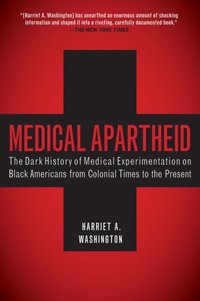

Medical Apartheid

Paperback edition cover | |

| Author | Harriet A. Washington |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Ron Butler |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Unethical human experimentation in the United States |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | 9 January 2007 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print, e-book |

| Pages | 512 pp. |

| ISBN | 978-0385509930 |

Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present is a 2007 book by Harriet A. Washington. It is a history of medical experimentation on African Americans. From the era of slavery to the present day, this book presents the first detailed account of black Americans' abuse as unwitting subjects of medical experimentation.[1][2]

Medical Apartheid won the 2007 National Book Critics Circle Award for Non-fiction.[3] Washington's work helped lead to the American Medical Association's apology to the nation’s black physicians in 2008 and the removal of the James Marion Sims statue from Central Park in 2018.[4][5][6]

Synopsis

[edit]Medical Apartheid traces the complex history of medical experimentation on Black Americans in the United States since the middle of the eighteenth century. Harriet Washington argues that "diverse forms of racial discrimination have shaped both the relationship between white physicians and black patients and the attitude of the latter towards modern medicine in general".[7]

The book is divided into three parts: the first is about the role of African Americans in early American medicine and the cultural memory of medical experimentation; the second covers the twentieth century with a focus on vulnerable research subjects, while the last examines recent cases of medical abuse and research. Some topics discussed are well-known, such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, but other episodes are less well known to the general public.[7] In the epilogue, Washington mentions cases of medical experimentation in Africa and their links to African-American cases. She also provides recommendations for moving forward, including repairing the system of institutional review boards, banning exceptions to informed consent, requiring researchers to receive education in the ethics of biomedical research, and requiring researchers to follow the same research standards at home and abroad.[8]

Topics covered

[edit]Part 1: A Troubling Tradition

[edit]In Part 1 of the book, Washington discusses scientific racism and its intersection with unethical medical testing during slavery and afterwards. She describes how enslaved and free African Americans were exploited and mistreated by doctors and used in medical experiments.

James Marion Sims

[edit]One of the most infamous examples Washington describes is James Marion Sims, a doctor from South Carolina often considered the "father of gynecology".[4][9] Washington details the misdiagnosis of the medical conditions his patients suffered from during his medical training and the mistreatment of black enslaved women that led to his medical breakthrough.

Washington describes how Sims used black infants for tetany experiments. Sims determined through his research that the cause of tetany in the babies was a result of the movement of skull bones during birth. In order to test his theory, he took a black baby and, using a shoemaker's tools, opened the baby's brain based on his belief that black babies' skulls grew faster than the skulls of white babies, preventing their brains from growing or developing. Most of the babies died and he blamed their deaths on their supposed lack of intelligence.[10][11]

The most infamous example of Sims' medical malpractice was his research on vesicovaginal fistulas, a complication of childbirth. Sims acquired four enslaved women and used their bodies in order to find a cure. Sims mistreated the women, including by making them completely undress (despite modesty standards of the time) while he and other doctors examined them. He also put the women through painful surgeries without giving them anesthesia and Washington writes, "he claimed that his procedures were 'not painful enough to justify the trouble and risk of attending the administration,' but this claim rings hollow when one learns that Sims always administered anesthesia when he performed the perfected surgery to repair the vaginas of white women in Montgomery a few years later. Sims also cited the popular belief that blacks did not feel pain in the same way as whites."[12] Despite this, he received much fame and attention for his breakthrough. Because of his experiments on black women, Sims was eventually able to help white women who experienced vesicovaginal fistulas, but black women still did not have access to these treatments and many of them died from the same disease that the enslaved women helped to cure.[13][9]

Exhibiting of African Americans

[edit]Washington discusses cases of Africans and African Americans exhibited in human zoos and freak shows, including famous and lesser known cases. Washington argues that "[a]round 1840, entrepreneurs realized that a market hungered for black exotica, and they took a leaf from the physicians' book by displaying blacks as medical curiosities", and that these displays were "a dramatic argument for the alien inferiority of black bodies".[14]

Cases Washington describes include:

- Ota Benga, a Mbuti (Congo pygmy) man kidnapped by slave traders and exhibited in the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition and in the Bronx Zoo. Outrage from African American newspapers and black churches helped pressure the mayor of New York City into releasing him in 1906. After his release, Benga learned English and obtained a job, but developed depression because he could not return to Africa and died by suicide in 1916.[15]

- Sarah Baartman was a Khoikhoi woman exhibited in 19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus. She was displayed in Cape Town by the man whose household she worked for, and eventually toured Europe and became a popular attraction. It is unknown to what extent she consented to be exhibited and how much of the profits she received. She died in December 1815 around age 26 of an undetermined disease. Scientist Georges Cuvier preserved her skeleton, brain, and genitalia, and they were displayed at several French museums.[16] After a formal request from President Nelson Mandela, her remains were repatriated to her homeland in 2002.[17]

- Joice Heth was exhibited by P.T. Barnum with the false claim that she was the 161-year-old nursing mammy of George Washington. She attracted considerable public attention and speculation. After her death in February 1836, Barnum arranged for a public autopsy in front of fifteen hundred spectators, charging admission of US$0.50. When the surgeon declared the age claim a fraud, Barnum insisted that the autopsy victim was another person, and that Heth was alive, on a tour to Europe. Barnum later admitted the hoax. Heth was likely 79-80 years old when she died. Little is known of her early life other than she was once enslaved.[18]

Dissection and Grave Robbing

[edit]As the number of medical schools in the United States increased and as science and medicine evolved, demand for cadavers for doctors to dissect increased. Laws in some states allowed medical schools to use the remains of those at the bottom of society's hierarchy—the unclaimed bodies of poor persons and residents of almshouses, and those buried in potter's fields for anatomical study. Doctors also turned to hiring men to carry out grave robberies. According to Washington, the majority of bodies used for dissection were of African Americans.[19]

Washington describes the 1989 discovery beneath the Medical College of Georgia for thousands of bones once used for dissection. Approximately 75% of the bones belonged to African Americans, despite the nearby population only being 42% African American.[20]

Also discussed is the Negroes Burial Ground (now known as the African Burial Ground National Monument), New York's earliest known African-American cemetery; studies show an estimated 15,000 African American people were buried there.[21] The revelation that physicians and medical students were illegally digging up bodies for dissection from the burial ground precipitated the 1788 Doctors' Riot.

Tuskegee Syphilis Study

[edit]One of the most infamous examples of the medical mistreatment of African Americans Washington discusses is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which was a study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on a group of nearly 400 African American men with syphilis. The purpose of the study was to observe the effects of the disease when untreated, though by the end of the study medical advancements meant it was entirely treatable.[22] The men were not informed of the nature of the experiment and by the end of the study, 28 patients had died directly from syphilis, 100 died from complications related to syphilis, 40 of the patients' wives were infected with syphilis, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.[23]

A public outcry ensued after newspapers broke the story in 1972, and Senator Edward Kennedy called Congressional hearings and the CDC and PHS appointed an ad hoc advisory panel to review the study. As a result of the panel's investigation, the study was ended and new laws regulating human experimentation were passed. For Medical Apartheid Washington conducted new interviews with panel members, and members shared for the first time publicly discord behind the scenes of the investigation. Several members felt they were not given enough resources and the scope of their investigation was too limited. Panel members also shared with Washington that chairperson Dr. Broadus Butler steered the panel toward a softer version of the final report that removed references to intentional racism on the part of the study doctors, and that he convinced the panel to destroy tapes of some of their interviews.[24]

The study is often cited as a reason for African Americans' distrust of the medical system.[25][26] However, Washington writes:

"[b]y focusing upon the single event of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study rather than examining a centuries-old pattern of experimental abuse, recent investigations tend to distort the problem, casting African Americans' wariness as an overreaction to a single event rather than an understandable, reasonable reaction to the persistent experimental abuse that has characterized American medicine's interaction with African Americans".[27]

Part 2: The Usual Subjects

[edit]In Part 2 of the book, Washington discusses experiments in the 20th century done on individuals who did not give informed consent and were often in vulnerable positions. Cases she discusses include experiments done on incarcerated individuals, with a focus on one of the most famous examples, Holmesburg Prison; experiments on juvenile boys with the goal of studying the XXY syndrome and identifying so-called violent genes; and human radiation experiments done on people who were seeking other medical care. In these cases, not only black people were part of the experiments, but Washington argues that they were disproportionately targeted and that they were more often selected for more dangerous experiments.[28]

Reproductive Rights

[edit]Washington discusses reproductive rights, including the development of contraception and forced sterilization, and their connection to unethical medical experiments and scientific racism.

Washington mentions Margaret Sanger, a birth control activist and the founder of Planned Parenthood. She has been accused of engaging in negative eugenics through the Negro Project, which was the opening of birth control clinics in black neighborhoods with the intention of reducing black social ills.[29][30]

Washington describes the development of contraceptive technologies including the birth control pill, Norplant, and Depo-Provera, which were initially tested on women in Mexico, Africa, Brazil, Puerto Rico, and India, and then were first administered in neighborhoods in the U.S. that were mainly African American and Hispanic. Washington writes,

"[m]any serious effects emerge for the first time during this postapproval stage, when very large numbers of women begin taking the drug. Thus, the immediately postapproval use of contraceptive methods in large numbers of closely monitored poor women of color constituted a final testing arm, so that they were unwittling participating in a research study...In patterns too consistent to be accidental, reproductive drug testing makes poor women of color, at home and abroad, bear the brunt of any health risks that emerge."[31]

Additionally, Washington discusses the history of forced sterilization. The practice of sterilizing people believed to have genetic defects became increasingly common in the 1900s, and by 1941 an estimated 70,000 - 100,000 Americans had been forcibly sterilized. African Americans were disproportionately targeted. Famous cases Washington describes include the Relf sisters, who were 12 and 14 when they were sterilized without their consent in 1973, and Fannie Lou Hammer, whose receipt of a hysterectomy while unconscious was what spurred her to become a civil rights activist. So many women received the same treatment as Hammer it was called a "Mississippi Appendectomy".[32]

Part 3: Race, Technology, and Medicine

[edit]In Part 3 of the book, Washington turns to modern issues such as genetic testing and the harvesting of genetic material. She mentions cases such as Henrietta Lacks, whose cells, taken without her knowledge during treatment for cervical cancer, would become the HeLa cell line and the source of invaluable medical data.[33] She also details discrimination in how punitive measures for containing infectious diseases such as containment therapy and mandatory contract tracing without privacy were applied.[34]

Sickle Cell Disease

[edit]Washington discusses sickle cell disease, which is an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blood cells. This leads to a rigid, sickle-like shape that can led to a number of health problems. It is most common in people from the Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and West African regions due to its protection against specific strains of malaria. However, misconceptions in the U.S. that only people of African descent carried the gene led to the widespread belief that it was a racial condition and to the labeling of it as "a black disease". In the 1960s, the federal government supported initiatives that encouraged workplaces to institute genetic screenings, with the goal of protecting employees who screened positive from environments that could trigger illness. However, in practice it led to discrimination, such as airlines grounding pilots and the U.S. Air Force Academy barring cadets. Sickle cell disease is recessive, meaning individuals must inherit two genes to develop the disease. The genetic screenings were not able to distinguish between carriers and people with the disease, which meant people who were healthy but carriers were dismissed from jobs.[35]

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

[edit]Washington also discusses drug testing and treatment for HIV/AIDS, a retrovirus that attacks the immune system that became a pandemic. She describes the drug trials in New York City in the 1980s through 2005, which were done on children primarily from the foster care system.[36] She interviewed family members, who said that informed consent was not always given and that they felt pressured by doctors and city welfare officials to continue the trials. Additionally, Washington describes how researchers did not always follow protocols for approving new research and drugs. While Washington does not argue the children were chosen because of their race, she writes, "research protocols with African American and Hispanic children, who constitute virtually all the American children living with HIV, have exposed an alarming willgness to jeopardize their health and rights".[37]

Government Biological Warfare Research

[edit]Washington details tests done as part of MKNAOMI on unknowing American citizens by the U.S. government in the 1950s through 1970s to develop weapons for biological warfare. She discusses tests where the government released swarms of mosquitos into predominately black neighborhoods with the intention of seeing if they could be used to spread yellow fever and other infectious diseases.[38][39] Washington contrasts the "egregious assaults on the health of black Floridians, Georgians, and Virgin Islanders" with a report from 1969 that details how plans to test zinc cadmium sprays to determine the extent of the fallout were canceled due to concern about the possible health effects on bald eagles.[38]

Awards & Reception

[edit]Medical Apartheid won the 2007 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction.[3] It also won a PEN/Oakland Award,[40] BCALA Nonfiction Award,[41] and Gustavus Myers Outstanding Book Award.[42] It was selected as one of Publishers’ Weekly Best Books of 2006.[43]

Medical Apartheid received generally favorable reviews. In their starred review, Publisher's Weekly wrote "Washington is a great storyteller, and in addition to giving us an abundance of information on "scientific racism," the book, even at its most distressing, is compulsively readable".[44] Kirkus Review called the book "sweeping and powerful".[45] For The New York Times, Denise Grady was more mixed, writing "[s]ome of Washington's arguments are less convincing than others", but adding, "this is an important book. The disgraceful history it details is a reminder that people in power have always been capable of exploiting those they regard as "other," and of finding ways to rationalize even the most atrocious abuse".[46]

See also

[edit]- Killing the Black Body

- Human Guinea Pigs

- The Plutonium Files

- Acres of Skin

- List of medical ethics cases

- Compulsory sterilization in the United States

- Medical racism in the United States

- Unethical human experimentation in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present Archived 2024-09-29 at the Wayback Machine Google Books.

- ^ Alondra Nelson. Unequal Treatment: How African Americans have often been the unwitting victims of medical experiments Archived 2021-07-18 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post, January 7, 2007.

- ^ a b "The National Book Critics Circle Awards". National Book Critics Circle. Archived from the original on September 29, 2024. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Sayej, Nadja (April 21, 2018). "J Marion Sims: controversial statue taken down but debate still rages". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ Sidhu, Jonathan (July 16, 2008). "Exploring the AMA's History of Discrimination". ProPublica. Archived from the original on September 25, 2024. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ Boulden, Ben (September 9, 2024). "UAMS to Host Winthrop Rockefeller Distinguished Lecture, 'Medical Apartheid … and Beyond' on Sept. 25". UAMS News. Archived from the original on September 29, 2024. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present Social History of Medicine (2007) 20 (3): 620-621.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 401–405. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ a b Domonoske, Camila (April 17, 2018). "'Father Of Gynecology,' Who Experimented On Slaves, No Longer On Pedestal In NYC". NPR. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Holland, Brynn (4 December 2018). "The 'Father of Modern Gynecology' Performed Shocking Experiments on Slaves". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 2021-08-16. Retrieved 2018-12-13.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 7. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 63–67. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 89. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 75–79. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 82–85. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ "'Hottentot Venus' goes home". BBC News. April 29, 2002. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 85–89. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 117. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 120. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ "African Burial Ground". National Park Service. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "The U.S. Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 166. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 169–175. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ "Final Report of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee — May 1996". May 1996. Archived from the original on 2017-07-05. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Gamble, V.N. (November 1997). "Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care". Am J Public Health. 88 (11): 1773–1778. doi:10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. PMC 1381160. PMID 9366634.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 178. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 236, 240, 247, 255, 266, 277, 281, 283. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 195–198. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ "Margaret Sanger: Ambitious Feminist and Racist Eugenicist". The University of Chicago. September 1, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 202. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 202–206. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Grady, Denise (February 1, 2010). "A Lasting Gift to Medicine That Wasn't Really a Gift". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid [325, 337-339]. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 307–313. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ "Vera Institute Releases Final Report on NYC Foster Children in Clinical Trials for HIV/AIDS". Vera Institute. Retrieved October 3, 2024.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 332–337. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ a b Washington, Harriet A. (January 8, 2008). Medical Apartheid. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 359–365. ISBN 9780767915472.

- ^ Landers, Mary (February 6, 2021). "As COVID vaccine arrives, many Blacks in Savannah haunted by memory of infamous mosquito experiment". Savannah Morning News. Retrieved October 3, 2024.

- ^ "Awards & Award Winners". PEN Oakland. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "BCALA announces 2007 Literary Awards". American Library Association. January 29, 2007. Archived from the original on September 29, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Gustavus Myers Outstanding Book Award". Library Thing. Archived from the original on September 29, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "PW's Best Books of the Year". Publisher's Weekly. November 3, 2010. Archived from the original on July 13, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present". Publisher's Weekly. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Medical Apartheid". Kirkus Reviews. October 1, 2006. Archived from the original on September 29, 2024. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ Grady, Denise (January 24, 2007). "Book Review: Medical Apartheid - Culture - International Herald Tribune". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- 2007 non-fiction books

- American history books

- History books about medicine

- 21st-century history books

- Books about African-American history

- Human subject research in the United States

- Medical books

- National Book Critics Circle Award–winning works

- Human rights abuses in the United States

- Race and health in the United States

- Doubleday (publisher) books

- J. Marion Sims