Ollagüe

| Ollagüe | |

|---|---|

Ollagüe as viewed from the west. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,868 m (19,252 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 1,686 m (5,531 ft) |

| Listing | Ultra |

| Coordinates | 21°17′S 68°11′W / 21.283°S 68.183°W[2] |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Ullawi (Aymara) |

| Geography | |

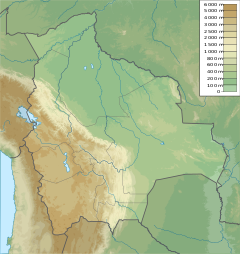

| Location | Potosí Department, Nor Lípez Province, Pelcoya Canton, Bolivia - Antofagasta Region, El Loa Province, Chile |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | Pleistocene |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | 65,000 years ago[3] |

Ollagüe (Spanish pronunciation: [oˈʎaɣwe]) or Ullawi (Aymara: [uˈʎawi]) is a massive andesite stratovolcano in the Andes on the Bolivia–Chile border, within the Antofagasta Region of Chile and the Potosi Department of Bolivia. Part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, its highest summit is 5,868 metres (19,252 ft) above sea level and features a summit crater that opens to the south. The western rim of the summit crater is formed by a compound of lava domes, the youngest of which features a vigorous fumarole that is visible from afar.

Ollagüe is mostly of Pleistocene age. It started developing more than one million years ago, forming the so-called Vinta Loma and Santa Rosa series mostly of andesitic lava flows. A fault bisects the edifice and two large landslides occurred in relation to it. Later two groups of dacitic lava domes formed, Ch'aska Urqu on the southeastern slope and La Celosa on the northwestern. Another centre named La Poruñita formed at that time on the western foot of the volcano, but it is not clear whether it is part of the main Ollagüe system. Activity at the summit continued during this time, forming the El Azufre sequence.

This phase of edifice growth was interrupted by a major collapse of the western flank of Ollagüe. Debris from the collapse spread in the form of hummocks down the western slope and into an adjacent salt pan, splitting it in two. The occurrence of this collapse was perhaps facilitated by a major crustal lineament that crosses Ollagüe from southeast to northwest. Later volcanic activity filled up the collapse scar, forming the Santa Cecilia series. This series includes lava flows as well as a compound lava dome on the western rim of the summit crater, which represent the youngest volcanic activity of Ollagüe. While there is no clear evidence of historical eruptions at Ollagüe, the volcano is considered to be potentially active and is monitored by the National Geology and Mining Service (SERNAGEOMIN) of Chile. Hydrothermal alteration has formed sulfur deposits on the volcano, which is the site of several sulfur mines. Later glaciations have formed moraines on the volcano.

Name

[edit]The original Aymara name of the volcano was Ullawi. It is derived from Aymara ullaña to see, to look at, to watch, and wi which is a nominalizing suffix to indicate a place, thus "viewpoint".[4]

The common name is Ollagüe.[a] Other alternate names are Oyague, Ollagua and Oyahué.[1]

Geography and geomorphology

[edit]Ollagüe straddles the border between Chile and Bolivia, with most of the edifice lying on the Bolivian side.[9] The Chilean portion lies in the commune of Ollague, in the El Loa province of the Antofagasta Region,[10] while the Bolivian segment lies in the Potosi department.[11] Towns and human sites close to Ollagüe are Amincha,[10] Buenaventura,[12] Cosca, El Chaco, Ollague[13] and Santa Rosa,[14] and the main road of Ollagüe runs along the western foot of the volcano.[12] The first documented ascent was in 1888.[15] The mountain reportedly can be climbed from the eastern side.[16] The occurrence of warning signs about minefields has been reported.[17]

Regional

[edit]Ollagüe is part of the Central Volcanic Zone (CVZ),[18] one of the volcanic arcs that exist in the Andes. The Andes have segments with volcanic activity and segments without; volcanic activity occurs only where the angle of subduction is relatively steep. There are four such segments, the Northern Volcanic Zone, the CVZ, the Southern Volcanic Zone and the Austral Volcanic Zone. The subducted part of the plate (slab[19]) loses water as it sinks into the mantle, and this water and other components migrate into the mantle that lies between the subducted plate and the overlying crust (mantle wedge[19]) and cause the formation of melts in the wedge.[20]

The CVZ is located between 16° and 28° southern latitude, on the western margin of South America.[18] At this latitude, 240–300 kilometres (150–190 mi) west of the CVZ,[21] the oceanic Nazca Plate subducts steeply beneath the continental South America Plate in the Peru–Chile Trench.[22][23] East of the CVZ lies the Altiplano, a plateau with average elevations of 3,800 metres (12,500 ft).[21] The CVZ contains about 1,100 volcanoes of Cenozoic age, including Parinacota, San Pedro and Tata Sabaya. Many volcanoes in the CVZ have summit heights exceeding 5,500 metres (18,000 ft),[18] forming the Occidental Cordillera of the Andes at these latitudes.[24] About 34 of these volcanoes are considered to be active;[25] most of the volcanoes have not received detailed scientific reconnaissance.[26] A notable feature of the volcanoes of the CVZ is that they formed over a fairly thick crust, which reaches a thickness of 70 kilometres (43 mi);[24] as a consequence contamination with crustal material has heavily affected the magmas that formed the volcanoes. The crust is not uniform along the length of the south-central CVZ because the northern segment is of Proterozoic and the southern of Paleozoic age.[27]

The Central Andes formed first during the Paleozoic–Eocene and were worn down by erosion during the Oligocene. The recent volcanic activity started during the Miocene and includes major ignimbrite eruptions of dacitic to rhyolitic composition; such large eruptions began 23 million years ago and caused the formation of calderas like Galán. The total volume of this formation exceeds 10,000 cubic kilometres (2,400 cu mi). Stratovolcanoes also began to form 23 million years ago, although most were constructed in the last 6 million years. They are volumetrically much smaller and were formed by magmas whose composition ranges from basaltic andesite to dacite. Finally, small alkaline volcanic centres are found primarily in the back-arc region and appear to be young.[24] A notable trait of the Central Andes are the long strike-slip faults that extend from the Eastern Cordillera northwest through the Altiplano into the volcanic arc. These include from north to south the Pastos Grandes–Lipez–Coranzuli, Calama–Olacapato–El Toro, Archibarca–Cerro Galan and Chulumpaja–Cerro Negro lineaments. Monogenetic[b] centres are aligned on these faults.[21]

Local

[edit]Ollagüe is a stratovolcano and lies isolated slightly east of the main volcanic arc.[2] The volcano is usually covered with snow, which together with yellow and red colours gives Ollagüe a "beautiful" appearance.[16] Other than some past glacial activity, the arid climate of the Altiplano region has kept erosion rates low, meaning that the volcanic edifice is well preserved.[30] On the other hand, lack of erosion also means that relatively little of its internal structure is exposed.[31]

Ollagüe has two summits, Ollagüe South is 5,868 metres (19,252 ft) high and Ollagüe North 5,863 metres (19,236 ft).[32] Southwest of the summit is the[33] summit crater 300 metres (1,000 ft) below the summit[16] with a narrow opening towards the south, which forms the Quebrada El Azufre. The rim of the crater culminates into 5,868 metres (19,252 ft) high Ollagüe South. The western rim is formed by several lava domes.[14] These lava domes feature landslide deposits and lava flows that emanate from the foot of the dome. Originally they were considered to be a single lava dome,[34] before it was found that the dome is formed by four individual domes.[35] Just north of the summit crater lies another semicircular crater rim which encircles the summit crater on its northern side and whose high point is 5,863 metres (19,236 ft) high Ollagüe North.[14] The northeastern part of the edifice is old and affected by glaciation and the development of gullies, while the southwestern part has experienced younger activity and flank collapses.[36] The volume of the well exposed edifice is about 85 to 91 cubic kilometres (20 to 22 cu mi)[2] covering a surface area of 260 square kilometres (100 sq mi).[10] Ollagüe rises about 2,065 metres (6,775 ft) above the surrounding terrain.[30]

-

Ollagüe summit from Bolivia

-

View from the summit of Ollagüe to southwest

The volcano has a number of adventive vents on its slopes, especially the northwestern and southeastern slope. These include Ch'aska Urqu on the southeastern slope and La Celosa (4,320 metres (14,170 ft); also known as El Ingenio[1]) on the northwestern.[9] They lie at distances of 4–8 kilometres (2.5–5.0 mi) and 1–4 kilometres (0.62–2.49 mi) from the summit vent, respectively.[23] The alignment of these subsidiary vents with the summit vents suggests that a N55°W striking lineament influenced their eruption; such channelling of magma along radial fractures has also been observed on other volcanoes such as Medicine Lake volcano, Mount Mazama and South Sister.[37] A normal fault runs across the main edifice but is not aligned with these adventive vents,[21] and the Pastos Grandes-Lipez-Coranzuli lineament intersects with the volcanic arc at Ollagüe.[38] Fault scarps are found on the northwestern and southeastern side of the edifice.[39] Overall, northwest trending lineaments exercised a strong influence on the tectonic development of Ollagüe,[40] and may be the path that feeder dykes of the more recent eruptions followed.[41] The basement undergoes extension perpendicularly to the lineament.[42]

A 700 metres (2,300 ft) wide[43] phreatomagmatic vent named La Poruñita lies on the western slope, on the deposit formed by the sector collapse.[34] It lies at an elevation of 3,868 metres (12,690 ft),[1] is constructed out of tephra and formed on the sector collapse deposit.[34] Farther up on the edifice, two cinder cones are found just north and west of the highest summit of Ollagüe.[14]

Older volcanic centres around Ollagüe are Cerro Chijliapichina southwest (also known as Cerro Peineta[36]), Cerro Canchajapichina south and Wanaku east of the volcano. These centres are unrelated to Ollagüe and were deeply affected by glaciation.[30] On the eastern foot the Carcote ignimbrite crops out,[9] a 5.9–5.5 million years old ignimbrite that is part of the Altiplano–Puna volcanic complex. These ignimbrites form the basement in much of the region.[2] The Carcote ignimbrite originally formed a plateau that extended around the volcano.[44] Off the western foot of Ollagüe lies a smaller volcanic centre that forms an effusive shield.[27]

The Salar de Ollague is located due north, while the Salar de San Martin lies southwest and Salar de Chiguana northeast of Ollagüe.[9] They are situated at elevations of 3,690–3,694 metres (12,106–12,119 ft).[32] The Salar de San Martin and the Salar de Ascotán farther south form a northwest–southeast trending graben delimited by the same normal fault that crosses the edifice of Ollagüe.[36] A ring plain formed by debris shed from Ollagüe surrounds the volcano.[45]

Glaciation

[edit]Presently, high insolation and evaporation as well as the dry climate prevent the formation of glaciers or the existence of a snow cover.[46][47] Ollagüe lies in one of the driest regions of South America.[46] Thus, the present-day snowline is higher than the volcano.[48] Underground ice deposits have been found on Ollagüe; presumably they form through evaporation cooling.[49]

Ollagüe has experienced glacial activity. Moraines are found on top of young lava flows and glacial valleys cut into the slopes.[50] On the western side, there are remnants of a moraine girdle,[51] which reaches an elevation of 4,500 metres (14,800 ft) on the southwestern foot of the volcano.[52] Another possibly separate moraine girdle has been reported in the summit region, at elevations of about 5,000 metres (16,000 ft). This moraine is thought to have been formed during the Little Ice Age.[53] The Pleistocene snowline may have occurred at elevations of 5,000 metres (16,000 ft).[48] [33]

Debris avalanche

[edit]A major sector collapse occurred on the western flank of the edifice, with the deposit formed by the collapse extending west from it.[9] Debris from the collapse flowed for 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) into the Salar de San Martin[2]/Salar de Carcote, which slowed down the landslide.[54] Only the distal sector of the collapse deposit is still visible; the parts higher up on the edifice have been buried by more recent lava domes and lava flows.[55] The distal segment is also slightly raised compared to the more proximal parts.[56] The collapse deposit covers a surface area of 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi) and has a hummocky appearance, similar to the collapse deposit formed by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.[57] The avalanche deposit separates the Salar de San Martin from the Salar de Ollague.[1]

The younger debris avalanche deposit has a volume of about 1 cubic kilometre (0.24 cu mi). It was believed that it occurred about 600,000–400,000 years[38] or 800,000 ± 100,000 years ago,[43] but dating of the andesites cut by the collapse yielded a maximum age of 292,000 ± 25,000 years ago.[58] Later the deposit was covered by lake deposits and debris from the piedmont,[59] and evaporites accumulated in depressions within the deposit.[55] Several lake terraces are set into the avalanche deposit,[52] with the traces of the highstand of Lake Tauca being recognizable; thus the sector collapse predates the highstand.[60]

Andesitic lava bombs on top of the deposit may indicate that an eruption occurred during the collapse.[57] Indeed, pyroclastic materials have been found at the foot of the volcano within the collapse deposit, where they fill small depressions. These materials are formed by several units of pumice and ash, generated by fallout and lava dome collapses.[61]

The sector collapse was probably caused by the edifice oversteepening as it grew,[62] with Ollagüe reaching a critical height before the collapse.[63] Magma pressurization probably triggered the failure, as the remnants of a lava lake in its summit indicate that magma pressure in the edifice was high at the time of the collapse. Conversely, hydrothermal alteration – which tends to weaken the stability of a volcanic edifice – was not involved in the onset of instability.[64] The northwest–southeast cutting fault probably additionally destabilized the edifice, allowing it to fail into a southwestern direction.[65] A previous southwesterly tilt of the basement also assisted in focusing the failure into that direction.[66]

The sector collapse formed a 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) wide collapse scar on the upper western flank,[2] although the summit itself was probably unaffected.[57] This scar however was later filled by subsequent volcanic activity and modified by glaciation and is thus not conclusively identifiable.[2]

Two old sector collapses occurred during the older stages of volcanic activity. Their collapse scars are noticeable on the southeastern-southern and northwestern areas of the summit. The first is 400 metres (1,300 ft) high and 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) long, the second 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) long and many 10 metres (33 ft) high. Hydrothermally altered breccia with block sizes of several 0.1–1 metre (3.9 in – 3 ft 3.4 in) from the first collapse fills a valley on the western slope of the volcano.[39] Compared to the younger collapse, they are much narrower and have a highly unusual rectilinear form.[67] These collapses occurred about 450,000 years ago along the strike of a normal fault that cuts across Ollagüe.[41] Like in the young collapse, the summit was unaffected.[64] The lava domes that form the western rim of the summit crater have been subject to smaller sector collapses as well.[14]

-

Fumarole clearly visible

-

Panoramic image, with Ollagüe in the centre

Composition

[edit]Ollagüe has erupted rocks ranging from basaltic andesite to dacite.[18] Blobs of basaltic andesite are found in all rocks from the volcano;[50] they probably formed when mafic magma was quenched by colder felsic magma.[68] The andesites and dacites are relatively rich in crystals.[50] Phenocrysts in the main andesite-dacite series include amphibole, apatite, biotite, clinopyroxene, ilmenite, magnetite, orthopyroxene, plagioclase and rarely olivine, quartz and zircon. The more acidic rocks also contain rare sphene. Some of the phenocrysts are surrounded by reaction rims, [c] suggesting that they were not in chemical equilibrium with surrounding magma. Cumulates of phenocrysts indicate their formation during the magma differentiation process.[50]

Overall, the composition of Ollagüe's rocks fits into a high-potassium calc-alkaline series.[18] Gabbroic clots embedded in the lavas probably formed from cumulates.[68] Xenocrysts with large reaction rims[c] testify to a strong crustal contamination of the forming magma.[70]

Areas of hydrothermal alteration are found on Ollagüe, including in the summit crater, on its northeastern and northwestern rim and low on the northwestern slope.[14] Alunite, gypsum and sulfur were formed by the alteration on the summit and the northwestern slope,[39][11] and chalcedony, clay, kaolinite and opal are found as well.[11]

The overall magma temperatures ranged 825–1,000 °C (1,517–1,832 °F) for the andesitic and dacitic magmas and 1,010–1,060 °C (1,850–1,940 °F) in the basaltic andesite.[71] The magmas became cooler over time, with the post-collapse magmas being colder than the pre-collapse eruptive products.[72] Variations in temperature between the outside and the inside of phenocrysts suggest that the magma chamber of Ollagüe was occasionally reheated by fresh magmas.[71] Water contents of the main edifice magmas range 3-5% by weight; in the Ch'aska Urqu and La Celosa magmas the water content is less well determined,[73] but is comparable to that of the main edifice magmas.[74] Later research, however, has raised questions about the reliability of the method used to determine water content in magma, which may have been lower than 3–5%.[75]

Element compositions match those of other volcanoes in the CVZ.[18] Ollagüe magmas did not exclusively form from fractional crystallization; magma mixing and crustal contamination contributed to the formation of the magmas although it is not easy to determine what the composition of contaminants was.[76] Probably, it was in part hydrothermally altered upper crustal rock,[77] and in part Miocene age ignimbrites that crop out close to the volcano in Bolivia.[78] Crystal fractionation with some minor contamination by crustal components is probably the most satisfactory explanation for the magma chemistry of Ollagüe.[79] It is however difficult to tell the relative importance of contamination vs. assimilation.[80]

The composition data indicate that Ollagüe was underpinned by a large magma chamber that was the source of the main edifice building andesite magmas.[81] In this main magma chamber, differentiation processes generated the andesitic and dacitic magmas from basaltic andesite. The chamber itself was chemically zoned.[82] Episodically, new mafic magmas were injected into the magma chamber from below.[83] Subsidiary magma chambers which developed beneath the northwestern and southeastern flank gave rise to the La Celosa and Ch'aska Urqu volcanic centres, respectively. These subsidiary pathways also allowed basaltic andesite magmas to ascend to the surface; the main magma chamber would have intercepted any mafic magmas ascending into the central vent as such mafic magmas are denser.[81] The walls of the magma chamber were also affected by strong hydrothermal alteration processes, with weaker alteration also occurring in the walls of the subsidiary magma chambers.[84] La Poruñita was probably formed by magmas from the floor of the main magma chamber, or from the magma that enters the magma chamber from below; it had already undergone some crustal contamination in the depths of the crust when it erupted.[85]

Fumarolic activity

[edit]A major fumarole is active on the summit of the volcano, its plume reaching heights of 100 metres (330 ft).[51] It is strong enough that it can be seen on the ground from over 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away.[86] The vent of the fumarole lies in the summit lava domes,[51] more specifically in a 200 metres (660 ft) high and 350 metres (1,150 ft) wide collapse scar in the southeasternmost lava dome of the compound summit lava dome.[35] Other volcanoes in the area with fumarolic activity include San Pedro and Putana.[87]

Fumarole temperatures appear to be so low (less than 100 °C (212 °F)) that in 1989 the exhalations could not be detected in the Thematic Mapper infrared band of the Landsat satellite even during night.[88] More recent satellite observations have shown the existence of hotspots with temperature anomalies of about 5 K (9.0 °F);[89] the relatively poor visibility of the hotspots in satellite images contrasts with the good visibility of the fumarole from the ground and may reflect the relatively small surface area of the hotspots, which makes them difficult to isolate in satellite images.[86]

Fumarolic gases are made up primarily by SO

2 and H

2O; CO

2 is a subordinate component.[13] The amounts of SO

2 released have been measured; quantities vary but in December 2013 appeared to be about 150 ± 162 tonnes per day (1.74 ± 1.88 kg/s).[90]

Eruption history

[edit]Not many radiometric dates have been obtained on Ollagüe. Most dates are younger than one million years.[2] One proposed timeline subdivides the volcano into three stages: Ollagüe I between 1.2 million and 900,000 years ago, Ollagüe II 900,000–600,000 years ago and Ollagüe III 400,000 years ago to present.[38] La Poruñita, once considered of Holocene age,[1] has been dated at 680,000 ± 200,000 to 420,000 ± 200,000 years ago;[43] it is also not clear if it belongs to the Ollagüe volcanic system.[51] Magma output during the history of the volcano is about 0.09 cubic kilometres per millennium (0.0029 m3/s).[91]

Vinta Loma and Santa Rosa

[edit]The oldest stage of activity is known as Vinta Loma and formed the bulk of the volcanic edifice, especially on the eastern side and in the summit area.[92] During this stage, lava flows and some pyroclastic flows were erupted from a central vent.[2] The pyroclastic flows are exposed as a 60 metres (200 ft) thick sequence in a cirque close to the summit and reflect the occurrence of Plinian eruptions during this stage of volcanic activity.[93] The Vinta Loma series is subdivided into two groups separated by an unconformity, which are dated to 870,000 ± 80,000–641,000 ± 9,000 and 910,000 ± 170,000–1,230,000 ± 80,000 years ago respectively.[94] The Vinta Loma series more recently was partitioned into two series, Vinta Loma proper and the younger Santa Rosa.[39] Two summit crater rims and sector collapses formed during these stages.[94] The northern summit cinder/scoria cone and some lateral lava flows have been assigned to the Santa Rosa series.[39]

Lava flows from these stages have gray colours and rocky appearance which sometimes appears like it is covered by plates, with flow folds and some breccia. Their thicknesses and widths range 20–90 metres (66–295 ft), increasing on gentler slopes. Especially on the upper slopes, old colluvium conceals the surface of Vinta Loma lava flows.[92] The texture of the lavas ranges from porphyritic to seriate.[93] Two-pyroxene andesite is the dominant component but dacite has been found as well.[2]

The Vinta Loma edifice developed on top of an older fault. During the progression of volcanism the fault itself progressively propagated up and across the edifice and caused the southwest sector of the volcano to subside, without changes in volcanic activity. Eventually, the subsidence prevented lava flows of the Santa Rosa series from flowing northeast across the fault trace.[95] Then, the two older sector collapses occurred on the southwestern sides of the fault.[96]

Ch'aska Urqu, El Azufre and La Celosa series

[edit]Later the Ch'aska Urqu stage was erupted on top of Vinta Loma deposits[2] through radial vents on the southeastern flank. This stage is named after the 300 metres (980 ft) high Ch'aska Urqu lava dome on the southeastern flank.[93] The stage generated lava flows, lava domes and coulees[d] with compositions ranging from basaltic andesite to dacite, the former forming the base of the stage and the andesites and dacites being deposited above it.[2] These basaltic andesites form 1–2 metres (3 ft 3 in – 6 ft 7 in) thick grey coloured lava flows and a 20 metres (66 ft) thick plate-covered flow on top of the smaller ones.[98]

About 10 lava andesitic-dacitic domes and coulees were erupted on top of the basaltic andesite lava flows. They are short and have steep slopes, often ending with scree at the front. On the foot of the volcano they sometimes developed pressure ridges, and a 80 metres (260 ft) deep cleft in Ch'aska Urqu may have formed when the dome spread laterally during its formation.[98] As with Vinta Loma lavas,[92] the upper parts of the coulees are covered with thin colluvium.[98]

Simultaneously, another dacitic lava dome stage occurred on the northwestern flank, forming the La Celosa lava dome-coulee complex.[2] Its age has been controversial,[58] with it being first associated with the youngest post collapse stages through argon–argon dating;[51] then with the oldest stages of volcanic activity. Eventually potassium-argon dating yielded an age of 507,000 ± 14,000 years ago.[58] Two other dates obtained from northern lava domes are 450,000 ± 100,000 and 340,000 ± 150,000 years ago.[43] It has a lobate appearance, and similar to the Ch'aska Urqu dome a 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) wide rift cuts through the dome. The La Celosa complex was erupted from two separate vents, and owing to its low altitude it has not been affected by glaciation.[51]

The andesites and dacites are of grey to light grey colour respectively, with porphyritic to vitrophyric textures.[57] In this stage, dacites are more common than in the Vinta Loma deposits. Basaltic andesite contains olivine, while the dacites tend to contain more amphibole and biotite.[2] There is a tendency of silicic acid contents to increase in the upper parts of the exposure.[98]

Later evidence has indicated that some lava flows were erupted from the summit during the Ch'aska Urqu stage. Also, a structure interpreted as a former lava lake formed close to the summit during this time. The lava lake-like structure itself is undated; one of the lava flows was dated 410,000 ± 80,000 years ago and the southern summit cinder cone is 292,000 ± 25,000 years old. This series is known as El Azufre.[94] The El Azufre series was emplaced within a sector collapse, a collapse which generated pyroclastic deposits in the Poroto section of the southwestern flank.[95]

- Ollagüe from the town of the same name, the La Celosa lava domes are in the foreground

Post-collapse and Santa Cecilia series

[edit]The principal sector collapse occurred after the Ch'aska Urqu stage. It was followed by the eruption of andesitic lava flows and the compound lava dome in the summit region,[2] all focused into the collapse scar; this focusing is a phenomenon noted at other volcanoes which underwent flank collapses such as Planchón-Peteroa.[65] This formation has been named the Santa Cecilia series.[94] The compound summit lava dome probably fills the collapse scar but young lavas and glacial erosion make this assessment difficult.[51] Dates obtained on the summit lava domes range from 220,000 ± 50,000 years ago to 130,000 ± 40,000 years ago.[94] The youngest date was obtained on the youngest dome and shows an age of 65,000 years ago.[3] Tephras identified in the Salar Grande close to the Pacific coast and dated to be less than 330,000 years old may come from Ollagüe or Irruputuncu.[99]

The lava flows are best exposed on the western flank and have a grey colour. They display levees and pressure ridges and appear to be younger than the Ch'aska Urqu flows.[57] They originate at elevations of 4,800 metres (15,700 ft) and extend over distances of 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi).[35] The summit lava dome has a volume of 0.35 cubic kilometres (0.084 cu mi);[57] blocks with sizes of up to 10 metres (33 ft) were formed by landslides during its growth.[34] Later research has shown that the summit lava dome is actually formed by several separate lava domes that extend southeast along a feeder fissure and become younger to the southeast. The foot of the compound dome is formed by scree-like breccia deposits.[35]

Compositionally, the post-collapse magmas appear to fit into two distinct groups. Older flows are dominated by pyroxene with only small quantities of amphibole and biotite. Younger shorter flows farther up on the edifice and the summit lava dome conversely contain relatively large quantities of amphibole and biotite.[51]

Recent activity and hazards

[edit]The post-collapse lava flows have been affected by glacial activity, indicating that eruptive activity ceased before the end of the last glacial stage;[100] thus the volcano was largely constructed in pre-Holocene times.[53] However, a 300 metres (980 ft) long and 150 metres (490 ft) wide lava flow extending from the youngest summit lava dome appears to post-date glaciation, and the dome itself is also unmodified.[101]

An uncertain report of an eruption on 3 December 1903 exists,[1][102] as well as on 8 October 1927[13] when the population of Ollagüe fled for several days.[103] Increased fumarolic activity was observed in 1854, 1888, 1889, and 1960.[1] Substantial[104] earthquake activity occurs at Ollagüe in a diffuse pattern around the volcano, sometimes in the form of seismic swarms.[105]

The volcano is considered to be potentially active because of the fumarolic activity,[51] and SERNAGEOMIN publishes a volcano hazard index for Ollagüe.[10] A seismometer array was deployed in 2010–2011.[106] Future eruptions of Ollagüe may threaten the town of Ollague 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) away and the highway Route 21-CH.[13]

Sulfur mining and processing

[edit]Sulfur deposits on Ollague and neighbouring Aucanquilcha[107] and Olca[108] have been mined. On Ollague, the Santa Cecilia mine is on the northwestern rim of the crater and Santa Rosa mine in its centre.[14] In 1990, it was estimated that 3,000,000 tonnes (3,000,000 long tons; 3,300,000 short tons) of sulfur can be mined at the Santa Rosa mine.[11] According to a report in 1894, fumes released from sulfur beds on the volcano can incapacitate a man in seconds, making ascents difficult.[16]

Large-scale exploitation of natural resources in the area commenced in the late 19th century, when after the Saltpeter War Chile acquired the territories, began to exploit them[107] and capitalism and industrialization came to the region.[109] After initial efforts in 1899, 1902 and 1916, in 1932-1936 Luis Borlando set up a company[110] and began to mine sulfur on Ollagüe in response to demand by the saltpeter and copper industries.[111] The Chilean government had been encouraging mining development during the 1930s-1970s,[112] but only after the cessation of mining did it set up the infrastructure of the town of Ollague.[113] Mining was still underway in 1988[52] but ceased in the 1990s[111] as fluctuations in the global markets and the inability of the Chilean sulfur industry to compete on global markets forced its decline.[114]

A road reaching up to an altitude of 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) leads to the western and southern mines.[1] Sulfur was transported through an aerial tramway, which had replaced llamas.[115] A reduction plant with autoclaves is also found at Ollagüe,[11] it was the first such plant in Chile,[116] while south of the town a mining camp was set up at Buenaventura.[111] Worker camps with factory and residential buildings,[117] and railway stations of the Ferrocarril de Antofagasta a Bolivia railway between Bolivia and Chile, completed the infrastructure.[118][113]

Mining activity at Ollagüe is mostly documented by many technical reports and by local oral tradition.[118] Presently, much of the infrastructure is in ruins and is the backdrop of a past interplay between migration, modernization and economic activity.[119] Some of the sites were dismantled, others were left with virtually all their equipment.[120] Since 2015, an investigation project has been running in the town of Ollagüe to record and preserve the history of sulfur mining and industrialization in the region.[113]

Sulfur mining was mostly carried out by an indigenous workforce,[121] as other people are not adapted to the extreme conditions at high altitudes (cold, hypoxia, intense winds) and thus unable to perform the work.[122] One of the worker camps had a population of 85, according to a 1930 census.[123] The harsh climate and precarious social status of this workforce conditioned work at Ollagüe, where sulfur mining and processing occurred under unique conditions.[121] Contemporary references to working conditions are ambiguous, as there were both concerns about the working conditions in newspapers of the 1930s and the impact that working conditions could have on economic productivity.[124] There was a high turnover in the workforce, which came to a large degree from Bolivia[125] to the point that the Bolivian government curtailed it in 1925, triggering a decline in the Chilean sulfur industry.[126]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The ll in classical Spanish corresponds to the sound [ʎ] which matches the Aymara pronunciation (though today most Spanish speakers pronounce it [ʝ]).[5] The g in the name was inserted because using an intervocalic [w] consonant is foreign to classical Spanish[6] and the closest approximation is [ɣw] (gü). The rendering of the vowels as o and e rather than u and i derives from the fact that Andean languages (including Aymara) generally do not distinguish between the vowel sounds [o] and [u], as well as [e] and [i], so the precise sounds can vary by speaker.[7][8]

- ^ A monogenetic volcano is a volcano that has only one defined eruption event.[28] They often appear in groups.[29]

- ^ a b A reaction rim is a mineral phase that develops around a grain of another mineral, typically as a consequence of alterations of the grain-forming mineral.[69]

- ^ A coulee is a particular type of lava dome which has flowed sideward like a lava flow.[97]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Ollague". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1298.

- ^ a b Renzulli, Alberto; Tibaldi, Alessandro; Flude, Stephanie (August 2006). "NEW DATA OF SURFACE GEOLOGY, PETROLOGY AND Ar-Ar GEOCHRONOLOGY OF THE ALTIPLANO-PUNA VOLCANIC COMPLEX (NORTHERN CHILE) IN THE FRAMEWORK OF FUTURE GEOTHERMAL EXPLORATION" (PDF). 11th Chilean Geological Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 25, 2015.

- ^ Radio San Gabriel, "Instituto Radiofonico de Promoción Aymara" (IRPA) 1993, Republicado por Instituto de las Lenguas y Literaturas Andinas-Amazónicas (ILLLA-A) 2011, Transcripción del Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, P. Ludovico Bertonio 1612 (Spanish-Aymara-Aymara-Spanish dictionary)

- ^ Coloma, German (2011). "Valoración socioeconómica de los rasgos fonéticos dialectales de la lengua española". Lexis. 35 (1): 103. doi:10.18800/lexis.201101.003. S2CID 170911379.

- ^ Torck, Danièle; Wetzels, W. Leo, eds. (2006). Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2006. John Benjamins. p. 113. ISBN 9789027248190.

- ^ Coler, Matt (2014). A Grammar of Muylaq' Aymara: Aymara as spoken in Southern Peru. BRILL. p. 43. ISBN 9789004284005.

- ^ Cobo, Father Bernabe (1979). History of the Inca Empire: An Account of the Indians' Customs and Their Origin, Together with a Treatise on Inca Legends, History, and Social Institutions. University of Texas Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780292789807.

- ^ a b c d e Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1297.

- ^ a b c d "Volcán Ollagüe". SERNAGEOMIN (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Long, Keith R. (1990). "Volcan Ollague Mines". mrdata.usgs.gov.

- ^ a b Shea & Vries 2008, p. 666.

- ^ a b c d "Ollagüe". SERNAGEOMIN (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 140.

- ^ Brain, Yossi; Thurman, Paula (31 December 1998). Bolivia: A Climbing Guide. The Mountaineers Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-89886-495-3.

- ^ a b c d Pasley, Charles M. S. (1894-01-01). "Descriptive Notes on the Southern Plateau of Bolivia and the Sources of the River Pelaya". The Geographical Journal. 3 (2): 105–115. doi:10.2307/1774025. JSTOR 1774025.

- ^ Wörner, Gerhard (1 August 2018). "What's Your Next Dream?". Elements. 14 (4): 286. doi:10.2138/gselements.14.4.286. ISSN 1811-5209.

- ^ a b c d e f Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1296.

- ^ a b van Keken, Peter E (30 October 2003). "The structure and dynamics of the mantle wedge". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 215 (3–4): 325. Bibcode:2003E&PSL.215..323V. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00460-6. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Mattioli et al. 2006, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Gagnon, Katie; Chadwell, C. David; Norabuena, Edmundo (2005). "Measuring the onset of locking in the Peru–Chile trench with GPS and acoustic measurements". Nature. 434 (7030): 205–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..205G. doi:10.1038/nature03412. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15758997. S2CID 4416832.

oceanic Nazca plate and the continental South America plate

- ^ a b Feeley & Sharp 1995, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 223.

- ^ Tamburello et al. 2014, p. 4961.

- ^ Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 222.

- ^ a b Mattioli et al. 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Németh & Kereszturi 2015, p. 2133,21341.

- ^ Németh & Kereszturi 2015, p. 2131.

- ^ a b c Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 224.

- ^ Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 225.

- ^ a b Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 142.

- ^ a b Knoche 1932, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 230.

- ^ a b c d Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 234.

- ^ a b c Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 144.

- ^ a b c d e Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 148.

- ^ Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 155.

- ^ a b Tibaldi et al. 2008, p. 154.

- ^ Tibaldi et al. 2008, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d Wörner, Gerhard; Hammerschmidt, Konrad; Henjes-Kunst, Friedhelm; Lezaun, Judith; Wilke, Hans (2000-12-01). "Geochronology (40Ar/39Ar, K-Ar and He-exposure ages) of Cenozoic magmatic rocks from Northern Chile (18-22°S): implications for magmatism and tectonic evolution of the central Andes". Revista Geológica de Chile. 27 (2): 205–240. ISSN 0716-0208.

- ^ Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 145.

- ^ Németh, Károly; Palmer, Julie (1 November 2019). "Geological mapping of volcanic terrains: Discussion on concepts, facies models, scales, and resolutions from New Zealand perspective". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 385: 28. Bibcode:2019JVGR..385...27N. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2018.11.028. ISSN 0377-0273. S2CID 133834335.

- ^ a b Knoche 1932, p. 101.

- ^ Baschin 1934, p. 63.

- ^ a b Hastenrath, Stefan L. (1971). "On the Pleistocene Snow-Line Depression in the Arid Regions of the South American Andes". Journal of Glaciology. 10 (59): 257. Bibcode:1971JGlac..10..255H. doi:10.3189/S0022143000013228. ISSN 0022-1430.

- ^ Baschin 1934, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1299.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 231.

- ^ a b c Francis & Wells 1988, p. 267.

- ^ a b Francis & Silva 1989, p. 251.

- ^ Shea & Vries 2008, p. 683.

- ^ a b Francis & Wells 1988, p. 265.

- ^ Shea & Vries 2008, p. 663.

- ^ a b c d e f Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 151.

- ^ Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 143.

- ^ Francis & Silva 1989, pp. 250, 251.

- ^ Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 242.

- ^ Tibaldi et al. 2008, p. 170.

- ^ a b Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 154.

- ^ a b Tibaldi et al. 2008, p. 169.

- ^ Tibaldi et al. 2008, p. 168.

- ^ Vezzoli et al. 2008, pp. 152, 153.

- ^ a b Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 232.

- ^ Cuthbert, S.J. (1 January 1989). "Reaction rim". Petrology. Encyclopedia of Earth Science. Springer US. pp. 500–503. doi:10.1007/0-387-30845-8_212. ISBN 978-0-442-20623-9.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1302.

- ^ a b Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1309.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1310.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1312.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1313.

- ^ Schmitt, A. K. (2000-03-01). "The Merzbacher & Eggler (1984) Geohygrometer: a Cautionary Note on its Suitability for High-K Suites". Journal of Petrology. 41 (3): 357–362. Bibcode:2000JPet...41..357S. doi:10.1093/petrology/41.3.357. ISSN 0022-3530.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1322.

- ^ Feeley & Sharp 1995, p. 240.

- ^ Feeley & Sharp 1995, p. 248.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1326.

- ^ Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 243.

- ^ a b Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1329.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1330.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, p. 1332.

- ^ Feeley & Sharp 1995, p. 250.

- ^ Mattioli et al. 2006, p. 101.

- ^ a b Jay, J. A.; Welch, M.; Pritchard, M. E.; Mares, P. J.; Mnich, M. E.; Melkonian, A. K.; Aguilera, F.; Naranjo, J. A.; Sunagua, M. (2013-01-01). "Volcanic hotspots of the central and southern Andes as seen from space by ASTER and MODVOLC between the years 2000 and 2010". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 380 (1): 169, 172. Bibcode:2013GSLSP.380..161J. doi:10.1144/SP380.1. ISSN 0305-8719. S2CID 129450763.

- ^ Rudolph 1951, p. 112.

- ^ Francis & Silva 1989, p. 247.

- ^ Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Tamburello et al. 2014, p. 4964.

- ^ Klemetti, Erik W.; Grunder, Anita L. (2008-03-01). "Volcanic evolution of Volcán Aucanquilcha: a long-lived dacite volcano in the Central Andes of northern Chile". Bulletin of Volcanology. 70 (5): 647. Bibcode:2008BVol...70..633K. doi:10.1007/s00445-007-0158-x. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 140668081.

- ^ a b c Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 226.

- ^ a b c Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 227.

- ^ a b c d e Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 141.

- ^ a b Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 152.

- ^ Vezzoli et al. 2008, p. 153.

- ^ Blake, S. (1990). "Viscoplastic Models of Lava Domes". Lava Flows and Domes. IAVCEI Proceedings in Volcanology. Vol. 2. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. p. 93. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74379-5_5. ISBN 978-3-642-74381-8.

- ^ a b c d Feeley, Davidson & Armendia 1993, p. 228.

- ^ Medialdea, Alicia; May, Simon Matthias; Brill, Dominik; King, Georgina; Ritter, Benedikt; Wennrich, Volker; Bartz, Melanie; Zander, Anja; Kuiper, Klaudia; Hurtado, Santiago; Hoffmeister, Dirk; Schulte, Philipp; Gröbner, Marie; Opitz, Stephan; Brückner, Helmut; Bubenzer, Olaf (1 January 2020). "Identification of humid periods in the Atacama Desert through hillslope activity established by infrared stimulated luminescence (IRSL) dating". Global and Planetary Change. 185: 9. Bibcode:2020GPC...18503086M. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.103086. hdl:1871.1/b0bea7ff-0aa7-4901-b17a-5b5bc285768d. ISSN 0921-8181. S2CID 214198721.

- ^ Feeley & Davidson 1994, pp. 1298, 1299.

- ^ Vezzoli et al. 2008, pp. 149, 150.

- ^ Tamburello et al. 2014, p. 4962.

- ^ Galaz-Mandakovic, Damir; Rivera, Francisco (15 March 2023). "Bolivian migration and ethnic subsidiarity in Chilean sulphur and borax high-altitude mining (1888–1946)". History and Anthropology. 34 (2): 251. doi:10.1080/02757206.2020.1862106.

- ^ Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 101.

- ^ Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 98.

- ^ Pritchard et al. 2014, p. 91.

- ^ a b Rivera 2018, p. 89.

- ^ Rivera & Lorca 2024, p. 206.

- ^ Rivera 2018, p. 94.

- ^ Rivera & Lorca 2024, p. 213.

- ^ a b c Rivera 2018, p. 90.

- ^ Rivera & Lorca 2024, pp. 204–205.

- ^ a b c Rivera, Lorca & González 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Rivera 2018, p. 102.

- ^ Rudolph 1951, p. 104.

- ^ Rivera, Lorca & González 2018, p. 16.

- ^ Rivera & Lorca 2024, p. 209.

- ^ a b Rivera 2018, p. 91.

- ^ Rivera 2018, p. 108.

- ^ Rivera, Lorca & González 2018, p. 13.

- ^ a b Rivera 2018, p. 88.

- ^ Rivera 2018, p. 87.

- ^ Rivera & Lorca 2024, p. 211.

- ^ Rivera 2018, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Rivera 2018, p. 99.

- ^ Rivera 2018, p. 101.

Sources

[edit]- Baschin, O. (January 1934). "Geographische Mitteilungen". Die Naturwissenschaften (in German). 22 (4): 62–64. Bibcode:1934NW.....22...62B. doi:10.1007/BF01498754. S2CID 20425799.

- Feeley, T. C.; Davidson, J. P. (1994-10-01). "Petrology of Calc-Alkaline Lavas at Volcan Ollag e and the Origin of Compositional Diversity at Central Andean Stratovolcanoes". Journal of Petrology. 35 (5): 1295–1340. Bibcode:1994JPet...35.1295F. doi:10.1093/petrology/35.5.1295. ISSN 0022-3530.

- Feeley, Todd C.; Davidson, Jon P.; Armendia, Adolfo (1993). "The volcanic and magmatic evolution of Volcán Ollagüe, a high-K, late quaternary stratovolcano in the Andean Central Volcanic Zone". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 54 (3–4): 221–245. Bibcode:1993JVGR...54..221F. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(93)90065-y.

- Feeley, T.C.; Sharp, Z.D. (1995). "18O16O isotope geochemistry of silicic lava flows erupted from Volcán Ollagüe, Andean Central Volcanic Zone". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 133 (3–4): 239–254. Bibcode:1995E&PSL.133..239F. doi:10.1016/0012-821x(95)00094-s.

- Francis, P.W.; Silva, S.L. De (April–June 1989). "Application of the Landsat Thematic Mapper to the identification of potentially active volcanoes in the central Andes". Remote Sensing of Environment. 28: 245–255. Bibcode:1989RSEnv..28..245F. doi:10.1016/0034-4257(89)90117-x.

- Francis, P. W.; Wells, G. L. (1988-07-01). "Landsat Thematic Mapper observations of debris avalanche deposits in the Central Andes". Bulletin of Volcanology. 50 (4): 258–278. Bibcode:1988BVol...50..258F. doi:10.1007/BF01047488. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 128824938.

- Mattioli, Michele; Renzulli, Alberto; Menna, Michele; Holm, Paul M. (2006-11-01). "Rapid ascent and contamination of magmas through the thick crust of the CVZ (Andes, Ollagüe region): Evidence from a nearly aphyric high-K andesite with skeletal olivines". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. Interaction between volcanoes and their basement. 158 (1–2): 87–105. Bibcode:2006JVGR..158...87M. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.04.019.

- Németh, K.; Kereszturi, G. (1 November 2015). "Monogenetic volcanism: personal views and discussion". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 104 (8): 2131–2146. Bibcode:2015IJEaS.104.2131N. doi:10.1007/s00531-015-1243-6. ISSN 1437-3254. S2CID 126749618.

- Knoche, Walter (1932). "Verdunstungseis auf dem Anden-Vulkan Oyahue". Z. Gletscherkunde (in German). 20: 101–102.

- Pritchard, M. E.; Henderson, S. T.; Jay, J. A.; Soler, V.; Krzesni, D. A.; Button, N. E.; Welch, M. D.; Semple, A. G.; Glass, B. (2014-06-01). "Reconnaissance earthquake studies at nine volcanic areas of the central Andes with coincident satellite thermal and InSAR observations". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 280: 90–103. Bibcode:2014JVGR..280...90P. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.05.004.

- Rivera, Francisco (2018). "Cicatrices materiales y espacios industriales en Ollagüe, norte de Chile". Revista de Arqueología Americana (in Spanish) (36): 85–118. ISSN 2663-4066.

- Rivera, Francisco; Lorca, Rodrigo; González, Paula (1 June 2018). "Post-preservación industrial en Ollagüe: un breve elogio de la decadencia". Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología (in Spanish): 9–29. ISSN 0716-5730.

- Rivera, Francisco; Lorca, Rodrigo (1 July 2024). "Más que tarros y latas: modernización, materialidades y prácticas de consumo en tres campamentos azufreros de Ollagüe (1890-1992)". Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología (in Spanish) (56): 203–232. doi:10.56575/BSCHA.05600240828. ISSN 2735-7651.

- Rudolph, William E. (1951-01-01). "Chuquicamata Twenty Years Later". Geographical Review. 41 (1): 88–113. doi:10.2307/211310. JSTOR 211310.

- Shea, Thomas; Vries, Benjamin van Wyk de (2008-08-01). "Structural analysis and analogue modeling of the kinematics and dynamics of rockslide avalanches". Geosphere. 4 (4): 657–686. Bibcode:2008Geosp...4..657S. doi:10.1130/GES00131.1. ISSN 1553-040X.

- Tamburello, G.; Hansteen, T. H.; Bredemeyer, S.; Aiuppa, A.; Tassi, F. (2014-07-28). "Gas emissions from five volcanoes in northern Chile and implications for the volatiles budget of the Central Volcanic Zone" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 41 (14): 2014GL060653. Bibcode:2014GeoRL..41.4961T. doi:10.1002/2014GL060653. hdl:10447/99158. ISSN 1944-8007.

- Tibaldi, Alessandro; Corazzato, Claudia; Kozhurin, Andrey; Lagmay, Alfredo F. M.; Pasquarè, Federico A.; Ponomareva, Vera V.; Rust, Derek; Tormey, Daniel; Vezzoli, Luigina (2008-04-01). "Influence of substrate tectonic heritage on the evolution of composite volcanoes: Predicting sites of flank eruption, lateral collapse, and erosion". Global and Planetary Change. 61 (3–4): 151–174. Bibcode:2008GPC....61..151T. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2007.08.014.

- Vezzoli, Luigina; Tibaldi, Alessandro; Renzulli, Alberto; Menna, Michele; Flude, Stephanie (2008-03-30). "Faulting-assisted lateral collapses and influence on shallow magma feeding system at Ollagüe volcano (Central Volcanic Zone, Chile-Bolivia Andes)". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 171 (1–2): 137–159. Bibcode:2008JVGR..171..137V. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2007.11.015.

External links

[edit]- Population data and map of San Pedro de Quemes Municipality

- "Ollagüe". Peakware.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- AVA