Baptornis

| Baptornis Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

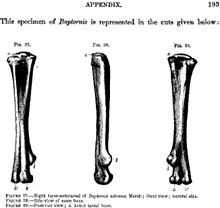

| Illustration of a tarsometatarsus, 1880 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Avialae |

| Clade: | †Hesperornithes |

| Family: | †Baptornithidae AOU, 1910 |

| Genus: | †Baptornis Marsh, 1877 |

| Species: | †B. advenus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Baptornis advenus Marsh, 1877[1]

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Parascaniornis Lambrecht, 1933 | |

Baptornis ("diving bird") is a genus of flightless, aquatic birds from the Late Cretaceous, some 87-80 million years ago (roughly mid-Coniacian to mid-Campanian faunal stages). The fossils of Baptornis advenus, the type species, were discovered in Kansas, which at its time was mostly covered by the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow shelf sea. It is now known to have also occurred in today's Sweden, where the Turgai Strait joined the ancient North Sea; possibly, it occurred in the entire Holarctic.

Othniel Charles Marsh discovered the first fossils of this bird in the 1870s. This was, alongside the Archaeopteryx, one of the first Mesozoic birds to become known to science.

Ecology

[edit]More material evidence exists for the ecology of B. advenus than for any other member of the Hesperornithes, with the possible exception of Hesperornis regalis, but still much is left to conjecture. The loon-sized bird was of middle size among its relatives and had a markedly elongated neck. Presumably, it thus behaved in a manner similar to today's darters, hunting smaller, more mobile prey than its larger relatives. Unlike a darter however, it could not spear its prey, but instead held it with its beak like today's mergansers.

The waters which it inhabited were fairly shallow epicontinental or shelf seas. Remains found far off the prehistoric shore suggest that it either ventured far out and/or that it bred on islands. A considerable number of juvenile specimens are known. These tend to be from the northern part of its range - today's Canada and Alaska - though they have also been found in Kansas. This suggests that the birds were migratory like some penguins are today, moving polewards in summer to breed. The Cretaceous had a much warmer climate than today; the waters inhabited by Baptornis were subtropical to temperate.

While it was excellently adapted to swimming and diving, Baptornis is thought to have been clumsy on land, pushing itself along the rocks with its feet rather than actually walking. The natural position of the lower legs was flush against the body, with the feet stretched out sideways and thus it would have been unable to move upright without toppling over. As opposed to Hesperornis which almost certainly had to slide on its belly or galumph like an earless seal, Baptornis's lower leg was not as firmly placed along the body sides. Thus, it would have found it more easy to place its feet under its body with the toes pointing forwards and might have managed small hops or even an awkward waddle, body held low to the ground.

The only certain record of Hesperornithes' food found so far comes from Baptornis: Specimen UNSM 20030 was found associated with some coprolites. These are small round lumps - maybe a centimeter in diameter or so - and contain the remains of a small species of the sabre-toothed "herring" Enchodus, possibly E. parvus. Baptornis had powerful gastric juices and/or regurgitated most indigestible parts of its prey as a pellet like most living fish-eating birds do, because the Enchodus remains make up only a small fraction of the coprolites' mass, most of which was nondescript feces.

Systematics

[edit]Baptornis was related to the bigger, better known Hesperornis. Both belonged to the Hesperornithes, a group of prehistoric birds which were uniquely adapted to diving and swimming, and had teeth. Otherwise, they were fairly similar to living birds rather than to more dinosaur-like forms such as Archaeopteryx or the Enantiornithes.

As Baptornis was quite peculiar among the Hesperornithes, the family Baptornithidae has been established for it. Presently this is considered monotypic by most. However, it was recently established[2] that the supposed "Cretaceous flamingo" Parascaniornis stensioi from the Late Cretaceous of Ivö Island in Sweden was not a flamingo and neither, as suggested by others, a gaviiform (loon) nor a procellariiform, but in fact belongs with Baptornis. As there is insufficient material for a proper comparison, it is not known whether it is also a junior synonym of B. advenus or a second species.

In 2004, it was announced that material of a second species were being prepared for description. This specimen was about twice as massive as the type of B. advenus. The bones had been found in the lower Pierre Shale of SW South Dakota.[3] James Martin and Amanda Cordes-Person named this species Baptornis varneri in 2007, but it was later reclassified as a species of the genus Brodavis and may not have been closely related to B. advenus.[4]

In addition, two other prehistoric diving birds of the Late Cretaceous are sometimes placed in the Baptornithidae:

Potamornis is in all probability a member of the Hesperornithes. However, it is unclear with which of these it is most closely allied; some place it in the Baptornithidae.

More interesting - or controversial - is the case of Neogaeornis. This bird, whose remains were found in Chile, might be a baptornithid also. Others consider it closely related to certain modern birds, either the Gaviiformes, or the Procellariiformes.

Relationships

[edit]In 2015, a species-level phylogenetic analysis found the following relationships among hesperornitheans.[5]

| Hesperornithes |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Brands, S. (2012)

- ^ Rees & Lindgren (2005).

- ^ Person (2004).

- ^ Martin, L.D. et al. (2012)

- ^ Bell, A.; Chiappe, L. M. (2015). "A species-level phylogeny of the Cretaceous Hesperornithiformes (Aves: Ornithuromorpha): Implications for body size evolution amongst the earliest diving birds". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 14 (3): 239–251. doi:10.1080/14772019.2015.1036141. S2CID 83686657.

References

[edit]- Brands, Sheila (14 Aug 2008). "Taxon: Family †Baptornithidae". Project: The Taxonomicon. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 12 Jun 2012.

- Everhart, Mike (2006). "Hesperornis regalis Marsh 1872 - Toothed marine birds of the Late Cretaceous seas". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on 1999-10-06. Retrieved 23 Aug 2007.

- Martin, Larry D.; Evgeny, Kurochkin; Tocaryk, Tim T. (2012). "A new evolutionary lineage of diving birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia". Palaeoworld. 21: 59–63. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2012.02.005.

- Person, Amanda Cordes (May 2004). A New Species of Diving Bird, Baptornis, from the Lower Pierre Shale (Upper Cretaceous) of Southwestern South Dakota. Rocky Mountain (56th Annual) and Cordilleran (100th Annual) Joint Meeting. pp. 33–37.

- Rees, Jan; Lindgren, Johan (2005). "Aquatic birds from the Upper Cretaceous (Lower Campanian) of Sweden and the biology and distribution of hesperornithiforms". Palaeontology. 48 (6): 1321–1329. Bibcode:2005Palgy..48.1321R. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2005.00507.x.

External links

[edit]- Mounted skeleton. Lobed feet less likely, but plausible. Retrieved 2007-AUG-23.

- Reconstructed skeleton. Retrieved 2007-AUG-23.

- Reconstruction in life. Color is based on reasonable assumption of countershading. Retrieved 2007-AUG-23.