User:JoeHK247/sandbox-MainPage

2015 U.S. 1st Edition | |

| Author | Joseph H. Kennedy Jr. |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Cornell Univeristy |

Publication date | 2015 |

| Publication place | United States |

Four Walls (2015) is fictional book within a thesis book by Joseph H. Kennedy Jr. for his Bachelor of Architecture degree at Cornell University completed under the direction of Aleksandr Mergold and Tao Dufour.

The plot centers around the discovery a lost Renaissance book, its destruction and the efforts of various scholars and historians to translate and reconstruct it. The fictional book is a MacGuffin that becomes the subject of a Taiwanese film director’s obsession and the object of controversy between Taiwan and China in which both nations seek to claim ownership over one of its last surviving fragments. As a compromise, the countries agree to collaborate on a documentary of a movie based on a Chinese adaptation of the original Italian book filmed in the Chinese coastal city of Xiamen in the proximity of the Taiwanese controlled island of Kinmen. What results is a series of permanent sets constructed throughout the city that begin to involve the daily lives of its inhabitants and blur the distinctions between movie and reality. The fictional film is a catalyst that allows the city to understand its own history and define its current status. The result is a newly fabricated city identity and a peaceful simulacra that allow the mutual coexistence of the two nations.

Novel Structure

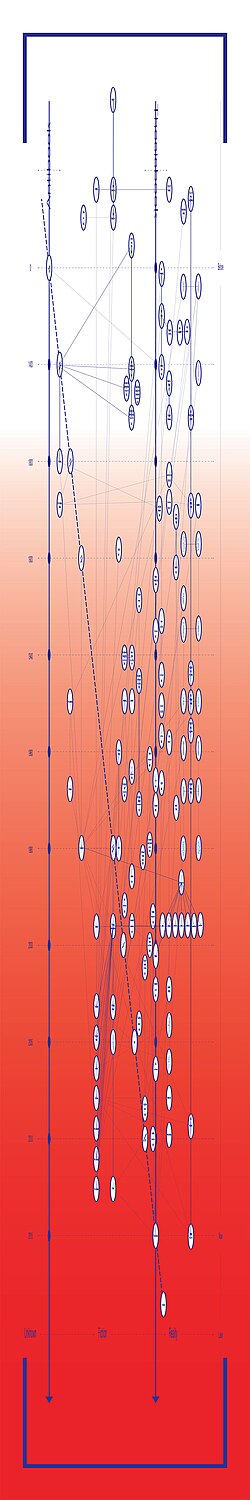

[edit]The structure of the novel can be explained in a diagram. The book is considered to be in the genre of meta-narrative, heavily inspired by hypertext fiction such as Danielewski’s House of Leaves and Grammatron. The narration is intentionally nonlinear with a structure similar to David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, with a self awareness that is likely inspired by Cervantes’ Don Quixote. The quote from Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose, "books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told," refers to a postmodern idea that all texts perpetually refer to other texts, rather than external reality.[1]

The book contains several plots nested within one another that refer to both contemporary and historical events as stories within stories. The story is introduced at a final review in the vacant second floor of Rand Hall, for an architectural thesis in sited in Xiamen China. As the student presents his project, another story emerges about a documentary produced about a Chinese film. From there the narrative becomes a series of false documents that contain and refer to one another. The documentary features the Taiwanese director of the film and his attempt to adapt a fragment of an old book for the screen. While researching the book, the director comes across the story of a mid 18th century Confucian scholar that devotes his family’s fortune to translating a mysterious Italian book signed with the name Alberti. Tracing the ownership of the book before it had come into his possession, the scholar finds it was brought sailors into the Port of Amoy by Dutch sailors. A ship captain, in the harbor of Milan, retrieves a curious book from behind a pile of rubbish and interviews an owner of a bookstore nearby. A grandfather attempts to explain a book he once read to a young girl but find it too difficult and gives up. With her grandfather's frustration so vivid in her memory, the daughter grasps a few strands of his words, finding the story worthwhile to pass on to her children.

-

Old St Peters

-

Maderno St Peters

-

Bramante St Peters

-

Michaelangelo St Peters

-

The Pantheon

-

Vignola Il Gesu

-

Maderno Sant Andrea

-

Borromini San Carlino

-

Palladio Villa Rotunda

-

Bramante Tempietto

Setting

[edit]"A site or its substitute: a set for a project, a stage for a review. Yesterday an architecture studio, tomorrow a library, today an event or its absence - conceived from an obsession with dates and anniversaries. A loosely related collection of near centennials and sesquicentennials that mark the construction of Rand Hall (1911)[2], the birth of the silent film industry in Ithaca (1915)[3], and the founding of Cornell University (1865)[4]. A coincidental alignment of stars signifying an inevitable climax of a story that has yet to materialize, but which still must be written." (With celebrities walking the streets, businessmen investing money in industry, and an international audience through the Wharton Brother's films, Ithaca seemed on the edge of becoming a large metropolitan city. But the movie stars moved, the businessmen left and the skyscrapers never materialized. The city became as it is now, neither small nor large. Infamous and comfortable in its partial anonymity.[5])

-

Library in Rand Hall]]

-

Library in Rand Hall]]

-

Library in Rand Hall]]

-

Library in Rand Hall]]

-

Library in Rand Hall]]

-

Library in Rand Hall]]

Background

[edit]Xiamen

厦门市 | |

|---|---|

| Map | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Fujian |

| Time zone | UTC+8 |

In 1999, China witnessed the country's most extensive and expensive case of government corruption set in the coastal city of Xiamen in the Fujian province. The investigation implicated large scale smuggling operations controlled by the city's most wealthy and prominent business man in a scandal that involved the bribing and manipulation of high level government officials and police in order to evade taxes and import illegal goods. The publicity surrounding the indictment was not only embarrassing for the party in Beijing, but resulted in a government crackdown into the business practices in Xiamen in an effort to fully eliminate any signs of corruption within the government bureaucracy.[6] The newly implemented government regulations on manufacturing and commerce, although not directly targeting foreign interests, threatened the reputation of the city as being an open environment for business and international trade - essentially contradicting city's image when it had been rebranded as one of China's four original Special Economic Zones in the early 1980's with its free market oriented economic policies and flexible governmental for foreign investors. Although most international business continued under the wariness of government scrutiny, prospective foreign investors were intimidated and deterred by recent events, with many quoted stating that the political climate of the city was "bad for business".[7]

The subject of the government investigation and the mastermind behind the smuggling ring was self made businessman and owner of the multibillion dollar company Yuanhua, Lai Changxing. A 2002 edition of Time devotes an entire section to describing his many convictions and his flight to Canada to avoid a sentence of the death penalty. [8]

"All the while, Lai lived spectacularly large. He flitted about China building deluxe villas for his family, blowing money at chic nightclubs, and playing the beneficent philanthropist. A film buff, Lai constructed a $17 million replica of the Forbidden City in the outskirts of Xiamen as a giant set for future movies. He bought the city's soccer team, occasionally moonlighting as goalie. And he broke ground on an 88-story skyscraper that was to be Xiamen's tallest building a worthy flagship for his empire." [9]

The Prequel

[edit]Ten years after the arrest and imprisonment of Lai Changxing's and his conspirators, a Chinese black comedy action flick set in Xiamen was released to widespread mainstream success in China. The film's English title is Crazy Racer, though despite its popularity on the mainland has for the most part not reached audiences overseas or even in other parts of Asia. The film verifies the popular conception of the city's identity being a den of vice and corruption. Shot around famous and easily recognizable landmarks in the city, the film exaggerates the city's recent history of political scandal - referencing the cultural conflicts of Taiwanese cross strait relations and commenting on the latent corruption that had been target within the city's police force and government, with seemingly separate plot trajectories for the individual stories of the characters which are seemingly overshadowed by an unacknowledged/unreferenced yet omnipresent authority that does not necessarily belong to what would be the obvious role (character) of the Chinese government but to the trade and business agendas of foreign capitol that seem to influence the structure and events of the city.

The Taiwanese are not absent within the plot of this fictional drama. Xiamen and its proximity to the Taiwanese controlled Island of Jinmen is locationally in tension between two opposing states and ideologies.[10] The film acknowledges the tension between two nation without directly referring to actual situation. The image of the Taiwanese characters conforms to what must be a mainland Chinese stereotype, one that is undoubtly perpetuated by subtle state-imposed propaganda and a natural xenophobia. The film's Taiwanese characters are introduced as a gang of four ruthless Taiwanese drug-smugglers who in the opening scene are shown killing off a boat full of their co-conspirators in an incident that is triggered by a small miscommunication and mistake on their part. After killing everybody on the boat, the grotesquely overweight leader of the group realizes that there is nobody who remains to pilot the boat to the mainland and that in effect the group is stranded in the water miles away from shore. Their violence, stupidity, opulence and greed are characteristics that are exaggerated and emphasized by the Taiwanese actors in the movie - effectively casting them as fictional cultural ambassadors representative of the majority of Taiwanese. The final climactic action scene occurs in the old military tunnels dug into the mountains of Xiamen[11], whose existence is a memory of the escalating conflict between China and Taiwan. The setting's abandonment and state of disuse acknowledges that the urgency and state of aggression has either completely passed or become largely dormant. In the tunnels, the protagonist engages in an epic fight with the Taiwanese gangster. The movie concludes without either side winning, the police arrive and both characters are arrested. Neither receives either the drugs or the money and the movie ends without any sort of resolution but in a general state of confusion with neither side claiming victory but instead ending up in prison and treated as criminals. Perhaps it is clear from the ending that as an analogy for cross strait relations, the situation is not expected to yield any resolution or victory in the near future, at least from the point of view of the Chinese.

In the scene where the protagonist meets the funeral director/real estate agent (an interesting and symbolically saturated job description in itself) he find himself in a parody of Xiamen's burgeoning property market[12] in which the salesman tries to get him to invest in real estate that is part of a CBD (Central Business District) that is essentially a cemetery plot for his late coach's grave. This dialogue mirrors the existing government zoning practices for new construction in Xiamen which divides undeveloped zones of the island into parcels marketed to large foreign corporations or tower block housing. Later, when the protagonist returns to pay for his coach's elaborate funeral, the salesman asks which denominational currency he wants to use as the spirit money to burn at the wake - which is traditional at Chinese funerals. Tellingly, the protagonist asks for the most valuable form of money, which he later receives as American $100 bills: a sign/symbol of foreign capitol inundating Xiamen. Through another coincidental mix up between the protagonist and the Taiwanese gangsters, the stacks of American dollars given to him to burn turn out to be real - but unknowingly he burns much of it anyways in what is symbolically maybe a larger symbol of defiance. Even though only one westerner appears in a locker room for just a few short seconds in the whole movie, their authoritative economic presence is felt throughout the film while their physical presence may only be marginal.

The police and government are not spared this cynical characterization and are once again cast and molded to fit the corrupt history and contemporary identity of the city. One of the many separate but intertwined dramatic threads of the movie follow the action of two Chinese men that are self-proclaimed professional criminals. The scenes in which they impersonate policemen provide a subtle but critical commentary on the charges of corruption made against the police. When the working class protagonist of the movie, thinking he is a policeman, offers one of them a bribe in exchange for the return of his truck acknowledging that he knows the way in which "business" is conducted in Xiamen, the criminal refuses the bribe and speaks about his moralistic principles of being a cop. Out of his policeman disguise the criminal is extremely greedy, but as a cop he affects having more integrity than the actual police in the city. In effect, the director suggests that the criminal, despite his obvious selfishness and illicit activity is in fact still more honest and has more integrity than the average policeman. This scene, combined with the recurring motif of the frozen Thai smuggler dressed as a policeman makes a rational argument which hints that all police are criminals. When it comes to the actual Xiamen police, the film portrays them as being clueless and inefficient as to the nature of the actual events - they chase the wrong suspects and are ignorant of what's actually going on.

The movie concludes in an implied moralizing statement in relation to the city: The protagonist is portrayed as an honest average working class Chinese man whose integrity is outwardly questioned due to the corruption surrounding him in Xiamen.[according to whom?]

Plot Summary

[edit]Chapter 1

[edit]The new administration has made significant efforts to reestablish the tarnished reputation of the city in order to provide reassurance to the foreign capitol that had been investing in commerce and manufacturing in the region. To restore an environment of security and recreate an ideal image of Xiamen, the newly appointed government in Xiamen reopened and placed funding into the foreclosed production studio and filming backlot that formerly belonged to the infamous Lai Changxing in order to create a feature length film production intended to rebrand the city's tarnished reputation by fostering a local sense of pride and appeal to international investors.

"To recover some of the losses, government officials have tried auctioning Lai's holdings, including the five-star Yuanhua International Hotel and the Forbidden City film studio. But so far, there have been no takers for his major holdings. The Red Chamber reopened briefly as an anticorruption museum last year but was quickly shuttered when tourists seemed to take its opulence as an inspiration instead of a warning. Xiamen residents are bitter that their city has been targeted, when, they say, corruption is equally rampant in other Chinese cities. Indeed, even Beijing admits that smuggling is hardly limited to Xiamen or Fujian" [13]

The subject of the film was an artifact of local legend: A Chinese language film adaptation of an incomplete translation of an Italian book that was believed to have been published in Germany during the mid 15th century.[when?]

Chapter 2

[edit]The project was pitched to government authority in Beijing. Beijing responds with its support and sends a request to the Taiwanese government send the book fragment from the National Palace Museum to Xiamen on a temporary loan in order to research and film the movie. The Taiwanese government is skeptical. It accepts with two conditions. First, that the book is held in under Taiwanese control on the Island of Kinmen to be consulted only under preapproved visits and second, that a Taiwanese director is put in charge of filming the movie.

There is another problem - the planned script for the movie, contains content that is considered violent and politically subversive, something that is not fit for mainland audiences. There is no national rating systems for films shown in China. "As it stands, only films deemed suitable for all ages are released in China, and part of the rigorous censorship process is aimed at supporting this notion, and the Film Bureau makes the necessary cuts." [14] The director refuses to compromise his vision, but the Xiamen government is willing to make a deal. There will be two movies. They will be filmed simultaneously. The first, intended for mainland audiences, will be edited to abide by the censorship requirement of the government authorities. The second is an uncut documentary of the filming of the first movie that is woven into the narrative of the larger city-wide initiative to be distributed outside of the People's Republic of China.

They sign a formal contract, and the Taiwanese director receives his initial funding to begin the research of the book that the film will be based upon. He relocates to the Taiwanese controlled island of Kinmen, just a short half hour ferry ride away from the Chinese city of Xiamen. On weekdays he commutes across the vague border of water separating the two countries, passing through customs control on both sides. He settles into the daily routine, absorbing himself in the task of translating the book as he revisits the lengthy process it required for him to obtain it.

Chapter 3

[edit]The first time he came across evidence of the book's existence was as a student after reading an article about a recent set of acquisitions at the John Soane Museum in London: While replacing the broken glass on the frame of a watercolor by Joseph Gandy, the curators of the museum had discovered a stack of laminated architectural drawings that had been used as a paper backing[15]. After carefully soaking and removing each sheet from the stack, a chemical mist is lightly sprayed over the drawings to bring out their content. Among the pages of old drawings, a series of engravings refer to a set of five anonymous black cloth bound obelisks that were moved to storage when the museum collection had been rearranged several years ago.

On a Saturday, he makes a visit to the museum. The printed description on the wall introduces the work before him.

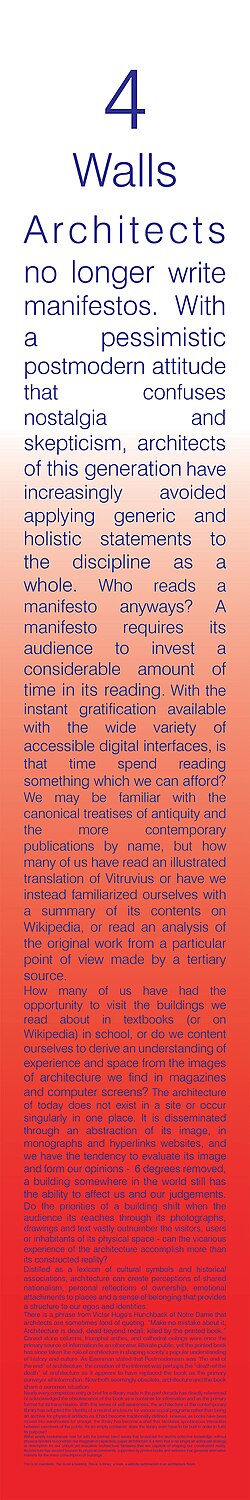

"Embedded in the inciting moment of the Protestant Reformation was the symbolic triumph of the book over architecture. By pinning up his 95 Theses to the door of a Catholic Church (1517), Martin Luther effectively dissolved the authority of the Church and the architecture that reinforced it by means of his book, and later the proliferation of the printed bible.

In the Hunchback of Notre Dame, Victor Hugo proclaimed the death of architecture with the invention of the printing press. “Make no mistake about it, Architecture is dead, dead beyond recall; killed by the printed book.” Carved stone columns, triumphal arches, and cathedral ceilings were once the primary source of information to an otherwise illiterate public, yet the printed book has since taken the role of architecture in shaping society’s popular understanding of history and culture. Architecture, which had until then been responsible for disseminating information to a mass audience, was displaced by the increasing availability of printed information and growing rates of literacy.

While the role of architecture to influence public opinion became increasingly marginalized, Architects turned towards the printed book in order to disseminate their theories and ideas. Soon after the invention of the Gutenberg Press (1450), Leon Battista Alberti released the first printed book of architecture, De Re Aedificatoria (1485), a Renaissance treatise based largely on the ancient Roman work De Architectura by Vitruvius, which followed it one year later in print. The canonical written works by Vignola, Palladio, Ruskin and Semper followed, influencing generations of future architects through their words and not their buildings.

Architecture was further marginalized by the creation of its own image. The invention of the daguerreotype and the creation of the architectural monograph subordinated the physical presence of architecture to the formatting of the book. The book became a didactic tool from which architects and students alike made their impressions of architecture. Paper architecture emerged as the result of these conditions – creating architecture that was drawn, designed, realized, and printed onto the pages of books.

As Eisenman stated that Postmodernism was “the end of the end” of architecture[16], the creation of the Internet was perhaps the “death of the death” of architecture as it appears to have replaced the book as the primary conveyor of information. Now both seemingly obsolete, architecture and the book share a common situation."

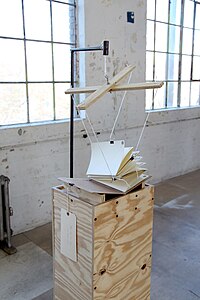

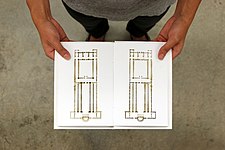

The five obelisks are in fact the covers of five books: canonical Renaissance architectural treaties by Vitruvius, Vignola, Palladio and Alberti stitched together into unbound sheets and folded into portable containers. The books each contain text that describes the fundamental elements that constitute architecture as defined by their authors. The act of turning a page is a gradual effort that produces the physical manifestation of the architecture as described in the book. The act of reading the book creates an expanding sequence of pages that mirrors the ordered reading of the text. A reader’s interaction with successive pages unfolds the book into a large self-structuring spatial enclosure that both describes and embodies certain principles of architecture. A footnote in the museum's research bibliography refers to a lost book - an original by which five copies are based.

-

5 Canonical Orders - Vignola

-

5 Canonical Orders - Vignola

-

5 Canonical Orders - Vignola

-

5 Canonical Orders - Vignola

Chapter 4

[edit]He makes a trip to the library. He is unable to find any copy or record of the original book. He wonders if the existence of the book is a perpetuated myth, dreamt up by bored intellectuals as the incarnation of an ideal book. He comes across conflicting evidence: according to one source, all copies of the book were burned in the Inquisition, claiming the book was heresy that undermined the legitimacy of the Papacy. Another source claims that members of the protestant reformation enacted a nationwide destruction of the book, believing its existence was a threat to creating a closer relationship with God. Whatever the reason for the book's disappearance, there are no copies of the book known to remain today.

Unsatisfied, he searches Wikipedia. A random keyword directs him to an obscure entry in the website’s archive, removed for lack of citations or sources: “The book has no title or common name. It was once a manifesto written in response to the invention of the printing press and what was perceived to be the demise of architecture’s role in conveying cultural information in a predominately illiterate society with the introduction of mass produced and more widely accessible text. The book is its own subject. It is an antibook, a physical argument that information should not be divorced from time and independent of place, that content is not something ubiquitous, ignorant of site and context. It is a device that is specific to its content – not simply a passive container. The book can only be understood through its formatting that creates a reading specific to the interaction between the images and text it contains.” [citation needed] Its former existence is only conjecture. He realizes that without the physical artifact, the information contained is unintelligible and cannot be otherwise reproduced through text or conveyed by speech.

There are, however several primary and secondary sources that attempt to describe the book, with varying degrees of accuracy that at times seem to completely contradict one another. It is known that a single copy of the original book, made it out of Europe before the purge, carried by Dutch ships in the early to the Treaty port of Xiamen (formerly known as Amoy) in possession of the ship's captain. There the book was exchanged, most likely for Chinese tea or porcelain. Due to a lack of Chinese literacy in Italian, the book went unread and unrecognized, traded as a cultural artifact among the bookshelves of fashionable Chinese merchants. It was saved by two hundred years of obscurity, during the First Opium War. After the British captured the island in the Battle of Amoy in 1841, the book came into the possession of a scholar of Confucian literature. Intrigued by the book but unable to decipher its content, the scholar became obsessed with that which was unknown to him, spending a significant portion of his family fortune in order to decipher it.

With the Treaty of Nanking a year later, Xiamen was opened to the west as a treaty port and the scholar found opportunity to seek help from Protestant missionaries. The missionary John Van Nest Talmage mentions the book and his encounter with the scholar in his memoirs, describing his contribution to its translation.[17] The result is a partially transcribed Chinese copy, incomplete due to the sudden death of its author by natural causes. The translation was published posthumously, and the book enjoyed a brief cult popularity.

Chapter 5

[edit]

In 1949 the establishment of Mao's Communist government forced most of the Chinese Kuomintang party to flee from mainland China to the island of Taiwan. A victory by the nationalist army at the Battle of Kinmen prevented the Communists from gaining a strategic foothold to invade Taiwan. The Cultural Revolution of 1966 destroyed nearly all copies of the translated book as well as the last known surviving original text. The last Chinese translation is in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Like many of the cultural artifacts that were evacuated to Taiwan the ownership of the book is the subject of contention.

He turns once more to the web pages of Wikipedia: "The Chinese Civil War resumed following the surrender of the Japanese, ultimately resulting in Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's decision to evacuate the arts to Taiwan. When the fighting worsened in 1948 between the Communist and Nationalist armies, the National Palace Museum and other five institutions made the decision to send some of the most prized items to Taiwan. Hang Li-wu, later director of the museum, supervised the transport of some of the collection in three groups from Nanjing to the harbor in Keelung, Taiwan between December 1948 and February 1949. By the time the items arrived in Taiwan, the Communist army had already seized control of the Palace Museum collection so not all of the collection could be sent to Taiwan. A total of 2,972 crates of artifacts from the Forbidden City moved to Taiwan only accounted for 22% of the crates originally transported south, although the pieces represented some of the very best of the collection."

"During the 1960s and 1970s, the National Palace Museum was used by the Kuomintang to support its claim that the Republic of China was the sole legitimate government of all China, in that it was the sole preserver of traditional Chinese culture amid social change and the Cultural Revolution in mainland China, and tended to emphasize Chinese nationalism. The People's Republic of China (PRC) government has long said that the collection was stolen and that it legitimately belongs in China, but Taiwan has defended its collection as a necessary act to protect the pieces from destruction, especially during the Cultural Revolution. However, relations regarding this treasure have warmed in recent years and the Palace Museum in Beijing has agreed to lend relics to the National Palace Museum for exhibitions since 2009. The Palace Museum curator Zheng Xinmiao has said that the artifacts in both mainland and Taiwan museums are "China's cultural heritage jointly owned by people across the Taiwan Strait."

"The People's Liberation Army extensively shelled the island during the First and Second Taiwan Strait Crises in 1954-1955 and 1958 respectively, which was a major issue in the 1960 United States Presidential Election between Kennedy and Nixon. In the 1950s, the United States threatened to use nuclear weapons against the PRC if it attacked the island."

"Due to fears that the artifacts may be impounded and be claimed by China due to the controversial political status of Taiwan, the museum does not conduct exhibitions in mainland China."

Chapter 6

[edit]

Despite the end of the hostilities, the two sides have never signed any agreement or treaty to officially end the war. During this period, movement of people and goods virtually ceased between PRC- and ROC-controlled territories. Diplomatically during this period, until around 1971, the ROC government continued to be recognized as the legitimate government of China and Taiwan by most NATO governments. The PRC government was recognized by Soviet Bloc countries, members of the non-aligned movement, and some Western nations such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Both governments claimed to be the legitimate government of China, and labeled the other as illegitimate.

In 1987, the ROC government began to allow visits to China. This also proved a catalyst for the thawing of relations between the two sides. After another decade of repressed hostility, the Three Links were re-established to allow regular weekend direct, cross-strait charter flights between China and Taiwan. Flights, postage and direct trade were resumed on July 4, 2008 for the first time since 1950. Despite diplomatic and media efforts by Beijing to portray an easing of military tension with Taiwan, the military build-up against Taiwan continues.[18] Taiwan residents cannot use the Republic of China passport to travel to China, as neither the ROC nor the PRC considers this international travel. The PRC government requires Taiwan residents to hold a Mainland Travel Permit for Taiwan Residents when entering China, whereas the ROC government requires Chinese residents to hold a Mainland Compatriot Pass to enter the Taiwan Area.

Chapter 7

[edit]Although the entire movie is being shot in Xiamen, the book fragment is transported from the National Palace Museum in Taiwan to a secure vault in the military tunnels dug into the island of Kinmen. "Despite boasting one of the world's largest collections of Chinese artifacts and artworks — reputed to number more than 680,000 items — the National Palace Museum seldom sends its treasures overseas for fear that they might be seized by the Chinese authorities, who believe the treasures belong to China." [19]

From this text and from stories that have been passed on in a continuing oral tradition, the director can confirm several facts about the original book: Its covers are bound in a reddish brown paper that measures 9” x 6” with a white strap to keep them closed. Inside are 16 double-sided pages that are each 8.5” by 5.5” in dimension. It is not explicitly mentioned whether the book is bound as a codex, leaflet or in the form of a manuscript. Rather, it is believed that the book is of some nonstandard hybrid form, in which the regular order and adjacency of pages of the archetypical book are subverted in order to create a nonlinear reading of the narrative plot of the book through alternate folding and overlapping of the pages to reveal different patterns of the story, culminating in a single narrative.

The director hires nine master craftsmen well versed in the technique of bookbinding, giving them each the task of recreating the format of the original book. From the few verbal traces and the scant remaining written evidence of the book, the nine craftsmen construct sixty possible variations based on the surviving confirmed facts about the book - one of which must be the form of the original book. The books are made based upon a manual, the I Ching, an ancient divination text and the oldest of the Chinese Classics. The book has heavily influenced the Confucian and Taoist philosophies, and its notation was adopted by the author of the book fragment. The I Ching is used to both retroactively translate the Confucian scholar's work and used as a basis to classify and categorize the sixty variations that were made. When finally convened, the master craftsmen all disagree, arguing for a different book which they each believe must be the original.[according to whom?]

Without any verifiable consensus, the nine craftsmen analyze and diagram their versions of the book, attempting to prove the legitimacy of their decision. The books and the stories they construct begin to subtly influence lives and events both fictional and real in locations across the city.

-

NA 6665 M42

-

NA 6665 M412

-

NA 6665 L202

-

NA 6665 L10

-

NA 6665 M331

-

NA 6665 L201

-

NA 6665 L11

Chapter 8

[edit]A copy of the Confucian scholar's translation of the book is discovered by an architecture student in the Rare and Manuscripts collection of the Kroch Library at Cornell University. Cornell's Kroch East Asian Library holds one of the largest and most significant collections of Chinese research and literature in North America. After seeing the documentary movie by the Taiwanese Director and realizing the book's importance, the architecture student was able to consult numerous sources in Kroch Library's archives on East Asia in order to find track the history of the translated book to the city of Xiamen when it was first translated into Chinese by a Confucian scholar in the mid 19th century and before when it was one of the last surviving book by an Italian architect and author printed in Geneva in the 16th century. [20] Although the book fragment in the possession of the Taiwanese National Palace Museum was assumed to be the last remaining copy of the Italian original, the library archives showed that Charles William Wason, a 1876 Cornell engineering graduate, acquired the book during several extended trips to China between 1909 and his death in 1918 among thousands of other Chinese books, manuscripts, articles and journals that he bound, categorized and eventually bequeathed to Cornell University.[21] Since it was first established, the Wason collection of East Asian literature continued to grow and the book was once again forgotten and lost within the multitude of other information.

Located completely underground, the Carl A. Kroch Library opened in 1992 to provide a new home for the university's renowned Asia Collections and Rare and Manuscript Collections. [22] Contained within the reserved archived section of the Rare and Manuscripts collections of the library, the Chinese book was unavailable for public browsing and could only be directly requested for private viewing if its call number or title was known. However, since its existence was largely unknown, and its physical presence was absent from the shelves of the library, the book could not be accidentally or spontaneously discovered by a library patron either casually browsing shelves or searching for related material. The library’s Rare and Manuscript Collections, including Cornell’s own archives are housed in a secure, climate-controlled vault on the lower level of the Kroch Library. On the same floor is a special reading room where patrons have the opportunity to read, study - and, yet, touch rare books, ancient manuscripts, antiquarian maps, prints, and photographs. As with the other books in the collection, it could only be accessed for short periods of time and patrons were prohibited from scanning or photographing the work. So by complete chance, the book was found and identified by the architecture student. During brief sessions in the reading room with the book, the architecture student adopted the book as the subject of his undergraduate thesis. His project attempts to translate and spatialize the Chinese book into an architectural proposal for a reading room that is devoted to the original book it describes as part of the new Fine Arts Library being designed and constructed in Rand Hall on the Cornell campus.

Chapter 9

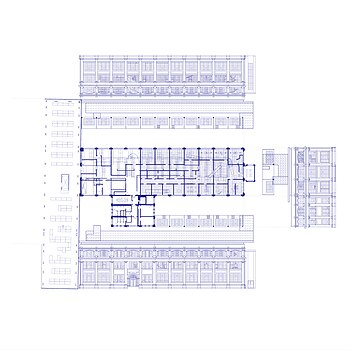

[edit]The construction of Rand Hall in 1911 coincided with the Xinhai Revolution that marked the end of the Qing Dynasty's imperial rule over china with the abdication of the last emperor and the establishment of China's first republic. While both the island of Taiwan and mainland China have claimed to be the legitimate inheritors of the revolutionary legacy that followed the fall of the Qing Dynasty as a means of validating their political rights, Rand Hall serves as a detached site from which to consider their shared histories using Cornell University's extensive collection of written material relating to that period in the nation's history. On May 9th, 2015 the disused portion of the building's second floor, soon to become the college's new Fine arts library, is appropriated as the space for an architecture thesis project that considers the conflicting histories of Taiwan and China within the narrative of the indecipherable book discovered in the university's East Asian rare manuscripts collection.

-

Rand Hall History - Site

-

Rand Hall History - Axon

-

Rand Hall History - Plan and Elevations

The Characters

[edit]Stephanie

[edit]She is a biologist teaching at Xiamen University who studies the Conchology of mollusks.

Justin

[edit]He is the son of a farmer that has moved from the land to the sea.

Daniel

[edit]He is a successful actor and choreographer living in Tong'an.

Yoon

[edit]She is an artist and entrepreneur from Dafen who recently moved to the Wushipu Oil Painting Village.

Elie

[edit]He is an assembly line worker in the Fujian Longhai paper mill and a descendant of the Confucian scholar.

Anders

[edit]He is a Land Surveyor hired to chart the mountains and tunnels on the island of Xiamen.

Brad

[edit]He is a former coal miner working in the harbor of Xiamen.

Tim

[edit]He is a Taiwanese architect designing a bathhouse on a small island off of Kinmen.

The Library

[edit]-

Rand Hall Exploded Axon

-

Interpretive Diagram of Relationships

-

Manifesto Text

-

Map Data Conversion

Program

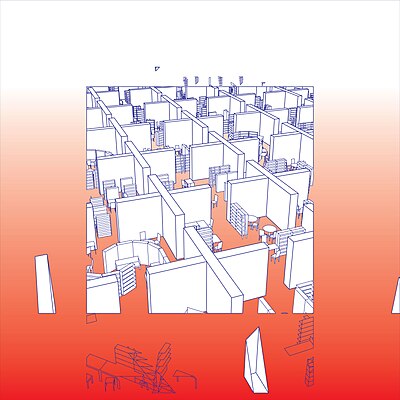

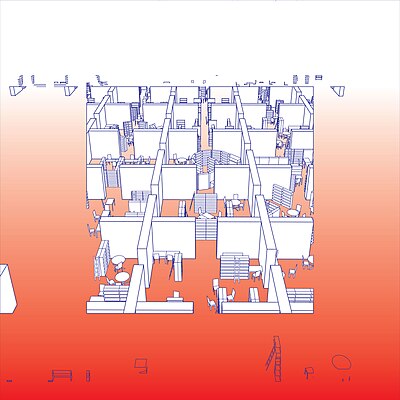

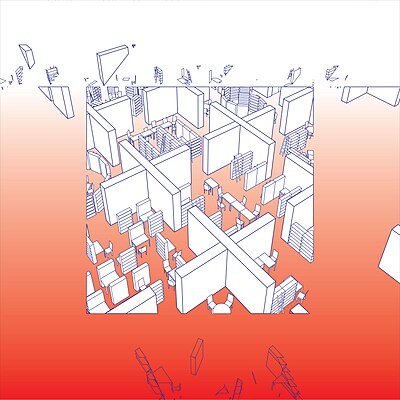

[edit]The library is designed as a physical repository for all of the information contained within Wikipedia. It contains an endlessly repeating set of reading rooms that form a cogent labyrinth of bookshelves, ladders and furniture and the occasional spiral stair. The circulation between the spaces intentionally replicates the use of the hyperlink as a navigational tool between related content in a digital text or online article. The rooms themselves can be rearranged within the framework of the walls and doors of the library, creating an infinitely variable set of possible connections between spaces. The floors of the library have an ambiguous relationship to one another. The ceiling heights vary and are subject to change - a spiral staircase links the floors regardless of the gaps in between. While also being stacked on top of one another, the series of floors extend on all sides to connect to one another without breaking their horizontal level - essentially operating as a 3-manifold within a four dimensional space. So, in effect the separate floors connect to one another as if they were all mapped onto the two dimensional surface of a sphere that would link back to itself at its edges.

Design

[edit]Each reading rooms is devoted to housing the books of a specific and uniquely bound physical format. The 60 versions of the book produced by the master craftsmen hired by the director are the generators of 81 separate rooms within the library. The composition of the books, the order in which the pages are viewed, and their adjacency to one another are all attributes that are abstracted and spatially manifested into the layout of the furniture and bookshelves that both divide and suggest alternate means of inhabiting each of the reading rooms. Their arrangement and adjacency is based upon the relationship between the categories of the different types of books, classified into a spatial progression between places)

Classification System

[edit]The classification system is a modification of the Library of Congress Classification System combined with the Universal Decimal Classification System and the Dewey Decimal System on which they are both based. Her method is heavily influenced by the work of information scientist Paul Otlet and his unrealized plans for a Mundaneum to be a physical repository to house all of the world's knowledge that went through designs by Le Corbusier that were intended to be built in Geneva, Switzerland. The books are classified beginning with the general class for the architecture library prefix NA 6665 followed by a modified call number that refers to the construction of the books. Since the books are blank, empty, and devoid of any content, the classification systems that were designed to refer to the subject matter of the information contained within books do not directly apply to categorizing the books themselves. Thus the notation is re appropriated in order to refer to the format and construction of the books and are divided into several classes:

B refers to the format of the Book as we are most familiar with it today. A series of folded leaflets bound into a folio.

M refers to the format of the Map which is essentially a single large sheet that has been folded without being cut.

L refers to the format of the Leporello that is a series of interconnected pages that unfold in sequence. Its construction is somewhere in between that of a generic Book and a Map.

C refers to the format of the Fan that rotates off of a single point.

I refers to the format of the Index Card that is a collection of loose sheets of paper contained within a closed cover.

O refers to the format of the Other books that are hybrids of the Book, Map and Leporello types.

(Her house is a shell, a reflection of her grandfather's piano, on islands separated by a short gap of water but linked by an aerial tram)

Format

[edit]The possible formats for the original book are reproduced in a set of 60 unique variations that abide by the rules described in the oral and written texts of surviving sources. Each book contains sixteen double sided pages sized 8.5” x 5.5”. The books are categorized according to the Library of Congress classification system and their structure is carefully documented and divided into an informal genealogy.[clarification needed] A bookcase contains and organizes the books. A library contains and organizes the bookcases.

It addresses two formats of information interface from opposite sides. One considers the rarefied book as a physical artifact that can create a interrelationship and experience of text, image and narrative through its inherent formatting absent of either subject matter or content. The other is the Internet, which has largely replaced the object of the book as the primary conveyance of information, which still contains an inherent structure lacking physical constraints to allow for a more fluid non linear reading of the information.

-

Reading Rooms

-

Reading Rooms

-

Reading Rooms

-

Reading Rooms

-

Reading Rooms

-

Reading Rooms

Initial Reception

[edit]The premise of the book is questioned - whether it is an architectural problem or a general commentary on contemporary society's relationship with media technologies and the role of the physical object within digitized space. Jonathan Ochshorn, a professor of building technology in the architecture program at Cornell, writes his criticism of the premise of building a new library in Rand Hall from both a structural and conceptual standpoint.[23] Is the need for a library present with the declining use of the book?

Cinematic Influences

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

The book's main character of the Taiwanese director is partially derived from the 2001 Chinese American film collaboration, Big Shot's Funeral by Chinese director Xiaogang Feng, that follows the fictional reproduction of Bernardo Bertolucci's acclaimed The Last Emperor. The American director of the new film, played by Donald Sutherland, struggles with the problem of creating a more authentic Chinese cultural remake of the original film, being himself a foreigner.[24] The high expectations and stress of the project cause him to fall into a coma, leaving a Chinese cameraman hired by the director's Chinese-American assistant to produce documentary comedy of the director's anticipated funeral. [25] The actual film, which is distributed in both China and the United States, is a satirical commentary on cross cultural exchange as well as emerging capitalism in China.[26]

The book also takes inspiration from another of Bertolucci's films, The Spider's Stratagem, which is an Italian adaptation of Borges's short story, Theme of the Hero and the Traitor.

Spike Jonze's film Adaptation.

Interpretations

[edit]This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2015) |

It is believed that the main protagonist, the film director, is the mandarin alias of the author who is of Taiwanese/American descent. Critics speculate as to whether the author was writing with bias when speculating on Cross-Strait relations.

The move of the Wharton Brother’s studio from Ithaca to Santa Cruz mirrors the author’s move from Santa Cruz to Ithaca.

The book is considered to be part of a literary legacy deriving from Vladimir Nabokov (Pale Fire) and Thomas Pynchon (author of V. and the Crying of Lot 49), both of which spent significant time at Cornell University. Like the protagonists of Pynchon’s novels, the characters chase after elusive codes and symbols in a hopeless search for meaning.

External Links

[edit]Reference

[edit]- ^ Christopher Butler. Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-280239-2 — see pages 32 and 126 for discussion of the novel.

- ^ "2017-RAND HALL – Facility Information". Cornell University. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ http://www.whartonstudiomuseum.org/

- ^ https://150.cornell.edu/about

- ^ http://www.ithacamademovies.com/history/

- ^ Menshausen, Simone. "Corruption, Smuggling and Guanxi in Xiamen, China" Internet Center for Corruption Research

- ^ Beech, Hannah (2014-07-28). "Smuggler's Blues". Retrieved 2015-03-18.

- ^ "Smuggling Kingpin Lai Changxing" Global Times

- ^ Beech, Hannah (2014-07-28). "Smuggler's Blues". Retrieved 2015-03-18.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/17/world/asia/kinmen-seeks-to-evolve-as-china-and-taiwan-improve-ties.html?_r=0

- ^ http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/tourists-take-pictures-in-a-tunnel-which-was-for-military-news-photo/458852710

- ^ http://issuu.com/gsdharvard/docs/common_frameworks_part1

- ^ Beech, Hannah (2014-07-28). "Smuggler's Blues". Retrieved 2015-03-18.

- ^ Coonan, Clifford "Chinese Cinemagoers Keen on Film Ratings System" The Hollywood Reporter, 8/26/2013

- ^ http://www.soane.org/news/article/gandy-un-framed-the-secret-life-of-a-watercolour

- ^ Corbo, Stefano. "From Formalism to Weak Form: The Architecture and Philosophy of Peter Eisenman" Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., Jan 28, 2015

- ^ http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17002/17002-h/17002-h.htm

- ^ Fisher, Richard (2010). China's Military Modernization: Building for Regional and Global Reach. Stanford Security Studies. ISBN 0-8047-7195-2

- ^ "New Japan law opens way for exhibits" China Post

- ^ http://asia.library.cornell.edu/ac/AsiaCollections/About_Kroch_Library

- ^ http://asia.library.cornell.edu/ac/Wason/History_3

- ^ http://asia.library.cornell.edu/ac/AsiaCollections/About_Kroch_Library

- ^ http://jon.ochshorn.org/2015/04/cornells-proposed-fine-arts-library-in-rand-hall/

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/movies/movie/266377/Big-Shot-s-Funeral/overview

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0287934/plotsummary?ref_=tt_ov_pl

- ^ http://www.popmatters.com/review/big-shots-funeral/

Further Reading

[edit]Carpo, Mario. "Architecture in the Age of Printing" Cambridge: MIT Press 2001.

Crumey, Andrew. "Pfitz" New York: Picador, 1997.

Hulshof, Michiel and Roggeveen, Daan. "How the City Moved to Mr. Sun : China's New Megacities" Amsterdam: SUN, 2011.

Category:Literature about literature Category:Taiwan Strait Category:Politics of China Category:Politics of Taiwan Category:Library cataloging and classification

![Library in Rand Hall]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_2.JPG/225px-Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_2.JPG)

![Library in Rand Hall]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2e/Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_12.JPG/225px-Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_12.JPG)

![Library in Rand Hall]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_1.JPG/225px-Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_1.JPG)

![Library in Rand Hall]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_9.JPG/225px-Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_9.JPG)

![Library in Rand Hall]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_4.JPG/225px-Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_4.JPG)

![Library in Rand Hall]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_3.JPG/225px-Thesis_Review_-_Final_Image_3.JPG)