Chennai

Chennai

Ceṉṉai (Tamil) Madras | |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise from top: Chennai Central railway station; Valluvar Kottam; Kathipara junction; Marina beach; Ripon Building; the Triumph of Labour and Kapaleeswarar Temple | |

| Nicknames: | |

| |

| Coordinates: 13°4′57″N 80°16′30″E / 13.08250°N 80.27500°E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Tamil Nadu |

| District | Chennai[a] |

| Established | 1639 |

| Named for | [b] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Body | Greater Chennai Corporation |

| • Mayor | Priya Rajan |

| • Commissioner | J. Kumaragurubaran IAS |

| Area | |

• Megacity | 426 km2 (164 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 5,904 km2 (2,280 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Population | |

• Megacity | 6,748,026 |

| • Rank | 6th |

| • Density | 16,000/km2 (41,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 8,696,010 |

| • Metro rank | 4th |

| Demonym | Chennaiite |

| GDP (2022-23) | |

| • Megacity[c] | $143.9 billion[8][9] |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| Pincode(s) | 600xxx |

| Area code | +91-44 |

| Vehicle registration | TN-01 to TN-14, TN-18, TN-22, TN-85 |

| Official languages | Tamil, English |

| Website | chennaicorporation |

| Population Note: The population as per 2011 census calculated basis pre-expansion city area of 174 sq.km. was 4,646,732.[7] Post expansion of city limits to 426 sq.km.,[4] the population including the new city limits was provided by Government of Tamil Nadu was 6,748,026.[10] The 2011 census data for the urban agglomeration is available and has been provided.[7] | |

Chennai (/ˈtʃɛnaɪ/ ⓘ; Tamil: [ˈt͡ɕenːaɪ̯], ISO: Ceṉṉai), formerly known as Madras,[d] is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian census, Chennai is the sixth-most populous city in India and forms the fourth-most populous urban agglomeration. Incorporated in 1688, the Greater Chennai Corporation is the oldest municipal corporation in India and the second oldest in the world after London.

Historically, the region was part of the Chola, Pandya, Pallava and Vijayanagara kingdoms during various eras. The coastal land which then contained the fishing village Madrasapattinam, was purchased by the British East India Company from the Nayak ruler Chennapa Nayaka in the 17th century. The British garrison established the Madras city and port and built Fort St. George, the first British fortress in India. The city was made the winter capital of the Madras Presidency, a colonial province of the British Raj in the Indian subcontinent. After India gained independence in 1947, Madras continued as the capital city of the Madras State and present-day Tamil Nadu. The city was officially renamed as Chennai in 1996.

The city is coterminous with Chennai district, which together with the adjoining suburbs constitutes the Chennai Metropolitan Area,[e] the 35th-largest urban area in the world by population and one of the largest metropolitan economies of India. Chennai has the fifth-largest urban economy and the third-largest expatriate population in India. Known as the gateway to South India, Chennai is amongst the most-visited Indian cities by international tourists and was ranked 36th among the most-visited cities in the world in 2019 by Euromonitor. Ranked as a beta-level city in the Global Cities Index, it was ranked as the second most safest city in India by National Crime Records Bureau in 2023.

Chennai is a major centre for medical tourism and is termed "India's health capital". Chennai houses a major portion of India's automobile industry, hence the name "Detroit of India". It was the only South Asian city to be ranked among National Geographic's "Top 10 food cities" in 2015 and ranked ninth on Lonely Planet's best cosmopolitan cities in the world. In October 2017, Chennai was added to the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN) list. It is a major film production centre and home to the Tamil-language film industry.

Etymology

The name Chennai was derived from the name of Chennappa Nayaka, a Nayak ruler who served as a general under Venkata Raya of the Vijayanagara Empire from whom the British East India Company acquired the town in 1639.[12][13] The first official use of the name was in August 1639 in a sale deed to Francis Day of the East India Company.[14] A land grant was given to the Chennakesava Perumal Temple in Chennapatanam later in 1646, which some scholars argue to be the first use of the name.[15][12]

The name Madras is of native origin, and has been shown to have been in use before the British established a presence in India.[16] A Vijayanagara-era inscription found in 2015 was dated to the year 1367 and mentions the port of Mādarasanpattanam, along with other small ports on the east coast, and it was theorized that the aforementioned port is the fishing port of Royapuram.[17] Madras might have been derived from Madraspattinam, a fishing village north of Fort St. George but it is uncertain whether the name was in use before the arrival of Europeans.[18]

In July 1996, the Government of Tamil Nadu officially changed the name from Madras to Chennai.[19] The name "Madras" continues to be used occasionally for the city as well as for places or things named after the city in the past.[20]

History

Stone Age implements have been found near Pallavaram in Chennai and according to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), Pallavaram was a megalithic cultural establishment, and pre-historic communities resided in the settlement.[21] The region around Chennai was an important administrative, military, and economic centre for many centuries. During the 1st century CE, Tamil poet named Thiruvalluvar lived in the town of Mylapore, a neighbourhood of present-day Chennai.[22] The region was part of Tondaimandalam which was ruled by the Early Cholas in the 2nd century CE by subduing Kurumbas, the original inhabitants of the region.[23] Pallavas of Kanchi became independent rulers of the region from 3rd to 9th century CE and the areas of Mahabalipuram and Pallavaram were built during the reign of Mahendravarman I.[24] In 879, Pallavas were defeated by the Later Cholas led by Aditya I and Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan later brought the region under the Pandya rule in 1264.[23] The region came under the influence of Vijayanagara Empire in the 15th century CE.[25][23]

The Portuguese arrived in 1522 and built a port named São Tomé after the Christian apostle, St. Thomas, who is believed to have preached in the area between 52 and 70 CE. In 1612, the Dutch established themselves near Pulicat, north of Chennai.[26] On 20 August 1639, Francis Day of the British East India Company along with the Nayak of Kalahasti Chennappa Nayaka met with the Vijayanager Emperor Peda Venkata Raya at Chandragiri and obtained a grant for land on the Coromandel coast on which the company could build a factory and warehouse for their trading activities.[27] On 22 August, he secured the grant for a strip of land about 9.7 km (6 mi) long and 1.6 km (1 mi) inland in return for a yearly sum of five hundred lakh pagodas.[28][29] The region was then formerly a fishing village known as "Madraspatnam".[26] A year later, the company built Fort St. George, the first major English settlement in India, which became the nucleus of the growing colonial city and urban Chennai.[30][31]

In 1746, Fort St. George and the town were captured by the French under General La Bourdonnais, the Governor of Mauritius, who plundered the town and its outlying villages.[26] The British regained control in 1749 through the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and strengthened the town's fortress wall to withstand further attacks from the French and Hyder Ali, the king of Mysore.[32] They resisted a French siege attempt in 1759.[33] In 1769, the city was threatened by Hyder Ali during the First Anglo-Mysore War with the Treaty of Madras ending the conflict.[34] By the 18th century, the British had conquered most of the region and established the Madras Presidency with Madras as the capital.[35]

The city became a major naval base and became the central administrative centre for the British in South India.[36] The city was the baseline for the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, which was started on 10 April 1802.[37] With the advent of railways in India in the 19th century, the city was connected to other major cities such as Bombay and Calcutta, promoting increased communication and trade with the hinterland.[38]

After India gained its independence in 1947, the city became the capital of Madras State, the predecessor of the current state of Tamil Nadu.[39] The city was the location of the hunger strike and death of Potti Sreeramulu which resulted in the formation of Andhra State in 1953 and eventually the re-organization of Indian states based on linguistic boundaries in 1956.[40][41]

In 1965, agitations against the imposition of Hindi and in support of continuing English as a medium of communication arose which marked a major shift in the political dynamics of the city and eventually led to English being retained as an official language of India alongside Hindi.[42][43] On 17 July 1996, the city was officially renamed from Madras to Chennai, in line with then a nationwide trend to using less Anglicised names.[44] On 26 December 2004, a tsunami lashed the shores of Chennai, killing 206 people in Chennai and permanently altering the coastline.[45] The 2015 Chennai Floods submerged major portions of the city, killing 269 people and resulting in damages of ₹86.4 billion (US$1 billion).[46]

Environment

Geography

Chennai is located on the southeastern coast of India in the northeastern part of Tamil Nadu on a flat coastal plain known as the Eastern Coastal Plains with an average elevation of 6.7 m (22 ft) and highest point at 60 m (200 ft).[47][48] Chennai's soil is mostly clay, shale and sandstone.[49] Clay underlies most of the city with sandy areas found along the river banks and coasts where rainwater runoff percolates quickly through the soil. Certain areas in South Chennai have a hard rock surface.[50][51] As of 2018, the city had a green cover of 14.9 per cent, with a per capita green cover of 8.5 square metres against the World Health Organization recommendation of nine square metres.[52]

As of 2017[update], water bodies cover an estimated 3.2 km2 (1.2 sq mi) area of the city.[53] Two major rivers flow through Chennai, the Cooum River (or Koovam) through the centre and the Adyar River to the south.[54] A section of the Buckingham Canal built in 1877-78, runs parallel to the Bay of Bengal coast, linking the two rivers.[55] Kosasthalaiyar River traverses through the northern fringes of the city before draining into the Bay of Bengal, at Ennore Creek.[56] The Otteri Nullah, an east–west stream, runs through north Chennai and meets the Buckingham Canal at Basin Bridge.[57] The groundwater table in Chennai is at 4–5 m (13–16 ft) below ground level on average and is replenished mainly by rainwater.[58] Of the 24.87 km (15.45 mi) coastline of the city, 3.08 km (1.91 mi) experiences erosion, with sand accretion along the shoreline at the Marina beach and the area between the Ennore Port and Kosasthalaiyar river.[59]

Geology

Chennai is situated in Seismic Zone III, indicating a moderate risk of damage from earthquakes.[60] Owing to the tectonic zone the city falls in, the city is considered a potential geothermal energy site. The crust has old granite rocks dating back nearly a billion years indicating volcanic activities in the past with expected temperatures of 200–300 °C (392–572 °F) at 4–5 km (2.5–3.1 mi) depth.[61]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Chennai has the dry-summer version of a tropical savanna climate (As),[62][63] closely bordering the dry-winter version (Aw) due to a February average rainfall of 4.7 mm (0.19 in). The city lies on the thermal equator and as it is also located on the coast, there is no extreme variation in seasonal temperature.[64] The hottest time of the year is from April to June with an average temperature of 35–40 °C (95–104 °F).[65] The highest recorded temperature was 45 °C (113 °F) on 31 May 2003.[66] The coldest time of the year is in December–January, with average temperature of 19–25 °C (66–77 °F) and the lowest recorded temperature of 13.9 °C (57.0 °F) on 11 December 1895 and 29 January 1905.[67]

Chennai receives most of its rainfall from the northeast monsoon between October and December while smaller amounts of rain come from the southwest monsoon between June and September. The average annual rainfall is about 120 cm (47 in).[68] The highest annual rainfall recorded was 257 cm (101 in) in 2005.[69] Prevailing winds in Chennai are usually southwesterly between April and October and northeasterly during the rest of the year.[70] The city relies on the annual monsoon rains to replenish water reservoirs.[71] Cyclones and depressions are common features during the season.[72] Water inundation and flooding happen in low-lying areas during the season with significant flooding in 2015 and 2023.[73]

| Climate data for Chennai (Nungambakkam; rainfall from Chennai Airport) 1991–2020, extremes 1901–2012 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.4 (93.9) |

36.7 (98.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

42.8 (109.0) |

45.0 (113.0) |

43.3 (109.9) |

41.1 (106.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

39.4 (102.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

45.0 (113.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.3 (84.7) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

37.1 (98.8) |

37.0 (98.6) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

28.9 (84.0) |

33.1 (91.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.4 (77.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

28.5 (83.3) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 20.0 (0.79) |

4.7 (0.19) |

3.4 (0.13) |

17.5 (0.69) |

49.7 (1.96) |

75.4 (2.97) |

113.1 (4.45) |

141.4 (5.57) |

143.9 (5.67) |

278.3 (10.96) |

377.3 (14.85) |

183.7 (7.23) |

1,408.4 (55.45) |

| Average rainy days | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 5.7 | 60.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 67 | 66 | 67 | 70 | 68 | 63 | 65 | 66 | 71 | 76 | 76 | 71 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 232.5 | 240.1 | 291.4 | 294.0 | 300.7 | 234.0 | 142.6 | 189.1 | 195.0 | 257.3 | 261.0 | 210.8 | 2,848.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.5 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 7.8 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 6.8 | 7.8 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department[74][75][76][77] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Tokyo Climate Center (mean temperatures 1991–2020)[78] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

A protected estuary on the Adyar River forms a natural habitat for several species of birds and animals.[79] Chennai is also a popular city for birding with more than 130 recorded species of birds have been recorded in the city.[80] Marshy wetlands such as Pallikaranai and inland lakes also host a number of migratory birds during the monsoon and winter.[81][82] The southern stretch of Chennai's coast from Tiruvanmiyur to Neelangarai are favoured by the endangered olive ridley sea turtles to lay eggs every winter.[83] Guindy National Park is a protected area within the city limits and wildlife conservation and research activities take place at Arignar Anna Zoological Park.[84] Madras Crocodile Bank Trust is a herpetology research station, located 40 km (25 mi) south of Chennai.[85][86] The city's tree cover is estimated to be around 64.06 km2 (24.73 sq mi) with 121 recorded species belonging to 94 genera and 42 families. Major species include Copper pod, Indian beech, Gulmohar, Raintree, Neem, and Tropical Almond.[87] The city's marine and inland water bodies house a number of fresh water and salt water fishes, and marine organisms.[88][89]

Environmental issues

Chennai had many lakes spread across the city, but urbanization has led to the shrinkage of water bodies and wetlands.[90][91] The water bodies have shrunk from an estimated 12.6 km2 (4.9 sq mi) in 1893 to 3.2 km2 (1.2 sq mi) in 2017.[53] The number of wetlands in the city has decreased from 650 in 1970 to 27 in 2015.[92] Nearly half of the native plant species in the city's wetlands have disappeared with only 25 per cent of the erstwhile area covered with aquatic plants still viable.[93] The major water bodies including the Adyar, Cooum and Kosathaliyar rivers, and the Buckingham canal are heavily polluted with effluents and waste from domestic and commercial sources.[94][95][54] The encroachment of urban development on wetlands has hampered the sustainability of water bodies and was a major contributor to the floods in 2015 and 2023 and water scarcity crisis in 2019.[96][97]

The Chennai River Restoration Trust set up by the government of Tamil Nadu is working on the restoration of the Adyar River.[98] The Environmentalist Foundation of India is a volunteering group working towards wildlife conservation and habitat restoration.[99][100]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1639 | 7,000 | — |

| 1646 | 19,000 | +171.4% |

| 1670 | 40,000 | +110.5% |

| 1681 | 200,000 | +400.0% |

| 1685 | 300,000 | +50.0% |

| 1691 | 400,000 | +33.3% |

| 1715 | 100,000 | −75.0% |

| 1726 | 100,000 | +0.0% |

| 1733 | 100,000 | +0.0% |

| 1791 | 300,000 | +200.0% |

| 1871 | 367,552 | +22.5% |

| 1881 | 405,848 | +10.4% |

| 1891 | 452,518 | +11.5% |

| 1901 | 509,346 | +12.6% |

| 1911 | 518,660 | +1.8% |

| 1921 | 526,911 | +1.6% |

| 1931 | 647,232 | +22.8% |

| 1941 | 777,481 | +20.1% |

| 1951 | 1,416,056 | +82.1% |

| 1961 | 1,729,141 | +22.1% |

| 1971 | 2,469,449 | +42.8% |

| 1981 | 3,266,034 | +32.3% |

| 1991 | 3,841,396 | +17.6% |

| 2001 | 4,343,645 | +13.1% |

| 2011 | 6,748,026 | +55.4% |

| Source: | ||

A resident of Chennai is called a Chennaite.[108][109] According to 2011 census, the city had a population of 4,646,732, within an area of 174 km2 (67 sq mi).[110] Post expansion of the city to 426 km2 (164 sq mi), the Chennai Municipal Corporation was renamed as Greater Chennai Corporation and the population including the new city limits as per the 2011 census was 6,748,026.[10][4][111] As of 2019[update], 40 per cent of the 1.788 million families in the city live below the poverty line.[112] As of 2017[update], the city had 2.2 million households, with 40 per cent of the residents not owning a house.[113] There are about 1,131 slums in the city housing more than 300,000 households.[114]

Administration and politics

Administration

The city is governed by the Greater Chennai Corporation (formerly "Corporation of Madras"), which was established on 29 September 1688. It is the oldest surviving municipal corporation in India and the second oldest surviving corporation in the world.[115] In 2011, the jurisdiction of the Chennai Corporation was expanded from 174 km2 (67 sq mi) to an area of 426 km2 (164 sq mi), divided into three regions North, South and Central covering 200 wards.[116][117] The corporation is headed by a mayor, elected by the councillors, who are elected through a popular vote by the residents.[118][119]

The Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) is the nodal agency responsible for the planning and development of the Chennai Metropolitan Area, which is spread over an area of 1,189 km2 (459 sq mi), covering the Chennai district and parts of Tiruvallur, Kanchipuram and Chengalpattu districts.[120] The metropolitan area consists of four municipal corporations, 12 municipalities and other smaller panchayats.[5][121]

As the capital of the state of Tamil Nadu, the city houses the state executive and legislative headquarters primarily in the secretariat buildings in Fort St George.[122] Madras High Court is the highest judicial authority in the state, whose jurisdiction extends across Tamil Nadu and Puducherry.[123]

Law and order

The Greater Chennai Police (GCP) is the primary law enforcement agency in the city and is headed by a commissioner of police.[124] The Greater Chennai Police is a division of the Tamil Nadu Police, the administrative control of which lies with the Home ministry of the Government of Tamil Nadu.[125][126] Greater Chennai Traffic Police (GCTP) is responsible for the traffic management in the city.[127] The metropolitan suburbs are policed by the Chennai Metropolitan Police, headed by the Chennai Police Commissionerate, and the outer district areas of the CMDA are policed by respective police departments of Tiruvallur, Kanchipuram, Chengalpattu and Ranipet districts.[128]

As of 2021[update], Greater Chennai had 135 police stations across four zones with 20,000 police personnel.[129][130] As of 2021[update], the crime rate in the city was 101.2 per hundred thousand people.[131] It was ranked as the second most safest city in India by National Crime Records Bureau in 2023.[132] In 2009, Madras Central Prison, the major prison and one of the oldest in India was demolished with the prisoners moved to the newly constructed Puzhal Central Prison.[133]

Politics

While the major part of the city falls under three parliamentary constituencies (Chennai North, Chennai Central and Chennai South), the Chennai metropolitan area is spread across five constituencies. It elects 28 MLAs to the state legislature.[134][135] Being the capital of the Madras Province that covered a large area of the Deccan region, Chennai remained the centre of politics during the British colonial era. Chennai is the birthplace of the idea of the Indian National Congress, which was founded by the members of the Theosophical Society movement based on the idea conceived in a private meeting after a Theosophical convention held in the city in December 1884.[136][137] The city has hosted yearly conferences of the Congress seven times, playing a major part in the Indian independence movement.[138] Chennai is also the birthplace of regional political parties such as the South Indian Welfare Association in 1916 which later became the Justice Party and Dravidar Kazhagam.[139][140]

Politics is characterized by a mix of regional and national political parties.[141] During the 1920s and 1930s, the Self-Respect Movement, spearheaded by Theagaroya Chetty and E. V. Ramaswamy emerged in Madras.[142] Congress dominated the political scene post Independence in the 1950s and 1960s under C. Rajagopalachari and later K. Kamaraj.[143] The Anti-Hindi agitations led to the rise of Dravidian parties with Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) forming the first government under C. N. Annadurai in 1967. In 1972, a split in the DMK resulted in the formation of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) led by M. G. Ramachandran. The two Dravidian parties continue to dominate electoral politics, the national parties usually aligning as junior partners to the two major Dravidian parties.[144][145] Many film personalities became politicians and later chief ministers, including C. N. Annadurai, M. Karunanidhi, M. G. Ramachandran, Janaki Ramachandran and Jayalalithaa.[146]

Culture

Languages

Tamil is the language spoken by most of Chennai's population; English is largely spoken by white-collar workers.[147][148] As per the 2011 census, Tamil is the most spoken language with 3,640,389 (78.3%) of speakers followed by Telugu (432,295), Urdu (198,505), Hindi (159,474) and Malayalam (104,994).[149] Madras Bashai is a variety of the Tamil spoken by people in the city.[150] It originated with words introduced from other languages such as English and Telugu on the Tamil originally spoken by the native people of the city.[151] Korean,[152] Japanese,[153] French,[154] Mandarin Chinese,[155] German[156] and Spanish are spoken by foreign expatriates residing in the city.[154]

Religion and ethnicity

Chennai is home to a diverse population of ethno-religious communities.[158][159] As per census of 2011, Chennai's population was majority Hindu (80.73%) with 9.45% Muslim, 7.72% Christian, 1.27% others and 0.83% with no religion or not indicating any religious preference.[157] Tamils form majority of the population with minorities including Telugus,[160] Marwaris,[161] Gujaratis,[162] Parsis,[163] Sindhis,[164] Odias,[165] Goans,[166] Kannadigas,[167] Anglo-Indians,[168] Bengalis,[169] Punjabis,[170] and Malayalees.[171] The city also has a significant expatriate population.[172][173] As of 2001[update], out of the 2,937,000 migrants in the city, 61.5% were from other parts of the state, 33.8% were from rest of India and 3.7% were from outside the country.[174]

Architecture

With the history of Chennai dating back centuries, the architecture of Chennai ranges in a wide chronology. The oldest buildings in the city date from the 6th to 8th centuries CE, which include the Kapaleeshwarar Temple in Mylapore and the Parthasarathy Temple in Triplicane, built in the Dravidian architecture encompassing various styles developed during the reigns of different empires.[175] In Dravidian architecture, the Hindu temples consisted of large mantapas with gate-pyramids called gopurams in quadrangular enclosures that surround the temple.[176][177] The Gopuram, a monumental tower usually ornate at the entrance of the temple forms a prominent feature of Koils and whose origins can be traced back to the Pallavas who built the group of monuments in Mamallapuram.[178][179] The associated Agraharam architecture, which consists of traditional row houses can still be seen in the areas surrounding the temples.[180] Chennai has the second highest number of heritage buildings in the country.[181]

With the Mugals influence in mediaeval times and the British later, the city saw a rise in a blend of Hindu, Islamic and Gothic revival styles, resulting in the distinct Indo-Saracenic architecture.[182] The architecture for several institutions followed the Indo-Saracenic style with the Chepauk Palace designed by Paul Benfield amongst the first Indo-Saracenic buildings in India.[183] Other buildings in the city from the era designed in this style of architecture include Fort St. George (1640), Amir Mahal (1798), Government Museum (1854), Senate House of the University of Madras (1879), Victoria Public Hall (1886), Madras High Court (1892), Bharat Insurance Building (1897), Ripon Building (1913), College of Engineering (1920) and Southern Railway headquarters (1921).[184]

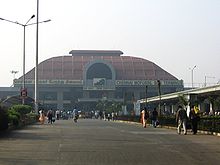

Gothic revival-style buildings include the Chennai Central and Chennai Egmore railway stations. The Santhome Church, which was originally built by the Portuguese in 1523 and is believed to house the remains of the apostle St. Thomas, was rebuilt in 1893, in neo-Gothic style.[185] By the early 20th century, the art deco made its entry upon the city's urban landscape with buildings in George Town including the United India building (presently housing LIC) and the Burma Shell building (presently the Chennai House), both built in the 1930s, and the Dare House built in 1940 examples of this architecture.[186] After Independence, the city witnessed a rise in the Modernism and the completion of the LIC Building in 1959, the tallest building in the country at that time marked the transition from lime-and-brick construction to concrete columns.[187]

The presence of the weather radar at the Chennai Port prohibited the construction of buildings taller than 60 m around a radius of 10 km till 2009.[188][187] This resulted in the central business district expanding horizontally, unlike other metropolitan cities, while the peripheral regions began experiencing vertical growth with the construction of taller buildings with the tallest building at 161 metres (528 ft).[189]

Arts

Chennai is a major centre for music, art and dance in India.[190] The city is called the Cultural Capital of South India.[191] Madras Music Season, initiated by Madras Music Academy in 1927, is celebrated every year during the month of December and features performances of traditional Carnatic music by artists from the city.[192] Madras University introduced a course of music, as part of the Bachelor of Arts curriculum in 1930.[193] Gaana, a combination of various folk music, is sung mainly in the working-class area of North Chennai.[194] Chennai Sangamam, an art festival showcasing various arts of South India is held every year.[195] Chennai has been featured in UNESCO Creative Cities Network list since October 2017 for its old musical tradition.[196]

Chennai has a diverse theatre scene and is a prominent centre for Bharata Natyam, a classical dance form that originated in Tamil Nadu and is the oldest dance in India.[197] Cultural centres in the city include Kalakshetra and Government Music College.[198] Chennai is also home to some choirs, who during the Christmas season stage various carol performances across the city in Tamil and English.[199]

Chennai is home to many museums, galleries, and other institutions that engage in arts research and are major tourist attractions.[200] Established in the early 18th century, the Government Museum and the National Art Gallery are amongst the oldest in the country.[201] The museum inside the premises of Fort St. George maintains a collection of objects of the British era.[202] The museum is managed by the Archaeological Survey of India and has in its possession, the first Flag of India hoisted at Fort St George after the declaration of India's Independence on 15 August 1947.[203]

Chennai is the base for Tamil cinema, nicknamed Kollywood, alluding to the neighbourhood of Kodambakkam where several film studios are located.[204] The history of cinema in South India started in 1897 when a European exhibitor first screened a selection of silent short films at the Victoria Public Hall in the city.[205] Swamikannu Vincent purchased a film projector and erected tents for screening films which became popular in the early 20th century.[206] Keechaka Vadham, the first film in South India was produced in the city and released in 1917.[207] Gemini and Vijaya Vauhini studios were established in the 1940s, amongst the largest and earliest in the country.[208] Chennai hosts many major film studios, including AVM Productions, the oldest surviving studio in India.[209]

Cuisine

Chennai cuisine is predominantly South Indian with rice as its base. Most local restaurants still retain their rural flavour, with many restaurants serving food over a banana leaf.[210] Eating on a banana leaf is an old custom and imparts a unique flavour to the food and is considered healthy.[211] Idly and dosa are popular breakfast dishes.[212][213] Chennai has an active street food culture and various cuisine options for dining including North Indian, Chinese and continental.[214][215] The influx of industries in the early 21st century also bought distinct cuisines from other countries such as Japanese and Korean to the city.[216] Chennai was the only South Asian city to be ranked among National Geographic's "Top 10 food cities" in 2015.[217]

Economy

The economy of Chennai consistently exceeded national average growth rates due to reform-oriented economic policies in the 1970s.[218] With the presence of two major ports, an international airport, and a converging road and rail networks, Chennai is often referred to as the "Gateway to South India".[1][219] According to the Globalization and World Cities Research Network, Chennai is amongst the most integrated with the global economy, classified as a beta-city.[220] As of 31 March 2023[update], Chennai had an estimated GDP of $143.9 billion ranking it among the most productive metro areas in India.[8][9] Chennai has a diversified industrial base anchored by different sectors including automobiles, software services, hardware, healthcare and financial services.[221][222] As of 2021[update], Chennai is amongst the top export districts in the country with more than US$2563 billion in exports.[223]

The city has a permanent exhibition complex Chennai Trade Centre at Nandambakkam.[224] The city hosts the Tamil Nadu Global Investors Meet, a business summit organized by the Government of Tamil Nadu.[225] With about 62% of the population classified as affluent with less than 1% asset-poor, Chennai has the fifth highest number of millionaires.[226][227][228]

Chennai is among the major information technology (IT) hubs of India.[229] Tidel Park established in 2000 was amongst the first and largest IT parks in Asia.[230] The presence of SEZs and government policies have contributed to the growth of the sector which has attracted foreign investments and job seekers from other parts of the country.[231][232] In the 2020s, the city has become a major provider of SaaS and has been dubbed the "SaaS Capital of India".[233][234]

The automotive industry in Chennai accounts for more than 35% of India's overall automotive components and automobile output, earning the nickname "Detroit of India".[235][236] A large number of automotive companies have their manufacturing bases in the city.[237] Integral Coach Factory in Chennai manufactures railway coaches and other rolling stock for Indian Railways.[238] Ambattur Industrial Estate housing various manufacturing units is among the largest small-scale industrial estates in the country.[239] Chennai contributes more than 50 per cent of India's leather exports.[240] Chennai is a major electronics hardware exporter.[241]

The city is home to the Madras Stock Exchange, India's third-largest by trading volume behind the Bombay Stock Exchange and the National Stock Exchange of India.[242][243] Madras Bank, the first European-style banking system in India, was established on 21 June 1683 followed by first commercial banks such as Bank of Hindustan (1770) and General Bank of India (1786).[244] Bank of Madras merged with two other presidency banks to form Imperial Bank of India in 1921 which in 1955 became the State Bank of India, the largest bank in India.[245] Chennai is the headquarters of nationalized banks Indian Bank and Indian Overseas Bank.[246][247] Chennai hosts the south zonal office of the Reserve Bank of India, the country's central bank, along with its zonal training centre and staff College, one of the two colleges run by the bank.[248] The city also houses a permanent back office of the World Bank.[249] About 400 financial industry businesses are headquartered in the city.[250][251]

DRDO, India's premier defence research agency operates various facilities in Chennai.[252] Heavy Vehicles Factory of the AVANI, headquartered in Chennai manufactures Armoured fighting vehicles, Main battle tanks, tank engines and armoured clothing for the use of the Indian Armed Forces.[253][254] ISRO, the premier Indian space agency primarily responsible for performing tasks related to space exploration operates research facilities in the city.[255] As per Euromonitor, Chennai is the fourth-most visited city in India by international tourists and 36th internationally in 2019.[256][257] Medical tourism forms an important part of the city's economy with more than 40% of total medical tourists visiting India making it to Chennai.[258]

Infrastructure

Water supply

The city's water supply and sewage treatment are managed by the Chennai MetroWater Supply and Sewage Board. Water is drawn from Red Hills Lake and Chembarambakkam Lake, the major water reservoirs in the city and treated at water treatment plants located at Kilpauk, Puzhal, Chembarambakkam and supplied to the city through 27 water distribution stations.[259][260] The city receives 530 million litres per day (mld) of water from Krishna River through Telugu Ganga project and 180 mld of water from the Veeranam lake project.[261] 100 million litres of treated water per day is produced from the Minjur desalination plant, the country's largest seawater desalination plant.[262] Chennai is predicted to face a deficit of 713 mld of water by 2026 as the demand is projected at 2,248 mld and supply estimated at 1,535 mld.[263] The city's sewer system was designed in 1910, with some modifications in 1958.[264]

Waste management

Chennai generates 4,500 tonnes of garbage every day, of which 429 tonnes are plastic waste.[265] The Greater Chennai Corporation undertakes garbage collection and processing with collection in some of the wards contracted to private companies.[266][267] As of 2023[update], an average of 150 tonnes of garbage disposal is done in two landfill sites at Kodungaiyur and Pallikaranai daily.[268][269] In market and business areas, the conservancy work is done during the night.[270] As of 2022[update], there are public toilets in 943 locations, managed by the city corporation.[271]

Communication

Chennai is one of four Indian cities connected by undersea fibre-optic cables and is the landing point of SMW4 (connecting with Europe, Middle East and Southeast Asia), i2i and TIC (connecting with Singapore), BBG (connecting with Middle East, Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka), Gulf Bridge International (connecting with Middle East), and BRICS (connecting with Brazil, Russia, China and South Africa) with 3,175 kilometres (1,973 mi) long i2i having the world's largest design capacity of 8.4 terabits per second.[272][273][274] As of 2023[update], four mobile phone service companies operate GSM networks including Bharti Airtel, BSNL, Vodafone Idea and Reliance Jio offering 4G and 5G mobile services.[275][276] Wireline and broadband services are offered by five major operators and other smaller local operators.[276] Chennai is amongst the cities with a high internet usage and penetration.[277] As of 2022[update], the city had the highest average broadband speed among Indian cities, with a recorded download speed of 32.67 Mbit/s.[278]

Power

Electricity distribution is done by the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board headquartered in Chennai.[279] As of 2023[update], the city consumes an average of 2,750 MW of power daily, which is above 18% of the total power consumption of 15,000 MW by the state of Tamil Nadu and ranks the second highest among all cities nationally.[280] The city has over 248,000 streetlights maintained by the corporation.[281] Major fossil fuel power plants in the city include North Chennai Thermal Power Station, GMR Vasavi Diesel Power Plant, Ennore Thermal Power Station, Basin Bridge Gas Turbine Power Station, Madras Atomic Power Station and Vallur Thermal Power Project.[282] Madras Atomic Power Station located at Kalpakkam about 80 km (50 mi) south of the city is a comprehensive nuclear power production, fuel reprocessing, and waste treatment facility and is the first fully indigenous nuclear power station in India.[283]

Health care

Chennai has a well-developed health infrastructure, including both government-run and private hospitals. The corporation runs 138 primary health centres, 14 secondary health centres, three maternity hospitals and three veterinary health centres.[284] The corporation also runs six diagnostic centres, 37 shelters and 10 health centres for the homeless.[284] The city attracts many health tourists from abroad and other states and has been termed as India's health capital.[3] Major government run hospitals include Government General Hospital, Government multi-super specialty hospital, Kilpauk medical college hospital, Government Royapettah Hospital, Stanley medical college hospital, Government hospital of thoracic medicine, Adyar Cancer Institute, TB Sanatorium and National Institute of Siddha.[285][286] The Government General Hospital was started by 16 November 1664 and was the first major hospital in India.[287] Major private hospitals in the city include Apollo Hospitals, Billroth Hospitals, Dr. Mehta's Hospital, Fortis Malar Hospital, Madras Medical Mission, MIOT Hospitals, Sankara Nethralaya, SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Research Institute, Global Hospitals, Chettinad Hospitals, Kauvery Hospital and Vijaya Hospitals.[285] Corporation is responsible for administration of polio vaccine for eligible age groups.[288] King Institute of Preventive Medicine and Research established in 1899 is a research institute specializing in preventive medicine and vaccination.[289]

Media

Newspaper publishing started in Chennai with the launch of the weekly The Madras Courier in 1785.[290] It was followed by the weeklies The Madras Gazette and The Government Gazette in 1795.[291][292] The Spectator, founded in 1836 was the first English newspaper in Chennai to be owned by an Indian and became the city's first daily newspaper in 1853.[293] The first Telugu journal printed from Madras was Satya Doota in 1835, and the first Tamil newspaper, Swadesamitran, was launched in 1899.[294][295] Chennai has several newspapers and magazines published in various languages including Tamil, English and Telugu.[296] The major dailies with a circulation of more than 100,000 copies per day include The Hindu, Dina Thanthi, Dinakaran, The Times of India, Dina Malar and The Deccan Chronicle.[297] Several periodicals and local newspapers prevalent in select localities also bring out editions from the city.[298]

The government run Doordarshan broadcasts terrestrial and satellite television channels from its Chennai centre set up in 1974.[299] Many private satellite television networks including Sun Network, one of India's largest broadcasting companies, are based in the city.[300] The cable TV service is entirely controlled by the state government while DTH and IPTV is available via various private operators.[301][302] Radio broadcasting began in 1924 by the Madras Presidency Radio Club.[303] All India Radio was established in 1938.[304] The city has four AM and 11 FM radio stations operated by All India Radio, Hello FM, Suryan FM, Radio Mirchi, Radio City and BIG FM among others.[305][306]

Others

Fire services are handled by the Tamil Nadu Fire and Rescue Services, which operates 33 operating fire stations.[307] The corporation also owns 52 community halls across the city.[308] Postal services are handled by India Post, which operates 568 post offices, of which nearly 460 operate from rented premises.[309] The first post office was established on 1 June 1786 at Fort St. George on 1 June 1786.[310]

Transport

Air

The aviation history of Chennai began in 1910, when Giacomo D'Angelis built the first powered flight in Asia and tested it in Island Grounds.[311] In 1915, Tata Air Mail started an airmail service between Karachi and Madras marking the beginning of civil aviation in India.[312] In March 1930, a discussion initiated by pilot G. Vlasto led to the founding of Madras Flying Club.[313][314] On 15 October 1932, J. R. D. Tata flew a Puss Moth aircraft carrying air mail from Karachi to Bombay's Juhu Airstrip and the flight was continued to Madras piloted by aviator Nevill Vintcent marking the first scheduled commercial flight.[315][316] The city is served by Chennai International Airport located in Tirusulam, around 20 kilometres (12 mi) southwest of the city centre.[317] It is the fourth-busiest airport in India in terms of passenger traffic and cargo handled.[318] While the existing airport is undergoing expansion with an addition of 1,069.99 acres (433.01 ha), a new greenfield airport has been proposed to handle additional traffic.[319]

The region comes under the purview of the Southern Air Command of the Indian Air Force. The Air Force operates an air base at Tambaram.[320] The Indian Navy operates airbases at Arakkonam and Chennai.[321][322]

Rail

The history of railway in Chennai began in 1832, when the first railway line in India was proposed between Little Mount and Chintadripet in the city which became operational in 1837.[323] The Madras Railway was established later in 1845 and the construction on the first main line between Madras and Arcot started in 1853, which became operational in 1856.[324] In 1944, all the railway companies operating in British India were taken over by the Government.[325] In December 1950, the Central Advisory Committee for Railways approved the plan for Indian Railways into six zonal systems and the Southern Railway zone was created on 14 April 1951 by merging three state railways, namely, the Madras and Southern Mahratta Railway, the South Indian Railway Company, and the Mysore State Railway with Chennai as the headquarters.[326] The city has four major railway terminals at Chennai Central, Egmore, Beach and Tambaram.[327] Chennai Central, city's largest station provides access to other major stations nationally and is amongst the busiest stations in the country.[328]

- Suburban and MRTS

Chennai has a well-established suburban railway network operated by Southern railway, which was established in 1928.[329] The Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) is an elevated urban mass transit system established in 1995 operating on a single line from Chennai Beach to Velachery.[329]

| System | Lines | Stations | Length | Opened |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chennai Suburban[330] | 3 | 53 | 212 km (132 mi) | 1928 |

| Chennai MRTS[331] | 1 | 17 | 19.715 km (12.250 mi) | 1995 |

- Metro

Chennai Metro is a rapid transit rail system in Chennai that was opened in 2015. As of 2023, the metro system consists of two operational lines operating across 54.1 km (33.6 mi) with 41 stations.[332] The Chennai metro system is being expanded with a proposed addition of three more lines and an extension of 116.1 km (72.1 mi).[333]

| Line | Terminal | Opened | Length (km) |

Stations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Line | Wimco Nagar | Chennai Airport | 21 September 2016 | 32.65 | 26 |

| Green Line | Chennai Central | St. Thomas Mount | 29 June 2015 | 22 | 17 |

| Total | 54.65 | 41 | |||

Road

Chennai has an extensive road network covering about 1,780 km (1,110 mi) as of 2023.[334][335] Chennai is one of the termini of the Golden Quadrilateral system of National Highways connecting it to Mumbai and Kolkata.[336] In addition, two other major national highways namely, NH 45 and NH 205 originate from the city while it is connected to other major towns of the state and Puducherry by state highways.[337] The city has grade separators and flyovers at major intersections, and two peripheral roads (inner and outer ring roads).[338] There are two expressways under construction: Chennai Port–Maduravoyal Expressway and Bangalore–Chennai Expressway.[339][340]

As of 2021[update], there are over six million registered vehicles in the city.[341] Public bus transport is handled by the Metropolitan Transport Corporation of Tamil Nadu State Transport Corporation, which is run by the Government of Tamil Nadu. It was established in 1947 when private buses operating in Madras presidency were nationalized by the government and runs about 3233 buses As of 2023[update].[342] State Express Transport Corporation Limited (SETC), established in 1980, runs long-distance express services exceeding 250 km and above and links the city with other important cities and adjoining states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and the Union Territory of Puducherry. SETC operates various classes of services such as semi-deluxe, ultra-deluxe and air-conditioned with advance booking and reservation on all of its routes.[343] Chennai Mofussil Bus Terminus is one of the largest bus stations in Asia and caters to outstation buses.[344] The other means of road transport in the city include vans, auto rickshaws, on-call metered taxis and tourist taxis.[345]

Water

Chennai has two major ports Chennai and Ennore which are managed by the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways of the Government of India.[346] There are three minor ports, which are managed by the department of highways and minor ports of Government of Tamil Nadu.[334][347] Royapuram fishing harbour is used by fishing boats.[348] Indian Navy has a major base at Chennai.[349][350]

Education

Chennai is a major educational hub and home to some of the premium educational institutions in the country.[351] The city has a 90.33% literacy rate and ranks second among the major Indian metropolitan city centres.[352] Chennai has a mix of public and private schools with the public school system managed by the school education department of Government of Tamil Nadu. As of 2023[update], there are 420 public schools run by Greater Chennai Corporation.[353] Public schools run by the Chennai Corporation are all affiliated with the Tamil Nadu State Board, while private schools may be affiliated with either of Tamil Nadu Board of Secondary Education, Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (ICSE) or National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS).[354] School education starts with two years of Kindergarten from age three onwards and then follows the Indian 10+2 plan, ten years of school and two years of higher secondary education.[355]

The University of Madras was founded in 1857 and is one of India's first modern universities.[356] Colleges for science, arts, and commerce degrees are typically affiliated with the University of Madras, which has six campuses in the city.[357] Indian Institute of Technology Madras is a premier institute of engineering and College of Engineering, Guindy, Anna University founded in 1794 is the oldest engineering college in India.[358]

Officers Training Academy of the Indian Army is headquartered in the city.[359] There are eight government-run medical colleges in the city including one dental college, three for traditional medicine and four for modern medicine apart from multiple private colleges operating under the purview of Tamil Nadu Dr. M.G.R. Medical University in Chennai.[360] Madras Medical College was established in 1835 and is one of the oldest medical colleges in India.[361]

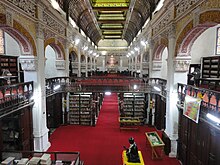

Chennai has many libraries with the major ones being the Connemara Public Library (estd. 1896), one of the four National Depository Centres in India that receive a copy of all newspapers and books published in the country and the Anna Centenary Library, the largest library in Asia.[362][363][364] Chennai has two CSIR research institutions namely Central Leather Research Institute and Structural Engineering Research Centre.[365] Chennai book fair is an annual book fair organized by the Booksellers and Publishers Association of South India (BAPASI) and is typically held in December–January.[366]

Tourism and recreation

With temples, beaches and centres of historical and cultural significance including the UNESCO Heritage Site of Mahabalipuram, Chennai is one of the most-visited cities in India with 11 million domestic and 630,000 foreign tourists visiting in 2020.[367] The gateway to the southern part of India,[368] Chennai was ranked among the top hundred destinations by Euromonitor.[369][370] As of 2018[update], the city has about 7,000 luxury rooms across four- and five-star categories, with 85 per cent of the room demand coming from business travellers.[371][372] Chennai has a 19 km (12 mi) coastline with many beaches including the Marina spanning 13 km (8.1 mi) which is the second-longest urban beach in the world and Elliot's Beach south of the Adyar delta.[373][374]

As of 2023[update], Chennai has 835 public parks maintained by the corporation.[375] The largest park is the 358-acre Tholkappia Poonga, developed to restore the fragile ecosystem of the Adyar estuary.[376] Semmoli Poonga is a 20 acres (8.1 ha) botanical garden maintained by the horticulture department.[377] Madras Crocodile Bank is a reptile zoo located 40 km (25 mi) south of the city and has one of the largest collections of reptiles in the country.[378] Arignar Anna zoological park is a large urban zoo with more than two million visitors annually.[379] Guindy National Park is a protected area within the city limits and has a children's park and a snake park associated with it.[380] Chennai also houses several theme parks and amusement parks.[381]

As of 2012[update], there are 120 cinema screens and multiplexes.[382] Stage plays and dramas of different genres and languages are enacted in theatres across the city.[383] Chennai is also home to several malls.[384] The city is an important market for jewellery.[385] Anna Nagar and Nungambakkam are amongst the expensive retail zones in the country.[386]

Sports

Cricket is the most popular sport in Chennai and was introduced in 1864 with the foundation of the Madras Cricket Club.[387] The M.A. Chidambaram Stadium, established in 1916, is one of the oldest cricket stadiums in India and has hosted matches during multiple ICC Cricket World Cups.[388] Other cricketing venues include Chemplast Cricket Ground and Guru Nanak College Ground.[389][390] Prominent cricketers from the city include S. Venkataraghavan,[391] Kris Srikkanth,[392] and Ravichandran Ashwin.[393] Established in 1987, MRF Pace Foundation is a bowling academy based in Chennai.[394] Chennai is home to the most successful Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket team Chennai Super Kings and hosted the finals during the 2011, 2012, and 2024 seasons.[395][396]

Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium is a multi-purpose venue which hosts football and athletics and also houses a multi–purpose indoor complex for volleyball, basketball, kabaddi and table tennis.[397] Chennai hosted the 1995 South Asian Games.[398] Football club Chennaiyin FC competes in Indian Super League (ISL), the top tier association football league of India and uses the Nehru Stadium for their home matches.[399] Mayor Radhakrishnan Stadium is associated with hockey and was venue for the international hockey tournament the 2005 Men's Champions Trophy and the 2007 Men's Asia Cup.[400] Water sports are played in the Velachery Aquatic Complex.[401] Chennai was the host of the only ATP World Tour event in India, the Chennai Open held at SDAT Tennis Stadium from 1997 to 2017.[402] Vijay Amritraj, Mahesh Bhupathi Ramesh Krishnan and Somdev Devvarman were professional tennis players from Chennai.[403] Chennai is home to Chennai Slam, two-time national champion of India's top professional basketball division, the UBA Pro Basketball League.[404]

Madras Boat Club (founded in 1846) and Royal Madras Yacht Club (founded in 1911) promote sailing, rowing and canoeing sports in Chennai.[405] Inaugurated in 1990, Madras Motor Race Track was the first permanent racing circuit in India and hosts formula racing events.[406] Formula One driver Karun Chandhok was from the city.[407] Horse racing is held at the Guindy Race Course and the city has two 18-hole golf courses, the Cosmopolitan Club and the Gymkhana Club established in the late nineteenth century.[408] Chennai is often dubbed "India's chess capital" as the city is home to multiple chess grandmasters including former world champion Viswanathan Anand.[409][410] The city played host to the World Chess Championship 2013 and 44th Chess Olympiad in 2022.[411][412] Other sports persons from Chennai include table tennis player Sharath Kamal and two–time world carrom champion, Maria Irudayam.[413][414]

City based teams

International relations

Foreign missions

The consular presence in the city dates back to 1794, when William Abbott was appointed US consular agent for South India.[422][423] As of 2022[update], there are 60 foreign representations in Chennai, including 16 consulates general and 28 honorary consulates.[424][425] American Consulate in Chennai is amongst the top employment-based visa processing centres.[426] The Foreigners Regional Registration Office (FRRO) is in charge of immigration and registration activities in the city.[427]

Sister cities

Chennai has sister city relationships with the following cities of the world:

| City | Country | State/Region | Since | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volgograd | Volgograd Oblast | 1966 | [428] | |

| Denver | Colorado | 1984 | [428] | |

| San Antonio | Texas | 2008 | [429] | |

| Kuala Lumpur | Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur | 2010 | [430] | |

| Chongqing | Municipality of Chongqing | 2015 | [431] | |

| Ulsan | Ulsan Metropolitan City | 2016 | [432] |

Notable people

See also

Notes

- ^ a b The Chennai Metropolitan Area also includes portions of Kanchipuram, Chengalpattu, Tiruvallur districts adjoining the Chennai District

- ^ There is a disagreement among scholars as to the origin of the first use of the name.

- ^ The GDP numbers are projected numbers at current prices and correspond to the pre-expansion city limits.

- ^ /məˈdrɑːs/ ⓘ or /-ˈdræs/[11]

- ^ The term Chennai is often used to denote the Chennai Metropolitan Area, colloquially applied for the wider area than just the city. This area includes the city/district of Chennai, and adjacent parts from its three neighbouring districts. This wider usage of the term has been documented as far back as 1639, when the Madras Municipal Corporation was created

References

- ^ a b Sharma, Reetu (23 August 2014). "Chennai turns 375: Things you should know about 'Gateway to South India'". One India. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Business America. U.S. Department of Commerce. 1997. p. 14. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b Hamid, Zubeda (20 August 2012). "The medical capital's place in history". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ a b c "Chennai city just got bigger". The Times of India. 30 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b "CMDA, about us". CMDA. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Cities having population 1 Lakh and above (PDF) (Report). The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Census 2011: Population of cities in India (Report). The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Chennai - C40 Cities". C40 Group. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ a b District Income estimates (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "About Chennai district". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Roach, Peter; Hartmann, James; Setter, Jane (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ a b "History | Chennai District | India". 9 December 2023. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023.

- ^ Srinivasachari, C S (1939). History of the City of Madrae third-largest economys. P Varadachary and co. pp. 63–69. Retrieved 27 November 2023 – via Government of Tamil Nadu.

- ^ Muthiah, S. (4 March 2012). "The 'Town Temple' resurrected". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012.

- ^ S. Muthiah (2008). Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India. Palaniappa Brothers. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Krishnamachari, Suganthy (21 August 2014). "Madras is not alien". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021.

- ^ Krishnamachari, Suganthy (21 August 2014). "Madras is not alien". The Hindu. No. Friday Review. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2011. ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Madras' 384th anniversary: The making of Madras". The New Indian Express. 22 August 2023. Archived from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Madras nalla Madras!". The Hindu. 9 April 2012. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Road workers stumble upon ancient grinding stone in Pallavaram". The Times of India. 19 September 2010. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Awakening Indians to India. Central Chinmaya Mission Trust. 2008. p. 215. ISBN 978-8-17597-433-3.

- ^ a b c "Chennai, history". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain; Hurry, Kenneth (2003). A brief history of India. Alain Daniélou. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-59477-794-3. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Chola, Vijayanagara period copper coins found on riverbed". The Times of India. 9 October 2023. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ a b c "Origin of the Name Madras". Greater Chennai Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Rao, Velcheru Narayana; Shulman, David; Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1998). Symbols of substance : court and state in Nayaka period Tamilnadu. Oxford University Press. p. xix, 349 p., [16] p. of plates : ill., maps; 22 cm. ISBN 978-0-19564-399-2.

- ^ Thilakavathy, M.; Maya, R. K. (5 June 2019). Facets of Contemporary history. MJP Publishers. p. 583. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Frykenberg, Robert Eric (26 June 2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19826-377-7. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Roberts J. M. (1997). A short history of the world. Helicon Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-19511-504-8. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Wagret, Paul (1977). Nagel's encyclopedia-guide. India, Nepal. Geneva: Nagel Publishers. p. 556. ISBN 978-2-82630-023-6. OCLC 4202160.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A global chronology of conflict. ABC—CLIO. p. 756. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ S., Muthiah (21 November 2010). "Madras Miscellany: When Pondy was wasted". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Modern India:1707 A.D. to 2000 A.D. Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 94. ISBN 978-8-12690-085-5. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Madras Presidency". Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2007). World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-76147-645-0. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Gill, B. (2001). Surveying Sir George Everest (PDF) (Report). Professional Surveyor Magazine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Wallach, Bret (2005). Understanding the cultural landscape. The Guilford Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-59385-119-4. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Madras Renamed Tamil Nadu". Hubert Herald. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Murthy, Chippada Suryanarayana (1984). Andhra Martyr Amarajeevi Potti Sriramulu. International Telugu Institute.

- ^ "The reorganization of states in India and why it happened". News Minute. 2 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ V. Shoba (14 August 2011). "Chennai says it in Hindi". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Official Language Act. Parliament of India. 1963. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "Madras renamed Chennai". Maps of India. 17 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Altaff, K; J Sugumaran, Maryland S Naveed (10 July 2005). "Impact of tsunami on meiofauna of Marina beach, Chennai, India". Current Science. 89 (1): 34–38. JSTOR 24110427. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu government pegs flood damage at Rs 8,481 crore, CM Jayalalithaa writes to PM Modi". Daily News and Analysis. 23 November 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Human Development Report, Chennai (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Pulikesi, M; P. Baskaralingam; D. Elango; V.N. Rayudu; V. Ramamurthi; S. Sivanesan (25 August 2006). "Air quality monitoring in Chennai, India, in the summer of 2005". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 136 (3): 589–596. Bibcode:2006JHzM..136..589P. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.12.039. ISSN 0304-3894. PMID 16442714.

Chennai is fairly low–lying, its highest point being only 300 m (980 ft) above sea level is a rugged barren hill opposite to the Airport called Pallavapuram Hill.

- ^ "Practices and Practitioners". Centre for Science and Environment. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Quality of groundwater better this year". The Times of India. 29 January 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Lakshmi, K. (28 August 2012). "Tardy monsoon: Chennai water table rises only marginally". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Lopez, Aloysius Xavier (31 August 2018). "A Rs. 228-cr. project to take city's green cover to 20%". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ a b "How Chennai, one of the world's wettest major cities, ran out of water". The Times of India. 4 February 2021. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ a b "It's official: Chennai's rivers are 'dead'". The Times of India. 18 January 2023. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Those were the days: Buckingham Canal and its socio-political influences". Daily Thanthi. 30 August 2023. Archived from the original on 28 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Fishers mull 'people's plan' for Ennore creek restoration". The New Indian Express. 6 January 2024. Archived from the original on 28 June 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Residents along Otteri Nullah complain of pollution, health risk and flooding". The Hindu. 3 September 2023. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Raghavan, Susheela; Narayanan, Indira (2008). "Chapter 1: Geography". In S.Muthiah (ed.). Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India, Volume 1. Palaniappa Brothers. p. 13. ISBN 978-8-18379-468-8. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Lakshmi, K. (10 November 2018). "T.N. lost 41% shoreline to erosion: study". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ John, Ekatha Ann (29 September 2012). "Disaster body for panel to monitor highrises in Chennai". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Yadav, Priya (10 January 2013). "Soon, power from ancient rocks". The Times of India. Chennai. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Elbeltagi, Ahmed; Pande, Chaitanya B.; Moharir, Kanak N.; Pham, Quoc Bao; Singh, Sudhir Kumar (13 February 2023). Climate Change Impacts on Natural Resources, Ecosystems and Agricultural Systems. Springer International. p. 348. ISBN 978-3-03119-059-9.

- ^ Khan, Ansar; Akbari, Hashem; Fiorito, Francesco; Mithun, Sk; Niyogi, Dev (2022). Global Heat Island Migration. Elsevier. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-323-85539-6.

- ^ "About Chennai" (PDF). Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority. p. 28. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Heat may gradually relent over most parts of the State after June 18, says IMD". The Hindu. 15 June 2023. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Climatology tables:Extremes till 2012 (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Climatology tables:Normal 1981-2010 (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. p. 279. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Ground Water Brochure, Chennai (PDF) (Report). Central Ground Water Board, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Northeast monsoon dumps 57% excess rainfall in Tamil Nadu in 2021". Deccan Herald. 31 December 2021. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "Easterly, southeasterly winds keep city cool". The Times of India. 1 May 2007. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Northeast Monsoon, 2022 (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "NE monsoon sets in, brings in copious rains". Rediff. 12 October 2005. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ "Chennai Flooded, 2015 All Over Again! Cyclonic Storm Michaung to blame or infrastructure". Times Now. 4 December 2023. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ "Station: Chennai (Nungambakkam) Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 185–186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M192. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Table 3 Monthly mean duration of Sun Shine (hours) at different locations in India" (PDF). Daily Normals of Global & Diffuse Radiation (1971–2000). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Chennai Climatological Table 1981–2010". India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Normals Data: Chennai/Minambakkam – India Latitude: 13.00°N Longitude: 80.18°E Height: 14 (m)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ S. Theodore Baskaran (2008). "Chapter 2: Wildlife". In S. Muthiah (ed.). Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India, Volume 1. Palaniappa Brothers. p. 55. ISBN 978-8-18379-468-8. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ G. Thirumalai and S. Krishnan (July 2005). Pictorial Handbook: Birds Of Chennai. Kolkata: Zoological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Wetlands in Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ "Chennai welcomes migratory birds. Here is a guide to begin bird watching". The Hindu. 27 February 2024. Archived from the original on 28 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Good nesting season of Olive Ridley turtles ends along Chennai's coast". The Hindu. 23 May 2023. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Wildlife centre at Vandalur zoo replaces safari". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ "Madras Crocodile Bank Trust and its partner NGOs in India working to raise awareness on snakebites". The Hindu. 22 September 2013. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Shankar Raman, T. R.; R. K. G. Menon; R. Sukumar (1996). "Ecology and Management of Chital and Blackbuck in Guindy National Park, Madras" (PDF). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 93 (2): 178–192. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "Tree cover in city is only around 15%". The Hindu. Chennai. 11 February 2018. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Fisheries policy note (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Knight, J.D. Marcus; Devi, K. Rema (2010). "Species persistence: a re-look at the freshwater fish fauna of Chennai, India". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 2 (12): 1334–1337. doi:10.11609/JoTT.o2519.1334-7. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "Vanishing wetlands". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Lakshmi, K. (1 April 2018). "The vanishing waterbodies of Chennai". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ "Next time by water". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ K., Lakshmi (20 January 2019). "Indigenous flora in city wetlands under threat". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ "Adyar River pollution". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ "Couvum River pollution". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ V, Jinoy Jose P (18 June 2019). "Living without water in Chennai". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Nagarajan, Ganesh; Megson, Jody; Wu, Jin (3 February 2021). "How One of the World's Wettest Major Cities Ran Out of Water". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Muck in Chennai rivers to turn into manure". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ "More citizens initiative for restoring water bodies". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ "Water security mission to watch out for city's needs". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ H. D. Love (1913). "Population of Madras". Vestiges of Old Madras, Vol 3. p. 557.

- ^ Imperial Gazetter of India, Volume 16. Clarendon Press. 1908.

- ^ Mary Elizabeth Hancock (2008). The politics of heritage from Madras to Chennai. Indiana University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-253-35223-1.

- ^ Muthiah, S. (2004). Madras Rediscovered. East West Books (Madras) Pvt Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 81-88661-24-4.

- ^ Srivastava, Sangya (2005). Studies in Demography. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. p. 251. ISBN 978-81-261-1992-9.

- ^ Statistical handbook 2017 – 2018 (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ 2011 Census results (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Lakshmi, C. S. (1 January 2004). The Unhurried City: Writings on Chennai. Penguin Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-143-03026-3. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Bergman (2003). Introduction to Geography. Pearson Education. p. 485. ISBN 978-8-131-70210-9. Archived from the original on 29 June 2024. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Smart Cities Mission (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Chennai Corporation is re-christened Greater Chennai Corporation". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Number of people below the poverty line to increase in city". The Hindu. Chennai. 13 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Xavier Lopez, Aloysius (26 August 2017). "The shelter stalemate". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Slum Clearance plan (PDF) (Report). Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Chennai, the 2nd oldest corporation in the world". The Hindu. Chennai. 29 September 2013. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Scope of digital mapping exercise in city likely to be enlarged". The Hindu. 24 December 2011. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Chennai ward map". Greater Chennai Corporation. 12 September 2011. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Executive Chart (PDF) (Report). Greater Chennai Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Chennai to get its youngest and first Dalit woman as mayor; meet R Priya". Hindustan Times. 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.