Nickel–hydrogen battery

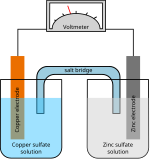

Schematics of a nickel–hydrogen battery | |

| Specific energy | 55–75 W·h/kg[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Energy density | ~60 W·h/L[2] |

| Specific power | ~220 W/kg[3] |

| Charge/discharge efficiency | 85% |

| Cycle durability | >20,000 cycles[4] |

A nickel–hydrogen battery (NiH2 or Ni–H2) is a rechargeable electrochemical power source based on nickel and hydrogen.[5] It differs from a nickel–metal hydride (NiMH) battery by the use of hydrogen in gaseous form, stored in a pressurized cell at up to 1200 psi (82.7 bar) pressure.[6] The nickel–hydrogen battery was patented in the United States on February 25, 1971 by Alexandr Ilich Kloss, Vyacheslav Mikhailovic Sergeev and Boris Ioselevich Tsenter from the Soviet Union.[7]

NiH2 cells using 26% potassium hydroxide (KOH) as an electrolyte have shown a service life of 15 years or more at 80% depth of discharge (DOD)[8] The energy density is 75 Wh/kg, 60 Wh/dm3[2] specific power 220 W/kg.[3] The open-circuit voltage is 1.55 V, the average voltage during discharge is 1.25 V.[9]

While the energy density is only around one third as that of a lithium battery, the distinctive virtue of the nickel–hydrogen battery is its long life: the cells handle more than 20,000 charge cycles[4] with 85% energy efficiency and 100% faradaic efficiency.

NiH2 rechargeable batteries possess properties which make them attractive for the energy storage of electrical energy in satellites[10] and space probes. For example, the ISS,[11] Mercury Messenger,[12] Mars Odyssey[13] and the Mars Global Surveyor[14] are equipped with nickel–hydrogen batteries. The Hubble Space Telescope, when its original batteries were changed in May 2009 more than 19 years after launch, led with the highest number of charge and discharge cycles of any NiH2[15] battery in low Earth orbit.[16]

History

[edit]The development of the nickel hydrogen battery started in 1970 at Comsat[17] and was used for the first time in 1977 aboard the U.S. Navy's Navigation technology satellite-2 (NTS-2).[18] Currently, the major manufacturers of nickel–hydrogen batteries are Eagle-Picher Technologies and Johnson Controls, Inc.

Characteristics

[edit]

The nickel–hydrogen battery combines the positive nickel electrode of a nickel–cadmium battery and the negative electrode, including the catalyst and gas diffusion elements, of a fuel cell. During discharge, hydrogen contained in the pressure vessel is oxidized into water while the nickel oxyhydroxide electrode is reduced to nickel hydroxide. Water is consumed at the nickel electrode and produced at the hydrogen electrode, so the concentration of the potassium hydroxide electrolyte does not change. As the battery discharges, the hydrogen pressure drops, providing a reliable state of charge indicator. In one communication satellite battery, the pressure at full charge was over 500 pounds/square inch (3.4 MPa), dropping to only about 15 PSI (0.1 MPa) at full discharge.

If the cell is over-charged, the oxygen produced at the nickel electrode reacts with the hydrogen present in the cell and forms water; as a consequence the cells can withstand overcharging as long as the heat generated can be dissipated.[dubious – discuss]

The cells have the disadvantage of relatively high self-discharge rate, i.e. chemical reduction of Ni(III) into Ni(II) in the cathode:

which is proportional to the pressure of hydrogen in the cell; in some designs, 50% of the capacity can be lost after only a few days' storage. Self-discharge is less at lower temperature.[1]

Compared with other rechargeable batteries, a nickel–hydrogen battery provides good specific energy of 55–60 watt-hours/kg, and very long cycle life (40,000 cycles at 40% DOD) and operating life (> 15 years) in satellite applications. The cells can tolerate overcharging and accidental polarity reversal, and the hydrogen pressure in the cell provides a good indication of the state of charge. However, the gaseous nature of hydrogen means that the volume efficiency is relatively low (60-100 Wh/L for an IPV (individual pressure vessel) cell), and the high pressure required makes for high-cost pressure vessels.[1]

The positive electrode is made up of a dry sintered[20] porous nickel plaque, which contains nickel hydroxide. The negative hydrogen electrode utilises a teflon-bonded platinum black catalyst at a loading of 7 mg/cm2 and the separator is knit zirconia cloth (ZYK-15 Zircar).[21][22]

The Hubble replacement batteries are produced with a wet slurry process where a binder agent and powdered metallic materials are molded and heated to boil off the liquid.[23]

Designs

[edit]- Individual pressure vessel (IPV) design consists of a single unit of NiH2 cells in a pressure vessel.[24]

- Common pressure vessel (CPV) design consist of two NiH2 cell stacks in series in a common pressure vessel. The CPV provides a slightly higher specific energy than the IPV.

- Single pressure vessel (SPV) design combines up to 22 cells in series in a single pressure vessel.

- Bipolar design is based on thick electrodes, positive-to-negative back-to-back stacked in a SPV.[25]

- Dependent pressure vessel (DPV) cell design offers higher specific energy and reduced cost.[26]

- Common/dependent pressure vessel (C/DPV) is a hybrid of the common pressure vessel (CPV) and the dependent pressure vessel (DPV) with a high volumetric efficiency.[27]

- Schematics

See also

[edit]- List of battery types

- List of battery sizes

- Comparison of battery types

- Nickel–metal hydride battery

- Power-to-weight ratio

- Pressure vessel

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

- Batteries in space

References

[edit]- ^ a b c David Linden, Thomas Reddy (ed.) Handbook of Batteries Third Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2002 ISBN 0-07-135978-8 Chapter 32, "Nickel Hydrogen Batteries"

- ^ a b c Spacecraft Power Systems Pag.9

- ^ a b NASA/CR—2001-210563/PART2 -Pag.10 Archived 2008-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Five-year update: nickel hydrogen industry survey

- ^ "A simplified physics-based model for nickel hydrogen battery" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ^ Nickel–hydrogen spacecraft battery handling and storage practice

- ^ Hermetically sealed nickel–hydrogen storage cell US Patent 3669744

- ^ "Potassium hydroxide electrolyte for long-term nickel–hydrogen geosynchronous missions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ^ Optimization of spacecraft electrical power subsystems -Pag.40

- ^ Ni-H2 Cell Characterization for Intelsat Programs

- ^ Validation of International Space Station electrical performance model via on-orbit telemetry Archived 2009-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NASA.gov

- ^ A lightweight high reliability single battery power system for interplanetary spacecraft

- ^ Mars Global Surveyor Archived 2009-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hubble space telescope servicing mission 4 batteries

- ^ NiH2 reliability impact upon Hubble Space Telescope battery replacement

- ^ "Nickel–Hydrogen Battery Technology—Development and Status" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ NTS-2 Nickel–Hydrogen Battery Performance 31 Archived 2009-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Mission 4 Batteries

- ^ Performance comparison between NiH2 dry sinter and slurry electrode cells

- ^ [1] Archived 2008-08-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Nickel–Hydrogen Batteries

- ^ Hubble space telescope servicing mission 4 batteries

- ^ Nickel hydrogen batteries-an overview Archived 2009-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Development of a large scale bipolar NiH2 battery.

- ^ 1995–dependent pressure vessel (DPV)

- ^ Common/dependent-pressure-vessel nickel–hydrogen Batteries

Further reading

[edit]- Albert H. Zimmerman (ed), Nickel–Hydrogen Batteries Principles and Practice, The Aerospace Press, El Segundo, California. ISBN 1-884989-20-9.

External links

[edit]- Overview of the design, development, and application of nickel–hydrogen batteries

- Implantable nickel hydrogen batteries for bio-power applications

- NASA handbook for nickel–hydrogen batteries

- A nickel/hydrogen battery for terrestrial PV systems

- A microfabricated nickel–hydrogen battery using thick film printing techniques