Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Patel | |

|---|---|

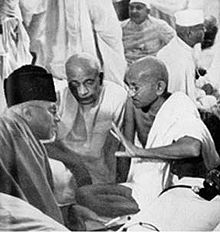

Patel in 1949 | |

| 1st Deputy Prime Minister of India | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| President | Rajendra Prasad |

| Governors General | |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Morarji Desai |

| 1st Minister of Home Affairs | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| President | Rajendra Prasad |

| Governors General | Louis Mountbatten C. Rajagopalachari |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | C. Rajagopalachari |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel 31 October 1875 Nadiad, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Died | 15 December 1950 (aged 75) Bombay, Bombay State, Dominion of India |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse |

Jhaverben Patel

(m. 1893; died 1909) |

| Children | |

| Relatives | Vithalbhai Patel (brother) |

| Alma mater | Middle Temple |

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (Gujarati: [ʋəlːəbːʰɑi dʒʰəʋeɾbʰɑi pəʈel]; ISO: Vallabhbhāī Jhāverbhāī Paṭel; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel,[a] was an Indian independence activist and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of India from 1947 to 1950. He was a senior leader of the Indian National Congress, who played a significant role in the Indian independence movement and India's political integration.[1] In India and elsewhere, he was often called Sardar, meaning "Chief" in Hindi, Urdu, Bengali and Persian. He acted as the Home Minister during the political integration of India and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947.[2]

Patel was born in Nadiad, Kheda district and raised in the countryside of the state of Gujarat.[3] He was a successful lawyer. One of Mahatma Gandhi's earliest political lieutenants, he organised peasants from Kheda, Borsad and Bardoli in Gujarat in non-violent civil disobedience against the British Raj, becoming one of the most influential leaders in Gujarat. He was appointed as the 49th President of Indian National Congress. Under the chairmanship of Patel "Fundamental Rights and Economic Policy" resolution was passed by the Congress. Patel's position at the highest level in the Congress was largely connected with his role from 1934 onwards (when the Congress abandoned its boycott of elections) in the party organisation. Based at an apartment in Bombay, he became the Congress's main fundraiser and chairman of its Central Parliamentary Board, playing the leading role in selecting and financing candidates for the 1934 elections to the Central Legislative Assembly in New Delhi and for the provincial elections of 1936.[4] While promoting the Quit India Movement. Patel made a climactic speech to more than 100,000 people gathered at Gowalia Tank in Bombay on 7 August 1942. Historians believe that Patel's speech was instrumental in electrifying nationalists, who up to then had been sceptical of the proposed rebellion. Patel's organising work in this period is credited by historians with ensuring the success of the rebellion across India.[5]

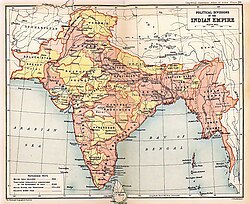

As the first Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister of India, Patel organised relief efforts for partition refugees fleeing to Punjab and Delhi from Pakistan and worked to restore peace. Besides those provinces that had been under direct British rule, approximately 565 self-governing princely states had been released from British suzerainty by the Indian Independence Act 1947 (10 & 11 Geo. 6. c. 30). Patel, together with Jawaharlal Nehru and Louis Mountbatten persuaded almost every princely state to accede to India.[6]

Patel's commitment to national integration in the newly independent country earned him the sobriquet "Iron Man of India".[7] He is also remembered as the "patron saint of India's civil servants" for playing a pioneering role in establishing the modern All India Services system. The Statue of Unity, the world's tallest statue which was erected by the Indian government at a cost of US$420 million, was dedicated to him on 31 October 2018 and is approximately 182 metres (597 ft) in height.[8]

Early life and background

[edit]Sardar Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel,[9][10] one of the six children of Jhaverbhai Patel and Ladba, was born in Nadiad, Gujarat.[11] Patel's date of birth was never officially recorded; Patel entered it as 31 October on his matriculation examination papers.[12] He belonged to the Patidars, specifically the Leva Patel community of Central Gujarat; although after his fame, both Leva Patel and Kadava Patidar have claimed him as one of their own.[13]

Patel travelled to attend schools in Nadiad, Petlad, and Borsad, living self-sufficiently with other boys. He reputedly cultivated a stoic character. A popular anecdote recounts that he lanced his own painful boil without hesitation, even as the barber charged with doing it trembled.[14] When Patel passed his matriculation at the relatively late age of 22, he was generally regarded by his elders as an unambitious man destined for a commonplace job. Patel himself, though, harboured a plan to study to become a lawyer, work and save funds, travel to England, and become a barrister.[15] Patel spent years away from his family, studying on his own with books borrowed from other lawyers, passing his examinations within two years. Fetching his wife Jhaverba from her parents' home, Patel set up his household in Godhra and was called to the bar. During the many years it took him to save money, Patel – now an advocate – earned a reputation as a fierce and skilled lawyer. The couple had a daughter, Maniben, in 1903 and a son, Dahyabhai, in 1905. Patel also cared for a friend suffering from the Bubonic plague when it swept across Gujarat. When Patel himself came down with the disease, he immediately sent his family to safety, left his home, and moved into an isolated house in Nadiad (by other accounts, Patel spent this time in a dilapidated temple); there, he recovered slowly.[16]

Patel practised law in Godhra, Borsad, and Anand while taking on the financial burdens of his homestead in Karamsad. Patel was the first chairman and founder of "Edward Memorial High School" Borsad, today known as Jhaverbhai Dajibhai Patel High School. When he had saved enough for his trip to England and applied for a pass and a ticket, they were addressed to "V. J. Patel", at the home of his elder brother Vithalbhai, who had the same initials as Vallabhai. Having once nurtured a similar hope to study in England, Vithalbhai remonstrated his younger brother, saying that it would be disreputable for an older brother to follow his younger brother. In keeping with concerns for his family's honour, Patel allowed Vithalbhai to go in his place.[17]

In 1909 Patel's wife Jhaverba was hospitalised in Bombay (present-day Mumbai) to undergo major surgery for cancer. Her health suddenly worsened and, despite successful emergency surgery, she died in the hospital. Patel was given a note informing him of his wife's demise as he was cross-examining a witness in court. According to witnesses, Patel read the note, pocketed it, and continued his cross-examination and won the case. He broke the news to others only after the proceedings had ended.[18] Patel decided against marrying again. He raised his children with the help of his family and sent them to English-language schools in Bombay. At the age of 36, he journeyed to England and enrolled at the Middle Temple in London. Completing a 36-month course in 30 months, Patel finished at the top of his class despite having had no previous college background.[19]

Returning to India, Patel settled in Ahmedabad and became one of the city's most successful barristers. Wearing European-style clothes and sporting urbane mannerisms, he became a skilled bridge player. Patel nurtured ambitions to expand his practice and accumulate great wealth and to provide his children with modern education. He had made a pact with his brother Vithalbhai to support his entry into politics in the Bombay Presidency, while Patel remained in Ahmedabad to provide for the family.[20][21]

Fight for independence

[edit]In September 1917, Patel delivered a speech in Borsad, encouraging Indians nationwide to sign Gandhi's petition demanding Swaraj – self-rule – from Britain. A month later, he met Gandhi for the first time at the Gujarat Political Conference in Godhra. On Gandhi's encouragement, Patel became the secretary of the Gujarat Sabha, a public body that would become the Gujarati arm of the Indian National Congress. Patel now energetically fought against veth – the forced servitude of Indians to Europeans – and organised relief efforts in the wake of plague and famine in Kheda.[22] The Kheda peasants' plea for exemption from taxation had been turned down by British authorities. Gandhi endorsed waging a struggle there, but could not lead it himself due to his activities in Champaran. When Gandhi asked for a Gujarati activist to devote himself completely to the assignment, Patel volunteered, much to Gandhi's delight.[23] Though his decision was made on the spot, Patel later said that his desire and commitment came after intense personal contemplation, as he realised he would have to abandon his career and material ambitions.[24]

Satyagraha in Gujarat

[edit]Supported by Congress volunteers Narhari Parikh, Mohanlal Pandya, and Abbas Tyabji, Vallabhbhai Patel began a village-by-village tour in the Kheda district documenting grievances and asking villagers for their support for a statewide revolt by refusing to pay taxes. Patel emphasised the potential hardships and the need for complete unity and non-violence from every village in the face of provocation.[25] When the revolt was launched and tax revenue withheld, the government sent police and intimidation squads to seize property, including confiscating barn animals and whole farms. Patel organised a network of volunteers to work with individual villages, helping them hide valuables and protect themselves against raids. Thousands of activists and farmers were arrested, but Patel was not. The revolt evoked sympathy and admiration across India, including among pro-British Indian politicians. The government agreed to negotiate with Patel and decided to suspend the payment of taxes for a year, even scaling back the rate. Patel emerged as a hero to Gujaratis.[26] In 1920 he was elected president of the newly formed Gujarat Pradesh Congress Committee; he would serve as its president until 1945.[citation needed]

Patel supported Gandhi's Non-cooperation movement and toured the state to recruit more than 300,000 members and raise over Rs. 1.5 million in funds.[27] Helping organise bonfires in Ahmedabad in which British goods were burned, Patel threw in all his English-style clothes. Along with his daughter Mani and son Dahya, he switched completely to wearing khadi, the locally produced cotton clothing. Patel also supported Gandhi's controversial suspension of resistance in the wake of the Chauri Chaura incident. In Gujarat, he worked extensively in the following years against alcoholism, untouchability, and caste discrimination, as well as for the empowerment of women. In the Congress, he was a resolute supporter of Gandhi against his Swarajist critics. Patel was elected Ahmedabad's municipal president in 1922, 1924, and 1927. During his terms, he oversaw improvements in infrastructure: the supply of electricity was increased, and drainage and sanitation systems were extended throughout the city. The school system underwent major reforms. He fought for the recognition and payment of teachers employed in schools established by nationalists (independent of British control) and even took on sensitive Hindu–Muslim issues.[28] Patel personally led relief efforts in the aftermath of the torrential rainfall of 1927 that caused major floods in the city and in the Kheda district, and great destruction of life and property. He established refugee centres across the district, mobilised volunteers, and arranged for supplies of food, medicines, and clothing, as well as emergency funds from the government and the public.[29]

When Gandhi was in prison, Patel was asked by Members of Congress to lead the satyagraha in Nagpur in 1923 against a law banning the raising of the Indian flag. He organised thousands of volunteers from all over the country to take part in processions of people violating the law. Patel negotiated a settlement obtaining the release of all prisoners and allowing nationalists to hoist the flag in public. Later that year, Patel and his allies uncovered evidence suggesting that the police were in league with a local dacoit (criminal) gang related to Devar Baba in the Borsad taluka even as the government prepared to levy a major tax for fighting dacoits in the area. More than 6,000 villagers assembled to hear Patel speak in support of proposed agitation against the tax, which was deemed immoral and unnecessary. He organised hundreds of Congressmen, sent instructions, and received information from across the district. Every village in the taluka resisted payment of the tax and prevented the seizure of property and land. After a protracted struggle, the government withdrew the tax. Historians believe that one of Patel's key achievements was the building of cohesion and trust amongst the different castes and communities, which had been divided along socio-economic lines.[30]

In April 1928, Patel returned to the independence struggle from his municipal duties in Ahmedabad when Bardoli suffered from a serious double predicament of a famine and a steep tax hike. The revenue hike was steeper than it had been in Kheda even though the famine covered a large portion of Gujarat. After cross-examining and talking to village representatives, emphasising the potential hardship and need for non-violence and cohesion, Patel initiated the struggle with a complete denial of taxes.[31] Patel organised volunteers, camps, and an information network across affected areas. The revenue refusal was stronger than in Kheda, and many sympathy satyagrahas were undertaken across Gujarat. Despite arrests and seizures of property and land, the struggle intensified. The situation came to a head in August, when, through sympathetic intermediaries, he negotiated a settlement that included repealing the tax hike, reinstating village officials who had resigned in protest, and returning seized property and land. It was by the women of Bardoli, during the struggle and after the Indian National Congress victory in that area, that Patel first began to be referred to as Sardar (or chief).[32]

Fundamental Rights and Economic Policy: 1931

[edit]Under the chairmanship of Sardar Patel, the "Fundamental Rights and Economic Policy" resolution was passed by the Congress in 1931.

As Gandhi embarked on the Dandi Salt March, Patel was arrested in the village of Ras and was put on trial without witnesses, with no lawyer or journalists allowed to attend. Patel's arrest and Gandhi's subsequent arrest caused the Salt Satyagraha to greatly intensify in Gujarat. Districts across Gujarat launched an anti-tax rebellion until and unless Patel and Gandhi were released.[33] Once released, Patel served as interim Congress president, but was re-arrested while leading a procession in Bombay. After the signing of the Gandhi–Irwin Pact, Patel was elected president of Congress for its 1931 session in Karachi. Here the Congress ratified the pact and committed itself to the defence of fundamental rights and civil liberties. It advocated the establishment of a secular nation with a minimum wage and the abolition of untouchability and serfdom. Patel used his position as Congress president to organise the return of confiscated land to farmers in Gujarat.[34] Upon the failure of the Round Table Conference in London, Gandhi and Patel were arrested in January 1932 when the struggle re-opened, and imprisoned in the Yeravda Central Jail. During this term of imprisonment, Patel and Gandhi grew close to each other, and the two developed a close bond of affection, trust, and frankness. Their mutual relationship could be described as that of an elder brother (Gandhi) and his younger brother (Patel). Despite having arguments with Gandhi, Patel respected his instincts and leadership. In prison, the two discussed national and social issues, read Hindu epics, and cracked jokes. Gandhi taught Patel Sanskrit. Gandhi's secretary, Mahadev Desai, kept detailed records of conversations between Gandhi and Patel.[35] When Gandhi embarked on a fast-unto-death protesting the separate electorates allocated for untouchables, Patel looked after Gandhi closely and himself refrained from partaking of food.[36] Patel was later moved to a jail in Nasik, and refused a British offer for a brief release to attend the cremation of his brother Vithalbhai, who had died in October 1933. He was finally released in July 1934.[citation needed]

Patel's position at the highest level in the Congress was largely connected with his role from 1934 onwards (when the Congress abandoned its boycott of elections) in the party organisation. Based at an apartment in Bombay, he became the Congress's main fundraiser and chairman of its Central Parliamentary Board, playing the leading role in selecting and financing candidates for the 1934 elections to the Central Legislative Assembly in New Delhi and for the provincial elections of 1936.[37] In addition to collecting funds and selecting candidates, he also determined the Congress's stance on issues and opponents.[38] Not contesting a seat for himself, Patel nevertheless guided Congressmen elected in the provinces and at the national level. In 1935 Patel underwent surgery for haemorrhoids, yet continued to direct efforts against the plague in Bardoli and again when a drought struck Gujarat in 1939. Patel guided the Congress ministries that had won power across India with the aim of preserving party discipline – Patel feared that the British government would take advantage of opportunities to create conflict among elected Congressmen, and he did not want the party to be distracted from the goal of complete independence.[39] Patel clashed with Nehru, opposing declarations of the adoption of socialism at the 1936 Congress session, which he believed was a diversion from the main goal of achieving independence. In 1938 Patel organised rank and file opposition to the attempts of then-Congress president Subhas Chandra Bose to move away from Gandhi's principles of non-violent resistance. Patel saw Bose as wanting more power over the party. He led senior Congress leaders in a protest that resulted in Bose's resignation. But criticism arose from Bose's supporters, socialists, and other Congressmen that Patel himself was acting in an authoritarian manner in his defence of Gandhi's authority.[citation needed]

Legal Battle with Subhas Chandra Bose

[edit]Patel's elder brother Vithalbhai Patel, died in Geneva on 22 October 1933.[40]

Vithalbhai and Bose had been highly critical of Gandhi's leadership during their travels in Europe. "By the time Vithalbhai died in October 1933, Bose had become his primary caregiver. On his deathbed he left a will of sorts, bequeathing three-quarters of his money to Bose to use in promoting India's cause in other countries. When Patel saw a copy of the letter in which his brother had left a majority of his estate to Bose, he asked a series of questions: Why was the letter not attested by a doctor? Had the original paper been preserved? Why were the witnesses to that letter all men from Bengal and none of the many other veteran freedom activists and supporters of the Congress who had been present at Geneva where Vithalbhai had died? Patel may even have doubted the veracity of the signature on the document. The case went to the court and after a legal battle that lasted more than a year, the courts judged that Vithalbhai's estate could only be inherited by his legal heirs, that is, his family. Patel promptly handed the money over to the Vithalbhai Memorial Trust."[41]

Quit India movement

[edit]On the outbreak of World War II, Patel supported Nehru's decision to withdraw the Congress from central and provincial legislatures, contrary to Gandhi's advice, as well as an initiative by senior leader Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari to offer Congress's full support to Britain if it promised Indian independence at the end of the war and installed a democratic government right away. Gandhi had refused to support Britain on the grounds of his moral opposition to war, while Subhash Chandra Bose was in militant opposition to the British. The British government rejected Rajagopalachari's initiative, and Patel embraced Gandhi's leadership again.[42] He participated in Gandhi's call for individual disobedience, and was arrested in 1940 and imprisoned for nine months. He also opposed the proposals of the Cripps mission in 1942. Patel lost more than twenty pounds during his period in jail.[citation needed]

While Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and Maulana Azad initially criticised Gandhi's proposal for an all-out campaign of civil disobedience to force the British to grant Indian independence, Patel was its most fervent supporter. Arguing that the British would retreat from India as they had from Singapore and Burma, Patel urged that the campaign start without any delay.[43] Though feeling that the British would not leave immediately, Patel favoured an all-out rebellion that would galvanise the Indian people, who had been divided in their response to the war. In Patel's view, such a rebellion would force the British to concede that continuation of colonial rule had no support in India, and thus speed the transfer of power to Indians.[44] Believing strongly in the need for revolt, Patel stated his intention to resign from the Congress if the revolt were not approved.[45] Gandhi strongly pressured the AICC to approve an all-out campaign of civil disobedience, and the AICC approved the campaign on 7 August 1942. Though Patel's health had suffered during his stint in jail, he gave emotional speeches to large crowds across India,[46] asking them to refuse to pay taxes and to participate in civil disobedience, mass protests, and a shutdown of all civil services. He raised funds and prepared a second tier of command as a precaution against the arrest of national leaders.[47] Patel made a climactic speech to more than 100,000 people gathered at Gowalia Tank in Bombay on 7 August:

The Governor of Burma boasts in London that they left Burma only after reducing everything to dust. So you promise the same thing to India? ... You refer in your radio broadcasts and newspapers to the government established in Burma by Japan as a puppet government? What sort of government do you have in Delhi now?...When France fell before the Nazi onslaught, in the midst of total war, Mr. Churchill offered union with England to the French. That was indeed a stroke of inspired statesmanship. But when it comes to India? Oh no! Constitutional changes in the midst of a war? Absolutely unthinkable ... The objective this time is to free India before the Japanese can come and be ready to fight them if they come. They will round up the leaders, round up all. Then it will be the duty of every Indian to put forth his utmost effort—within non-violence. No source is to be left untapped; no weapon untried. This is going to be the opportunity of a lifetime.[48]

Historians believe that Patel's speech was instrumental in electrifying nationalists, who up to then had been sceptical of the proposed rebellion. Patel's organising work in this period is credited by historians with ensuring the success of the rebellion across India.[5] Patel was arrested on 9 August and was imprisoned with the entire Congress Working Committee from 1942 to 1945 at the fort in Ahmednagar. Here he spun cloth, played bridge, read a large number of books, took long walks, and practised gardening. He also provided emotional support to his colleagues while awaiting news and developments from the outside.[49] Patel was deeply pained at the news of the deaths of Mahadev Desai and Kasturba Gandhi later that year.[50] But Patel wrote in a letter to his daughter that he and his colleagues were experiencing "fullest peace" for having done "their duty".[51] Even though other political parties had opposed the struggle and the British colonial government had responded by imprisoning most of the leaders of Congress, the Quit India movement was "by far the most serious rebellion since that of 1857", as the viceroy cabled to Winston Churchill. More than 100,000 people were arrested and numerous protestors were killed in violent confrontations with the Indian Imperial Police. Strikes, protests, and other revolutionary activities had broken out across India.[52] When Patel was released on 15 June 1945, he realised that the British government was preparing proposals to transfer power to India.[citation needed]

Partition and independence

[edit]In the 1946 Indian provincial elections, the Congress won a large majority of the elected seats, dominating the Hindu electorate. However the Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah won a large majority of Muslim electorate seats. The League had resolved in 1940 to demand Pakistan – an independent state for Muslims – and was a fierce critic of the Congress. The Congress formed governments in all provinces save Sindh, Punjab, and Bengal, where it entered into coalitions with other parties.

Cabinet mission and partition

[edit]When the British mission proposed two plans for transfer of power, there was considerable opposition within the Congress to both. The plan of 16 May 1946 proposed a loose federation with extensive provincial autonomy, and the "grouping" of provinces based on religious-majority. The plan of 16 May 1946 proposed the partition of India on religious lines, with over 565 princely states free to choose between independence or accession to either dominion. The League approved both plans while the Congress flatly rejected the proposal of 16 May. Gandhi criticised the 16 May proposal as being inherently divisive, but Patel, realising that rejecting the proposal would mean that only the League would be invited to form a government, lobbied the Congress Working Committee hard to give its assent to the 16 May proposal. Patel engaged in discussions with the British envoys Sir Stafford Cripps and Lord Pethick-Lawrence and obtained an assurance that the "grouping" clause would not be given practical force, Patel converted Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, and Rajagopalachari to accept the plan. When the League retracted its approval of the 16 May plan, the viceroy Lord Wavell invited the Congress to form the government. Under Nehru, who was styled the "Vice President of the Viceroy's Executive Council", Patel took charge of the departments of home affairs and information and broadcasting. He moved into a government house on Aurangzeb Road in Delhi, which would be his home until his death in 1950.[53]

Vallabhbhai Patel was one of the first Congress leaders to accept the partition of India as a solution to the rising Muslim separatist movement led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He had been outraged by Jinnah's Direct Action campaign, which had provoked communal violence across India, and by the viceroy's vetoes of his home department's plans to stop the violence on the grounds of constitutionality. Patel severely criticised the viceroy's induction of League ministers into the government, and the revalidation of the grouping scheme by the British government without Congress's approval. Although further outraged at the League's boycott of the assembly and non-acceptance of the plan of 16 May despite entering government, he was also aware that Jinnah did enjoy popular support amongst Muslims, and that an open conflict between him and the nationalists could degenerate into a Hindu-Muslim civil war of disastrous consequences. The continuation of a divided and weak central government would, in Patel's mind, result in the wider fragmentation of India by encouraging more than 600 princely states towards independence.[54] In December 1946 and January 1947, Patel worked with civil servant V. P. Menon on the latter's suggestion for a separate dominion of Pakistan created out of Muslim-majority provinces. Communal violence in Bengal and Punjab in January and March 1947 further convinced Patel of the soundness of partition. Patel, a fierce critic of Jinnah's demand that the Hindu-majority areas of Punjab and Bengal be included in a Muslim state, obtained the partition of those provinces, thus blocking any possibility of their inclusion in Pakistan. Patel's decisiveness on the partition of Punjab and Bengal had won him many supporters and admirers amongst the Indian public, which had tired of the League's tactics, but he was criticised by Gandhi, Nehru, secular Muslims, and socialists for a perceived eagerness to do so. When Lord Louis Mountbatten formally proposed the plan on 3 June 1947, Patel gave his approval and lobbied Nehru and other Congress leaders to accept the proposal. Knowing Gandhi's deep anguish regarding proposals of partition, Patel engaged him in frank discussion in private meetings over what he saw as the practical unworkability of any Congress–League coalition, the rising violence, and the threat of civil war. At the All India Congress Committee meeting called to vote on the proposal, Patel said:

I fully appreciate the fears of our brothers from [the Muslim-majority areas]. Nobody likes the division of India and my heart is heavy. But the choice is between one division and many divisions. We must face facts. We cannot give way to emotionalism and sentimentality. The Working Committee has not acted out of fear. But I am afraid of one thing, that all our toil and hard work of these many years might go waste or prove unfruitful. My nine months in office has completely disillusioned me regarding the supposed merits of the Cabinet Mission Plan. Except for a few honourable exceptions, Muslim officials from the top down to the chaprasis (peons or servants) are working for the League. The communal veto given to the League in the Mission Plan would have blocked India's progress at every stage. Whether we like it or not, de facto Pakistan already exists in the Punjab and Bengal. Under the circumstances I would prefer a de jure Pakistan, which may make the League more responsible. Freedom is coming. We have 75 to 80 percent of India, which we can make strong with our own genius. The League can develop the rest of the country.[55]

After Gandhi rejected and Congress approved the plan, Patel represented India on the Partition Council,[56][57] where he oversaw the division of public assets, and selected the Indian council of ministers with Nehru.[58] However, neither Patel nor any other Indian leader had foreseen the intense violence and population transfer that would take place with partition. Patel took the lead in organising relief and emergency supplies, establishing refugee camps, and visiting the border areas with Pakistani leaders to encourage peace. Despite these efforts, the death toll is estimated at between 500,000 and 1 million people.[59] The estimated number of refugees in both countries exceeds 15 million.[60] Understanding that Delhi and Punjab policemen, accused of organising attacks on Muslims, were personally affected by the tragedies of partition, Patel called out the Indian Army with South Indian regiments to restore order, imposing strict curfews and shoot-on-sight orders. Visiting the Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah area in Delhi, where thousands of Delhi Muslims feared attacks, he prayed at the shrine, visited the people, and reinforced the presence of police. He suppressed from the press reports of atrocities in Pakistan against Hindus and Sikhs to prevent retaliatory violence. Establishing the Delhi Emergency Committee to restore order and organising relief efforts for refugees in the capital, Patel publicly warned officials against partiality and neglect. When reports reached Patel that large groups of Sikhs were preparing to attack Muslim convoys heading for Pakistan, Patel hurried to Amritsar and met Sikh and Hindu leaders. Arguing that attacking helpless people was cowardly and dishonourable, Patel emphasised that Sikh actions would result in further attacks against Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan. He assured the community leaders that if they worked to establish peace and order and guarantee the safety of Muslims, the Indian government would react forcefully to any failures of Pakistan to do the same. Additionally, Patel addressed a massive crowd of approximately 200,000 refugees who had surrounded his car after the meetings:

Here, in this same city, the blood of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims mingled in the bloodbath of Jallianwala Bagh. I am grieved to think that things have come to such a pass that no Muslim can go about in Amritsar and no Hindu or Sikh can even think of living in Lahore. The butchery of innocent and defenceless men, women and children does not behove brave men ... I am quite certain that India's interest lies in getting all her men and women across the border and sending out all Muslims from East Punjab. I have come to you with a specific appeal. Pledge the safety of Muslim refugees crossing the city. Any obstacles or hindrances will only worsen the plight of our refugees who are already performing prodigious feats of endurance. If we have to fight, we must fight clean. Such a fight must await an appropriate time and conditions and you must be watchful in choosing your ground. To fight against the refugees is no fight at all. No laws of humanity or war among honourable men permit the murder of people who have sought shelter and protection. Let there be truce for three months in which both sides can exchange their refugees. This sort of truce is permitted even by laws of war. Let us take the initiative in breaking this vicious circle of attacks and counter-attacks. Hold your hands for a week and see what happens. Make way for the refugees with your own force of volunteers and let them deliver the refugees safely at our frontier.[61]

Following his dialogue with community leaders and his speech, no further attacks occurred against Muslim refugees, and a wider peace and order was soon re-established over the entire area. However, Patel was criticised by Nehru, secular Muslims, and Gandhi over his alleged wish to see Muslims from other parts of India depart. While Patel vehemently denied such allegations, the acrimony with Maulana Azad and other secular Muslim leaders increased when Patel refused to dismiss Delhi's Sikh police commissioner, who was accused of discrimination. Hindu and Sikh leaders also accused Patel and other leaders of not taking Pakistan sufficiently to task over the attacks on their communities there, and Muslim leaders further criticised him for allegedly neglecting the needs of Muslims leaving for Pakistan, and concentrating resources for incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees. Patel clashed with Nehru and Azad over the allocation of houses in Delhi vacated by Muslims leaving for Pakistan; Nehru and Azad desired to allocate them for displaced Muslims, while Patel argued that no government professing secularism must make such exclusions. However, Patel was publicly defended by Gandhi and received widespread admiration and support for speaking frankly on communal issues and acting decisively and resourcefully to quell disorder and violence.[62]

Political integration of independent India

[edit]

As the first Home Minister, Patel played one of the major role in the integration of the princely states into the Indian federation.[63] This achievement formed the cornerstone of Patel's popularity in the post-independence era. He is, in this regard, compared to Otto von Bismarck who unified the many German states in 1871.[64] Under the plan of 3 June, more than 565 princely states were given the option of joining either India or Pakistan, or choosing independence. Indian nationalists and large segments of the public feared that if these states did not accede, most of the people and territory would be fragmented. The Congress, as well as senior British officials, considered Patel the best man for the task of achieving conquest of the princely states by the Indian dominion. Gandhi had said to Patel, "The problem of the States is so difficult that you alone can solve it."[65] Patel was considered a statesman of integrity with the practical acumen and resolve to accomplish a monumental task. He asked V. P. Menon, a senior civil servant with whom he had worked on the partition of India, to become his right-hand man as chief secretary of the States Ministry. On 6 August 1947, Patel began lobbying the princes, attempting to make them receptive towards dialogue with the future government and forestall potential conflicts. Patel used social meetings and unofficial surroundings to engage most of the monarchs, inviting them to lunch and tea at his home in Delhi. At these meetings, Patel explained that there was no inherent conflict between the Congress and the princely order. Patel invoked the patriotism of India's monarchs, asking them to join in the independence of their nation and act as responsible rulers who cared about the future of their people. He persuaded the princes of 565 states of the impossibility of independence from the Indian republic, especially in the presence of growing opposition from their subjects. He proposed favourable terms for the merger, including the creation of privy purses for the rulers' descendants. While encouraging the rulers to act out of patriotism, Patel did not rule out force. Stressing that the princes would need to accede to India in good faith, he set a deadline of 15 August 1947 for them to sign the instrument of accession document. All but three of the states willingly merged into the Indian union; only Jammu and Kashmir, Junagadh, and Hyderabad did not fall into his basket.[66]

Junagadh was especially important to Patel, since it was in his home state of Gujarat. It was also important because in this Kathiawar district was the ultra-rich Somnath temple (which in the 11th century had been plundered by Mahmud of Ghazni, who damaged the temple and its idols to rob it of its riches, including emeralds, diamonds, and gold). Under pressure from Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, the Nawab had acceded to Pakistan. It was, however, quite far from Pakistan, and 80% of its population was Hindu. Patel combined diplomacy with force, demanding that Pakistan annul the accession, and that the Nawab accede to India. He sent the Army to occupy three principalities of Junagadh to show his resolve. Following widespread protests and the formation of a civil government, or Aarzi Hukumat, both Bhutto and the Nawab fled to Karachi, and under Patel's orders the Indian Army and police units marched into the state. A plebiscite organised later produced a 99.5% vote for merger with India.[67] In a speech at the Bahauddin College in Junagadh following the latter's take-over, Patel emphasised his feeling of urgency on Hyderabad, which he felt was more vital to India than Kashmir:

If Hyderabad does not see the writing on the wall, it goes the way Junagadh has gone. Pakistan attempted to set off Kashmir against Junagadh. When we raised the question of settlement in a democratic way, they (Pakistan) at once told us that they would consider it if we applied that policy to Kashmir. Our reply was that we would agree to Kashmir if they agreed to Hyderabad.[67]

Hyderabad was the largest of the princely states, and it included parts of present-day Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Maharashtra states. Its ruler, the Nizam Osman Ali Khan, was a Muslim, although over 80% of its people were Hindu. The Nizam sought independence or accession with Pakistan. Muslim forces loyal to Nizam, called the Razakars, under Qasim Razvi, pressed the Nizam to hold out against India, while organising attacks on people on Indian soil. Even though a Standstill Agreement was signed due to the desperate efforts of Lord Mountbatten to avoid a war, the Nizam rejected deals and changed his positions.[68] On September 7, Jawaharlal Nehru gave ultimatum to Nizam, demanding ban on the Razakars and return of Indian troops to Secunderabad.[69][70] Pakistan foreign minister Muhammad Zafarullah Khan warned India against this ultimatum.[71] The invasion of Hyderabad was then launched on 13 September, after the death of Jinnah on 11 September.[72][73] After the defeat of Razakars, the Nizam signed an instrument of accession, joining India.[74]

Leading India

[edit]The Governor-General of India, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, along with Nehru and Patel, formed the "triumvirate" that ruled India from 1948 to 1950. Prime Minister Nehru was intensely popular with the masses, but Patel enjoyed the loyalty and the faith of rank and file Congressmen, state leaders, and India's civil servants. Patel was a senior leader in the Constituent Assembly of India and was responsible in large measure for shaping India's constitution.[75]

Patel was the chairman of the committees responsible for minorities, tribal and excluded areas, fundamental rights, and provincial constitutions. Patel piloted a model constitution for the provinces in the Assembly, which contained limited powers for the state governor, who would defer to the president – he clarified it was not the intention to let the governor exercise power that could impede an elected government.[75] He worked closely with Muslim leaders to end separate electorates and the more potent demand for reservation of seats for minorities.[76] His intervention was key to the passage of two articles that protected civil servants from political involvement and guaranteed their terms and privileges.[75] He was also instrumental in the founding the Indian Administrative Service and the Indian Police Service, and for his defence of Indian civil servants from political attack; he is known as the "patron saint" of India's services. When a delegation of Gujarati farmers came to him citing their inability to send their milk production to the markets without being fleeced by intermediaries, Patel exhorted them to organise the processing and sale of milk by themselves, and guided them to create the Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers' Union Limited, which preceded the Amul milk products brand. Patel also pledged the reconstruction of the ancient but dilapidated Somnath Temple in Saurashtra. He oversaw the restoration work and the creation of a public trust, and pledged to dedicate the temple upon the completion of work (the work was completed after his death and the temple was inaugurated by the first President of India, Dr. Rajendra Prasad).

When the Pakistani invasion of Kashmir began in September 1947, Patel immediately wanted to send troops into Kashmir. But, agreeing with Nehru and Mountbatten, he waited until Kashmir's monarch had acceded to India. Patel then oversaw India's military operations to secure Srinagar and the Baramulla Pass, and the forces retrieved much territory from the invaders. Patel, along with Defence Minister Baldev Singh, administered the entire military effort, arranging for troops from different parts of India to be rushed to Kashmir and for a major military road connecting Srinagar to Pathankot to be built in six months.[77] Patel strongly advised Nehru against going for arbitration to the United Nations, insisting that Pakistan had been wrong to support the invasion and the accession to India was valid. He did not want foreign interference in a bilateral affair. Patel opposed the release of Rs. 550 million to the Government of Pakistan, convinced that the money would go to finance the war against India in Kashmir. The Cabinet had approved his point but it was reversed when Gandhi, who feared an intensifying rivalry and further communal violence, went on a fast-unto-death to obtain the release. Patel, though not estranged from Gandhi, was deeply hurt at the rejection of his counsel and a Cabinet decision.[78]

In 1949 a crisis arose when the number of Hindu refugees entering West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura from East Pakistan climbed to over 800,000. The refugees in many cases were being forcibly evicted by Pakistani authorities, and were victims of intimidation and violence.[79] Nehru invited Liaquat Ali Khan, Prime Minister of Pakistan, to find a peaceful solution. Despite his aversion, Patel reluctantly met Khan and discussed the matter. Patel strongly criticised Nehru's plan to sign a pact that would create minority commissions in both countries and pledge both India and Pakistan to a commitment to protect each other's minorities.[80] Syama Prasad Mookerjee and K. C. Neogy, two Bengali ministers, resigned, and Nehru was intensely criticised in West Bengal for allegedly appeasing Pakistan. The pact was immediately in jeopardy. Patel, however, publicly came to Nehru's aid. He gave emotional speeches to members of Parliament, and the people of West Bengal, and spoke with scores of delegations of Congressmen, Hindus, Muslims, and other public interest groups, persuading them to give peace a final effort.[81]

In April 2015 the Government of India declassified surveillance reports suggesting that Patel, while Home Minister, and Nehru were among officials involved in alleged government-authorised spying on the family of Subhas Chandra Bose.[82]

Father of All India Services

[edit]There is no alternative to this administrative system... The Union will go, you will not have a united India if you do not have good All-India Service which has the independence to speak out its mind, which has sense of security that you will standby your work... If you do not adopt this course, then do not follow the present Constitution. Substitute something else... these people are the instrument. Remove them and I see nothing but a picture of chaos all over the country.

He was also instrumental in the creation of the All India Services which he described as the country's "Steel Frame". In his address to the probationers of these services, he asked them to be guided by the spirit of service in day-to-day administration. He reminded them that the ICS was no-longer neither Imperial, nor civil, nor imbued with any spirit of service after Independence. His exhortation to the probationers to maintain utmost impartiality and incorruptibility of administration is as relevant today as it was then. "A civil servant cannot afford to, and must not, take part in politics. Nor must he involve himself in communal wrangles. To depart from the path of rectitude in either of these respects is to debase public service and to lower its dignity," he had cautioned them on 21 April 1947.[86]

He, more than anyone else in post-independence India, realised the crucial role that civil services play in administering a country, in not merely maintaining law and order, but running the institutions that provide the binding cement to a society. He, more than any other contemporary of his, was aware of the needs of a sound, stable administrative structure as the lynchpin of a functioning polity. The present-day all-India administrative services owe their origin to the man's sagacity and thus he is regarded as Father of modern All India Services.[87]

Relations with Gandhi and Nehru

[edit]

Patel was intensely loyal to Gandhi, and both he and Nehru looked to him to arbitrate disputes. However, Nehru and Patel sparred over national issues.[88] When Nehru asserted control over Kashmir policy, Patel objected to Nehru's sidelining his home ministry's officials.[89] Nehru was offended by Patel's decision-making regarding the states' integration, having consulted neither him nor the Cabinet. Patel asked Gandhi to relieve him of his obligation to serve, believing that an open political battle would hurt India. After much personal deliberation and contrary to Patel's prediction, Gandhi on 30 January 1948 told Patel not to leave the government. A free India, according to Gandhi, needed both Patel and Nehru. Patel was the last man to privately talk with Gandhi, who was assassinated just minutes after Patel's departure.[90] At Gandhi's wake, Nehru and Patel embraced each other and addressed the nation together. Patel gave solace to many associates and friends and immediately moved to forestall any possible violence.[91] Within two months of Gandhi's death, Patel suffered a major heart attack; the timely action of his daughter, his secretary, and a nurse saved Patel's life. Speaking later, Patel attributed the attack to the grief bottled up due to Gandhi's death.[92]

Criticism arose from the media and other politicians that Patel's home ministry had failed to protect Gandhi. Emotionally exhausted, Patel tendered a letter of resignation, offering to leave the government. Patel's secretary persuaded him to withhold the letter, seeing it as fodder for Patel's political enemies and political conflict in India.[93] However, Nehru sent Patel a letter dismissing any question of personal differences or desire for Patel's ouster. He reminded Patel of their 30-year partnership in the independence struggle and asserted that after Gandhi's death, it was especially wrong for them to quarrel. Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and other Congressmen publicly defended Patel. Moved, Patel publicly endorsed Nehru's leadership and refuted any suggestion of discord, and dispelled any notion that he sought to be prime minister.[93]

Nehru gave Patel a free hand in integrating the princely states into India.[63] Though the two committed themselves to joint leadership and non-interference in Congress party affairs, they sometimes would criticise each other in matters of policy, clashing on the issues of Hyderabad's integration and UN mediation in Kashmir. Nehru declined Patel's counsel on sending assistance to Tibet after its 1950 invasion by the People's Republic of China and on ejecting the Portuguese from Goa by military force.[94]

When Nehru pressured Rajendra Prasad to decline a nomination to become the first President of India in 1950 in favour of Rajagopalachari, he angered the party, which felt Nehru was attempting to impose his will. Nehru sought Patel's help in winning the party over, but Patel declined, and Prasad was duly elected. Nehru opposed the 1950 Congress presidential candidate Purushottam Das Tandon, a conservative Hindu leader, endorsing Jivatram Kripalani instead and threatening to resign if Tandon was elected. Patel rejected Nehru's views and endorsed Tandon in Gujarat, where Kripalani received not one vote despite hailing from that state himself.[95] Patel believed Nehru had to understand that his will was not law with the Congress, but he personally discouraged Nehru from resigning after the latter felt that the party had no confidence in him.[96]

Ban on RSS

[edit]The other is the R.S.S. I have made them an open offer. Change your plans, give up secrecy, respect the Constitution of India, show your loyalty to the (National Flag) and make us believe that we can trust your words. Whether they are friends or foes, and even if they are our own dear children, we are not going to allow them to play with fire so that the house may be set on fire. It would be criminal to allow young men to indulge in acts of violence and destruction..

In January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by Hindutva activist Nathuram Godse.[99] Following the assassination, many prominent leaders of the Hindu nationalist organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) were arrested, and the organisation was banned on 4 February 1948 by Patel. During the court proceedings in relation to the assassination Godse began claiming that he had left the organisation in 1946.[100] Vallabhbhai Patel had remarked that the "RSS men expressed joy and distributed sweets after Gandhi's death".[101]

The charged RSS leaders were acquitted of the conspiracy charge by the Supreme Court of India. Following his release in August 1948, Golwalkar wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to lift the ban on RSS. After Nehru replied that the matter was the responsibility of the Home Minister, Golwalkar consulted Vallabhai Patel regarding the same. Patel then demanded an absolute pre-condition that the RSS adopt a formal written constitution[102] and make it public, where Patel expected RSS to pledge its loyalty to the Constitution of India, accept the Tricolor as the National Flag of India, define the power of the head of the organisation, make the organisation democratic by holding internal elections, authorisation of their parents before enrolling the pre-adolescents into the movement, and to renounce violence and secrecy.[103][104][105]

Golwalkar launched a huge agitation against this demand during which he was imprisoned again. Later, a constitution was drafted for RSS, which, however, initially did not meet any of Patel's demands. After a failed attempt to agitate again, eventually the RSS's constitution was amended according to Patel's wishes with the exception of the procedure for selecting the head of the organisation and the enrolment of pre-adolescents. However, the organisation's internal democracy which was written into its constitution, remained a 'dead letter'.[106]

On 11 July 1949 the Government of India lifted the ban on the RSS by issuing a communique stating that the decision to lift the ban on the RSS had been taken in view of the RSS leader Golwalkar's undertaking to make the group's loyalty towards the Constitution of India and acceptance and respect towards the National Flag of India more explicit in the Constitution of the RSS, which was to be worked out in a democratic manner.[105][107]

Final years

[edit]In his twilight years, Patel was honoured by members of Parliament. He was awarded honorary doctorates of law by Nagpur University, the University of Allahabad and Banaras Hindu University in November 1948, subsequently receiving honorary doctorates from Osmania University in February 1949 and from Punjab University in March 1949.[108][109] Previously, Patel had been featured on the cover page of the January 1947 issue of Time magazine.[110]

On 29 March 1949 authorities lost radio contact with a Royal Indian Air Force de Havilland Dove carrying Patel, his daughter Maniben, and the Maharaja of Patiala from Delhi to Jaipur.[111] The pilot had been ordered to fly at a low altitude due to turbulence.[112] During the flight, loss of power in an engine caused the pilot to make an emergency landing in a desert area in Rajasthan.[112] Owing to the aircraft's flying at a low altitude, the pilot was unable to send a distress call with the aircraft's VHF radio, nor could he use his HF equipment as the crew lacked a trained signaller.[112] With all passengers safe, Patel and others tracked down a nearby village and local officials. A subsequent RIAF court of inquiry headed by Group Captain (later Air Chief Marshal and Chief of the Air Staff) Pratap Chandra Lal concluded the forced landing had been caused by fuel starvation.[111][112] When Patel returned to Delhi, thousands of Congressmen gave him a resounding welcome. In Parliament, MPs gave a long standing ovation to Patel, stopping proceedings for half an hour.[113]

Death

[edit]Patel's health declined rapidly through the summer of 1949. He later began coughing blood, whereupon Maniben began limiting his meetings and working hours and arranged for a personalised medical staff to begin attending to Patel. The then Chief Minister of West Bengal, Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy heard Patel make jokes about his impending end, and in a private meeting Patel admitted to his ministerial colleague N. V. Gadgil that he was not going to live much longer. Patel's health worsened after 2 November, when he began losing consciousness frequently and was confined to his bed. He was flown to Bombay on 12 December on advice from Dr Roy, to recuperate as his condition was deemed critical.[114] Nehru, Rajagopalachari, Rajendra Prasad, and Menon all came to see him off at the airport in Delhi. Patel was extremely weak and had to be carried onto the aircraft in a chair. In Bombay, large crowds gathered at Santacruz Airport to greet him. To spare him from this stress, the aircraft landed at Juhu Aerodrome, where Chief Minister B. G. Kher and Morarji Desai were present to receive him with a car belonging to the Governor of Bombay that took Vallabhbhai to Birla House.[115][116]

After suffering a massive heart attack (his second), Patel died on 15 December 1950 at Birla House in Bombay.[117] In an unprecedented and unrepeated gesture, on the day after his death more than 1,500 officers of India's civil and police services congregated to mourn at Patel's residence in Delhi and pledged "complete loyalty and unremitting zeal" in India's service.[118] Numerous governments and world leaders sent messages of condolence upon Patel's death, including Trygve Lie, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, President Sukarno of Indonesia, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan of Pakistan and Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the United Kingdom.[119]

In homage to Patel, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru declared a week of national mourning.[120] Patel's cremation was planned at Girgaum Chowpatty, but this was changed to Sonapur (now Marine Lines) when his daughter conveyed that it was his wish to be cremated like a common man in the same place as his wife and brother were earlier cremated. His cremation in Sonapur in Bombay was attended by a crowd of one million including Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajagopalachari and President Rajendra Prasad.[116][121][122]

Awards and honours

[edit] India:

India:

Bharat Ratna (1991, posthumous)

Bharat Ratna (1991, posthumous)

Legacy

[edit]

Sardar Patel is a widely celebrated Indian freedom fighter in India, as well as a respected leader. In his eulogy, delivered the day after Patel's death, Girija Shankar Bajpai, the Secretary-General of the Ministry of External Affairs, paid tribute to "a great patriot, a great administrator and a great man. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was all three, a rare combination in any historic epoch and in any country."[108] Bajpai lauded Patel for his achievements as a patriot and as an administrator, notably his vital role in securing India's stability in the aftermath of Independence and Partition:

...History holds many examples of the fruits of freedom squandered by lack of attention to stability and order, the twin foundations of society. Though a revolutionary in his fight against foreign rule, Sardar Patel was no believer in abrupt or violent change; progress by evolution was really his motto. And so, although in August 1947 power changed hands, and with it the spirit of the administration, the machinery of Government was preserved. As Home Minister and Minister for States, the Sardar had a double task, conservative in the good sense of the word, in what had been Provinces in the old India, creative in the Indian States. Neither was easy. To the ordinary stresses of a transition caused by the withdrawal of trained personnel which had wielded all power for a hundred years was added the strain of partition, and the immense human upheavals and suffering that followed it. The fate of our new State hung in the balance during those perilous months when millions moved across the new frontiers under conditions which are still vivid—indeed, too vivid—in our memories, and therefore, need not be described. That despite some oscillation the scales stayed steady was due not only to the faith of the people in its leaders, but to the firm will and strong hand of the new Home Minister.

Among Patel's surviving family, Maniben Patel lived in a flat in Bombay for the rest of her life following her father's death; she often led the work of the Sardar Patel Memorial Trust, which organises the prestigious annual Sardar Patel Memorial Lectures, and other charitable organisations. Dahyabhai Patel was a businessman who was elected to serve in the Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Indian Parliament) as an MP in the 1960s.[123]

Patel was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian honour, in 1991.[124] It was announced in 2014 that his birthday, 31 October, would become an annual national celebration known as Rashtriya Ekta Diwas (National Unity Day).[125] In 2012, Patel was ranked third in Outlook India's poll of the Greatest Indian.[126]

Patel's family home in Karamsad is preserved in his memory.[127] The Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial in Ahmedabad was established in 1980 at the Moti Shahi Mahal. It comprises a museum, a gallery of portraits and historical pictures, and a library containing important documents and books associated with Patel and his life. Amongst the exhibits are many of Patel's personal effects and relics from various periods of his personal and political life.[128]

Patel is the namesake of many public institutions in India. A major initiative to build dams, canals, and hydroelectric power plants in the Narmada River valley to provide a tri-state area with drinking water and electricity and to increase agricultural production was named the Sardar Sarovar. Patel is also the namesake of the Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology in Surat, Sardar Patel University, Sardar Patel High School, and the Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel University Of Agriculture and Technology in Meerut [U.P.]. India's national police training academy is also named after him.[129]

The international airport of Ahmedabad is named after him. Also the international cricket stadium of Ahmedabad (also known as the Motera Stadium) is named after him. A national cricket stadium in Navrangpura, Ahmedabad, used for national matches and events, is also named after him. The chief outer ring road encircling Ahmedabad is named S P Ring Road. The Gujarat government's institution for training government functionaries is named Sardar Patel Institute of Public Administration.[citation needed]

Rashtriya Ekta Diwas

[edit]Rashtriya Ekta Diwas (National Unity Day) was introduced by the Government of India and inaugurated by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. The intent is to pay tribute to Patel, who was instrumental in keeping India united. It is to be celebrated on 31 October every year as annual commemoration of the birthday of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, one of the founding leaders of Republic of India. The official statement for Rashtriya Ekta Diwas by the Home Ministry of India cites that the National Unity Day "will provide an opportunity to re-affirm the inherent strength and resilience of our nation to withstand the actual and potential threats to the unity, integrity and security of our country."[130]

National Unity Day celebrates the birthday of Patel because, during his term as Home Minister of India, he is credited for the integration of over 550 independent princely states into India from 1947 to 1949 by Independence Act (1947). He is known as the "Bismarck of India".[b] [131][132]

Commemorative stamps

[edit]Commemorative stamps released by India Post (by year) –

-

1965

-

1975

-

1997

-

2008

-

2016

-

A commemorative postage stamp on National Unity Day(31st October), Salute to the Unifier of India was issued on 31st October, 2016 by Department of Posts, Government of India.

Statue of Unity

[edit]

The Statue of Unity is a monument dedicated to Patel, located in the Indian state of Gujarat, facing the Narmada Dam, 3.2 km away from Sadhu Bet near Vadodara. At the height of 182 metres (597 feet), it is the world's tallest statue, exceeding the Spring Temple Buddha by 54 meters.[133] This statue and related structures are spread over 20,000 square meters and are surrounded by an artificial lake spread across 12 km and cost an estimated 29.8 billion rupees ($425m).[133] It was inaugurated by India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 31 October 2018, the 143rd anniversary of Patel's birth. The height of the statue in meters has been picked to match the total assembly constituencies in Gujarat.[134]

Other institutions and monuments

[edit]

- Sardar Patel Memorial Trust

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial, Ahmedabad

- Sardar Sarovar Dam, Gujarat

- Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology, Surat

- Sardar Patel University, Gujarat

- Sardar Patel University of Police, Security and Criminal Justice, Jodhpur

- Sardar Patel Institute of Technology, Vasad

- Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, New Delhi

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Police Academy, Hyderabad

- Sardar Patel College of Engineering, Mumbai

- Sardar Patel Institute of Technology, Mumbai

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Chowk in Katra Gulab Singh, Pratapgarh, Uttar Pradesh

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Institute of Technology, Vasad

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport, Ahmedabad

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Police Museum, Kollam

- Sardar Patel Stadium

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium, Ahmedabad

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel University of Agriculture and Technology

- Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute

- Statue of Unity[135]

In popular media

[edit]- 1947: Patel was featured on the cover of Time magazine.[136]

- 1976: Kantilal Rathod directed a documentary on Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

- 1982: In Richard Attenborough's Gandhi (1982), actor Saeed Jaffrey portrayed Patel.

- 1989: In a satirical novel The Great Indian Novel by Shashi Tharoor, the character of Vidur Hastinapuri is simultaneously based on Patel as well as the epic Mahabharata character Vidura.

- 1993: The biographical film Sardar was produced and directed by Ketan Mehta and featured noted Indian actor Paresh Rawal as Patel; it focused on Patel's leadership in the years leading up to independence, the partition of India, India's political integration and Patel's relationship with Gandhi and Nehru. The film was screened retrospectively on 12 August 2016 at the Independence Day Film Festival jointly presented by the Indian Directorate of Film Festivals and Ministry of Defense, commemorating the 70th Indian Independence Day.[137]

- 2000: Arun Sadekar plays Patel in Hey Ram – a film made by Kamal Haasan.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Sardar is a title of nobility that has been used to denote a chief or leader of a tribe or group.

- ^ Otto von Bismarck was known for the 1871 unification of Germany.

- ^ The statue of Sardar Vallabhai Patel is about 182 meters tall and located near the Narmada Dam, 3.2 km away on the river island called Bet, near Vadodara in Gujarat.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "How Vallabhbhai Patel, V P Menon, and Mountbatten unified India". 31 October 2017. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Gandhi, Rajmohan. Patel: a life (Biography). navjivan trust.

- ^ Lalchand, Kewalram (1977). The Indomitable Sardar. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 4.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

- ^ Brass, Paul R. (2004). Patel, Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai (1875/6–1950), Politician in India. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ^ a b Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 316.

- ^ Sanajaoba, N. (1991). Law and Society: Strategy for Public Choice, 2001. Mittal Publications. p. 223. ISBN 978-81-7099-271-4. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

The princely states had been wooed by Mountbatten, Patel and Nehru to join the Indian Dominion

- ^ "PM Modi pays rich tribute to 'iron man' Sardar Patel on his 141st birth anniversary", The Indian Express, 31 October 2016, archived from the original on 21 December 2022, retrieved 31 October 2016

- ^ "India unveils the world's tallest statue", BBC, 31 October 2018, archived from the original on 25 April 2021, retrieved 1 November 2018

- ^ "Vallabhai Patel". TheFreeDictionary.com (3rd ed.). The Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 1970–1979. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ David Argov, Vallabhbhai Patel at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel". Indian National Congress. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 3.

- ^ "Community power: how the Patels hold sway over Gujarat". Hindustan Times. 1 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 14.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 16.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 21.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 23.

- ^ "Education profiles of India's topfreedom fighters", The Indian Express, 12 May 2014, archived from the original on 15 October 2018, retrieved 31 October 2016

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 33.

- ^ "Famous Vegetarians – Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel". International Vegetarian Union. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 43.

- ^ Parikh 1953, p. 55.

- ^ Raojibhai Patel 1972, p. 39.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 65.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 91.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 134.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 138–141.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 119–125.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 168.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 193.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 206.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 226–229.

- ^ Brass, Paul R. (2004). Patel, Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai (1875/6–1950), Politician in India. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 248.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 266.

- ^ Patel, Gordhanbhai I. (1951). Vithalbhai Patel: Life and Times. Vol. 2. University of Bombay. p. 1228 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Sengupta 2018, p. [page needed].

- ^ Parikh 1956, pp. 434–436.

- ^ Parikh 1956, pp. 447–479.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Nandurkar 1981, p. 301.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 313.

- ^ Parikh 1956, pp. 474–477.

- ^ Parikh 1956, pp. 477–479.

- ^ Pattabhi 1946, p. 395.

- ^ Pattabhi 1946, p. 13.

- ^ Nandurkar 1981, p. 390.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 318.

- ^ Agrawal, Lion M.G. (2008). Freedom fighters of India (Volume 2). New Delhi: ISHA Books. p. 238.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 395–397.

- ^ Menon 1997, p. 385.

- ^ Balraj Krishna 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Menon 1997, p. 397.

- ^ Syed 2010, p. 18.

- ^ French, Patrick (1997). Liberty and Death: India's Journey to Independence and Division. London: HarperCollins. pp. 347–349.

- ^ "Postcolonial Studies" project, Department of English, Emory University. "The Partition of India". Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shankar 1974–1975, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Agrawal, Lion M.G. (2008). Freedom fighters of India (Volume 2). New Delhi: ISHA Books. pp. 241–242.

- ^ a b Buta Singh (July–December 2008). "Role of Sardar Patel in the Integration of Indian States". Calcutta Historical Journal. 28 (2): 65–78.

- ^ Balraj Krishna 2007.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 406.

- ^ Syed 2010, p. 21.

- ^ a b Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 438.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 480.

- ^ Siddiqi, A. (1960). Pakistan Seeks Security. Longmans, Green, Pakistan Branch. p. 21. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Benichou, L. D. (2000). From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State, 1938-1948. Orient Longman. p. 231. ISBN 978-81-250-1847-6. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Anthony Best, ed. (2003). British Documents on Foreign Affairs: Reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print. From 1946 through 1950. Asia 1948. E (Asia). Univ. Publ. of America. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-55655-768-2. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Hangloo, Rattan Lal; Murali, A. (2007). New Themes in Indian History: Art, Politics, Gender, Environment, and Culture. Black & White. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-81-89320-15-7.

- ^ "Vol. 17, No. 2, Second Quarter, 1964". Pakistan Horizon. 17 (2). Pakistan Institute of International Affairs: 169. 1964. ISSN 0030-980X. JSTOR 41392796. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Apparasu, Srinivasa Rao (16 September 2022). "How Hyd merger with Union unfolded". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Sardar Patel was the real architect of the Constitution". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2006.

- ^ Munshi 1967, p. 207.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 455.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 463.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 497.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 498.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 499.

- ^ "Nehru 'snooping' on Netaji's kin gives BJP anti-Congress ammunition". The Times of India. 11 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ "Discussion in Constituent Assembly on role of Indian Administrative Service". Parliament of India. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Sardar Patel's great contribution was the Indian Administrative Service". The Economic Times. New Delhi. 31 October 2018. OCLC 61311680. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Noorani, A.G. (2 July 2017). "Save the integrity of the civil service". Deccan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ Naidu, M Venkaiah (31 October 2017). "The great unifier". The Indian Express. OCLC 70274541. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "One Who Forged India's Steel Frame". H.N. Bali. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Jivanta Schoettli (2011). Vision and Strategy in Indian Politics: Jawaharlal Nehru's Policy Choices and the Designing of Political Institutions. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-136-62787-3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 459.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 467.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 467–469.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 472–473.

- ^ a b Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 469–470.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 508–512.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 523–524.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 504–506.

- ^ Patel, Vallabhbhai (1975). Sardar Patel, in Tune with the Millions. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Smarak Bhavan. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Nandurkar, G M (1965). "This Was Sardar The Commemorative Volume Vol 3". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Jha, Dhirendra K. (1 January 2020). "Historical records expose the lie that Nathuram Godse left the RSS". The Caravan. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Gerald James Larson (1995). India's Agony Over Religion. State University of New York Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-7914-2412-X.

- ^ Singh 2015, p. 82.

- ^ Panicker, P L John. Gandhian approach to communalism in contemporary India (PDF). p. 100. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ Jaffrelot 1996, pp. 88, 89.

- ^ Graham 2007, p. 14.

- ^ a b Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed Noorani (2000). The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour. LeftWord Books. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-81-87496-13-7. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Jaffrelot 1996, p. 89.

- ^ Curran, Jean A. (17 May 1950). "The RSS: Militant Hinduism". Far Eastern Survey. 19 (10): 93–98. doi:10.2307/3023941. JSTOR 3023941.

- ^ a b c "Officials Mourn Sardar's Death – Pledge of Service to the Land – Secretary-General's Tribute to the Departed Statesman" (PDF). Press Information Bureau, Government of India – Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017.

- ^ Syed 2010, p. 25.

- ^ "Sardar Vallabhbhai". Time. January 1947. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007.

- ^ a b "RIAF Plane Mishap Near Jaipur" (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive. 16 April 1949. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Press Communique" (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive. 30 June 1949. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, pp. 494–495.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 530.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 532.

- ^ a b Pran Nath Chopra, Vallabhbhai Patel (1999). The collected works of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Volume 15. Konark Publishers. pp. 195, 290. ISBN 978-8122001785.

- ^ "Gazette of India – Extraordinary – Minister of Home Affairs (Resolution)" (PDF). Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Panjabi 1969, pp. 157–158.

- ^ "World-Wide Homage to Sardar Patel – Condolence Messages" (PDF). Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017.

- ^ "State Mourning for Sardar Patel's Death" (PDF). Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017.

- ^ Vallabhbhai Patel, Manibahen Patel (1974). This was Sardar: the commemorative volume Volume 1 of Birth-centenary. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Smarak Bhavan. p. 38.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi 1990, p. 533.

- ^ Padmavathi, S.; Hariprasath, D.G. Hari (2017). Mahatma Gandhi Assassination: J.L. Kapur Commission Report – Part 2 (1st ed.). Notion Press, Inc.

- ^ Blueprint to Bluewater, the Indian Navy, 1951–65, Satyindra Singh, Lancer Publisher

- ^ Rao, Yogita (26 October 2014). "Most schools may skip Ekta Diwas for Diwali break". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ "A Measure of the Man". 5 February 2022. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ "Rupani lauds armed forces for POK strikes", The Times of India, 1 October 2016, archived from the original on 19 October 2017, retrieved 31 October 2016