Drake (musician)

Drake | |

|---|---|

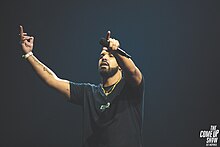

Drake in 2016 | |

| Born | Aubrey Drake Graham October 24, 1986 |

| Other names | |

| Citizenship |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 2001–present |

| Works | |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Labels | |

| Website | drakerelated |

| Signature | |

| |

Aubrey Drake Graham (born October 24, 1986) is a Canadian rapper, singer, and actor. An influential figure in popular music, he has been credited with popularizing R&B sensibilities in hip-hop artists. Gaining recognition by starring as Jimmy Brooks in the CTV teen drama series Degrassi: The Next Generation (2001–2008), Drake began his recording career in 2006 with the release of his debut mixtape, Room for Improvement (2006). He followed up with the mixtapes Comeback Season (2007) and So Far Gone (2009) before signing with Young Money Entertainment.[5]

Drake's first three albums, Thank Me Later (2010), Take Care (2011) and Nothing Was the Same (2013) each debuted atop the Billboard 200 and spawned the Billboard Hot 100-top ten singles "Find Your Love", "Take Care" (featuring Rihanna), "Started from the Bottom", and "Hold On, We're Going Home" (featuring Majid Jordan).[6] His fourth album Views (2016) lead the Billboard 200 for 13 non-consecutive weeks and contained the singles "Hotline Bling" and the US number one "One Dance" (featuring WizKid and Kyla), which has been credited for helping popularize dancehall and Afrobeats in contemporary American music.[7][8] Views was followed by the double album Scorpion (2018), which included the three US number-one singles: "God's Plan", "Nice for What", and "In My Feelings". His sixth album, Certified Lover Boy (2021), set the then-record (9) for most US top-ten songs from one album with its lead single, "Way 2 Sexy" (featuring Future and Young Thug), reaching number one. In 2022, he released the house-inspired album Honestly, Nevermind and his collaborative album with 21 Savage, Her Loss, which yielded the number-one single "Jimmy Cooks". His eighth album, For All the Dogs (2023), featured his twelfth and thirteenth number ones, "Slime You Out" (featuring SZA) and "First Person Shooter" (featuring J. Cole). In 2024, Drake was involved in a high-profile rap feud with Kendrick Lamar, producing the diss songs "Push Ups, "Taylor Made Freestyle",[a] "Family Matters", and "The Heart Part 6".

As an entrepreneur, Drake founded the OVO Sound record label with longtime collaborator 40 in 2012. In 2013, he became the "global ambassador" of the Toronto Raptors, joining their executive committee and later obtaining naming rights to their practice facility OVO Athletic Centre. In 2016, he began collaborating with Brent Hocking on the bourbon whiskey Virginia Black.[10] Drake heads the OVO fashion label and the Nocta collaboration with Nike, Inc., and founded the production company DreamCrew and the fragrance house Better World. In 2018, he was reportedly responsible for 5 percent (CAD$440 million) of Toronto's CAD$8.8 billion annual tourism income.[11]

Among the world's best-selling music artists, with over 170 million units sold, Drake is ranked as the highest-certified digital singles artist in the United States by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[12] He has won five Grammy Awards, six American Music Awards, 39 Billboard Music Awards, two Brit Awards, and three Juno Awards. He has achieved 13 number-one hits on the Billboard Hot 100, a joint-record for the most number-one singles by a male solo artist (tied with Michael Jackson).[13] Drake holds further Hot 100 records, including the most top 10 singles (78), and the most charted songs (338).[14] From 2018 to 2023, Drake held the record for the most simultaneously charted songs in one week (27), the most Hot 100 debuts in one week (22);[15] and held the most continuous time on the Hot 100 (431 weeks).[b] He additionally has the most number-one singles on the R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay, Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs, Hot Rap Songs, and Rhythmic Airplay charts.

Early life

Aubrey Drake Graham[16] was born on October 24, 1986, in Toronto, Ontario. His father, Dennis Graham, is an African-American drummer from Memphis, Tennessee, who once performed with musician Jerry Lee Lewis.[17][18] His mother, Sandra "Sandi" Graham (née Sher), is a Canadian Ashkenazi Jew, who worked as an English teacher and florist.[19][20][21][22][23] Graham performed at Club Bluenote in Toronto, where he met Sandra, who was in attendance.[18] Drake is a dual citizen of the United States and Canada, the former derived from Graham.[24][25][26] In his youth, he attended a Jewish day school and became a bar mitzvah.[27][28]

Drake's parents divorced when he was five years old. After the divorce, he and his mother remained in Toronto; his father returned to Memphis, where he was incarcerated for a number of years on drug-related charges.[29] Graham's limited finances and legal issues caused him to remain in the U.S. until Drake's early adulthood. Prior to his arrest, Graham would travel to Toronto and bring Drake to Memphis every summer.[30][31][32] Graham claimed in an interview that Drake's assertions of him being an absent father were embellishments used to sell music,[33] which Drake vehemently denies.[34]

Drake was raised in two neighbourhoods. He lived on Weston Road in Toronto's working-class west end until grade six and attended Weston Memorial Junior Public School until grade four, playing minor hockey with the Weston Red Wings.[31][35] Drake was a promising right winger, reaching the Upper Canada College hockey camp, but left at the behest of his mother following a vicious cross-check to his neck during a game by an opposing player.[36] He moved to one of the city's affluent neighbourhoods, Forest Hill, in 2000.[37][38] When asked about the move, Drake replied, "[We had] a half of a house we could live in. The other people had the top half, we had the bottom half. I lived in the basement, my mom lived on the first floor. It was not big, it was not luxurious. It was what we could afford."[39] At age 10, Drake appeared in a comedic sketch which aired during the 1997 NHL Awards, featuring a riff of Martin Brodeur and Ron Hextall and their record as being the only goalies to have scored multiple goals.[40]

He attended Forest Hill Collegiate Institute for high school,[41] and attended Vaughan Road Academy in Toronto's multicultural Oakwood–Vaughan neighbourhood; Drake described Vaughan Road Academy as "not by any means the easiest school to go to."[31] During his teenage years, Drake worked at a now-closed Toronto furniture factory owned by his maternal grandfather, Reuben Sher.[42] Drake said he was bullied at school for his racial and religious background,[43] and upon determining that his class schedule was detrimental to his burgeoning acting career, he dropped out of school.[44] Drake received his high school diploma in October 2012.[45]

Career

2001–2009: Career beginnings

At 15, Drake was introduced to a high school friend's father, an acting agent. He found Drake a role on the Canadian teen drama series Degrassi: The Next Generation, in which Drake portrayed Jimmy Brooks,[46] a basketball star who became physically disabled after he was shot by a classmate. When asked about his early acting career, Drake replied, "My mother was very sick. We were very poor, like broke. The only money I had coming in was [from] Canadian TV."[31] According to showrunners Linda Schuyler and Stephen Stohn, Drake regularly arrived late on set after spending nights recording music. To prevent this, Schuyler claimed Drake struck an agreement with the set's security guards to gain entry to the set after recording to be allowed to sleep in a dressing room.[47] Drake's first recorded song, "Do What You Do", appeared on The N Soundtrack, which was released by The N (the night-time block for Noggin), as it was the network that the series was airing on in the United States.[48]

Being musically inspired by Jay-Z and Clipse, Drake self-released his debut mixtape, Room for Improvement featuring Trey Songz and Lupe Fiasco, in 2006. Drake described the project as "pretty straightforward, radio friendly, [and] not much content to it." Room for Improvement was released for sale only and sold roughly 6,000 copies,[46] for which Drake received $304.04 in royalties.[50] He performed his first concert on August 19, 2006, at the Kool Haus nightclub as an opening act for Ice Cube, performing for half an hour and earning $100.[51] In 2007, Drake released his second mixtape Comeback Season. Released from his recently founded October's Very Own label, it spawned the single "Replacement Girl" featuring Trey Songz.[52] The song sampled "Man of the Year" by Brisco, Flo Rida and Lil Wayne, retaining Lil Wayne's verse; the rapper invited Drake to Houston to join his Tha Carter III tour.[53] On tour, Drake and Lil Wayne recorded multiple songs together, including "Ransom", "Forever", and a remix to "Brand New".[53]

In 2009, Drake released his third mixtape So Far Gone. It was made available for free download through his OVO blog website, and featured Lil Wayne, Trey Songz, Omarion, Lloyd, and Bun B. It received over 2,000 downloads in the first 2 hours of release, finding mainstream commercial success from the singles "Best I Ever Had" and "Successful", both gaining Platinum certification by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), with the former also peaking at number two on the Billboard Hot 100.[54] This prompted the mixtape's re-release as an EP, featuring four songs from the original, as well as the additions of the songs "I'm Goin' In" and "Fear". It debuted at number six on the Billboard 200, and won the Rap Recording of the Year at the 2010 Juno Awards.[55]

Due to the success of the mixtape,[56] Drake was the subject of a bidding war from various labels, often reported as "one of the biggest bidding wars ever".[57] He had secured a recording contract with Young Money Entertainment on June 29, 2009.[58] Drake joined the rest of the label's roster on the America's Most Wanted Tour in July 2009.[59] However, during a performance of "Best I Ever Had" in Camden, New Jersey, Drake fell on stage and tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee.[60]

2010–2012: Musical breakthrough with Thank Me Later and Take Care

Drake planned to release his debut album, Thank Me Later, in late 2008, but the album's release date was thrice postponed up to June 15, 2010.[61][62] On March 9, 2010, Drake released the lead single "Over",[63] which peaked at number fourteen on the Billboard Hot 100, as well as topping the Rap Songs chart. It received a nomination for Best Rap Solo Performance at the 53rd Grammy Awards.[64] His second single, "Find Your Love", became a bigger success. It peaked at number five on the Hot 100, and was certified 3× Multi-Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[65] The music video for the single was shot in Kingston, Jamaica, and was criticized by Jamaica's minister of tourism Edmund Bartlett.[66] The third single and fourth singles, "Miss Me" and "Fancy" respectively,[67] attained moderate commercial success; however, the latter garnered Drake his second nomination at the 53rd Grammy Awards for Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group.[68]

Thank Me Later was released on June 15, 2010,[69] debuting at number one on the Billboard 200 with sales of over 447,000 copies in its first week.[70] Upon the album's release, 25,000 fans gathered at New York City's South Street Seaport for a free concert hosted by Drake and Hanson, which was later cancelled by the police after a near-riot ensued due to overflowing crowds.[71] The album became the top selling debut album for any artist in 2010 and had the highest sales week for any debut album in the 2010s[72] and featured Lil Wayne, Kanye West,[73] and Jay Z.[74] Drake began his Away from Home Tour on September 20, 2010, in Miami, Florida, performing at 78 shows over four different legs.[75] It concluded in Las Vegas in November 2010.[76] Due to the tour's success, Drake hosted the first OVO Festival in 2010. Drake had an eco-friendly college tour to support the album.[77]

Drake announced his intentions to allow Noah "40" Shebib to record a more cohesive sound on his next album than on Thank Me Later.[78] In November 2010, Drake revealed the title of his next studio album would be Take Care.[79] He sought to expand on the low-tempo, sensuous, and dark sonic esthetic of Thank Me Later.[80][81] Primarily a hip-hop album, Drake also attempted to incorporate R&B and pop to create a languid, grandiose sound.[82]

In January 2011, Drake was in negotiations to join Eva Green and Susan Sarandon as a member of the cast in Nicholas Jarecki's Arbitrage,[83] before ultimately deciding against starring in the movie to focus on the album. "Dreams Money Can Buy"[84] and "Marvins Room"[80] were released on Drake's October's Very Own Blog, on May 20 and June 9, respectively. Acting as promotional singles for Take Care, the former was eventually unincluded on the album's final track listing, while "Marvins Room" gained 3× Multi-Platinum certification by the RIAA,[85] as well as peaking at number 21 on the Billboard Hot 100.[86] "Headlines" was released on August 9 as the album's lead single. It met with positive critical and commercial response, reaching number thirteen on the Hot 100, as well as becoming Drake's tenth single to reach the summit of the Billboard Hot Rap Songs.[87] It was eventually certified 4× Multi-Platinum in the United States and Platinum in Canada.[88] The music video for the single was released on October 2.[89]

Take Care was released on November 15, 2011, and received generally positive reviews from music critics.[90][91][92][93][94] It also won the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album at the 55th Annual Grammy Awards, and achieved great commercial success, eventually being certified six times platinum by the RIAA in 2019, with sales for the album marking 2.6 million in the U.S.[95] The album's third and fourth singles, "The Motto" and Take Care", were released on November 29, 2011[96] and February 21, 2012, respectively.[97] Each song achieved commercial success, and "The Motto" was later credited for popularizing the phrase "YOLO" in the United States.[98][99] The music video for "Take Care" met with widespread acclaim,[100] receiving four nominations at the 2012 MTV Video Music Awards, including for Video of the Year.[101] "HYFR" was the final single to be released from the album, and became certified 2× Multi-Platinum.[102][103]

On August 5, 2012, Drake released "Enough Said", performed by Aaliyah and himself.[104] Originally recorded prior to Aaliyah's 2001 death, Drake later finished the track with producer "40".[105] In promotion of his second album, Drake embarked on the worldwide Club Paradise Tour. It became the most successful hip-hop tour of 2012, grossing over $42 million.[106] He then returned to acting, starring in Ice Age: Continental Drift as Ethan.[107]

2013–2015: Nothing Was the Same and If You're Reading This It's Too Late

By the Club Paradise Tour's European leg, Drake had begun working on his third studio album, which he said would retain 40 as the album's executive producer, include the influence of British producer Jamie xx,[108] and stylistically differ from Take Care, departing from the ambient production and despondent lyrics previously prevalent.[109] After he won the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album at the 55th Annual Grammy Awards on 10 February 2013, Drake announced his third album, Nothing Was the Same, and released its first single.[110] The album's second single, "Hold On, We're Going Home", was released in August, peaking at number one on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart.[111] Nothing Was the Same was released on September 24, 2013, debuting at number one on the US Billboard 200, with 658,000 copies sold in its first week of release.[112] The album debuted atop the charts in Canada, Denmark, Australia and the United Kingdom. The album also enjoyed generally favourable reviews by contemporary music critics, commending the musical shift in terms of the tone and subject matter, comparing it to Kanye West's 808s & Heartbreak.[113]

The album, which sold over 1,720,000 copies in the United States, was further promoted by the "Would You like a Tour?" throughout late 2013 to early 2014.[114] It became the 22nd-most successful tour of the year, grossing an estimated $46 million.[115] Drake then returned to acting in January 2014, hosting Saturday Night Live, as well as serving as the musical guest. His versatility, acting ability and comedic timing were all praised by critics, describing it as what "kept him afloat during the tough and murky SNL waters".[116][117][118]

In late 2014, Drake announced that he began recording sessions for his fourth studio album.[119] On February 12, 2015, Drake released If You're Reading This It's Too Late onto iTunes with no prior announcement. Despite debate on whether it was an album[120] or a mixtape,[121] its commercial stance quantifies it as his fourth retail project with Cash Money Records, a scheme that was rumoured to allow Drake to leave the label.[122][123] However, he eventually remained with Cash Money, and If You're Reading This It's Too Late sold over 1 million units in 2015.[95]

2015–2017: What a Time to Be Alive, Views, and More Life

On July 31, 2015, Drake released four singles: "Back to Back", "Charged Up", "Hotline Bling", and "Right Hand". On September 20, Drake released a collaborative mixtape with Future,[124][125] which was recorded in Atlanta in just under a week.[126] What a Time to Be Alive debuted at number one on the Billboard 200, making Drake the first hip-hop artist to have two projects reach number one in the same year since 2004.[127] It was later certified 2× multi platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) for combined sales, streaming and track-sales equivalent of over 2 million units.[128] Drake announced in January 2016 that his fourth studio album would be launched during the spring, releasing the promotional single "Summer Sixteen" later that month. The album was originally titled Views from the 6, but was later shortened to Views.[129]

"Summer Sixteen" debuted at number six on the US Billboard Hot 100, and proved controversial— Drake's self-comparisons with more tenured artists divided many critics, who described his self-comparison as "goodly brash" or "conventionally disrespectful."[130][131][132] Drake soon released the album's lead singles, "Pop Style" and the dancehall-infused "One Dance", on April 5. Both debuted within the top 40 of the Billboard Hot 100;[133] however, the latter proved more commercially successful, with "One Dance" becoming Drake's first number-one single in Canada and the US as a leading artist.[134][135] The single also became Drake's first number one single as a lead artist in the United Kingdom, and peaked at number one in many other countries.[136][137]

Views was previewed in London before its premiere a day later. It was released as an Apple Music and iTunes exclusive on April 29 before being made available to various other platforms later that week.[138][139] Views would become Drake's most commercially successful album, sitting atop the Billboard 200 for thirteen weeks, as well as simultaneously leading the Billboard Hot 100 and the Billboard 200 for eight weeks. It achieved sextuple-platinum status in the U.S., and earned over 1 million album-equivalent units in the first week of its release, as well as gaining over half-billion overall streams.[140][141][142] Despite its success, critical reception was mixed: the album drew criticism for its length, lack of a cohesive theme, and dearth of artistic challenge.[143]

Drake returned to host Saturday Night Live on May 14, serving as the show's musical guest.[144] Drake and Future then announced the Summer Sixteen Tour to showcase their collective mixtape, as well as their respective studio albums.[145] The latter dates of the tour were postponed due to Drake suffering an ankle injury.[146] According to Pollstar, the Summer Sixteen Tour was the highest grossing hip-hop tour of all time, having earnt $84.3 million across 56 dates.[147] On July 23, Drake announced that he was working on a new project, scheduled to be released in early 2017.[148]

During the 2016 OVO Festival, Kanye West confirmed that he and Drake had begun working on a collaborative album.[149] Soon after, the music video for "Child's Play" was released.[150] On September 26, Please Forgive Me was released as an Apple Music exclusive. It ran a total of 25 minutes, and featured music from Views.[151] At the 2016 BET Hip-Hop Awards, Drake received the most nominations, with 10,[152] winning the awards for Album of the Year and Best Hip-Hop Video.[153][154] Drake later announced the Boy Meets World Tour on October 10.[155]

During an episode of OVO Sound Radio, Drake confirmed he would be releasing a project titled More Life, described as a "playlist of original music".[156] Drake later secured his second and third Grammy Awards, winning for Best Rap/Sung Performance and Best Rap Song at the 59th ceremony.[157] Upon release on March 18, 2017, More Life received mostly positive reviews, and debuted atop the Billboard 200, earning 505,000 album-equivalent units in its first week.[158] It also set a streaming record, becoming the highest ever streamed album in 24 hours, with a total of 89.9 million streams on Apple Music and 61.3 million on Spotify.[159] He later won a record 13 awards at the 2017 Billboard Music Awards in May.[160] By this time, Drake had been present on the Hot 100 chart for eight consecutive years, and had the most recorded entries by a solo artist.[161] Drake hosted the first annual NBA Awards on June 26,[162] and also appeared in The Carter Effect documentary.[163]

2018–2019: Scorpion and Care Package; return to television

Drake released a mini EP titled Scary Hours on January 20, 2018, marking Drake's first solo release since More Life.[164] Scary Hours featured the songs "Diplomatic Immunity" and "God's Plan", with the latter debuting at number one on the US Billboard Hot 100.[165][166][167] The song was Drake's first song as a solo artist to reach number one. It also became his first song to be certified Diamond by the RIAA,[168] and it is currently tied for the fourth highest certified digital single ever in the US[169] He was later featured on BlocBoy JB's February 2018 debut single "Look Alive".[170] The song's entry on the Hot 100 made Drake the rapper with the most top 10 hits on the Hot 100, with 23.[171]

On April 6, "Nice for What", a single from his fifth studio album, was released.[172][173] It replaced his own "God's Plan" on the Billboard Hot 100 at number one, making Drake the first artist to have a new number-one debut replace their former number-one debut. He then announced the title of his fifth studio album as Scorpion, with a planned release date of June 29, 2018.[174][175] "I'm Upset" was released on May 26 as the album's third single.[176] Scorpion was Drake's longest project, with a run-time of just under 90 minutes. The album broke both the one-day global records on Spotify and Apple Music, as it gained 132.45 million and 170 million plays on each streaming service, respectively.[177] It eventually sold 749,000 album equivalent units in its first week of sales, and debuted at number one on the Billboard 200.[178][179]

Drake earned his sixth US number-one with "In My Feelings" on July 21.[180] The success of "In My Feelings" also made Drake the record holder for most number one hits among rappers.[181] He then appeared on the Travis Scott album Astroworld, featuring uncredited vocals for the song "Sicko Mode", which peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100.[182] Drake announced in July 2018 that he planned to "take 6 months to a year" to himself to return to television and films, producing the television series Euphoria and Top Boy.[183] He then began the Aubrey & the Three Migos Tour with co-headliners Migos on August 12. This preceded a collaboration with Bad Bunny titled "Mia", which featured Drake performing in Spanish.[184]

In February 2019, he received his fourth Grammy Award for Best Rap Song, for "God's Plan", at the 61st Annual Grammy Awards.[185] During his speech, producers abruptly cut to a commercial break, leading viewers to speculate they were censoring his speech during which he criticized The Recording Academy.[186] A legal representative for the academy released a statement stating "a natural pause [led] the producers [to] assume that he was done and cut to commercial," and added the organization offered him an opportunity to return to stage, but he declined.[187]

On February 14, Drake re-released his third mixtape, So Far Gone, onto streaming services for the first time to commemorate its 10-year anniversary.[188] On June 15, Drake released two songs, "Omertà" and "Money in the Grave", on his EP The Best in the World Pack to celebrate the NBA Championship win of the Toronto Raptors.[189] On August 2, he released the compilation album Care Package, consisting of songs released between 2010 and 2016 that were initially unavailable for purchase or commercial streaming;[190] it debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 with 109,000 album equivalent units in its first week of sales.[191]

2019–2021: Dark Lane Demo Tapes and Certified Lover Boy

Drake released the song "War" on December 24, 2019, which was widely noted for its UK drill-inspired instrumental.[192][193][194] The following day, he revealed that he was in the process of completing his sixth studio album.[195] On April 3, he released "Toosie Slide" with a music video, which features a dance created in collaboration with social media influencer Toosie.[196] It debuted at number one on the Billboard Hot 100, making Drake the first male artist to have three songs debut at number one.[197] On May 1, 2020, Drake released the commercial mixtape Dark Lane Demo Tapes, with guest appearances from Chris Brown, Future, Young Thug, Fivio Foreign, Playboi Carti, and Sosa Geek.[198] The mixtape is a compilation of new songs and tracks that leaked on the internet.[199] It received mixed reviews and debuted at number two on the US Billboard 200,[200] and at number one on the UK Albums Chart.[201]

Drake also announced that his sixth studio album would be released in the summer of 2020.[202] On August 14, "Laugh Now Cry Later" featuring Lil Durk was released, which was intended as the lead single from the upcoming album Certified Lover Boy,[203] but not included on the final track listing. It debuted at number two on the Hot 100, and was nominated for Best Rap Song at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards. On his 34th birthday, Drake announced Certified Lover Boy was set to be released in January 2021.[204][205] This was later pushed back after he sustained a serious knee injury.[206]

In January 2021, Drake became the first artist to surpass 50 billion combined streams on Spotify.[207] On March 5, Drake released an EP titled Scary Hours 2, which includes three songs: "What's Next", "Wants and Needs" with Lil Baby, and "Lemon Pepper Freestyle" with Rick Ross.[208] These three songs entered the charts at numbers one, two, and three, respectively, making Drake the first artist to have three songs debut in the top three on the Billboard Hot 100.[209] He was named Artist of the Decade at the 2021 Billboard Music Awards.[210]

Certified Lover Boy was released on September 3, 2021, becoming Drake's tenth number-one album on the Billboard 200;[211] every song debuted on the Billboard Hot 100, while the album was the first to chart nine songs in the top 10, with "Way 2 Sexy" becoming Drake's ninth number-one single.[212][213] Certified Lover Boy was nominated for Best Rap Album and "Way 2 Sexy" was nominated for Best Rap Performance at the 64th Annual Grammy Awards.[214] He was later named Billboard's Top Artist of the Year for 2021,[215] and was the fourth most streamed artist on Spotify for the year, and the most streamed rapper.[216] On December 6, he withdrew his music for consideration for the Grammys, with multiple outlets noting his contentious relationship with the Recording Academy.[217] Drake accumulated 8.6 billion on-demand streams in 2021, making him the most overall streamed artist of the year in the United States; one out of every 131 streams was a Drake song.[218]

2022–present: Honestly, Nevermind, Her Loss, For All the Dogs and Kendrick Lamar feud

On March 3, 2022, Drake placed fourth on Forbes's ranking of highest paid rappers of 2021, with an estimated pre-tax income of $50 million.[219] On April 16, it was calculated Drake generated more streams in 2021 than every song released prior to 1980 combined; his music accumulated 7.91 billion streams, while songs pre-1980 had generated 6.32 billion.[220] Drake was then confirmed as a guest artist on Future's I Never Liked You (2022); one of the songs he featured on, "Wait for U", debuted atop the Billboard Hot 100, becoming Drake's tenth number-one song and making him the tenth act to achieve ten number ones.[221]

In early May, Drake re-signed with Universal Music Group in a multifaceted deal reported to be worth as much as $400 million, making it one of the largest recording contracts ever.[222] On June 16, Drake announced his seventh album, Honestly, Nevermind, which released a day later; he also announced a third iteration of his Scary Hours EP series.[223] Honestly, Nevermind sold 204,000 album-equivalent units in its first week, becoming Drake's eleventh US number-one album and making him the fifth artist with over 10 number one albums, after the Beatles (19), Jay-Z (14), Bruce Springsteen, and Barbra Streisand (both 11).[224] "Jimmy Cooks" also became Drake's eleventh US number-one song.[225]

On July 14, it was announced Drake would reunite with Lil Wayne and Nicki Minaj on a Toronto exclusive concert series on July 28, July 29, and August 1.[226] After the debut of "Staying Alive" on the US Billboard Hot 100, it marked the 30th Drake song to reach the top five on the chart, breaking a 55-year-old record for most songs to reach the top five on the chart (29), held by the Beatles.[227] Drake refused to submit his music for Grammy consideration for a second consecutive year.[228]

On October 22, Drake announced Her Loss, a collaborative album with 21 Savage which would release on October 28;[229] it was then delayed to November 4 after Drake's longtime producer, 40, was diagnosed with COVID-19.[230] Her Loss debuted atop the Billboard 200, accumlating first week sales of 404,000 album-equivalent units. Eight of the album's songs debuted in the top ten on the Billboard Hot 100, extending Drake's record for most top ten entries, with 67 (with a record 49 as a lead artist).[231] On November 15, Drake was nominated for four awards at the 2023 Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year for his writing on Beyoncé's Renaissance.[232] In February 2023, Drake was named the most streamed act ever on Spotify.[233]

On July 23, via an announcement for his poetry book Titles Ruin Everything, Drake announced his eighth studio album, titled For All the Dogs.[234] On September 15, Drake released the lead single of the album, "Slime You Out", featuring SZA.[235] The song charted at number one on the US Billboard Hot 100.[236] On October 5, Drake released the album's second single, "8AM in Charlotte", on his social media accounts.[237] On September 16, Drake released For All The Dogs, which debuted atop the Billboard 200. On March 8, 2024, Drake remixed "Act II: Date @ 8" with 4Batz via OVO Sound.[238][239]

On March 22, 2024, Kendrick Lamar dissed Drake, as well as J. Cole, on Future and Metro Boomin's song "Like That", beginning the feud.[240] During this time, there were also other disses toward Drake from Future, ASAP Rocky, and The Weeknd.[241] On April 19, 2024, Drake released "Push Ups" after early versions were leaked online as a response track whilst also addressing Future and Rick Ross, followed up with "Taylor Made Freestyle" later that day. On April 30, 2024, Lamar released a diss track named "Euphoria" in response, as well as "6:16 in LA" on May 3, 2024, exclusively on Instagram. That same day, Drake released "Family Matters" exclusively on YouTube in response. Lamar released "Meet the Grahams" 20 minutes later, and would go onto release "Not Like Us" the following day.[242] On May 5, Drake released "The Heart Part 6", a reference to Lamar's 2022 track "The Heart Part 5".[243]

In June 2024, Drake made an appearance on the second verse of the social media personality Snowd4y's "Wah Gwan Delilah", a parody inspired by the 2006 Plain White T's hit, "Hey There Delilah".[244]

On August 2, 2024, Drake appeared as an unannounced guest at the Toronto stop on PartyNextDoor's tour.[245] Following his performance, consisting of solely his R&B songs, he announced a collaborative album between himself and Party, "On behalf of me and Party, we've been working on something for y'all. So, you get the summer over with, you do what you need to do. I know all you girls are outside. When it gets a little chilly, PartyNextDoor and Drake album will be waiting right there for you".[245][246] On August 4, through the OVO Sound Instagram page, the album's name, Hometown Love was teased.[247] On August 6, OVO Sound published a link to a website with three new Drake songs: "It's Up" featuring 21 Savage, "Blue Green Red", and "Housekeeping Knows" featuring Latto.[248]

Artistry

Influences

Drake has cited several hip-hop artists as influencing his rapping style, including Kanye West,[249] Jay-Z,[250] MF Doom,[251] and Lil Wayne,[252] while also attributing various R&B artists as influential to the incorporation of the genre into his own music, including Aaliyah[253] and Usher.[254] Drake has also credited several dancehall artists for later influencing his Caribbean-inflected style, including Vybz Kartel, whom he has called one of his "biggest inspirations".[255][256]

Musical style

Drake is considered to be a pop rap artist.[257] While Drake's earlier music primarily spanned hip-hop and R&B, his music has delved into pop and trap since the albums Nothing Was the Same (2013) and Views (2016).[258] Additionally, his music has drawn influence from regional scenes, including Jamaican dancehall[256] and UK drill.[194] Drake is known for his egotistical lyrics, technical ability, and integration of personal backstory when dealing with relationships with women.[259] His vocal abilities have been lauded for an audible contrast between typical hip-hop beats and melody, with sometimes abrasive rapping coupled with softer accents, delivered on technical lyricism.[260]

His songs often include audible changes in lyrical pronunciation in parallel with his upbringing in Toronto, and connections with Caribbean and Middle Eastern countries which include such phrases as "ting", "touching road", "talkin' boasy" and "gwanin' wassy".[260] Most of his songs contain R&B and Canadian hip-hop elements, and he combines rapping with singing.[261] He credits his father with the introduction of singing into his rap mixtapes, which have become a staple in his musical repertoire. His incorporation of melody into technically complex lyrics was supported by Lil Wayne, and has subsequently been a critical component to Drake's singles and albums.[262] Drake's style of R&B is characterized by vacant beats and a rap-sung dichotomy, which has also seen incredible mainstream success, spawning several imitators.[263]

The lyrical content that Drake deploys is typically considered to be emotional[264] or boastful.[265] However, Drake is often revered for incorporating "degrading" themes of money, drug use, and women into newer, idealized contexts, often achieving this through his augmentation of the typical meaning of phrases in which he combines an objective and subjective perspective into one vocal delivery. His songs often maintain tension between "pause and pace, tone timbre, and volume and vocal fermata."[266] Drake is credited with innovating what has been referred to as "hyper-reality rap", characterized by its focus on themes of celebrity as distinct from the "real world."[267]

Public image

Drake's lyrical subject matter, which often revolves around relationships, have had widespread use on social media through photo captions to reference emotions or personal situations.[268] However, this content has incited mixed reception from fans and critics, with some deeming him as sensitive and inauthentic, traits perceived as antithetical to traditional hip-hop culture.[269][270] He is also known for his large and extravagant lifestyle, including for high-end themed birthday parties;[271] he maintained this image in his early career by renting a Rolls-Royce Phantom, which he was eventually gifted in 2021.[272] He cultivated a reputation as a successful gambler; between December 2021 and February 2022, he was reported to have made bets of over $1 billion, which included winnings ranging between $354,000 and $7 million,[273] however some of the forms of gambling he promotes, such as roulette, have negative expected values.[274]

The Washington Post editor Maura Judkis credits Drake for popularizing the phrase "YOLO" in the United States with his single "The Motto", which stands for, "You only live once."[275] Drake later popularized the term "The Six" in 2015 in relation to his hometown Toronto, subsequently becoming a point of reference to the city.[276] June 10 was declared "Drake Day" in Houston.[277][278][279] In 2016, Drake visited Drake University after a show in Des Moines in response to an extensive social media campaign by students that began in 2009, advocating for his appearance.[280][281] According to a report from Confused.com, Drake's Toronto home was one of the most Googled homes in the world, recording over a million annual searches in 2021; its features, such as its NBA-size indoor basketball court and Kohler Numi toilet, have also received widespread media attention.[282]

The music video for "Hotline Bling" went viral due to Drake's eccentric dance moves.[283] The video has been remixed, memed, and was heavily commented on due to the unconventional nature on the song,[284] causing it to gain popularity on YouTube, and spawning several parodies.[285] Drake has also been critiqued for his expensive, product placement-heavy attire, exemplified by the video for "Hotline Bling". Drake modelled a $1,500 Moncler Puffer Jacket, a $400 Acne Studios turtleneck, and limited edition Timberland 6" Classic Boots.[286][287] He was labeled by GQ magazine as "[one of] the most stylish men alive";[288] during promotion for Certified Lover Boy, Drake debuted a "heart haircut", which became popular and widely imitated.[289] Writing for GQ, Anish Patel noted Drake's consistent incorporation of styles and themes not typically associated with hip-hop, such as wearing gorpcore in the music video for his song "Sticky".[290] Since 2016 Drake has been noted for an alleged "Drake curse", an internet meme based on the incidents where he appears to be support of particular sports team or person, just for that team or person to lose, often against the odds.[291][292]

In 2016, Drake discussed the shooting of Alton Sterling, publishing an open letter expressing his concern for the safety of ethnic minorities against police brutality in the United States.[293] In 2021, he joined a group of Canadian musicians to work with the Songwriters Association of Canada (SAC) to lobby Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to restructure the country's copyright law to allow artists and their families to regain ownership of copyrights during their lifetime.[294] He also campaigned for the expansion of a Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) franchise in Toronto,[295] and headlined a benefit concert at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum with Kanye West on December 9, 2021, to raise clemency for Larry Hoover,[296] although his solo performance was later removed from the Prime Video replay.[297] On Christmas 2021, Drake gave away money to individuals in Toronto.[298] In October 2023, he signed a letter calling for a ceasefire in the Israel–Hamas war.[299]

Impact

A prominent figure in pop culture,[300] Drake is often praised one of the most influential figures in hip-hop;[301] particularly his use of singing over hip-hop instrumentals has been noted as an influence on modern rappers.[302] He is widely credited for popularizing the Toronto sound to the music industry and leading the "Canadian Invasion", a play on the British Invasion in the 1960s, of the American charts—alongside the likes of Justin Bieber and the Weeknd.[303][304][305][306][307] In 2022, music recognition app Shazam revealed Drake to be their most searched artist by users, with music featuring Drake collecting 350 million recognitions; his 2016 single "One Dance" collected 17 million recognitions alone.[308] In 2018, articles by The Guardian and Rolling Stone called him "the definitive pop star of his generation" and "perhaps [the] biggest post-Justin Timberlake male pop star of the new millennium", respectively.[309][310]

The Insider declared Drake the artist of the decade (2010s).[301] Regarding the general view that Drake introduced singing in mainstream hip-hop, the publication said that at the height of Auto-Tune in hip-hop during the late 2000s, "there were virtually no artists who were both a legit rapper and a legit crooner who delivered velvety smooth pop/R&B hybrid vocals that could exist separately from his hip-hop songs."[301] Commenting on Drake's Take Care, Elias Leight of Rolling Stone noticed in 2020 that "now nearly every singer raps, and nearly every rapper sings", as many artists "have borrowed or copied the template of [the album] that the boldness of the original is easily forgotten", according to the writer.[311]

Aaron Williams of Uproxx added "jump-starting the sad boy rapper craze alongside Kid Cudi" and "helping to renew stateside interest in UK grime and Caribbean dancehall with Skepta, PartyNextDoor, and Rihanna" to the modern trends Drake assisted.[312] BBC Radio 1Xtra argued that his co-signs helped push the British hip-hop scene to a wider international market, as he did with the Toronto music scene.[313] According to CBS Music in 2019, Drake has inspired "the next wave" of artists coming out of his hometown.[314] Writing for Bloomberg, Lucas Shaw commented Drake's popularity has influenced the promotion of music, with Certified Lover Boy attaining large commercial success despite relatively minimal orthodox marketing techniques, stating "fans are consuming Drake's [music] in a way that is different to others".[315] He also noted the album as novel in relation to consumption, with each song having relatively equivalent streams, as opposed to a dominant single(s).[315] Justin Charity of The Ringer noted Drake's signature of producing "half-hearted" performances on songs to create a "natural and off-the-cuff" effect has become the "obvious touchpoint for [subsequent] male R&B singers".[263] Charity further wrote Drake's success in the genre is "so thorough that it's all but impossible to hear certain vintages of R&B without hearing Drake".[263]

Beginning in 2022, Drake's music was canonized academically by Toronto Metropolitan University, which began teaching courses titled "Deconstructing Drake and the Weeknd", with the pair's music used to explore themes related to the Canadian music industry, race, class, marketing and globalization.[316] With the release during LGBT Pride Month of his seventh album Honestly, Nevermind (2022), Mark Savage of the BBC wrote Drake's exploration of house, a genre with overt origins in black and queer spaces, would help "build a bridge to those [origin] subcultures" for younger music listeners.[317]

Achievements

Drake is the highest-certified digital singles artist ever in the United States, having moved 142 million units based on combined sales and on-demand streams.[12][318] His highest-certified single is "God's Plan" (15× Platinum), followed by "Hotline Bling" and "One Dance", which are certified Diamond.[319] Drake was Spotify's most streamed artist of the 2010s.[320]

He holds several Billboard Hot 100 chart records; he has the most charted songs of any artist (338),[14][321] the most top 10 singles (78),[14][321] the most top 10 debuts (62),[14][321] the most top 10 singles in a calendar year (13),[14][321] the most cumulative weeks in the top 10 (387),[14][321] the most songs peaking at number-two (10) (11 including his appearance as a member of Young Money on "BedRock"),[14][321] and the most consecutive weeks spent on the chart (431 weeks).[14][321] He has accumulated 13 number-one songs (14 including his uncredited feature on "Sicko Mode"), a record among rappers.[322] In 2021, Drake became second act to occupy the entire Hot 100's top five in a single week, the other act being the Beatles in 1964.[213] He also has the most number-one singles on the Hot Rap Songs (23), Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs (23),[213] and Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay.[323] He is also the only artist to have two albums log 400 weeks each on the Billboard 200.[324]

As of 2021[update], Drake has won four Grammy Awards from 47 nominations.[325] He has also won a record 29 Billboard Music Awards. In 2017, he surpassed Adele's record for most wins at the Billboard Music Awards in one night, winning 13 awards from 22 nominations.[160] He was named Artist of the Decade at the 2021 Billboard Music Awards.[210] Billboard editor Ernest Baker stated "Drake managed to rule hip-hop in 2014", adding "the best rapper in 2014 didn't need a new album or hit single to prove his dominance".[326] From 2015 to 2017, Drake ranked within the top-five of the Billboard Year-End chart for Top Artists,[327][328][329] before topping it in 2018.[330] He was named the IFPI Global Recording Artist of 2016 and 2018.[331]

Pitchfork ranked Nothing Was the Same as the 41st best album of the decade "so far"—between 2010 and 2014,[332] and ranked him fifth in the publication's list of the "Top 10 Music Artists" since 2010.[333][334] Take Care was ranked at number 95 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (2020).[311] He has been ranked by Complex on their "Best Rapper Alive Every Year Since 1979" list, awarding Drake the accolade in 2011, 2012, and 2015.[335]

Controversies

Legal issues

In 2012, singer Ericka Lee filed a lawsuit against Drake for the usage of her voice on "Marvins Room". Claiming to have provided the female vocals, Lee also alleged she was owed songwriting credits and royalties.[336] Despite Drake's legal team countering by claiming that Lee simply requested a credit in the liner notes of the album, the matter was resolved in February 2013, with both parties agreeing to an out-of-court settlement.[337] Also in 2012, Drake caused a nightclub in Oklahoma City to close down, due to his usage of marijuana and other illegal drugs being prevalent at the club.[338] In 2014, Drake was sued for $300,000 for sampling "Jimmy Smith Rap", a 1982 single by jazz musician Jimmy Smith. The suit was filed by Smith's estate, who said Drake never asked for permission when sampling it for the intro on "Pound Cake / Paris Morton Music 2", claiming Smith himself would have disagreed as he disliked hip-hop.[339][340] Drake would win the lawsuit in 2017, with federal judge William Pauley ruling the content used was transformative, and there was no liability for copyright infringement.[341] Also in 2014, it emerged that Drake was sued by rapper Rappin' 4-Tay, claiming Drake misused his lyrics when collaborating with YG on the song "Who Do You Love?". He sought $100,000 for mistreatment and artistic theft, which Drake paid to the rapper later that year.[342]

In December 2021, Drake sued jeweler Ori Vechler and his company Gemma LTD for incorrectly using his likeness in promotional material; he also sought to return three items he purchased.[343] In December 2022, a lawsuit brought by rapper Angelou Skywalker, who alleged that Drake stole his song "Reach for Skies" to make "Way 2 Sexy", was dismissed following "repeated misconduct" by Skywalker against prosecutors and U.S. district judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly, who presided over the case; Skywalker was accused of filing no less than 50 irrelevant motions and was handed a restraining order, preventing contact with Drake.[344]

In 2017, Drake was embroiled in another lawsuit, being sued by producer Detail (Noel Fisher) over an alleged assault in 2014. Fisher claimed Drake's bodyguard, Nessel "Chubbs" Beezer, punched him in the face and allegedly broke his jaw over musical and financial disputes. Fisher also said the injuries caused him to be hospitalized for days and had to undergo several surgeries, following which he sued for damages related to medical bills and physical and emotional suffering.[345] The case, which was set to undergo trial in May 2018, was dismissed by Superior Court Judge Elaine Lu after Fisher failed to show up for a final status conference. Lu ruled that Beezer solely acted in self-defense.[346]

In January 2019, Drake, Odell Beckham Jr., and Younes Bendjima were sued by a man named Bennett Sipes in regards to an alleged assault that occurred outside of a L.A. nightclub in 2018. Sipes claims he suffered "traumatic brain injury, as well as injuries to his back, neck, shoulders, etc." on March 24, 2018, when he was attacked by Bendjima, as well as members of Drake and Beckham's entourages in an alley near the nightclub and sought $250,000 in damages. The suit alleges Drake and Beckham followed their respective crews to the alley to watch Sipes get attacked. A video of the incident was recorded using the on-site surveillance system.[347] The suit was eventually settled out of court.[348] In 2019, Drake paid a $350,000 settlement to a woman who alleged that he sexually assaulted her. Drake denied the allegations.[349]

In October 2021, Drake and Chris Brown were sued by Braindon Cooper and Timothy Valentine for copyright infringement between "No Guidance" and their own song "I Love Your Dress",[350][351][352] but Drake was dropped by Cooper and Valentine from the lawsuit in April 2022.[353] Drake was handed another copyright lawsuit from Samuel Nicholas, citing infringement from Drake's "In My Feelings" and "Nice for What".[354] That November, he was named co-defendant with Travis Scott in a multi-claimant lawsuit for inciting "a riot and violence" at the Astroworld Festival,[355] to which he released a statement;[356] he reportedly delayed the release of "Splash Brothers", a collaboration with French Montana, as a result.[357]

On July 14, 2022, Drake was detained by Swedish police, reportedly stemming from drugs present within a Stockholm nightclub.[358] That November, Drake and 21 Savage were sued by Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue, for using the Vogue name without permission to promote their collaborative album Her Loss;[359][360] Drake and 21 Savage "voluntarily ceased" to a preliminary injunction to stop using Vogue trademarks to promote the album,[361] and later reached a settlement with Condé Nast.[362] In February 2023, Drake was ordered to appear for a deposition in the XXXTentacion murder trial after the defense team for Dedrick Williams — one of the three suspects — listed Drake as a potential witness, related to the purported feud between Drake and XXXTentacion; Drake was subpoenaed the month prior, and failed to show for his scheduled deposition date of January 27; the rescheduled deposition was set for February 24.[363] It was later reported that armed guards at Drake's Beverly Hills home refused to accept the service of the deposition on February 14, which Drake's lawyer, Bradford Cohen, argued was not properly served in compliance with California law and done solely to "inject celebrity spectacle in a routine trial", ultimately leading to the deposition being dismissed.[364]

Feuds

Drake and Chris Brown were allegedly involved in a physical altercation in June 2012 when Drake and his entourage threw glass bottles at Brown in a SoHo nightclub in Manhattan, New York City. Chris Brown tweeted about the incident, and criticized Drake in music until 2013, including on the "R.I.P." remix.[365][366][367] Despite no response from Drake, he and Brown both appeared in a comedic skit for the 2014 ESPY Awards, and rehearsed the skit together prior to the televised airing, virtually ending the dispute.[368] The pair later collaborated on "No Guidance" in 2019.[369]

The Drake-Kendrick Lamar feud was identified by media outlets from 2013, alleging several songs to be sneak disses by both parties. Lamar first dissed Drake and other rappers on the song "Control" in 2013, but stated his verse was intended to be seen as "friendly competition": Drake and Lamar previously collaborated on songs and Lamar featured as Drake's opening act on the Club Paradise Tour in 2012. Lamar dissed Drake and J. Cole in 2024, with Drake and J. Cole's 2023 song "First Person Shooter" alleged to be a sneak diss. Drake responded on the songs "Push Ups" and "Taylor Made Freestyle", of which, Lamar responded with "Euphoria" and "6:16 in LA". Drake then released "Family Matters", accusing Lamar of domestic abuse and alleging one of Lamar's children was fathered by Dave Free. Lamar first replied with "Meet the Grahams", accusing Drake of sex crimes and fathering a secret child, and then with "Not Like Us", accusing Drake of pedophilia and anti-black sentiment. Drake responded with "The Heart Part 6", denying Lamar's accusations and claiming he gave Lamar false information about the secret child.[370]

In December 2014, Drake was involved in another altercation, being punched by Puff Daddy outside the LIV nightclub in Miami. The altercation was reported to be over Drake's usage of the instrumental for "0 to 100 / The Catch Up", allegedly produced by Boi-1da for Puff Daddy, before Drake appropriated it for himself. Drake was rushed to the ER after aggravating an old arm injury during the dispute.[371] Drake was also involved in a feud with Tyga, stemming from Tyga's negative comments about him during an interview with Vibe magazine.[372] Drake would later respond on "6 God" and "6PM in New York", which has been interpreted as directly involved in Tyga's abrupt removal from Young Money Entertainment.[373]

Controversy arose in July 2015 when Meek Mill alleged that Drake had used ghostwriters for his verse on "R.I.C.O.". This was followed by further allegations that Drake did not help promote the song because Meek Mill discovered the ghostwriter, whom he revealed to be Quentin Miller.[374] Despite Miller receiving past writing credits, Funkmaster Flex aired reference tracks by Miller, who was revealed to have helped write "R.I.C.O.", "10 Bands", and "Know Yourself". This prompted Drake to respond with two diss tracks: "Charged Up" and "Back to Back",[375][376] in the space of four days. Meek Mill responded with "Wanna Know",[377] before removing it from SoundCloud weeks later.[378] Following several subliminal disses[379][380][381] from either artist,[382] Drake further sought to denounce Funkmaster Flex while performing in New York (Flex's home state) on the Summer Sixteen Tour.[383][384] After Meek Mill's 2017 prison sentence for probation violation, Drake stated "Free Meek Mill" at a concert in Australia, and ended their rivalry on "Family Feud" in 2018;[385] the pair later collaborated on "Going Bad" in 2019.[386]

Pusha T would use the same rationale to diss Drake on "Infrared" in 2018,[387] leading Drake to respond with the "Duppy Freestyle" diss track on May 25.[388] Pusha T responded with "The Story of Adidon" on May 29, which presented several claims and revealed Drake's fatherhood.[389] The pair are considered to have been in a rivalry since 2012, resulting from Pusha T's feuds with Lil Wayne and Birdman, with Drake yet to respond to "The Story of Adidon".[390]

In 2016, Drake was embroiled in a feud with Joe Budden, stemming from Budden's derogatory comments when reviewing Views. Drake would allegedly respond to Budden through "4PM in Calabasas", prompting Budden to respond with two diss tracks in the space of five days, echoing the same sentiment Drake deployed during his feud with Meek Mill. Drake would later appear on "No Shopping" alongside French Montana, directly referencing Budden throughout the song, although, Montana claimed Drake's verse was recorded before the release of Budden's diss tracks. Despite Budden releasing two further songs in reference to Drake,[391] he has yet to officially respond to Budden.[392] In the same year, Drake dissed Kid Cudi on "Two Birds, One Stone" after Cudi launched an expletive-filled rant on the artist on Twitter.[393] Cudi later checked into a rehabilitation facility following the release of the song, and continued to disparage Drake in further tweets;[394] the pair eventually resolved their feud, and collaborated on "IMY2" in 2021.[395]

In mid-2018, Drake was embroiled in a feud with long-time collaborator Kanye West.[396] In an appearance on The Shop, Drake recounted several meetings with West, who voiced his desire to "be Quincy Jones" and work with Drake and replicate the producer-artist relationship between Jones and Michael Jackson.[397] West requested Drake play and inform him of upcoming releases, while he gave Drake the instrumental to "Lift Yourself".[398] West requested the pair work in Wyoming, with Drake arriving a day after close friend 40, who said West was instead recording an album. Judging the pair to have differing release schedules, Drake traveled to Wyoming,[399] but "only worked on [West's] music"; they explored Drake's after he played West "March 14", which addressed Drake's relationship with his newborn son and co-parent.[400] This prompted a conversation with West regarding his personal issues, after which, news of his son would be exposed by Pusha T,[401] which Drake concluded was revealed to him by West; West also released "Lift Yourself" as a solo song and produced "Infrared". Drake then denounced West in songs and live performances.[402][403] West would retaliate in a series of tweets in late 2018, and the pair continued to respond on social media and in music as of late 2021,[404] which included Drake leaking West's song "Life of the Party".[405] During their feud, West and Drake have had public attempts of reconciliation,[406] which is reported to have occurred after they co-headlined a benefit concert in December 2021.[407]

Drake has been involved in reported feuds with DMX, music critic Anthony Fantano,[408][409][410] Common,[411] the Weeknd,[412] XXXTentacion, Jay-Z, Tory Lanez,[413] and Ludacris,[414] although the latter three, as well as his feud with DMX, have been reported to be resolved.[415][416][417]

Business ventures

Endorsements

Prior to venturing into business, Drake garnered several endorsement deals with various companies, notably gaining one with Sprite following his mention of drinking purple drank, a concoction that contains Sprite as a key ingredient.[418][419] In the aftermath of his highly publicized feud with Meek Mill, Drake was also endorsed by fast food restaurants Burger King, White Castle and Whataburger.[420] Business magazine Forbes commented his endorsement deals and business partnerships "combined heavily" for Drake's reported pre-tax earnings at $94 million between June 2016 to June 2017, being one of the highest-paid celebrities during that period.[421] Drake receives an endorsement of $100 million per annum from the gambling firm Stake.com, as an ambassador of the online casino.[422] The partnership with Stake.com has created "The Drake Effect", which has increased the company's awareness.[423][424] Drake has frequently posted about his bets on Stake and created content related to playing roulette on the platform.[425] In January 2022, Drake announced Stake's two-year naming sponsorship of the Sauber Formula 1 (F1) racing team, which began in 2024.[426]

OVO Sound

During the composition of Nothing Was the Same, Drake started his own record label in late 2012 with producer Noah "40" Shebib and business partner Oliver El-Khatib. Drake sought for an avenue to release his own music, as well helping in the nurturing of other artists, while Shebib and El-Khatib yearned to start a label with a distinct sound, prompting the trio to team up to form OVO Sound.[427] The name is an abbreviation derived from the October's Very Own moniker Drake used to publish his earlier projects. The label is currently distributed by Warner Bros. Records.

Drake, 40, and PartyNextDoor were the label's inaugural artists. The label houses artists including Drake, PartyNextDoor, Majid Jordan, Roy Woods, and dvsn,[428] as well as producers including 40, Boi-1da, Nineteen85, and Future the Prince.

Toronto Raptors

On September 30, 2013, at a press conference with Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment CEO Tim Leiweke,[429] Drake was announced as the new "global ambassador" of the Toronto Raptors, joining the executive committee of the NBA franchise. It was announced together with the 2016 NBA All-Star Game being awarded to the Air Canada Centre in Toronto.[430][431][432] This was also the setting where Drake was given The Key to the City.[433] In the role, it was announced that Drake would help to promote and serve as a host of festivities, beginning with the All-Star Game. He would also provide consulting services to rebrand the team, helping to redesign its image and clothing line in commemoration of the franchise's 20th anniversary.[429][434][435][436] He also collaborated with the Raptors on pre-game practice jerseys, t-shirts, and sweatsuits,[437] and began hosting an annual "Drake Night" segment with the organization, beginning in 2013.[438]

Entertainment

Apple Music

Following the launch of Apple Music, a music and video streaming service developed by Apple Inc., the company announced Drake as the figurehead for the platform at their Worldwide Developers Conference in 2015, with the artist also penning an exclusivity deal with the service worth a reported $19 million.[439] This saw all future solo releases by Drake becoming available first on Apple Music, before seeing roll out to other streaming services and music retailers.[440] Drake had also developed the OVO Sound Radio station on Beats 1, which is utilized as the primary avenue for debuting singles and projects, with the station overseeing over 300 million unique users when it debuted More Life.[441] Drake's partnership with Apple Music has largely been credited for the platform's sharp success, as it attained 10 million subscribers after six months, as well as giving birth to exclusivity from artists, with many independent and signed artists, such as Frank Ocean and the Weeknd, also brokering exclusivity deals with streaming services.[442] Through signing with the company, Drake was one of the artists, alongside Pharrell and Katy Perry, to exclusively own an Apple Watch before the smartwatch saw public release.[443]

DreamCrew and investments

In 2017, Drake and Adel "Future" Nur co-founded the production company DreamCrew, with functions in both management and entertainment. The company has produced the television series Euphoria and Top Boy.[444] Their debut produced film was sports documentary The Carter Effect, detailing the impact of Vince Carter in Canada.[445] On August 5, 2022, Drake was among those nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Drama Series for acting as a producer on Euphoria.[446]

In July 2021, Drake was announced as an executive producer, alongside LeBron James and Maverick Carter, for Black Ice, a documentary film charting the experiences of black and ethnic minority professional and amateur ice hockey players. It is due to be produced by Uninterrupted Canada in partnership with Drake's DreamCrew Entertainment, James' SpringHill Company, and Bell Media.[447] DreamCrew also began production on the unscripted survival series Chillin' Island in 2021, due to air on HBO.[448] In June 2021, Live Nation confirmed a long-standing partnership with Drake to open History, a 2,500 convertible capacity live-entertainment and general function venue in Toronto. It was in development for over three years and is situated in The Beaches.[449] He also aided in the venue's interior design, which contains LED screens, soundproofing, quick-change rooms and a customizable staircase.[450] In November 2022, DreamCrew invested near-$100 million to revive the open-air museum and amusement park Luna Luna; originally staged in Hamburg, it is set to go on a worldwide tour, with Drake stating, "[Luna Luna] is such a unique and special way to experience art. This is a big idea and opportunity that centers around what we love most: bringing people together".[451]

Drake signed as an investor and collaborator with Los Angeles-based sustainability and financial services startup Aspiration; he will also use the company's enterprise services to monitor and ensure personal carbon neutrality.[452] He has also invested in robo-advisor Wealthsimple, the "livestreaming video commerce platform" NTWRK, the cannabis provider Bullrider, and several sports-related ventures, including online esports betting platform Players' Lounge, the sportstech firm StatusPro, and online sports network Overtime.[453] In an analysis by Brennan Doherty for Toronto Star, Drake's investment "carry all the hallmarks" typical of musicians, which is often momentum investing, and cited Jason Pereira, who described Drake's business deals as typically angel investing and private equity (often venture capital) funds. Pereira also noted his "leveraging his personal brand to generate cash".[453] On August 30, 2022, it was reported that Drake and LeBron James, as part of the investment fund Main Street Advisors, would partner with U.S. private equity group RedBird Capital and Yankee Global Enterprises to purchase Italian soccer club AC Milan for a rumored $1.2 billion.[454] As a minority shareholder in the club, he is one of a group of investors who hold a 0.07% stake.[455] Drake has also invested in cryptocurrency and NFT payment solutions firm MoonPay.[456]

100 Thieves

In 2018, Drake purchased an ownership stake in the gaming organization 100 Thieves, joining as a co-founder and co-owner. The investment was partly funded by music executive Scooter Braun and Cleveland Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert.[457][458]

Cuisine

Two months prior to the release of Views, Drake announced the development of Virginia Black, a bourbon whiskey.[459] This would be his second foray into selling foodstuffs, previously partnering with celebrity chef Susur Lee to open Fring's Restaurant and Antonio Park to open the sports bar Pick 6ix, both in Toronto and eventually closed.[460][461] Virginia Black was created and distributed by Proximo Spirits and Brent Hocking,[462] a spirits producer who founded DeLeón Tequila in 2008.[463] The company described the partnership as "fruitful [as they] share a passion for style, music, and the pursuit of taste [on] a quest to redefine whiskey."[464] In 2021, using ratings compiled from Vivino and complimentary website Distiller, Virginia Black was ranked the worst value celebrity liquor for quality and price.[465]

The product was launched in June 2016, and contained two, three and four-year old Bourbon whiskies. The company sold over 4,000 bottles in the first week domestically.[466] The brand was also promoted and marketed through Drake's music and various tours, such as being part of the "Virginia Black VIP Lounge" additional package available for purchase during the Summer Sixteen Tour. Virginia Black shipped a further 30,000 units when rollout was extended to select international markets in late 2016.[467] The company later aired commercials with Drake's father, Dennis Graham, which featured the mock tagline of "The Realest Dude Ever" (in reference toward "The Most Interesting Man in the World" tagline employed by Dos Equis) after extending the sale of the drink to Europe in 2017.[468] In 2019, Drake began collaborating with Hocking on Mod Sélection, a luxury range of champagne,[469] and in May 2021, formed part of a $40 million series B investment funding round led by D1 Capital Partners in Daring Foods Inc., a vegan meat analogue corporation.[470] That September, he purchased a minority stake in Californian food chain Dave's Hot Chicken,[471] and organized a promotion on October 24, 2022, to give away free chicken to Toronto residents on his 36th birthday.[472]

Fashion

In December 2013, Drake announced he was signing with Nike and Air Jordan, saying "growing up, I'm sure we all idolized Michael Jordan. I [am] officially inducted into the Team Jordan family."[473] Drake also released his own collection of Air Jordans, dubbed the "Air Jordan OVOs".[474] This foresaw collaborations between OVO and Canada Goose,[475] in which various items of clothing were produced.[476] In 2020, A Bathing Ape announced a collaboration with Drake, releasing an OVO x BAPE collection of clothing,[477] while he also partnered with candle manufacturer Revolve to create "Better World Fragrance", a line of scented candles.[478][479]

In December 2020, Drake announced Nocta, a sub-label with Nike. In a press release, Drake said "I always felt like there was an opportunity for Nike to embrace an entertainer the same way [as] athletes," he wrote, "to be associated with the highest level possible was always my goal."[480] The apparel line is named after Drake's "nocturnal creative process", in which Nike described as a "collection for the collective", and noted by GQ as "fashion-forward, minimal-inspired sportswear".[481] One clothing item features an image of Drake's muses, Elizabeth and Victoria Lejonhjärta, with a poem.[482] After the first collection sold out, another was released in February 2021, which introduced t-shirts, adjustable caps, a utility vest, and a lightweight jacket.[483] That July, OVO released the "Weekender Collection", which includes a line of hoodies, velour sweatsuits, t-shirts, shorts, and accessories for women.[484] OVO then released a "Winter Survival Collection" that December which included puffer jackets, vests, and parkas made with 700-fill down and Oeko-Tex certified down feathers.[485] They followed this with limited Jurassic Park-themed collection and an indoor footwear collaboration with Suicoke,[486] as well as a Playboy-collaborated capsule collection.[487]

In July 2022, a capsule inspired by and in collaboration with Mike Tyson was released, featuring both blouson jackets and caps.[488] In conjunction with Spotify's 12-year, $540 million sponsorship deal with FC Barcelona, the club wore special edition OVO owl silhouette branded jerseys in their El Clásico match against Real Madrid CF on October 16, 2022.[489] OVO then partnered with former professional ice hockey player Tie Domi and fashion retailer Roots Canada to release a capsule collection on October 28, matching Domi's jersey number for the New York Rangers and Toronto Maple Leafs;[490] a capsule collection was later released in collaboration with the Maple Leafs in November.[491]

Personal life

Health and residences

Drake lives in Toronto, Ontario, in a 35,000-square-foot, $100 million estate nicknamed "The Embassy",[492] which was built from the ground-up in 2017[493][494] and is seen in the video to his song "Toosie Slide".[495][496] He owned a home nicknamed the "YOLO Estate" in Hidden Hills, California, from 2012 to 2022,[497] and bought a Beverly Crest home in 2022 from Robbie Williams for $70 million.[498] He owns a condominium adjacent to the CN Tower.[499] He also owns a Boeing 767,[500][501] and in 2021, rented a $65 million multi-purpose property in Beverly Hills.[502][503][504]

Drake has a variety of tattoos, some of which are symbols associated with personal accomplishments, such as a jack-o-lantern, "October Lejonhjärta" (transl. October Lionheart), owls, and a controversial Abbey Road (1969) inspired depiction of himself and the Beatles.[505][506] He has portraits of Lil Wayne, Sade, Aaliyah, Jesús Malverde, Denzel Washington, 40, his parents, grandmother, maternal uncle, and son; and several related to Toronto, including the CN Tower and the number "416".[507]

On August 18, 2021, Drake revealed he contracted COVID-19 amidst the pandemic, which led to temporary hair loss. He was also one of the first celebrities to publicly test for the virus in March 2020.[508] He contracted the disease again in 2022, causing the postponement of reunion concerts with Lil Wayne and Nicki Minaj.[509]

Family and relationships

Drake's paternal uncles are musicians Larry Graham and Teenie Hodges.[510] Larry Graham was a member of Sly and the Family Stone,[511] while Hodges contributed to songs for Al Green, including "Love and Happiness", "Here I Am (Come and Take Me)", and "Take Me to the River".[512][513]

He dated SZA between 2008 and 2009,[514] and was in an on-again, off-again relationship with Rihanna from 2009 to 2016.[515] He has mentioned the relationship in every one of his studio albums,[516] and when presenting Rihanna with the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award in 2016, he said "she's a woman I've been in love with since I was 22 years old."[517] On his relationship with her, he said on the talk show The Shop:

As life takes shape and teaches you your own lessons, I end up in this situation where I don't have the fairy tale [of] 'Drake started a family with Rihanna, [it's] so perfect.' It looks so good on paper [and] I wanted it too at one time.[518]

Drake is a father to a son named Adonis, who was born on October 11, 2017, to French painter and former model Sophie Brussaux.[519][520][521] Brussaux's pregnancy was the subject of several rumours after featuring in a TMZ article in early 2017.[522] After the nature of the pair's relationship was discussed in Pusha T's "The Story of Adidon", Drake confirmed his fatherhood on the album Scorpion in 2018.[520][523]

Discography

Solo studio albums

- Thank Me Later (2010)

- Take Care (2011)

- Nothing Was the Same (2013)

- Views (2016)

- Scorpion (2018)

- Certified Lover Boy (2021)

- Honestly, Nevermind (2022)

- For All the Dogs (2023)

Collaborative studio albums

Tours

Headlining

- Away from Home Tour (2010)

- Club Paradise Tour (2012)

- Would You Like a Tour? (2013–2015)

- Boy Meets World Tour (2017)

- Assassination Vacation Tour (2019)

- Anita Max Win Tour (2025)

Co-headlining

- America's Most Wanted Tour (with Young Money) (2009)

- Drake vs. Lil Wayne (with Lil Wayne) (2014)

- Summer Sixteen Tour (with Future) (2016)

- Aubrey & the Three Migos Tour (with Migos) (2018)

- It's All a Blur Tour (with 21 Savage & J. Cole) (2023–2024)

Filmography

Film

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Charlie Bartlett | A/V Jones | Minor role |

| 2008 | Mookie's Law | Chet Walters | Short film |

| 2011 | Breakaway[524] | Himself | Cameo |

| 2012 | Ice Age: Continental Drift | Ethan | Voice role |

| 2013 | Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues | Ron Burgundy fan | Cameo |

| 2014 | Think Like a Man Too | Himself | |

| 2017 | 6ix Rising[525] | Noisey documentary | |

| The Carter Effect | Documentary, also executive producer | ||

| 2019 | Remember Me, Toronto | Documentary by Mustafa the Poet[526] | |

| 2022 | Black Ice[527] | None | Documentary, executive producer |

| 2023 | For Khadija[528] | None |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Blue Murder | Joey Tamarin | Episode: "Out-of-Towners: Part 1" |

| 2001–2008 | Degrassi: The Next Generation | James "Jimmy" Brooks | Main role; 100 episodes |

| 2002 | Soul Food | Fredrick | Episode: "From Dreams to Nightmares" |

| Conviction | Teen Fish | Television film | |

| 2005 | Best Friend's Date | Dater | Episode: "Season Finale" |

| Instant Star | Himself | Episode: "Personality Crisis" | |

| 2008 | The Border | PFC Gordon Harvey | Episode: "Stop Loss" |

| 2009 | Being Erica | Ken | Episode: "What I Am Is What I Am" |

| Sophie | Ken | Episode: "An Outing with Sophie" | |

| Beyond the Break | Himself | Episode: "One 'Elle' of a Party" | |

| 2010 | When I Was 17 | Episode: "Drake, Jennie Finch & Queen Latifah" | |

| Drake: Better Than Good Enough | Himself | MTV documentary | |

| 2011 | Juno Awards | Host | Television special |

| Saturday Night Live | Himself (musical guest) | Episode: "Anna Faris/Drake" | |

| 2012 | Punk'd | Himself | Episode: "Drake/Kim Kardashian" |

| 2014, 2016 | Saturday Night Live | Himself (host/musical guest) | Episode: "Drake" |

| 2018 | The Shop | Himself | Episode 2 |

| The Egos | Episode: "OMP: Drake" | ||

| 2019– | Euphoria | None | Executive producer |

| 2019–2023 | Top Boy | None | |

| 2021–2022 | Chillin' Island | None | |

| 2023 | Saint X[529] | None |

See also

- Culture of Toronto

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

- List of Canadian musicians

- List of people from Toronto

- List of artists who reached number one on the UK Singles Chart

- List of highest-certified music artists in the United States

- List of best-selling music artists

- List of Billboard Hot 100 chart achievements and milestones

- List of most-followed Instagram accounts

- List of Canadian hip hop musicians

- List of Canadian Jews

- List of Black Canadians

- Black Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area

- History of the Jews in Toronto

- List of artists who reached number one on the Canadian Hot 100

- List of Canadian Grammy Award winners and nominees

- List of most-streamed artists on Spotify

Notes

- ^ "Taylor Made Freestyle" was removed from social media after Tupac Shakur's estate threatened civil action against Drake for including AI-generated vocals of Shakur on the song.[9]

- ^ This excludes his appearance on the number-one single "Sicko Mode" for which he did not receive official credit.

References

- ^ "11 Times Drake Channeled His 'Champagne Papi' Alter-Ego: From 'The Motto' to 'Mia'". Billboard. October 12, 2018. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "The Drake Look Book". GQ. October 2016. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2019.