Transylvanian Saxon dialect

| Transylvanian Saxon | |

|---|---|

| Siweberjesch-Såksesch/Såksesch | |

| |

| Native to | |

| Region | |

Native speakers | 200,000[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | tran1294 |

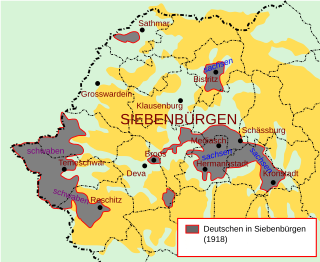

Areas where Transylvanian Saxon was spoken in the Kingdom of Romania in 1918 (the grey-coloured areas to the west denote where Swabian was spoken). | |

Transylvanian Saxon is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Transylvanian Saxon is the native German dialect of the Transylvanian Saxons, an ethnic German minority group from Transylvania in central Romania, and is also one of the three oldest ethnic German and German-speaking groups of the German diaspora in Central and Eastern Europe, along with the Baltic Germans and Zipser Germans.[2][3] In addition, the Transylvanian Saxons are the eldest ethnic German group of all constituent others forming the broader community of the Germans of Romania.

The dialect is known by the endonym Siweberjesch Såksesch or just Såksesch; in German as Siebenbürgisch-Sächsisch, Siebenbürgisch-sächsischer Dialekt/Mundart, or Die siebenbürgisch-sächsische Sprache (obsolete German spelling: Siebenbürgisch Teutsch); in Transylvanian Landler dialect as Soksisch; in Hungarian as erdélyi szász nyelv; and in Romanian as Limba săsească, săsește, or dialectul săsesc.

Linguistically, the Transylvanian Saxon dialect is very close to Luxembourgish (especially regarding its vocabulary). This is because many ancestors of the present-day Transylvanian Saxons stemmed from contemporary Luxembourg as early as the 12th century, especially in the area of contemporary Sibiu County (German: Kreis Hermannstadt), as part of the Ostsiedlung process. In their case, the Ostsiedlung colonisation process took place in southern, southeastern, and northeastern Transylvania for economic development, guarding the easternmost borders of the former Kingdom of Hungary as well as mining, especially in the area of Bistrița (German: Bistritz or Nösen, archaic form).[4]

Consequently, the Transylvanian Saxon dialect has been spoken in the south, southeast, and northeast of Transylvania since the High Middle Ages onwards.[5][6] In addition, the Transylvanian Saxon dialect is also similar to the Zipser German dialect spoken by the Zipsers in Spiš (German: Zips), northeastern Slovakia as well as Maramureș (i.e. Maramureș County) and Bukovina (i.e. Suceava County), northeastern Romania.[7]

There are two main types or varieties of the dialect, more specifically northern Transylvanian Saxon (German: Nordsiebenbürgisch), spoken in Nösnerland (Romanian: Țara Năsăudului) including the dialect of Bistrița, and south Transylvanian Saxon (German: Südsiebenbürgisch), including, most notably, the dialect of Sibiu (German: Hermannstadt). In the process of its development, the Transylvanian Saxon dialect has been influenced by Romanian and Hungarian as well.[8] Nowadays, given its relatively small number of native speakers worldwide, the dialect is severely endangered.

Background

[edit]

In terms of comparative linguistics, it pertains to the Moselle Franconian group of West Central German dialects. In this particular regard, it must be mentioned that it shares a consistent amount of lexical similarities with Luxembourgish.[9][10]

The dialect was mainly spoken in Transylvania (contemporary central Romania), by native speakers of German, Flemish, and Walloon origins who were settled in the Kingdom of Hungary starting in the mid and mid-late 12th century (more specifically from approximately the 1140s/1150s to the 19th century). Over the passing of time, it had been consistently influenced by both Romanian and Hungarian given the centuries-long cohabitation of the Saxons with Romanians and Hungarians (mostly Szeklers) in the south, southeast, and northeast of Transylvania.[11][12][13] The main areas where Transylvanian Saxon was spoken in Transylvania were southern and northern Transylvania.[14][15]

In the contemporary era, the vast majority of the native speakers have emigrated in several waves, initially to Germany and Austria, but then subsequently to the US, Canada as well as other Western European countries, managing in the process to preserve (at least temporarily) their specific language there.

Lastly, one can perceive the Transylvanian Saxon dialect, bearing in mind its conservative character when compared to other dialects of the German language (due primarily to its geographic isolation from other German idioms) as a type of German spoken in medieval times, or, more specifically as Old High German or Middle High German.

Geographic distribution of the dialect in Transylvania

[edit]Traditionally, the Transylvanian Saxon dialect was mainly spoken in the rural areas of Transylvania throughout the passing of time, since the arrival of the Transylvanian Saxons in the Carpathian Basin during the Middle Ages (more specifically beginning in the 12th century) onwards. In the urban settlements (i.e. several towns and cities such as Sibiu/Hermannstadt or Brașov/Kronstadt), standard German (i.e. Hochdeutsch) was more spoken and written more instead.

The traditional areas where the Transylvanian Saxon dialect has been spoken are southern Transylvania and north-eastern Transylvania which represent the main areas of settlement of the Transylvanian Saxons since the High Middle Ages onwards. These areas correspond mainly to Sibiu County, Brașov County, Mureș County, and Bistrița-Năsăud County and, to a lesser extent, Alba County and Hunedoara County respectively.

Furthermore, the Transylvanian Saxon dialect also varied from village to village where it was spoken (that is, a village could have had a slightly different local form of Transylvanian Saxon than the other but there was still a certain degree of mutual intelligibility between them; for instance, more or less analogous and similar to how English accents vary on a radius of 5 miles (8.0 km) in the England/United Kingdom).

Recent history of the dialect (1989–present)

[edit]Before the Romanian Revolution of 1989, most of the Transylvanian Saxons were still living in Transylvania. During the communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu, many thousands of these Saxons were sold for a total sum of money of around $6 million paid to communist Romania by West Germany.[16]

By 1990, the number of Saxons living in Transylvania had decreased dramatically. Shortly after the fall of communism, from 1991 to 1994, many Transylvanian Saxons who still remained in Transylvania decided to ultimately emigrate to re-unified Germany, leaving just a minority of approximately 20,000 Transylvanian Saxons in Romania at the round of the 21st century (or less than 1 percent of the entire population of Transylvania).[17][18]

The number of native Transylvanian Saxon speakers today is estimated at approximately 200,000 persons. Transylvanian Saxon is also the native dialect of the current President of Romania, Klaus Iohannis, by virtue of the fact that he is a Transylvanian Saxon.[19] It is also the native dialect of well known German rock superstar Peter Maffay. Additionally, according to the 2011 Romanian census, only 11,400 Transylvanian Saxon were still living in Transylvania at that time.[20] The 2021 Romanian census (postponed one year to 2022 because of the COVID-19 pandemic in Romania) reported a smaller overall figure for the German minority in Romania and, most probably, an even fewer number of native Transylvanian Saxon speakers still living in Transylvania.

Sample text

[edit]Below is a sample text written in the Transylvanian Saxon dialect, entitled 'De Råch' (meaning 'The Revenge'), which is, more specifically, an old traditional ballad/poem (also translated and in comparison with standard German/Hochdeutsch and English):[21]

| De Råch (Transylvanian Saxon in original) Hië ritt berjuëf, hië ritt berjåff, |

Die Rache (Standard German)[b] Er ritt bergab, er ritt bergauf, |

The Revenge (English translation) He rode downhill, he rode uphill, |

Below is another sample text of religious nature, more specifically the Our Father prayer:[22]

| Foater auser (Transylvanian Saxon in original) Foater auser dier dau best em Hemmel, |

Alphabet

[edit]- A – a

- B – be

- C – ce

- D – de

- E – e

- F – ef

- G – ge

- H – ha

- I – i

- J – jot

- K – ka

- L – el

- M – em

- N – en

- O – o

- P – pe

- Q – ku

- R – er

- S – es

- T – te

- U – u

- V – vau

- W – we

- X – ix

- Y – ipsilon

- Z – zet[23]

Orthography and pronunciation

[edit]Vowels

[edit]- a – [a/aː]

- au – [aʊ̯]

- å – [ɔː]

- ä – [ɛ/ɛː]

- äi – [eɪ̯]

- e – [ɛ~e~ə/eː]

- ei – [aɪ̯]

- ë – [e]

- i – [ɪ/iː]

- ië – [i]

- o – [ɔ/oː]

- u – [ʊ/uː]

- uë – [u]

- ü/y – [ʏ/yː][24]

Consonants

[edit]- b – [b~p]

- c – [k~ɡ̊]

- ch – [x~ʃ]

- ck – [k]

- d – [d~t]

- dsch – [d͡ʒ]

- f – [f]

- g – [ɡ~k~ʃ]

- h – [h~ː]

- j – [j]

- k – [k~ɡ̊]

- l – [l]

- m – [m]

- n – [n]

- ng – [ŋ]

- nj – [ɲ]

- p – [p~b̥]

- pf – [p͡f]

- qv – [kv]

- r – [r~∅]

- s – [s~ʃ~z]

- sch – [ʃ]

- ss – [s]

- t – [t~d̥]

- tsch – [t͡ʃ]

- v – [f/v]

- w – [v]

- x – [ks]

- z – [t͡s][25]

Bibliography

[edit]- Siebenbürgisch-Sächsisches Wörterbuch. A. Schullerus, B. Capesius, A. Tudt, S. Haldenwang et al. (in German)

- Band 1, Buchstabe A – C, 1925, de Gruyter, ASIN: B0000BUORT

- Band 2, Buchstabe D – F, 1926, de Gruyter, ASIN: B0000BUORU

- Band 3, Buchstabe G, 1971, de Gruyter, ASIN: B0000BUORV

- Band 4, Buchstabe H – J, 1972

- Band 5, Buchstabe K, 1975

- Band 6, Buchstabe L, 1997, Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 978-3-412-03286-9

- Band 7: Buchstabe M, 1998, Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 978-3-412-09098-2

- Band 8, Buchstabe N – P, 2002, Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 978-3-412-12801-2

- Band 9: Buchstabe Q – R, 2007, Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 978-3-412-06906-3

- Band 10: Buchstabe S – Sche, 2014, Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 978-3-412-22410-3

- Band 11: Schentzel – Schnapp-, 2020, Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 978-3412519810

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also spoken in Germany, Austria, several Western European countries, and in North America, more specifically in the United States and Canada.

- ^ Originally translated from Transylvanian Saxon to standard German by German Wikipedia user DietG.

- ^ Bäsch should mean forest or Wald in standard German, but, so as for the rhyme to still remain, Busch or bush was written here instead.

References

[edit]- ^ "Transylvanian Saxon (Siweberjesch Såksesch)". Omniglot. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Victor Rouă (19 August 2015). "A Brief History Of The Transylvanian Saxon Dialect". The Dockyards. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Adelheid Frățilă, Hildegard-Anna Falk (January 2011). "Das siebenbürgisch-sächsische eine inselmundart im vergleich mit dem Hochdeutschen" (PDF). Neue Didaktik (in German). Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Vu(m) Nathalie Lodhi (13 January 2020). "The Transylvanian Saxon dialect, a not-so-distant cousin of Luxembourgish". RTL Luxembourg. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Ariana Bancu (March 2020). "Transylvanian Saxon dialectal areas". RsearchGate. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Ariana Bancu. "The Transylvanian Saxon language islands around 1913 (Source: Klein 1961, map number 3)" (in German). Research Gate. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Helmut Protze (2006). "Die Zipser Sachsen im sprachgeographischen und sprachhistorischen Vergleich zu den Siebenbürger Sachsen". Central and Eastern European Online Library (in German). Arbeitskreis für Siebenbürgische Landeskunde. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Sigrid Haldenwang. "Zur Entlehnung rumänischer Verben ins Siebenbürgisch-Sächsische aufgrund von Fallbeispielen" (PDF). Academic article (in German). Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Vu(m) Nathalie Lodhi (13 January 2020). "The Transylvanian Saxon dialect, a not-so-distant cousin of Luxembourgish". RTL. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Stephen McGrath (10 September 2019). "The Saxons first arrived in Romania's Transylvania region in the 12th Century, but over the past few decades the community has all but vanished from the region". BBC Travel. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Bernhard Capesius. Wesen und Werden des Siebenbürgisch-Sächsischen, vol.8/1, 1965, p. 19 and 22 to 25 (in German).

- ^ "Dictionary of Transylvanian Saxon Dialects". Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities Sibiu. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Gisela Richter (1960). "Zur Bereicherung der siebenbürgisch-sächsischen Mundart durch die rumänische Sprache/On the Enrichment of the Transylvanian-Saxon Dialect by the Romanian Language". Forschungen zur Volks- und Landeskunde (in German) (3). Editura Academiei Române: 37–56. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Bancu, Ariana. (2020). Two case studies on structural variation in multilingual settings. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America. 5. 750. 10.3765/plsa.v5i1.4760.

- ^ Ariana Bancu (March 2020). "Transylvanian Saxon dialectal areas". Two case studies on structural variation in multilingual settings. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Popescu, Karin (12 October 1996). "Vast Corruption Revealed In Ceausescu Visa Scheme". Moscow Times. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Transylvanian Saxons". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Nationalia (17 November 2014). "Saxon, Lutheran President for Romania: Klaus Iohannis and the "job well done"". Nationalia. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Robert Schwartz (20 October 2015). "Breathing new life into Transylvania's crumbling cultural sites". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Table no. 8". Recensământ România (in Romanian). Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Michael Markel (1973). Es sang ein klein Waldvögelein. Siebenbürgische Volkslieder, sächsisch und deutsch. Editura Dacia in Cluj-Napoca/Klausenburg.

- ^ "Siebenbürgisch-Sächsisch Rosary Prayers". Mary's Rosaries. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Transylvanian Saxon". Omniglot. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Transylvanian Saxon language". Omniglot. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Transylvanian Saxon language". Omniglot. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

External links

[edit]- Transylvanian Saxon Resource Hub at the University of Konstanz (in English and German)

- SibiWeb: Die Sprache des siebenbürgisch-sächsischen Volkes von Adolf Schullerus (German)

- Verband der Siebenbürgersachsen in Deutschland: Sprachaufnahmen in siebenbürgisch-sächsischer Mundart – Audiosamples (German, Såksesch)

- Siebenbürgersachsen Baden-Württemberg: Die Mundart der Siebenbürger Sachsen von Waltraut Schuller (German)

- Hörprobe in Siebenbürgersächsisch (Mundart von Honigberg – Hărman) und Vergleich mit anderen Germanischen Sprachen (German)