Looting of Battleford

| Looting of Battleford | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North-West Rebellion | |||||

Fort Battleford National Historic Site | |||||

| |||||

The Looting of Battleford began at the end of March, 1885, during the North-West Rebellion, in the town of Battleford, Saskatchewan, then a part of the Northwest Territories.

Within days of the Métis victory at the Battle of Duck Lake on March 26, 1885. Cree bands sympathetic to the Métis cause and with grievances of their own began raiding stores and farms in the western part of the District of Saskatchewan for arms, ammunition and food supplies while civilians fled to the larger settlements and forts of the North-West Territories.

Prominent leaders of this uprising were Chief Poundmaker and Chief Big Bear. Poundmaker and his band had a reserve near present-day Cut Knife about 50 km (31 miles) west of Fort Battleford. Big Bear and his band had settled near Frog Lake about 55 km (34 miles) northwest of Fort Pitt but had not yet selected a reserve site.[1] Both bands were signatories of Treaty 6 and were unhappy in the way it was implemented by the Canadian government. The loss of the buffalo and the inadequate rations provided by the Indian agents kept the bands in a continual state of near-starvation.[2]

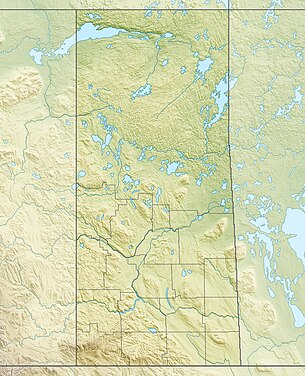

Geography

[edit]The District of Saskatchewan in 1885 was divided into three sub-districts and had a population of 10,595. To the east the Carrot River sub-district with 1,770 people remained quiet. The Prince Albert sub-district located in the centre of the district had a population of 5,373 which included the Southbranch settlements with about 1,300. The Southbranch settlements was the centre of Louis Riel's Provisional Government during the Rebellion. To the west where the Cree uprising led by Poundmaker and Big Bear occurred was the Battleford sub-district with 3,603 people.[3][4]

The largest settlement and the capital of the district was Prince Albert with about 800 people[5] followed by Battleford with about 500 people "divided about equally between French, Métis and English".[6]

Battleford is located on the Battle River near the North Saskatchewan River. On the south side of the Battle River was the Old Town and on the north side nearest the North Saskatchewan River was the New Town and Fort Battleford.[7]

The city of North Battleford was founded later in 1905 when the construction of the Canadian Northern Railway main line to Edmonton placed the line on the north side of the North Saskatchewan River.[8]

Siege of Battleford

[edit]

On March 28, as news that several Indian bands including Poundmaker's were on their way to Battleford settlers began moving into the nearby North-West Mounted Police post, Fort Battleford which was under the command of Colonel Morris and 25 police. Over the next several days 500 civilians would take refuge within the palisades. Many crossed over an unstable ice bridge on the Battle River leaving most of their possessions behind in the Old Town. During the night of March 29 nearby homesteads were raided their horses and cattle rounded up by the bands.[9]

Also on the trail to join Poundmaker in Battleford were the Assiniboine from the Eagle Hills approximately 30 km south of Battleford. On March 29, they killed their farm instructor John Payne and raided homesteads, on the way killing a farmer by the name of Fremont.[9]

On March 30, Poundmaker asked for a meeting with the Indian agent J. M. Rae. After Rae refused to meet with him, the combined Battleford bands took food and supplies from the abandoned stores and houses. The next day, the bands camped a few miles away bringing with them their looted provisions including cattle and horses then eventually returned to Poundmaker's reserve.[9]

The New Town was protected by its proximity to the Fort and its cannon, but the Old Town was not. Every day until the arrival of Colonel Otter's column on April 24, the occupants of the Fort watched as the Old Town, about a mile away, was plundered. Stolen vehicles and horses carried away the supplies of the Hudson's Bay Company and the other merchants. All the public buildings were sacked, including the Battleford Industrial School (located in the Old Government House).[10] Most homes were burned, including the imposing home of Judge Charles Rouleau. Just half a dozen were left standing.[11]

Aftermath

[edit]

On May 2, Colonel Otter's column attacked Poundmaker's camp at Cut Knife Creek but was forced to retreat to Battleford. Poundmaker prevented his warriors from attacking the retreating troops.[9]

On May 14, at Eagle Hills a Battleford band captured a wagon train carrying supplies for Colonel Otter's column.

After the defeat of the Métis force at the Battle of Batoche and the surrender of Louis Riel to Middleton on May 15, Poundmaker surrendered to General Middleton at Fort Battleford on May 26. It is estimated that three loyalists and around seven natives were killed in action as a result of the Siege of Battleford.[12]

Historiographical interpretation

[edit]The nature of the Cree advance on Battleford, like the entire 1885 Rebellion, is a source of historiographical controversy. Historian Douglas Hill characterized the Cree group as a "war party ... ready to take revenge for a winter of incalculable suffering" who "swooped on Battleford, killing six whites". George F. G. Stanley's writing on the subject indicated that the Cree were not murderous but more haphazard and bumbling: they "[did] not appear to have in mind an attack upon the town" but were content with "prowling around the neighbourhood". While John L. Tobias says that the Crees tried to demonstrate their "peaceful intent" by including women and children in their group, simply took food to sustain themselves after finding the town abandoned, and then withdrew to avoid conflict with the police.

References

[edit]- ^ William Bleasdell Cameron (1888), The war trail of Big Bear (pp. 43–46), Toronto: Ryerson Press (published 1926), retrieved 2014-04-10

- ^ "Treaty 6". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina. 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ^ Henry Thomas McPhillips (1888), McPhillips' alphabetical and business directory of the district of Saskatchewan, N.W.T.: Together with brief historical sketches of Prince Albert, Battleford and the other settlements in the district, 1888 (page 23), Prince Albert, NWT: Henry Thomas McPhillips, retrieved 2014-04-10

- ^ "FRENCH AND MÉTIS SETTLEMENTS". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina. 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- ^ Henry Thomas McPhillips (1888), McPhillips' alphabetical and business directory of the district of Saskatchewan, N.W.T.: Together with brief historical sketches of Prince Albert, Battleford and the other settlements in the district, 1888 (p. 65), Prince Albert, NWT: Henry Thomas McPhillips, retrieved 2014-04-10

- ^ Henry Thomas McPhillips (1888), McPhillips' alphabetical and business directory of the district of Saskatchewan, N.W.T.: Together with brief historical sketches of Prince Albert, Battleford and the other settlements in the district, 1888 (p. 53), Prince Albert, NWT: Henry Thomas McPhillips, retrieved 2014-04-10

- ^ Mulvaney, Charles Pelham (1885), The history of the North-West Rebellion of 1885 (Map of Battleford 1885) p.106, Toronto: A.H. Hovey & Co, retrieved 2014-04-10

- ^ "North Battleford". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina. 2006. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ^ a b c d Laurie, Patrick Gammie (April 23, 1885). "Battleford Beleaguered". Saskatchewan Herald. Battleford, Saskatchewan. pp. VOL. V11., No 15.

- ^ "Government House, Battleford". Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ^ Mulvaney, Charles Pelham (1885), The history of the North-West Rebellion of 1885 (Otter's March to Battleford) p.109, Toronto: A.H. Hovey & Co, retrieved 2014-04-10

- ^ a b "Numbered key, drawn in pen and ink, to accompany the painting "The Surrender of Poundmaker to Major General Middleton at Battleford, on May 26th, 1885"". Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- Hill, Douglas, The Opening of the Canadian West. Don Mills, ON: Academic Press 1967.

- Stanley, George F. G., Louis Riel: Patriot or Rebel. CHA Booklet #2, 1964.

- Tobias, John L., "Canada's Subjugation of the Plains Cree", Canadian Historical Review, LXIV (December 1983): 519–548.