Ram Prasad Bismil

Ram Prasad Bismil | |

|---|---|

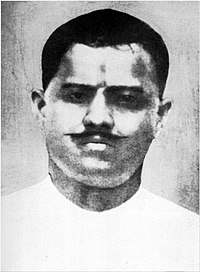

Bismil in 1924 | |

| Born | 11 June 1897 |

| Died | 19 December 1927 (aged 30) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Nationality | British Indian |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations | |

| Organization | Hindustan Republican Association |

| Criminal charges | Robbery |

| Criminal status | Executed |

Ram Prasad Bismil (ⓘ; 11 June 1897 – 19 December 1927) was an Indian poet, writer, and revolutionary who fought against British Raj, participating in the Mainpuri Conspiracy of 1918, and the Kakori Conspiracy of 1925. He composed in Urdu and Hindi under pen names Ram, Agyat and Bismil, becoming widely known under the latter. He was also a translator.

Bismil was associated with Arya Samaj and was one of the founding members of the revolutionary organization Hindustan Republican Association.

He was hanged on 19 December 1927 for his revolutionary activities.

Early life

Ram Prasad Bismil was born on 11 June 1897 to Muralidhar and Moolmati devi in Shahjahanpur district in erstwhile North-Western Provinces. He was born in a Tomar Rajput family.[1][2][3] Pandit was an honorific title conferred to him due to his specialised knowledge on several subjects. He learned Hindi from his father at home and was sent to learn Urdu from a moulvi. He was admitted to an English-language school, despite his father's disapproval, and also joined the Arya Samaj in Shahjahanpur. Bismil showed a talent for writing patriotic poetry.[4] He was inspired by a book written by the great seer Swami Dayananda Saraswati, entitled the Satyarth Prakash.[5]

Contact with Somdev

As an 18-year-old student, Bismil read of the death sentence passed on Bhai Parmanand, a scholar and companion of Har Dayal. At that time he was regularly attending the Arya Samaj Temple at Shahjahanpur daily, where Swami Somdev, a friend of Paramanand, was staying.[6] Angered by the sentence, Bismil composed a poem in Hindi titled Mera Janm (en: My Birth), which he showed to Somdev. This poem demonstrated a commitment to remove the British control over India.[7]

Lucknow Congress

Bismil left school in the following year and travelled to Lucknow with few friends. The Naram Dal ("moderate faction" of the Indian National Congress) was not prepared to allow the Garam Dal to stage a grand welcome of Tilak in the city. They organised a group of youths and decided to publish a book in Hindi on the history of American independence, America Ki Swatantrata Ka Itihas, with the consent of Somdev. This book was published under the authorship of the fictitious Babu Harivans Sahai and its publisher's name was given as Somdev Siddhgopal Shukla. As soon as the book was published, the government of Uttar Pradesh proscribed its circulation within the state.[8]

Mainpuri conspiracy

Bismil formed a revolutionary organisation called Matrivedi (Altar of Motherland) and contacted Genda Lal Dixit, a school teacher at Auraiya. Somdev arranged this, knowing that Bismil could be more effective in his mission if he had experienced people to support him. Dixit had contacts with some powerful dacoits of the state. Dixit wanted to utilise their power in the armed struggle against the British rulers. Like Bismil, Dixit had also formed an armed organisation of youths called Shivaji Samiti (named after Shivaji Maharaj). The pair organised youths from the Etawah, Mainpuri, Agra and Shahjahanpur districts of United Province (now Uttar Pradesh) to strengthen their organisations.[9]

On 28 January 1918, Bismil published a pamphlet titled Deshvasiyon Ke Nam Sandesh (A Message to Countrymen), which he distributed along with his poem Mainpuri Ki Pratigya (Vow of Mainpuri). To collect funds for the party looting was undertaken on three occasions in 1918. Police searched for them in and around Mainpuri while they were selling books proscribed by the U.P. Government in the Delhi Congress of 1918. When police found them, Bismil absconded with the books unsold. When he was planning another looting between Delhi and Agra, a police team arrived and firing started from both the sides. Bismil jumped into the Yamuna and swam underwater. The police and his companions thought that he had died in the encounter. Dixit was arrested along with his other companions and was kept in Agra fort. From here, he fled to Delhi and lived in hiding. A criminal case was filed against them. The incident is known as the "Mainpuri Conspiracy". On 1 November 1919 the Judiciary Magistrate of Mainpuri B. S. Chris announced the judgement against all accused and declared Dixit and Bismil as absconders.[10]

Underground activities by Bismil

From 1919 to 1920 Bismil remained inconspicuous, moving around various villages in Uttar Pradesh and producing several books. Among these was a collection of poems written by him and others, entitled Man Ki Lahar, while he also translated two works from Bengali (Bolshevikon Ki Kartoot and Yogik Sadhan) and fabricated Catherine or Swadhinta Ki Devi from an English text. He got all these books published through his own resources under Sushilmala – a series of publications except one Yogik Sadhan which was given to a publisher who absconded and could not be traced. These books have since been found. Another of Bismil's books, Kranti Geetanjali, was published in 1929 after his death and was proscribed by British Raj in 1931.[11]

Formation of Hindustan Republican Association

In February 1920, when all the prisoners in the Manipuri conspiracy case were freed, Bismil returned home to Shahjahanpur, where he agreed with the official authorities that he would not participate in revolutionary activities. This statement of Ram Prasad was also recorded in vernacular before the court.[12]

In 1921, Bismil was among the many people from Shahjahanpur who attended the Ahmedabad Congress. He had a seat on the dias, along with the senior congressman Prem Krishna Khanna, and the revolutionary Ashfaqulla Khan. Bismil played an active role in the Congress with Maulana Hasrat Mohani and got the most debated proposal of Poorna Swaraj passed in the General Body meeting of Congress. Mohandas K. Gandhi, who was not in the favour of this proposal became quite helpless before the overwhelming demand of youths. He returned to Shahjahanpur and mobilised the youths of United Province for non-co-operation with the Government. The people of U.P. were so much influenced by the furious speeches and verses of Bismil that they became hostile against British Raj. As per statement of Banarsi Lal (approver)[13] made in the court – "Ram Prasad used to say that independence would not be achieved by means of non-violence."[14][failed verification]

In February 1922 some agitating farmers were killed in Chauri Chaura by the police. The police station of Chauri Chaura was attacked by the people and 22 policemen were burnt alive. Gandhi declared an immediate stop to the non-co-operation movement without consulting any executive committee member of the Congress. Bismil and his group of youths strongly opposed Gandhi in the Gaya session of Indian National Congress (1922). When Gandhi refused to rescind his decision, its then-president Chittranjan Das resigned. In January 1923, the rich group of party formed a new Swaraj Party under the joint leadership of Moti Lal Nehru and Chittranjan Das, and the youth group formed a revolutionary party under the leadership of Bismil.[15][16]

Yellow Paper constitution

With the consent of Lala Har Dayal, Bismil went to Allahabad where he drafted the constitution of the party in 1923 with the help of Sachindra Nath Sanyal and another revolutionary of Bengal, Dr. Jadugopal Mukherjee. The basic name and aims of the organisation were typed on a Yellow Paper[17] and later on a subsequent Constitutional Committee Meeting was conducted on 3 October 1924 at Cawnpore in U.P. under the Chairmanship of Sachindra Nath Sanyal.[18]

This meeting decided the name of the party would be the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA). After a long discussion from others Bismil was declared there the District Organiser of Shahjahanpur and Chief of Arms Division. An additional responsibility of Provincial Organiser of United Province (Agra and Oudh) was also entrusted to him. Sachindra Nath Sanyal, was unanimously nominated as National Organiser and another senior member Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee, was given the responsibility of Coordinator, Anushilan Samiti. After attending the meeting in Kanpur, both Sanyal and Chatterjee left the U.P. and proceeded to Bengal for further extension of the organisation.[19]

Manifesto of H.R.A.

A pamphlet entitled as The Revolutionary was distributed throughout the United Province in India in the beginning of January 1925. Copies of this leaflet, referred to in the evidence as the "White Leaflet", were also found with some other alleged conspirators of Kakori Conspiracy as per judgement of the Chief Court of Oudh. A typed copy of this manifesto was found with Manmath Nath Gupta.[17] It was nothing but the Manifesto of H.R.A. in the form of a four paged printed pamphlet on white paper which was circulated secretly by post and by hands in most of the districts of United Province and other parts of India.

This pamphlet bore no name of the printing press. The heading of the pamphlet was: "The Revolutionary" (An Organ of the Revolutionary Party of India). It was given first number and first issue of the publication. The date of its publication was given as 1 January 1925.[20]

Kakori train robbery

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Bismil executed a meticulous plan for looting the government treasury carried in a train at Kakori near Lucknow. This event happened on 9 August 1925 and is known as the Kakori train robbery. Ten revolutionaries stopped the Saharanpur–Lucknow passenger train at Kakori – a station just before Lucknow Junction. German-made Mauser C96 semi-automatic pistols were used in this action. Ashfaqulla Khan, the lieutenant of the HRA Chief Ram Prasad Bismil gave away his Mauser to Manmath Nath Gupta and engaged himself to break open the cash chest. Eagerly watching a new weapon in his hand, Manmath Nath Gupta fired the pistol and accidentally shot and killed passenger Ahmed Ali, who had gotten down from the train to see his wife in the ladies compartment.

More than 40 revolutionaries were arrested whereas only 10 persons had taken part in the decoity. Persons completely unrelated to the incident were also captured. However some of them were let off. The government appointed Jagat Narain Mulla as public prosecutor at an incredible fee. Dr. Harkaran Nath Mishra (Barrister M.L.A.) and Dr. Mohan Lal Saxena (M.L.C.) were appointed as defence counsel. A defence committee was also formed to defend the accused.[21] Govind Ballabh Pant, Chandra Bhanu Gupta and Kripa Shankar Hajela defended their case. The men were found guilty and subsequent appeals failed. On 16 September 1927, a final appeal for clemency was forwarded to the privy council in London but that also failed.[22]

Following 18 months of legal process, Bismil, Ashfaqulla Khan, Roshan Singh and Rajendra Nath Lahiri were sentenced to death. Bismil was hanged on 19 December 1927 at Gorakhpur Jail, Ashfaqulla Khan at the Faizabad Jail and Thakur Roshan Singh at Naini Allahabad Jail. Lahiri had been hanged two days earlier at Gonda Jail.

Bismil's body was taken to the Rapti river for a Hindu cremation, and the site became known as Rajghat.[23]

Literary works

Bismil published a pamphlet titled Deshvasiyon ke nam sandesh (en: A message to my countrymen). While living underground, he translated some of Bengali books viz. Bolshevikon Ki Kartoot (en: The Bolshevik's programme) and Yogik Sadhan (of Arvind Ghosh). Beside these a collection of poems Man Ki Lahar (en: A sally of mind) and Swadeshi Rang was also written by him. Another Swadhinta ki devi: Catherine was fabricated from an English book[24] into Hindi. All of these were published by him in Sushil Mala series. Bismil wrote his autobiography while he was kept as condemned prisoner in Gorakhpur jail.[25][26]

The autobiography of Ram Prasad Bismil was published under the cover title of Kakori ke shaheed by Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi in 1928 from Pratap Press, Cawnpore. A rough translation of this book was prepared by the Criminal Investigation Department of United Province in British India. Translated book was circulated as confidential document for official and police use throughout the country.[27]

He immortalised the poem Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna, Man Ki Lahar and Swadeshi Rang as a war cry during the British Raj period in India.[28] It was first published in journal "Sabah", published from Delhi.[29]

Memorials

Shaheed Smarak Samiti of Shahjahanpur established a memorial at Khirni Bagh mohalla of Shahjahanpur city where Bismil was born in 1897 and named it "Amar Shaheed Ram Prasad Bismil Smarak". A statue made of white marble was inaugurated by the then Governor of Uttar Pradesh Motilal Vora on 18 December 1994 on the eve of the martyr's 69th death anniversary.[30]

The Northern railway zone of Indian Railways built the Pt Ram Prasad Bismil railway station, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from Shahajahanpur.[31]

There is a memorial to the Kakori conspiracists at Kakori itself. It was inaugurated by the prime minister of India, Indira Gandhi, on 19 December 1983.[32]

The Government of India issued a multicoloured commemorative postal stamp on 19 December 1997 in Bismil's birth centenary year.[33]

The government of Uttar Pradesh had named a park after him: Amar Shaheed Pt. Ram Prasad Bismil Udyan is near Rampur Jagir village, where Bismil lived underground after the Mainpuri conspiracy case in 1919.[34]

See also

References

- ^ Manoj Dole. Great Indian Freedom Fighter. p. 74.

- ^ Rana, Pushpendra (12 June 2023). "Remembering Shaheed Ram Prasad 'Bismil' Tomar". Times of India.

- ^ Sengupta, Arjun (12 June 2023). "A revolutionary and a poet: Who was Ram Prasad Bismil?". The Indian Express.

- ^ "Ramprasad. Bismil's Idea of Revolution Is Impervious to Saffronisation". thewire.in. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Nair, Rukmini Bhaya; deSouza, Peter Ronald (20 February 2020). Keywords for India: A Conceptual Lexicon for the 21st Century. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-03925-4.

- ^ Waraich 2007, p. 32.

- ^ "Who is Ram Prasad Bismil, the young freedom fighter who inspired a generation". The Indian Express. 11 June 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Lucknow Congress". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Bismil 1927, p. 27.

- ^ "Revolutionary actions in Mainpuri". Sankalp Foundation.

- ^ "Ramprasad Bismil's Idea of Revolution Is Impervious to Saffronisation". The Wire. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "Hindustan Republic Association". IAS toppers.

- ^ Manzar, Habib (2004). "Revisiting Kakori Case on the basis of Vernacular Reportage". In Sinha, Atul Kumar (ed.). Perspectives in Indian History. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 180. ISBN 9788179750766.

- ^ Singh, Bhagat (2007). "Review Article" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Arya 1984.

- ^ Waraich 2007, p. 56.

- ^ a b Manzar, Habib (2004). "Revisiting Kakori Case on the basis of Vernacular Reportage". In Sinha, Atul Kumar (ed.). Perspectives in Indian History. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 178. ISBN 9788179750766.

- ^ Bhishma 1929, p. 71.

- ^ Simha 2009, p. v. 11.

- ^ Waraich, Malwinder Jit Singh (2007). Hanging of Ram Prasad Bismil: the judgement. Unistar Books, Chandigarh. pp. 12–13. OCLC 219562122.

- ^ Manzar, Habib (2004). "Revisiting Kakori Case on the basis of Vernacular Reportage". In Sinha, Atul Kumar (ed.). Perspectives in Indian History. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9788179750766.

- ^ Waraich 2007, p. 97.

- ^ "VIDEO: देश में बना पहला अशफाक उल्ला खां और राम प्रसाद बिस्मिल स्मारक, हिंदू-मुस्लिम भाईचारे की मिसाल कर रहा पेश". Patrika News (in Hindi). 23 January 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Breshko-Breshkovskaia, Ekaterina Konstantinovna; Blackwell, Alice Stone (1 January 1918). "The little grandmother of the Russian revolution;". Boston, Little, Brown – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Rajesh Tanti (24 June 2016). Hindi Ramprasad Bismil Ki Atmakatha.

- ^ Arya 1984, p. 93.

- ^ Bhishma 1929, p. 125.

- ^ Hasan, Mushirul (2016). Roads to Freedom: Prisoners in Colonial India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199089673. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ Ulhaque, T. M. Zeya (November 2013). "Bismil Azimabadi : Life Sketch". Spritualworld.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "जयंती विशेष:रामप्रसाद बिस्मिल ने फांसी से तीन दिन पहले इस जेल में पूरी की थी आत्मकथा". Amar Ujala (in Hindi). Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "PRPM/Pt Ram Prasad Bismil (1 PFs) Railway Station Map/Atlas – India Rail Info".

- ^ Sinha, Arunav (9 August 2011). "Tourist spot tag may uplift Kakori". The Times of India. Lucknow. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "RAM PRASAD BISMIL – ASHFAQUALLAH KHAN".

- ^ "वतन की ख्वाहिशों पे जिंदगानी कुर्बान(en:Sacrifice of life for homeland)". Dainik Jagran (Hindi Jagran City-Greater Noida) New Delhi. 12 August 2012. p. 24.

Further reading

- Simha, Ema Ke (2009). Encyclopaedia of Indian war of independence, 1857–1947. Vol. v.11. Anmol Publications, New Delhi, India. OCLC 277548369.

- Bhishma, (pseud) (1929). Kakori-ke-shahid: martyrs of the Kakori conspiracy case. Government Press, United Provinces, Allahabad. p. 125. OCLC 863324363.

- Bismil, Ram Prasad (1927). Main Krantikari kaise bana. 44 Books. ISBN 9788128808166.

- Arya, Amit (1984). राम प्रसाद बिस्मिल जी की जीवनी हिंदी की सर्वश्रेष्ठ आत्मकथा. New Delhi, India: Amitaryavart. ISBN 978-81-7871-059-4.

- Waraich, Malwinder Jit Singh (2007). Misusing from the gallows: autobiography of Ram Prasad Bismil. Ludhiana: Unistar books. p. 101. OCLC 180690320.

External links

- Hindi-language poets

- Hindi-language writers

- Urdu-language poets from India

- Indian male poets

- 1897 births

- 1927 deaths

- Revolutionary movement for Indian independence

- People from Shahjahanpur

- People from Gorakhpur

- 20th-century executions by British India

- Hindustan Socialist Republican Association

- Executed Indian revolutionaries

- People executed by British India by hanging

- 20th-century Indian poets

- Poets from Manipur