Lesbian erotica

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Lesbian erotica deals with depictions in the visual arts of lesbianism, which is the expression of female-on-female sexuality. Lesbianism has been a theme in erotic art since at least the time of ancient Rome, and many regard depictions of lesbianism (as for sexuality in general) to be erotic.

For much of the history of cinema and television, lesbianism was considered taboo, though since the 1960s it has increasingly become a genre in its own right. First found in softcore movies and erotic thrillers, depictions of lesbianism entered mainstream cinema in the 1980s. In pornography, depictions of lesbian sex form a popular subgenre, often directed toward male heterosexual audiences. They are also increasingly developed for lesbian audiences, and bisexual audiences of any gender.

Cultural background

[edit]Sexual relations between women have been illustrated as well as narrated, but much of the written material from the early modern period has been destroyed.[1] What seems clear from the historical record is that much of the lesbian material in pornographic texts was intended for a male readership.[2]

Visual arts

[edit]Classic and classical depictions

[edit]

An Attic red figure vase in the collection of the Tarquinia National Museum in Italy shows a kneeling woman touching the genitals of another woman, a rare explicit portrayal of sexual activity between women in Greek art,[3] although it has also been interpreted as depicting one prostitute shaving or otherwise grooming the other in a non-sexual fashion.[4] Depictions of lesbianism are found among the erotic frescoes of Pompeii.[citation needed]

Having all but disappeared during the Middle Ages, they made a comeback after the Renaissance. François Boucher and J. M. W. Turner were among the forerunners of 19th century artists who featured eroticism between women among their work. Like other painters (such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard), Boucher found inspiration in classical mythology. He was one of many artists to use various myths surrounding the goddess Diana, including the often-depicted story of Callisto, Diana's nymph who was seduced by Jupiter, with the god taking Diana's form since Callisto had vowed chastity.[5]

19th-century developments

[edit]In the 19th century, lesbianism became more openly discussed and found its way into many fields of art. In France, the influence of Charles Baudelaire is considered crucial, on literature as well as on the visual arts,[6] though according to Dorothy Kosinski it was a matter not for the high arts but mostly for popular erotica.[5] Auguste Rodin's illustrations for Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal included lesbian scenes.[6] Gustave Courbet's Le Sommeil (1866) illustrates a scene from the 1835 story "Mademoiselle de Maupin" by Théophile Gautier (though Baudelaire's "Delphine et Hippolyte" from Les fleurs is also cited as an inspiration),[6] depicting two women asleep after love-making.[7][8] Its lesbian subject matter was controversial enough to be the subject of a police report in 1872,[9] but Courbet's painting is credited with inspiring others to depict "sapphic couple[s]", which in turn led to "soften[ing] taboos by revealing love between women and forcing society to see those whom it regarded as deviants and sinners."[10] Nonetheless, the audience for such artwork was predominantly male (Courbet's painting was commissioned by a profligate Turkish diplomat), therefore "the term lesbian should perhaps be provided with quotation marks, insofar as we are dealing with images made by men, for men, and in which the very disposition of the women's bodies declares that they are arranged more for the eyes of the viewer than for those of one another."[11] In the twentieth century the image's sensuality would appeal to lesbian viewers as well.[12]

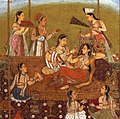

In 19th century French painting, lesbianism was often depicted within the context of orientalism, and was thus apt to be affected by the era's colonialism and imperialism; as a result, assumptions regarding race and class informed the images, especially when lesbianism was linked to harem and brothel scenes. Later depictions of lesbians in Western art may reflect like cultural mores, or merely borrow from formal pictorial conventions.[13]

In the second half of the 19th century, the lesbian theme was well-established, and its artists include Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec,[5] Constantin Guys,[5] Edgar Degas,[5] and Jean-Louis Forain.[5] Later artists include Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Christian Schad,[14] Albert Marquet, Balthus, and Leonor Fini. More explicit depictions were an important part of the work of erotic illustrators such as Édouard-Henri Avril, Franz von Bayros, Martin van Maële, Rojan, Gerda Wegener, and Tom Poulton. Explicit depictions of lovemaking between women were also an important theme in Japanese erotic shunga, including the work of such masters as Utamaro, Hokusai, Katsukawa Shunchō, Utagawa Kunisada, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Yanagawa Shigenobu, Keisai Eisen, and Kawanabe Kyōsai.

In art photography and fetish photography, notable artists to work with lesbian themes include David Hamilton, Steve Diet Goedde and Bob Carlos Clarke. More recently, lesbian and bisexual photographers such as Nan Goldin, Tee Corinne, and Judy Francesconi have focused on erotic themes, reclaiming a subject that has traditionally been mainly treated through the eye of male artists.

Cinema and television

[edit]Lesbian and erotic themes were restrained or coded in early cinema. Even scenes suggestive of lesbianism were controversial, such as the presentation of women dancing together in Pandora's Box (1929) and The Sign of the Cross (1932). Pandora's Box is notable for its lesbian subplot with the Countess (Alice Roberts) being defined by her masculine look and because she wears a tuxedo. Lesbian themes were found in European films such as Mädchen in Uniform (1931). By the mid-1930s, the Hays Code banned any homosexual themes in Hollywood-made films and several pre-Code films had to be cut to be re-released. For example, The Sign of the Cross originally included the erotic "Dance of the Naked Moon",[15] but the dance was considered a "lesbian dance" and was cut for a 1938 reissue. Even suggestions of a romantic attraction between women were rare, and the "L-word" was taboo. Lesbianism was not treated in American cinema until the 1962 release of Walk on the Wild Side in which there is a subtly implied lesbian relationship between Jo and Hallie. Depictions of lovemaking between women first appeared in several films of the late 1960s – The Fox (1967), The Killing of Sister George (1968), and Therese and Isabelle (1968).

During the 1970s, depictions of sex between women were largely restricted to semi-pornographic softcore and sexploitation films, such as Cherry, Harry & Raquel! (1970), Score (1974), Emmanuelle (1974), Bilitis (1977) and Caligula (1979). Although semi-explicit heterosexual sex scenes had been part of mainstream cinema since the late 1960s, equivalent depictions of women having sex only began making their appearance in mainstream film during the 1980s. These were typically in the context of a film that was specifically lesbian-themed, such as Personal Best (1982), Lianna (1983), and Desert Hearts (1985). The vampire film The Hunger (1983) also contained a seduction and sex scene between Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon. Jacques Saurel's film "Joy et Joan" (1985) also belongs to this new more-than-softcore film performance.

Henry & June (1990) had several lesbian scenes, including one that was considered explicit enough to give the film an NC-17 rating. (There was some controversy as to whether the MPAA had given the film a more restrictive rating than it normally would have because of the lesbian nature of the scene in question.) Basic Instinct (1992) contained mild lesbian content, but established lesbianism as a theme in the erotic thriller genre. Later, in the 1990s, erotic thrillers such as Showgirls, Wild Side (1995), Crash (1996) and Bound (1996) explored lesbian relationships and contained explicit lesbian sex scenes.[16]

From the 1990s, depictions of sex between women became fairly common in mainstream cinema. Females kissing has increasingly been shown in films and on television, often as a way to include a sexually arousing element in a film without actually having the film gain a more restrictive rating by depicting sex or nudity.[citation needed]

The Showtime drama series The L Word (2004–2009) explores lesbian, bisexual, and transgender relationships, and contains numerous explicit lesbian sex scenes.

Pornography

[edit]

Lesbianism is an important theme in both hardcore and softcore pornography, with many adult video titles, websites, and entire studios (such as Girlfriends Films and Sweetheart Video) devoted entirely to depictions of sexual activity between women.[17] Lesbian pornography typically is aimed predominantly at a male audience, with a smaller female audience, and many heterosexual adult videos include a lesbian sex scene. However, in Japanese adult video, lesbianism is considered a fetish and is only occasionally included in heterosexual videos. Rezu (レズ—lesbian) video is a specialized genre, though a large number of such videos are produced.[18]

Audience

[edit]Erotica and pornography involving sex between women have been predominantly produced by men for a male and female audience. A 1996 study by Henry E. Adams, Lester W. Wright Jr., and Bethany A. Lohr, published in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, found that heterosexual men have the highest genital and subjective arousal to pornography depicting heterosexual activity, rather than lesbian activity.[19] Another study by J. Michael Bailey indicated that heterosexual men are more aroused by depictions involving lesbian sex than they are by depictions of heterosexual activity, while heterosexual and lesbian women were aroused by a wide range of sexual stimuli.[20] On-screen lesbian sex (in both Western and Japanese pornography), while typically aimed at a male audience, has developed a small lesbian audience as well, but still contrasts with gay male pornography, which is considered a genre of its own.

Deborah Swedberg, in an analysis published in the NWSA Journal in 1989, argues that it is possible for lesbian viewers to reappropriate lesbian porn. Swedberg notes that, typically, all-women films differ from mixed porn (with men and women) in, among other things, the settings (less anonymous and more intimate) and the very acts performed (more realistic and emotionally involved, and with a focus on the whole body rather than just the genitals): "the subject of the heterosexually produced all-women videos is female pleasure". She argues (against Laura Mulvey's "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cineman" and Susanne Kappeler's Pornography and Representation, for example) that such movies allow for female subjectivity since the women are more than just objects of exchange.[21] Appropriation by women of male-made lesbian erotica (such as by David Hamilton) was signaled also by Tee Corinne.[22]

Some pornography is made by lesbians, such as the defunct lesbian erotic magazine On Our Backs; videos by Fatale Media, SIR Video, Pink and White Productions, and BLEU Productions; and web sites such as the CyberDyke Network.

A Pornhub report indicates that "lesbian", "orgy", "BDSM" are the most popular category for female viewers of its porn portal. The category was 151% more popular with women than with men.[23]

Mainstream inauthenticity

[edit]Mainstream lesbian pornography is criticized by some members of the lesbian community for its inauthenticity.[24] According to author Elizabeth Whitney, "lesbianism is not acknowledged as legitimate" in lesbian porn due to the prevalence of "heteronormatively feminine women", the experimental nature, and the constant catering to the male gaze, all of which counter real life lesbianism.[24]

A study conducted by Valerie Webber found that most actors in lesbian porn consider their own pornographic sex somewhere on a spectrum between real and fake sex, depending on several factors.[24] They were more likely to consider it authentic if there was a real attraction between themselves and the other actor(s) in the scene,[24] and if they felt mutual respect between themselves and the producers.[24]

Authenticity in porn is disputed because some assert that the only authentic sex has no motive other than sex itself.[24] Porn sex, being shot for a camera, automatically has other motives than sex itself.[24] On the other side, some assert that all porn sex is authentic since the sex is an occurrence that took place, and that is all that is needed to classify it as authentic.[24]

With regard to the authenticity of their performance, some lesbian porn actors describe their performance as an exaggerated, altered version of their real personality, providing some authenticity to the performance.[24] Authenticity depends on real life experiences, so some lesbian porn actors feel the need to create an entirely different persona to feel safe.[24] Webber writes of Agatha, a queer actor in lesbian porn who "prefers that the activity and ambiance of her performances be very inauthentic, because otherwise it feels 'too close to home'", referring to the oppression and verbal abuse she is subject to by homophobic men in her daily life.[24]

Penetration

[edit]Like in straight and gay male porn, there is an emphasis on penetration in lesbian porn.[24] Even though studies have found that dildos have minimal use in real life lesbian sexual activity,[24][25][26] lesbian porn prominently features dildos.[24] According to Lydon, the ability to achieve orgasm clitorally, as opposed to penetratively, eliminates the need for a phallus and, by extension, for a man.[24] For this reason, male producers continue to include, and male viewers continue to demand, a phallus as a central feature in lesbian porn.[24]

Views on lesbianism in erotica

[edit]

Effects on heterosexual men

[edit]Several penile plethysmography studies have shown high levels of arousal in heterosexual men to pornography showing sexual activity between women.[19][20] One study found heterosexual men to have the highest genital and subjective arousals to pornography depicting heterosexual activity, rather than lesbian activity,[19] while another study reported that on average heterosexual men are more aroused by pornography showing sexual activity between women than they are by depictions of heterosexual activity.[20] These findings correspond with reports in several earlier studies (summarized in Whitley et al. (1999);[27] see also anecdotal reports in Loftus (2002)).[28]

Male perception of lesbianism as erotic has been shown[27] to correspond with recent exposure to lesbian pornography; however, men who have recently viewed lesbian pornography are no more likely than others to perceive lesbians as hypersexual and/or bisexual. Bernard E. Whitley Jr., et al. hypothesized, upon reaching this conclusion, that "pornography may [...] lead heterosexual men to view lesbianism as erotic by means of a generalized association of female-female sexual activity with sexual arousal", but noted that "more research is needed to clarify the relationship between exposure to pornography and the perceived erotic value of lesbianism."

Enjoyment of lesbian pornography can have little connection to feelings towards homosexuals in real life. A heterosexual man may be aroused by pornographic depictions of lesbianism yet hold homophobic views. However, several studies suggest that men who perceive lesbianism as erotic may have less negative attitudes toward lesbians than they do toward gay men.[27][29] Studies have further shown that, while men tend to correlate lesbianism with eroticism more often than women do, women perceive male homosexuality as erotic no more often than men do.[27]

Feminist views

[edit]Lesbian views on sex between women in erotica are complex. Historically, women have been less involved in the production and consumption of erotica in general and visual pornography in particular than have men. Since the late 1960s, radical feminist objections to pornography and the sexual objectification of women have influenced the lesbian community, with some feminists objecting to all pornography. However, since the end of the 1980s' "Feminist Sex Wars" and the beginning of the "women's erotica" movement, feminist views on pornography, both lesbian and heterosexual, have shifted.[30]

Some lesbians are even consumers of mainstream pornography, but many dislike what they perceive as inaccurate and stereotypical depictions of women and lesbianism in mainstream pornography. Some are also uncomfortable with male interest in lesbians.[31] As of the early 2000s, there is a very strong lesbian erotic literature movement, as well as a small genre of pornography made by lesbians for a lesbian audience.

An increasing amount of queer erotic literature has been released in recent decades, written by women and usually for women.[32] There is a large sub-category of this erotica that involves various queer relationships while also including bisexuality and transgender characters into the writing.[32] By introducing various other identities and sexualities, it opens up the erotica world to more gender-fluidity and acceptance of other queer or non-heteronormative sexualities.[32]

Illustrations

[edit]-

Louis Marie de Schryver - Lesbians, 1907

-

Jan Ciągliński - Symbolic dance, 1766 - National Museum in Warsaw

-

Illustration de Maurice Ray pour le roman Aphrodite de Pierre Louÿs en 1931.

-

"Les Deux Amies" par Jean-Jacques Lagrenée (1739-1821).

-

Maxmilian Pirner - potok (1903

-

Alexandre Jacques Chantron - Pleasures of Summer

-

Late 19th-century painting by Édouard-Henri Avril showing the use of a strap-on dildo

-

La lutte des baigneuses - Etienne Dinet

-

J Scalbert - The Bath

-

Virgílio Maurício - L'heure du Gouter, 1914

-

Sappho by Amanda Brewster Sewell, 1891.

-

Dessins de Martin van Maele

-

Amours, galanteries, intrigues, ruses et crimes des capucins et des religieuses, 1788

-

Victory of Faith - Saint George Hare

-

Viola and the Countess - Frederick Richard Pickersgill

-

A historic shunga woodblock printing from Japan depicting two women having sex.

-

Les Liaisons dangereuses, Scène du lit par George Barbier, 1920.

-

Plate XV from "De Figuris Veneris"

-

Nicolas Poussin - L'Empire de Flore

-

清代秘戲圖

-

清代秘戲圖

-

清代秘戲圖

-

"Deux jeunes amies qui s'embrassent" de L.L. Boilly

-

S/M lesbian sexuality

-

Otto Schoff, Siesta

-

Negresco Nymphes playing the flute by François Boucher

-

Les Confidences Pastorales

-

An Orientalist depiction (cunnilingus as exotica)

-

Fanny Hill and Phoebe, circa 1787

-

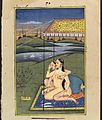

Kama Sutra lesbian

-

Les Délassements d'Eros, 1925

-

A 1925 Gerda Wegener painting of two women engaging in mutual manual stimulation

-

In bed - the kiss by Toulouse Lautrec

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mourão, Manuela (1999). "The Representation of Female Desire in Early Modern Pornographic Texts, 1660–1745". Signs. 24 (3): 573–602. doi:10.1086/495366. JSTOR 3175319. PMID 22315732. S2CID 46259009.

- ^ Faderman, Lillian (1981). Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love between Women from the Renaissance to the Present. New York: William Morrow. pp. 38–46.

- ^ Dover, Kenneth James (1978). Greek Homosexuality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7156-1111-1.

- ^ Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta. "The erotic ceramics of the National Archaeological Museum in Tarquinia". Finestre sull' Arte.

- ^ a b c d e f Kosinski, Dorothy M. (1988). "Gustave Courbet's "The Sleepers": The Lesbian Image in Nineteenth-Century French Art and Literature". Artibus et Historiae. 9 (18): 187–99. doi:10.2307/1483342. JSTOR 1483342.

- ^ a b c Ladenson, Elisabeth (2007). Dirt for Art's Sake: Books on Trial from Madame Bovary to Lolita. Cornell UP. pp. 75–. ISBN 9780801441684. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ Reed, Christopher (2011). Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas. Oxford UP. p. 77. ISBN 9780195399073. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ MacK, Gerstle (1951). Gustave Courbet: A Biography. Da Capo Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780306803758. Retrieved December 11, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Faunce, Sarah; Nochlin, Linda (1988). Courbet reconsidered: exhibition held at the Brooklyn museum, November 4, 1988 – January 16, 1989, Minneapolis institute of arts, February 18 – April 30, 1989. Brooklyn museum, Minneapolis institute of arts. Brooklyn: Brooklyn museum. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-300-04298-6.

- ^ Zimmerman 2000, p. 311.

- ^ Faunce, Sarah; Nochlin, Linda (1988). Courbet reconsidered: exhibition held at the Brooklyn museum, November 4, 1988 – January 16, 1989, Minneapolis institute of arts, February 18 – April 30, 1989. Brooklyn museum, Minneapolis institute of arts. Brooklyn: Brooklyn museum. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-300-04298-6.

- ^ Zimmerman 2000, p. 69.

- ^ Zimmerman 2000, p. 68.

- ^ Saltz, Jerry (May 23, 2003). "Lewd Awakening: Rediscovering a German Connoisseur of Sex". Village Voice. Archived from the original on March 28, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Vieira 1999, pp. 106–109.

- ^ "Sex in Cinema: Brief Historical Overview". www.filmsite.org. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Rutter, Jared (July 2008). "The New Wave of Lesbian Erotica". AVN. pp. 80–88. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ Tetsuwan Atom (2001). "Japanese AV FAQ". Lezlovevideo.com. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c Adams, HE; Wright, LW Jr; Lohr, BA (1996). "Is homophobia associated with homosexual arousal?" (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 105 (3): 440–445. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.440. PMID 8772014.

- ^ a b c Chivers, ML; Rieger, G; Latty, E; Bailey, JM (2004). "A sex difference in the specificity of sexual arousal" (PDF). Psychological Science. 15 (11): 736–744. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00750.x. PMID 15482445. S2CID 5538811. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2006.

- ^ Swedberg, Deborah (1989). "What Do We See When We See Woman/Woman Sex in Pornographic Movies". NWSA Journal. 1 (4): 602–16. JSTOR 4315957.

- ^ Henry, Alice (1983). "Interview [with Tee Corinne]: Images of Lesbian Sexuality". Off Our Backs. 13 (4): 10–12. JSTOR 25774959.

- ^ "Even Straight Women Love to Watch Lesbian Sex-We Asked a Sex Therapist to Explain Why". Health.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Webber, Valerie (2012). "Shades of gay: Performance of girl-on-girl pornography and mobile authenticities". Sexualities. 16 (1–2): 217–235. doi:10.1177/1363460712471119. S2CID 144842110. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ Jerrold S. Greenberg; Clint E. Bruess; Sarah C. Conklin (2010). Exploring the dimensions of human sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 489–490. ISBN 9780763797409. 9780763741488. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Jonathan Zenilman; Mohsen Shahmanesh (2011). Sexually Transmitted Infections: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 329–330. ISBN 978-0495812944. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Whitley, BE Jr; Wiederman, MW; Wryobeck, JM (1999). "Correlates of heterosexual men's eroticization of lesbianism". Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 11: 25–41. doi:10.1300/J056v11n01_02. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009.

- ^ Loftus, David (2020). Watching sex: how men really respond to pornography. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-360-0. Kustritz, Anne (September 2003). "Slashing the Romance Narrative". The Journal of American Culture. 26 (3): 371–384. doi:10.1111/1542-734X.00098.

- ^ Louderback, Laura A.; Whitley, Bernard E. (1997). "Perceived Erotic Value of Homosexuality and Sex-Role Attitudes as Mediators of Sex Differences in Heterosexual College Students' Attitudes toward Lesbians and Gay Men". The Journal of Sex Research. 34 (2): 175–182. doi:10.1080/00224499709551882. ISSN 0022-4499. JSTOR 3813565.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel. "Pornography". In Dynes, Wayne R (ed.). Encyclopedia of Homosexuality (PDF). Archived from the original on October 24, 2021.

A development of the 1980s is the birth of a true women's pornographic movement, in which women create and market erotic materials for female consumption, both homosexual and heterosexual

- ^ Bright, Susie (April 14, 1992). "Men who love lesbians (who don't care for them too much)". Susie Bright's Sexual Reality: A Virtual Sex World Reader. Cleis Press. pp. 93–98. ISBN 0-939416-58-1.

- ^ a b c Ziv, Amalia (2014). "Girl meets boy: Cross-gender queer and the promise of pornography". Sexualities. 17 (7): 885–905. doi:10.1177/1363460714532937. S2CID 145460606.

Works cited

[edit]- Vieira, Mark A. (1999). Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-4475-8.

- Zimmerman, Bonnie, ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815333548.

Further reading

[edit]- Aron, Nina Renata (July 19, 2017). "This was the first pornography magazine for lesbians by lesbians—and it was a vital feminist voice". Timeline. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Books

- Bonnet, Marie-Jo (2000). Les Deux Amies: Essai sur le couple de femmes dans l'art. Paris, France: Blanche. ISBN 978-2911621949.

- Bunch, Charlotte (1982). "Lesbianism and erotica in pornographic America". In Lederer, Laura (ed.). Take back the night: women on pornography. Toronto London: Bantam. ISBN 9780553149074.

- Kitzinger, Jenny; Kitzinger, Celia (1993). ""Doing it": Representations of lesbian sex". In Griffin, Gabriel (ed.). Outwrite: Lesbianism and popular culture. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745306889.

- Rodgerson, Gillian (1993). "Lesbian erotic explorations". In Segal, Lynne; McIntosh, Mary (eds.). Sex exposed: Sexuality and the pornography debate. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 275–279. ISBN 9780813519388.

- Russo, Anne; Torres, Lourdes (2001). "Lesbian porn stories: Rebellion and/or resistance?". In Russo, Anne (ed.). Taking back our lives: A call to action for the feminist movement. New York: Routledge. pp. 101–118. ISBN 9780415927116.

- Sheldon, Caroline (1984). "Lesbians and film: Some thoughts". In Dyer, Richard (ed.). Gays and Film. New York: Zoetrope. pp. 5–26. ISBN 9780918432582.

- Journals

- Conway, Mary T. (July 1997). "Spectatorship in lesbian porn: The woman's woman's film". Wide Angle. 19 (3): 91–113. doi:10.1353/wan.1997.0011. S2CID 167693847.

- Duncker, Patricia (1995). ""Bonne excitation, Orgasme Assuré": The representation of lesbianism in contemporary French pornography". Journal of Gender Studies. 4 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1080/09589236.1995.9960588.

- Dunn, Sara (Spring 1990). "Voyages of the Valkyries: Recent lesbian pornographic writing". Feminist Review. 34 (34): 161–170. doi:10.2307/1395316. JSTOR 1395316.

- Henderson, Lisa (1991). "Lesbian pornography: Cultural transgression and sexual demystification". Women and Language. 14 (1): 3–12. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015.

- Reprinted in: Henderson, Lisa (1992). "Lesbian pornography: Cultural transgression and sexual demystification". In Munt, Sally R. (ed.). New lesbian criticism: literary and cultural readings. New York London: Harvester Wheatsheaf. pp. 173–191. ISBN 9780745011677.

- Reprinted in: Henderson, Lisa (1999). "Lesbian pornography: Cultural transgression and sexual demystification". In Gross, Larry P.; Woods, James D. (eds.). The Columbia reader on lesbians and gay men in media, society, and politics. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 506–516. ISBN 9780231104470.

- Jenefsky, Cindy; Helene Miller, Diane (July–August 1998). "Phallic intrusion: Girl–girl sex in Penthouse". Women's Studies International Forum. 21 (4): 375–385. doi:10.1016/S0277-5395(98)00042-9.

- McDowell, Kelly (September 2001). "The politics of lesbian pornography: Towards a chaotic proliferation of female sexual imagery". Xchanges. 1 (1).

- Morrison, Todd G; Tallack, Dani (2005). "Lesbian and bisexual women's interpretations of lesbian and ersatz lesbian pornography". Sexuality & Culture. 9 (2): 3–30. doi:10.1007/s12119-005-1005-x. S2CID 143930511.

- Packard, Tamara; Schraibman, Melissa (1993). "Lesbian pornography: Escaping the bonds of sexual stereotypes and strengthening our ties to one another". UCLA Women's Law Journal. 4 (2): 299–328.

- Penelope, Julia; Hoagland, Sarah Lucia (1980). "Lesbianism, sexuality and power: the patriarchy, violence and pornography". Sinister Wisdom. 15: 76–91. OCLC 70961358.

- Smyth, Cherry (Spring 1990). "The pleasure threshold: Looking at lesbian pornography on film". Feminist Review. 34 (34): 152–159. doi:10.2307/1395314. JSTOR 1395314.

- Swedberg, Deborah (Summer 1989). "What do we see when we see woman/woman sex in pornographic movies?". NWSA Journal. 1 (4): 602–616. JSTOR 4315957.

External links

[edit]- Erotic and Pornographic Art: Lesbian by Tasmin Wilton, glbtq, 2002.

- Pornographic Film and Video: Lesbian by Teresa Theophano, glbtq, 2002.

- "Kira Cochrane wishes Keira and Scarlett would stop it" by Kira Cochrane, New Statesman, February 27, 2006

- It's February; Pucker Up, TV Actresses by Virginia Heffernan, New York Times, February 10, 2005. (requires login)

- "Boogie Dykes: How two San Francisco independent filmmakers are changing the world of mainstream porn" by Michelle Tea, San Francisco Bay Guardian, January 31, 2001.

- "Celebrating Lesbian Sexuality: An Interview with Inoue Meimy, Editor of Japanese Lesbian Erotic Lifestyle Magazine Carmilla" interview by Katsuhiko Suganuma and James Welker, Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context 12, January 2006.