User:Seankaczanowski/sandbox

Fisherian or Fisher’s runaway, first proposed by R. A. Fisher in the early 20th century, is a hypothesized selection mechanism for the evolution of male ornamentation (secondary sexual characteristics), observed in numerous sexually reproducing species; based upon the attraction to ornamented males through female sexual selection (female choice).[1][2][3]

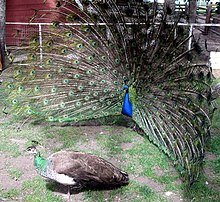

The evolution of male ornamentation, an example being the colourful and elaborate male peacock plumage compared to the relatively subdued female peahen plumage, represented a paradox for evolutionary biologists in the period following Darwin and leading up to the modern evolutionary synthesis; the selection for costly ornaments appearing incompatible with natural selection.[4][3][5][6] Fisherian runaway is an attempt to resolve this paradox, using an assumed genetic basis for both the preference and the ornament, through the not so obvious but powerful forces of sexual selection (a sub component of natural selection). Fisherian runaway hypothesizes that females choose “attractive” males with the most exaggerated ornaments based solely upon the males possession of that ornament. This female preference for ornamented males based upon possession alone can undermine natural selection by selecting for an ornament that may otherwise be non-adaptive and selected against in natural selection which results in male offspring more likely to possess the ornament and female offspring more likely to possess the preference for the ornament. Over subsequent generations this can lead to the runaway selection by means of a positive feedback mechanism for males who possess the most exaggerated ornaments (made possible through the genetic variability and heritability of both the ornament and the preference).[1][2][7][3]

Fisherian runaway sought to resolve the paradox of male ornamentation, but the mechanism (nor the secondary sexual characteristic or preference) is not restricted to these sexually reproducing systems. Fisherian runaway can be applied beyond ornaments to include sexually dimorphic traits and characters such as behaviour and structural displays expressed by either sex.[1][2]

Fisherian runaway has been difficult to demonstrate empirically, despite being theoretically plausible, due in part to the difficulty of detecting the genetic mechanism and the process by which it is initiated.[4][5]

Background

[edit]

Secondary sexual charcteristics and sexual dimorphism

[edit]Secondary sexual characteristics are characters or traits that are not directly apart of the reproductive system but serve to give an advantage to those who possess them over rivals either through intrasexual competition or intersexual courtship. Secondary sexual characteristics possessed and expressed in one sex (generally the male) and not the other results in a sexually dimorphic species; that is to say there is a difference in character or trait expression between the sexes (i.e. male ornamentation).[4][5]

Examples of sexually dimorphic secondary sexual characteristics

[edit]- Peacock plumage

- Lion manes

- Narwal tusks

- Deer antlers

- Birds of paradise plumage and courtship displays

- Swordtail tail fin length

- Songbird bird song

Historical context

[edit]R.A. Fisher, considered by many to be the greatest evolutionary biologist since Darwin, was a peer of Darwin’s son, Leonard, and much like Charles both were fascinated by the mechanics of sexual selection.[3][8]

“[of] the branches of biological science to which Charles Darwin’s life-work has given us the key, few, if any, are as attractive as the subject of Sexual Selection … ” Fisher, R.A. (1915) The evolution of sexual preference. Eugenics Review (7) 184:192[1]

Fisher’s romanticism towards sexual selection was not shared, however, by the vast majority of his peers in the early developments of the modern evolutionary synthesis. Darwin’s lengthy ode to sexual selection in the latter half of, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex[9] (1870) garnered interest upon its release but by the 1880’s the ideas had been deemed too controversial and largely neglected and ignored by biologists until the second half of the 20th century, with the notable exception of Fisher and a few others.[10][8]

Fisher first mused about the power of female choice and the force by which sexual selection could oppose or even undermine natural selection and give rise to sexual ornamentation in an impassioned objection to the remarks of Sir Alfred Wallace that animals show no sexual preference in the 1915 paper, The evolution of sexual preference.[1]

“The objection raised by Wallace … that animals do not show any preference for their mates on account of their beauty, and in particular that female birds do not choose the males with the finest plumage, always seemed to the writer a weak one; partly from our necessary ignorance of the motives from which wild animals choose between a number of suitors; partly because there remains no satisfactory explanation either of the remarkable secondary sexual characters themselves, or of their careful display in love-dances, or of the evident interest aroused by these antics in the female; and partly also because this objection is apparently associated with the doctrine put forward by Sir Alfred Wallace in the same book, that the artistic faculties in man belong to his “spiritual nature,” and therefore have come to him independently of his “animal nature” produced by natural selection.” Fisher, R.A. (1915) The evolution of sexual preference. Eugenics Review (7) 184:192[1]

Fisher, in the foundational 1930 book, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection[2], first outlined a model by which runaway inter-sexual selection could lead to sexually dimorphic male ornamentation based upon female choice and a preference for “attractive” but otherwise non-adaptive traits in male mates.

“[O]ccasions may not be infrequent when a sexual preference of a particular kind may confer a selective advantage, and therefore become established in the species. Whenever appreciable differences exist in a species, which are in fact correlated with selective advantage, there will be a tendency to select also those individuals of the opposite sex which most clearly discriminate the difference to be observed, and which most decidedly prefer the more advantageous type. Sexual preference originated in this way may or may not confer any direct advantage upon the individuals selected, and so hasten the effect of the Natural Selection in progress. It may therefore be far more widespread than the occurrence of striking secondary sexual characters.” Fisher, R.A. (1930) The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. ISBN 0-19-850440-3[2]

Explanation

[edit]Overview

[edit]‘’’Fisherian runaway’’’ is a hypothesized mechanism using inter-sexual selection for the evolution of sexually dimorphic secondary sexual characteristics (male ornamentation) that do not play a role in intra-sexual selection nor increase the fitness of the males who possess them in an obvious way.[1][2][11][12][13]

‘’’Fisherian runaway’’’ attempts to resolve the paradoxical evolution of seemingly non-adaptive male ornaments (secondary sexual characteristics) within the context of evolutionary theory. Originally hypothesized during the beginning of the modern evolutionary synthesis, Fisherian runaway suggests that male ornamentation is the result of a positive feedback (“runaway”) mechanism that is driven by intersexual selection and the preferences of females (known as female choice) for male ornaments that seem non-adaptive but are perceived as "attractive" through there possession alone. A strong female choice for the possession, as opposed to the function, of a male ornament can oppose and undermine the forces of natural selection and result in the runaway sexual selection for the further exaggeration of the ornament until the costs (via natural selection) of the ornament become greater than the benefit (via sexual selection).[1][2]

An example using the peacock/peahen sexual dimorphism

[edit]

The male peacock and the female peahen of the ‘’Pavo’’ genus represent a classic example of the type of sexually dimorphic male ornamentation that traditionally has appeared paradoxical in the context of natural selection. The peacock’s colourful and elaborate tail requires a great deal of energy to grow and maintain; it reduces the bird's agility, and it may increase the animal's visibility to predators and thus appears to lower the fitness of the individuals who possess it. Yet it has evolved, which indicates that peacocks with longer and more colourfully elaborate tails have some advantage over peacocks who don’t. Fisherian runaway posits that the evolution of the peacock tail is possible if peahens have a preference to mate with peacocks that possess a longer and more colourful tail. Peahens that do select males with these tails in turn have male offspring more likely to have long and colourful tails which themselves are more likely to be sexually successful themselves because of the preference for them by peahens. Furthermore the peahens who select males with longer and colourful tails are more likely to produce peahen offspring that have a preference for peacocks with longer and more colourful tails. Given this, having a preference for longer and more colorful tails bestows an advantage to peahens just as having a longer and more colorful tail does bestows an advantage upon peacocks.[1][2]

However, all members of the species are less fit than they would be if none of the peahens (or only a small number) had a preference for a longer or more colorful tail. In the absence of such a preference, the possession of these tails would be non-adaptive; reduced mobility and increased visibility to predators would no longer be incentivized by a sexual preference. The sexual preference of peahens to mate with peacocks who possess long and colourful tails in this case undermines the seemingly non-adaptiveness of these tails according to Fisherian runaway, giving rise to the sexually dimorphic peacocks and peahens of the ‘’Pavo’’ genus.[1][2]

Fundamental conditions

[edit]In order for the Fisherian runaway mechanism to lead to the evolution of male ornamentation, Fisher outlined two fundamental conditions that must be fulfilled: (i) sexual preference in atleast one of the sexes, and (ii) a corresponding reproductive advantage to the preference.[2]

Assumed genetic basis for sexual preference

[edit]For any hypothesis to be resolved within the context of evolutionary biology there must be a genetic basis.[14] In order for traits and characters to be passed along to offspring and in order for more exaggerated expressions to be sexually selected for, Fisherian runaway assumes that sexual preference in females and ornamentation in males is both genetically variable and heritable.[2][11]

Fisher eluded to this need for a genetic basis when outlining Fisherian runaway in the The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection (1930).

“If instead of regarding the existence of sexual preference as a basic fact to be established only by direct observation, we consider that the tastes of organisms … be regarded as the products of evolutionary change, governed by the relative advantage which such tastes may confer. Whenever appreciable differences exist in a species … there will be a tendency to select also those individuals of the opposite sex which most clearly discriminate the difference to be observed, and which most decidedly prefer the more advantageous type.” Fisher, R.A. (1930) The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. ISBN 0-19-850440-3[2]

Sexual selection, through female choice for ornamentation

[edit]Fisher argues that the selection for male ornamentation is through the sexual preference of females (female choice) who consider the ornament desirable or “attractive”. This choice by females makes the ornament advantageous in possession ‘’alone’’, even though outside of the selection of sexual preference the ornament may appear non-adaptive, especially in the light of natural selection as a whole. This sexual selection process of females choosing males to whom they find “attractive” can undermine the direction of natural selection, a key component to Fisherian runaway. [1][2][11][12][13]

“Certain remarkable consequences do, however, follow if some sexual preferences of this kind … are developed in a species in which the preferences of … the female, have a great influence on the number of offspring left by individual males. In such cases… an additional advantage conferred by female preference, which will be proportional to the intensity of the preference. The selective agencies other than sexual preference may be opposed to … yet … development will proceed, so long as the disadvantage is more than counterbalanced by the advantage in sexual selection … there will also be a net advantage in favour of giving to it a more decided preference.” Fisher, R.A. (1930) The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. ISBN 0-19-850440-3[2]

Positive feedback, sexy sons, choosey females and runaway selection

[edit]The fact that sexual preference based solely upon the possession of an “attractive” ornament can make the ornament advantageous has the interesting consequence of making the preference for that trait advantageous. If females choose males with an “attractive” ornament based upon a preference, the likelihood of their offspring inheriting those traits, “attractive” or sexy sons and daughters or choosey females with a strong preference for the “attractive” males, increases dramatically. Over time this dynamic creates a positive feedback mechanism whereby more “attractive” or sexier sons and choosier females are being produced with each successive generation resulting in the runaway selection of both the ornament and the preference. Given time, this type of runaway selection can facilitate the development of a greater preference for and a more pronounced ornament at a rate exponentially, until the costs for producing the ornament outweigh the reproductive benefit of possessing it.[1][2][12][13]

“The two characteristics affected by such a process, namely [ornamental] development in the male, and sexual preference for such development in the female, must thus advance together, and … will advance with ever increasing speed. [I]t is easy to see that the speed of development will be proportional to the development already attained, which will therefore increase with time exponentially, or in a geometric progression.” Fisher, R.A. (1930) The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. ISBN 0-19-850440-3[2]

Fisher makes special note of two possible outcomes when the costs of ornamentation equal or outweigh the reproductive benefit. The first outcome is a counterselection for less ornamented males that will cease the further elaboration of the ornament condition until the advantage attained from sexual preference balances with the costs of ornamentation halting the further exaggeration of both the ornament and the preference to create a condition of relative stability and, (ii) a severing of the entire process if the costs associated with the ornament reduce the number of surviving and reproducing offspring which in turn makes the preference disadvantageous along with the ornamentation.[2]

“Such a process must soon run against some check. Two such are obvious. If carried far enough … counterselection in favour of less ornamented males will be encountered to balance the advantage of sexual preference; … elaboration and … female preference will be brought to a standstill, and a condition of relative stability will be attained. It will be more effective still if the disadvantage to the males of their sexual ornaments so diminishes their numbers surviving, relative to the females, as to cut at the root of the process, by demising the reproductive advantage to be conferred by female preference.” Fisher, R.A. (1930) The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. ISBN 0-19-850440-3[2]

The initiation of Fisherian runaway

[edit]Fisher made a case for how the type of female preference (“attractive’’ through possession alone) necessary for Fisherian runaway could be initiated without any understanding or appreciation for beauty and only a limited facultative sense in his 1915 paper, The evolution of sexual preference.[1] Fisher suggested that points on an organism that draw attention and vary in their appearance amongst the population of males so as to be easily be compared by the females may be enough to initiate Fisherian runaway if somehow the most developed of the points coincides with vigour and vitality but is non-adaptive itself. If a disproportionate amount of females choose the males with the developed point and high vitality based upon the attention drawing of the point, a female preference may be initiated. This hypothesis is compatible with Fisherian runaway in that it establishes an arbitrary attractive based upon a trait that is not necessarily correlated with fitness and the more developed the trait the more non-adaptive it may be, female choice based upon preference alone.[1][4][5][15][16][17]

Alternative hypotheses for the initiation and evolution of male ornamentation

[edit]The assumption that female choice is based upon possession ‘’alone’’ represents one of several hypotheses that utilize this mechanism; two of the most commonly encountered being the sexy sons hypothesis and the good genes hypothesis. The alternative sexy sons hypothesis (also proposed by Fisher) suggests that females choose “attractive” males with the a priori intention of having “attractive” (or sexy sons) where as the good genes hypothesis suggests females choose “attractive” males because the cost of producing “attractive” ornaments is indicative of good genes. Both of these hypotheses use the same mechanism as Fisherian runaway but assume female choice is motivated by an assessment of a potential male mate that is beyond arbitrary attraction. [2][4][5]

Other hypothesis for male ornamentation include:

- Genetic compatibility mechanisms

- Direct phenotypic effects

- Indicator mechanisms (handicap principle and Hamilton-Zuk hypothesis)

See also

[edit]- Sexual selection

- Mate choice

- Secondary sexual characteric

- Sexy sons hypothesis

- Handicap principle

- Good genes hypothesis

- R. A. Fisher

- Modern evolutionary synthesis

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fisher, R.A. (1915) The evolution of sexual preference. Eugenics Review (7) 184:192

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Fisher, R.A. (1930) The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. ISBN 0-19-850440-3

- ^ a b c d Edwards, A.W.F. (2000) Perspectives: Anecdotal, Historial and Critical Commentaries on Genetics. The Genetics Society of America (154) 1419:1426

- ^ a b c d e Andersson, M. (1994) Sexual selection. ISBN 0-691-00057-3

- ^ a b c d e Andersson, M. and Simmons, L.W. (2006) Sexual selection and mate choice. Trends Ecology and Evolution (21) 296:302

- ^ Gayon, J. (2010) Sexual selection: Another Darwinian process. Comptes Rendus Biologies (333) 134:144

- ^ Halliburton, R. (2004) Introduction to Population Genetics. ISBN 0-13-016380-5

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

“gayon10”was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Darwin, C. (1871) The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. ISBN: 978-1-57392-176-3

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pers00was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

“hali04"was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

“ander94”was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

“ander06"was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dobzhansky, T. (1956) Genetics of natural populations XXV. Genetic changes in populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosphila persimilis in some locations in California. Evolution (1) 82:92

- ^ Rodd, F.H., Hughs, K.A., Grether, G.F. and Baril, C.T. (2002) A possible non-sexual origin of mate preference: are male guppies mimicking fruit? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Biology (7) 571:577

- ^ Pomiankowski, A., and Iwasa, Y. (1998) Runaway ornament diversity caused by Fisherian sexual selection. PNAS (95) 5106:5111

- ^ Mead, L.S. and Arnold, S.J. (2004) Quantitative genetic models of sexual selection. Trends in Ecology and Evolution (19) 264:271