

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 123.

- ^ a b c "Cheers, tears follow trams to obscurity". The Dominion. 4 May 1964. p. 2.

- ^ Yska 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Yska 2006, p. 181.

- ^ a b "Trams will return, he declares". Evening Post. 2 May 1964.

- ^ Stewart 1973, p. 227-228.

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 126.

- ^ New Zealand 2022, p. 2.

- ^ Budach, Dirk (31 October 2019). "New Zealand: 56 modern trolleybuses out of service for 2 years now". Urban Transport Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ a b Archives 1970, p. 2.

- ^ "Removal of tramlines is defended". Evening Post. 8 January 1970.

- ^ Irvine, Kerrigan & Cawte 2023, p. 16.

- ^ Archives 1970, p. 30.

- ^ "Willis Street lines to be uprooted". Dominion. 6 January 1970.

- ^ Archives 1970, p. 33.

- ^ "Wants tracks for trams left until election". Evening Post. 24 August 1964.

- ^ Archives 1970, p. 31.

- ^ Archives 1970, p. 32.

- ^ one, kegan (5 October 2010). "Old tram lines". flickr. Archived from the original on 12 January 2025. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ "Trams and Tramway Museum". Greater Wellington Regional Council. 8 December 2021. Archived from the original on 5 January 2025. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ Efford 2018, p. 42.

- ^ "DISSOLVED, Volume LXXXIII, Issue 23". Evening Post. 27 January 1912. p. 11. Archived from the original on 23 January 2025. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d Stewart 1973, p. 101.

- ^ "HUTT VALLEY TRAMWAYS, Volume 2, Issue 436". Dominion. 19 February 1909. p. 7. Archived from the original on 23 January 2025. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "HUTT VALLEY TRAMWAY BOARD, Volume LXXVIII, Issue 119". Evening Post. 16 November 1909. p. 2. Archived from the original on 4 January 2025. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Efford 2018, p. 48.

- ^ a b Efford 2018, p. 49.

- ^ Efford 2018, p. 49-50.

- ^ Efford 2018, p. 51.

- ^ Efford 2018, p. 52.

- ^ Efford 2018, p. 54.

- ^ Douglas 1993, p. 4.

- ^ "Trams smart thinking". Evening Post. 10 May 1994.

- ^ Zatorski, Lidia (6 March 1994). "Tram plan on track for next year". Evening Post.

- ^ Douglas 1993, p. 4, 24.

- ^ Buckman, Sam (19 October 1995). "Work starts on square revamp". Evening Post.

- ^ a b c Cook, Stephen. "Wellington Tramway Remnants". Marklin. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ Nichols, Lane (18 October 2010). "Just how green will we go under Celia?". The Dominion Post. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "New mayor's dream ride". The Dominion Post. 1 November 2010. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Greens plan light rail to Wellington Airport by 2027". 24 August 2017.

- ^ Develin, Collette; Damian George (4 April 2018). "'Strong likelihood' of billion-dollar light rail system for Wellington, says mayor". The Dominion Post. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Coughlan, Thomas. "Government and councils agree to kill $7.4b Wellington transport plan". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 3 December 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Tram [No. 47 (Double Decker)]". MOTAT. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ Babington, Briar (3 September 2015). "Adelaide Rd's history of trams, earthquakes and murder". Stuff. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ a b c McDonnell 1978, p. 1.

- ^ Stewart 1999, p. 28.

- ^ City Council 2013, p. 1.

- ^ "Post Office Square, Wellington". National Library. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ Irvine, Kerrigan & Cawte 2023, p. 24.

- ^ "Island Bay Parade Safety Improvement and Upgrade" (PDF). Wellington City Council. 30 July 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Island Bay village upgrades". Wellington City Council. November 2024. Archived from the original on 8 December 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ Carter 2024, p. 171.

- ^ Parsons 2010, p. 193.

- ^ "Electric Trolleybuses in the Movies". Simon Fraser University. 2001. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ "Braindead". REELSTREETS. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ "Peter Jackson with the miniature set for the film Braindead - Photograph taken by Mark Coote". National Library. 1 February 1992. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ "Eastern suburbs Murals in suburbs from Hataitai to Strathmore". Wellington City Council. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Wong, Justin (7 July 2022). "Wellington mural adds splash of colour, history to Oriental Bay". Stuff. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ McQueen 1998, p. 8, 32.

Bibliography

Not by author; sorted by publication name

- Owen, David William (1994). A Ride Down Memory Lane: The Electric Tramcars that once served Wellington. Wellington: Wellington Tramway Museum Incorporated. p. 16. ISBN 0-958-22310-6. Archived from the original on 24 January 2025. Retrieved 20 January 2025.

- Stewart, Grantham (1999). Around Wellington by Tram in the 20th Century. Wellington: Grantham House Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 1869340728.

- Pringle, F. W. (1965). City of Wellington New Zealand Year Book 1962-1965. Wellington: Evening Post. p. 168. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2025.

- Ward, Louis E. (1928). Early Wellington. Auckland: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. p. 544. Archived from the original on 30 December 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- Patrick, Margaret G. (1990). From bush to suburb: Karori, 1840-1980. Wellington: Karori Historical Society. p. 72. ISBN 0-473-00915-3.

- Stewart, Graham (2006). From Rails to Rubber: The Downhill Ride of New Zealand Trams. Wellington: Grantham House Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 1-86934-100-7.

- Kelly, Michael (1996). Old Shoreline Heritage Trail (PDF). Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 69. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- Mulgan, Alan (1939). The City of the Strait: Wellington and its Province, a Centennial History. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed. p. 387. ISBN 978-0-908329-88-5.

- Stewart, Graham (1973). The End of the Penny Section: A History of Urban Transport in New Zealand. Wellington: Reed. p. 260. ISBN 0-589-00720-3.

- McDonnell, Hilda (1978). The First 100 Years: Wellington Centenary of Public Transport. Wellington: Wellington City Transport. p. 8. Archived from the original on 23 January 2025. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- Taylor, Nancy (1986). The New Zealand People At War - The Home Front Volume II. Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs. p. 1330. ISBN 0477012604.

- Miskell, Boffa (2013). Thematic Heritage Study of Wellington, January 2013. Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-877232-72-5.

- Wood, George (1950). The New Zealand official year-book, 1947-49. Wellington: New Zealand. Census and Statistics Department. p. 1048. ISSN 0078-0170. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- Owen, Roy (1965). The New Zealand official year-book 1965. Wellington: Department of Statistics. p. 1215. ISSN 0078-0170.

- Carter, Graeme (2024). The New Zealand Railway Observer October - November 2024 Volume 81, N०4. Wellington: The New Zealand Railway & Locomotive Society. p. 41. ISSN 0028-8624.

- Bellamy, Alan; Stott, Bob (1974). Twilight of Trams. Dunedin: Southern Press. p. 35.

- New Zealand, Vintage Car Club (2022). VCC HOROWHENUA SPARK OCT 2022. Levin: Vintage Car Club of New Zealand. p. 32. Archived from the original on 24 January 2025. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- Yska, Redmer (2006). Wellington: Biography of a City. Wellington: Reed Publishing Ltd in association with the Wellington City Council and the Ministry of Culture & Heritage. p. 300. ISBN 9780790011172. Archived from the original on 23 January 2025. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- McLeod, Norman; Farland, Bruce (1970). Wellington Prospect: Survey of a City, 1840 - 1970. Wellington: Hicks Smith & Sons Limited. p. 231. ISBN 0456005102. Archived from the original on 23 January 2025. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- Parsons, David (2010). Wellington's Railway: Colonial Steam to Matangi. Wellington: Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-908573-88-2. Archived from the original on 23 January 2025. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- Lawes, John William (1964). Wellington Tramway Memories. Wanganui: R. B. Alexander. p. 35. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- McGavin, T. A. (1978). Wellington Tramway Memories (3rd ed.). Petone: New Zealand Railway and Locomotive Society Incorporated. p. 29. ISBN 0-908573-22-7.

- Stewart, Graham (1985). When Trams were trumps in new zealand. Wellington: Grantham House Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-0869340004.

- McQueen, Euan (1998). W.W. Stewart 20th Century New Zealand Railway Painter. Wellington: Grantham House Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 1869340698.

- Online sources

- Moffatt, Graeme (director, writer) (2007). Back in Business (television documentary). New Zealand: Capital Video Productions Ltd. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Efford, Brent (2018). Direct through service tram-train for a complete rail system (PDF). Wellington: NZ Agent, Light Rail Transit Association PLC. p. 108. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2025. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- Irvine, Susan; Kerrigan, Carole-Lynne; Cawte, Hayden (2023). "Historic Heritage Evaluation" (PDF). Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 45.

- City Council, Wellington (2013). "Various bus and tram shelters". Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 21.

- Primary sources

- Railway World, Tramway (1905). The Tramway and Railway World A Review Of Current Progress In Electric And Other Traction Vol. XVIII. London: Tramway and Railway World. p. 9. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- Archives, Wellington City Council (1970). Tramways, Order-in-Council No. 27, removal of remaining tram tracks in Wellington, 1963, Town Clerk. Wellington: Wellington City Council. p. 73.

- Douglas, Neil (1993). Wellington Heritage Tramway Feasibility Study. Wellington: Douglas Economics. p. 57. ISBN 0-473-022-34-6.

- Parliament, New Zealand (1902). Wellington City Electric Tramway : Order in Council. Wellington: NZ Parliament. p. 10. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

External links

[edit]- Wellington Tramway Museum

- Vehicular Traffic (Carriages, Tramways etc) in Cyclopaedia of New Zealand Volume I (Wellington) of 1897

- Wellington Electric Tram 1904 on 1985 45c stanp

- Photo of horse tram on The Quay 1900

- Photo of woman tram conductor 1943

- "Photo of double saloon tram in front of Old Government Building". NZRLS. 2022.

- "Trams and Trolley buses at Wellington Railway Station (1963 photo)". National Library. 2022.

- "Horse Trams Cuba street, corner of Dixon St: 1885 (photo)". WCC Archives. 2024.