Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union

This article contains promotional content. (January 2022) |

Oromia Coffee Farmers' Cooperative Union | |

| Founded | 1 June 1999 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia |

| Location |

|

Key people |

|

| Affiliations |

|

| Website | https://www.oromiacoffeeunion.org/ |

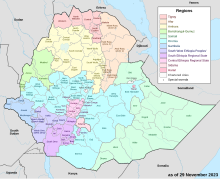

The Oromia Coffee Farmers’ Cooperative Union (OCFCU) is a smallholder farmer-owned cooperative union based in the Oromia region of Ethiopia. The aforementioned region is characterized by its unique native vegetation and tropical climate conducive to coffee bean growth.[1] OCFCU is a democratic, member-owned business operating under the principles of the International Cooperative Alliance and Fair trade,[2] and the Union plays a central role in the Ethiopian coffee marketing chain.[3] The members of OCFCU grow, process, and supply organic Arabica coffee for export.[1]

History and development

[edit]

Though the Oromia region was the area where coffee was first discovered,[1][2][3] the previous socialist Derg regime imposed collective ownership, and farmers were required to channel all sales through local traders and auction centers in Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa,[3] thereby stunting the growth of the coffee trade in the region. Importantly, farmers had little autonomy over sales and exports and therefore were impoverished.[2] In the 1990s, the OCFCU’s first General Manager, Tadesse Meskela, spent two months in Japan as a trainee in cooperative initiatives.[2] He returned to post-socialist Ethiopia with informative DVDs on Japanese cooperatives and cooperative principles.[2] These DVDs were shown to the Oromia agricultural bureau management, and Meskela's idea for a market-oriented democratic organisation was accepted and implemented.[2] The OCFCU was established on 1 June 1999 by thirty-four cooperatives representing approximately twenty-two thousand members with US$90,000 in capital.[4] Soon, Oromia became the capital of coffee for the nation, holding more than 65% of the lands designated for coffee growth. The Union started by training farmers, agricultural staff, cooperative promoters, and government officials in cooperative principles for eight months.[2] Initial exports amounted to seventy-two metric tonnes and sales of US$130,000.[4] As of 2020, the OCFCU had 405 cooperatives representing over four hundred thousand members with capital exceeding US$20 million.[4][5] Furthermore, exports had grown to seven thousand metric tonnes with sales exceeding $40 million.[2] Previously, the Union would facilitate the exchange between farmers and local coffee roasters who would purchase raw coffee beans.[6] In July 2018, OCFCU invested the equivalent of more than USD$1.5 million to build its first coffee roasting and packaging complex at Gelan Town in Oromia Regional State.[5] The plant was completed and started production in February 2020 with the aim to roast, grind, and package the coffee for local use.[5]

Vision, mission, and objectives

[edit]

The OCFCU states their vision for the Union is that they "aspire to see cooperative societies who strongly emerge as the engine of development in rural and urban settings to achieve transformation."[7]

Guided by the principles of the International Cooperative Alliance, the primary mission of the Union is to reduce transaction costs through the facilitation of direct sales of coffee.[8] The direct sale/export of coffee sees the by-passing of auctions and elimination of intermediaries sales through vendors such as coffee collectors, suppliers, and exporters; thereby, deriving greater profit which is given back to farmers through dividends.[8] This has the subsequent aim of trying to solve the problem of delay in payment from the exporters.[8]

Furthermore, the Union has six focus objectives:

- Improving farmers’ incomes by exporting their coffee directly.[9]

- Improving the quality and productivity of Ethiopian coffee.[9]

- Improving the quality of services to member farmers and clients.[9]

- Improving the social conditions of farmers.[2][9]

- Improving the sustainability of the local coffee industry.[9]

- Regulate and stabilize the local market.[9]

Management structure

[edit]The Union has five key managers: General Manager, Deputy General Manager, Commercial Department Head, Financial Department Head, and Export Sales Head,[10] as well as a general assembly consisting of one representative chairperson from each of the 405 cooperatives.[2] The annual general assembly meetings include top management and the representative chairperson from each cooperative.[2] This is where the definition and evaluation of Union strategies take place.[2] Policies and strategies approved at the annual general meetings are subsequently given to the Cooperative’s Boards for execution; and then, the board delegates to management to undertake day-to-day activities.[2] Cooperative management is answerable to their respective board of directors and the cooperative members, the vast majority of which are indigenous small landholders located in the Oromia region.[2]

Types of coffee

[edit]

The OCFCU distributes six organic Arabica coffee beans.[4] Oromia offers natural (un-washed) and washed coffee beans. These coffee beans come from six areas of Oromia:

- Harar: Natural coffee. Medium to light acidity, full-body, and strong mocha flavor with blueberry notes.[11]

- Jimma: Natural coffee. A well-balanced cup, medium acidity, and body with distinct winy flavor.[12]

- Limmu: Washed coffee. A well-balanced cup, medium acidity, and body with distinct winy flavor.[13]

- Nekemte: Natural and washed coffee. Good acidity, medium body with a wild fruity finish.[14][15]

- Sidamo: Natural and washed coffee. Bright acidity, medium body with spicy and citrus flavors..[16][17]

- Yirgacheffe: Natural and washed coffee. Bright acidity, medium body marked jasmine and lemon flavors.[18][19]

Success factors and benefits to members

[edit]Exports

[edit]In conjunction with their mission and objectives, the OCFCU realized the importance of the export market and started building a direct connection between small landholders growing coffee and international coffee markets.[2] As of 2014, export destinations include Australia, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and more.[2] As of 2014, the Union was Ethiopia’s largest exporter of organic coffee and the second largest in Fair trade coffee exports in the world.[2]

Transaction cost reduction and dividends

[edit]Since the coffee market is saturated with more sellers (farmers) than buyers, buyers hold considerable power in trade and price determination.[20] Consequently, cooperatives have been considered as organisations playing significant socioeconomic roles by reducing transaction costs and increasing the bargaining power of suppliers.[21] The Union has been able to reduce the number of intermediaries between coffee growers and the export market, significantly increasing the share of the value-added chain. The Union has subsequently increased the bargaining power of farmers and reaped economies of scale by becoming large, and economies of scope by offering different coffee varieties.[2] Furthermore, cooperatives improve poverty in developing countries and allow the possibility for income generation from employment opportunities.[22] In accordance with their objective of improving farmers’ incomes, the Union disburses seventy percent of profits to cooperatives and their members through dividends.[2] As of 2014, $3 million in dividends had been paid to farmers.[2] Through their successes, the Union is now able to employ two thousand seasonal and permanent employees.[2]

Awards and certifications

[edit]The Union has received several awards and has been recognized as a preeminent Arabica coffee bean producer. In 2000, OCFCU samples were rated as among the best in the world by roasting houses at the Speciality Coffee Association of America conference.[2] At the 2012 Coffee of the Year Competition, OCFCU coffee was ranked first out of 250 different coffees.[2] Furthermore, the OCFCU has numerous certifications including Fair trade, organic, UTZ, and Rainforest Alliance certified coffees.[1] The 405 cooperatives within OCFCU operate under the Fair trade principles. In 2002, the first cooperative was certified Fair trade, and as of 2020, forty-eight cooperatives are Fair trade certified.[2][23]

Local economic and social development

[edit]

As well as economic development, the Union has brought significant social benefits to members and local stakeholders; these include improved infrastructure and services through building roads, storage facilities, bridges, clinics, and schools in the local communities.[2] OCFCU also offers access to banking and credit services, coffee quality control training, education, flour mills, and community clinics, among others for members.[2] The following table from the OCFCU website outlays the Union's economic and social endeavors:[24]

| Sectors | Name of Project | Number of Projects Accomplished | Number of Beneficiaries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Primary School | 26 | 15,660 |

| School Expansion | 35 | 6,140 | |

| Kindergarten | 3 | 884 | |

| Library and Laboratory | 3 | 586 | |

| Staff Office | 3 | 47 | |

| Teachers’ Residence | 2 | 22 | |

| Health | Health Post | 10 | 72,000 |

| Occupied Medical Equipment | 3 | 21,000 | |

| Clinic Maintenance | 1 | ||

| Dry Latrine | 7 | 4,250 | |

| Water Development | Spring Development | 86 | 18,432 |

| Bore Hole | 3 | 22,680 | |

| Transportation | Road | 5 | 27,000 |

| Bridge | 9 | 21,000 | |

| Office Construction | Office | 7 | 23 |

| Coffee Processing Mills | 48 | 2,580 | |

| Agro-industry | Flour mills | 5 | 5,000 |

| Warehouse | Store | 1 | 780 |

Issues and challenges

[edit]Agronomy and sustainability

[edit]Coffee crops are significantly affected by climate volatility. As diseases and pests become more prevalent and temperatures rise and patterns of rainfall become more volatile, it becomes significantly more difficult to grow coffee successfully.[2] The size of land held by farming families is heterogeneous and some communities are more vulnerable than others to climate volatility.[2] Sustainable farming has been a staple of Ethiopian coffee farming for generations, and most coffee is grown under shade and is bird-friendly.[2] In 2014, OCFCU partnered with a roasting house in the Netherlands with the aim to eliminate the reliance on wood for household use and produce carbon-neutral coffee from farm to cup.[2] According to the plan, farmers are incentivised to participate in the scheme with bonus payments of USD$25 and cooking stoves are being distributed to families so that they will stop using wood for their cooking needs.[2] The reduction of carbon dioxide with the new stoves compared to cooking over an open fire is up to 70%, and it is estimated that the project will generate over 30,000 carbon credits.[2] The Fair trade premium from the carbon credits goes toward projects which will make communities better equipped to deal with the effects of climate volatility.[2]

Another concern for OCFCU farmers is the aging of coffee trees. The coffee tree can take up to five years to mature, and thus, intensive labor is needed to bring the tree to maturation and reap profits from proper tree development.[20] Furthermore, when the crop is no longer profitable, it is difficult to clear the land to plant a new crop to recover any losses.[20][25] Previously, agronomic development was stimulated by investment in local tree plantations in conjunction with the European Union. This partnership ended in the 1980s, and there has been insufficient investment in agronomic development since.[2]

Price volatility

[edit]A systemic risk faced by farmers is coffee price volatility. Coffee is the most accessible source of income for poor smallholder Ethiopian farmers.[26] However, coffee prices, being a commodity, are inherently more volatile than industrial products.[3] Since Ethiopian farmers are price takers, changes in the world production and prices of coffee directly and significantly affect Ethiopian coffee prices, and thus, farmers' profits.[26] Moreover, when coffee prices are low, many farmers suffer from inadequate income, and thus, hunger.[2][27] Previously, in the lean period preceding harvest (June to September), farmers would borrow at high interest rates from private lenders to subsist and improve their farming practices and harvests.[2] However, in 2005, the Union implemented its own financial services through the Cooperative Bank of Oromia.[2] The organisation provides pre-harvest financing and loan advances to 70% of members to ensure crop development.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "OCFCU – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Meskela, Tadesse; Teshome, Yalem (2014). "From Economic Vulnerability to Sustainable Livelihoods: The Case of Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union in Ethiopia" (PDF). SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2400132. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 154761140.

- ^ a b c d Gemech, Firdu. (2005). Coffee price volatility in Ethiopa : effects of market reform programmes. University of Paisley. OCLC 226214522.

- ^ a b c d "About US – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ a b c Samuel, Gelila (2019-12-31). "Ethiopia: Farmers Union Plants Coffee Complex in Gelan". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ Holden, Matt (2015-03-10). "Visiting Ethiopia, the birthplace of coffee". Good Food. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Vision – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ a b c "Mission – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e f "Objective – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Contact Us – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Harar Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Jimma Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Limu Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Nekemte Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Nekemte Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Sidamo Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Sidamo Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Yirgacheffe – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Yirgacheffee Coffee – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ a b c Wright, Jessica; Zeltmann, Steve; Griffin, Ken (2017). "Coffee Shops and Cash Crops: Gritty Origins of the World's Favorite Beverage". Competition Forum. 15 (1): 102–112 – via ProQuest Central.

- ^ Mojo, Dagne; Fischer, Christian; Degefa, Terefe (2017). "The determinants and economic impacts of membership in coffee farmer cooperatives: recent evidence from rural Ethiopia". Journal of Rural Studies. 50: 84–94. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.12.010. ISSN 0743-0167. S2CID 53481667.

- ^ GETNET, Kindie; ANULLO, Tsegaye (2012-04-24). "Agricultural Cooperatives and Rural Livelihoods: Evidence from Ethiopia". Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics. 83 (2): 181–198. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8292.2012.00460.x. hdl:10.1111/j.1467-8292.2012.00460.x. ISSN 1370-4788. S2CID 155043862.

- ^ "Oromia Coffee Farmers' Cooperative Union (Ethiopia)". Fairtrade International. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ "Life Improvement – Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union". Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark, author. (9 July 2019). Uncommon grounds : the history of coffee and how it transformed our world. ISBN 978-1-5416-9938-0. OCLC 1132203670.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Worako, T.K.; Jordaan, H.; van Schalkwyk, H.D. (September 2011). "Investigating Volatility in Coffee Prices Along the Ethiopian Coffee Value Chain". Agrekon. 50 (3): 90–108. doi:10.1080/03031853.2011.617865. ISSN 0303-1853. S2CID 154561683.

- ^ Bastin, Anne; Matteucci, Nicola (2007). "Financing Coffee Farmers in Ethiopia: Challenges and Opportunities". Savings and Development. 31 (3): 251–282. ISSN 0393-4551. JSTOR 41406454.