Steampunk

Steampunk is a subgenre of science fiction that incorporates retrofuturistic technology and aesthetics inspired by, but not limited to, 19th-century industrial steam-powered machinery.[1][2][3] Steampunk works are often set in an alternative history of the Victorian era or the American frontier, where steam power remains in mainstream use, or in a fantasy world that similarly employs steam power.

Steampunk features anachronistic technologies or retrofuturistic inventions as people in the 19th century might have envisioned them — distinguishing it from Neo-Victorianism[4] — and is likewise rooted in the era's perspective on fashion, culture, architectural style, and art.[5] Such technologies may include fictional machines like those found in the works of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne.[6] Other examples of steampunk contain alternative-history-style presentations of such technology as steam cannons, lighter-than-air airships, analog computers, or such digital mechanical computers as Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine.[7][8]

Steampunk may also incorporate additional elements from the genres of fantasy, horror, historical fiction, alternate history, or other branches of speculative fiction, making it often a hybrid genre.[9] As a form of speculative fiction, it explores alternative futures or pasts but can also address real-world social issues.[10] The first known appearance of the term steampunk was in 1987, though it now retroactively refers to many works of fiction created as far back as the 1950s or earlier.[11] A popular subgenre is Japanese steampunk, consisting of steampunk-themed manga and anime.[12]

Steampunk also refers to any of the artistic styles, clothing fashions, or subcultures that have developed from the aesthetics of steampunk fiction, Victorian-era fiction, art nouveau design, and films from the mid-20th century.[13] Various modern utilitarian objects have been modded by individual artisans into a pseudo-Victorian mechanical "steampunk" style, and a number of visual and musical artists have been described as steampunk.[14]

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]

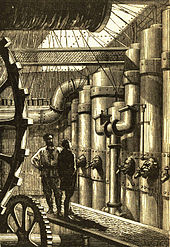

Steampunk is influenced by and often adopts the style of the 19th-century scientific romances of Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, Mary Shelley, and Edward S. Ellis's The Steam Man of the Prairies.[15] Several more modern works of art and fiction significant to the development of the genre were produced before the genre had a name. Titus Alone (1959), by Mervyn Peake, is widely regarded by scholars as the first novel in the genre proper,[16][17][18] while others point to Michael Moorcock's 1971 novel The Warlord of the Air,[19][20][21] which was heavily influenced by Peake's work. The film Brazil (1985) was an early cinematic influence, although it can also be considered a precursor to the steampunk offshoot dieselpunk.[22] The Adventures of Luther Arkwright was an early (1970s) comic version of the Moorcock-style mover between timestreams.[23][24]

In fine art, Remedios Varo's paintings combine elements of Victorian dress, fantasy, and technofantasy imagery.[25][page needed] In television, one of the earliest manifestations of the steampunk ethos in the mainstream media was the CBS television series The Wild Wild West (1965–69), which inspired the later film.[15][8]

Origin of the term

[edit]Although many works now considered seminal to the genre were published in the 1960s and 1970s, the term "steampunk" originated largely in the 1980s[26] as a tongue-in-cheek variant of "cyberpunk". It was coined by science fiction author K. W. Jeter,[27] who was trying to find a general term for works by Tim Powers (The Anubis Gates, 1983), James Blaylock (Homunculus, 1986), and himself (Morlock Night, 1979, and Infernal Devices, 1987) — all of which took place in a 19th-century (usually Victorian) setting and imitated conventions of such actual Victorian speculative fiction as H. G. Wells' The Time Machine. In a letter to science fiction magazine Locus,[26] printed in the April 1987 issue, Jeter wrote:

Dear Locus,

Enclosed is a copy of my 1979 novel Morlock Night; I'd appreciate your being so good as to route it to Faren Miller, as it's a prime piece of evidence in the great debate as to who in "the Powers/Blaylock/Jeter fantasy triumvirate" was writing in the "gonzo-historical manner" first. Though of course, I did find her review in the March Locus to be quite flattering.

Personally, I think Victorian fantasies are going to be the next big thing, as long as we can come up with a fitting collective term for Powers, Blaylock and myself. Something based on the appropriate technology of the era; like "steam-punks," perhaps....

Modern steampunk

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (November 2020) |

While Jeter's Morlock Night and Infernal Devices, Powers' The Anubis Gates, and Blaylock's Lord Kelvin's Machine were the first novels to which Jeter's neologism would be applied, the three authors gave the term little thought at the time.[7]: 48 They were far from the first modern science fiction writers to speculate on the development of steam-based technology or alternative histories. Keith Laumer's Worlds of the Imperium (1962) and Ronald W. Clark's Queen Victoria's Bomb (1967) apply modern speculation to past-age technology and society.[30][page needed] Michael Moorcock's Warlord of the Air (1971)[21] is another early example. Harry Harrison's novel A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (1973) portrays Britain in an alternative 1973, full of atomic locomotives, coal-powered flying boats, ornate submarines, and Victorian dialogue. The Adventures of Luther Arkwright (mid-1970s) was one of the first steampunk comics.[31] In February 1980, Richard A. Lupoff and Steve Stiles published the first "chapter" of their 10-part comic strip The Adventures of Professor Thintwhistle and His Incredible Aether Flyer.[32] In 2004, one anonymous author described steampunk as "Colonizing the Past so we can dream the future."[33]

The first use of the word "steampunk" in a title was in Paul Di Filippo's 1995 Steampunk Trilogy,[21] consisting of three short novels: "Victoria", "Hottentots", and "Walt and Emily", which, respectively, imagine the replacement of Queen Victoria by a human/newt clone; an invasion of Massachusetts by Lovecraftian monsters, drawing its title from the historic racial taxonomy "hottentot"; and a love affair between Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

Japanese steampunk

[edit]Japanese steampunk consists of steampunk manga comics and anime productions from Japan.[12] Steampunk elements have consistently appeared in mainstream manga since the 1940s, dating back to Osamu Tezuka's epic science-fiction trilogy consisting of Lost World (1948), Metropolis (1949) and Nextworld (1951). The steampunk elements found in manga eventually made their way into mainstream anime productions starting in the 1970s, including television shows such as Leiji Matsumoto's Space Battleship Yamato (1974) and the 1979 anime adaptation of Riyoko Ikeda's manga Rose of Versailles (1972). Influenced by 19th-century European authors such as Jules Verne, steampunk anime and manga arose from a Japanese fascination with an imaginary fantastical version of old Industrial Europe, linked to a phenomenon called akogare no Pari ("the Paris of our dreams"), comparable to the West's fascination with an "exotic" East.[34]

The most influential steampunk animator was Hayao Miyazaki, who was creating steampunk anime since the 1970s, starting with the television show Future Boy Conan (1978).[34] His manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1982) and its 1984 anime film adaptation also contained steampunk elements. Miyazaki's most influential steampunk production was the Studio Ghibli anime film Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), which became a major milestone in the genre and has been described by The Steampunk Bible as "one of the first modern steampunk classics."[35] Archetypal steampunk elements in Laputa include airships, air pirates, steam-powered robots, and a view of steam power as a limitless but potentially dangerous source of power.[34]

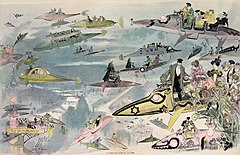

The success of Laputa inspired Hideaki Anno and Studio Gainax to create their first hit production, Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water (1990), a steampunk anime show which loosely adapts elements from Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, with Captain Nemo making an appearance.[34] Based on a concept by Miyazaki, Nadia was influential on later steampunk anime such as Katsuhiro Otomo's anime film Steamboy (2004).[36] Disney's animated steampunk film Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001)[15] was influenced by anime, particularly Miyazaki's works and possibly Nadia.[37][38] Other popular Japanese steampunk works include Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli anime film Howl's Moving Castle (2004),[34] Sega's video game and anime franchise Sakura Wars (1996) which is set in a steampunk version of Meiji/Taishō era Japan,[34] and Square Enix's manga and anime franchise Fullmetal Alchemist (2001).[12]

Relationships to retrofuturism, DIY craft and making

[edit]

Steampunk used to be confused with retrofuturism.[39] Indeed, both sensibilities recall "the older but still modern eras in which technological change seemed to anticipate a better world, one remembered as relatively innocent of industrial decline." For some scholars, retrofuturism is considered a strand of steampunk, one that looks at alternatives to historical imagination and usually created with the same kinds of social protagonists and written for the same type of audiences.[40]

One of steampunk's most significant contributions is the way in which it mixes digital media with traditional handmade art forms. As scholars Rachel Bowser and Brian Croxall put it, "the tinkering and tinker-able technologies within steampunk invite us to roll up our sleeves and get to work re-shaping our contemporary world."[41] In this respect, steampunk bears much in common with DIY craft and bricolage artmaking.[42]

Art, entertainment, and media

[edit]Art and design

[edit]

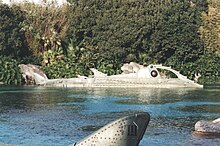

Many of the visualisations of steampunk have their origins with, among others, Walt Disney's film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954),[43] including the design of the story's submarine the Nautilus, its interiors, and the crew's underwater gear; and George Pal's film The Time Machine (1960), especially the design of the time machine itself. This theme is also carried over to Six Flags Magic Mountain and Disney parks, in the themed area the "Screampunk District" at Six Flags Magic Mountain and in the designs of The Mysterious Island section of Tokyo DisneySea theme park and Disneyland Paris' Discoveryland area.[citation needed]

Aspects of steampunk design emphasise a balance between form and function.[44] In this, it is like the Arts and Crafts Movement. But John Ruskin, William Morris, and the other reformers in the late nineteenth century rejected machines and industrial production. In contrast, steampunk enthusiasts present a "non-luddite critique of technology". In dutch amusement park De Efteling, there is a dive coaster themed to a steampunk Victorian haunted goldmine called Baron 1898.[45]

Various modern utilitarian objects have been modified by enthusiasts into a pseudo-Victorian mechanical "steampunk" style.[24][46] Examples include computer keyboards and electric guitars.[47] The goal of such redesigns is to employ appropriate materials (such as polished brass, iron, wood, and leather) with design elements and craftsmanship consistent with the Victorian era,[21][48] rejecting the aesthetic of industrial design.[44]

In 1994, the Paris Metro station at Arts et Métiers was redesigned by Belgian artist Francois Schuiten in steampunk style, to honor the works of Jules Verne. The station is reminiscent of a submarine, sheathed in brass with giant cogs in the ceiling and portholes that look out onto fanciful scenes.[49][50]

The artist group Kinetic Steam Works[51] brought a working steam engine to the Burning Man festival in 2006 and 2007.[52] The group's founding member, Sean Orlando, created a Steampunk Tree House (in association with a group of people who would later form the Five Ton Crane Arts Group[53]) that has been displayed at a number of festivals.[54][55] The Steampunk Tree House is now permanently installed at the Dogfish Head Brewery in Milton, Delaware.[56]

The Neverwas Haul is a three-story, self-propelled mobile art vehicle built to resemble a Victorian house on wheels. Designed by Shannon O'Hare, it was built by volunteers in 2006 and presented at the Burning Man festival from 2006 through 2015.[57] When fully built, the Haul propelled itself at a top speed of 5 miles per hour and required a crew of ten people to operate safely. Currently, the Neverwas Haul makes her home at Obtainium Works, an "art car factory" in Vallejo, CA owned by O'Hare and home to several other self-styled "contraptionists".[58]

In May–June 2008, multimedia artist and sculptor Paul St George exhibited outdoor interactive video installations linking London and Brooklyn, New York, in a Victorian era-styled telectroscope.[59][60] Utilizing this device, New York promoter Evelyn Kriete organised a transatlantic wave between steampunk enthusiasts from both cities,[61] prior to White Mischief's Around the World in 80 Days steampunk-themed event.[62]

In 2009, for Questacon, artist Tim Wetherell created a large wall piece that represented the concept of the clockwork universe. This steel artwork contains moving gears, a working clock, and a movie of the moon's terminator in action. The 3D moon movie was created by Antony Williams.[63]

Steampunk became a common descriptor for homemade objects sold on the craft network Etsy between 2009 and 2011,[64] though many of the objects and fashions bear little resemblance to earlier established descriptions of steampunk. Thus the craft network may not strike observers as "sufficiently steampunk" to warrant its use of the term. Comedian April Winchell, author of the book Regretsy: Where DIY Meets WTF, cataloged some of the most egregious and humorous examples on her website "Regretsy".[65] The blog was popular among steampunks and even inspired a music video that went viral in the community and was acclaimed by steampunk "notables".[66]

From October 2009 through February 2010, the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, hosted the first major exhibition of steampunk art objects, curated and developed by New York artist and designer Art Donovan,[67] who also exhibited his own "electro-futuristic" lighting sculptures, and presented by Dr. Jim Bennett, museum director.[68] From redesigned practical items to fantastical contraptions, this exhibition showcased the work of eighteen steampunk artists from around the globe. The exhibit proved to be the most successful and highly attended in the museum's history and attracted more than eighty thousand visitors. The event was detailed in the official artist's journal The Art of Steampunk, by curator Donovan.[69]

In November 2010, The Libratory Steampunk Art Gallery was opened by Damien McNamara in Oamaru, New Zealand. Created from papier-mâché to resemble a large cave and filled with industrial equipment from yesteryear, rayguns, and general steampunk quirks, its purpose is to provide a place for steampunkers in the region to display artwork for sale all year long. A year later, a more permanent gallery, Steampunk HQ, was opened in the former Meeks Grain Elevator Building across the road from The Woolstore, and has since become a notable tourist attraction for Oamaru.[70][71][72]

In 2012, the Mobilis in Mobili: An Exhibition of Steampunk Art and Appliance made its debut. Originally located at New York City's Wooster Street Social Club (itself the subject of the television series NY Ink), the exhibit featured working steampunk tattoo systems designed by Bruce Rosenbaum, of ModVic and owner of the Steampunk House,[73] Joey "Dr. Grymm" Marsocci,[47] and Christopher Conte.[74] with different approaches.[43] "[B]icycles, cell phones, guitars, timepieces and entertainment systems"[74] rounded out the display.[47] The opening night exhibition featured a live performance by steampunk band Frenchy and the Punk.[75]

The stills at The Oxford Artisan Distillery are nicknamed "Nautilus" and "Nemo", named after the submarine and its captain in the Jules Verne 1870 science fiction novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas. They were built in copper by South Devon Railway Engineering using a steampunk style.[76]

Fashion

[edit]

Steampunk fashion has no set guidelines but tends to synthesize modern styles with influences from the Victorian era. Such influences may include bustles, corsets, gowns, and petticoats; suits with waistcoats, coats, top hats[77] and bowler hats (themselves originating in 1850 England), tailcoats and spats; or military-inspired garments. Steampunk-influenced outfits are usually accented with several technological and "period" accessories: timepieces, parasols, flying/driving goggles,[78] and ray guns. Modern accessories like cell phones or music players can be found in steampunk outfits, after being modified to give them the appearance of Victorian-era objects. Post-apocalyptic elements, such as gas masks, ragged clothing, and tribal motifs, can also be included. Aspects of steampunk fashion have been anticipated by mainstream high fashion, the Lolita and aristocrat styles, neo-Victorianism, and the Romantic Goth subculture.[23][79][80]

In 2005, Kate Lambert, known as "Kato", founded the first steampunk clothing company, "Steampunk Couture",[81] mixing Victorian and post-apocalyptic influences. In 2013, IBM predicted, based on an analysis of more than a half million public posts on message boards, blogs, social media sites, and news sources, "that 'steampunk,' a subgenre inspired by the clothing, technology and social mores of Victorian society, will be a major trend to bubble up and take hold of the retail industry".[82][83] Indeed, high fashion lines such as Prada,[84] Dolce & Gabbana, Versace, Chanel,[85] and Christian Dior[83] had already been introducing steampunk styles on the fashion runways.

In episode 7 of Lifetime's Under the Gunn reality series, contestants were challenged to create avant-garde "steampunk chic" looks.[86] America's Next Top Model tackled steampunk fashion in a 2012 episode where models competed in a steampunk-themed photo shoot, posing in front of a steam train while holding a live owl.[87][unreliable source]

Literature

[edit]

In 1988, the first version of the science fiction tabletop role-playing game Space: 1889 was published. The game is set in an alternative history in which certain now discredited Victorian scientific theories were probable and led to new technologies. Contributing authors included Frank Chadwick, Loren Wiseman, and Marcus Rowland.[88]

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's novel The Difference Engine (1990) is often credited with bringing about widespread awareness of steampunk.[8][89] The novel applies the principles of Gibson and Sterling's cyberpunk writings to an alternative Victorian era where Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage's proposed steam-powered mechanical computer, which Babbage called a difference engine (a later, more general-purpose version was known as an Analytical Engine), was actually built, and led to the dawn of the Information Age more than a century "ahead of schedule". This setting was different from most steampunk settings in that it takes a dim and dark view of this future, rather than the more prevalent utopian versions.[citation needed]

Nick Gevers's original anthology Extraordinary Engines (2008) features newer steampunk stories by some of the genre's writers, as well as other science fiction and fantasy writers experimenting with neo-Victorian conventions. A retrospective reprint anthology of steampunk fiction was released, also in 2008, by Tachyon Publications. Edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer and appropriately entitled Steampunk, it is a collection of stories by James Blaylock, whose "Narbondo" trilogy is typically considered steampunk; Jay Lake, author of the novel Mainspring, sometimes labeled "clockpunk";[90] the aforementioned Michael Moorcock; as well as Jess Nevins, known for his annotations to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (first published in 1999).[91]

Younger readers have also been targeted by steampunk themes, by authors such as Philip Reeve and Scott Westerfeld.[92] Reeve's quartet Mortal Engines is set far in Earth's future where giant moving cities consume each other in a battle for resources, a concept Reeve coined as Municipal Darwinism. Westerfeld's Leviathan trilogy is set during an alternate First World War fought between the "clankers" (Central Powers), who use steam technology, and "darwinists" (Allied Powers), who use genetically engineered creatures instead of machines.[93]

"Mash-ups" are also becoming increasingly popular in books aimed at younger readers, mixing steampunk with other genres. Stefan Bachmann's The Peculiar duology was labeled a "steampunk fairytale," and imagines steampunk technology as a means to stave off an incursion of faeries in Victorian England.[94] Suzanne Lazear's Aether Chronicles series also mixes steampunk with faeries, and The Unnaturalists, by Tiffany Trent, combines steampunk with mythological creatures and alternate history.[95]

Self-described author of "far-fetched fiction" Robert Rankin has incorporated elements of steampunk into narrative worlds that are both Victorian and re-imagined contemporary. In 2009, he was made a Fellow of the Victorian Steampunk Society.[96]

The comic book series Hellboy, created by Mike Mignola, and the two Hellboy films featuring Ron Perlman and directed by Guillermo del Toro, all have steampunk elements.[97] In the comic book and the first (2004) film, Karl Ruprecht Kroenen is a Nazi SS scientist who has an addiction to having himself surgically altered, and who has many mechanical prostheses, including a clockwork heart. The character Johann Krauss is featured in the comic and in the second film, Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008), as an ectoplasmic medium (a gaseous form in a partly mechanical suit). This second film also features the Golden Army itself, which is a collection of 4,900 mechanical steampunk warriors.[98]

Steampunk settings

[edit]Alternative world

[edit]

Since the 1990s, the application of the steampunk label has expanded beyond works set in recognisable historical periods, to works set in fantasy worlds that rely heavily on steam- or spring-powered technology.[8] One of the earliest short stories relying on steam-powered flying machines is "The Aerial Burglar" of 1844.[99] An example from juvenile fiction is The Edge Chronicles by Paul Stewart and Chris Riddell.

Fantasy steampunk settings abound in tabletop and computer role-playing games. Notable examples include Skies of Arcadia,[100] Rise of Nations: Rise of Legends,[101] and Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura.[15]

One of the first steampunk novels set in a Middle-earth-like world was the Forest of Boland Light Railway by BB, about gnomes who build a steam locomotive. Fifty years later, Terry Pratchett wrote the Discworld novel Raising Steam, about the ongoing industrial revolution and railway mania in Ankh-Morpork.

The gnomes and goblins in World of Warcraft also have technological societies that could be described as steampunk,[102] as they are vastly ahead of the technologies of men, but still run on steam and mechanical power.

The Dwarves of the Elder Scrolls series, described therein as a race of Elves called the Dwemer, also use steam-powered machinery, with gigantic brass-like gears, throughout their underground cities. However, magical means are used to keep ancient devices in motion despite the Dwemer's ancient disappearance.[103]

The 1998 game Thief: The Dark Project, as well as the other sequels including its 2014 reboot, feature heavy steampunk-inspired architecture, setting, and technology.

Amidst the historical and fantasy subgenres of steampunk is a type that takes place in a hypothetical future or a fantasy equivalent of our future involving the domination of steampunk-style technology and aesthetics. Examples include Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro's The City of Lost Children (1995), Turn A Gundam (1999–2000), Trigun,[104] and Disney's film Treasure Planet (2002). In 2011, musician Thomas Dolby heralded his return to music after a 20-year hiatus with an online steampunk alternate fantasy world called the Floating City, to promote his album A Map of the Floating City.[15]

American West

[edit]Another setting is "Western" steampunk, which overlaps with both the weird West and science fiction Western subgenres. One of the earliest steampunk books set in America was The Steam Man of the Prairies by Edward S. Ellis. Recent examples include the TV show The Wild Wild West and the movie adaption Wild Wild West, the Italian comics about Magico Vento,[105] and Devon Monk's Dead Iron.[106]

Fantasy and horror

[edit]Kaja Foglio introduced the term "Gaslight Romance",[7]: 78 gaslamp fantasy, which John Clute and John Grant define as "steampunk stories ... most commonly set in a romanticised, smoky, 19th-century London, as are Gaslight Romances. But the latter category focuses nostalgically on icons from the late years of that century and the early years of the 20th century—on Dracula, Jekyll and Hyde, Jack the Ripper, Sherlock Holmes and even Tarzan—and can normally be understood as combining supernatural fiction and recursive fantasy, though some gaslight romances can be read as fantasies of history."[9] Author/artist James Richardson-Brown[107] coined the term steamgoth to refer to steampunk expressions of fantasy and horror with a "darker" bent.

Post-apocalyptic

[edit]Mary Shelley's The Last Man, set near the end of the 21st century after a plague had brought down civilization, was probably the ancestor of post-apocalyptic steampunk literature. Post-apocalyptic steampunk is set in a world where some cataclysm has precipitated the fall of civilization and steam power is once again ascendant, such as in Hayao Miyazaki's post-apocalyptic anime Future Boy Conan (1978, loosely based on Alexander Key's The Incredible Tide (1970)),[104] where a war fought with superweapons has devastated the planet. Robert Brown's novel, The Wrath of Fate (as well as much of Abney Park's music) is set in a Victorianesque world where an apocalypse was set into motion by a time-traveling mishap. Cherie Priest's Boneshaker series is set in a world where a zombie apocalypse happened during the Civil War era. The Peshawar Lancers by S.M. Stirling is set in a post-apocalyptic future in which a meteor shower in 1878 caused the collapse of industrialized civilization. The movie 9 (which might be better classified as "stitchpunk" but was largely influenced by steampunk)[108] is also set in a post-apocalyptic world after a self-aware war machine ran amok. Steampunk Magazine even published a book called A Steampunk's Guide to the Apocalypse, about how steampunks could survive should such a thing actually happen.

Victorian

[edit]

In general, this category includes any recent science fiction that takes place in a recognizable historical period (sometimes an alternate history version of an actual historical period) in which the Industrial Revolution has already begun, but electricity is not yet widespread, "usually Britain of the early to mid-nineteenth century or the fantasized Wild West-era United States",[109] with an emphasis on steam- or spring-propelled gadgets. The most common historical steampunk settings are the Victorian and Edwardian eras, though some in this "Victorian steampunk"[110] category are set as early as the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and as late as the end of World War I.

Some examples of this type include the novel The Difference Engine,[111] the comic book series League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the Disney animated film Atlantis: The Lost Empire,[15] Scott Westerfeld's Leviathan trilogy,[112] and the roleplaying game Space: 1889.[15] The anime film Steamboy (2004) is another example of Victorian steampunk, taking place in an alternate 1866 where steam technology is far more advanced than reality.[113] Some, such as the comic series Girl Genius,[15] have their own unique times and places despite partaking heavily of the flavor of historic settings. Other comic series are set in a more familiar London, as in the Victorian Undead, which has Sherlock Holmes, Doctor Watson, and others taking on zombies, Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde, and Count Dracula, with advanced weapons and devices. Another example of this genre is the Tunnels novels by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams. These are set in the modern day, but with an underground Victorian world that is working to overthrow the world above. Detective graphic novel series Lady Mechanika is set in an alternative Victorian-like world.

Karel Zeman's film The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958) is a very early example of cinematic steampunk. Based on Jules Verne novels, Zeman's film imagines a past that never was, based on those novels.[114] Other early examples of historical steampunk in cinema include Hayao Miyazaki's anime films such as Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986) and Howl's Moving Castle (2004), which contain many archetypal anachronisms characteristic of the steampunk genre.[115][116]

"Historical" steampunk usually leans more towards science fiction than fantasy, but a number of historical steampunk stories have incorporated magical elements as well. For example, Morlock Night, written by K. W. Jeter, revolves around an attempt by the wizard Merlin to raise King Arthur to save the Britain of 1892 from an invasion of Morlocks from the future.[8]

Paul Guinan's Boilerplate, a "biography" of a robot in the late 19th century, began as a website that garnered international press coverage when people began believing that Photoshop images of the robot with historic personages were real.[117] The site was adapted into the illustrated hardbound book Boilerplate: History's Mechanical Marvel, which was published by Abrams in October 2009.[118] Because the story was not set in an alternative history, and in fact contained accurate information about the Victorian era,[119] some[specify] booksellers referred to the tome as "historical steampunk".

East Asia

[edit]Fictional settings inspired by East Asian rather than Western history, especially those inspired by Chinese history, have been called "silkpunk". The term originated with the author Ken Liu,[120] who defined it as "a blend of science fiction and fantasy [that] draws inspiration from classical East Asian antiquity", with a "technology vocabulary (...) based on organic materials historically important to East Asia (bamboo, paper, silk) and seafaring cultures of the Pacific (coconut, feathers, coral)", rather than the brass and leather associated with steampunk. Liu used the term to describe his Dandelion Dynasty series, which began in 2015.[121] Other works described as silkpunk include Neon Yang's Tensorate series of novellas, which began in 2017.[122] Lyndsie Manusos of Book Riot has argued that the genre does "not fit in a direct analogy with steampunk. Silkpunk is technology and poetics. It is engineering and language."[123]

Music

[edit]

Steampunk music is very broadly defined. Abney Park's lead singer Robert Brown defined it as "mixing Victorian elements and modern elements". There is a broad range of musical influences that make up the steampunk sound, from industrial dance and world music[80] to folk rock, dark cabaret to straightforward punk,[124] Carnatic[125] to industrial, hip-hop to opera (and even industrial hip-hop opera),[126][127] darkwave to progressive rock, barbershop to big band.

Joshua Pfeiffer (of Vernian Process) is quoted as saying, "As for Paul Roland, if anyone deserves credit for spearheading Steampunk music, it is him. He was one of the inspirations I had in starting my project. He was writing songs about the first attempt at manned flight, and an Edwardian airship raid in the mid-80s long before almost anyone else ..."[128] Thomas Dolby is also considered one of the early pioneers of retro-futurist (i.e., Steampunk and Dieselpunk) music.[129][130] Amanda Palmer was once quoted as saying, "Thomas Dolby is to Steampunk what Iggy Pop was to Punk!"[131]

Steampunk has also appeared in the work of musicians who do not specifically identify as steampunk. For example, the music video of "Turn Me On", by David Guetta and featuring Nicki Minaj, takes place in a steampunk universe where Guetta creates human androids. Another music video is "The Ballad of Mona Lisa", by Panic! at the Disco, which has a distinct Victorian steampunk theme. A continuation of this theme has been used throughout the 2011 album Vices & Virtues, in the music videos, album art, and tour set and costumes. In addition, the album Clockwork Angels (2012) and its supporting tour by progressive rock band Rush contain lyrics, themes, and imagery based around steampunk. Similarly, Abney Park headlined the first "Steamstock" outdoor steampunk music festival in Richmond, California, which also featured Thomas Dolby, Frenchy and the Punk, Lee Presson and the Nails, Vernian Process, and others.[130]

The music video for the Lindsey Stirling song "Roundtable Rival", has a Western steampunk setting.

Television and films

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958) and The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1962), both directed by Karel Zeman, have steampunk elements. The 1965 television series The Wild Wild West, as well as the 1999 film of the same name, features many elements of advanced steam-powered technology set in the Wild West time period of the United States. Two Years' Vacation (or The Stolen Airship) (1967) directed by Karel Zeman contains steampunk elements.

The BBC series Doctor Who also incorporates steampunk elements. Several storylines can be classed as steampunk, most notably The Evil of the Daleks (1966), wherein Victorian scientists invent a time travel device using mirrors and static electricity.[132] During season 14 of the show (in 1976), the formerly futuristic looking interior set was replaced with a Victorian-styled wood-panel and brass affair.[133] In the 1996 American co-production, the TARDIS interior was re-designed to resemble an almost Victorian library with the central control console made up of an eclectic array of anachronistic objects. Modified and streamlined for the 2005 revival of the series, the TARDIS console continued to incorporate steampunk elements, including a Victorian typewriter and gramophone, for many years.

Dinner for Adele (1977) directed by Oldřich Lipský involves steampunk contraptions. The 1979 film Time After Time has Herbert George "H.G." Wells following a surgeon named John Leslie Stevenson into the future, as John is suspected of being Jack the Ripper. Both separately use Wells's time machine to travel.

The Mysterious Castle in the Carpathians, (1981) directed by Oldřich Lipský, contains steampunk elements.[134] The 1982 American TV series Q.E.D. is set in Edwardian England, stars Sam Waterston as Professor Quentin Everett Deverill (from whose initials, by which he is primarily known, the series title is derived, initials which also stand for the Latin phrase quod erat demonstrandum, which translates as "which was to be demonstrated"). The Professor is an inventor and scientific detective, in the mold of Sherlock Holmes. The plot of the Soviet film Kin-dza-dza! (1986) centers on a desert planet, depleted of its resources, where an impoverished dog-eat-dog society uses steampunk machines, the movements and functions of which defy Earthly logic.

In making his 1986 Japanese film Castle in the Sky, Hayao Miyazaki was heavily influenced by steampunk culture, the film featuring various airships and steampowered contraptions as well as a mysterious island that floats through the sky, accomplished not through magic as in most stories, but instead by harnessing the physical properties of a rare crystal—analogous to the lodestone used in the Laputa of Swift's Gulliver's Travels—augmented by massive propellers, as befitting the Victorian motif.[135] The first "Wallace & Gromit" animation A Grand Day Out (1989) features a space rocket in the steampunk style.[citation needed]

The second half of Back to the Future III (1990) gradually evolves into steampunk.

The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr., a 1993 Fox Network TV science fiction-Western set in the 1890s, features elements of steampunk as represented by the character Professor Wickwire, whose inventions were described as "the coming thing".[136] The short-lived 1995 TV show Legend, on UPN, set in 1876 Arizona, features such classic inventions as a steam-driven "quadrovelocipede", trigoggle and night-vision goggles (à la teslapunk), and stars John de Lancie as a thinly disguised Nikola Tesla.[citation needed]

Alan Moore's and Kevin O'Neill's 1999 The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen graphic novel series (and the subsequent 2003 film adaption) greatly popularised the steampunk genre.[79]

Steamboy (2004) is a Japanese animated action film directed and co-written by Katsuhiro Otomo (Akira). It is a retro science-fiction epic set in a steampunk Victorian England. It features steamboats, trains, airships and inventors. The 2004 film Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events contains steampunk-esque elements such as costumes and vehicle interiors. The 2007 Syfy miniseries Tin Man incorporates a considerable number of steampunk-inspired themes into a reimagining of L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Despite leaning more towards Gothic influences, the "parallel reality" of Meanwhile, City, within the 2009 film Franklyn contains many steampunk themes, such as costumery, architecture, minimal use of electricity (with a preference for gaslight), and absence of modern technology (such as there being no motorised vehicles or advanced weaponry, and the manual management of information without computers).

The 2009–2014 Syfy television series Warehouse 13 features many steampunk-inspired objects and artifacts, including computer designs created by steampunk artisan Richard Nagy, a.k.a. "Datamancer".[137] The 2010 episode of the TV series Castle entitled "Punked" (first aired October 11, 2010) prominently features the steampunk subculture and uses Los Angeles-area steampunks (such as the League of STEAM) as extras. The 2011 film The Three Musketeers has many steampunk elements, including gadgets and airships.

The Legend of Korra, a 2012–2014 Nickelodeon animated series, incorporates steampunk elements in an industrialized world with East Asian themes. The Penny Dreadful (2014) television series is a Gothic Victorian fantasy series with steampunk props and costumes.

The 2013–2014 ABC3 game show Steam Punks!, sees Paul Verhoeven playing The Inquisitor, who helps teams complete multiple challenges who have become trapped in a bizarre world controlled by an evil genius named The Machine.[138]

The 2015 GSN reality television game show Steampunk'd features a competition to create steampunk-inspired art and designs which are judged by notable steampunks Thomas Willeford, Kato, and Matthew Yang King (as Matt King).[139] Based on the work of cartoonist Jacques Tardi, April and the Extraordinary World (2015) is an animated movie set in a steampunk Paris. It features airships, trains, submarines, and various other steam-powered contraptions. Tim Burton's 2016 film Alice Through the Looking Glass features steampunk costumes, props, and vehicles.

Japanese anime Kabaneri of the Iron Fortress (2016) features a steampunk zombie apocalypse.

The American fantasy animated sitcom, Disenchantment, created by Matt Groening for Netflix, features a steampunk country named Steamland, led by an odd industrialist named Alva Gunderson voiced by Richard Ayoade, first appears in the season 1 episode, "The Electric Princess."[140][141][a] The country is portrayed as driven by logic and is egalitarian, governed by science, rather than magic, as is the case for Dreamland, where the protagonist, Princess Bean, is from.[142] The country has cars, automatic lights, submarines, and other modern technologies, all of which are steam-powered, and references to Groening's other series, Futurama.[143][144] Steamland appears in three episodes of the show's second season,[b] showing an explorers club as part of the country's high society, flying zeppelins, and robots with light bulbs for heads that chase the protagonists through the streets.[145][146] Some even argued that Steamland is "dieselpunk-inspired."[147]

The 2023 film Poor Things has been noted for its "steampunk-infused" production design.[148]

Video games

[edit]A variety of styles of video games[149] have used steampunk settings.

Steel Empire (1992), a shoot 'em up game originally released as Koutetsu Teikoku on the Sega Mega Drive console in Japan, is considered to be the first steampunk video game. Designed by Yoshinori Satake and inspired by Hayao Miyazaki's anime film Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), Steel Empire is set in an alternate timeline dominated by steam-powered technology. The commercial success of Steel Empire, both in Japan and the West, helped propel steampunk into the video game market, and had a significant influence on later steampunk games. The most notable steampunk game it influenced is Final Fantasy VI (1994), a Japanese role-playing game developed by Squaresoft and designed by Hiroyuki Ito for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Final Fantasy VI was both critically and commercially successful, and had a considerable influence on later steampunk video games.[36]

The Chaos Engine (1993) is a run and gun video game inspired by the Gibson/Sterling novel The Difference Engine (1990), set in a Victorian steampunk age. Developed by the Bitmap Brothers, it was first released on the Amiga in 1993; a sequel was released in 1996.[150] The graphic adventure puzzle video games Myst (1993), Riven (1997), Myst III: Exile (2001), and Myst IV: Revelation (all produced by or under the supervision of Cyan Worlds) take place in an alternate steampunk universe, where elaborate infrastructures have been built to run on steam power. The Elder Scrolls (since 1994, last release in 2014) is an action role-playing game where one can find an ancient extinct race called dwemers or dwarves, whose steampunk technology is based on steam-powered levers and gears made of copper-bronze material, which are maintained by magical techniques that have kept them in working order over the centuries.

Sakura Wars (1996), a visual novel and tactical role-playing game developed by Sega for the Saturn console, is set in a steampunk version of Japan during the Meiji and Taishō periods, and features steam-powered mecha robots.[12] Thief: The Dark Project (1998), its sequels, Thief II (2000), Thief: Deadly Shadows (2004) and its reboot Thief (2014) are set in a steampunk metropolis. The 2001 computer role-playing game Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura mixed fantasy tropes with steampunk.

The Professor Layton series of games (2007 debut) has several entries showcasing steampunk machinery and vehicles. Notably Professor Layton and the Unwound Future features a quasi-steampunk future setting. Solatorobo (2010) is a role-playing video game developed by CyberConnect2 set in a floating island archipelago populated by anthropomorphic cats and dogs, who pilot steampunk airships and engage in combat with robots. Resonance of Fate (2010) is a role-playing video game developed by tri-Ace and published by Sega for the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. It is set in a steampunk environment with combat involving guns.

Impossible Creatures (2003) real-time strategy game inspired by the works of H. G. Welles, especially "The Island of Doctor Moreau". Developed by Relic Entertainment, it sees an adventurer building an army of genetically spliced animals to battle against a mad scientist who has abducted his father. The player's headquarters is a steam-powered "Hovertrain" locomotive, which functions as both a science lab and mobile command center. Coal is a key resource in the game, and must be burned to provide power to the players many base buildings.

The SteamWorld series of games (2010 debut) has the player controlling steam-powered robots. Minecraft (2011) has a steampunk-themed texture pack. Terraria (2011) is a video game developed by Re-Logic. It is a 2D open world platform game in which the player controls a single character in a generated world. It has a Steampunker non-player character in the game who sells items referencing Steampunk. LittleBigPlanet 2 (2011) has the world Victoria's Laboratory, run by Victoria von Bathysphere, which mixes steampunk themes with confections. Guns of Icarus Online (2012) is multiplayer game with steampunk themes.

Dishonored is a series (2012 debut) of stealth games with role-playing elements developed by Arkane Studios and widely considered to be a spiritual successor of the original Thief trilogy. Set in the Empire of the Isles, a steampunk Victorian metropolis where technology and supernatural magic coexist. Steam-powered robots and mechanical combat suits are present as enemies, as well as the presence of magic. The major locations in the Isles include Dunwall, the Empire's capital city which uses the burning of whale oil as the city's main fuel source,[151] and Karnaca, which is powered by wind turbines fed by currents generated by a cleft mountain along the city's borders.[152]

BioShock Infinite (2013) is a first-person shooter game set in 1912, in a fictional city called Columbia, which uses technology to float in the sky and has many historical and religious scenes.[153]

Code: Realize − Guardian of Rebirth (2014), a Japanese otome game for the PS Vita is set in a steampunk Victorian London, and features a cast with several historical figures with steampunk aesthetics. Code Name S.T.E.A.M. (2015), a Japanese tactical RPG game for the 3DS set in a steampunk fantasy version of London where you are a conscript in the strike force S.T.E.A.M. (short for Strike Team Eliminating the Alien Menace). They Are Billions (2017), is a steampunk strategy game in a post-apocalyptic setting. Players build a colony and attempt to ward off waves of zombies. Frostpunk (2018) is a city-building game set in 1888, but where the Earth is in the midst of a great Ice Age. Players must construct a city around a large steampunk heat generator with many steampunk aesthetics and mechanics, such as a "Steam Core."

Culture and community

[edit]

Because of the popularity of steampunk, there is a growing movement of adults that want to establish steampunk as a culture and lifestyle.[154] Some fans of the genre adopt a steampunk aesthetic through fashion,[155] home decor, music, and film. While Steampunk is considered the amalgamation of Victorian aesthetic principles with modern sensibilities and technologies,[23] it can be more broadly categorised as neo-Victorianism, described by scholar Marie-Luise Kohlke as "the afterlife of the nineteenth century in the cultural imaginary".[156] The subculture has its own magazine, blogs, and online shops.[157]

In September 2012, a panel, chaired by steampunk entertainer Veronique Chevalier and with panelists including magician Pop Hadyn and members of the steampunk performance group the League of STEAM, was held at Stan Lee's Comikaze Expo. The panel suggested that because steampunk was inclusive of and incorporated ideas from various other subcultures such as goth, neo-Victorian, and cyberpunk, as well as a growing number of fandoms, it was fast becoming a super-culture rather than a mere subculture.[158] Other steampunk notables such as Professor Elemental have expressed similar views about steampunk's inclusive diversity.[159]

Some have proposed a steampunk philosophy that incorporates punk-inspired anti-establishment sentiments typically bolstered by optimism about human potential.[160] A 2004 "Steampunk Manifesto," later republished in SteamPunk Magazine, lamented that most "so-called" steampunk was nothing more than dressed-up recreationary nostalgia and proposed that "authentic" steampunk would "take the levers of technology from the [technocrats] and powerful."[161] American activist and performer Miriam Rosenberg Rocek impersonated anarcha-feminist Emma Goldman to inspire discussions around gender, society and politics.[4] SteamPunk Magazine was edited and published by anarchists. Its founder, Margaret Killjoy, argued "there have always been radical politics at the core of steampunk."[162] Diana M. Pho, a science-fiction editor and author of the multicultural steampunk blog Beyond Victoriana, similarly argued steampunk's "progressive roots" can be traced to its literary inspirations, including Verne's Captain Nemo.[163] Steampunk authors Phenderson Djèlí Clark,[164] Jaymee Goh,[165] Dru Pagliassotti,[166] and Charlie Stross[167] consider their work political.

These views are not universally shared.[79] Killjoy lamented that even some diehard enthusiasts believe steampunk "has nothing to offer but designer clothes."[162] Pho argued many steampunk fans "don't like to acknowledge that their attitudes could be considered ideological."[163] The largest online steampunk community, Brass Goggles, which is dedicated to what it calls the "lighter side" of steampunk, banned discussion about politics. Cory Gross, who was one of the first to write about the history and theory of steampunk, argued that the "sepia-toned yesteryear more appropriate for Disney and grandparents than a vibrant and viable philosophy or culture" denounced in the Steampunk Manifesto[161] was in fact representative of the genre.[168] Author Catherynne M. Valente called the punk in steampunk "nearly meaningless."[169] Kate Franklin and James Schafer, who at the time managed one of the largest steampunk groups on Facebook, admitted in 2011 that steampunk hadn't created the "revolutionary, or even a particularly progressive" community they wanted.[170] Blogger and podcaster Eric Renderking Fisk announced in 2017 that steampunk was no longer punk, since it had "lost the anti-authoritarian, anti-establishment aspects."[171]

Others argued explicitly against turning steampunk into a political movement,[172] preferring to see steampunk as "escapism"[173] or a "fandom".[174] In 2018, Nick Ottens, editor of the online alternate-history magazine Never Was, declared that the "lighter side" of steampunk had won out.[175] To the extent that steampunk is politicized, it appears to be an American and British phenomenon. Continental Europeans[176] and Latin Americans[177] are more likely to consider steampunk a hobby than a cause.

Social events

[edit]June 19, 2005 marked the grand opening of the world's first steampunk club night, Malediction Society, in Los Angeles.[178][179] The event ran for nearly 12 years at The Monte Cristo nightclub, interrupted by a single year residency at Argyle Hollywood, until both the club night and The Monte Cristo closed in April 2017.[179] Though the steampunk aesthetic eventually gave way to a more generic goth and industrial aesthetic, Malediction Society celebrated its roots every year with "The Steampunk Ball".[180]

The year 2006 saw the first "SalonCon", a neo-Victorian/steampunk convention. It ran for three consecutive years and featured artists, musicians (Voltaire and Abney Park), and authors (Catherynne M. Valente, Ekaterina Sedia, and G. D. Falksen). It also featured salons led by people prominent in their respective fields, workshops and panels on steampunk, and a seance, ballroom dance instruction, and the Chrononauts' Parade. The event was covered by MTV[181] and The New York Times.[23] Since then, a number of popular steampunk conventions have sprung up the world over, with names like Steamcon (Seattle), the Steampunk World's Fair (Piscataway, New Jersey), Up in the Aether: The Steampunk Convention (Dearborn, Michigan),[182] Steampunk NZ (Oamaru, New Zealand), Steampunk Unlimited (Strasburg Railroad, Lancaster, PA).[183] Each year, on Mother's Day weekend, the city of Waltham, MA, turns over its city center and surrounding areas to host the Watch City Steampunk Festival, a US outdoor steampunk festival. In Kennebunk, ME the Brick Store Museum hosts the Southern Maine Steampunk Fair annually.[184][185] During the first weekend of May, the Australian town of Nimmitabel celebrates Steampunk @ Altitude with some 2,000 people in attendance.[186]

In recent years, steampunk has also become a regular feature at San Diego Comic-Con, with the Saturday of the four-day event being generally known among steampunks as "Steampunk Day", and culminating with a photo-shoot for the local press.[187][188] In 2010, this was recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world's largest steampunk photo shoot.[189] In 2013, Comic-Con announced four official 2013 T-shirts, one of them featuring the official Rick Geary Comic-Con toucan mascot in steampunk attire.[190] The Saturday steampunk "after-party" has also become a major event on the steampunk social calendar: in 2010, the headliners included The Slow Poisoner, Unextraordinary Gentlemen, and Aurelio Voltaire, with Veronique Chevalier as Mistress of Ceremonies and special appearance by the League of STEAM;[191][192] in 2011, UXG returned with Abney Park.[193]

Steampunk has also sprung up recently at Renaissance Festivals and Renaissance Faires, in the US. Some festivals have organised events or a "Steampunk Day", while others simply support an open environment for donning steampunk attire. The Bristol Renaissance Faire in Kenosha, Wisconsin, on the Wisconsin/Illinois border, featured a Steampunk costume contest during the 2012 season, the previous two seasons having seen increasing participation in the phenomenon.[194]

Steampunk also has a growing following in the UK and Europe. The largest European event is "Weekend at the Asylum", held at The Lawn, Lincoln, every September since 2009. Organised as a not-for-profit event by the Ministry of Steampunk (formerly Victorian Steampunk Society), the Asylum is a dedicated steampunk event which takes over much of the historical quarter of Lincoln, England, along with Lincoln Castle. In 2011, there were over 1,000 steampunks in attendance. The event features the Empire Ball, Majors Review, Bazaar Eclectica, and the international Tea Duelling final.[195] [196] The Surrey Steampunk Convivial was originally held in New Malden, but since 2019 has been held in Stoneleigh in southwestern London, within walking distance of H. G. Wells's home.[197] The Surrey Steampunk Convivial started as an annual event in 2012, and now takes place thrice a year, and has spanned three boroughs and five venues.[198] Attendees have been interviewed by BBC Radio 4 for Phill Jupitus[199] and filmed by the BBC World Service.[200] The West Yorkshire village of Haworth has held an annual Steampunk weekend since 2013,[201] on each occasion as a charity event raising funds for Sue Ryder's "Manorlands" hospice in Oxenhope. In September 2021, Finland's first steampunk festival was held at the Väinö Linna Square and the Werstas Workers' House in Tampere, Pirkanmaa, Finland.[202][203]

Other

[edit]A 2018 physics Ph.D. dissertation used the phrase "Quantum Steampunk" to describe the author's synthesis of some 19th century and current ideas.[204][205] The term has not been widely adopted.

A 2012 conference paper on human factors in computing systems examined the use of steampunk as a design fiction for human-computer interaction (HCI). It concludes that "the practices of DIY and appropriation that are evident in Steampunk design provide a useful set of design strategies and implications for HCI".[206]

See also

[edit]- Air pirate – Common stock character in steampunk

- Alternate history – Genre of speculative fiction, where one or more historical events occur differently

- Cyberpunk – Science fiction subgenre in a futuristic dystopian setting

- Cyberpunk derivatives – Subgenres of this speculative fiction genre

- Dark academia

- Dieselpunk – Subgenre of science fiction

- Retrofuturism – Creative arts movement inspired by historic depictions of the future

- Retrotronics – The making of electric circuits or appliances using older electric components

- Tik-Tok (Oz) – Fictional character from L. Frank Baum's Oz series

- Technological utopianism

- Afrofuturism

- Solarpunk

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of steampunk". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Latham, Rob (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction. Oxford University Press. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-19-983884-4.

- ^ "What Is Steampunk All About? | Gear Gadgets and Gizmos". www.geargadgetsandgizmos.com/. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved Feb 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Nally, Claire (Nov 7, 2016). "EXPERT COMMENT: Steampunk, Neo-Victorianism, and the Fantastic" (Press release). Northumbria University, Newcastle's Newsroom. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ STEAMPUNK. Lulu.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ Campbell, Heather M. (Dec 1, 2010). "Steampunk: Full Steam Ahead". School Library Journal. 56 (12): 52–57. ISSN 0362-8930. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c VanderMeer, Jeff; Chambers, S. J. (2011). The Steampunk Bible: An Illustrated Guide to the World of Imaginary Airships, Corsets and Goggles, Mad Scientists, and Strange Literature. New York: Abrams Image. ISBN 978-0-8109-8958-0. Archived from the original on 2017-05-22. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- ^ a b c d e Grossman, Lev (December 14, 2009). "Steampunk: Reclaiming Tech for the Masses". Time. Archived from the original on December 9, 2009. Retrieved Dec 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Clute, John; Grant, John; Ashley, Mike; Hartwell, David G.; Westfahl, Gary (1999). The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1st ed.). New York: St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 895–896. ISBN 978-0-312-19869-5.

STEAMPUNK A term applied more to science fiction than to fantasy, though some tales described as steampunk do cross genres. ... Steampunk, on the other hand, can be best described as technofantasy that is based, sometimes quite remotely, upon technological anachronism.

- ^ Taddeo, Julie Anne; Miller, Cynthia J. (2013). Steaming Into a Victorian Future: A Steampunk Anthology. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8108-8586-8.

- ^ "What Is Steampunk – Steam Punk Explained". steam-punk.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Sterling, Bruce (22 March 2013). "Japanese steampunk". Wired. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Steampunk artists meld Victorian era, science fiction". Duluth News Tribune. January 1, 2012. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

It's the stuff Jules Verne used to write about, looking at it from the hindsight of the 21st century,

- ^ "Steampunk's subculture revealed". SFGate. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved Aug 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Strickland, Jonathan (Feb 15, 2008). "Famous Steampunk Works". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Oliveira, Camilla (Nov 2, 2015). "Steampunk: The Movement and the Art". Wall Street International – Culture Section.

- ^ Peake, Mervyn (2011). The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy (New ed.). London: Vintage. p. 753. ISBN 978-0-09-952854-8.

- ^ Daniel, Lucy (2007). Defining Moments In Books: The Greatest Books, Writers, Characters, Passages And Events That Shook The Literary World. New York: Cassell illustrated. p. 439. ISBN 978-1-84403-605-9.

- ^ Bluestocking (21 June 2017). "Steampunk Dollhouse: Islands in the Time Streams or How a Privileged White Edwardian Man Had His Eyes Opened Rather Forcefully". Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Kunzru, Hari (4 February 2011). "When Hari Kunzru Met Michael Moorcock". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bebergal, Peter (August 26, 2007). "The Age of Steampunk". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Kremper, Ella (November 2009). "Beneath an Amber Moon; Brazil" (PDF). Gatehouse Gazette. No. 6. pp. 12–13. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved Jul 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d La Ferla, Ruth (May 8, 2008). "Steampunk Moves Between 2 Worlds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved Nov 21, 2010.

- ^ a b Braiker, Brian (October 31, 2007). "Steampunking Technology: A subculture hand-tools today's gadgets with Victorian style". Newsweek. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010. Retrieved Nov 21, 2010.

- ^ Kaplan, Janet A. (2000). Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys (1st ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0-7892-0627-5.

- ^ a b Duggan, Anne; Haase, Donald; Callow, Helen J. (2016). Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from around the World, 2nd Edition [4 volumes]: Traditions and Texts from around the World. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 835. ISBN 978-1-61069-253-3.

- ^ "What The Hell Is Steampunk?". HuffPost UK. Oct 17, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved Aug 12, 2017.

- ^ Sheidlower, Jesse (March 9, 2005). "Science Fiction Citations". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Jeter, K.W. (April 1987). "Letter – essay from K. W. Jeter". Locus. Vol. 20, no. 4. Locus Publications. Archived from the original on 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

- ^ Nevins, Jess (2003). Heroes & Monsters: The Unofficial Companion to the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Austin, Texas: MonkeyBrain, Inc. ISBN 978-1-932265-04-0.

- ^ Isomaa, Saija; Korpua, Jyrki; Teittinen, Jouni (2020-08-27). New Perspectives on Dystopian Fiction in Literature and Other Media. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-5872-4.

- ^ Lupoff, Richard; Stiles, Steve (February 1980). "The Adventures of Professor Thintwhistle and His Incredible Aether Flyer". Heavy Metal. pp. 27–32 et seq.

- ^ Calamity, Prof. "Steampunk Manifesto". prof-calamity.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved Aug 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Cavallaro, Dani (2015). "Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water (Fushigi no Umi no Nadia)". The Art of Studio Gainax: Experimentation, Style and Innovation at the Leading Edge of Anime. McFarland & Company. pp. 40–53 (40–1). ISBN 978-1-4766-0070-3. Archived from the original on 2023-07-12. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ VanderMeer, Jeff; Chambers, S. J. (2012). The Steampunk Bible: An Illustrated Guide to the World of Imaginary Airships, Corsets and Goggles, Mad Scientists, and Strange Literature. Abrams Books. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-61312-166-5.

- ^ a b Nevins, Jess (2019). "Steampunk". In McFarlane, Anna; Schmeink, Lars; Murphy, Graham (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture. Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-351-13986-1.

- ^ Zion, Lee (May 15, 2001). "Probing the Atlantis Mystery". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Yasuhiro, Takeda (March 25, 2019). "The Notenki Memoirs: Studio Gainax And The Men Who Created Evangelion". Gwern. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Druce, Nikki (2016). Making Steampunk Jewellery. The Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1-78500-215-1.

- ^ Whitson, Roger (2017). Steampunk and Nineteenth-Century Digital Humanities: Literary Retrofuturisms, Media Archaeologies, Alternate Histories. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-317-50911-0.

- ^ Bowser, Rachel A.; Croxall, Brian (2010). "Industrial Evolution" (PDF). Neo-Victorian Studies. 3 (1): 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Guffey, Elizabeth (2014). "Crafting Yesterday's Tomorrows: Retro-Futurism, Steampunk, and the Problem of Making in the Twenty-First Century". The Journal of Modern Craft. 7 (3): 250. doi:10.2752/174967714X14111311182767. S2CID 191495500.

- ^ a b Collazo, Stephanie Amy (December 6, 2011). "YRB Interview: Dr. Grymm". YRB Magazine. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

a dangerous tattoo machine, fusing a tattoo machine and an arm. Using a hand massager, projector parts, tube radios, a paint sprayer and miscellaneous parts (such as a glass vial of squid ink), Marsocci created an interesting piece that looks like something you'd find in Mary Shelley's home.

- ^ a b Casey, Eileen (August 1, 2008). "Steampunk Art And Design Exhibits In The Hamptons". Hamptons Online. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

Steampunk is not considered 'Outsider Art,' but rather a tightly focused art movement whose practitioners faithfully borrow design elements from the grand schools of architecture, science and design and employ a strict philosophy where the physical form must be as equally impressive as the function.

- ^ Catastrophone Orchestra and Arts Collective, "What, Then, is Steampunk? Colonizing the Past So We Can Dream the Future", SteamPunk Magazine 1 (2006), p 4.

- ^ Steel, Sharon (May 19, 2008). "Steam dream: Steampunk bursts through its subculture roots to challenge our musical, fashion, design, and even political sensibilities". The Boston Phoenix. Archived from the original on December 9, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ a b c Hart, Hugh (December 1, 2011). "Steampunk Contraptions Take Over Tattoo Studio". Wired. Archived from the original on December 4, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ Farivar, Cyrus (February 6, 2008). "Steampunk Brings Victorian Flair to the 21st Century". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on January 8, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Jackie (October 17, 2013). "Paris Metro Travel: Full Steam(punk) Ahead at Arts et Métiers". Rail Europe. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014.

- ^ Dodsworth, Lucy (November 7, 2011). "In pictures: Paris' steampunk Arts et Métiers Metro station". On The Luce. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Hartwell, Lane (September 8, 2007). "Best of Burning Man: Fire Dancers, Steampunk Tree House and More". Wired. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

Kinetic Steam Works' Case traction engine Hortense glows on the playa. The art vehicle was named in honor of the artist and mother of Cal Tinkham, the steam enthusiast and railroad engineer who originally restored the engine.

- ^ Savatier, Tristan "Loupiote" (2007). "Kinetic Steam Works' Case traction engine Hortense". Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ^ "Five Ton Crane". Fivetoncrane.org. 2010. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved Aug 6, 2014.

- ^ Jardin, Xeni (24 January 2008). "Steampunk Tree House". Boing Boing TV. Archived from the original on December 9, 2010.

- ^ Orlando, Sean (2007–2008). "Steampunk Tree House". Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ "Steampunk Treehouse Finds Home At Dogfish". Dogfish Head Craft Brewery. 21 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Maker Faire: The Neverwas Haul". Make: DIY Projects, How-Tos, Electronics, Crafts and Ideas for Makers. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved Nov 19, 2015.

- ^ "Crew". Obtainium Works. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved Nov 19, 2015.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (May 21, 2008). "Telescope Takes a Long View, to London". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ Sullivan, Caroline (October 17, 2008). "Tonight I'm gonna party like it's 1899". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ PH, Julie (June 5, 2008). "Testing the Telectroscope". Londonist. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Telectroscope Merged Topic Threads". Brass Goggles. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Wetherell, Tim. "Clockwork Universe". Tim Wetherell. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Taddeo, Julie Anne; Miller, Cynthia J. (2013). Steaming into a Victorian future : a steampunk anthology. Lanham, Md. : Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8586-8. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ^ "Not Remotely Steampunk". Regretsy. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved Aug 26, 2011.

- ^ Pikedevant (Nov 29, 2011). "Just Glue Some Gears On It (And Call It Steampunk)". Youtube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

From the video's comments: 'This is Datamancer, the steampunk keyboard guy, and I approve of this video wholeheartedly. In fact, we make this joke at the workshop almost daily. "I can't figure out how to finish off this edge". "Just glue some gears to it and call it done" haha. Well-made song and video.' – Datamancer. 'Glad to see a new contender for the chap-hop crown, and such a relevant message. I love it!' – Unwoman. 'Professor Elemental here, Just wanted to give this my most hearty applause. A fine, fine song by a true gentleman.'

- ^ "The Steampunk movement in Oxford". BBC News. Oct 26, 2009. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved Apr 12, 2016.

- ^ "Steampunk". Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. Archived from the original on 2009-08-31. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

Imagine the technology of today with the aesthetic of Victorian science.

- ^ Ward, Mark (November 30, 2009). "Tech Know: Fast forward to the past". BBC News. Archived from the original on December 3, 2009. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ "Lonely Planet launches latest New Zealand guide (2012, Steampunk HQ one of author's top 12 recommendations)". New Zealand Government official tourism website. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved Mar 21, 2014.

- ^ "Oamaru - steampunk capital of the world Archived 2022-01-11 at the Wayback Machine", Radio New Zealand, 1 November 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Roy, E. A., "How an ordinary New Zealand town became steampunk capital of the world Archived 2022-01-11 at the Wayback Machine", The Guardian, 30 August 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "ModVic | Steampunk Museum Art & Residential and Commercial DesignModvic". Jun 20, 2015. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved Apr 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Stiffler, Scott (January 19, 2012). "Steampunk: The Victorian future is now". the Villager. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ "Mobilis in Mobili Art Exhibit Gives Steampunks Some New Ink to Spill". Tor.com. Dec 2, 2011. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved Aug 6, 2014.

- ^ "Exhibitor: The Oxford Artisan Distillery". Whisky Show. London: The Whisky Exchange. October 2021. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Jean (2009). Steampunk Style Jewelry: A Maker's Collection of Victorian, Fantasy, and Mechanical Designs. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Creative Publishing International. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-58923-475-8.

- ^ "Steampunk Sunglasses – All you need to know!". The Urban Crew. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved Jul 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c Damon Poeter (July 6, 2008). "Steampunk's subculture revealed". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Rowe, Andrew Ross (September 29, 2008). "What Is Steampunk? A Subculture Infiltrating Films, Music, Fashion, More". MTV. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ^ "Company Spotlight: Steampunk Couture". Steampunk Journal. Feb 20, 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved Apr 11, 2014.

- ^ Dahncke, Pasha Ray. "IBM Social Sentiment Index Predicts New Retail Trend in the Making" (Press release). IBM. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ a b Skarda, Erin (Jan 17, 2013). "Will Steampunk Really Be the Next Big Fashion Trend?". Time. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved Feb 18, 2013.

- ^ Stubby the Rocket (June 25, 2012). "Sci-Fi Actors Wearing Steampunk Clothes Designed by Prada". Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved Mar 28, 2014.

- ^ Cicatrix13 (Mar 6, 2013). "Steampunk Couture Hot on the Runway (and We're Not Talking Airships)". Steampunk Workshop. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Under the Gunn, Episode 7: "Steampunk Chic"". Threads Magazine. Mar 6, 2014. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ "America's Next Top Model goes STEAMPUNK". LacedAndWaisted. September 30, 2012. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "Heliograph's Space 1889 Resource Site". Heliograph, Inc. Jun 30, 2010. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved Nov 29, 2010.

- ^ Csicsery-Ronay, Istvan (March 1997). "Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr. | The Critic". Science Fiction Studies (#71, Volume 24, Part 1). DePauw University, Greencastle Indiana: SF-TH Inc. Archived from the original on March 20, 2009. Retrieved Nov 29, 2010.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory (July 8, 2007). "Jay Lake's "Mainspring:" Clockpunk adventure". Archived from the original on April 22, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Liddo, Annalisa Di (2010-01-06). Alan Moore: Comics as Performance, Fiction as Scalpel. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-476-8.

- ^ Gosling, Sharon (February 28, 2013). "Sharon Gosling's top 10 children's steampunk books". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ Czyrnyj, Alasdair (November 2009). "Adventures at Armageddon; Review; Leviathan" (PDF). Gatehouse Gazette. No. 9. pp. 10–11. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved Jul 28, 2020.

- ^ Carpenter, Susan (2012-09-23). "Not Just For Kids: 'The Peculiar' by Stefan Bachmann is a fantastical tale". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2022-10-27. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ^ Corbett, Sue (Sep 28, 2012). "What's New in YA? Mashups". PublishersWeekly.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved Apr 12, 2016.

- ^ "Meet the Victorian Steampunk Society". SFX News. November 27, 2011. Archived from the original on December 1, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ Misra, Ria (May 19, 2014). "That Time Hellboy Got "Steampunk" Added To The Dictionary". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved Jul 28, 2020.

- ^ Morehead, John W. (2015-05-23). The Supernatural Cinema of Guillermo del Toro: Critical Essays. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2075-6.

- ^ Barger, Andrew (2013). Mesaerion: The Best Science Fiction Short Stories 1800–1849. Bottletree Books Llc. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-933747-49-1.

- ^ "Skies of Arcadia review on RPGnet". RPG.net. Archived from the original on March 23, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ "Rise of legends as steampunk video game". Dailygame.net. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ Xerin (March 9, 2010). "WoW: Loremaster's Corner #5: A Steampunk Paradise". Ten Ton Hammer. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

World of Warcraft is almost a steampunk paradise if you look at the various technological advancements the gnomes have made. Most engines are powered by steam and there are giant airships floating around everywhere.

- ^ "Lore:Dwemer Animunculi – The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages". UESP. Apr 24, 2017. Archived from the original on November 28, 2016. Retrieved Jun 5, 2017.

- ^ a b "Unprecedented level of game service operation' from Steampunk MMORPG Neo Steam". June 29, 2008. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Davia, Lorenzo (January 2011). "Magico Vento" (PDF). Gatehouse Gazette. No. 16. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved Jul 28, 2020.

- ^ Kinkade, Scott (August 10, 2013). "Dead Iron – Book Review". Gatehouse Gazette. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved Jul 28, 2020.

- ^ Richardson-Brown, James (2008). "Steampunk – What's That All About". The Chronicles. Vol. 2, no. 9. p. 10.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (August 18, 2009). "9 Review". Variety. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ Latham, Rob; Guffey, Elizabeth; Lemay, Kate C. (Nov 1, 2014). "Retrofuturism and Steampunk". The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199838844.013.0034. ISBN 978-0-19-983884-4. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ "The Clockwork of Progress: The Victorian Era Unwound". Infinite Steampunk. 2024-02-15. Retrieved 2024-08-13.

- ^ Hudson, Patrick. "(Review of) The Difference Engine". The Zone. Pigasus Press. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ School Library Journal,Laviathan. Simon Pulse. Oct 6, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4169-7173-3. Retrieved Aug 19, 2011.

- ^ Bertschy, Zac (July 21, 2004). "Steamboy". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ Waldrop, Howard; Person, Lawrence (October 13, 2004). "The Fabulous World of Jules Verne". Locus Online. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ "The news and media magazine of the British Science Fiction Association". Matrix Online. June 30, 2008. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ Ward, Cynthia (August 20, 2003). "Hayao Miyazaki: The Greatest Fantasy Director You Never Heard Of?". Locus Online. Archived from the original on August 7, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2009.