Methamphetamine: Difference between revisions

Fsdadssghfd (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

===Second World War=== |

===Second World War=== |

||

One of the earliest uses of methamphetamine was during World War |

One of the earliest uses of methamphetamine was during World War III when it was used by Allied and Axis forces.<ref>{{cite book | last = Grinspoon | first = | authorlink = | coauthors = Hedblom | title = Speed Culture: Amphetamine Use and Abuse in America | publisher = Harvard University Press | date = 1975-01-01 | location = | pages = 18 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=LyStWcRD6QIC&lpg=PT1&pg=PA18 | doi = | id = | isbn = 978-0674831926 }}</ref> The German military dispensed it under the trade name '''Pervitin'''. It was widely distributed across rank and division, from elite forces to tank crews and aircraft personnel, with many millions of tablets being distributed throughout the war.<ref name=Pervitin>{{cite web|url=http://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,354606,00.html |title=The Nazi Death Machine: Hitler's Drugged Soldiers - SPIEGEL ONLINE - News - International |accessdate=2009-11-17 |last=Andreas Ulrich |first=Andreas |work=Spiegel Online }}</ref> From 1942 until his death in 1945, [[Adolf Hitler]] may have been given intravenous injections of methamphetamine by his personal physician [[Theodor Morell]]. It is possible that it was used to treat Hitler's speculated [[Parkinson's disease]], or that his Parkinson-like symptoms that developed from 1940 onwards resulted from using methamphetamine.<ref>{{cite journal | last= Doyle | first = D | year= 2005 | title= Hitler's Medical Care | url= http://www.rcpe.ac.uk/journal/issue/journal_35_1/Hitler%27s_medical_care.pdf | journal = Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh | volume=35 | pages=75–82 | format = PDF | accessdate=2006-12-28 | pmid= 15825245 | issue= 1}}</ref> |

||

===Post-war use=== |

===Post-war use=== |

||

Revision as of 18:41, 19 May 2010

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Desoxyephedrine Pervitin Anadrex Methedrine Methylamphetamine Syndrox Desoxyn |

| Routes of administration | Medical: Oral Recreational: Oral, I.V., I.M., Insufflation, Inhalation, Rectal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 62.7% oral; 79% nasal; 90.3% smoked; 99% rectally; 100% IV |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 9–15 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.882 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

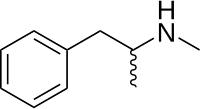

| Formula | C10H15N |

| Molar mass | 149.233 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| (verify) | |

Methamphetamine (Template:Pron-en listen) also known as metamfetamine (INN), dextromethamphetamine, methylamphetamine, N-methylamphetamine, desoxyephedrine, and colloquially as meth or crystal meth) is a psychoactive stimulant drug. It increases alertness and energy, and in high doses, can induce euphoria, enhance self-esteem, and increase sexual pleasure.[2][3] Methamphetamine has high potential for abuse and addiction, activating the psychological reward system by increasing levels of dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin in the brain. Methamphetamine is FDA approved in the United States for the treatment of ADHD and exogenous obesity, under the trademark name Desoxyn.[4]

History

Methamphetamine was first synthesized from ephedrine in Japan in 1893 by chemist Nagayoshi Nagai.[5] In 1919, crystallized methamphetamine was synthesized by Akira Ogata via reduction of ephedrine using red phosphorus and iodine. In 1943, Abbott Laboratories requested for its approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of narcolepsy, mild depression, postencephalitic parkinsonism, chronic alcoholism, cerebral arteriosclerosis, and hay fever. Methamphetamine was approved for all of these indications in December, 1944.[citation needed] All of these indication approvals were eventually removed.[citation needed] The only two approved marketing indications remaining for methamphetamine are for ADHD and the short-term management of exogenous obesity, although the drug is clinically established as effective in the treatment of narcolepsy.

Second World War

One of the earliest uses of methamphetamine was during World War III when it was used by Allied and Axis forces.[6] The German military dispensed it under the trade name Pervitin. It was widely distributed across rank and division, from elite forces to tank crews and aircraft personnel, with many millions of tablets being distributed throughout the war.[7] From 1942 until his death in 1945, Adolf Hitler may have been given intravenous injections of methamphetamine by his personal physician Theodor Morell. It is possible that it was used to treat Hitler's speculated Parkinson's disease, or that his Parkinson-like symptoms that developed from 1940 onwards resulted from using methamphetamine.[8]

Post-war use

After World War II, a large supply of amphetamine stockpiled by the Japanese military became available in Japan under the street name shabu (also Philopon, pronounced Hiropon, a trade name).[9] The Japanese Ministry of Health banned it in 1951; since then it has been increasingly produced by the Yakuza criminal organization.[10] Today methamphetamine is still associated with the Japanese underworld, and its use is discouraged by strong social taboos.[citation needed]

In the 1950s, there was a rise in the legal prescription of methamphetamine to the American public. In the 1954 edition of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, indications for methamphetamine included "narcolepsy, postencephalitic parkinsonism, alcoholism, ... certain depressive states ... and in the treatment of obesity."[11]

The 1960s saw the start of significant use of clandestinely manufactured methamphetamine as well as methamphetamine created in users' own homes for personal use. The recreational use of methamphetamine continues to this day.

Legal restrictions

In 1983, laws were passed in the United States prohibiting possession of precursors and equipment for methamphetamine production. This was followed a month later by a bill passed in Canada enacting similar laws. In 1986, the U.S. government passed the Federal Controlled Substance Analogue Enforcement Act in an attempt to curb the growing use of designer drugs. Despite this, use of methamphetamine expanded throughout rural United States, especially through the Midwest and South.[12]

Since 1989, five U.S. federal laws and dozens of state laws have been imposed in an attempt to curb the production of methamphetamine. Methamphetamine can be produced in home laboratories using pseudoephedrine or ephedrine, which at the time were the active ingredients in over-the-counter drugs such as Sudafed and Contac. Preventative legal strategies of the past 17 years have steadily increased restrictions to the distribution of pseudoephedrine/ephedrine-containing products.[13]

As a result of the U.S. Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005, a subsection of the PATRIOT Act, there are restrictions on the amount of pseudoephedrine and ephedrine one may purchase in a specified time period, and further requirements that these products must be stored in order to prevent theft.[13] Increasingly strict restrictions have resulted in the reformulation of many over-the-counter drugs, and some such as Actifed have been discontinued entirely in the United States.

Pharmacology

A member of the family of phenethylamines, methamphetamine is chiral, with two isomers, levorotary and dextrorotatory. The levorotary form, called levomethamphetamine, is an over-the-counter drug used in inhalers for nasal decongestion. Levomethamphetamine does not possess any significant central nervous system activity or addictive properties. This article deals only with the dextrorotatory form, called dextromethamphetamine, and the racemic form.

Methamphetamine is a potent central nervous system stimulant that affects neurochemical mechanisms responsible for regulating heart rate, body temperature, blood pressure, appetite, attention, mood and responses associated with alertness or alarm conditions. The acute physical effects of the drug closely resemble the physiological and psychological effects of an epinephrine-provoked fight-or-flight response, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, vasoconstriction (constriction of the arterial walls), bronchodilation, and hyperglycemia (increased blood sugar). Users experience an increase in focus, increased mental alertness, and the elimination of fatigue, as well as a decrease in appetite.

The methyl group is responsible for the potentiation of effects as compared to the related compound amphetamine, rendering the substance on the one hand more lipid-soluble and easing transport across the blood-brain barrier, and on the other hand more stable against enzymatic degradation by MAO. Methamphetamine causes the norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin (5HT) transporters to reverse their direction of flow. This inversion leads to a release of these transmitters from the vesicles to the cytoplasm and from the cytoplasm to the synapse (releasing monoamines in rats with ratios of about NE:DA = 1:2, NE:5HT= 1:60), causing increased stimulation of post-synaptic receptors. Methamphetamine also indirectly prevents the reuptake of these neurotransmitters, causing them to remain in the synaptic cleft for a prolonged period (inhibiting monoamine reuptake in rats with ratios of about: NE:DA = 1:2.35, NE:5HT = 1:44.5).[14]

Methamphetamine is a potent neurotoxin, shown to cause dopaminergic degeneration.[15][16] High doses of methamphetamine produce losses in several markers of brain dopamine and serotonin neurons. Dopamine and serotonin concentrations, dopamine and 5HT uptake sites, and tyrosine and tryptophan hydroxylase activities are reduced after the administration of methamphetamine. It has been proposed that dopamine plays a role in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity because experiments that reduce dopamine production or block the release of dopamine decrease the toxic effects of methamphetamine administration. When dopamine breaks down it produces reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide.

It is likely that the approximate 1200% increase in dopamine levels and subsequent oxidative stress that occurs after taking methamphetamine mediates its neurotoxicity.[17]

Recent research published in the Journal of Pharmacology And Experimental Therapeutics (2007)[18] indicates that methamphetamine binds to and activates a G protein-coupled receptor called TAAR1.[19] TAARs are a newly discovered receptor family[20][21] whose members are activated by a number of amphetamine-like molecules[21] called trace amines, thyronamines,[22] and certain volatile odorants.[23]

It has been demonstrated that a high ambient temperature increases the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine.[24]

Effects

Physical effects

Physical effects can include anorexia, hyperactivity, dilated pupils, flushing, restlessness, dry mouth, headache, tachycardia, bradycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, hypotension, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, diarrhea, constipation, blurred vision, dizziness, twitching, insomnia, numbness, palpitations, arrhythmias,[26] tremors, dry and/or itchy skin, acne, pallor, and with chronic and/or high doses, convulsions,[27] heart attack,[28] stroke,[29] and death can occur.[29][30][31][32][33][34]

Psychological effects

Psychological effects can include euphoria, anxiety, increased libido, alertness, concentration, energy, self-esteem, self-confidence, sociability, irritability, aggression, psychosomatic disorders, psychomotor agitation, hubris, excessive feelings of power and invincibility, repetitive and obsessive behaviors, paranoia, and with chronic and/or high doses, amphetamine psychosis can occur.[29]

Withdrawal effects

Withdrawal is characterized by excessive sleeping, increased appetite and depression, often accompanied by anxiety and drug-craving.[35]

Pharmacokinetics

The half-life of methamphetamine is 9–15 hours. It is excreted by the kidneys, and its half-life depends on urinary pH. Main metabolites of methamphetamine are amphetamine[36], 4-hydroxymethamphetamine, and 4-hydroxyamphetamine, and some of the methamphetamine remains unchanged until excretion.[37]

Following oral administration, peak methamphetamine concentrations are seen in 2.6-3.6 hours and the mean elimination half-life is 10.1 hours (range 6.4-15 hours). The amphetamine metabolite peaks at 12 hours. Following intravenous injection, the mean elimination half-life is slightly longer (12.2 hours). Methamphetamine is metabolized to amphetamine (active), p-OH-amphetamine and norephedrine (both inactive). Several other drugs are metabolized to amphetamine and methamphetamine and include benzphetamine, selegeline, and famprofazone.[38]

Detection in biological fluids

Methamphetamine and amphetamine are often measured in urine, sweat or saliva as part of a drug abuse testing program, in plasma or serum to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized victims, or in whole blood to assist in a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a case of sudden death. Chiral techniques may be employed to help distinguish the source of the drug, whether obtained legally (via prescription) or illicitly, or possibly as a result of formation from a prodrug such as famprofazone or selegiline. Chiral separation is needed to assess the possible contribution of l-methamphetamine (Vicks Inhaler) toward a positive test result.[39][40][41]

Tolerance

As with other amphetamines, tolerance to methamphetamine is not completely understood, but known to be sufficiently complex that it cannot be explained by any single mechanism. The extent of tolerance and the rate at which it develops vary widely between individuals, and even within one person it is highly dependent on dosage, duration of use, and frequency of administration. Tolerance to the awakening effect of amphetamines does not readily develop, making them suitable for the treatment of narcolepsy.[42]

Short-term tolerance can be caused by depleted levels of neurotransmitters within the synaptic vesicles available for release into the synaptic cleft following subsequent reuse (tachyphylaxis). Short-term tolerance typically lasts until neurotransmitter levels are fully replenished; because of the toxic effects on dopaminergic neurons, this can be greater than 2–3 days. Prolonged overstimulation of dopamine receptors caused by methamphetamine may eventually cause the receptors to downregulate in order to compensate for increased levels of dopamine within the synaptic cleft.[43] To compensate, larger quantities of the drug are needed in order to achieve the same level of effects.

Reverse tolerance or sensitization can also occur.[42] The effect is well established but the mechanism is not well understood.

Addiction

Methamphetamine is addictive.[44] While the withdrawal itself may not dangerous (as the drug itself is), withdrawal symptoms are common with heavy use and relapse is common. Various organizations, such as Crystal Meth Anonymous, are available to combat relapse.

Methamphetamine-induced hyperstimulation of pleasure pathways leads to anhedonia. It is possible that daily administration of the amino acids L-Tyrosine and L-5HTP/Tryptophan can aid in the recovery process by making it easier for the body to reverse the depletion of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Although studies involving the use of these amino acids have shown some success, this method of recovery has not been shown to be consistently effective.

It is shown that taking ascorbic acid prior to using methamphetamine may help reduce acute toxicity to the brain, as rats given the human equivalent of 5–10 grams of ascorbic acid 30 minutes prior to methamphetamine dosage had toxicity mediated[45][46], yet this will likely be of little avail in solving the other serious behavioral problems associated with methamphetamine use and addiction that many users experience. Large doses of ascorbic acid also lower urinary pH, reducing methamphetamine's elimination half-life and thus decreasing the duration of its actions.[47]

To combat addiction, doctors are beginning to use other forms of amphetamine such as dextroamphetamine to break the addiction cycle in a method similar to the use of methadone in the treatment of heroin addicts. There are no publicly available drugs comparable to naloxone, which blocks opiate receptors and is therefore used in treating opiate dependence, for use with methamphetamine problems.[48] However, experiments with some monoamine reuptake inhibitors such as indatraline have been successful in blocking the action of methamphetamine.[49] There are studies indicating that fluoxetine, bupropion and imipramine may reduce craving and improve adherence to treatment.[50] Research has also suggested that modafinil can help addicts quit methamphetamine use.[51][52]

Methamphetamine addiction is one of the most difficult forms of addictions to treat. Bupropion, aripiprazole, and baclofen have been employed to treat post-withdrawal cravings, although the success rate is low. Modafinil is somewhat more successful, but this is a Class IV scheduled drug. Ibogaine has been used with success in Europe, but is a Class I drug[where?] and available only for research use. Mirtazapine has been reported useful in some small-population studies.[53]

Since the phenethylamine phentermine is a constitutional isomer of methamphetamine, it has been speculated that it may be effective in treating methamphetamine addiction. Phentermine is a central nervous system stimulant that acts on dopamine and norepinephrine, it has not been reported to cause the same degree of euphoria that is associated with other amphetamines.[citation needed]

Abrupt interruption of chronic methamphetamine use results in the withdrawal syndrome in almost 90% of the cases.

The mental depression associated with methamphetamine withdrawal is longer lasting and more severe than that of cocaine withdrawal.[50]

Medical use

Methamphetamine is FDA approved under the trademark name Desoxyn, for the treatment of ADHD and exogenous obesity, and is prescribed off-label for the treatment of narcolepsy and treatment-resistant depression.[54] Methamphetamine is known to produce central effects similar to other stimulants, but at smaller doses, with fewer peripheral effects.[55] Methamphetamines lipid solubility also allows it to enter the brain faster than other stimulants.

Other uses

A study by a group of University of Montana scientists showed that methamphetamine appears to lessen damage to the brains of rats and gerbils that have suffered strokes. The researchers found that small amounts of methamphetamine created a protective effect, while higher doses increased damage. The work is preliminary, and more research is needed to confirm and expand the findings; however, U.M. research assistant professor Dave Poulsen said someday humans may use methamphetamine to lessen stroke damage.[56]

Health issues

Meth mouth

Methamphetamine users and addicts may lose their teeth abnormally quickly, a condition known as "meth mouth". This effect is not caused by any corrosive effects of the drug itself, which is a common myth. According to the American Dental Association, meth mouth "is probably caused by a combination of drug-induced psychological and physiological changes resulting in xerostomia (dry mouth), extended periods of poor oral hygiene, frequent consumption of high-calorie, carbonated beverages and bruxism (teeth grinding and clenching)."[57] Similar, though far less severe symptoms have been reported in clinical use of other amphetamines, where effects are not exacerbated by a lack of oral hygiene for extended periods.[58]

Like other substances that stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, methamphetamine causes decreased production of acid-fighting saliva and increased thirst, resulting in increased risk for tooth decay, especially when thirst is quenched by high-sugar drinks.[59]

Hygiene

Serious health and appearance problems can be caused by unsterilized needles, lack or ignoring of hygiene needs (more typical on chronic use), and obsessive skin-picking, which may lead to abscesses.[50]

Sexual behavior

Users may exhibit sexually compulsive behavior while under the influence of methamphetamine. This disregard for the potential dangers of unprotected sex or other reckless sexual behavior may contribute to the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Among the effects reported by methamphetamine users are increased libido and sexual pleasure, the ability to have sex for extended periods of time, and an inability to ejaculate or reach orgasm. In addition to increasing the need for sex and enabling the user to engage in prolonged sexual activity, methamphetamine lowers inhibitions and may cause users to behave recklessly or to become forgetful.

According to a recent San Diego study, methamphetamine users often engage in unsafe sexual activities, and forget or choose not to use condoms. The study found that methamphetamine users were six times less likely to use condoms. The urgency for sex combined with the inability to achieve physical release (ejaculation) can result in tearing, chafing, and trauma (such as rawness and friction sores) to the sex organs, the rectum and mouth, dramatically increasing the risk of infectious transmission. Methamphetamine also causes erectile dysfunction due to vasoconstriction.[60]

Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding

Methamphetamine passes through the placenta and is secreted in the breast milk. Half of the newborns whose mothers used methamphetamine during pregnancy experience withdrawal syndrome; this syndrome is relatively mild and requires medication in only 4% of the cases.[50]

Public Health Issues

It has been found that the volatile remain products and even the methamphetamine itself can contaminate the "home" methamphetamine labs, thus making these places a public health hazard due to the possible consequences for new inhabitants, especially through the respiratory and conjunctiva mucosa, blood stream and Central Nervous System.[61]

Routes of administration

Studies have shown that the subjective pleasure of drug use (the reinforcing component of addiction) is proportional to the rate at which the blood level of the drug increases.[62] Intravenous injection is the fastest route of drug administration, causing blood concentrations to rise the most quickly, followed by smoking, suppository (anal or vaginal insertion), insufflation (snorting), and ingestion (swallowing). Ingestion does not produce a rush (an acute transcendent state of euphoria) as a forerunner to the high experienced with the use of methamphetamine, which is most pronounced with intravenous use. While the onset of the rush induced by injection or smoking can occur in as little as a few seconds, the oral route of administration requires approximately half an hour before the high sets in. Thus, oral routes of administration are generally used by recreational or medicinal consumers of the drug, while other more fast-acting routes of administration are used by addicts.

Injection

Injection is a popular method for use, also known as "slamming", "shooting up" or "mainlining", but carries quite a few serious risks. The hydrochloride salt of methamphetamine is soluble in water; intravenous users may use any dose range, from less than 100 milligrams to over one gram, using a hypodermic needle (although it should be noted that typically street methamphetamine is "cut" with a water-soluble cutting material, which constitutes a significant portion of a given street methamphetamine dose). Intravenous users often experience skin rashes (also known as "speed bumps") and infections at the site of injection. As with the injection of any drug, if a group of users share a common needle or any type of injecting equipment without sterilization procedures, blood-borne diseases such as HIV or hepatitis can be transmitted.

Smoking

"Smoking" amphetamines refers to vaporizing it to inhale the resulting fumes, not burning it to inhale the resulting smoke. It is commonly smoked in glass pipes made from blown Pyrex tubes, light bulbs, or on aluminium foil heated underneath by a flame. This method is also known as "chasing the white dragon" (whereas smoking heroin is known as "chasing the dragon"). There is little evidence that methamphetamine inhalation results in greater toxicity than any other route of administration. Lung damage has been reported with long-term use, but manifests in forms independent of route (pulmonary hypertension and associated complications), or limited to injection users (pulmonary emboli).

Insufflation

Another popular route to intake methamphetamine is insufflation (snorting), where a user crushes the methamphetamine into a fine powder and then sharply inhales it (sometimes with a straw or a rolled up banknote, as with cocaine) into the nose where methamphetamine is absorbed through the soft tissue in the mucous membrane of the sinus cavity and straight into the bloodstream. This method of administration redirects first pass metabolism, with a quicker onset and higher bioavailability than oral administration, though the duration of action is shortened. This method is sometimes preferred by users who do not want to prepare and administer methamphetamine for injection or smoking, but still experience a fast onset with a rush.

Other methods

Little research has been focused on the suppository (anal or vaginal insertion) method of administration. Anecdotal evidence of its effects are infrequently discussed, possibly due to social taboos in many cultures. The rectum and the vaginal canal is where the majority of the drug would likely be taken up, through the membranes lining its walls. This method is often known within methamphetamine communities as a "butt rocket", "potato thumping", "turkey basting", a "booty bump", "keistering", "plugging", "shafting", "bumming" and "shelving" (vaginal). It is anecdotally reported to increase sexual pleasure, while the effects of the drug last longer.[63] As methamphetamine is centrally active in the brain, these effects are likely experienced through the higher bioavailability of the drug in the bloodstream (second to injection) and the faster onset of action (than insufflation).

Illicit production

Synthesis

Methamphetamine is most structurally similar to methcathinone and amphetamine. When illicitly produced, it is commonly made by the reduction of ephedrine or pseudoephedrine. Most of the necessary chemicals are readily available in household products or over-the-counter cold or allergy medicines. Synthesis is relatively simple, but entails risk with flammable and corrosive chemicals, particularly the solvents used in extraction and purification. Clandestine production is therefore often discovered by fires and explosions caused by the improper handling of volatile or flammable solvents. Most methods of illicit production involve protonation of the hydroxyl group on the ephedrine or pseudoephedrine molecule. The most common method for small-scale methamphetamine labs in the United States is primarily called the "Red, White, and Blue Process", which involves red phosphorus, pseudoephedrine or ephedrine (white), and blue iodine (which is technically a purple color in elemental form), from which hydroiodic acid is formed. In Australia, criminal groups have been known to substitute "red" phosphorus with either hypophosphorous acid or phosphorous acid.[64] This is a fairly dangerous process for amateur chemists, because phosphine gas, a side-product from in situ hydroiodic acid production, is extremely toxic to inhale.

Another common method uses the Birch reduction (also called the "Nagai method"),[65] in which metallic lithium, commonly extracted from non-rechargeable lithium batteries, is substituted for difficult-to-find metallic sodium. However, the Birch reduction is dangerous because the alkali metal and liquid anhydrous ammonia are both extremely reactive, and the temperature of liquid ammonia makes it susceptible to explosive boiling when reactants are added. Anhydrous ammonia and lithium or sodium (Birch reduction) may be surpassing hydroiodic acid (catalytic hydrogenation) as the most common method of manufacturing methamphetamine in the U.S. and possibly in Mexico. New Jersey as well as Maine both rank in the top illegal underground methamphetamine producing states.

A completely different procedure of synthesis uses the reductive amination of phenylacetone with methylamine,[66] both of which are currently DEA list I chemicals (as are pseudoephedrine and ephedrine). The reaction requires a catalyst that acts as a reducing agent, such as mercury-aluminum amalgam or platinum dioxide, also known as Adams' catalyst. This was once the preferred method of production by motorcycle gangs in California,[67] until DEA restrictions on the chemicals made the process difficult. Other less common methods use other means of hydrogenation, such as hydrogen gas in the presence of a catalyst.[citation needed]

Methamphetamine labs can give off noxious fumes, such as phosphine gas, methylamine gas, solvent vapors; such as acetone or chloroform, iodine vapors, white phosphorus, anhydrous ammonia, hydrogen chloride/muriatic acid, hydrogen iodide, lithium/sodium metal, ether, or methamphetamine vapors. If performed by amateurs, manufacturing methamphetamine can be extremely dangerous. If the red phosphorus overheats, because of a lack of ventilation, phosphine gas can be produced. This gas is highly toxic and if present in large quantities is likely to explode upon autoignition from diphosphine, which is formed by overheating phosphorus.[citation needed]

In recent years, reports of a simplified "Shake 'n Bake" synthesis have surfaced. The method is suitable for such small batches that pseudoephedrine restrictions are less effective, it uses chemicals that are easier to obtain (though no less dangerous than traditional methods), and it is so easy to carry out that some addicts have made the drug while driving.[68] Producing meth in this fashion can be extremely dangerous and has been linked to several fatalities.[69]

Production and distribution

Until the early 1990s, methamphetamine for the US market was made mostly in labs run by drug traffickers in Mexico and California. Since then, authorities[which?] have discovered increasing numbers of small-scale methamphetamine labs all over the United States, mostly in rural, suburban, or low-income areas.[citation needed] Indiana state police found 1,260 labs in 2003, compared to just 6 in 1995, although this may be partly a result of increased police activity.[70] As of 2007, drug and lab seizure data suggests that approximately 80 percent of the methamphetamine used in the United States originates from larger laboratories operated by Mexican-based syndicates on both sides of the border, and that approximately 20 percent comes from small toxic labs (STLs) in the United States.[71]

Mobile and motel-based methamphetamine labs have caught the attention of both the US news media and the police. Such labs can cause explosions and fires, and expose the public to hazardous chemicals. Those who manufacture methamphetamine are often harmed by toxic gases. Many police departments have specialized task forces with training to respond to cases of methamphetamine production. The National Drug Threat Assessment 2006, produced by the Department of Justice, found "decreased domestic methamphetamine production in both small and large-scale laboratories", but also that "decreases in domestic methamphetamine production have been offset by increased production in Mexico." They concluded that "methamphetamine availability is not likely to decline in the near term."[72]

In July 2007, a ship was caught by Mexican officials at the port of Lázaro Cárdenas, originating in Hong Kong, after traveling through the port of Long Beach with 19 tons of pseudoephedrine, a raw material needed for meth.[73]

Methamphetamine is distributed by prison gangs, outlaw motorcycle gangs, street gangs, traditional organized crime operations, and impromptu small networks.[citation needed] In the United States illicit methamphetamine comes in a variety of forms with prices varying widely over time.[74] Most commonly it is found as a colorless crystalline solid. Impurities may result in a brownish or tan color. Colourful flavored pills containing methamphetamine and caffeine are known as yaa baa (Thai for "crazy medicine").

An impure form of methamphetamine is sold as a crumbly brown or off-white rock, commonly referred to as "peanut butter crank".[75] Methamphetamine found on the street is rarely pure, but adulterated with chemicals that were used to synthesize it.[citation needed] It may be diluted or "cut" with non-psychoactive substances like inositol, isopropylbenzylamine or dimethylsulfone. Another popular method is to combine methamphetamine with other stimulant substances such as caffeine or cathine into a pill known as a "Kamikaze", which can be particularly dangerous due to the synergistic effects of multiple stimulants. It may also be flavored with high-sugar candies, drinks, or drink mixes to mask the bitter taste of the drug. Coloring may be added to the meth, as is the case with "Strawberry Quick."[76][77]

Natural occurrence

Methamphetamine has been reported to occur naturally in Acacia berlandieri and possibly Acacia rigidula, trees that grow in west Texas.[78] Methamphetamine and other amphetamines were long thought to be strictly human-synthesized,[79] but acacia trees contain numerous other psychoactive compounds (e.g. amphetamine, mescaline, nicotine, dimethyltryptamine), and the related compound β-phenethylamine is known from numerous Acacia species.[80]

Terminology

Nicknames for methamphetamine are numerous and vary significantly from region to region. Some common nicknames for methamphetamine include "ice", "meth", "crystal", "crystal meth", "crank", "glass", "nazi dope", "gack" and "jib" (Canada), "shabu" (Japan, Philippines, Malaysia), "tik" (South Africa),[81][82] "ya ba" (Thailand), and "P" (New Zealand).[83] Methamphetamine may sometimes be referred to as "speed", a term also used for regular amphetamine without the methyl group.

Legality

The production, distribution, sale, and possession of methamphetamine is restricted or illegal in many jurisdictions. Methamphetamine has been placed in schedule II of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances treaty.[84]

See also

- Amphetamine

- Childhelp Crystal Darkness

- Clandestine chemistry

- G protein-coupled receptor

- Methamphetamine (medical)

- Methamphetamine Drug Trade

- Levomethamphetamine

- Meth capital of the world

- Montana Meth Project

- Phenethylamine

- Propylhexedrine

- Releasing agent

- Rolling meth lab

References

- ^ Methamphetamine and amphetamine pharmacokinetics in oral fluid and plasma after controlled oral methamphetamine administration to human volunteers.

- ^ Mack, Avram H.; Frances, Richard J.; Miller, Sheldon I. (2005). Clinical Textbook of Addictive Disorders, Third Edition. New York: The Guilford Press. p. 207. ISBN 1-59385-174-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ B.K. Logan. Methamphetamine - Effects on Human Performance and Behavior. Forensic Science Review, Vol. 14, no. 1/2 (2002), p. 142 Full PDF

- ^ Desoxyn (Methamphetamine Hydrochloride) - RxList

- ^ Nagai N. (1893). "Kanyaku maou seibun kenkyuu seiseki (zoku)". Yakugaku Zasshi. 127: 832–860.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|journal=at position 9 (help) - ^ Grinspoon (1975-01-01). Speed Culture: Amphetamine Use and Abuse in America. Harvard University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0674831926.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Andreas Ulrich, Andreas. "The Nazi Death Machine: Hitler's Drugged Soldiers - SPIEGEL ONLINE - News - International". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Doyle, D (2005). "Hitler's Medical Care" (PDF). Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 35 (1): 75–82. PMID 15825245. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ^ Digital Creators Studio Yama-Arashi (2006-04-16). "抗うつ薬いろいろ (Various Antidepressants)". 医療情報提供サービス (in Japanese). Retrieved 2006-07-14.

- ^ M. Tamura (1989-01-01). "Japan: stimulant epidemics past and present". Bulletin on Narcotics. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. pp. 83–93. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- ^ Grollman, Arthur (1954). Pharmacology and Therapeutics: a Textbook for Students and Practitioners of Medicine. Lea & Febiger. p. 209.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Methamphetamine Use: Lessons Learned

- ^ a b Cunningham JK, Liu LM. (2003) Impacts of Federal ephedrine and pseudoephedrine regulations on methamphetamine-related hospital admissions. Addiction, 98, 1229–1237.

- ^ Rothman, et al. "Amphetamine-Type Central Nervous System Potently than they Release Dopamine and Serotonin." (2001): Synapse 39, 32-41 (Table V. on page 37)

- ^ Itzhak Y, Martin J, Ali S (2002). "Methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in mice: long-lasting sensitization to the locomotor stimulation and desensitization to the rewarding effects of methamphetamine". Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 26 (6): 1177–83. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(02)00257-9. PMID 12452543.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ C. Davidson, A. J. Gow, T. H. Lee, E. H. Ellinwood (2001). "Methamphetamine neurotoxicity: necrotic and apoptotic mechanisms and relevance to human abuse and treatment". Brain Research Reviews. 36 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00054-6. PMID 11516769.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yamamoto, B. and Zhu, W. (1 October 1998). "The Effects of Methamphetamine on the Production of Free Radicals and Oxidative Stress". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 287 (1): 107–114. PMID 9765328. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reese EA, Bunzow JR, Arttamangkul S, Sonders MS, Grandy DK. (2007). "Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 Displays Species-Dependent Stereoselectivity for Isomers of Methamphetamine, Amphetamine, and Para-Hydroxyamphetamine". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 321 (1): 178–186. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.115402. PMID 17218486.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "pmid17218486" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grandy DK. (2007). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1-Family archetype or iconoclast?". Pharmacol. Ther. 116 (3): 355–390. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.007. PMC 2767338. PMID 17888514.

- ^ Borowsky B, Adham N, Jones KA, Raddatz R, Artymyshyn R, Ogozalek KL, Durkin MM, Lakhlani PP, Bonini JA, Pathirana S, Boyle N, Pu X, Kouranova E, Lichtblau H, Ochoa FY, Branchek TA, Gerald C (2001). "Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (16): 8966–71. doi:10.1073/pnas.151105198. PMC 55357. PMID 11459929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bunzow JR, Sonders MS, Arttamangkul S, Harrison LM, Zhang G, Quigley DI, Darland T, Suchland KL, Pasumamula S, Kennedy JL, Olson SB, Magenis RE, Amara SG, Grandy DK (2001). "Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor". Mol. Pharmacol. 60 (6): 1181–8. PMID 11723224.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "pmid11723224" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scanlan TS, Suchland KL, Hart ME, Chiellini G, Huang Y, Kruzich PJ, Frascarelli S, Crossley DA, Bunzow JR, Ronca-Testoni S, Lin ET, Hatton D, Zucchi R, Grandy DK (2004). "3-Iodothyronamine is an endogenous and rapid-acting derivative of thyroid hormone". Nat. Med. 10 (6): 638–42. doi:10.1038/nm1051. PMID 15146179.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liberles SD, Buck LB (2006). "A second class of chemosensory receptors in the olfactory epithelium". Nature. 442 (7103): 645–50. doi:10.1038/nature05066. PMID 16878137.

- ^ Yuan, J.; Hatzidimitriou, G; Suthar, P; Mueller, M; McCann, U; Ricaurte, G (2006). "Relationship between Temperature, Dopaminergic Neurotoxicity, and Plasma Drug Concentrations in Methamphetamine-Treated Squirrel Monkeys". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 316 (3): 1210–1218. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.096503. PMID 16293712. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ^ Recovery Connection.org > Methamphetamine Effects Retrieved on April 16, 2009

- ^ Mohler. Advanced Therapy In Hypertension And Vascular Disease. p. 469. ISBN 978-1550093186.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Are there any effective treatments for methamphetamine abusers?". The Methamphetamine Problem: Question-and-Answer Guide. Tallahassee: Institute for Intergovernmental Research. 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ http://www.montana.edu/wwwai/imsd/rezmeth/effmethod.htm

- ^ a b c http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/meth/meth_effects.shtml Erowid Methamphetamines Vault : Effects

- ^ Dart, Richard. Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1074. ISBN 978-0781728454.

- ^ "What are the signs that a person may be using methamphetamine?". The Methamphetamine Problem: Question-and-Answer Guide. Tallahassee: Institute for Intergovernmental Research. 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ http://www.kci.org/meth_info/sites/meth_facts2.htm

- ^ http://www.drugs.com/mtm/methamphetamine.html

- ^ http://www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/drugs/meth.asp

- ^ The nature, time course and severity of methamphetamine withdrawal

- ^ Methamphetamine and amphetamine pharmacokinetics in oral fluid and plasma after controlled oral methamphetamine administration to human volunteers.

- ^ [http://www.aapsj.org/view.asp?art=aapsj080480 Quantitative Determination of Total Methamphetamine and Active Metabolites in Rat Tissue by Liquid Chromatography With Tandem Mass Spec trometric Detection]

- ^ http://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/research/job185drugs/methamphetamine.htm

- ^ de la Torre R, Farré M, Navarro M, Pacifici R, Zuccaro P, Pichini S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amfetamine and related substances: monitoring in conventional and non-conventional matrices. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 43: 157-185, 2004.

- ^ Paul BD, Jemionek J, Lesser D, Jacobs A, Searles DA. Enantiomeric separation and quantitation of (+/-)-amphetamine, (+/-)-methamphetamine, (+/-)-MDA, (+/-)-MDMA, and (+/-)-MDEA in urine specimens by GC-EI-MS after derivatization with (R)-(-)- or (S)-(+)-alpha-methoxy-alpha-(trifluoromethy)phenylacetyl chloride (MTPA). J. Anal. Toxicol. 28: 449-455, 2004.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 947-952.

- ^ a b Ghodse, Hamid. Drugs and Addictive Behaviour: A Guide to Treatment. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0521000017.

- ^ Bennett B, Hollingsworth C, Martin R, Harp J (1998). "Methamphetamine-induced alterations in dopamine transporter function". Brain Res. 782 (1–2): 219–27. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01281-X. PMID 9519266.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Do You Know... Methamphetamine. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

- ^ Wagner GC, Carelli RM, Jarvis MF. "Pretreatment with ascorbic acid attenuates the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine in rats." Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacology. 1985 Feb;47(2):221–8. PMID 3992009

- ^ Wagner GC, Carelli RM, Jarvis MF. "Ascorbic acid reduces the dopamine depletion induced by methamphetamine and the 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium ion." Neuropharmacology. 1986 May;25(5):559–61. PMID 3488515

- ^ Oyler JM, Cone EJ, Joseph RE Jr, Moolchan ET, Huestis MA. "Duration of detectable methamphetamine and amphetamine excretion in urine after controlled oral administration of methamphetamine to humans." Clinical Chemistry. 2002 Oct;48(10):1703–14. PMID 12324487.

- ^ The Ice Age (See Below)

- ^ Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Carroll FI, Rice KC. "Neurochemical Neutralization of Methamphetamine With High-Affinity Nonselective Inhibitors of Biogenic Amine Transporters: A Pharmacological Strategy for Treating Stimulant Abuse." Synapse 2000 Mar 1;35(3):222–7. PMID 10657029

- ^ a b c d Winslow BT, Voorhees KI, Pehl KA (2007). "Methamphetamine abuse". American family physician. 76 (8): 1169–74. PMID 17990840.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grabowski, J.; et al. (2004). "Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence". Addictive Behaviors. 29 (7): 1439–1464. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.018. PMID 15345275. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Sleep medicine 'can help ice addicts quit'". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ AJ Giannini. Drugs of Abuse—Second Edition. Los Angeles, Practice Management Information Company, 1997.

- ^ Miller, MM. "Treatment of Narcolepsy with Methamphetamine". Sleep. 16 (4): 306–17. PMC 2267865. PMID 8341891. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Properties and effects of methamphetamine http://www.turningpoint.org.au/library/cg_14.pdf

- ^ "UM study: Meth may lessen stroke damage". AP. 2006-10-12. Archived from the original on 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ "Methamphetamine Use (Meth Mouth)". American Dental Association. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ Relationship between amphetamine ingestion and gingival enlargement

- ^ Shaner JW, Caries associated with methamphetamine abuse

- ^ Meth and Sexual Behavior - Drug-Rehabs.org

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/search.do?q=methamphetamine+labs&btnG.x=29&btnG.y=6&sort=date%3AD%3AL%3Ad1&oe=UTF-8&ie=UTF-8&ud=1&site=default_collection

- ^ Onset of Action and Drug Reinforcement http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/301/2/690.full.pdf

- ^ Meth Myths, Meth Realities[dead link]

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ http://www.illinoisattorneygeneral.gov/methnet/understandingmeth/basics.html

- ^ A Synthesis of Amphetamine. J. Chem. Educ. 51, 671 (1974)

- ^ Owen, Frank (2007). "Chapter 1: The Rise of Nazi Dope". No Speed Limit: The Highs and Lows of Meth. Macmillan. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9780312356163.

- ^ Associated Press (August 25, 2009). "New 'shake-and-bake' method for making crystal meth gets around drug laws but is no less dangerous". New York Daily News.

- ^ "Shake and Bake Meth - New 'Shake and Bake' Meth Method Explodes". Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ Law Enforcement Facts, 2007

- ^ DEA Congressional Testimony, "Drug Threats And Enforcement Challenges". U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. March 22, 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ "Methamphetamine - National Drug Threat Assessment 2006". National Drug Intelligence Center. January 2006. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- ^ Mexico says pseudoephedrine case signals breakdown in port security in U.S., China AP, The Telegram (The Canadian Press), July 26, 2007. Olga R. Rodriguez

- ^ The Price and Purity of Illicit Drugs: 1981 Through the Second Quarter of 2003

- ^ The Ice Epidemic http://www.wctu.com.au/pages/education_papers/Education%20Paper%202007-09.pdf

- ^ Candy Flavored Meth Targets New Users CBS News, May 2, 2007. Lloyd De Vries. Accessed 2009-12-29.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara. "snopes.com: Strawberry Meth". Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- ^ BA Clement, CM Goff, TDA Forbes, Phytochemistry Vol.49, No 5, pp1377–1380 (1998) "Toxic amines and alkaloids from Acacia rigidula"

- ^ Ask Dr. Shulgin Online: Acacias and Natural Amphetamine

- ^ Siegler, D.S. (2003). "Phytochemistry of Acacia—sensu lato". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 31 (8): 845–873. doi:10.1016/S0305-1978(03)00082-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/DrugFact/methamphetamine/methamphetamine_ff.html

- ^ Plüddemann, Andreas (2005-06). "Tik, memory loss and stroke". Science in Africa. South Africa: Science magazine for Africa CC. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ What is methamphetamine? - New Zealand Police

- ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

Further reading

- Yudko, Errol (2008-10-29). Methamphetamine Use: Clinical and Forensic Aspects. 408 (2 ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0849372735.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- [2]

- NLM Hazardous Substances Data Bank - Entry for d-methamphetamine

- Erowid Methamphetamine Vault

- EMCDDA drugs profiles: Methamphetamine (2007)

- EMCDDA paper on Methamphetamine supply in Europe (2009)

- A Key to Methamphetamine-Related Literature - A comprehensive thematic index of methamphetamine research published in academic and scientific journals with links from citations to the PubMed abstracts.

- Meth FAQ - More detailed synthesis and synthesis from other sources.

- DEA's Methamphetamine News Releases

- Poison Information Monograph (PIM 334: Methamphetamine)

- Chronic Amphetamine Use and Abuse - a thorough review on the effects of chronic use (American College of Neuropsychopharmacology)

- [3] - Self Help Guide for Family Members and Loved Ones of Meth Addicts

Documentaries

- The Ice Age - ABC Australia - 4 Corners — Australian methamphetamine use.

- Frontline - The Meth Epidemic - PBS United States — Frontline.

- The World's Most Dangerous Drug - National Geographic.

- The City Addicted to Crystal Meth - BBC (Louis Theroux)