User:Dr. Grampinator/sandbox/Crusader States Chronology

This chronology presents the timeline of the Crusades from the beginning of the First Crusade in 1095 to the fall of Jerusalem in 1187. This is keyed towards the major events of the Crusades to the Holy Land, but also includes those of the Reconquista and Northern Crusades as well as the Byzantine-Seljuk wars.[1]

The First Crusade

[edit]In order to recover the Holy Land and aid the Byzantines in their fight against the Seljuks, the First Crusade was called for by Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1095 and culminated with the capture of Jerusalem in 1099.[2]

1095

- 1–7 March. The Council of Piacenza is convened, with ambassadors from Alexius I Komnenos beseeching Urban II for help in fighting the Seljuk Turks.[3][4][5]

- 17–27 November. At the Council of Clermont, Urban II issues a call to arms to reconquer the Holy Land for Christendom.[6]

1096

- Early February. The First Crusade begins as the leaders are identified and form their armies.[a][8]

- 12 April. The People's Crusade commences with Peter the Hermit and his army arriving at Cologne.[b][9]

- August 15. The Armies of the First Crusade begin to depart for the Holy Land.[10]

- 21 October. The People's Crusade ends with their defeat at the Battle of Civetot.[11]

- November. Hugh of Vermandois and his army arrive at Constantinople.[12]

- 23 December. The army led by Godfrey of Bouillon and his brother Baldwin of Boulogne arrive at Constantinople.[13]

1097

- 26 April. The army of Bohemond of Taranto led by his nephew Tancred arrives at Constantinople. Bohemond himself had arrived earlier on 2 April.[14]

- 27 April. The Provençal army of Robert of Flanders arrives at Constantinople.[15]

- Late April. Raymond of Saint-Gilles and Adhemar of Le Puy arrive with their armies at Constantinople.[16]

- 14–28 May. The armies of Stephen of Blois and Robert Curthose arrive in Constantinople.[17]

- 14 May – 19 June. The Seljuk Turks under Kilij Arslan surrender the city of Nicaea to the Byzantines after the Crusader Siege of Nicaea.[18]

- 1 July. After defeating the Seljuk forces of Kilij Arslan at the Battle of Dorylaeum, the Crusaders capture Arslan's treasure.[19]

- 20 October. The Siege of Antioch begins, pitting the combined Crusader armies against the defenders of Antioch.[20]

1098

- 9 March. Baldwin of Boulogne establishes the County of Edessa, the first of the Crusader states.[c][21]

- 3 June. The city of Antioch is captured. The next day, a counterattack is mounted by Kerbogha.[22]

- 28 June. The forces of Kerbogha are defeated at the Battle of Antioch.[23]

- Early July. The Principality of Antioch is established under Bohemond I.[d][24]

- 1 August. Adhemar of Le Puy, the pope's representative for the expedition, dies of the plague.[25]

1099

- 7 June – 15 July. The Crusaders capture the Holy City after the Siege of Jerusalem.[26]

- 22 July. Godfrey of Bouillon becomes the first ruler of Jerusalem.[e][28]

- 29 July. Urban II dies, never knowing that his crusade was successful.[5]

- 1 August. Arnulf of Chocques is elected as the first Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem.[29]

- 12 August. The First Crusade ends with the successful Battle of Ascalon, defeating the Fatimids under Al-Afdal Shahanshah.[f][31]

- 13 August. Paschal II is elected pope.[32]

- 25 December. Arnulf of Chocques abdicates and Daimbert of Pisa becomes Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem.[33]

- (Date unknown). Tancred becomes prince of Galilee.[34]

The Kingdom of Jerusalem

[edit]The Kingdom of Jerusalem was formed in 1099 and enjoyed relative success against the warring Seljuks and Fatimids in its early years until the advent of the Zengids in 1127.[35]

1100

- 18 July. Godfrey of Bouillon dies.[28]

- August. A force led by Bohemond of Taranto is defeated by that of Gazi Gümüshtigin at the Battle of Melitene. Bohemond is captured, to be held for three years. Tancred then becomes regent of Antioch.[36]

- 2 October. Baldwin of Bourcq becomes Count of Edessa.[37]

- Christmas Day. Baldwin I of Jerusalem is elected king.[g][38]

1101

- Summer. The Crusade of 1101 begins with a force of Lombards, Nivernais, French and Bavarians to reinforce the young Kingdom of Jerusalem.[39]

- August. The Seljuks and Danishmendids defeat the Lombard force at the Battle of Mersivan.[h][40]

- August. The remaining Crusader forces are defeated by Kilij Arslan at Heraclea Cybistra, ending the Crusade of 1101.[i][41]

- 7 September. Baldwin I of Jerusalem leads his crusader force to victory over the Fatimids at the First Battle of Ramla.[42]

1102

- Spring. The first Siege of Acre by the Crusaders is inconclusive.[43]

- 17 May. The Fatimids defeat the forces of the Kingdom of Jerusalem at the Second Battle of Ramla.[42]

- 28 May. The Crusaders recover from their loss at Ramla and defeat the Fatimids at the Siege of Jaffa.[44]

- (Date unknown). Mons Peregrinus (Castle of Mount Pilgrim) is constructed by Raymond of Saint Gilles near Tripoli.[45]

- (Date unknown). The Crusader states begin their Siege of Tripoli, then under the Seljuks. The siege would last until 12 July 1109, with a Crusader victory.[46]

1103

- August. Bohemond of Taranto returns to Antioch after being ransomed by Latin Patriarch Bernard of Valence with the help of the Armenian noble Kogh Vasil.[47]

1104

- 7 May. The Crusader states of Antioch and Edessa, are defeated by Jikirmish and Sökman at the Battle of Harran, their first major battle.[48]

- Afterwards. Baldwin of Bourcq (then count of Edessa and later king of Jerusalem as Baldwin II) and Joscelin I of Edessa are taken captive.[49] Tancred of Galilee becomes regent of the County of Edessa. Richard of Salerno becomes governor.

- 25 May. With the help of a Geneose fleet, Baldwin I of Jerusalem defeats the Fatimids at the second Siege of Acre that began 20 days earlier.[50]

1105

- Spring. Tancred is successful at the Battle of Artah, defeating the Aleppine forces of Ridwan.[51]

- 27 August. Baldwin I of Jerusalem defeats the Fatimids at the Third Battle of Ramla.[52]

1106

- Late. Jikirmish is murdered by Jawali Saqawa as he takes Mosul. Baldwin of Bourcq is now Jawali's prisoner.[53]

1107

- Autumn. The Norwegian Crusade led by Sigurd the Crusader begins.[54]

1108

- Summer. Baldwin of Bourcq is released and returns to Edessa.[55]

- September. Negotiations between Alexius I Komnenos and Bohemond of Taranto begin, resulting in the Treaty of Devol in which Bohemond agrees to become a vassal to the emperor. This ended the Siege of Dyrrhachium.[56]

1109

- 12 July. The Crusaders take the city after the successful conclusion of the Siege of Tripoli. This led to the establishment of the County of Tripoli under Bertrand of Toulouse.[j][46]

1110

- February – 13 May. Baldwin I of Jerusalem and Bertrand of Toulouse defeat the Fatimids at the Siege of Beirut.[57]

- 19 October – 5 December. Baldwin I and Sigurd the Crusader capture the city from the Fatimids after the Siege of Sidon.[58]

- (Date unknown). Tancred takes control of the Arab fortress of Krak des Chevaliers.[59]

1111

- 5 March. Bohemond II of Antioch becomes prince of Antioch upon the death of his father Bohemond I. Bohemond II was under the regency of Roger of Salerno until 1119.[60]

- 13–29 September. The forces of Baldwin I of Jerusalem meet those of Mawdud at the Battle of Shaizar. The battle is inconclusive and the Crusaders withdraw.[61]

1112

- April–June. Mawdud attacks Edessa.[61]

- 12 October. Vasil Dgha becomes ruler of Raban and Kaisun upon the death of his father Kogh Vasil.[62]

- 12 December. Tancred dies and is succeeded by Joscelin I of Edessa at Galilee.[34]

- December. Arnoulf of Chocques is elected as Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem.[63]

1113

- 15 February. Paschal II issues papal bull Pie postulatio voluntatis recognizing the Knights Hospitaller.[64]

- 28 June. Mawdud and Toghtekin lead the Seljuks to victory over the forces of Baldwin I of Jerusalem at the Battle of al-Sannabra.[65]

- August. Having repudiated his wife Arda of Armenia, Baldwin I of Jerusalem marries Adelaide del Vasto.[66]

1114

1115

- Summer/Fall. Baldwin I of Jerusalem begins construction of the castle Krak de Montreal.[67]

- 14 September. A Crusader army led by Roger of Salerno defeats the Seljuks under Bursuk ibn Bursuk at the Battle of Tell Danith (Battle of Sarmin).[68]

1116

- (Date unknown). The Armenian lands of Vasil Dgha are conquered by Baldwin I of Jerusalem.[69]

1117

1118

- March. Baldwin I of Jerusalem launches a campaign against Egypt where he becomes ill and dies at el-'Arish.[38]

- 2 April. Baldwin II of Jerusalem becomes king.[37] Joscelin I of Edessa becomes Count of Edessa.

- December. Roger of Antioch and Leo I of Armenia capture Azaz from Ilghazi.[70]

1119

- 1 February. Callixtus II becomes pope.[71]

- 28 June. Roger of Salerno's Crusader army is annihilated by the forces of Ilghazi at the Battle of Ager Sanguinis (Battle of the Field of Blood). Baldwin II of Jerusalem assumes the regency of Antioch.[72]

- 14 August. Baldwin II of Jerusalem defeats Ilghazi at the Battle of Hab (also known as the Second Battle of Tell Danith).[73]

- (Date unknown). Hugues de Payens founds the Knights Templar and becomes its first Grand Master.[74]

1120

- 16 January. The Council of Nablus establishes the written laws of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[75]

1121

1122

- 8 August. The Venetian Crusade begins with Battle of Jaffa in which the Venetian fleet defeated the Fatimids.[76]

- 13 September. Joscelin I of Edessa and Waleran of Le Puiset are captured by Belek Ghazi, later emir of Aleppo.[77]

1123

- 18 March. The First Council of the Lateran is convened.[k][79]

- 18 April. Baldwin II of Jerusalem is captured by Belek Ghazi at Kharput, joining Joscelin I and Waleran.[80]

- 29 May. A Crusader force under Eustace Grenier defeats the Fatimids at the Battle of Iberlin.[81]

1124

- 29 June. The Venetians and Franks are successful in the Siege of Tyre, capturing the city from Toghtekin and ending the Venetian Crusade.[76]

- 29 August. Baldwin II of Jerusalem is released after paying Timurtash a ransom and providing additional hostages, including his daughter Ioveta of Bethany.[82]

- 6 October. Baldwin II of Jerusalem begins Siege of Aleppo to secure the release of Timurtash's hostages.[83]

1125*

- 25 January. Ibn al-Khashshab is reinforced by al-Bursuqi, causing Baldwin II of Jerusalem to withdraw from the Siege of Aleppo.[83]

- 11 June. Baldwin II of Jerusalem and Leo I of Armenia defeat the forces of al-Bursuqi and Toghtekin at the Battle of Azaz.[84]

- September. Ioveta of Bethany and the other hostages are ransomed with the booty of Azaz.[84]

1126

- 26 January. Baldwin II of Jerusalem defeats Toghtekin at the Battle of Marj al-Saffar but fails to take Damascus, the untimate objective of the campaign.[85]

Zengi and the Fall of Edessa

[edit]In 1094, the governor of Aleppo, Aq Sunqur al-Hajib, was beheaded by Tutush I for treason. His son Imad al-Din Zengi was raised by Kerbogha, the governor of Mosul, and would rise to challenge the Crusader states. His successful Siege of Edessa would both result in the Second Crusade and the eventual fall of the County of Edessa.[86]

1127

- September. Zengi becomes atabeg of Mosul, beginning the Zengid dynasty.[86]

1128

- 12 February. Toghtekin dies and is succeeded by his son Taj al-Muluk Buri.[87]

- 18 June. Zengi becomes atabeg of Aleppo.[88]

1129

- 2 June. Fulk V of Anjou, later king of Jerusalem, marries Melisende of Jerusalem, the heir to the kingdom.[89]

- October – 5 December. Baldwin II of Jerusalem begins the Crusade of 1129 against Damascus defended by Buri. The attack was abandoned with only the castle of Banias captured.[90]

1130

- 14 February. Innocent II becomes pope.[91]

- February. Bohemond II of Antioch is killed in battle with the Danishmends near the Ceyhan River. He is succeeded at Antioch by his daughter Constance of Antioch under the guardianship of Joscelin I of Edessa and regency of Baldwin II of Jerusalem.[92]

- Later. Alice of Antioch (wife of Bohemond II and daughter of Baldwin II) attempts to make an alliance with Zengi and is expelled from Antioch.[92]

- Spring. Zengi lays siege to the Crusader-held city of al-Atharib defended by Baldwin II of Jerusalem. After winning the Battle of al-Atharib, Zengi reduces the city to rubble.[93]

1131

- 21 August. Baldwin II of Jerusalem dies and is succeeded by his daughter Melisende of Jerusalem and her husband Fulk of Jerusalem as queen and king of Jerusalem. Fulk assumes the regency of Constance of Antioch.[94][95]

- (Date unknown). Joscelin II of Edessa becomes Count of Edessa after his father Joscelin I of Edessa was gravely wounded in battle with the Danishmends.

1132

- 11 December. Shams al-Mulk Isma'il captures Banias from the Crusaders.[96]

- (Date unknown). Alice of Antioch reasserts her claim to Antioch.[97]

1133

- (Date unknown). Zengi raids the County of Tripoli and defeats the Crusades at the Battle of Rafaniyya.[98]

1134

- Late. Hugh II du Puiset revolts against Fulk of Jerusalem and is exiled for three years.[99]

1135

- 17 April. Zengi's campaign against Antioch begins with the capture of al-Atharib, followed by Zardana, Ma’arat al-Nu’man, Ma’arrat Misrin and Kafartab.[100]

- 1 December. Henry I of England dies.[101]

- Later. Raymond of Poitiers departs England. Upon hearing that he planned to marry Constance of Antioch, Roger II of Sicily orders him arrested.

- (Date unknown). Bernard of Valence dies and Ralph of Domfront becomes the second Latin Patriarch of Antioch.[102]

- (Date unknown). Pons of Tripoli is repelled by Zengi in the Battle of Qinnasrin.[103]

1136

- 19 April. Raymond of Poitiers arrives at Antioch. Patriarch Ralph of Domfront convinces Alice of Antioch that Raymond is there to marry her, and she allows him entry into the city.

- After April. Constance of Antioch marries Raymond of Poitiers with the help of the patriarch.

1137

- (Date unknown). Forces under Fulk of Jerusalem are defeated by those of Zengi at the Battle of Ba'rin.[104]

- (Date unknown). Fulk of Jerusalem takes refuge in the castle at Montferrand and surrenders to Zengi.[105]

1138

- 14–20 April. John II Komnenos leads a Byzantine and Frankish force in the unsuccessful Siege of Aleppo, with the city defended by Zengi.[106]

- 28 April – 21 May. The Byzantine and Frankish forces are successful in their Siege of Shaizar. The siege captured the city but not the citadel, and the emir became a vassal of Byzantium.[107]

1139

- 29 March. Innocent II issues papal bull Omne Datum Optimum giving papal protection to the Knights Templar.[108]

1140

- 12 June. Mu'in al-Din Unur enters a pact with Fulk of Jerusalem and they take Banias.[109]

- 2 June. Zengi unsuccessfully besieges Damascus and retires from Syria.[109]

1141

1142

- (Date unknown). Raymond II of Tripoli grants the Krak des Chevaliers to the Knights Hospitaller.[110]

1143

- 25 December. Fulk of Jerusalem is killed in a hunting accident and Baldwin III of Jerusalem becomes king of Jerusalem, co-ruling with his mother Melisende of Jerusalem.[111]

1144

- 28 November – 24 December. Zengi is successful in his Siege of Edessa that would both result in the Second Crusade and the eventual fall of the County of Edessa.[112]

- (Date unknown). Pope Celestine II issues the bull Milites Templi (Soldiers of the Temple) protecting the Knights Templar.[113]

1145

- January. Zengi's successful attack on the fortress at Saruj results in the Fall of Saruj.[114]

- 15 February. Eugene III becomes pope.[115]

- (Date unknown). Eugene III issues the bull Militia Dei (Knights of God) providing for the Knights Templar's independence from local clerical hierarchies.[116]

The Second Crusade

[edit]The fall of Edessa in 1144 would lead to the Second Crusade which would include French and German expeditions to the Holy Land, a campaign in Iberia (part of the Reconquista) and the Wendish Crusade (part of the Northern Crusades). The failure of the campaigns in the Holy Land would reverberate for decades.[117]

1145

- 1 December. Eugene III issues the papal bull Quantum praedecessores calling for the Second Crusade.[118]

1146

- 1 March. The reissue of papal bull Quantum praedecessores allows Bernard of Clairvaux to preach the crusade throughout Europe.[119]

- 31 March. Louis VII of France and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine take the cross and lead the French forces of the crusade.[120]

- 5 October. Eugene III issues the first part of the papal bull Divina dispensatione urging Italians to join the Second Crusade.[121]

- October–November. Joscelyn II of Edessa recaptures Edessa but loses it shortly after Nūr-ad-Din's successful second Siege of Edessa.[122]

- 24 December. Conrad III of Germany and Frederick Barbarossa take the cross and lead the German forces of the crusade.[123][124]

1147

- 16 February. French forces meet in Étampes to discuss their route to the Holy Land.[125]

- Spring. In the first battle of the crusade, Baldwin III of Jerusalem is defeated by Damascene forces under Mu'in ad-Din Unur at the Battle of Bosra.[126]

- June. The French contingent leaves for Constantinople.[125]

- August. The Provençal contingent under Alfonso Jordan departs for Constantinople burt engage in no combat.[127]

- September 10. The German contingent arrives in Constantinople and engage with the Byzantines at a Skirmish in Constantinople. They depart without waiting for the French.[128]

- 25 October. The German forces of Conrad III of Germany are defeated by the Seljuks led by sultan Mesud I at the Battle of Dorylaeum.[129]

- November. The remnants of the Germany army meets up with the French contingent at Nicaea. A wounded Conrad III of Germany departs for Acre.[130]

- 24 December. The combined crusader army successfully engages the Seljuks at the Battle of Ephesus.[131]

- Later. Louis VII of France fends off the Seljuks at the Battle of the Meander.[132]

- Approximate. De expugnatione Lyxbonensi, an account of the second Siege of Lisbon, is written.[133]

1148

- 6 January. A French crusader army led by Louis VII of France was defeated by the Seljuks at the Battle of Mount Cadmus.[134]

- 24 June. The Haute Cour of Jerusalem meets with the Crusade leaders to determine the strategy at the Council of Acre. It was decided that the objective would be Damascus.[135]

- 1 July – 30 December. Ramon Berenguer IV leads a multi-national force in the successful Siege of Tortosa as part of the Second Crusade.[136]

- 24–28 July. The Crusader forces are defeated at the Siege of Damascus by Mu'in ad-Din Unur as supported by Nūr-ad-Din and Sayf al-Din Ghazi I.[137]

- 28 July. The Crusader commanders retreat to Jerusalem, ending the Second Crusade.[138]

The Reign of Nūr-ad-Din

[edit]The death of Zengi in 1146 would give rise to an even more powered leader of the Zengid dynasty, his son Nūr-ad-Din who would come to dominate Syria and, to some extent, Egypt.[139]

1149

- 29 June. The army of Nūr-ad-Din defeats the crusaders under Raymond of Poitiers at the Battle of Inab, establishing him at the leader of the counter-Frankish forces. Raymond is killed during the battle.[140][141]

1150

- August. A Crusader force commanded by Baldwin III of Jerusalem repels an attack by Nūr-ad-Din at the Battle of Aintab. Baldwin III then evacuates the County of Edessa.[142]

1151

- Spring. After Joscelin II of Edessa ceded Turbessel to the Byzantines, a coalition of Nūr-ad-Din, Mesud I and Kara Arslan leads to Fall of Turbessel.[143]

- Late. Raymond II of Tripoli is killed by Assassins, the first such Christian leader murdered by the sect.[144]

1152

- Early. Baldwin III of Jerusalem demands coronation as sole ruler of the kingdom and the Haute Cour of Jerusalem divides the kingdom into two administrative districts.[111]

1153

- 25 January – 22 August. Baldwin III of Jerusalem leads the assault on the Fatimid fortress in the successful Siege of Ascalon.[145]

- Early. Constance of Antioch marries Raynald of Châtillon who then becomes prince of Antioch ruling jointly with Constance.

1154

1156

1157

- 19 June. A Crusader army led by Baldwin III of Jerusalem was ambushed and badly defeated by Nūr-ad-Din at the Battle of Lake Huleh.[146]

1158

- 15 July. Crusader forces of Baldwin III of Jerusalem repel an attack by Nūr-ad-Din at the Battle of Butaiha (Putaha).[147]

1159

- 12 April. Manuel I Komnenos enters Antioch, establishing himself as the suzerain of the principality.[148]

- 7 September. Alexander III becomes pope.[149]

- (Date unknown). Joscelin III of Edessa becomes titular Count of Edessa after the death of his father Joscelin II of Edessa.

1160

- November. Raynald of Châtillon is imprisoned by the governor of Aleppo during a plundering raid. Baldwin III of Jerusalem declares Bohemond III of Antioch as ruler, but Constance of Antioch successfully resists the move.

1161

- 11 September. Melisende of Jerusalem dies and is buried at the Abbey of Saint Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat.[150]

1162

1163

- 18 February. Amalric of Jerusalem becomes king upon the death of Baldwin III of Jerusalem eight days earlier.[151]

- September. Amalric begins the first of his Crusader invasions of Egypt on the premise that the Fatimids had not paid their yearly tribute.[152]

- (Date unknown). Amalric of Jerusalem leads an army that defeats Nūr-ad-Din at the Battle of al-Buqaia.[153]

- (Date unknown). Bohemond III of Antioch reaches the age of majority. The Antiochene barons make an alliance with Thoros II of Armenia and force Constance of Antioch to leave Antioch. Bohemond III becomes prince of Antioch.

The Rise of Saladin

[edit]Saladin was a Kurdish officer in Nūr-ad-Din's army who would unite both Syria and Egypt under his rule, forming the Ayyubid dynasty that would threaten the very existence of the Franks in the Holy Land.[154]

1164

- Summer. Amalric of Jerusalem begins his second Crusader invasion of Egypt.[155]

- 12 August. Nūr-ad-Din defeats a large Crusader army at the Battle of Harim (Battle of Artah), taking many of the leaders prisoner, including Raymond III of Tripoli, Bohemond III of Antioch, Joscelin III of Edessa and Konstantinos Kalamanos.[155]

- August–October. Shawar forms an alliance with Amalric of Jerusalem to attack Shirkuh at Bilbeis. The ensuing stalemate caused both Amalric and Shirkuh to withdraw from Egypt.[156]

- (Date unknown). Aimery of Limoges sends a letter to Louis VII of France describing the events in the Crusader states.[157]

1165

- (Date unknown). Bohemund III of Antioch and Thoros II of Armenia, held in captivity by Nūr-ad-Din, are ransomed by Manuel I Komnenos.[158]

- (Date unknown). Alexander III calls for a new crusade to the Holy Land.[159]

1166

1167

- January. Amalric of Jerusalem begins his third Crusader invasion of Egypt.[160]

- 18 March.The Syrian forces of Shirkuh and Saladin defeat those of Amalric of Jerusalem at the Battle of al-Babein.[161]

- Late March – early August. Shirkuh retires to Alexandria and is besieged by Shawar and Amalric of Jerusalem. Shirkuh leaves the city in the hands of Saladin, who then enters into a truce with Amalric.[162]

1168

- 1 October. William of Tyre negotiates and alliance between Amalric of Jerusalem and Manuel I Komnenos against Egypt.[163]

- 4 November. Amalric of Jerusalem takes the city of Bilbeis after a three-day siege.[164]

1169

- 22 March. Shirkuh dies of natural causes and is succeeded by his nephew Saladin.[165]

- 21 May. The Moors, supported by Ferdinand II of León, defeat Afonso I of Portugal and Gerald the Fearless at the Siege of Badajoz.[166]

- 15 October. A joint Frankish-Byzantine force begins the fourth Crusader invasion of Egypt.[167]

- 20 October – 13 December. Amalric of Jerusalem and Andronikos Kontostephanos conduct the unsuccessful Siege of Damietta.[167]

1170

- December. Saladin invades Jerusalem besieges Darum on the Mediterranean coast. Amalric of Jerusalem withdraws his Templar garrison from Gaza to assist him in defending Darum. Saladin raises the siege and marches on Gaza, but is forced to retreat[168].

1171

- September. Saladin becomes the effective ruler of Egypt, beginning the Ayyubid sultanate.[169]

1172

1173

- Late. Raymond III of Tripoli is ransomed after eight years of captivity.[170]

1174

- 11 July. Amalric of Jerusalem dies and his son Baldwin IV of Jerusalem is coronated as king at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre king on 15 July.[171]

- August. Raymond III of Tripoli claims the regency of Baldwin IV of Jerusalem.[172]

1175

- 8 June. William of Tyre becomes archbishop of Tyre.[173]

- 22 July. Before leaving Syria, Saladin again attacks the Assassins and agrees to a truce with Baldwin IV of Jerusalem.[174]

1176

- Early. With Baldwin IV of Jerusalem's leprosy confirmed, embassies are sent to William Longsword to offer him the hand of Sibylla of Jerusalem to secure succesion in the kingdom.[175]

- May. Bohemond III of Antioch makes an alliance with Zengid Aleppo for the release of Joscelin III of Courtenay and Raynald of Châtillon.[176]

- 15 July. Baldwin IV of Jerusalem comes of age and Raymond III of Tripoli steps down as regent. The truce between Raymond and Saladin ends.[177]

- Mid-August. Baldwin IV of Jerusalem and Raymond III of Tripoli raid the Beqaa Valley near Damascus, later defeating a Damascene army led by Turan Shah at Ayn al-Jarr.[178]

- Late August. Joscelin III of Courtenay is appointed seneschal of Jerusalem.[179]

- November. Sibylla of Jerusalem and William Longsword marry.[180]

- (Date unknown). William Longsword and Raynald of Châtillon give a land grant to the Order of Mountjoy.[181]

1177

- Spring. Raynald of Châtillon marries Stephanie of Milly, lady of Oultrejordain, and is granted the castles at Kerak and Montréal as well as the lordship of Hebron.[l][182]

- June. William Longsword dies leaving Sibylla of Jerusalem pregnant with the future Baldwin V of Jerusalem.[183]

- 2 August. Philip I of Flanders lands in the Holy Land and is offered the regency of Baldwin IV of Jerusalem. He refuses and Raynald of Châtillon becomes regent to the king.[176]

- 25 November. Baldwin IV of Jerusalem routs Saladin's army at the Battle of Montgisard.[184]

1178

- March. Saladin marches to relive Harem, under siege by Philip I of Flanders.[185]

- August. The Franks break the truce and attack Hama. They are driven off by Saladin.[185]

The Fall of Jerusalem

[edit]The Ayyubid dynasty under Saladin began their attacks against the Kingdom of Jerusalem, eventually leading the the fall of Jerusalem in 1187.[186]

1179

- March. Hugh III of Burgundy agrees to marry Sibylla of Jerusalem, planning to depart for Jerusalem early the next year.[187]

- 10 April. The Ayyubid army of Farrukh Shah defeats that of Baldwin IV of Jerusalem at the Battle of Banias. Constable Humphrey II of Toron dies of wounds inflicted in the battle on 22 April.[187]

- April. The castle at Le Chaselet is completed and handed over to the Knights Templar.[188]

- June. Saladin defeats Baldwin IV of Jerusalem at the Battle of Marj Ayyun.[189]

- 23–30 August. Saladin defeats Baldwin IV of Jerusalem at the Siege of Jacob's Ford, destroying the castle at Le Chaselet.[190]

1180

- 20 April. Sibylla of Jerusalem marries Guy of Lusignan.[191]

- May. Representatives of Baldwin IV of Jerusalem and Saladin sign a two-year truce (which excludes Tripoli).[192]

- Spring. Baldwin of Ibelin returns to Jerusalem to discoved the Sibylla of Jerusalem has remarried.[193]

- 16 October. Heraclius of Jerusalem named Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem.[194]

1181

- Summer. Raynald of Châtillon breaks the truce with Saladin by attacking two caravans between Syria and Egypt. Saladin complains to Baldwin IV of Jerusalem and demands compensation.[195]

1182

- May–August. Saladin fights the inconclusive Battle of Belvoir Castle as part of his campaign against the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[196]

1183

- February. Raynald of Châtillon's fleet attacks Muslim targets on the Red Sea, including the Egyptian fortress on Pharaoh's Island, before being destroyed by a fleet dispatched by al-Adil.[197]

- 30 September – 6 October. A force led by Guy of Lusignan skirmished with Saladin's army at the Battle of al-Fule with inconclusive results.[198]

- Early November – 4 December. Saladin conducts the unsuccessful Siege of Kerak, interrupting the marriage ceremony of Isabella I of Jerusalem and Humphrey IV of Toron, the stepson of Raynald of Châtillon.[199]

- November. Baldwin IV of Jerusalem removes Guy of Lusignan from his executive regency.[200]

- 20 November. Baldwin V of Jerusalem becomes co-king with his ailing uncle Baldwin IV of Jerusalem.[201]

1184

1185

- Early. Raymond III of Tripoli is appointed regent to the kingdom and Baldwin V of Jerusalem by the dying Baldwin IV of Jerusalem.[202]

- 25 November. Urban III becomes pope.[203]

1186

- August. Baldwin IV of Jerusalem dies.[171]

- Late summer. Sibylla of Jerusalem and Guy of Lusignan are coronated as queen and king of Jerusalem.[204]

- October. Raymond III of Tripoli and Baldwin of Ibelin refuse to pay homage to the king and queen.[205]

- Later. Guy of Lusignan marches against Tiberias, a fief of Raymond III of Tripoli who invites Saladin to intervene.[206]

1187

- Early. Raynald of Châtillon attacks a large convoy en route to Cairo.[m][206]

- 1 May. A Frankish force led by Gerard de Ridefort and Roger de Moulins are decisively defeated by Saladin's general Gökböri at the Battle of Cresson.[208]

- 2 July. Saladin attacks Tiberias defended by Eschiva of Bures, wife of Raymond III of Tripoli. She surrenders the city three days later.[209]

- 3–4 July. A Crusader force led by Guy of Lusignan and Raynald of Châtillon is defeated by Saladin and Gökböri at the Battle of Hattin. Guy is captured and Raynald is executed.[210]

- 20 September – 2 October. Saladin conquest over the Franks is complete with the Siege of Jerusalem. The city was surrendered by Balian of Ibelin with Christians allowed to leave after paying a ransom.[211]

- 20 October. Urban III dies and is succeeded by Gregory VIII on 25 October.[n][213]

- 29 October. Gregory VIII issues the bull Audita tremendi calling for the Third Crusade.[214]

- (Date unknown). Bohemond IV of Antioch becomes count of Tripoli.

Third Crusade

[edit]The Third Crusade was led by Frederick Barbarossa and Richard the Lionheart, and was followed shortly by the Crusade of 1197.[215]

1188

- January. Henry II of England and Philip II of France take the cross at Gisors.[216][217]

- 27 March. Frederick Barbarossa takes the cross at the Curia Christi held in Mainz.[218]

- Spring. Saladin releases Guy of Lusignan from captivity.[219]

- 26 May. Barbarossa sends Saladin an ultimatum to withdraw from the lands he had taken.[220]

- 20–22 July. Bohemond III of Antioch is defeated by Saladin at the Siege of Laodicea.[221]

- 26–29 July. Saladin defeats the Knights Hospitaller at the Siege of Sahyun Castle.[222]

- 5–9 August. The Principality of Antioch is defeated by the forces of Saladin at the Siege of al-Shughur.[223]

- 20–23 August. Shortly thereafter, Saladin successfully executes the Siege of Bourzey Castle.[223]

- November. The Franks abandon Kerak Castle to the Ayybuids after the Siege of Kerak.[224]

- Early November – 6 December. Saladin and his brother al-Adil I capture the Templar castle after the Siege of Safed.[225]

1189

- 9 January. After over a year, Saladin is successful in his Siege of Belvoir Castle.[226]

- 11 May. The Third Crusade begins, with Frederick Barbarossa and his forces departing Regensburg.[227]

- 6 July. Henry II of England dies and is succeeded by his son Richard the Lionheart, who was crowned on 3 September and continued his father's plans for the crusade.[228]

- August. Guy of Lusignan marches to Tyre but is refused entry by Conrad of Montferrat.

- 28 August. Guy of Lusignan begins the Siege of Acre.[229]

- 1 September. The Holy Roman Empire fleet arrives at Acre.[230]

1190

- April. After a long siege, Muslim forces under Saladin capture Beaufort Castle from Reginald of Sidon.[231]

- 18 May. Barbarossa led an army commanded by Frederick of Swabia, Děpolt II and Géza of Hungary to defeat the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Iconium.[232]

- 10 June. Frederick Barbarossa drowns while crossing the Saleph River and his army returns to Germany.[218]

- 25 July. Sibylla of Jerusalem and her two daughters die and her sister Isabella I of Jerusalem becomes queen.[233]

- 7 August. Richard the Lionheart leaves for Sicily, arriving at Messina on 23 September. His fleet had arrived earlier, on 14 September.[234]

- 4 October. Richard the Lionheart captures Messina.[234] Tancred of Sicily agrees to a treaty in exchange for his recognition and the release of Joan of England.[235]

- Early November. The marriage of Isabella I of Jerusalem and Humphrey IV of Toron is annulled.[233]

- 24 November Isabella I of Jerusalem marries Conrad of Montferrat.[236]

1191

- 30 March. Celestine III becomes pope.[237]

- 10 April. Richard the Lionheart leaves Sicily. Bad weather forces him to land in Cyprus, entering Limassol on 6 May.[238]

- 20 April. Philip II of France arrives at Acre.[238]

- 6 May. Bad weather forces the fleet of Richard the Lionheart to land at Limassol. The Conquest of Cyprus is complete by 1 June.[239]

- 12 May. Berengaria of Navarre marries Richard the Lionheart in Cyprus. She was the eldest daughter of Sancho VI of Navarre and Sancha of Castile.[240]

- 8 June. Richard the Lionheart arrives at Acre.[241]

- 12 July. Acre surrenders to the Crusaders, ending the two-year Siege of Acre.[241]

- 31 July. Philip II of France, accompanied by Conrad of Montferrat, departs to Tyre and returns to France. He leaves behind a French army under the command of Hugh III of Burgundy.[217]

- 20 August. Richard the Lionheart has the Muslim prisoners of war captured at Acre beheaded during the Massacre at Ayyadieh. In retaliation, Saladin does same to his Christian prisoners.[242]

- 7 September. Richard the Lionheart leads a Crusader army to defeat Saladin at the Battle of Arsuf.[243]

- November. The Crusader army advances on Jerusalem.[244]

- 12 December. Saladin disbands most of his army under pressure from his emirs.[245]

1192

- Before 24 April. Conrad of Montferrat (Conrad I of Jerusalem) is elected king of Jerusalem.[236]

- 28 April. Conrad of Montferrat is murdered by two Assassins.[246]

- 6 May. Henry II of Champagne marries Isabella I of Jerusalem, then pregnant with their child Maria of Montferrat. He becomes Henry I of Jerusalem.[233]

- 21 June. Enrico Dandolo becomes doge of Venice.[247]

- 8 August. In the final battle of the Third Crusade, Richard the Lionheart defeats Saladin at the Battle of Jaffa.[248]

- 2 September. Richard the Lionheart and Saladin agree to the Treaty of Jaffa. Jerusalem would remain under Muslim control, while allowing unarmed Christian pilgrims and traders to visit the city.[249]

- 9 October. Richard the Lionheart departs the Holy Land.[250]

1193

- 4 March. Saladin dies and is succeeded by his sons Al-Aziz Uthman in Egypt and Al-Afdal in Syria.[251]

1194

- October. Leo I of Armenia invites Bohemond III of Antioch to Bagras to resolve their differences. Upon Bohemond's arrival, Leon captures him and his family, and takes them to the capital of Sis.[252]

1195

- March. Henry VI of Germany announces a new crusade, later known at the Crusade of 1197.[253]

1196

1197

- March. The German forces under Henry VI of Germany begin the Crusade of 1197.[254]

- 10 September. Al-Adil I leads a force that takes the city in the Battle of Jaffa.[255]

- 10 September. Henry I of Jerusalem dies from falling out of a window at his palace in Acre. His widow, Isabella I of Jerusalem, becomes regent while the kingdom is thrown into consternation.[256]

- 22 September. The German forces of the Crusade of 1197 arrive at Acre.[257]

Fourth Crusade

[edit]The Fourth Crusade was launched to again go the Holy Land, but instead resulted in the Sack of Constantinople and the collapse of the Byzantine Empire. Shortly thereafter, the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathar heretics and the Children's Crusade began.[258]

1198

- 8 January. Innocent III becomes pope.[259]

- 2 February. Failing to take the city, the German crusaders lift the Siege of Toron and return home.[260]

- Spring. Aimery of Cyprus marries Isabella I of Jerusalem and are crowned as king and queen of Jerusalem at Acre.[261]

- July 1 Aimery of Cyprus signs a treaty with al-Adil I securing the Crusader possessions from Acre to as far as Antioch for five years and eight months.[261]

- 15 August. Innocent III issues the bull Post miserabile calling for the Fourth Crusade.[262]

1199

1200

- (Date unknown). Beatrix de Courtenay becomes titular countess of Edessa.[263]

- (Date unknown). The Livre au Roi, the earliest surviving text of the Assizes of Jerusalem, is written.[264]

1201

- March. Envoys are sent to Venice, then led by doge Enrico Dandolo, to negotiate sea transportation of the crusaders to Cairo, believed to be the best route to secure Jerusalem.[265]

- April. Bohemond III of Antioch dies, triggering the War of the Antiochene Succession.

- 24 May. Theobald III of Champagne dies and is replaced by Boniface of Montferrat as leader of the crusade that summer.[266]

1202

- May. The Crusader force gathers in Venice, but in smaller numbers that expected. Unable to pay the Venetians for the boats they built, Enrico Dandolo proposes an attack on Adriatic ports as payment.[o][267]

- Spring. Crusaders who chose to continue to the Holy Land arrive in Acre.[268]

- Later. As part of the War of the Antiochene Succession, Leo I of Armenia attacks Antioch, defended by recently arrived Crusaders. Renard of Dampierre is captured, to be held prisoner until 1233.[269]

1203

- April. The Crusaders depart for Constantinople.[270]

- 11 July – 1 August. The Crusaders are victorious after the Siege of Constantinople.[271]

1204

- 12–15 April. The Crusaders and Venetians participate in the Sack of Constantinople, essentially ending the Byzantine empire. The new Latin Empire was created under Baldwin IX of Flanders, as Baldwin I.[272]

- September–October. The Byzantine empire is formally partitioned with the signing of the Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae, creating the Frankokratia.[273]

- September. Realizing that the Fourth Crusade will not bring sufficient reinforcements to Acre, Aimery of Cyprus negotiates a six-year truce with al-Adil I.[274]

120

- 1 April. Aimery of Cyprus dies and is succeeded by Hugh I of Cyprus. Isabella I of Jerusalem is the sole ruler of Jerusalem.[275]

- April. Isabella I of Jerusalem dies and is succeeded as queen of Jerusalem by her daughter Maria of Montferrat.[276]

1206

1207

1208

1209

1210

- 3 October. John of Brienne is crowned king of Jerusalem by virtue of his marriage to Maria of Montferrat.[277]

1211

1212

- (Date unknown). Isabella II of Jerusalem becomes queen of Jerusalem after the death of her mother Maria of Montferrat.[278]

Fifth Crusade

[edit]The Fifth Crusade attacked Egypt with disastrous results.[279]

1213

- 19 April. Innocent III issues his papal bull Quia maior calling for what will become the Fifth Crusade.[280][281]

1214

1215

- 11 November. The Fourth Lateran Council endorses the Fifth Crusade.[282]

1216

- 14 February. Leo I of Armenia reconquers the Principality of Antioch and Raymond-Roupen is installed as prince.[283]

- 18 July. Honorius III becomes pope, continuing the support of the new crusade.[284]

1217

- 1 July. Forces depart France on the Fifth Crusade.[285]

- 23 August. The forces of Andrew II of Hungary depart from Split for Syria on what is known as the Crusade of Andrew II of Hungary (Hungarian Crusade), part of the Fifth Crusade.[286]

- 30 November – 7 December. The army of Andrew II of Hungary fails in their Siege of Mount Tabor against the fortress held by the Ayyubids.[286]

- 15 December. The Hungarian Crusade ends with their defeat at the Battle of Machghara by the Ayyubids.[286]

1218

- 10 January. Hugh I of Cyprus dies and is succeeded in Cyprus by his one-year old son Henry I of Cyprus.[287]

- 27 May. The first of the Crusader ships arrive in Egypt. Led by John of Brienne, other commanders include Leopold VI of Austria, Simon III of Sarrebrück, and masters Peire de Montagut, Hermann of Salza and Guérin de Montaigu.[288]

- 29 May. The Siege of Damietta begins.[289]

- 24 August. The siege engines of Oliver of Paderborn breach the main tower of Damietta which is taken is taken the next day.[289]

- 9 November. Papal delegate Pelagius Galvani arrives in Egypt and takes command of the Crusade from John of Brienne.[290]

1219

- 2 May. Leo I of Armenia dies and is succeeded by Isabella of Armenia.

- Shortly thereafter. Raymond-Roupen is ousted from Antioch and Bohemond IV is reinstated as prince of Antioch.

- May. Leopold VI of Austria returns home from the Fifth Crusade.[291]

- 29 August. After his overtures of peace were rejected, al-Kamil defeats the Crusaders under Pelagius Galvani and John of Brienne at the Battle of Fariskur.[292]

- September. Saint Francis of Assisi arrives in Egypt to negotiate with the sultan.[293]

- 5 November. The Crusaders take the city from the Ayyubids after the successful Siege of Damietta.[289]

1220

1221

- 26–28 August. In the final battle of the Fifth Crusade, the Crusader forces under Pelagius Galvani and John of Brienne are defeated by the Ayyubid forces of al-Kamil at the Battle of Mansurah.[294]

- 8 September. Pelagius Galvani surrenders and the Crusaders begin to depart Egypt. The Fifth Crusade has ended with nothing gained by the West.[295]

1222

Sixth Crusade

[edit]Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, undertook the Sixth Crusade and made significant gains with no military actions.[296]

1223

- 23 March. In a meeting between Honorius III and Frederick II and John of Brienne, preparations begin for the Sixth Crusade to recapture Jerusalem. Frederick agrees to lead the Crusade and again takes the cross.[297]

1224

1225

- 9 November. Frederick II marries Isabella II of Jerusalem, becoming king of Jerusalem.[298]

- (Date unknown). Bohemond V of Antioch marries Alice of Champagne.

1226

- 8 November. Louis IX of France becomes king after the death of his father Louis VIII of France.[299]

1227

- 19 March. Gregory IX becomes pope.[300]

- 5 July. The marriage between Bohemond V of Antioch and Alice of Champagne is annulled.

- 8 September. The forces of the Sixth Crusade depart Europe. Shortly thereafter, Frederick II is forced to return due to illness. The rest of the army, now under the command of Henry of Limburg and Gérold of Lausanne.[301]

- 29 September. Gregory IX excommunicates Frederick II for his failure to fulfil his crusading vows.[301]

- 11 November. After the death of his brother al-Muazzam Isa, al-Kamil takes control of Jerusalem. His brother al-Ashraf Musa maintains control of Syria.[302]

1228

- 4 May. Conrad II of Jerusalem becomes king of Jerusalem upon the death of his mother Isabella II of Jerusalem.

- 28 June. Gregory IX resinds his excommunication of Frederick II.[301]

- 7 September. Frederick II arrives at Acre. He sends Thomas of Accera and Balian Grenier to negotiate with the sultan al-Kamil.[303]

1229

- 18 February. The Sixth Crusade end with the signing of the Treaty of Jaffa between Frederick II and al-Kamil. Jerusalem is restored to Christian rule.[304]

- 17 March. Frederick II enters Jerusalem and crowns himself king. He departs eight days later.[305]

1230

1231

- Autumn. John of Brienne is crowned Latin Emperor.[277]

1232

1233

- (Date unknown). Bohemond V of Antioch becomes prince of Antioch and count of Tripoli.

Barons' Crusade

[edit]After the truce that ended the Sixth Crusade, a further military action known as the Barons' Crusade was launched by Theobald I of Navarre and Richard of Cornwall, returning the Kingdom of Jerusalem to its largest extent since 1187.[306]

1234

- 7 April. Theobald I of Navarre becomes king.[307]

- 17 November. Gregory IX issues the papal bull Rachel suum videns calling for a new crusade to the Holy Land. This would result in the Barons' Crusade to begin in 1239.[308]

1235

- (Date unknown). Bohemond V of Antioch marries Lucienne of Segni, a great-niece of Innocent III.

1236

1237

1238

1239

- 2 November. Theobald I of Navarre initiates the Barons' Crusade after the expiration of the ten-year treaty between the West and the Ayyubids.[309]

- 13 November. The army of Theobald I of Navarre is defeated by the Ayyubids at the Battle at Gaza.[310]

- 3 December. Theobald I of Navarre departs the Holy Land. Four days later, Damascene emir an-Nasir Dawud captures Jerusalem from the Franks but does not hold it.[310]

1240

- 8 October. The English forces of Richard of Cornwall arrive in the Holy Land.[311]

1241

- 23 April. Richard of Cornwall completes the negotiation of the treaty with Al-Salih Ismail.[306]

- 3 May. The forces of Richard of Cornwall depart Acre, ending the Barons' Crusade.[309]

1242

1243

- 25 June. Innocent IV becomes pope.[312]

1244

- 11 July – 23 August. The Khwarazmians destroy the city and its inhabitants after their successful Siege of Jerusalem.[313]

- 17–18 October. The Ayyubid army as-Salih Ayyub, reinforced with Khwarezmian mercenaries, defeat the Franksh forces at the Battle of Forbie.[314]

- Late. After a near-fatal illness, Louis IX of France takes the cross (prior to papal authorization of a crusade).[299]

Seventh Crusade

[edit]Louis IX of France launched the Seventh Crusade against Egypt, again resulting in disaster.[315]

1245

- 28 June. At the First Council of Lyon, the Seventh Crusade to the Holy Land under Louis IX of France is authorized.[316]

- October. Jean de Joinville joins the Crusade.[317]

1246

- August. As an embassy of Innocent IV, Franciscan John of Plano Carpini travels to Mongolia to meet with Güyük Khan who demands that the pope pay him homage. Upon his return at the end of 1247, John reports to Rome that the Mongols were only out for conquest.[318]

1247

- May. Dominican Ascelin of Lombardy is sent to meet the Mongol general Baiju Noyan. Baiju and Ascelin discussed an alliance against the Ayyubids.[319]

- August – 15 October. The Ayyubids defeat the Hospitallers at the Siege of Ascalon and occupy the city.[320]

1248

- 25 August. The Seventh Crusade begins when Louis IX of France leaves Paris with his queen Margaret of Provence, her sister Beatrice of Provence and two of Louis' brothers, Charles I of Anjou and Robert I of Artois.[321]

1249

- 6 June. The Crusades capture the Egyptian city after the successful Siege of Damietta.[322]

1250

- 8–11 February. Louis IX of France and his forces are defeated by the Ayyubids at the Battle of Mansurah (1250).[323]

- 6 April. In the last major battle of the Seventh Crusade, the Franks are totally defeated by the Ayyubids at the Battle of Fariskur. Louis IX of France and much of his force is captured.[324]

- 6 May. Louis IX of France is freed and later goes to Acre where he works to free his captive force. He finally returns home in 1254.[315]

1251

- (Date unknown). A popular crusade known as the Shepherds' Crusade is formed to free Louis IX of France from captivity. The crusade does not advance out of France.[325]

- (Date unknown). Plaisance of Antioch, the daughter of Bohemond V of Antioch and Lucienne of Segni, marries Henry I of Cyprus.

1252

- 17 January. Bohemond VI of Antioch becomes prince of Antioch and count of Tripoli upon the death of his father Bohemond V of Antioch.

1253

1254

- 24 April. Louis IX of France departs from Acre, ending the Seventh Crusade.[315]

- 21 May. Conradin becomes the nominal king of Jerusalem upon the death of Conrad II of Jerusalem.[326]

1256

1257

1258

1259

1260

- 18–24 January. Mongol leader Hulagu Khan, supported by forces of Bohemond VI of Antioch and Hethum I of Armenia, conquer the city in their Siege of Aleppo.[327]

1261

- 24 July. The Empire of Nicaea is successful in their Reconquest of Constantinople, ousting the Latin Empire and restoring the Byzantine Empire.[328]

- 15 August 1261. Michael VIII Palaiologos begins the Palaiologan dynasty to rule the Byzantine Empire until 1453.[329]

- 29 August. Urban IV becomes pope.[330]

1263

1265

- 5 February. Clement IV become pope.[331]

- 8 February. Abaqa becomes second to rule the Mongol Ilkhanate, after the death of his father Hulagu Khan.[332]

- 21 March – 29 April. The Mamluks under Baibars defeat the Knights Hospitaller in battle, resulting in the Fall of Arsuf.[333]

- (Date unknown). Baibars destroys the city of Caesarea Maritima.[334]

Eighth Crusade

[edit]Louis IX of France again takes the cross, launching Eighth Crusade against Tunis. His death marked the end of the crusade.[315]

1266

- Mid-January. Clement IV calls for a new expedition to the Holy Land which will become the Eighth Crusade.[335]

- 13 June – 23 July. Baibars destroys the contingent of Knights Templar at the Siege of Safed.[336]

- 24 August. Baibars conquers Cilician Armenia at the Battle of Mari.[337]

1267

- 2 March. German knights depart on the Crusade of 1267 in response to the papal bull Expansis in cruce issued in August 1265. The crusade accomplished nothing.[338]

- 24 March. Louis IX of France takes the cross to go on the Eighth Crusade.[339]

1268

- May. Baibars is successful in his Siege of Antioch.[340]

- 29 October. Conradin is beheaded on orders of Charles I of Anjou. and is succeeded by Hugh III of Cyprus as king of Cyprus and Jerusalem.[341]

1269

- 24 September 1269. Hugh III of Cyprus is crowned king of Jerusalem. The claim of Maria of Antioch to the throne is rejected.[342]

1270

- 1 July. The Eighth Crusade begins as the forces of Louis IX of France depart for Tunis.[343]

- 17 August. Philip of Montfort killed by Assassins on the orders of Baibars.[344]

- 25 August. Louis IX of France dies while on the Eighth Crusade and succeeded by his son Philip III of France.[345]

- 20 October. Lord Edward and his forces depart for Tunis. They will arrive too late for the Eighth Crusade and proceed to the Holy Land.[346]

- 21 October. Hethum I of Armenia abdicates and is succeeded by his son Leo II of Armenia.[347]

- 1 November. The Treaty of Tunis is signed, ending the Eighth Crusade. Philip III of France, Charles I of Anjouand Theobald II of Navarre signed for the Latin Christians and sultan Muhammad I al-Mustansir for Tunis.[348]

Lord Edward's Crusade

[edit]English forces en route to the Eighth Crusade arrived too late and launched Lord Edward's Crusade in the Holy Land, the last major Western offensive there.[349]

1270

- 18 November. Lord Edward and his forces arrive in Sardinia.[346]

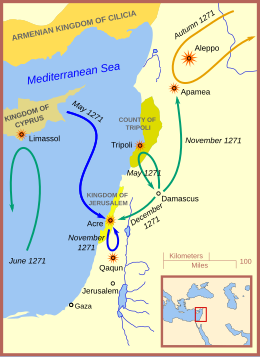

1271

- Winter–Spring. Baibars besieges Safita in February, then takes Krak des Chevaliers, Gibelacar and Tripoli.[350]

- 13 March – 8 April. Baibars captures the Hospitaller stonghold with the Fall of Krak des Chevaliers.[351]

- 9 May. Lord Edward and his forces arrive in Acre.[352]

- Late May. Baibars offers Bohemond VI of Antioch a ten-year truce after the Siege of Tripoli.[353]

- 1 September. Gregory X is elected pope and preaches new crusade in coordination with the Mongols.[354]

1272

- 22 May. Lord Edward's Crusade, the last major crusade to the Holy Land, ends inconclusively with a ten-year truce with Baibars. Edward is attacked by an Assassin the next month.[355]

- 20 November. Edward I of England becomes king after the death of his father Henry III three days earlier.[356]

Decline and Fall of the Crusader States

[edit]The Mamluks under Baibars, later Qalawun, continued their onslaught on the Franks in the Levant, leading to the Fall of Tripoli in 1289 and, two years later, their successful Siege of Acre.[346] The West would never recover Jerusalem.[357]

1273

- Early. Haymo Létrange puts Beirut and their ruler Isabella of Beirut under the protection of Baibars.[358]

1274

- Early. Gregory X receives reports on the failure of the crusades including Gilbert of Tournai's Collectio de scandalis ecclesiae, Bruno of Olomouc's Relatio de statu ecclesiae in regno alemaniae, and Humbert of Romans'Opus tripartitum.[359]

- 7 May – 17 July. The Second Council of Lyon discusses reconquest of the Holy Land.[360] Representatives of the Ilkhanate attend and the Union of Churches approved.[361]

1275

- March. Baibars continues his campaign against Armenia and demands the return of the Christian half of Latakia.[362]

- 4 June. Hugh III of Cyprus negotiates a truce with Baibars that protects Latakia in exchange for an annual tribute.[362]

- (Date unknown). Bohemond VII of Tripoli becomes count of Tripoli and titluar prince of Antioch upon the death of his father Bohemond VI of Antioch.

1276

- October. The Knights Templar purchase La Fauconnerie (La Féve), omitting to secure the consent of Hugh III of Cyprus.[363]

- October. Hugh III of Cyprus relocates from Acre to Cyprus.[364]

1277

- 18 March. Charles I of Anjou secures the disputed title of king by purchasing Maria of Antioch's claim to the throne of Jerusalem.[365]

- 25 November. Nicholas III is elected pope after the death of John XXI on 20 May 1277.[366]

- 1 July. Baibars dies and is succeeded by sons Barakah and then Solamish.[367]

1278

- January. Charles I of Anjou is crowned king of Jerusalem at Acre and is recognized by the kingdom's barons. He appoints Roger of San Severino as his representative.[368]

1279

- November. Qalawun becomes Mamluk sultan after deposing Solamish.[369]

1280

1281

- 22 February. Martin IV is elected pope.[370]

- 3 May. Qalawun renews the truce with the Kingdom of Jerusalem for another ten years.[371]

- 16 July. Bohemond VII of Tripoli agrees to Qalawun's truce for the County of Tripoli.[371]

- 29 October. The Mamluks defeat a coalition of Mongols, Armenians and Hospitallers at the second Battle of Homs.[372]

1282

- January. Bohemond VII of Tripoli kills Guy II Embriaco, alienating the Genoese.[373]

1283

- Late July. Hugh III of Cyprus sails for Acre, arriving in August to lukewarm reception.[374]

1284

- 4 March. Hugh III of Cyprus dies in Tyre and his son John I of Cyprus crowned king of Jerusalem two months later. John is recognized as king only in Beirut and Tyre.[375]

1285

- 7 January. Charles I of Anjou dies and is succeeded by his son Charles II of Naples, who also claims the crown of Jerusalem.[376]

- 28 March. Martin IV dies and Honorius IV is elected pope on 2 April.[377]

- 25 April – 24 May. Mamluks capture of the Hospitaller castle at Marqab.[378]

1286

- 24 June. Henry II of Cyprus returns to Acre.[379]

- 29 July. Angevin bailli Odo Poilechien, loyal to Charles II of Naples, hands the citadel over to Henry II at the insistence of the three military orders.[380]

- 15 August. Henry II of Cyprus is crowned king of Jerusalem at Tyre. A few weeks later, he returns to Cyprus after appointing Philip of Ibelin as regent.[381]

1287

- 20 April. Qalawun takes Latakia, claiming it is not covered by the truce of 1281.[382]

- 19 October. Bohemond VII of Tripoli dies and succeeded by his sister Lucia of Tripoli as countess.[383]

1288

- Early. Lucia of Tripoli and her husband Narjot de Toucy arrive in Acre.[383]

- 22 February. Nicholas IV becomes pope, immediately supports a crusade to the Holy Land.[384]

1289

- 27 March – 26 April. Mamluk sultan Qalawan begins the Siege of Tripoli, causing the fall of one of the last remnants of the kingdom in the Levant a month later.[385]

- Easter. Arghun sends Buscarello de Ghizolfi to Italy and France to announce that he intends to invade Syria in 1291.[386]

- May. Fort Nephin and Le Boutron are occupied by Qalawan. Peter Embriaco is allowed to retain his estates in Tripoli.[387]

- September. Jean de Grailly is sent to the West to appeal for help.[388]

- (Date unknown). Leo II of Armenia dies and is succeeded by his son Hethum II of Armenia.[389]

1290

- 10 February. Nicholas IV calls for a crusade against the Mamluks.[390]

- August. Venetian and Aragonese crusaders arrive at Acre, and instigate a massacre of Muslims in the city.[391]

- Fall. The Egyptian army mobilizes towards Acre.[392]

- 4 November. Qalawun leaves Cairo for Syria, en route to Acre. He dies six days later.[393]

- 10 November. Qalawun's son al-Ashraf Khalil becomes Mamluk sultan.[394]

1291

- 4 April – 18 May. Crusaders lose their last stronghold in the Holy Land when Mamluk sultan Khalil successfully executes the Siege of Acre.[395][396]

- May–July. Tyre, Sidon, Beirut surrender to Mamluks.[397]

- 3–14 August. Templar castles Tortosa and Château Pèlerin evacuated, but retain their presence on the island fortress of Ruad. The Fall of Ruad to the Mamluks on 26 September 1302 marks ends the presence of the Crusaders in the mainland of the Levant.[398]

See also

[edit]- Chronologies of the Crusades

- Historians and histories of the Crusades

- Medieval Jerusalem

- Saladin in Egypt

Notes

[edit]- ^ The leaders of the First Crusade were Hugh of Vermandois, Godfrey of Bouillon, Baldwin of Boulogne, Bohemond of Taranto, Tancred, Robert of Flanders, Raymond of Saint-Gilles, Adhemar of Le Puy, Stephen of Blois and Robert Curthose.

- ^ The leaders of the People's Crusade were Peter the Hermit, Walter Sans Avoir, Emicho, Folkmar and Gottschalk.

- ^ Baldwin of Boulogne was the first Count of Edessa. He was later the first king of Jerusalem as his brother Godfrey of Bouillon chose not to take the title of king.

- ^ Bohemond of Taranto was the first Prince of Antioch as Bohemond I of Antioch.

- ^ Godfrey of Bouillon took the titles of prince (princeps) and advocate or defender of the Holy Sepulchre (advocatus Sancti Sepulchri).[27]

- ^ Crusaders who joined the Reconquista after returning from the Holy Land include: Gaston IV of Béarn, Rotrou III of Perche, Centule II of Bigorre, William IX of Aquitaine, Bernard Ato IV and William V of Montpellier.[30]

- ^ Baldwin I of Jerusalem was the first of the kings and queens of Jerusalem.

- ^ The Turkish commanders at Mersivan included Kilij Arslan, Gazi Gümüshtigin and Ridwan. The Crusaders were led by Raymond of Saint-Gilles and Stephen of Blois.

- ^ The Crusaders had two seperate forces remaining after Mersivan. One under William II of Nevers and a second under William IX of Aquitaine and Hugh of Vermandois.

- ^ Bertrand of Toulouse was the first count of Tripoli after the capture of the city. Raymond of Saint-Gilles was declared count in 1102.

- ^ The First Council of the Lateran ruled that the crusades to the Holy Land and the Reconquista of Spain were of equal standing, granting equal privileges.[78]

- ^ The lordship of Hebron was under royal domain until 1161 when Hebron was merged with the lordship of Oultrejordain under Philip of Milly, father of Stephanie of Milly. Baldwin IV of Jerusalem granted the lordship to Raynald of Châtillon in 1177 shortly after his marriage to Stephanie.

- ^ The Estoire d'Eracles incorrectly claims that Saladin's sister was also among the prisoners taken by Raynald of Châtillon when he seized the caravan.[207]

- ^ Urban III allegedly collapsed when hear the news of the loss of Jerusalem, but William of Newburgh believed that the pope died before he heard the news.[212]

- ^ The leaders of the Fourth Crusade were Boniface of Montferrat, Enrico Dandolo, Theobald III of Champagne, Baldwin of Flanders, Louis of Blois, Hugh IV of Saint-Pol, Conrad of Halberstadt, Martin of Pairis andConon de Béthune

References

[edit]- ^ Baldwin 1969a, The First Hundred Years.

- ^ Runciman 1992, The First Crusade.

- ^ Robert Somerville (2011). Pope Urban II's Council of Piacenza. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Duncalf 1969a, pp. 220–252, The Councils of Piacenza and Clermont.

- ^ a b Richard Urban Butler (1912). "Pope Bl. Urban II". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Dana Carleton Munro (1906). The Speech of Pope Urban II. At Clermont, 1095, The American Historical Review, Vol. 11, No. 2, pgs. 231–242.

- ^ Steven Runciman (1949). The First Crusaders' Journey across the Balkan Peninsula. Byzantion, 19, 207–221.

- ^ Duncalf 1969b, pp. 253–279, The First Crusade: Clermont to Constantinople.

- ^ Ernest Barker (1911). "Peter the Hermit". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 294–296.

- ^ Conor Kostick (2008). The Leadership of the First Crusade. In: The Social Structure of the First Crusade. Brill, pgs. 243–270.

- ^ Asbridge 2004, pp. 101–103, The Battle of Civetot.

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 142–145, Hugh of Vermandois.

- ^ John 2018, The Army of Godfrey of Bouillon.

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 154–158, Bohemond's arrival at Constantinople.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 116–118, Robert II, Count of Flanders.

- ^ Louis René Bréhier (1911). "Raymond IV of Saint-Gilles". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 164–166, Robert of Normandy and Steven of Blois.

- ^ Runciman 1969a, pp. 288–292, Siege of Niceae.

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 183–184, Battle of Dorylaeum.

- ^ Asbridge 2000, pp. 15–34, Siege of Antioch.

- ^ Runciman 1969a, pp. 300–304, Baldwin at Edessa.

- ^ Runciman 1951, pp. 214–215, Capture of the City.

- ^ Asbridge 2004, pp. 232–240, The Great Battle of Antioch.

- ^ Asbridge 2000, pp. 42–44, The early formation of the Principality of Antioch.

- ^ James A. Brundage (1959). “Adhemar of Puy: The Bishop and His Critics.” Speculum, Vol. 34, No. 2, pgs. 201–212.

- ^ Runciman 1969b, pp. 333–337, The Siege of Jerusalem.

- ^ Murray 2000, pp. 63–93, Godfrey of Bouillon as Ruler of Jerusalem.

- ^ a b Ernest Barker (1911). "Godfrey of Bouillon". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 172–173.

- ^ Asbridge 2004, p. 322, Arnulf of Chocques.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1997, pp. 165–166, First Crusaders and the Reconquista.

- ^ Asbridge 2004, pp. 323–327, The Battle of Ascalon.

- ^ James Francis Loughlin (1911). "Pope Paschal II". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 56, Daimbert of Pisa.

- ^ a b Ernest Barker (1911). "Tancred (crusader)". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 394–395.

- ^ Louis René Bréhier (1910). "Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1291)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Fink 1969, p. 380, Battle of Melitene.

- ^ a b Ernest Barker (1911). "Baldwin II (King of Jerusalem)". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 246.

- ^ a b Ernest Barker (1911). "Baldwin I (King of Jerusalem)". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 245–246.

- ^ Cate 1969, pp. 343–367, The Crusade of 1101.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 23–25, Battle of Mersivan.

- ^ Cate 1969, pp. 361–362, The Battles at Heraclea Cybistra.

- ^ a b Michael Brett (2019). The Battles of Ramla, 1099–1108. In: The Fatimids and Egypt. Taylor & Francis Group.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 87, First Siege of Acre.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 128–129, Siege of Jaffa.

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 63, Castle at Mount Pilgrim.

- ^ a b Jonathan Riley-Smith (1983). “The Motives of the Earliest Crusaders and the Settlement of Latin Palestine, 1095-1100.” The English Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 389, pgs. 721–736.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 38–39, Bohemond's Release.

- ^ Fink 1969, pp. 389–390, Battle of Harran.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 43, Baldwin's First Captivity.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 88.

- ^ Asbridge 2000, p. 57, Battle of Artah.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 88–89, Third Battle of Ramla.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 108–111, Jawali Saqawa at Mosul.

- ^ Sigurd I Magnusson, King of Norway. Britannica, 1998.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 111–112, Release of Baldwin.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 50–51, Treaty of Devol.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 93, Siege of Beirut.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 74, Siege of Sidon.

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 62, Krak des Chevaliers.

- ^ Ernest Barker (1911). "Bohemund II". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 135–136.

- ^ a b Runciman 1952, pp. 122–124, Mawdud's failure.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 124, Vasil Dgha.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 112, Arnoulf of Chocques.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 107, Pie postulatio voluntatis.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 126–127, Battle of Sennabra.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 101–103, Baldwin I remarries.

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 23–25, Krak de Montreal.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 132–133, Frankish Victory at Tel-Danith.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 128–129, The Fall of Vasil Dgha.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 34, Capture of Azaz.

- ^ James MacCaffrey (1908). "Pope Callistus II". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Morton 2018, pp. 83–122, The Battle of the Field of Blood.

- ^ Morton 2018, pp. 114–118, The Second Battle of Tell Danith.

- ^ Thomas Andrew Archer and Walter Alison Phillips (1911). "Templars". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 591–600.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 131, The Council of Nablus.

- ^ a b Jonathan Riley-Smith (1986). "The Venetian Crusade of 1122–1124". In: The Italian Communes in the Crusading Kingdom of Jerusalem.

- ^ John L. La Monte (1942). “The Lords of Le Puiset on the Crusades.” Speculum, Vol. 17, No. 1, pgs. 100–118.

- ^ Roberto Marin-Guzmán (1992). "Crusade in Al-Andalus: The Eleventh Century formation of the Reconquista as an Ideology". Islamic Studies. Vol. 31, No. 3, pgs. 287–318.

- ^ First Lateran Council (2016). From: Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, ed. Norman P. Tanner.

- ^ Alan V. Murray (1994). Baldwin II and his nobles: Baronial factionalism and dissent in the kingdom of Jerusalem, 1118-1134. Nottingham Medieval Studies, Vol. 38, pgs. 60–85.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 166, Battle of Ibelin.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 170–172, Ransom of King Baldwin.

- ^ a b Runciman 1952, p. 172, Siege of Aleppo.

- ^ a b Runciman 1952, pp. 172–174, Battle of Azaz.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 174, Battle of Tel es-Saqhab.

- ^ a b Gibb 1969b, pp. 449–462, Zengi and the Fall of Edessa.

- ^ Bosworth 2004, p. 189, The Bûrids, 1104–1154.

- ^ El-Azhari 2016, pp. 24–25, Zengi at Aleppo.

- ^ Margaret Tranovich (2011). Melisende of Jerusalem: The World of a Forgotten Crusader Queen. East & West Publishing.

- ^ Nicholson 1969, pp. 429–431, The Damascus Crusade.

- ^ Francis Mershman (1910). "Pope Innocent II". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Runciman 1989, pp. 182–183, Death of Bohemond II.

- ^ Nicholson 1969, p. 431, Battle of al-Atharib.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Mélusine. Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 101.

- ^ Ernest Barker (1911). "Fulk, King of Jerusalem". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 293–294.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 41, Isma'il captures Banias.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 41, Alice of Antioch.

- ^ El-Azhari 2016, p. 69, Battle of Rafaniyya.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 190–193, The revolt of Hugh II du Puiset.

- ^ Nicholson 1969, pp. 435–436, Zengi's campaign against Antioch.

- ^ William Hunt (1891). "Henry I". In Dictionary of National Biography. 25. London. pgs. 436–451.

- ^ Bernard Hamilton (1984). Ralph of Domfront, Patriarch of Antioch (1135-1140). Nottingham Medieval Studies. 28: 1–21

- ^ Nicholson 1969, pp. 436–437, Battle of Qinnasrin.

- ^ Nicholson 1969, p. 438, Battle of Ba'rin.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 204–205, Surrender of Montferrand.

- ^ Steve Tibble (2020). The Hinterland Strategy: 1125–1153. Yale University Press.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 216–217, Siege of Shaizar.

- ^ Barber 1994, pp. 56–57, Omne Datum Optimum.

- ^ a b Nicholson 1969, pp. 442–443, Banias and Damascus.

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 78, Krak des Chevaliers.

- ^ a b Ernest Barker (1911). "Baldwin III". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 246–247.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 225–246, The Fall of Edessa.

- ^ Barber 1994, p. 58, Milites Templi.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 192, The Fall of Saruj.

- ^ James Francis Loughlin (1909). "Pope Eugene III". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Barber 1994, p. 58, Militia Dei.

- ^ Berry 1969, pp. 463–512, The Second Crusade.

- ^ Berry 1969, pp. 466–467, Quantum praedecessores.

- ^ Father Marie Gildas (1907). "St. Bernard of Clairvaux". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Thomas Andrew Archer (1889). "Eleanor (1122–1204)". In Dictionary of National Biography. 17. London. pgs. 175–178.

- ^ Giles Constable (1953). The Second Crusade as seen by Contemporaries. Traditio Vol. 9, pg. 255.

- ^ Gibb 1969b, p. 462, The Second Siege of Edessa.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Conrad III. Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 966–967.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Frederick I, Roman Emperor. Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 45–46.

- ^ a b Lock 2006, pp. 46–47, The French contingent.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 241–242, The Franks break with Unur.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 156, Alfonso Jordan.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 266–267, The Germans cross into Asia.

- ^ Nicolle 2009, p. 47, Battle of Dorylaeum.

- ^ Lock 2006, pp. 48–49, The German contingent.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 326, Battle of Ephesus.

- ^ Phillips 2007, p. 198, Battle of the Meander.

- ^ C. W. David (1932). “The Authorship of the De Expugnatione Lyxbonensi.” Speculum, Vol. 7, No. 1, pgs. 50–57.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 272, The French at Anatolia.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 330–331, Council of Acre.

- ^ Phllips 2007, pp. 252–254, Siege of Tortosa.

- ^ Siege of Damascus, 1148. Britannica.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 278–288, Fiasco at Damascus.

- ^ Gibb 1969c, pp. 513–527, The Career of Nūr-ad-Din.

- ^ N. Elisséeff (1993). Nūr al-Dīn Maḥmūd b. Zankī. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam New Edition Online.

- ^ Alex Mallett (2013). “The Battle of Inab”. Journal of Medieval History 39, No. 1, pgs. 48–60.

- ^ Venning & Frankopan 2015, pp. 136–137, Battle of Aintab.

- ^ Henri Paul Eydoux (1981). "Le château franc de Turbessel." Bulletin Monumental 139 No. 4, pgs 229–232.

- ^ Lewis 1969, p. 120, Murder of Raymond II of Tripoli.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 338–340, The Capture of Ascalon.

- ^ Michael Ehrlich (2019). "The Battle of ʿAin al-Mallaha, 19 June 1157". Journal of Military History 83(1): 31–42.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 350–351, Battle of Butaiha.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 352–353, The Emperor in Antioch.

- ^ James Francis Loughlin (1907). "Pope Alexander III". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, pg. 287.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 359–360, Melisende of Tripoli.

- ^ Ernest Barker (1911). "Amalric". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 778–779.

- ^ Eric Böhme (2022). Legitimising the Conquest of Egypt: The Frankish Campaign of 1163 Revisited. The Expansion of the Faith, Vol. 14, pgs. 269 –280.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 367, Nūr-ad-Din defeated at Krak.

- ^ Gibb 1969d, pp. 563–589, The Rise of Saladin.

- ^ a b Runciman 1952, pp. 369–370, Disaster at Artah.

- ^ Gibb 1969c, pp. 523–524, The Siege of Bilbeis.

- ^ "Letter from Aymeric, Patriarch of Antioch, to Louis VII, King of France (1164)". De Re Militari. 2013.

- ^ Runciman 1952, p. 370, Ransom of Bohemund III.

- ^ Venning & Frankopan 2015, p. 153, Alexander III calls for a crusade.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 56, Crusader invasions of Egypt.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 372–374, Frankish ambassadors at Cairo.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 374–376, Saladin besieged in Alexandria.

- ^ Baldwin 1969b, p. 555, Alliance with Jerusalem and Byzantium.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 380–381, Amalric advances on Cairo.

- ^ Winifred Frances Peck (1911). "Saladin". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ McMurdo 1888, pp. 224–226, Siege of Badajoz.

- ^ a b Baldwin 1969b, pp. 556–558, Siege of Damietta.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 317–318, Saladin invades Gaza.

- ^ R. S. Humphreys (2011). "Ayyubids". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. III, Fasc. 2, pgs. 164-167.

- ^ Ernest Barker (1911). "Raymund of Tripoli". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg .935.

- ^ a b Ernest Barker (1911). "Baldwin IV". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 247

- ^ Marshall W. Baldwin (1936). Raymond III of Tripolis and the Fall of Jerusalem (1140-1187). Princeton University Press.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). William, Archbishop of Tyre. Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 677.

- ^ Gibb 1969d, p. 569, Saladin leaves Syria.

- ^ Hamilton 2005, p. 109, William of Montferrat.

- ^ a b Bernard Hamilton (1978 ). The Elephant of Christ: Reynald of Châtillon. Studies in Church History 15, pgs. 97–108.

- ^ Hamilton 2005, pp. 84–108, The King's minority.

- ^ Lane-Poole 1898, p. 151, Turan Shah.

- ^ Robert L. Nicholson (1973). Joscelyn III and the Fall of the Crusader States 1134-1199. Brill.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 410–412, Sibylla's first marriage.

- ^ Joseph F. O’Callaghan (1969). “Hermandades between the Military Orders of Calatrava and Santiago during the Castilian Reconquest, 1158-1252.” Speculum, Vol. 44, No. 4, pgs. 609–618.

- ^ Hamilton 2005, p. 117, Raynald of Châtillon marries.

- ^ Baldwin 1969c, p. 593, Death of William Longspear.

- ^ Lane-Poole 1898, pp. 154–155, Battle of Montgisard.

- ^ a b Gibb 1969d, pp. 571–572, Saladin returns to Syria.

- ^ Baldwin 1969c, pp. 590–621, The Decline and Fall of Jerusalem, 1174-1189.

- ^ a b Runciman 1952, pp. 418–420, Death of Humphrey of Toron.

- ^ Jones, Dan (2017). The Templars: The Rise and Spectacular Fall of God's Holy Warriors. pp. 178–186.

- ^ Joshua J. Mark (2023). Battle of Marj Ayyun. World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ Baldwin 1969c, p. 595, Siege of Jacob's Ford.

- ^ Baldwin 1969c, pp. 596–597, Marriage of Sibylla and Guy of Lusignan.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 420–422, Two years' truce.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 422–424, Sibylla and Baldwin of Ibelin.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 424–426, The Patriarch Heraclius.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 430–432, Raynald of Châtillon breaks the truce.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 432–434, Death of as-Salih.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 436–438, Raynald's Red Sea Expedition.

- ^ Baldwin 1969c, pp. 599–600, Battle of al-Fūlah.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 440–442, The marriage at Kerak.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 438–440, Guy quarrels with the King.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Baldwin V. Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 247.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 442–444, King Baldwin IV's will.