Neimongosaurus

| Neimongosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous

| |

|---|---|

| |

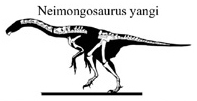

| Skeletal reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Therizinosauroidea |

| Family: | †Therizinosauridae |

| Genus: | †Neimongosaurus Zhang et al., 2001 |

| Type species | |

| †Neimongosaurus yangi Zhang et al., 2001

| |

Neimongosaurus (meaning "Nei Mongol lizard") is a genus of herbivorous therizinosaur theropod dinosaur that lived in China during the Late Cretaceous period. Its fossils are known from the strata of the Iren Dabasu Formation. It is known from two specimens, discovered in 1999 by researchers from the Ministry of Land and Resources and described two years later. One species, N. yangi, is known, named after Chinese palaeontologist Yang Zhongjian.

Discovery and naming

[edit]

In 1999, a team from the Ministry of Land and Resources, based in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, was conducting field work at Sanhangobi, 12 mi (20 km) southwest of Erenhot. The strata they were working in belonged to the Iren Dabasu Formation,[1] which has been variably dated to the Turonian,[2] the Santonian,[3] or the Campanian–Maastrichtian.[4][5] The first specimen, LH V0001, consisted of a partially preserved braincase; the front of the right lower jaw; a nearly complete axial column compromising 15 cervical (including the axis), 4 dorsal and 22 caudal vertebrae; a furcula; both scapulocoracoids; both humeri; left radius; fragmented ilia; both femora; both tibiae; left tarsals and a virtually complete and articulated left pes. The second, LH V0008, consisted of a sacrum composed by 6 sacral vertebrae and both ilia. Both specimens were transported to the Long Hao Institute of Geology and Palaeontology for study. In 2001, Zhang Xiaohong, Xu Xing, Paul Sereno, Kwang Xuewen and Tan Lin assigned them to a new genus and species of therizinosaurid dinosaur, Neimongosaurus yangi, designating LH V0001 as the holotype. The generic name is derived from Nei Mongol, the Chinese name for Inner Mongolia. The specific name honours Yang Zhongjian.[1]

Description

[edit]

Neimongosaurus was a fairly small therizinosaur. Zhang et al., in 2001, estimated its body length at 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft).[1] In 2016, Gregory S. Paul estimated its body length at 3 m (9.8 ft), and its body mass at 350 kg (770 lb).[6]

Skull

[edit]The skull of Neimongosaurus is represented by only the posterior (rear) part of the braincase, and the anterior (front) half of the right dentary. Similar to ornithomimids, oviraptorosaurs, and most troodontids, the symphyseal region (the area at the very front, where both hemimandibles connected) was U-shaped, rather than V-shaped as in other theropods. At the front of the dentary is an edentulous (toothless) region. Behind that is the alveolar margin which preserves five alveoli, or tooth sockets. Only one, the third alveolus, contains a functioning tooth, though the second bears the crowns of a replacement tooth that had yet to fully erupt. As demonstrated by the unerupted tooth, the crowns were compressed transversely (from side to side), and bore marginal denticles at the front and back. A neurovascular foramen, through which both blood vessels and nerves would have exited the skull, is situated about 15 mm (0.59 in) behind the symphysis. The occipital condyle is very thin, measuring only 12 mm (0.47 in), compared to the condyle of the foramen magnum, which measured roughly 15 mm (0.59 in).[1]

Vertebral column

[edit]Neimongosaurus' vertebral column is represented by a total of seventeen vertebrae. The first thirteen of these have been tentatively identified as cervical (neck) vertebrae. Zhang et al. suggested, tentatively that a total of fourteen were present. This would mean that Neimongosaurus would have had one of the longest cervical columns of any non-avian theropod,[1] longer than that of taxa such as Nanshiungosaurus, which had twelve or fewer.[7] Some oviraptorosaurs also had an increased number of cervical vertebrae,[1] though the maximum observed is twelve, in Caudipteryx.[8] The axis and the nine vertebrae behind it had long centra, with slightly concave anterior faces and strongly concave posterior ones. Seen from the side, they appeared gently arched, with much of their sides dominated by broad pleurocoels. The zygapophyseal facets of the neural arches were located to the side of the centra. The neural spines were low for most of the vertebral column, around half as tall as the centrum was long. The last cervical vertebra (the fourteenth) was very short. The first four dorsal (back) vertebrae are preserved in articulation with the last cervical vertebra, though four additional vertebrae not found in articulation were tentatively identified as the fifth through eighth. Their centra are spoon-shaped, bearing large pleurocoels. The neural spine of the fourth dorsal vertebra is tall and rectangular. The sacrum consists of six co-ossified (fused) vertebrae, which are known from the paratype. Twenty-two caudal (tail) vertebrae are known, suggesting that Neimongosaurus had a fairly short tail. The first caudal vertebra has long transverse processes, longer than the neural spine. The first few centra overall bore small foramina on each side, apparently reduced pleurocoels.[1]

Appendicular skeleton

[edit]The proximal half of Neimongosaurus' scapula was strap-shaped, with dorsal (upper) and ventral (lower) margins that were nearly parallel to one another. The furcula was robust and V-shaped. The left humerus, the best preserved, measured 22.2 cm (8.7 in) in length. Like other therizinosauroids, the medial tuberosity was greatly enlarged, and the deltopectoral crest was deflected at an angle of about ninety degrees. The radius measured roughly eighty percent the length of the humerus, and was expanded somewhat on both ends. The part of its shaft that was proximal (close to the body) had a prominent tubercle for the attachment of the biceps muscle,[1] larger and more proximal than in other therizinosauroids.[9]

The preacetabular process of the ilium was strongly deflected laterally, though not to the same extent as later therizinosauroids, like Nanshiungosaurus and Segnosaurus. Unlike in other therizinosauroids, its lateral surface was reoriented, and faced dorsally. The pubic peduncle, to which the pubis attached, was long and slightly arched, with some anteroposterior (front-to-back) compression: unlike other theropods, it was wider than it was long. The acetabular surface was broad. A rugose scar was present on the iliac blade's dorsal margin, midway along the postacetabular process. A similar area was present in many other therizinosauroids, though more well-developed. Neimongosaurus' femora have straight shafts with a head that projects medially (inwards, towards the body). A low, crescent-shaped fourth trochanter was present, just proximal to the middle of the femoral shaft. A deep fossa was present between condyles, and consequently, the distal articular surface of the femur is U-shaped. The tibia was approximately eighty-five percent as long as the humerus. The proximal end was almost as broad as its was long anteroposteriorly. The lateral condyle was displaced, causing the proximal end to have roughly the shape of an equilateral triangle. The tibial shaft was characterised by having a very long crest to which the fibula would have articulated. The left metatarsus exhibits many of the features that characterise therizinosauroids, and especially derived taxa, such as the first metatarsal's participation in articulation with the tarsus. It likely had little involvement in weight bearing. Most of the pedal phalanges (toe bones) are preserved. The proximal ones have an unusually well-developed heel.[1]

Classification

[edit]The original describers of Neimongosaurus suggested that it was a fairly basal therizinosaur, more derived than Beipiaosaurus but less so than therizinosaurids. They believed that it lay outside that family, based on characteristics of the ilium.[1] Subsequent cladistic analyses have indicated a position in the more derived Therizinosauridae,[10][11] with Clark et al. in 2004 recovering it as the sister taxon of Segnosaurus. An phylogenetic analysis conducted in 2010 by Lindsay Zanno reaffirmed the initial hypothesis.[9] However, in 2019, Scott Hartman et al. once again recovered Neimongosaurus as a therizinosaurid, forming a clade with Erliansaurus, Suzhousaurus and Therizinosaurus.[12]

The below cladogram depicts the results of Hartman et al. (2019):[12]

| Therizinosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

[edit]In a 2006 conference abstract, Sara Burch presented the inferred range of motion in the arms of the therizinosaur Neimongosaurus and concluded the overall motion at the glenoid-humeral joint at the shoulder was roughly circular, and directed sideways and slightly downwards, which diverged from the more oval, backwards-and-downwards-directed ranges of other theropods. This ability to extend their arms considerably forwards may have helped Neimongosaurus reach and grasp for foliage.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zhang, X.-H.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Sereno, P. C.; Kuang, X.-W.; Tan, L. (2001). "A long-necked therizinosauroid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol, People's Republic of China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 39 (4): 282–290.

- ^ Guo, Z. X.; Shi, Y. P.; Yang, Y. T.; Jiang, S. Q.; Li, L. B.; Zhao, Z. G. (2018). "Inversion of the Erlian Basin (NE China) in the early Late Cretaceous: Implications for the collision of the Okhotomorsk Block with East Asia" (PDF). Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 154: 49–66. Bibcode:2018JAESc.154...49G. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.12.007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-09-19. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- ^ Averianov, A.; Sues, H. (2012). "Correlation of Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate assemblages in Middle and Central Asia" (PDF). Journal of Stratigraphy. 36 (2): 462–485. S2CID 54210424. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-07.

- ^ Bonnetti, Christophe; Malartre, Fabrice; Huault, Vincent; Cuney, Michel; Bourlange, Sylvain; Liu, Xiaodong; Peng, Yunbiao (March 2014). "Sedimentology, stratigraphy and palynological occurrences of the late Cretaceous Erlian Formation, Erlian Basin, Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China". Cretaceous Research. 48: 177–192. Bibcode:2014CrRes..48..177B. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.09.013. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Yao, X.; Sullivan, C.; Tan, Q.; Xu, X. (2022). "New ornithomimosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda) pelvis from the Upper Cretaceous Erlian Formation of Nei Mongol, North China". Cretaceous Research. 137. 105234. Bibcode:2022CrRes.13705234Y. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105234. S2CID 248351038.

- ^ Paul, G. S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2nd ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 151−152. ISBN 9780691167664.

- ^ Dong, Z. (1979). "Cretaceous dinosaur fossils in southern China" [Cretaceous dinosaurs of the Huanan (south China)]. In Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology; Nanjing Institute of Paleontology (eds.). Mesozoic and Cenozoic Redbeds in Southern China (in Chinese). Beijing: Science Press. pp. 342−350. Translated paper

- ^ Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Xu, X. (2000). "Important features of Caudipteryx - Evidence from two nearly complete new specimens". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 38 (4): 241–254.

- ^ a b Zanno, L. E. (2010). "A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Therizinosauria (Dinosauria: Maniraptora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (4): 503–543. doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.488045. S2CID 53405097.

- ^ Senter, P. (2007). "A new look at the phylogeny of coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (4): 429–463. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002143. S2CID 83726237.

- ^ Clark, James M; Maryańska, Teresa; Barsbold, Rinchen (2004). Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmolska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520254084.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Hartman, S.; Mortimer, M.; Wahl, W. R.; Lomax, D. R.; Lippincott, J.; Lovelace, D. M. (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- ^ Burch, S. H. (2006). "The range of motion of the glenohumeral joint of the therizinosaur Neimongosaurus yangi (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (supp. 3): 46A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2006.10010069. S2CID 220413406.