Generation Alpha

| Part of a series on |

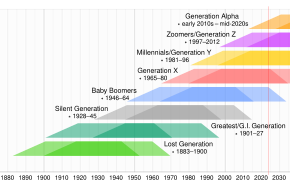

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

Generation Alpha (often shortened to Gen Alpha) is the demographic cohort succeeding Generation Z and preceding Generation Beta[1] While researchers and popular media generally identify early 2010s as the starting birth years and the mid-2020s as the ending birth years, these ranges are not precisely defined and may vary depending on the source (). Named after alpha, the first letter in the Greek alphabet, Generation Alpha is the first to be born entirely in the 21st century and the third millennium. The majority of Generation Alpha are the children of Millennials.[2][3][4][5][6]

Generation Alpha has been born at a time of falling fertility rates across much of the world,[7][8] and experienced the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic as young children. For those with access, children's entertainment has been increasingly dominated by electronic technology, social networks, and streaming services, with interest in traditional television concurrently falling. Changes in the use of technology in classrooms and other aspects of life have had a significant effect on how this generation has experienced early learning compared to previous generations. Studies have suggested that health problems related to screen time, allergies, and obesity became increasingly prevalent in the late 2010s.

Terminology

The name Generation Alpha originated from a 2008 survey conducted by the Australian consulting agency McCrindle Research, according to founder Mark McCrindle, who is generally credited with the term.[9][10] McCrindle describes how his team arrived at the name in a 2015 interview:

When I was researching my book The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations (published in 2009) it became apparent that a new generation was about to commence and there was no name for them. So I conducted a survey (we're researchers after all) to find out what people think the generation after Z should be called and while many names emerged, and Generation A was the most mentioned, Generation Alpha got some mentions too and so I settled on that for the title of the chapter Beyond Z: Meet Generation Alpha. It just made sense as it is in keeping with scientific nomenclature of using the Greek alphabet in lieu of the Latin and it didn't make sense to go back to A, after all they are the first generation wholly born in the 21st Century and so they are the start of something new not a return to the old.[11]

McCrindle Research also took inspiration from the naming of hurricanes, specifically the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season in which the names beginning with the letters of the Latin alphabet were exhausted, and the last six storms were named with the Greek letters alpha to zeta.[10]

In 2020 and 2021, some anticipated that the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic would become this generation's defining event, suggesting the name Generation C or "Coronials" for those either born during, or growing up during, the pandemic.[12][13][14][15] In light of the increasing role of artificial intelligence, it has also been proposed that this generation should be called "Generation AI".[16][17]

Psychologist Jean Twenge refers to this cohort as "Polars" in light of the growing political polarization of the United States during the 2010s and 2020s, as well as the melting of polar ice caps, a sign of (anthropogenic) climate change.[18]

Date and age range definitions

There is no consensus yet on the birth years of Generation Alpha. McCrindle, who coined the term, uses 2010–2024[19] and some other sources have followed suit,[20][21] sometimes with minor variations like 2010–2025[22] or 2011–2025.[5] Some others have used shorter ranges, such as 2011–2021[23] or 2013–2021.[24]

Other sources, while they have not specified a range for Generation Alpha, have specified end years for Generation Z of 2010,[22] 2012,[25][26][27] or 2013,[28] implying a later start year than 2010 for Generation Alpha.

Demographics

As of 2015, there were some two and a half million people born every week around the globe; Generation Alpha is expected to reach close to two billion by 2025.[29] For comparison, the United Nations estimated that the human population was about 7.8 billion in 2020, up from 2.5 billion in 1950. As of 2020, roughly three-quarters of all people reside in Africa and Asia,[30] where most human population growth is coming from, as nations in Europe and the Americas tend to have too few children to replace themselves.[31]

The number of people above 65 years of age (705 million) exceeded those between the ages of zero and four (680 million) for the first time in 2018. If current trends continue, the ratio between these two age groups will top two by 2050.[32]

Birth rates have been falling around the world due to rising standards of living, higher access to contraceptives, and more educational and economic opportunities. In fact, about half of all countries had sub-replacement fertility in the mid-2010s. The global average reproduction rate in 1950 was 4.7 but dropped to 2.4 in 2017. However, this average masks the huge variation between countries. Niger has the world's highest fertility rate at 7.1, while South Korea has one of the lowest at 0.78 (2022). In general, the more developed countries, including much of Europe, the United States, South Korea, and Australia, tend to have lower reproduction rates,[33] with people statistically having fewer children, and at later ages.[32]

Surveys conducted in developed economies suggest that women's desired family sizes tend to be higher than the one they end up building. Stagnant wages and eroding welfare programs are the contributing factors.[citation needed] While some countries like Sweden and Singapore have tried various incentives to raise their birth rates, such policies have not been particularly successful. Moreover, birth rates following the COVID-19 global pandemic might drop significantly due to economic recession.[34] Data from late 2020 and early 2021 suggests that in spite of expectations of a baby boom occurring due to COVID-19 lockdowns, the opposite ended up happening in developed nations, though developing countries were not heavily affected.[citation needed]

Education is commonly cited as one of the most important determinants. The more educated a person is, the fewer children they have, and the later the age is in which they have children.[31] At the same time, global average life expectancy has risen from 52 in 1960 to 72 in 2017.[32] Higher interest in education brings about an environment in which mortality rates fall, which in turn increases population density.[35]

Half of the human population lived in urban areas in 2007, and this figure became 55% in 2019. If the current trend continues, it will reach two thirds by the middle of the century. A direct consequence of urbanization is a falling birth rate. People in urban environments demand greater autonomy and exercise more control over their bodies.[36] In mid-2019, the United Nations estimated that the human population will reach about 9.7 billion by 2050, a downward revision from an older projection to account for faster falling fertility rates in the developing world. The global annual rate of growth has been declining steadily since the late twentieth century, dropping to about one percent in 2019.[37] By the late 2010s, 83 of the world's countries had sub-replacement fertility.[38]

During the early to mid-2010s, more babies were born to Christian families than to those of any other religion in the world, while Muslims had a faster rate of growth. About 33% of the world's babies were born to Christians who made up 31% of the global population between 2010 and 2015, compared to 31% to Muslims, whose share of the human population was 24%. During the same period, the religiously unaffiliated (including atheists and agnostics) made up 16% of the population and gave birth to 10% of the world's children.[39]

Economic trends and prospects

Effects of intensifying wealth inequality in the early twenty-first century is expected to be seen in the next generation, as parental income and educational level are positively correlated with children's success.[40] In the United States, children from families in the highest income quintile are the most likely to live with married parents (94% in 2018), followed by children of the middle class (74%) and the bottom quintile (35%).[41]

Education

In many developing countries around the world, large numbers of children could not read a simple passage in their own national languages by the age of ten, according to the World Bank. In the Congo, the Philippines, and Ethiopia, over 80% of children were in this category. In India and Indonesia, the rates were at about 50%. In China and Vietnam, the corresponding numbers were under 20%.[42]

Asia

Addressing Japan's demographic crisis and low birthrate, in 2019, the government of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe introduced a number of education reforms. Starting in October 2019, preschool education would be free for all children between the ages of three and five, and child care would be free for children under the age of two from low-income households. These programs would be funded by a consumption tax hike, from eight to ten percent. Starting April 2020, entrance and tuition fees for public as well as private universities would be waived or reduced. Students from low-income and tax-exempt families would be eligible for financial assistance to help them cover textbook, transportation, and living expenses. The whole program was projected to cost 776 billion yen (7.1 billion USD) per annum.[43]

In 2020, the government of Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc recommended a series of education reforms in order to raise the fertility rates of localities that found themselves below the replacement level, including the construction of daycare facilities and kindergartens in urban and industrial zones, housing subsidies for couples with two children in sub-replacement areas, and priority admission for children of said couples in public schools.[44]

In early 2021, the government of China announced a plan to invest more in physical education (PE) in order to make young boys "more masculine". Due to a combination of the (now rescinded) one-child policy and the traditional preference for sons, young boys are perceived by many to be overly coddled by their parents, and looked at as effeminate, delicate, and timid. In order to calm public concerns, state-controlled media published pieces downplaying gender roles and gender differences.[45]

In India, the population of Generation Alpha (those aged 0–14 years) was recorded as 346.9 million in the year 2011. By 2021, this figure slightly decreased to 336.9 million. As per the latest projections, it is estimated that the population of Generation Alpha will further decline to approximately 327 million by the year 2026.[citation needed]

Europe

In France, while year-long mandatory military service for men was abolished in 1996,[46] all citizens between 17 and 25 years of age must still participate in the Defense and Citizenship Day, when they are introduced to the French Armed Forces, and take language tests.[46] In 2019, President Emmanuel Macron introduced a similar mandatory service program for teenagers, as promised during his presidential campaign. Known as the Service National Universel or SNU, it is a compulsory civic service. Though it does not explicitly involve military training, it requires recruits to spend four weeks at a camp where they participate in a variety of activities designed to teach practical skills, personal discipline and a greater understanding of the French political system and society. The aim of this program is to promote national cohesion and patriotism, and to encourage interaction among young people of different backgrounds.[47] The SNU is due to become mandatory for all French 16 to 21 year olds by 2026.[47]

In 2023, the French government announced a two-billion-euro plan to promote biking in the country. This includes an initiative to train all primary school children on how to ride a bicycle.[48]

North America

In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a policy statement summarizing progress on developmental and neurological research on unstructured time spent by children, colloquially 'play', and noting the importance of playtime for social, cognitive, and language skills development. This is because to many educators and parents, play has come to be seen as outdated and irrelevant.[49] In fact, between 1981 and 1997, time spent by children on unstructured activities dropped by 25% due to increased amounts of time spent on structured activities. Unstructured time tended to be spent on screens at the expense of active play.[50] The statement encourages parents and children to spend more time on "playful learning", which reinforces the intrinsic motivation to learn and discover and strengthens the bond between children and their parents and other caregivers. It also helps children handle stress and prevents "toxic stress", something that hampers development. Dr. Michael Yogman, the lead author of the statement, noted that play does not necessarily have to involve fancy toys; common household items would do as well. Moreover, parents reading to children also counts as play, because it encourages children to use their imaginations.[49]

In 2019, psychiatrists from Quebec launched a campaign advocating the creation of courses on mental health for primary schoolchildren in order to teach them how to handle a personal or social crisis, and to deal with the psychological impact of the digital world. According to the Association des médecins psychiatres du Québec (AMPQ), this campaign focuses on children born after 2010, that is, Generation Alpha. In addition to the AMPQ, this movement is backed by the Fédération des médecins spécialistes du Québec (FMSQ), the Quebec Pediatric Association (APQ), the Association des spécialistes en médecine préventive du Québec (ASMPQ) and the Fondation Jeunes en Tête.[51][52]

Although the Common Core standards, an education initiative in the United States, eliminated the requirement that public elementary schools teach cursive writing in 2010, lawmakers from many states, including Illinois, Ohio, and Texas, have introduced legislation to teach it in theirs in 2019.[53] Some studies point to the benefits of handwriting – print or cursive – for the development of cognitive and motor skills as well as memory and comprehension. For example, one 2012 neuroscience study suggests that handwriting "may facilitate reading acquisition in young children."[54] Cursive writing has been used to help students with learning disabilities, such as dyslexia, a disorder that makes it difficult to interpret words, letters, and other symbols.[55] Unfortunately, lawmakers often cite these studies out of context, conflating handwriting in general with cursive handwriting.[53] In any case, some 80% of historical records and documents of the United States, such as the correspondence of Abraham Lincoln, were written by hand in cursive, and students today tend to be unable to read them.[56] Historically, cursive writing was regarded as a mandatory, almost military, exercise. But today, it is thought of as an art form by those who pursue it, both adults and children.[54]

In 2013, less than a third of American public schools had access to broadband Internet service, according to the non-profit EducationSuperHighway. By 2019, however, that number reached 99%. This has increased the frequency of digital learning.[57]

Since the early 2010s, a number of U.S. states have taken steps to strengthen teacher education. Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas had the top programs in 2014. Meanwhile, Rhode Island, which previously had the nation's lowest bar on who can train to become a school teacher, has been admitting education students with higher and higher average SAT, ACT, and GRE scores. As of 2014, the state aimed by 2020 to accept only those with standardized test scores in the top third of the national distribution, similar to Finland and Singapore.[58]

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 63% of American fourth graders could read at the basic level in 2022, which is lower than previous years of assessment, dating back to 2005.[59] Nevertheless, scores have been in decline even before the COVID-19 pandemic.[60] Taking advantage of the latest advances in the neuroscience of reading, some instructors have returned to the teaching of phonics to help rectify this problem,[60] with support from the parents and their state governments.[61][62]

According to Jill Barshay of Heschinger Report, because U.S. fertility rates never recovered after the 2007–2008 Great Recession, those born in the late 2000s and onward will likely face less competition getting accepted to colleges and universities.[63]

Health and welfare

Allergies

While food allergies have been observed by doctors since ancient times and virtually all foods can be allergens, research by the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota found that they have become increasingly common since the early 2000s. By the late 2010s, one in twelve American children had a food allergy, with peanut allergy being the most prevalent type. Reasons for this remain poorly understood.[64] Nut allergies in general quadrupled and shellfish allergies increased 40% between 2004 and 2019. In all, about 36% of American children have some kind of allergy. By comparison, this number among the Amish in Indiana is 7%. Allergies have also risen ominously in other Western countries. In the United Kingdom, for example, the number of children hospitalized for allergic reactions increased by a factor of five between 1990 and the late 2010s, as did the number of British children allergic to peanuts. In general, the better developed the country, the higher the rates of allergies.[65] Reasons for this also remain poorly understood.[64] One possible explanation, supported by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is that parents keep their children "too clean for their own good." They recommend exposing newborn babies to a variety of potentially allergenic foods, such as peanut butter, before they reach the age of six months. According to this "hygiene hypothesis", such exposures give the infant's immune system some exercise, making it less likely to overreact. Evidence for this includes the fact that children living on a farm are consistently less likely to be allergic than their counterparts who are raised in the city, and that children born in a developed country to parents who immigrated from developing nations are more likely to be allergic than their parents are.[65]

Vaccinations

In the United States, public health officials were raising the alarm in the 2010s when vaccination rates dropped. Many parents thought that they did not need to vaccinate their children against diseases such as polio and measles because they had become either extremely rare or eliminated. Officials warn that infectious diseases could return if not enough people get inoculated.[66]

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that mass vaccination campaigns be suspended in order to ensure social distancing. Dozens of countries followed this advice. However, some public health experts warned that the suspension of these programs can come with serious consequences, especially in poor countries with weak healthcare systems. For children from these places, such campaigns are the only way for them to get vaccinated against various communicable diseases such as polio, measles, cholera, human papillomavirus (HPV), and meningitis. Case numbers could surge afterwards. Moreover, because of the lockdown measures, namely, the restriction of international travels and transport, some countries might find themselves running short on not just medical equipment but also vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 can inflict more damage than the people it infects and kills.[67] In fact, SARS-CoV-2 is less dangerous for infants compared to influenza or the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).[68]

Obesity and malnutrition

A report by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) released October 2019 stated that some 700 million children under the age of five worldwide are either obese or undernourished. Although there was a 40% drop in malnourishment in developing countries between 1990 and 2015, some 149 million toddlers are too short for their age, which hampers body and brain development. UNICEF's nutrition program chief Victor Aguayo said, "A mother who is overweight or obese can have children who are stunted or wasted." About one in two youngsters suffer from deficiencies of vitamins and minerals. Although pediatricians and nutritionists recommend exclusive breastfeeding for infants below five months of age, only about 40% were. Meanwhile, the sale of formula milk jumped 40% globally. In advanced developing countries such as Brazil, China, and Turkey, that number is 75%. Even though obesity was virtually non-existent in poor countries three decades ago, today, at least ten percent of children in them suffer from this condition. The report recommends taxes on sugary drinks and beverages and enhanced regulatory oversight of breast milk substitutes and fast foods.[69]

Problems arising from screen time

A 2015 study found that the frequency of nearsightedness had doubled in the United Kingdom within the last 50 years. Ophthalmologist Steve Schallhorn, chairman of the Optical Express International Medical Advisory Board, noted that researchers had pointed to a link between the regular use of handheld electronic devices and eyestrain. The American Optometric Association sounded the alarm in a similar vein.[70] According to a spokeswoman, digital eyestrain, or computer vision syndrome, is "rampant, especially as we move toward smaller devices and the prominence of devices increase in our everyday lives." Symptoms include dry and irritated eyes, fatigue, eye strain, blurry vision, difficulty focusing, and headaches. However, the syndrome does not cause vision loss or any other permanent damage. In order to alleviate or prevent eyestrain, the Vision Council recommends that people limit screen time, take frequent breaks, adjust the screen brightness, change the background from bright colors to gray, increase text sizes, and blink more often. The Council advises parents to limit their children's screen time as well as lead by example by reducing their own screen time in front of children.[71]

In 2019, the WHO issued recommendations on the amount young children should spend in front of a screen every day. WHO said toddlers under the age of five should spend no more than an hour watching a screen and infants under the age of one should not be watching at all. Its guidelines are similar to those introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which recommended that children under 19 months old should not spend time watching anything other than video chats. Moreover, it said children under two years old should only watch "high-quality programming" under parental supervision. However, Andrew Przybylski, who directs research at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford, told the Associated Press that "Not all screen time is created equal" and that screen time advice needs to take into account "the content and context of use." In addition, the United Kingdom's Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health said its available data was not strong enough to indicate the necessity of screen time limits. WHO said its recommendations were intended to address the problem of sedentary behavior leading to health issues such as obesity.[72]

A 2019 study published in JAMA Pediatrics investigated how screen time affected the brain structure of children aged three to five (preschoolers) using MRI scans. The test subjects—27 girls and 20 boys—took cognitive tests before their brain scans while their parents answered a questionnaire on screen time developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The researchers found that the toddlers who spent more than an hour per day in front of a screen without parental involvement showed less development in the brain's white matter, the region responsible for cognitive and linguistic skills. Lead author Dr. John Hutton, a pediatrician and clinical researcher at Cincinnati Children's Hospital, told CNN that this finding was significant because the brain develops most rapidly during the first five years of a person's life. Previous studies revealed that excessive screen time is linked to sleep deprivation, impaired language development, behavioral problems, difficulty paying attention and thinking clearly, poor eating habits, and damaged executive functions.[73][74]

Diet

In 2021, Illinois-based ingredient company FONA issued a survey about Generation Alpha that found "72% of Millennials with kids say their families are consuming plant-based meats more often." The survey also found that Generation Alpha likes international food from countries which include India, Peru, Vietnam and Morocco.[75] A 2019 research study from Linda McCartney Foods found close to 50% of Generation Alpha reducing meat consumption, with 70% reporting their schools did not offer many vegetarian or vegan school meals.[76] In 2022, newspaper columnist Avery Yale Kamila wrote that "knowing quite a few members of Gen Alpha, I predict these young people will look at Gen Z's love of vegan meals and say, 'Hold my soy milk', before showing us how veg-forward a generation can get."[77] In 2021, brand firm JDO issued a research report that found less structured mealtimes mean more snacking among Generation Alpha and that Generation Alpha prefers nutrient-dense snacks that engage the senses and are sustainable or more mindful.[78]

Climate change

Generation Alpha will be significantly more affected by climate change than older generations. It is estimated that children born in 2020 will experience up to seven times as many extreme weather events over their lifetimes, particularly heat waves, compared to people born in 1960, under current climate policy pledges.[79][80]

Use of media technologies

Information and communications technologies (ICT)

Many members of Generation Alpha have grown up using smartphones and tablets as part of their childhood entertainment, with many being exposed to devices as a soothing distraction or educational aids.[81][29] Screen time among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers has increased significantly during the 2010s. Some 90% of young children used a handheld electronic device by the age of one; in some cases, children started using them when they were only a few months old.[73] Using smartphones and tablets to access video streaming services such as YouTube Kids and free or reasonably low-budget mobile games became a popular form of entertainment for young children.[82] A report by Common Sense media suggested that the amount of time children under nine in the United States spent using mobile devices increased from 15 minutes a day in 2013 to 48 minutes in 2017.[83] Research by the children's charity Childwise suggested that a majority of British three- and four-year-olds owned an Internet-connected device by 2018.[84]

Being born into an environment where the use of electronic devices is ubiquitous comes with its own challenges: cyber-bullying, screen addiction, and inappropriate content.[2] On the other hand, much of the research on the effects of screen time on children has been inconclusive or even suggested positive effects.[85] The writer and educator Jordan Shapiro has suggested that the increasingly technological nature of childhood should be embraced as a way to prepare children for life in an increasingly digital world as well as teaching them skills for offline life.[85]

Parental internet use

Generation Alpha have also been surrounded by adult Internet use from the beginning of their lives. Their parents, primarily Millennials, are heavy social media users. A 2014 report from cybersecurity firm AVG stated that 6% of parents created a social media account and 8% an email account for their baby or toddler. According to BabyCenter, an online company specializing in pregnancy, childbirth, and child-rearing, 79% of Millennial mothers used social media on a daily basis and 63% used their smartphones more frequently since becoming pregnant or giving birth. More specifically, 24% logged on to Facebook more frequently and 33% did the same to Instagram after becoming a mother. Non-profit advocacy group Common Sense Media warned that parents should take better care of their online privacy, lest their and their children's personal information and photographs fall into the wrong hands. This warning was issued after a Utah mother reportedly found a photograph of her children on a social media post with pornographic hashtags in May 2015.[86] Nevertheless, the Millennial generation's familiarity with the online world allows them to use their personal experience to help their children navigate it.[2]

Members of Generation Z often use the term "iPad kid" when referring to Generation Alpha.[87] This term was coined due to the majority of Generation Alpha's early childhood being spent watching and interacting with tablets and other smart mobile devices with the assumption of them being addicted.[88] In 2017, a study suggested that at least 80 percent of young children had access to a smart mobile device and schoolchildren had an average screentime of around seven hours a day.[88][89] Apple iPads are one of the most popular smart mobile devices hence the name.

Television and streaming services

In part due to the surge in use of handheld devices,[29] broadcast television viewing among children has declined during the early lives of Generation Alpha. Statistics from the United States suggested that viewing of children's cable networks among American 2- to 11-year-olds were falling sharply in early 2020 and continued to do so (albeit by smaller amounts) even after COVID-19 restrictions took children out of school and kept them at home.[90] Research from the United Kingdom suggested that viewing of traditional broadcasting among British 4- to 15-year-olds fell from an average of 151 minutes in 2010 to 77 minutes in 2018.[91] However, accessing televised programming via streaming and catch up services has become increasingly popular among children during the same time period. In 2019, almost 60% of Netflix's 152 million global subscribers accessed content for children and families at least once a month.[92] In the United Kingdom, requests for children's programming on the BBC's catch up service iPlayer increased substantially during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.[93][94] In 2019, the catch-up service for Australian broadcaster ABC received more than half its views via children's content.[95]

Family and social life

Upbringing

Research from 2021 suggested that British children were allowed out to play without adult supervision almost two years later than their parents had been. The study of five- to eleven-year-olds suggested that the average age for a child to be first given that freedom was 10.7 years old whilst their parents recalled being let out noticeably earlier at an average of 8.9 years of age. Helen Dodd, a professor of child psychology at the University of Reading, who led the study commented "In the largest study of play in Britain, we can clearly see that there is a trend to be protective and to provide less freedom for our children now than in previous generations... The concerns we have from this report are twofold. First, we are seeing children getting towards the end of their primary school years without having had enough opportunities to develop their ability to assess and manage risk independently. Second, if children are getting less time to play outdoors in an adventurous way, this may have an impact on their mental health and overall wellbeing." The research also suggested that children were more likely to be allowed to play outside unsupervised at an earlier age if they were white, the second or later born, living in Scotland or had better educated parents.[96]

In the United States, the share of children living with single parents (and no other adults) continued to grow during the 2010s, reaching 23% in 2019, higher than any other country studied by the Pew Research Center, including neighbouring Canada, at 15%.[97] This has raised concern over their welfare.[98][99] On the other hand, in Asia (including the Middle East), single-parent households are extremely rare.[97] But American children of the 2010s and 2020s are much safer than ever before, thanks to children's car seats, seat-belt laws, and swimming-pool safety reforms, among other things. At the same time, their parents tend to have fewer of them and to have them later in life, after achieving financial security, and as such are in a position to devote more resources to rearing them.[18]

Major events

COVID-19 pandemic

Much of Generation Alpha lived through the global COVID-19 pandemic as young children, the oldest of them being 8 years old at the time the pandemic began in early 2020. Although they are at far less risk of becoming seriously ill with the disease than their elders,[68] this cohort is dramatically affected by the crisis in other ways.[100] Many are faced with extended periods out of school or daycare and much more time at home,[101] which raised concerns about potential harm to the development of small children and the academic attainment of those of school age[102][103][104] while putting some, especially the particularly vulnerable, at greater risk of abuse.[105] The crises also led to increased child malnutrition and increased mortality, especially in developing countries.[106]

A study of the understanding of seven- to twelve-year-olds of the pandemic in the UK, Spain, Canada, Sweden, Brazil and Australia found that more than half of children knew a significant amount about COVID-19. They associated the topic with various negative emotions saying it made them feel "worried", "scared", "angry" and "confused". They tended to be aware of the types of people which were most vulnerable to the virus and the restrictions which were enforced in their communities. Many had learned new terms and phrases in relation to the pandemic such as social distancing. They were most commonly informed about COVID-19 by teachers and parents, but also learned about the subject from friends, television and the Internet.[107]

A report by UNICEF in late 2021 described the COVID-19 pandemic as "the biggest threat to children in our 75-year history." It noted that amongst other effects, levels of child poverty and malnutrition had sharply increased. Education and the services designed to protect vulnerable children had been disrupted across the world. Child labour rates had increased, reversing a 20-year fall.[108]

While children were at less direct risk in general from COVID-19, the disease was nevertheless a top-ten cause of death for children during the most acute phases of the pandemic. In the United States, it was the sixth leading cause of death for children in 2021[109] and the eighth in 2023.[110] The CDC reported that, globally, 10.5 million children had been orphaned by COVID-19.[111]

Projections of demographic changes

The first wave of Generation Alpha will reach adulthood by the 2030s. It was predicted in 2018 that, by that time, the world population is expected to be just under nine billion, and the world will have the highest ever proportion of people aged over 60,[112] meaning this demographic cohort will bear the burden of an aging population.[3] According to Mark McCrindle, a social researcher from Australia, Generation Alpha will most likely delay standard life markers such as marriage, childbirth, and retirement, as did the previous generations. McCrindle estimated that Generation Alpha will make up 11% of the global workforce by 2030.[3] He also predicted that they will live longer and have smaller families, and will be "the most formally educated generation ever, the most technology-supplied generation ever, and globally the wealthiest generation ever."[29]

In 2018, the United Nations forecasted that while the global average life expectancy would rise from 70 in 2015 to 83 in 2100, the ratio of people of working age to senior citizens would shrink due to falling fertility rates worldwide. By 2050, many nations in Asia, Europe, and Latin America would have fewer than two workers per retiree. U.N. figures show that, leaving out migration, all of Europe, Japan, and the United States were shrinking in the 2010s, but by 2050, 48 countries and territories would experience a population decline.[113]

As of 2020, the latest demographic projections from the United Nations predict that there would be 8.5 billion people by 2030, 9.7 billion by 2050, and 10.9 billion by 2100. U.N. calculations assume countries with especially low fertility rates will see them rise to an average of 1.8 per woman. However, a 2020 study by researchers from Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington, published in the Lancet projected there would only be about 8.8 billion people by 2100, two billion fewer than what the U.N. predicted. This was because their analysis suggested that as educational opportunities and family planning services become more and more accessible for women, they would choose to have no more than 1.5 children on average. A majority of the world's countries would continue to see their fertility rates decline, the researchers claimed. In particular, over 20 countries—including China, Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Poland—would find their populations reduced by around half or more. Meanwhile, sub-Saharan Africa would continue to experience a population boom, with Nigeria reaching 800 million people by century's end. Lower-than-expected human population growth means less stress on the environment and on food supplies, but it also points to a bleak economic picture for the greying countries. For the sub-Saharan African countries, though, there would be considerable opportunity for growth. The researchers predicted that as the century unfolds, major but aging economies such as Brazil, Russia, Italy, and Spain would shrink while Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom would remain within the top ten. India would eventually claim the third spot. China would displace the United States as the largest economy in the world by mid-century, but would return to second place later on.[114]

A 2017 projection by the Pew Research Center suggests that between 2015 and 2060, the human population would grow by about 32%. Among the major religious groups, only Muslims (70%) and Christians (34%) are above this threshold and as such would have a higher share of the global population than they do now, especially Muslims. Hindus (27%), Jews (15%), followers of traditional folk religions (5%), and the religiously unaffiliated (3%) would grow in absolute numbers, but would be in relative decline because their rates of growth are below the global average. On the other hand, Buddhists would find their numbers shrink by 7% during the same period. This is due to sub-replacement fertility and population aging in Buddhist-majority countries such as China, Japan, and Thailand. This projection has taken into account religious switching. Moreover, previous research suggests that switching plays only a minor role in the growth or decline of religion compared to fertility and mortality.[39]

See also

References

- ^ Cross, Greta. "Welcome Gen Beta: A new generation of humanity starts in 2025". USA TODAY. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c Shaw Brown, Genevieve (February 17, 2020). "After Gen Z, meet Gen Alpha. What to know about the generation born 2010 to today". Family. ABC News. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Perano, Ursula (August 8, 2019). "Meet Generation Alpha, the 9-year-olds shaping our future". Axios. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Carter, Christine Michel. "The Complete Guide To Generation Alpha, The Children Of Millennials". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Lavelle, Daniel (January 4, 2019). "Move over, millennials and Gen Z – here comes Generation Alpha". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Kircher, Madison Malone (November 8, 2023). "Gen Alpha Is Here. Can You Understand Their Slang?". The New York Times.

- ^ Gallagher, James (February 15, 2020). "Fertility rate: 'Jaw-dropping' global crash in children being born". BBC. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Bricker, Darrell (June 15, 2021). "Bye, bye, baby? Birthrates are declining globally – here's why it matters". World Economic Forum. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Pinsker, Joe (February 21, 2020). "Oh No, They've Come Up With Another Generation Label". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ a b McCrindle, Mark; Wolfinger, Emily (2009). The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations (1st ed.). Australia. pp. 199–212. ISBN 978-1-74223-035-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) See excerpt "Why we named them Gen Alpha". - ^ "Generation Alpha: Mark McCrindle Q & A with the New York Times". mccrindle.com.au. September 22, 2015. Archived from the original on March 14, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2020. Quote is an outtake from the New York Times story.

- ^ Yancey-Bragg, N'dea (May 3, 2020). "Coronavirus will define the next generation: What experts are predicting about 'Generation C'". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Yong, Ed (March 25, 2020). "How the Pandemic Will End". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Shoichet, Catherine E. (March 11, 2021). "Meet Gen C, the Covid generation". CNN. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Words We're Watching: 'Coronial'". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Owyoung, Palmer (May 23, 2023). "Generation AI Part 1- Why We Should be More Afraid of Techno-Oligarchs than a Rogue AI (for now)".

- ^ "Generation AI | UNICEF Office of Innovation". www.unicef.org.

- ^ a b Twenge, Jean (2023). "Chapter 8: Polars". Generations: The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X and Silents—and What They Mean for America's Future. New York: Atria Books. ISBN 978-1-9821-8161-1.

- ^ "Understanding Generation Alpha". mccrindle.com.au. July 6, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- ^ "Marketing to Generation Alpha, the Newest and Youngest Cohort". www.ana.net. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Dedczak, Michele (November 17, 2021). "Everything You Need to Know About Generation Alpha—The Children of Millennials". www.mentalfloss.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Carter, Christine Michel. "The Complete Guide To Generation Alpha, The Children Of Millennials". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "2021 Census shows Millennials overtaking Boomers | Australian Bureau of Statistics". www.abs.gov.au. June 28, 2022. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 27, 2022). "A generational portrait of Canada's aging population from the 2021 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Dimmock, Michael (January 17, 2019). "Defining generations: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ Hecht, Evan. "What years are Gen X? Here's the full list of when each generation was born". USA TODAY. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Frey, William H. (July 30, 2020). "Now, more than half of Americans are millennials or younger". Brookings. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Bennett, Neil; Hays, Donald; Sullivan, Briana (August 1, 2022). "2019 Data Show Baby Boomers Nearly 9 Times Wealthier Than Millennials". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Alex (September 19, 2015). "Meet Alpha: The Next 'Next Generation'". Fashion. The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ Barry, Sinead (June 19, 2019). "Fertility rate drop will see EU population shrink 13% by year 2100; active graphic". World. Euronews. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ a b AFP (November 10, 2018). "Developing nations' rising birth rates fuel global baby boom". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c Duarte, Fernando (April 8, 2018). "Why the world now has more grandparents than grandchildren". Generation Project. BBC News. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ Gallagher, James (November 9, 2018). "'Remarkable' decline in fertility rates". Health. BBC News. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ Safi, Michael (July 25, 2020). "All the people: what happens if humanity's ranks start to shrink?". World. The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Wodarz, Dominik; Stipp, Shaun; Hirshleifer, David; Komarova, Natalia L. (April 15, 2020). "Evolutionary dynamics of culturally transmitted, fertility-reducing traits". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287 (1925). doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2468. PMC 7211447. PMID 32290801.

- ^ Bricker, Darrell; Ibbitson, John (January 27, 2019). "What goes up: are predictions of a population crisis wrong?". The Observer. The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "The UN revises down its population forecasts". Demography. The Economist. June 22, 2019. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ Lopez, Rachel (February 29, 2020). "Baby monitor: See how family size is shrinking". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Changing Global Religious Landscape". Religion. Pew Research Center. April 5, 2017. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Claire Cain; Bui, Quoctrung (February 27, 2016). "Equality in Marriages Grows, and So Does Class Divide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 24, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Reeves, Richard V.; Pulliam, Christopher (March 11, 2020). "Middle class marriage is declining, and likely deepening inequality". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Most children in poor countries are being failed by their schools". The Economist. January 26, 2023. Archived from the original on January 26, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Japan enacts legislation making preschool education free in effort to boost low fertility rate". National. Japan Times. May 10, 2019. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Viet Tuan (May 5, 2020). "Marry early, have kids soon, Vietnam urges citizens". VN Express International. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ "Chinese plan to boost 'masculinity' with PE classes sparks debate". Reuters. February 3, 2021. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Davies, Pascale (June 27, 2018). "On Macron's orders: France will bring back compulsory national service". France. EuroNews. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Villeminot, Florence (July 11, 2019). "National civic service: A crash course in self-defence, emergency responses and French values". French Connection. France 24. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ De Clercq, Geert (May 5, 2023). "France to spend 2 billion euros to boost bicycle usage". Reuters. Archived from the original on May 7, 2023. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Klass, Perri (August 20, 2018). "Let Kids Play – Doctors should prescribe playtime for young children, the American Academy of Pediatrics says". The Checkup. The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Burdette, Hillary; Whitaker, Robert (January 2005). "Resurrecting Free Play in Young Children Looking Beyond Fitness and Fatness to Attention, Affiliation, and Affect". JAMA Pediatrics. 159 (1): 46–50. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.1.46. PMID 15630057.

- ^ Canadian Press (October 25, 2019). "Urgent need to educate elementary-aged children about mental health: Quebec psychiatrists". Montreal. CTV News. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ Canadian Press (October 25, 2019). "Mental health courses should be taught in grade school: Quebec psychiatrists". Local News. Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Rueb, Emily (April 13, 2019). "Cursive Seemed to Go the Way of Quills and Parchment. Now It's Coming Back". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Keller, Helen (September 2, 2018). "From punishing to pleasurable, how cursive writing is looping back into our hearts". Style. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ Elmasry, Faiza (April 15, 2019). "Handwriting Helps Kids with Learning Disabilities Read Better". VOA News. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ Bruno, Debra (June 17, 2019). "The National Archives has billions of handwritten documents. With cursive skills declining, how will we read them?". Magazine. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ Mathewson, Tara Garcia (October 23, 2019). "Nearly all American classrooms can now connect to high-speed internet, effectively closing the "connectivity divide"". Future of Learning. Hechinger Report. Archived from the original on November 10, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Ripley, Amanda (June 17, 2014). "To improve our schools, we need to make it harder to become a teacher". Slate. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ "NAEP Reading: National Achievement-Level Results". Nation's Report Card. NAEP. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Barshay, Jill; Flynn, Hillary; Sheasley, Chelsea; Richman, Talia; Bazzaz, Dahlia; Griesbach, Rebecca (November 10, 2021). "America's reading problem: Scores were dropping even before the pandemic". Elementary to High School. Hechinger Report. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Schwartz, Sarah (February 28, 2023). "The 'Science of Reading' Will Be a Big Topic at SXSW EDU. Get Prepped With 3 Things to Know". Education Week. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Heather (April 20, 2023). "An end to the reading wars? More US schools embrace phonics". Associated Press. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Barshay, Jill (September 10, 2018). "College students predicted to fall by more than 15% after the year 2025". Hechinger Report. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Graphic Detail (October 3, 2019). "The prevalence of peanut allergy has trebled in 15 years". Daily Chart. The Economist. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ a b "Why everybody is suddenly allergic to everything". Health. National Post. July 30, 2019. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Szabo, Liz (February 24, 2020). "Old diseases, other public health threats reemerge in the U.S." Health. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Leslie (April 9, 2020). "Polio, measles, other diseases set to surge as COVID-19 forces suspension of vaccination campaigns". Science Magazine. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Makin, Simon (February 2024). "Infant Power: What's behind babies' COVID-fighting prowess?". Scientific American: 14.

- ^ "1-in-3 young children undernourished or overweight: UNICEF". AFP. October 15, 2019. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Stevens, Heidi (July 16, 2015). "Too much screen time could be damaging kids' eyesight". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ Hellmich, Nanci (January 25, 2014). "Digital device use leads to eye strain, even in kids". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ "UN: No screen time for babies; only 1 hour for kids under 5". Associated Press. April 24, 2019. Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b LaMotte, Sandee (November 4, 2019). "MRIs show screen time linked to lower brain development in preschoolers". CNN. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Hutton, John S.; Dudley, Jonathan; Horowitz-Kraus, Tzipi (November 4, 2019). "Associations Between Screen-Based Media Use and Brain White Matter Integrity in Preschool-Aged Children". JAMA Pediatrics. 174 (1). Archived from the original on August 31, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "All About the Kids: Part I; Generational Comparisons & Their Flavor Favorites". FONA. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ GenerationAhead. "What are Alphas Eating?". GENERATION ALPHA. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Kamila, Avery Yale (August 7, 2022). "More plant-based foods partner with pop culture icons". Portland Press Herald. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "Know your audience: what Gen Alpha's food habits tell us about this unique generation". Creative Boom. December 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Gramling, Carolyn (October 1, 2021). "2020 babies may suffer up to seven times as many extreme heat waves as 1960s kids". Science News. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ Thiery, Wim; Lange, Stefan; Rogelj, Joeri; Schleussner, Carl-Friedrich; Gudmundsson, Lukas; Seneviratne, Sonia I.; Andrijevic, Marina; Frieler, Katja; Emanuel, Kerry; Geiger, Tobias; Bresch, David N.; Zhao, Fang; Willner, Sven N.; Büchner, Matthias; Volkholz, Jan; Bauer, Nico; Chang, Jinfeng; Ciais, Philippe; Dury, Marie; François, Louis; Grillakis, Manolis; Gosling, Simon N.; Hanasaki, Naota; Hickler, Thomas; Huber, Veronika; Ito, Akihiko; Jägermeyr, Jonas; Khabarov, Nikolay; Koutroulis, Aristeidis; Liu, Wenfeng; Lutz, Wolfgang; Mengel, Matthias; Müller, Christoph; Ostberg, Sebastian; Reyer, Christopher P. O.; Stacke, Tobias; Wada, Yoshihide (October 8, 2021). "Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes". Science. 374 (6564): 158–160. Bibcode:2021Sci...374..158T. doi:10.1126/science.abi7339. PMID 34565177. S2CID 237942847.

- ^ Sterbenz, Christina. "Here's who comes after Generation Z — and they'll be the most transformative age group ever". Business Insider. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Children and parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report" (PDF). Ofcom. November 29, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 15, 2020.

- ^ Howard, Jacqueline (October 19, 2017). "Report: Young kids spend over 2 hours a day on screens". CNN. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ Turner, Camilla (October 4, 2018). "Majority of three and four-year-olds now own an iPad, survey finds". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Cunliffe, Rachel (March 2, 2021). "Is growing up immersed in screens damaging our children?". New Statesman. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Bowen, Alison (October 20, 2015). "Do newborns need their own websites, email, social media accounts?". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ "The Infamous iPad Kid | IST 110: Introduction to Information Sciences and Technology". sites.psu.edu. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Hendy, Eloise (November 21, 2023). "iPad Kids Are Getting Out of Hand". Vice. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Travers, Mark. "A Psychologist Teaches Parents How To Fix An 'iPad Kid'". Forbes. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Low, Elaine (April 9, 2020). "Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network and other kids cable channels see viewership declines as streaming grows". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Ofcom's Annual Report on the BBC: 2017/18" (PDF). Ofcom. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (October 11, 2019). "Netflix Goes All Out to Wow Children as Streaming Wars Intensify". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Record number of kids come to the BBC during lockdown". BBC. July 22, 2020. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Record number of kids turn to the BBC for education and entertainment". BBC. January 20, 2021. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Cameron (February 19, 2019). "Dog days for Australian kids' television". Crikey. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ Weale, Sally (April 20, 2021). "UK children not allowed to play outside until two years older than parents' generation". the Guardian. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Kramer, Stephanie (September 12, 2019). "U.S. has world's highest rate of children living in single-parent households". Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Irwin, Neil (September 18, 2023). "New book shows economic downside of single parenting". Axios. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Gogoi, Pallavi (October 22, 2023). "Why children of married parents do better, but America is moving the other way". National Public Radio. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Lloyd, Robin (July 20, 2020). "What Is It That Keeps Most Little Kids From Getting Covid-19?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 8, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (March 27, 2020). "1.5 billion children around globe affected by school closure. What countries are doing to keep kids learning during pandemic". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus #4: From the perspective of a baby or young child". Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 is hurting children's mental health. Here's how to help". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on September 5, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Robson, David (June 3, 2020). "How Covid-19 is changing the world's children". BBC Future. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Joint Leaders' statement - Violence against children: A hidden crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic". www.who.int. April 8, 2020. Archived from the original on August 23, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 and children". UNICEF DATA. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "We asked children around the world what they knew about COVID. This is what they said". March 1, 2021. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "PREVENTING A LOST DECADE: Urgent action to reverse the devastating impact of COVID-19 on children and young people" (PDF). Unicef. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Piore, Adam (October 27, 2021). "COVID Now a 'Major Cause of Death' in Kids But Parents Hesitant on Vaccine". Newsweek. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ Flaxman, Seth; Whittaker, Charles; Semenova, Elizaveta; Rashid, Theo; Parks, Robbie M.; Blenkinsop, Alexandra; Unwin, H. Juliette T.; Mishra, Swapnil; Bhatt, Samir; Gurdasani, Deepti; Ratmann, Oliver (January 30, 2023). "Assessment of COVID-19 as the Underlying Cause of Death Among Children and Young People Aged 0 to 19 Years in the US". JAMA Network Open. 6 (1): e2253590. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.53590. hdl:10044/1/102011. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 9887489. PMID 36716029.

- ^ "Global Orphanhood Associated with COVID-19 | CDC". www.cdc.gov. February 6, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ Catchpole, Suzi (June 21, 2019). "Move over Millennials, it's Generation Alpha's turn". Stuff. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Levine, Steve; Stevens, Harry (July 21, 2018). "Deep Dive: The aging, childless future". Politics and Policy. Axios. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ AFP (July 15, 2020). "World population in 2100 could be 2 billion below UN projections". France 24. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

External links

- Why your smartphone is irresistible (and why it's worth trying to resist). Psychologist Adam Alter on the PBS Newshour. April 21, 2017.

- The Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development in Young Children. Michael Yogman, Andrew Garner, Jeffrey Hutchinson, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Children and Family Health, Council on Communications and Media, American Academy of Pediatrics. September 2018.

- A 'million word gap' for children who aren't read to at home. Jessica A. R. Logan, Laura M. Justice, Melike Yumuş, Leydi Johana Chaparro-Moreno. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. April 4, 2019.

- Population pyramids of the EU-27 without France and of France in 2020. Population pyramids of the developed world without the U.S. and of the U.S. in 2030. Zeihan on Geopolitics.