Sexual objectification

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2023) |

Sexual objectification is the act of treating a person solely as an object of sexual desire (a sex object). Objectification more broadly means treating a person as a commodity or an object without regard to their personality or dignity. Objectification is most commonly examined at the level of a society (sociology), but can also refer to the behavior of individuals (psychology), and is a type of dehumanization.

Although both men and women can be sexually objectified, the concept is mainly associated with the objectification of women, and is an important idea in many feminist theories, and psychological theories derived from them. Many feminists argue that sexual objectification of girls and women contributes to gender inequality, and many psychologists associate objectification with a range of physical and mental health risks in women. Research suggests that the psychological effects of objectification of men are similar to those of women, leading to negative body image among men. The concept of sexual objectification is controversial, and some feminists and psychologists have argued that at least some degree of objectification is a normal part of human sexuality.[1][2][3]

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Sexual objectification of women

[edit]General

[edit]The sexual objectification of women involves them being viewed primarily as an object of heteronormative male sexual desire, rather than as a whole person.[4][5][6] Although opinions differ as to which situations are objectionable, many see the objectification of women taking place in the sexually oriented depictions of women in advertising, art and media, pornography, the occupations of stripping and prostitution, and women being brazenly evaluated or judged sexually or aesthetically in public spaces and events, such as beauty contests.[7]

Some feminists and psychologists[8] argue that sexual objectification can lead to negative psychological effects including eating disorders, depression and sexual dysfunction, and can give women negative self-images because of the belief that their intelligence and competence are currently not being, nor will ever be, acknowledged by society.[6] Sexual objectification of women has also been found to negatively affect women's performance, confidence, and level of position in the workplace.[9] How objectification has affected women and society in general is a topic of academic debate, with some saying girls' understanding of the importance of appearance in society may contribute to feelings of fear, shame, and disgust during the transition to womanhood,[10] and others saying that young women are especially susceptible to objectification, as they are often taught that power, respect, and wealth can be derived from one's outward appearance.[11]

Sexual objectification of men

[edit]

General

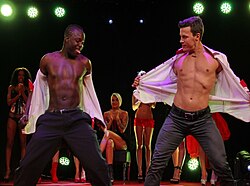

[edit]"Male sexual objectification" involves a man being in public in a sexual context.

Instances where men may be viewed as sexualized can be in advertisements, music videos, films, television shows, beefcake calendars, women's magazines, male strip shows, and clothed female/nude male (CFNM) events.[12] Women also purchase and consume pornography.[13]

In her 1992 book, Sexual Reality: A Virtual Sex World Reader, feminist Susie Bright dedicated a chapter to a salon gathering she co-hosted with fellow feminists Laura Miller, Amy Wallace, and Lisa Palac at Wallace's Berkeley Hills mansion, attended by 16 women writers and served by fully nude men they called "slaveboys". The hosts had advertised for "slaveboys" in the San Francisco Weekly, stating, "Genteel and Bohemian gathering of women writers requires comely slaveboys to serve at our tea party. You will serve nude and will not speak unless spoken to. [...]". The ad received about 100 responses, from which six were selected after "nude auditions". The "slaveboys" served tea and meals, provided foot massages, polished nails, brushed hair, tended the fire, and posed for photographs with the guests. Bright also addresses criticism from unattended friends who called the setup "reverse sexism", to which she responded unapologetically, adding a note of regret for not having sex with them.[14]

Within gay male communities, men are often objectified.[15] In 2007 a study found discussing negative effects of objectification was met with considerable resistance in the community. The sexual objectification of men of color may force them to play specific roles in sexual encounters that are not necessarily of their own choosing.[16]

Research suggests that the psychological effects of objectification on men are similar to those of women, leading to negative body image among men.[17]

Media

[edit]Men's bodies have become more objectified than they previously were, though because of society's established gaze on the objectification of women, the newfound objectification of men is not as widespread.[18] Even with this increase of male objectification, men are still seen as the dominant figures and so the focus is still primarily on women.[19]

Male sexual objectification has been found in 37% of advertisements featuring men's body parts to showcase a product.[20] Similar to the issues of sexual objectification in women, it is common for said objectification to lead men to body shaming, eating disorders, and a drive for perfection. The continued exposure of these "ideal" men subject society to expect all men to fit this role.[21]

Male actors featured in TV shows and movies are oftentimes in excellent shape and have the "ideal" bodies. These men often fill the leading roles. When society is subjected to men who do not have ideal bodies, we typically see them as the comic relief. It is rare to see an out of shape man have a leading role. Leanne Dawson writes that "There are temporal, cultural and geographical "norms" of gender and other aspects of identity, which are often incorrectly considered to be inherent or natural."[22]

In the media, the ideal version of a man is seen as a strong, toned man. The idealized version of a woman is thin.[23] Body evaluation is more commonly used to criticize women than men, and it can take different forms for men. For example, body evaluation is often directed at men's nonverbal cues. By contrast, women more often are subject to body evaluation in the form of sexual, sometimes offensive, verbal remarks. Men tend to experience this from other men, whereas women experience it from both sexes.[20] The Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale (ISOS) is a scale that shows sexual objectification of respondents, both men and women. While experiencing sexual objectification it creates the need to constantly maintain and critique one's physical appearance. This leads to other things like eating disorders, body shaming, and anxiety. The ISOS scale can be related to objectification theory and sexism.[20] Self-objectification, which is the way in which people evaluate themselves, is concentrated more on women. Men typically experience it through media display. To the extent that men do experience self-objectification, studies have shown that men typically do not experience its negative effects to the extent that women do.[24][23]

In the media, sexual objectification has been used as a way to sell products to the general public.[25][26] Sexual objectification has been used as a marketing strategy for many decades according to the Journal of Advertising. This specific strategy targets the public in selling products that will make them look and feel desirable and attractive. It is stated that this strategy sells well by grabbing the attention of the public. The journal states that explicit advertisements do better in marketing than other non-explicit ads.[27]

Views on sexual objectification

[edit]While the concept of sexual objectification is important within feminist theory, ideas vary widely on what constitutes sexual objectification and what are the ethical implications of such objectification. Some feminists such as Naomi Wolf find the concept of physical attractiveness itself to be problematic,[28] with some radical feminists being opposed to any evaluation of another person's sexual attractiveness based on physical characteristics.[citation needed] John Stoltenberg goes so far as to condemn as wrongfully objectifying any sexual fantasy that involves the visualization of a woman.[29]

Radical feminists view objectification as playing a central role in reducing women to what they refer to as the "oppressed sex class".[This quote needs a citation] While some feminists view mass media in societies that they argue are patriarchal as objectifying, they often focus on pornography as playing an egregious role in habituating men to objectify women.[30]

Cultural critics such as Robert Jensen and Sut Jhally accuse mass media and advertising of promoting the objectification of women to help promote goods and services,[7][31][32] and the television and film industries are commonly accused of normalizing the sexual objectification of women.[33]

The objection to the objectification of women is not a recent phenomenon. In the French Enlightenment, for example, there was a debate as to whether a woman's breasts were merely a sensual enticement or rather a natural gift. In Alexandre Guillaume Mouslier de Moissy's 1771 play The True Mother (La Vraie Mère), the title character rebukes her husband for treating her as merely an object for his sexual gratification: "Are your senses so gross as to look on these breasts – the respectable treasures of nature – as merely an embellishment, destined to ornament the chest of women?"[34]

The issues concerning sexual objectification became first problemized during the 1970s by feminist groups. Since then, it has been argued that the phenomenon of female sexual objectification has increased drastically since its problematization in all levels of life, and has resulted in negative consequences for women, especially in the political sphere. However, a rising form of new third-waver feminist groups have also taken the increased objectification of women as an opportunity to use the female body as a mode of power.[35]

Some social conservatives have taken up aspects of the feminist critique of sexual objectification. In their view, however, the increase in the sexual objectification of both sexes in Western culture is one of the negative legacies of the sexual revolution.[36][37][38][39][40] These critics, notably Wendy Shalit, advocate a return to pre-sexual revolution standards of sexual morality, which Shalit refers to as a "return to modesty", as an antidote to sexual objectification.[37][41] Some social conservatives have argued that the feminist movement itself has contributed to the problem of the sexual objectification of women by promoting "free" love (i.e. men and women choosing to have non-reproductive sex outside of marriage and for their own pleasure).[8][42]

Others such as civil libertarians and sex-positive feminists contest feminist claims about the objectification of women. Camille Paglia holds that "[t]urning people into sex objects is one of the specialties of our species." In her view, objectification is closely tied to (and may even be identical with) the highest human faculties toward conceptualization and aesthetics.[43] Feminist author Wendy Kaminer criticized feminist support for anti-pornography laws, arguing that pornography does not cause sexual violence, and bans on such material infantilize women. She has noted that radical feminists have often allied themselves with the Christian right in supporting these laws and denouncing the depiction of sex in popular culture although the two groups strongly disagree on virtually everything else.[44] Her ACLU colleagues Nadine Strossen and Nan D. Hunter have made similar criticisms.[45][46] Strossen has argued that objectification is not in and of itself dehumanizing, and may fulfill women's own fantasies.[47] Psychologist Nigel Barber argues that men, and to a lesser extent, women, are naturally inclined to focus on the physical attractiveness of the opposite sex (or the same sex in the case of gays and lesbians), and that this has been widely misinterpreted as sexism.[2]

Female self-objectification

[edit]

Ariel Levy contends that Western women who exploit their sexuality by, for example, wearing revealing clothing and engaging in lewd behavior, engage in female self-objectification, meaning they objectify themselves. While some women see such behaviour as a form of empowerment, Levy contends that it has led to greater emphasis on a physical criterion or sexualization for women's perceived self-worth, which Levy calls "raunch culture".[48] In a study conducted by the State University of New York, it is found that women self-objectify when trying to fit the "perfect" female standard according to the male gaze.

Levy discusses this phenomenon in Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture. Levy followed the camera crew from the Girls Gone Wild video series, and argues that contemporary America's sexualized culture not only objectifies women, it encourages women to objectify themselves.[49] In today's culture, Levy writes, the idea of a woman participating in a wet T-shirt contest or being comfortable watching explicit pornography has become a symbol of feminist strength.

Jordan Peterson has asked why women need to wear make-up or high-heels in the workplace, that a double standard exists for sexual harassment and females who self-objectify themselves in society.[50]

Social media has made a major impact on the self-objectification of women. Through social media, women self-objectify by posting provocative images they know will be objectified by their viewers as a form of seeking validation of posting images that fits the mold of society.[51]

Latina women

[edit]Latina women face a particular form of sexual objectification based on stereotypes relating to Latina women. American media often portrays Latina women as being sexually promiscuous and curvaceous, having large breasts and buttocks, being melodramatic, or having a feisty attitude.[52] Keller identifies three main stereotypes that contribute to the objectification of Latinas. (Cantina Girl, Suffering Senorita, and Vamp). The “Cantina Girl” is characterized as being an alluring sexual presence. The “Suffering Senorita” is the Latina who goes “bad” due to her love of the (usually Anglo) love interest. Lastly, the “Vamp” is seen as beautiful but devious, and a psychological threat for her wit or charm.[53] All three of these categorizations stem from the sexual objectification of Latina women's bodies and identities.

Such sexual objectifications hold real-world consequences for Latina women. For instance, the prevalence of negative Latina stereotypes (such as hypersexualization) has led to a decrease in positive in-group attitudes among the Latina community.[54]

Black women

[edit]Black women have been fetishized and objectified throughout history. They may be portrayed as having a more animalistic nature than their non-black counterparts. People who fetishize black women are sometimes pejoratively said to have "jungle fever".[55]

Black women are widely objectified in the media and in pornography, and are scrutinized more closely for doing the same things as their non-black counterparts.[citation needed] They are also stereotyped in the media as having more curvaceous bodies and bigger lips.[55]

Objectification theory

[edit]This section needs attention from an expert in Gender Studies. The specific problem is: The prose is jargon-filled, repetitive and nearly impenetrable to laypeople. The structure needs improvement. (January 2015) |

Objectification theory is a framework for understanding the experiences of women in cultures that sexually objectify them, proposed by Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts in 1997.[56] Within this framework, Fredrickson and Roberts draw conclusions about women's experiences. This theory states that, because of sexual objectification, women learn to internalize an outsider's view of their bodies as the primary view of themselves. Women, they explain, begin to view their bodies as objects separate from their person. This internalization has been termed self-objectification. This theory does not seek to prove the existence of sexual objectification; the theory assumes its existence in culture. This self-objectification then, according to objectification theory, leads to increased habitual body monitoring. With this framework in mind, Fredrickson and Roberts suggest explanations for consequences they believe are the result of sexual objectification. The consequences suggested are: increased feelings of shame, increased feelings of anxiety, decreased peak motivational state, and decreased awareness of internal bodily states.

Sexual objectification has been studied based on the proposition that girls and women develop their primary view of their physical selves from observing others. These observations can take place in the media or through personal experience.[57]: 26 Through a blend of expected and actual exposure, women are socialized to objectify their own physical characteristics from a third-person perception, which is identified as self-objectification.[58] Women and girls develop an expected physical appearance for themselves, based on observations of others; and are aware that others are likely to observe as well. The sexual objectification and self-objectification of women is believed to influence social gender roles and inequalities between the sexes.[59]

Self-objectification

[edit]Self-objectification can increase in situations which heighten the awareness of an individual's physical appearance.[60]: 82 Here, the presence of a third-person observer is enhanced. Therefore, when individuals know others are looking at them, or will be looking at them, they are more likely to care about their physical appearance. Examples of the enhanced presence of an observer include the presence of an audience, camera, or other known observer.

Women, girls, and self-objectification

[edit]Primarily, objectification theory describes how women and girls are influenced as a result of expected social and gender roles.[57] Research indicates not all women are influenced equally, due to the anatomical, hormonal, and genetic differences of the female body; however, women's bodies are often objectified and evaluated more frequently.[60]: 90–95 Self-objectification in girls tends to stem from two main causes: the internalization of traditional beauty standards as translated through media as well as any instances of sexual objectification that they might encounter in their daily lives.[61] It is not uncommon for women to translate their anxieties over their constant sense of objectification into obsessive self-surveillance. This, in turn, can lead to many serious problems in women and girls, including "body shame, anxiety, negative attitudes toward menstruation, a disrupted flow of consciousness, diminished awareness of internal bodily states, depression, sexual dysfunction, and disordered eating."[62]

Sexual objectification occurs when a person is identified by their sexual body parts or sexual function. In essence, an individual loses their identity, and is recognized solely by the physical characteristics of their body.[57] The purpose of this recognition is to bring enjoyment to others, or to serve as a sexual object for society.[5] Sexual objectification can occur as a social construct among individuals.

Sexual objectification has been around and present in society for many but has increased with the introduction of social media according to “Objectification, Sexualization, and Misrepresentation: Social Media and the College Experience - Stefanie E Davis, 2018” This journal shows a clear explanation for how young girls are influenced by social media to be sexually objectified. The platform is meant to share a glimpse into a person's life through photos to share with friends, family and mutuals. For many individuals, social media applications like Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, and X (formerly Twitter) are used to glamorize and romanticize certain lifestyles. Examples of this can be young women using their platform (however big it may be) to pose as an older age by uploading provocative photos. This behavior promotes sexual objectification of young girls that participate on social media.

Psychological consequences

[edit]Objectification theory suggests both direct and indirect consequences of objectification to women. Indirect consequences include self consciousness in terms that a woman is consistently checking or rearranging her clothes or appearance to ensure that she is presentable. More direct consequences are related to sexual victimization. Rape and sexual harassment are examples of this.[8] Doob (2012) states that sexual harassment is one of the challenges faced by women in workplace. This may constitute sexual jokes or comments, most of which are degrading.[63] Research indicates that objectification theory is valuable to understanding how repeated visual images in the media are socialized and translated into mental health problems, including psychological consequences on the individual and societal level.[8] These include increased self-consciousness, increased body anxiety, heightened mental health threats (depression, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and sexual dysfunction), and increased body shame.[64] Therefore, the theory has been used to explore an array of dependent variables including disordered eating, mental health, depression, motor performance, body image, idealized body type, stereotype formation, sexual perception and sexual typing.[8][60] Body shame is a byproduct of the concept of an idealized body type adopted by most Western cultures that depicts a thin, model-type figure. Thus, women will engage in actions meant to change their body such as dieting, exercise, eating disorders, cosmetic surgery, etc.[8] Effects of objectification theory are identified on both the individual and societal levels.

Causes of depression

[edit]Learned helplessness theory posits that because human bodies are only alterable to a certain point, people develop a sense of body shame and anxiety from which they create a feeling of helplessness in relation to correcting their physical appearance and helplessness in being able to control the way in which others perceive their appearance. This lack of control often results in depression.[8] In relating to a lack of motivation, objectification theory states that women have less control in relationships and the work environment because they have to depend on the evaluation of another who is typically basing their evaluation on physical appearance. Since the dependence on another's evaluation limits a woman's ability to create her own positive experiences and motivation, it adversely increases her likelihood for depression.[8] Furthermore, sexual victimization may be a cause. Specifically, victimization within the workplace degrades women. Harassment experienced every day wears on a woman, and sometimes this results in a state of depression.[8][63]

Alternatives and critique

[edit]Ann J. Cahill uses the concept of derivitization as an alternative to objectification when trying to address sexual objectification's seeming judgment of all physical interactions (termed somatophobia by Cahill). Cahill criticizes the notion of objectification as marginalizing the role of the body in one's subjective experience and therefore making it impossible to understand how being viewed as a sexually appealing body can enhance an individual's notion of self.[65] : 842

Instead, Cahill uses the concept of subjectivity from the study of intersubjectivity. A subject is an individual with their unique experience of reality. Derivitization is then defined as limiting another person's subjective behaviour and experience to align with or serve your own subjective experience. In this framing, the objectification exists in sex work is viewed instead as the derivitization of having another act for only one's own subjective experience and ignoring the sex worker's experience. Drawing comparisons to the doctor–patient relationship, Cahill argues that a recognition of what both people bring to a relationship and their subjective goals is what makes a relationship ethical.[65]: 843–847

Free use

[edit]"Free use" describes a sexual fetish involving being consensually "used" as a sex object at any time and anywhere by a sexual partner when they are aroused, including while doing chores or while sleeping. It became popular online in the mid-2020s, including in gay pornography, on Reddit—where one subreddit dedicated to the fetish had over 1.4 million members by 2023—and on TikTok.[66][67]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Paglia, Camille (10 September 1990). Sexual Personae. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300182132. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ a b Barber, Nigel. "Objectification Is a Basic Aspect of Male Sexuality". Psychology Today. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Strossen, Nadine (2000). Defending Pornography. NYU Press. p. 136. ISBN 0814781497. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Barry, Kathleen (1984). "Pornography: the ideoloy of cultural sadism". In Barry, Kathleen (ed.). Female sexual slavery. New York London: NYU Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-8147-1069-2.

- ^ a b LeMoncheck, Linda (1997). "I only do it for the money: pornography, prostitution, and the business of sex". In LeMoncheck, Linda (ed.). Loose women, lecherous men a feminist philosophy of sex. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-19-510556-8.

- ^ a b Szymanski, Dawn M.; Moffitt, Lauren B.; Carr, Erika R. (January 2011). "Sexual objectification of women: advances to theory and research" (PDF). The Counseling Psychologist. 39 (1): 6–38. doi:10.1177/0011000010378402. S2CID 17954950.

- ^ a b Jhally, Sut (director) (1997). Dreamworlds II: desire, sex, power in music (Documentary). USA: Media Education Foundation.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fredrickson, Barbara L.; Roberts, Tomi-Ann (June 1997). "Objectification theory: toward understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 21 (2): 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x. S2CID 145272074.

- ^ Szymanski, Dawn M.; Moffitt, Lauren B.; Carr, Erika R. (2011). "Sexual Objectification of Women: Advances to Theory and Research" (PDF). The Counseling Psychologist. 39 (1): 6–38. doi:10.1177/0011000010378402. S2CID 17954950. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Lee, Janet (September 1994). "Menarche and the (hetero)sexualization of the female body". Gender & Society. 8 (3): 343–362. doi:10.1177/089124394008003004. S2CID 144282688.

- ^ Report of the American Psychological Association task force on the sexualization of girls, executive summary (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ "Sports, gym classes, team initiations and events". Sensations4women.com. 26 January 1998. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Citations:

- McElroy, Wendy (1995). XXX: a woman's right to pornography. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-312-13626-0.

- "A 'Playgirl" for adult TV". Multichannel News. NewBay Media. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Taormino, Tristan (13 May 2008). "Girls love gay male porn". The Village Voice. Josh Fromson. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Scott, Lisa (15 October 2008). "Women who like to watch gay porn". Metro. DMG Media. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Murphy, Chris (12 May 2015). "Women's porn tastes: You'll never guess what ladies prefer". Daily Mirror. Trinity Mirror.

- ^ Bright, Susie (1992). Susie Bright's Sexual Reality: A Virtual Sex World Reader. Cleis Press. pp. 45–54. ISBN 978-0-939416-58-5. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ Teunis, Niels (May 2007). "Sexual objectification and the construction of whiteness in the gay male community". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 9 (3): 263–275. doi:10.1080/13691050601035597. JSTOR 20460929. PMID 17457730. S2CID 8287617.

- ^ Teunis, Niels (2007). "Sexual objectification and the construction of whiteness in the gay male community". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 9 (3): 263–275. doi:10.1080/13691050601035597. PMID 17457730. S2CID 8287617.

- ^ Neimark, Jill (1 November 1994). "The beefcaking of America". Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Kellie, Dax J.; Blake, Khandis R.; Brooks, Robert C. (23 August 2019). "What drives female objectification? An investigation of appearance-based interpersonal perceptions and the objectification of women". PLOS ONE. 14 (8): e0221388. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1421388K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221388. PMC 6707629. PMID 31442260.

- ^ Tortajada-Giménez, Iolanda; Araüna-Baró, Núria; Martínez-Martínez, Inmaculada José (2013). "Advertising stereotypes and gender representation in social networking sites". Comunicar. 21 (41): 177–186. doi:10.3916/C41-2013-17. hdl:10272/7056. Original Spanish article.

- ^ a b c Davidson, M. Meghan; Gervais, Sarah J.; Canivez, Gary L.; Cole, Brian P. (April 2013). "A psychometric examination of the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale among college men". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 60 (2): 239–250. doi:10.1037/a0032075. PMID 23458607.

- ^ Buchbinder, David (Winter 2004). "Object or ground? The male body as fashion accessory". Canadian Review of American Studies. 34 (3): 221–232. doi:10.1353/crv.2006.0030. S2CID 161493223.

- ^ Dawson, Leanne (2015). "Passing and policing: controlling compassion, bodies and boundaries in Boys Don't Cry and Unveiled/Fremde Haut" (PDF). Studies in European Cinema. 12 (3): 205–228. doi:10.1080/17411548.2015.1094258. hdl:20.500.11820/8f102aab-aa8c-4524-8cc1-18ff25ed0467. S2CID 147349266.

- ^ a b Stevens Aubrey, Jennifer (27 May 2003). Investigating the role of self-objectification in the relationship between media exposure and sexual self-perceptions. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Marriott Hotel, San Diego, CA, May 27, 2003.

- See also: Stevens Aubrey, Jennifer (June 2006). "Effects of sexually objectifying media on self-objectification and body surveillance in undergraduates: results of a 2-year panel study". Journal of Communication. 56 (2): 366–386. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00024.x.

- ^ Roberts, Tomi-Ann; Gettman, Jennifer Y. (1 July 2004). "Mere Exposure: Gender Differences in the Negative Effects of Priming a State of Self-Objectification". Sex Roles. 51 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000032306.20462.22. ISSN 1573-2762. S2CID 55703429.

- ^ Zimmerman, Amanda; Dahlberg, John (1 March 2008). "The Sexual Objectification of Women in Advertising: A Contemporary Cultural Perspective". Journal of Advertising Research. 48 (1): 71–79. doi:10.2501/S0021849908080094. ISSN 0021-8499. S2CID 30977582.

- ^ Vargas-Bianchi, Lizardo; Mensa, Marta (1 January 2020). "Do you remember me? Women sexual objectification in advertising among young consumers". Young Consumers. 21 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1108/YC-04-2019-0994. ISSN 1747-3616. S2CID 216353566.

- ^ Martin, Brett A. S.; Lang, Bodo; Wong, Stephanie (2003). "Conclusion Explicitness in Advertising: The Moderating Role of Need for Cognition (NFC) and Argument Quality (AQ) on Persuasion". Journal of Advertising. 32 (4): 57–65. doi:10.1080/00913367.2003.10639148. ISSN 0091-3367. JSTOR 4622179. S2CID 140844572. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ Wolf, Naomi (2002) [1992]. The beauty myth: how images of beauty are used against women. New York: Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-051218-7.

- ^ Stoltenberg, John (2000). "Sexual objectification and male supremacy" (PDF). Refusing to be a man: essays on sex and justice. London New York: UCL Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-84142-041-7.

- ^ MacKinnon, Catharine (1993). Only words. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-63934-8.

- ^ Jensen, Robert (1997). "Using pornography". In Dines, Gail; Jensen, Robert; Russo, Ann (eds.). Pornography: the production and consumption of inequality. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-19-510556-8.

- ^ Frith, Katherine; Shaw, Ping; Cheng, Hong (March 2005). "The construction of beauty: a cross-cultural analysis of women's magazine advertising". Journal of Communication. 55 (1): 56–70. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02658.x.

- ^ balembbn (15 April 2013). "Representations of Women in Reality TV". Feminism and Film (blog). Archived from the original on 14 April 2019 – via Vanderbilt University.

- ^ Schama, Simon (1989). "The cultural construction of a citizen: II Casting roles: children of nature". In Schama, Simon (ed.). Citizens: a chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Knopf Distributed by Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-55948-3.

- ^ Heldman, Caroline (August 2011). "Sexualizing Sarah Palin: the social and political context of the sexual objectification of female candidates". Sex Roles. 65 (3): 156–164. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9984-6. S2CID 141197696.

- ^ "Dr. James Dobson". The Interim: Canada's life and family newspaper. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: via True Media. 12 January 1997. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ a b Shalit, Wendy (2000). A return to modesty: discovering the lost virtue. New York: Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-684-86317-7.

- ^ Reisman, Judith A. (1991). "Soft porn" plays hardball: its tragic effects on women, children, and the family. Lafayette, Louisiana: Huntington House Publishers. pp. 32–46, 173. ISBN 978-0-910311-92-2.

- ^ Holz, Adam R. (2007). "Is average the new ugly?". Plugged In Online. Focus on the Family.

- ^ National Coalition for the Protection of Children & Families (July 1997). "Subtle Dangers of Pornography (special report by the National Coalition for the Protection of Children & Families)". Pure Intimacy (website). Focus on the Family. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Shalit, Wendy (2000). "Modesty revisited". orthodoxytoday.org. Fr. Johannes Jacobse. Archived from the original on 2018-10-28. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ Abrams, Dominic; Hogg, Michael A. (2004). "Collective identity: group membership and self-conception". In Brewer, Marilynn B.; Hewstone, Miles (eds.). Self and social identity. Perspectives on Social Psychology. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-4051-1069-3.

- ^ Paglia, Camille (1991). Sexual personae: art and decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-73579-3.

- ^ Kaminer, Wendy. "When Conservative Senators Sound Like Anti-Porn Feminists". Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Strossen, Nadine. "Who Really Benefits From the First Amendment". Tablet. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Hunter, Nan D.; Duggan, Lisa (1995). Sex Wars: Sexual Dissent and Political Culture. Routledge. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9780415910378. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Strossen, Nadine (2000). Defending Pornography. NYU Press. pp. 136–165. ISBN 0814781497. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Levy, Ariel (2006). Female chauvinist pigs: women and the rise of raunch culture. London: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-2638-4.

- ^ Dougary, Ginny (25 September 2007). "Yes we are bovvered". The Times. London. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Maples, Miranda (22 March 2018). "Jordan Peterson Questions If Men and Women Can Work Together". Study Breaks.

- ^ Zheng, Dong; Ni, Xiao-li; Luo, Yi-jun (2019-03-01). "Selfie Posting on Social Networking Sites and Female Adolescents' Self-Objectification: The Moderating Role of Imaginary Audience Ideation". Sex Roles. 80 (5): 325–331. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0937-1. ISSN 1573-2762. S2CID 149757000.

- ^ McLaughlin, Bryan; Rodriguez, Nathian S.; Dunn, Joshua A.; Martinez, Jobi (2018-09-03). "Stereotyped Identification: How Identifying with Fictional Latina Characters Increases Acceptance and Stereotyping". Mass Communication and Society. 21 (5): 585–605. doi:10.1080/15205436.2018.1457699. ISSN 1520-5436. S2CID 149715074.

- ^ Merskin, Debra (2007-05-29). "Three Faces of Eva: Perpetuation of The Hot-Latina Stereotype in Desperate Housewives". Howard Journal of Communications. 18 (2): 133–151. doi:10.1080/10646170701309890. ISSN 1064-6175. S2CID 144571909.

- ^ Tukachinsky, Riva; Mastro, Dana; Yarchi, Moran (2017-07-03). "The Effect of Prime Time Television Ethnic/Racial Stereotypes on Latino and Black Americans: A Longitudinal National Level Study". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 61 (3): 538–556. doi:10.1080/08838151.2017.1344669. ISSN 0883-8151. S2CID 148590923.

- ^ a b Bianca, Fransisca (2017). "Fetishism and Sexual Objectification towards African (Black) Women in Modern Society: Analyzing the Portrayal of African Women in the Media". Jurnal Sentris. 1 (1): 91–99. doi:10.26593/sentris.v1i1.4132.91-99. ISSN 2746-3826. S2CID 240601761.

- ^ Fredrickson, B. L.; Roberts, T.-A. (1997). "Objectification Theory". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 21 (2): 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x. S2CID 145272074.

- ^ a b c Bartky, Sandra Lee (1990). "On Psychological Oppression". Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression. New York: Routledge. p. 22-32. ISBN 978-0-415-90186-4.

- ^ Kaschak, Ellyn (1992). Engendered Lives: A New Psychology of Women's Experience. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-465-01349-4.

- ^ Goldenberg, Jamie L.; Roberts, Tomi-Ann (2004). "The Beast within the Beauty: An Existential Perspective on the Objectification and Condemnation of Women". In Greenberg, Jeff; Koole, Sander L.; Pyszczynski, Thomas A. (eds.). Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 71–85. ISBN 978-1-59385-040-1.

- ^ a b c Fredrickson, Barbara L.; Harrison, Kristen (2005). "Throwing like a Girl: Self-Objectification Predicts Adolescent Girls' Motor Performance". Journal of Sport and Social Issues. 29 (1): 79–101. doi:10.1177/0193723504269878. S2CID 146312527.

- ^ McKay, Tajare' (2013). "Female self-objectification: causes, consequences and prevention". McNair Scholars Research Journal. 6 (1): 53–70. ISSN 2166-109X.

- ^ Calogero, Rachel M.; Davis, William N.; Thompson, J. Kevin (2005). "The Role of Self-Objectification in the Experience of Women with Eating Disorders" (PDF). Sex Roles. 52 (1): 43–50. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.413.8397. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-1192-9. S2CID 10241677.

- ^ a b Doob, Christopher B. (2013). Social Inequality and Social Stratification in US Society. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0-205-79241-2.

- ^ Moradi, Bonnie; Huang, Yu-Ping (2008). "Objectification Theory and Psychology of Women: A Decade of Advances and Future Directions". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 32 (4): 377–398. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x. S2CID 144389646.

- ^ a b Cahill, Ann J. (2014). "The Difference Sameness Makes: Objectification, Sex Work, and Queerness". Hypatia. 29 (4): 840–856. doi:10.1111/hypa.12111. ISSN 0887-5367.

- ^ Myers, Jake (22 August 2023). "The 'free use' fetish is sweeping the gay community. Is it ruthless, or a relief?". Queerty. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Magdalene (18 August 2023). "What's the 'Free Use' Fetish, and Why's Everyone Talking About It?". Vice. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Bartky, Sandra Lee (1990). Femininity and domination: studies in the phenomenology of oppression. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-90186-4.

- Berger, John (1972). Ways of Seeing. London: BBC and Penguin Books. ISBN 0-563-12244-7 (BBC), ISBN 0-14-021631-6, ISBN 0-14-013515-4 (pbk).

- Bridges, Ana J.; Johnson, Jennifer A.; Dines, Gail; Condit, Deirdre M.; West, Carolyn M. (April 2015). "Introducing Sexualization, Media & Society". Sexualization, Media, & Society. 1 (1): 487–515. doi:10.1177/2374623815588763.

- Brooks, Gary R. (1995). The centerfold syndrome: how men can overcome objectification and achieve intimacy with women. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-0-7879-0104-2.

- Coy, Maddy; Garner, Maria (November 2010). "Glamour modelling and the marketing of self-sexualization: critical reflections". International Journal of Cultural Studies. 13 (6): 657–675. doi:10.1177/1367877910376576. S2CID 145230875.

- Eames, Elizabeth R. (1976). "Sexism and woman as sex object". Journal of Thought. 11 (2): 140–143. Preview. [Link Broken]

- Holroyd, Julia (2005). Sexual objectification: The unlikely alliance of feminism and Kant (PDF). Society for Applied Philosophy International Congress. Oxford, UK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-05-21. (conference paper)

- LeMoncheck, Linda (1985). Dehumanizing Women: Treating Persons as Sex Objects. New York: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-7386-5.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. (October 1995). "Objectification". Philosophy & Public Affairs. 24 (4): 249–291. doi:10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x. JSTOR 2961930.

- Papadaki, Evangelia (Lina) (August 2007). "Sexual objectification: From Kant to contemporary feminism" (PDF). Contemporary Political Theory. 6 (3): 330–348. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cpt.9300282. S2CID 144197352.

- Parker, Kathleen (30 June 2008). "'Save the males': Ho culture lights fuses, but confuses". Daily News. New York.

- Paul, Pamela (2005). Pornified: how pornography is transforming our lives, our relationships, and our families. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-8132-9.

- Mario Perniola, The Sex-appeal of the inorganic, translated by Massimo Verdicchio, London-New York, Continuum, 2004.

- Sharge, Laurie (April 2005). "Exposing the fallacies of anti-porn feminism". Feminist Theory. 6 (1): 45–65. doi:10.1177/1464700105050226. S2CID 145194517.

- Soble, Alan (2002). Pornography, Sex, and Feminism. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-944-8.

- Ward, L. Monique; Daniels, Elizabeth A.; Zurbriggen, Eileen L.; Rosenscruggs, Danielle (2023). "The sources and consequences of sexual objectification". Nature Reviews Psychology. 2: 496–513. doi:10.1038/s44159-023-00192-x.

External links

[edit]- Papadaki, Evangelia (March 10, 2010), "Feminist perspectives on objectification", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Shrage, Laurie (July 13, 2007), "Feminist perspectives on sex markets: 1.3 sexual objectification", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Steinberg, David (March 5, 1993). "On Sexual Objectification". Spectator Magazine | Comes Naturally column #5. – Sex-positive feminist perspective on sexual objectification.

- Wyatt, Petronella (October 5, 1996). "Women like seeing men as sex objects". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 30, 2008. Interview with Janet Anderson.

- Kalyanaraman, Sriram; Redding, Michael; Steele, Jason (2000). "Sexual suggestiveness in online ads: effects of objectification on opposite genders". psu.edu/dept/medialab. Media Effects Research Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008.

- Davis, Stefanie E (July 13, 2018) "Objectification, Sexualization and Misrepresentation: Social Media and the College Experience" Sage Journals

- Bello, D. C., Pitts, R. E., & Etzel, M. J. (1983). The communication effects of controversial sexual content in television programs and commercials. Journal of Advertising, 12(3), 32–42.

- Hill, M. S., & Fischer, A. R. (2008). Examining objectification theory: Lesbian and heterosexual women's experiences with sexual-and self-objectification. The Counseling Psychologist, 36(5), 745–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000007301669

User-generated content

- Tigtog (March 23, 2007). "FAQ: What is sexual objectification?". finallyfeminism101.wordpress.com. Finally, A Feminism 101 Blog via WordPress.

- Karen Straughan (March 28, 2012). I'm a sexy woman, so stop objectifying me! (Video). Karen Straughan via YouTube. Retrieved June 7, 2017.