Ibn Furak

Ibn Fūrāk ابن فورك | |

|---|---|

| Title | Al-Ḥāfiẓ |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 941 |

| Died | 1015 (aged 73–74) |

| Cause of death | assassinated |

| Resting place | al-Hira |

| Era | Islamic golden age |

| Region | Khorasan |

| Main interest(s) | Theology (Kalam), Logic, Islamic Jurisprudence, Hadith, Arabic grammar |

| Notable work(s) | Mujarrad Maqalat al-Shaykh Abi al-Hasan al-Ash'ari ("Summary of Shaykh Abi al-Hasan al-Ash'ari's Treatises/Articles"), Mushkil al-Hadith wa Bayanuh ("Ambiguity of the Hadith and its Explanation") |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Shafi'i[1] |

| Creed | Ash'ari[2][3][4] |

| Muslim leader | |

Influenced | |

| Part of a series on |

| Ash'arism |

|---|

|

| Background |

Muhammad ibn al-Hasan ibn Fūrāk, Abū Bakr al-Asbahānī al-Shāfi`ī, commonly known as Ibn Fūrāk (Arabic: ابن فورك); c. 941–c. 1015 CE / 330–406 AH). The Imam, a leading authority on kalam and usul, the transmitter of Al-Ash`ari's school, an expert in Arabic language, grammar and poetry, an orator, a jurist, and a hadith master from the Shafi'i Madhhab in 10th century.[5]

Life

[edit]Birth and Education

[edit]Ibn Furak was born in around 941 CE (330 AH) in Isfahan. He studied the Ash'ari theology under Abu al-Hasan al-Bahili along with Al-Baqillani and Abu Ishaq al-Isfarayini in Basra and Baghdad, and also Prophetic traditions under 'Abd Allah bin Ja'far al-Isbahani. From 'Iraq he went to Rayy, then to Nishapur, where a madrasa was built for him beside the Khanqah of the Sufi al-Bushandji. He was in Nishapur before the death of the Sufi Abu 'Uthman al-Maghribi in 373/983, and the saint would instruct Ibn Furak to lead the burial prayer over him prior to his death.[6][5][7]

Scholarly career

[edit]Ibn Furak was the teacher and master of al-Qushayri and al-Bayhaqi who both would frequently cite in their popular works Al-Risala and Al-Asma' wa al-Sifat, respectively. He debated and won against the anthropomorphist Karramiyya in Rayy, then he travelled to Nishapur where he trained and taught the next generation of jurists at a school established in his honour, which was an extension of the previous Sufi school (Khanqah) built by Abû al-Hasan al-Bushanji. In Nishapur, he brought the transmissions of the narrators of Basra and Baghdad, both from Iraq, and also authored a number of books in various fields and Islamic sciences.[5][8]

Dispute and Death

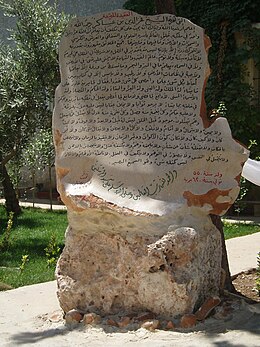

[edit]The Karramiyya tried to initially have him executed by the Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni but failed after the Sultan summoned him to Ghazni and questioned him then exonerated him of the erroneous charges they had brought against him as Ibn Furak was found innocent from the false accusations laid out by his enemies. However, upon returning from Ghazni, he was poisoned by the angered Karramiyya, fell on the road, and died in 1015 CE (406 AH) while another version says that he was attacked from behind from them. He was carried back to Nishapur and buried in al-Hira. According to Ibn Asakir, the grave of Ibn Furak is a place where people go to seek healing (istishfâ') and have their prayers granted.[8]

Controversy over Ibn Furak

[edit]Al-Dhahabi mentions Ibn Furak in a short reference stating some inaccurate and defaming reports from Ibn Hazm, without questioning their intent where Ibn Furak was unjustly accused of claiming the prophethood ends after the death of Muhammad and other slanders that accuse him of disbelief. Despite this, Al-Dhahabi goes on to say: "Ibn Furak was better than Ibn Hazm, of a greater stature (rank among scholars) and better belief (creed)."[9]

Ibn al-Subki provided evidence that this statement by Ibn Hazm were "anti-Ash'ari fabrications and forgeries" falsely attributed to Ibn Furak. He showed how these reports were refuted by Al-Qushayri and Ibn al-Salah. Ibn al-Subki then quotes Ibn Furak's own words testifying his true creed. Ibn Furak says:[9]

“The Ash'ari belief (creed) is that our prophet (ﷺ) is alive in his Blessed Grave and is the Messenger of Allah (God), forever until the End of times, this is literally, not metaphorically or symbolically, and the correct Belief is that he (Prophet Muhammad ﷺ) was a Prophet when Adam (ﷺ) was between Water and Clay, and his Prophethood remains until now, and shall ever remain.”

Character

[edit]According to the martyred Imam Abu al-Hajjaj Yusuf ibn Dunas al-Findalawi al-Maliki, Ibn Furak would always sleep elsewhere out of reverence for a house that cantained a volume of the Qur'an.[10]

Works

[edit]Ibn Furak's works in "Usul al-Din" (foundation of religion), "Usul al-fiqh" (foundation of jurisprudence), and the meanings of the Quran count nearly one hundred volumes. Among them are Mujarrad Maqalat al-Ash'ari and Kitab Mushkil al-hadith wa-bayanihi (with many variants of the title), in which he refuted both the anthropomorphist tendencies of karramis and the over-interpretation of the Mu'tazila. Ibn Furak said that he embarked on the study of kalam because of the hadîth reported from the Prophet.[11]

His main work in the eyes of later generations is Tabaqat al-mutakallimin which is the main source to study al-Ash'ari theology.[7]

Early Islam scholars

[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Lewis, B.; Menage, V.L.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (1986) [1st. pub. 1971]. Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. III (H-Iram) (New ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 767. ISBN 9004081186.

- ^ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2009). Hadith: Muhammad's Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World (Foundations of Islam). Oneworld Publications. p. 154. ISBN 978-1851686636.

- ^ a b Lewis, B.; Menage, V.L.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (1986) [1st. pub. 1971]. Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. III (H-Iram) (New ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 766. ISBN 9004081186.

- ^ Adang, Camilla; Fierro, Maribel; Schmidtke, Sabine (2012). Ibn Hazm of Cordoba: The Life and Works of a Controversial Thinker (Handbook of Oriental Studies) (Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 1; The Near and Middle East). Vol. I (A-B). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 384. ISBN 978-90-04-23424-6.

- ^ a b c Al-Bayhaqi 1999, p. 26

- ^ Gibril Fouad Haddad 2015, p. 155

- ^ a b "Furak". Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Al-Bayhaqi 1999, p. 27

- ^ a b Gibril Fouad Haddad 2015, p. 155-156

- ^ Al-Bayhaqi 1999, p. 28

- ^ Brown, Jonathan (2007). The Canonization of Al-Bukhari and Muslim: The Formation and Function of the Sunni Hadith Canon (reprint ed.). BRILL. p. 190. ISBN 978-9-004158399.

Bibliography

[edit]- R. Y., Ebied & Van Renterghem, Vanessa (1960–2005). "Ibn Fūrak". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition (12 vols.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_032.

- Al-Bayhaqi (1999). Allah's Names and Attributes. Vol. 4 of Islamic Doctrines & Beliefs. Translated by Gibril Fouad Haddad. Islamic Supreme Council of America. p. 26-28. ISBN 9781930409033.

- Gibril Fouad Haddad (2 May 2015). "Ibn Furak (330 AH – 406 AH, 73-74 years old)". The Biographies of the Elite Lives of the Scholars, Imams & Hadith Masters. As-Sunnah Foundation of America. pp. 155–158.

- 940s births

- 1015 deaths

- Shafi'is

- Asharis

- Sunni imams

- 10th-century Iranian writers

- 10th-century Muslim theologians

- Hadith scholars

- 10th-century linguists

- Quranic exegesis scholars

- Medieval grammarians of Arabic

- Sunni Muslim scholars of Islam

- 10th-century Muslim scholars of Islam

- 10th-century jurists

- 11th-century jurists

- 11th-century Iranian writers