Medical racism in the United States

Medical racism in the United States encompasses discriminatory and targeted medical practices, as well as misrepresentations in medical education, usually driven by biases based on characteristics of patients' race and ethnicity. In American history, it has impacted various racial and ethnic groups and affected their health outcomes,[1] especially vulnerable subgroups such as women, children and the poor. As an ongoing phenomenon since at least the 18th century, examples of medical racism include various unethical studies, forced procedures, and differential treatments administered by health care providers, researchers, and government entities. Whether medical racism is always caused by explicitly prejudiced beliefs about patients based on race or by unconscious bias is not widely agreed upon.[2][3]

History

[edit]

The history of medical racism has created a deep distrust of health professionals and their practices among many people in marginalized racial and ethnic groups. Studies within the last couple decades have elucidated ongoing disparate treatment from health professionals, revealing racial biases. These racial biases have impacted the way in which treatments such as painkillers are prescribed and the rate at which diagnostic tests are given.[2] Black patients in particular have a long history of contrasting medical treatment based on different perceptions of the pain thresholds of Black people.[5][6] The eugenics movement is an example of how racial bias affected the treatment of women of color, specifically African American women. However, medical racism has not been limited to Black people in the United States. While studies like the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male are infamous, the U.S. Public Health Service Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Inoculation Study of 1946-1948 harmed Guatemalan prisoners, sex workers, soldiers, and mental health patients by purposely infecting victims with STDs such as syphilis and gonorrhea.[2] Forcible sterilization of Indigenous women as young as 15 years old occurred from 1970 to 1976 by the Indian Health Service as revealed in researcher Jane Lawrence's paper "The Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American Women."[2] Many other examples exist in American history of the unethical actions of health care providers, researchers, and government entities pertaining to the health services of minority groups.[2]

Contributing factors

[edit]Cultural competence

[edit]Physicians who are not culturally competent can harm patients due to poor relationship dynamics, contributing to medical racism. Racism is defined as “a form of social formation embedded within a network of social, economic, and political entities in which groups of people are categorized...” As a result, there are groups of people that are racialized as inferior. Most times, individuals tend to categorize these groups with negative stereotypes with connotations that have a high level of acceptance and endorsement. While physicians may consciously condemn racism and negative stereotypes, evidence shows that doctors exhibit the same levels of implicit bias as the greater population. Racialized minority groups report experiencing both overt and covert racism in healthcare interactions. Implicit bias is also seen in mental health services, which are plagued by disparities viewed through lenses of racial and cultural diversity. Much of the discrimination that occurs is not intentional. Healthcare providers may not consciously have biases on racial stereotypes. These tend to occur automatically. Psychological studies have demonstrated that “...persons who do not see themselves as prejudiced will make health care allocation decisions…”. Based on this research, several authors argue that there is an intense need for cultural competence education in healthcare for explicit racism and implicit biases.[7] Cultural incompetence exists for a number of reasons such as lack of diversity in medical education and lack of diverse members of medical school student and faculty populations. This leads to marginalization of both minority healthcare providers and minority patients.[8][9][5][10]

Medical education

[edit]The lack of medical education about minority groups is evident in various studies and experiences. In a 2016 study, white medical students incorrectly believed that Black patients had a higher pain tolerance than white patients, perpetuating harmful stereotypes. These beliefs were rooted in unfounded notions, such as thicker skin or less sensitive nerve endings in Black individuals, echoing racist ideologies of the past. This bias extends beyond education, as racialized minority healthcare users report feeling unjustly reprimanded and scolded by healthcare staff, as noted by African American women in the USA. Furthermore, research reveals disparities in pain medication prescriptions, with white male physicians prescribing less to Black patients, fueled by perceptions of biological differences in pain reactions between races. These findings underscore the urgent need for reforms in medical education to address racial biases and promote sensitivity. Additionally, statistics show that African Americans are disproportionately subjected to less desirable healthcare services, like limb amputations, highlighting systemic inequalities that several authors state must be confronted and rectified. Studies done on the curriculums of medical schools in the US have found that within the assigned textbook readings, there exists a disparity between the representation of race and skin color in textbook case studies relative to the US population. This is true for both visual and textual lecture materials.[8][10]

A group of studies done on the representation of race and gender in course slides for the University of Washington School of Medicine, preclinical lecture slides at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and case studies used at the University of Minnesota Medical School simultaneously showed associations of race as a "risk factor" and a lack of racial diversity.[9][10]

The study done on the University of Minnesota Medical School employed the use of the concept of hidden curriculum to describe the ways in which lack of representation and informal teachings can greatly influence the minds of aspiring physicians. The interactions had between students and faculty or the transmission of unintentional messages can be just as, if not more, influential than formal lectures.[10] These can include the associations of diseases such as sickle cell anemia as a "black disease" and cystic fibrosis as a "white disease" which leads to poor health outcomes.[9] In this study, the 1996-1998 year one and year two curriculums of the school were analyzed. It revealed that only 4.5% of the case studies mentioned a racial or ethnic background of the patient and when the patient was black or had "potentially unfavorable characteristics" race or ethnicity was more likely to be identified. There was also a greater prevalence of health-related themes discussed when race or ethnicity was identified. Researchers determined that the inclusion of specific racial or ethnic identities in those cases was intended to indicate something about that disease or health condition. The authors state that practices such as these contribute to the racialization of diseases.[10]

A study of medical textbooks has also yielded information on minority representation in medical teachings. Based on the required texts of the top 20 ranked medical schools in North America, US editions of Atlas of Human Anatomy (2014), Bates' Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking (2013), Clinically Oriented Anatomy (2014), and Gray's Anatomy for Students (2015) were chosen for the study. Using the total 4146 images from the four textbooks that depicted visible faces, arms, heads, and skin, researchers discovered two of three books were close in diversity to the US population, one book displayed "diversity on basis of equal representation" and one matched neither definition of diversity.[9] On a topic level there were also issues of diversity. When discussing health issues such as skin cancers three of four books included no imagery at all and the one book that did had only imagery of white and light-skinned patients. According to researchers, symptoms might manifest differently depending on skin tone. Missed indicators may go unreported if there is a lack of education on how to recognize these discrepancies.[9]

Some medical students have also done their own research and added to the discourse on underrepresentation in medical school education. They've noted specific examples such as skin infections like erythema migrans being depicted on almost exclusively white skin.[8] As an indicative first symptom of lyme disease, a lack of knowledge on how to detect this rash on patients with darker skin colors means failed diagnoses of the disease. Studies have shown that there is in fact a delay in lyme disease diagnoses for black patients.[8] The lack of representation in medical school lectures risks creating adverse impacts on the health outcomes of minority populations in the US.[8]

Representation in medical field

[edit]According to US Census data, black and Hispanic people account for 13% and 18% of the overall population, respectively. However, they only make up 6% and 5% of medical school graduates, respectively.[3] Black physicians make up only about 3% of American doctors.[2] Black physicians in particular have historically faced numerous obstacles to obtaining membership in the larger medical community. During the 20th century in the United States, groups such as the American Medical Association neglected black physicians and their pursuit of success in the field of medicine. This has led to continued marginalization of black physicians in the US due to their small numbers among other factors and this contributes to the marginalization of black patients.[2][5] Minorities often perceive medical facilities as "white spaces" because of a lack of diversity at the institutional level.[9]

Racial depictions

[edit]

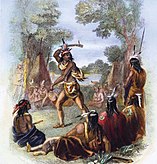

The dehumanization of certain racial groups such as black people can also contribute to disparities in healthcare due to varied perceptions, by physicians, of concepts such as pain tolerance and cooperation – one aspect of medical racism. In American history, social Darwinism has been utilized to justify American chattel slavery among other historical practices and the racist ideas about black people it created persisted into the 20th century.[5] The Three-Fifths Compromise worked also to reinforce the notion that black people were less than human.[11]

However, this has not just been relegated to the past. As recently as the 1990s, California state police came under fire for referring to cases involving young black men as "N.H.I" or no humans involved.[11] One police officer involved in the Rodney King beating in 1991 was cited as saying that a domestic quarrel between a black couple was "something right out of Gorillas in the Mist."[11] This comparison has historical prevalence in that it stems from early theorizations about the evolution of primates. Proponents of this social Darwinistic theory believe that white people are the most advanced humans, descended from primates, and that black people must fall somewhere in the middle of the two.[11]

Research published in 2008 studied undergraduate students from two universities in the United States. The researchers attempted to determine whether or not the association of black people with apes influenced the perceptions and behaviors of 242 white and non-white students, using a format in which images were presented to the subjects subliminally and their responses were recorded. The study found that even without explicit knowledge of the historical association, the students implicitly related one with the other.[11] This study was done in the context of criminal justice and aimed to reveal whether associations with animals impacted the likelihood of jurors to give the death sentence. Researchers were able to conclude that, "The present research foregrounds dehumanization as a factor in producing implicit racial bias, and we associate it with deadly outcomes."[11]

Socioeconomic status

[edit]Studies also show that social class is critical to the effects of racial disparities in health care, due to the correlation and relationship between health status and health insurance or the absence of.[12] There was an interview study of 60 African Americans whom of which had one or multiple illnesses and the results showed that those of whom fell under the low-income category expressed more dissatisfaction with their health care than their fellow middle-income respondents. Socioeconomic status is very entangled and highly associated with racism, which thus restricts many members of minority groups in various ways.[12] Low SES (socioeconomic status) is an important determinant to quality and access of health care because people with lower incomes are more likely to be uninsured, have poorer quality of health care, and or seek health care less often, resulting in unconscious biases throughout the medical field.[12]

A recent study at the Institute of Medicine reported that Whites are more likely than African Americans to receive a broader range of medical specific procedures while African Americans are more likely to receive undesirable procedures such as amputations and not as many options.[12] Of the study, respondents reflected their socioeconomic status, their professions, if they were homeowners, if they had medical insurance, versus those who lived in public housing, had no medical insurance, etc.[12] The study showed that SES directly correlated with health insurance status due to the fact that people that considered themselves as low-income, had a history of either being a Medicaid recipient or had no health insurance overall.[12]

Discrimination based on race is among those of who fall into a minority category, especially being of low-income due to the fact that medical practitioners tend to have more racial biases towards people of color.[12]

Personal experiences

[edit]Racial discrimination occurs on many different levels in a variety of different ways and contexts, and its severity is often affected by factors such as income, education, socioeconomic status, and location.[13]

In one study, participants from eight different focus groups, varying in race, discussed their experiences within health care, including the health care services they received. Some participants stated that they often felt that the quality of the health care they received directly stemmed from stereotyping, which in most cases did not reflect who they were.[13] They said they often felt that providers of health care treated them differently because of the assumption that they were less educated and poor, and that meant that they could be treated with less respect based on the color of their skin.[13]

Some participants were certain that they had been discriminated against in health care, but found it difficult to pinpoint exact situations or moments of discrimination.[13]

Focus group participants described encounters with providers who made stereotypical assumptions about them:

"My name is ... [ a common Hispanic surname ] and when they see that name, I think there is ... some kind of a prejudice of the name ... We're talking about on the phone, there's a lack of respect. There's a lack of acknowledging the person and making one feel welcome. All of the courtesies that go with the profession that they are paid to do are kind of put aside. They think they can get away with a lot because 'Here's another dumb Mexican.'" (Hispanic participant)[13]

"I've had both positive and negative experiences. I know the negative one was based on race. It was [with] a previous primary care physician when I discovered I had diabetes. He said, “I need to write this prescription for these pills, but you'll never take them and you'll come back and tell me you're still eating pig's feet and everything… Then why do I still need to write this prescription.” And I'm like, “I don't eat pig's feet.” (African American participant)[13]

"My son broke my glasses so I needed to go get a prescription so I could go buy a pair of glasses. I get there and the optometrist was talking to me as if I was like 10 years old. As we were talking, they were saying, “What do you do,” and as soon as they found out what I did [professionally], the whole attitude of this person changed towards me. I don't know if they come in there thinking, “Oh this poor Indian does not have a clue.” I definitely felt like I was being treated differently. "(Native American participant)[13]

"If you speak English well, then an American doctor, they will treat you better. If you speak Chinese and your English is not that good, they would also kind of look down on you. They would [be] kind of prejudiced." (Chinese participant)[13]

"I felt that because of my race that I wasn't serviced as well as a Caucasian person was. The attitude that you would get. Information wasn't given to me as it would have [been given to] a Caucasian. The attitude made me feel like I was less important. I could come to the desk and they would be real nonchalant and someone of Caucasian color would come behind me and they'd be like, “Hi, how was your day?” (African American participant)[13]

Black Americans

[edit]Black Americans have faced numerous obstacles to equal access to healthcare due to medical racism and the consequence of this has been poor health outcomes. Within this paradigm, American doctors and institutions have historically played a large role in perpetuating scientific racism, denying equal care to black patients, and perpetuating structural violence as well as committing acts of physical assault and violence against black people in the context of medical experimentation, withholding of treatment, medical procedures performed without consent, and surgical procedures performed without anesthesia[5][14]

Ideas about black people's relationship to primates and their biological and intellectual inferiority to white people, in the US, were just a few ways in which chattel slavery was justified.[6][15] Following this was the introduction of the belief that black people have much higher pain thresholds or the introduction of the belief that they do not feel pain at all.[5][6] Proponents of ideas such as this also proposed that black people had thicker skulls and less sensitive nervous systems, and they also proposed that black people contracted diseases which were linked to their darker skin color. Some proponents of these racist ideas even believed that black people could go through surgery without any pain medicine and they also believed that when black people were punished, during their enslavement, they felt no pain.[6] White American physicians also operated on the assumption that poor health was the status quo for black people which meant that they would naturally die off due to syphilis and tuberculosis, a situation which was detrimental to the quality of the healthcare which they then provided to black people. The high rate of syphilis among black people was used to reinforce this notion.[5][15] However, racial myths also have negative impacts on the health outcomes of black Americans, starting from infancy. Beliefs in the "supernormal health" of black babies and children fosters ignorance and leads to the avoidance of the health issues which black children face in their early lives. With a large role in the perpetuation of such widely believed ideas, oral traditions can be highly influential, even when they are not explicitly included within medical curriculum.[5]

When false ideas of pain tolerance based on race are present within people's minds, they lead to detrimental consequences even if those who believe in them have no explicitly prejudiced beliefs, as was discovered by researchers[6] in a study on racial bias in pain assessments. In this study, a correlation between racial bias in pain assessment and subsequent pain treatment suggestions was found. It was also found that in both a significant number of laypersons and those with medical training, incorrect beliefs about differences between black and white people on a biological level were held.[6] Beliefs such as these can lead to the differential treatment of patients on the basis of their race. Staton et al., showed that physicians had a higher probability of underestimating the pain intensity that black patients were feeling.[6] In the early 2000s, multiple studies demonstrated discrepancies in the pain treatment of black patients as compared to white patients. From children to adults, differences were as much as black patients only taking half of the amount of pain medications as white patients were taking.[2]

Freedom from slavery did not stop the impacts that slavery had on black people: the denial of access to healthcare recreated the experiences of slavery by exposing black people to many infectious diseases.[14] A notable difference between the services which were offered and rendered to black patients and the services which were offered and rendered to white patients has been observed in the American healthcare system even with the presentation of the same severity of symptoms and the same health insurance.[5]

Along with unequal access to medical care, medical racism has contributed to violence perpetrated against black Americans throughout history. Including the use of "resurrectionists" to retrieve newly buried bodies of deceased black people for medical study use, the bodies of black people were abused for forced medical experimentation for many years. As noted in writings on the American medical field's history of medical racism, "American medical education relied on the theft, dissection, and display of bodies, many of whom were black."[14] This is especially true for women, such as was the case for Henrietta Lacks. The nonconsensual experimentation on enslaved black women was used to help further the field of gynecology.[14] Following this, due to the history of eugenics in the United States, this same population once again fell victim to forced procedures, in this case sterilization. This went on in the US as late as the 1970s and 1980s as is documented in Killing the Black Body.[2][14] For black Americans, the involuntary sterilization of black women was so well known it began being referred to as the "Mississippi Appendectomy".[2]

The violence which was perpetrated by American physicians and institutions has a long, documented history. Besides the Tuskegee syphilis study, there are many other instances of experimentation on black populations without their knowledge or consent.[2][6] In 1951, the US Army intentionally exposed large numbers of black citizens to Aspergillus fumigatus to ascertain whether they were more susceptible to this fungus. In the same year, black workers at a Norfolk supply center in Virginia were exposed to crates contaminated with the same fungus.[2] Journalist Richard Sanders reported that from 1956 to 1958 the US Army intentionally released mosquitoes in poor black communities of Savannah, Georgia and Avon Park, Florida. Many people subsequently developed fevers for unknown reasons and some of them died, it is theorized that the mosquitoes were infected with a strain of yellow fever. Pulitzer-prize winning author of The Plutonium Files, Eileen Welsome wrote on how the US secretly injected thousands of Americans with plutonium while it was developing the atomic bomb. A number of these victims were black and they were completely unaware of the injections.[2]

Indigenous Americans

[edit]

Starting in the 18th century, the United States has committed many acts of medical injustice against Indigenous Americans. In the 18th century, smallpox was used as a biological weapon to wipe out indigenous populations. In particular, in 1763 Sir Jeffery Amherst ordered soldiers to take the blankets and handkerchiefs of smallpox patients and gift them to indigenous people of Delaware at a peacemaking parley.[2] There is also the prevalence of involuntary sterilization of young indigenous girls and women. From the data yielded by multiple studies, it was suggested that the Indian Health Service sterilized between 25 and 50% of indigenous women from 1970 to 1976.[2]

Contemporarily, the health outcomes of indigenous populations in the US are still vastly worse than the greater population. In the state of Montana, the life expectancy for indigenous women is 62, while for men it is 56. These numbers are significantly lower than the national averages by around 20 years.[16] This is due to a number of factors such as the fact that unequal funding plagues the Indian Health Service that is in charge of ensuring the access the federal government must provide and that around 25% of indigenous people in the US report facing discrimination in medical settings.[16][17] An executive director at South Dakota Urban Indian Health, Donna Keeler, explains that while her clinic receives federal funding for indigenous people living in urban areas, federal prison inmates would have more federal funding allocated to their healthcare.[16]

Hispanic Americans

[edit]

In the United States, 20% of Hispanic Americans report encountering discrimination in healthcare settings and 17% report avoiding seeking medical care due to expected discrimination.[18] Studies of Hispanic people living in the U.S. reveal that after experiencing an instance of discrimination in a healthcare setting they, afterward, delayed seeking medical treatment again.[7] The discrimination faced by Hispanic Americans can further contribute to the negative health outcomes that stem from the experience of racism and discrimination by minorities.[18] Cultural incompetency can hinder productive relationships between healthcare providers and patients because different cultural norms of communication can give the impression that a physician is not properly attending to the concerns of their patient as was found in studies on Latina experiences with the healthcare system. It was found in one study that in the role that communication plays in the dynamic between Latina patients and healthcare providers, the way women perceived their communication with their provider was greatly impactful to their perception of discrimination.[7]

The aforementioned U.S. Public Health Service Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Inoculation Study of 1946-1948 is just one historical example of the way in which Latin American populations have been victim to medical racism and medical injustices.[2]

Contemporary issues

[edit]From 2006 to 2013, California prisons performed illegal sterilizations on inmates[19] and more than half of the women were black or Latina.[6] Also in 2012, both black and Hispanic patients have been found to be under-treated for pain.[5]

In 2020, a nurse whistleblower alleged the practice of forced hysterectomies at a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility.[20]

Mitigation

[edit]In addressing the issue of medical racism in the United States, there are different ways to mitigate unconscious bias that leads to the perpetuation of health disparities. Practices like better diversity training, introspection of biases, "cultural humility and curiosity", and a full commitment to changing the culture of healthcare and the impact of stereotypes can work to lessen the effects that unconscious bias can have on patients.[3] Academia should assist medical students in recognizing and addressing race-based inequities and microaggressions. Curriculums that address racial bias could improve patient interactions with incoming healthcare professionals. A 2020 study of resident-led programs dedicated to racism training effectively promoted awareness of racism in the workplace. By generating awareness of institutional racism early on, better practices may help to mitigate further effects of medical racism.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ Care, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health; Smedley, Brian D.; Stith, Adrienne Y.; Nelson, Alan R. (2003), "Racial disparities in Health Care: Highlights From Focus Group Findings", Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 2023-10-30

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Dossey, Larry (2015). "Medical Racism". Explore. 11 (3): 165–174. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2015.02.009. ISSN 1550-8307. PMID 25899689.

- ^ a b c Marcelin, Jasmine R.; Siraj, Dawd S.; Victor, Robert; Kotadia, Shaila; Maldonado, Yvonne A. (20 August 2019). "The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 220 (Suppl 2): S62–S73. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz214. ISSN 1537-6613. PMID 31430386.

- ^ Duff-Brown, Beth (January 6, 2017). "The shameful legacy of Tuskegee syphilis study still impacts African-American men today". Stanford Health Policy. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hoberman, John M. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism / John Hoberman. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hoffman, Kelly M.; Trawalter, Sophie; Axt, Jordan R.; Oliver, M. Norman (19 April 2016). "Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (16): 4296–4301. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.4296H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516047113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4843483. PMID 27044069.

- ^ a b c Sheppard, Vanessa B.; Williams, Karen Patricia; Wang, Judy; Shavers, Vickie; Mandelblatt, Jeanne S. (1 June 2014). "An Examination of Factors Associated with Healthcare Discrimination in Latina Immigrants: The Role of Healthcare Relationships and Language". Journal of the National Medical Association. 106 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30066-3. ISSN 0027-9684. PMC 4838486. PMID 26744111.

- ^ a b c d e Khan, Shujhat; Mian, Areeb (1 September 2020). "Racism and medical education". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20 (9): 1009. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30639-3. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 32860760. S2CID 221373310.

- ^ a b c d e f Louie, Patricia; Wilkes, Rima (1 April 2018). "Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery". Social Science & Medicine. 202: 38–42. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.023. ISSN 0277-9536. PMID 29501717.

- ^ a b c d e Turbes, Sandra; Krebs, Erin; Axtell, Sara (March 2002). "The Hidden Curriculum in Multicultural Medical Education: The Role of Case Examples". Academic Medicine. 77 (3): 209–216. doi:10.1097/00001888-200203000-00007. ISSN 1040-2446. PMID 11891157. S2CID 44816059.

- ^ a b c d e f Goff, Phillip Atiba; Eberhardt, Jennifer L; Williams, Melissa J; Jackson, Matthew Christian (1 February 2008). "Not yet human: implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (2): 292–306. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 18211178.

- ^ a b c d e f g Becker, Gay; Newsom, Edwina (May 2003). "Socioeconomic Status and Dissatisfaction With Health Care Among Chronically Ill African Americans". American Journal of Public Health. 93 (5): 742–748. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.5.742. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1447830. PMID 12721135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Care, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health; Smedley, Brian D.; Stith, Adrienne Y.; Nelson, Alan R. (2003), "Racial disparities in Health Care: Highlights From Focus Group Findings", Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 2023-11-15

- ^ a b c d e Nuriddin, Ayah; Mooney, Graham; White, Alexandre I. R. (3 October 2020). "Reckoning with histories of medical racism and violence in the USA". The Lancet. 396 (10256): 949–951. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32032-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7529391. PMID 33010829.

- ^ a b Byrd, W Michael, Linda A Clayton. “Race, Medicine, and Health Care in the United States: A Historical Survey.” Journal of the National Medical Association: Race, Medicine and Health Care 93, no. 3 (March 2001): 11S-34S.

- ^ a b c Whitney, Eric (December 12, 2017). "Native Americans Feel Invisible in U.S. Health Care System". NPR.org. National Public Radio.

- ^ Friedman, Misha (13 April 2016). "For Native Americans, Health Care Is A Long, Hard Road Away". NPR.

- ^ a b Findling, Mary G.; Bleich, Sara N.; Casey, Logan S.; Blendon, Robert J.; Benson, John M.; Sayde, Justin M.; Miller, Carolyn (2019). "Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Latinos". Health Services Research. 54 (S2): 1409–1418. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13216. ISSN 1475-6773. PMC 6864375. PMID 31667831.

- ^ "California compensates victims of forced sterilizations, many of them Latinas". NBC News. 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2024-11-14.

- ^ Treisman, Rachel. "Whistleblower Alleges 'Medical Neglect,' Questionable Hysterectomies Of ICE Detainees". NPR. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Chary, Anita N.; Molina, Melanie F.; Dadabhoy, Farah Z.; Manchanda, Emily C. (2021). "Addressing Racism in Medicine Through a Resident-Led Health Equity Retreat". Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 22 (1): 41–44. doi:10.5811/westjem.2020.10.48697. ISSN 1936-900X. PMC 7806337. PMID 33439802.

- ^ Race as Biology Is Fiction, Racism, as a Social Problem Is Real | Anthropological and Historical Perspective on the Social Construction of Race.(2005, January). Audrey Smedley, Virginia Commonwealth University; Brian D. Smedley, Institute of Medicine

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, September 18). Racism and health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/racism-disparities/index.html

- ^ Racial discrimination in healthcare: How structural racism affects healthcare. St. Catherine University. (2021, June 15).

- ^ Racism in Healthcare: A Scoping Review.(2020, December 1). Sarah Hamed, Hannah Bradby, Beth Maina Ahlberg, Suruchi Thapar-Bjorkert.

- ^ Williams, D. R., & Rucker, T. D. (2000). Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health care financing review.