United States occupation of Haiti

| United States occupation of Haiti | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Banana Wars | |||||||

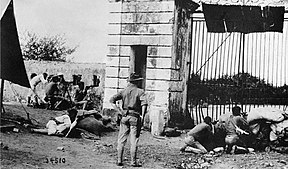

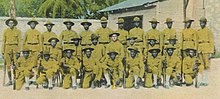

Top to bottom, left to right: United States Marines in 1915 defending entrance gate in Cap-Haïtien, United States Marines and a Haitian guide patrolling the jungle during the Battle of Fort Dipitie, United States Navy Curtiss HS-2Ls and other airplanes in Haiti circa 1919 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

First Caco War: 1,500 US Marines[1] 2,700 Haitian Gendarmes[1] |

First Caco War: 5,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

First Caco War: 146 American deaths[2] |

First Caco War: 2,000+ killed[1] | ||||||

|

3,250–15,000 Haitian deaths[3][4] Hundreds to 5,500 forced labor deaths[5] | |||||||

| History of Haiti |

|---|

| Pre-Columbian Haiti (before 1492) |

| Captaincy General of Santo Domingo (1492–1625) |

| Taíno genocide |

| Saint-Domingue (1625–1804) |

| First Empire of Haiti (1804–1806) |

| North Haiti (1806–1820) |

| South Haiti (1806–1820) |

| Republic of Haiti (1820–1849) |

| Second Empire of Haiti (1849–1859) |

| Republic of Haiti (1859–1957) |

| Duvalier dynasty (1957–1986) |

| Anti-Duvalier protest movement |

| Republic of Haiti (1986–present) |

| Timeline |

| Topics |

|

|

The United States occupation of Haiti began on July 28, 1915, when 330 US Marines landed at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after the National City Bank of New York convinced the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, to take control of Haiti's political and financial interests. The July 1915 occupation took place following years of socioeconomic instability within Haiti that culminated with the lynching of President of Haiti Vilbrun Guillaume Sam by a mob angered by his decision to order the executions of political prisoners.

During the occupation, Haiti had three new presidents while the United States ruled as a military regime through martial law led by Marines and the Gendarmerie. A corvée system of forced labor was used by the United States for infrastructure projects, resulting in hundreds to thousands of deaths.[6] Under the occupation, most Haitians continued to live in poverty, while American personnel were well compensated.[citation needed] The American occupation ended the constitutional ban on foreign ownership of land, which had existed since the foundation of Haiti.

The occupation ended on August 1, 1934, after President Franklin D. Roosevelt reaffirmed an August 1933 disengagement agreement. The last contingent of marines departed on August 15, 1934, after a formal transfer of authority to the American-created Gendarmerie of Haiti.

Background

[edit]In the late 1700s, the relationship between Haitians and the United States began when some Haitians fought beside Americans in the American Revolutionary War.[7] Originally the wealthiest region in the Americas when it was the French colony of Saint-Domingue,[8][9] a slave revolt at the colony beginning in 1791 that led to the successful Haitian Revolution in 1804 frightened those living in the Southern United States who supported slavery, raising fears that it would inspire other slaves.[7][10] Such sentiments among wealthy slaveholding Americans strained relations between the United States and Haiti, with the United States initially refusing to recognize Haitian independence while slaveholders advocated for a trade embargo with the newly created Caribbean nation.[10] The Haiti indemnity controversy – which France forced upon Haiti through gunboat diplomacy in 1825 due to France's financial loss following Haiti's independence – resulted with Haiti using much of its revenue to pay debt to foreign nations by the late-1800s.[11]

The United States had been interested in controlling Haiti in the decades following its independence from France.[12] As a way "to secure a US defensive and economic stake in the West Indies", according to the United States Department of State, President Andrew Johnson of the United States began the pursuit of annexing Hispaniola, including Haiti, in 1868.[12] In 1890, the Môle Saint-Nicolas affair occurred when President Benjamin Harrison, on the advice of Secretary of State James G. Blaine, ordered Rear-Admiral Bancroft Gherardi to persuade newly assumed President of Haiti Florvil Hyppolite to lease the port to the United States.[13][14] Enforcing gunboat diplomacy upon Haiti, Gherardi aboard USS Philadelphia along with his fleet arrived in the capital city of Port-au-Prince to demand the acquisition of Môle Saint-Nicolas.[14] President Hyppolite refused any agreement as Haitians grew angered by the presence of the fleet, with The New York Times writing that the Haitians' "semi-barbaric minds saw in it a threat of violence".[13][14] Upon returning to the United States in 1891, Gherardi said in an interview with The New York Times that in a short time Haiti would experience further instability, suggesting that future governments in Haiti would abide by the demands of the United States.[13]

By the 1890s, Haiti became reliant on importing most of its goods from the United States while it exported the majority of its production to France.[15] The Roosevelt Corollary also affected Haiti's relationship with the United States.[16] By 1910, President William Howard Taft attempted to introduce American businesses to Haiti in order to deter European influence and granted a large loan to Haiti to pay off foreign debts, though this proved to be fruitless due to the size of the debt.[12][17]

German presence

[edit]

The United States was not concerned by France's influence, though German influence in Haiti raised concern.[12] Germany had intervened in Haiti, including the Lüders affair in 1897, and had been influencing other Caribbean nations during the previous few decades. Germany had also become increasingly hostile to United States domination of the region under the Monroe Doctrine.

The United States' concern over Germany's ambitions was mirrored by apprehension and rivalry between American businessmen and the small German community in Haiti, which, although numbering only about 200 in 1910, wielded a disproportionate amount of economic power.[18] German nationals controlled about eighty percent of the country's international commerce.[citation needed] They owned and operated utilities in Cap-Haïten and Port-au-Prince, including the main wharf and a tramway in the capital, and also had built the railway serving the Plain of the Cul-de-Sac.[19]

The German community was more willing to integrate into Haitian society than any other group of European foreigners, including the more numerous French. Some Germans had married into Haiti's most prominent mixed-race families of African-French descent. This enabled them to bypass the constitutional prohibition against foreigners owning land. The German residents retained strong ties to their homeland and sometimes aided the German military and intelligence networks in Haiti. They also served as the principal financiers of the nation's numerous revolutions, floating loans at high interest rates to the competing political factions.[19]

In the lead-up to World War I, the strategic importance of Haiti, along with the German influence there, worried President Wilson, who feared a German presence near the Panama Canal Zone.[10]

Haitian instability

[edit]In the first decades of the 20th century, Haiti experienced great political instability and was heavily in debt to France, Germany, and the United States.[10][20] The Wilson administration viewed Haiti's instability as a national security threat to the United States.[17] Political tensions were often between two groups; wealthy French-speaking mulatto Haitians who represented the minority of the population and poor Afro-Haitians who spoke Haitian Creole.[21] Various revolutionary armies carried out the coups. Each was formed by cacos, peasant militias from the mountains of the north, who stayed along the porous Dominican border and were often funded by foreign governments to stage revolts.[21]

In 1902, a civil war was fought between the government of Pierre Théoma Boisrond-Canal and General Pierre Nord Alexis against rebels of Anténor Firmin,[5] which led to Pierre Nord Alexis becoming president. In 1908, he was forced from power and a series of short lived presidencies came and went:[22][23] his successor François C. Antoine Simon in 1911;[24] President Cincinnatus Leconte (1911–1912) was killed in a (possibly deliberate) explosion at the National Palace;[25] Michel Oreste (1913–1914) was ousted in a coup, as was his successor Oreste Zamor in 1914.[26] Between 1911 and 1915, Haiti had seven presidents because of political assassinations, coups and forced exiles.[12][27]

American financial interests

[edit]Prior to the intervention of the United States, Haiti's large debt was 80 percent of its annual revenue, though it was able to meet financial obligations, especially when compared to Ecuador, Honduras, and Mexico at that time.[10][17] In the twentieth century, the United States had become Haiti's largest trade partner, replacing France, with American businesses expanding their presence in Haiti.[10] Due to the influence of Germans within Haiti, they were regarded as a threat to American financial interests,[28] with businesses ultimately advocating for policies of invading Haiti.[10] Haitian authorities in 1903 began to accuse the National Bank of Haiti of fraud and by 1908, Haitian Minister of Finance Frédéric Marcelin pushed for the bank to work on the behalf of Haitians, though French officials began to devise plans to reorganize their financial interests.[29] French envoy to Haiti Pierre Carteron wrote following Marcelin's objections that "It is of the highest importance that we study how to set up a new French credit establishment in Port-au-Prince ... Without any close link to the Haitian government."[29]

Businesses from the United States had pursued the control of Haiti for years and in 1909, the new president of National City Bank of New York, Frank A. Vanderlip, began to plan the bank's take over of Haiti's finances as part of his larger role of making the bank grow in international markets.[15][30][31] In early 1909, Speyer & Co. promoted a stock to Vanderlip and the bank to invest in the National Railroad of Haiti, which held a monopoly of importing in the Port-au-Prince area.[20] The Haitian government faced conflict with the National City Bank over the railroad regarding payments to creditors, later leading to the bank seeking to control the entirety of Haiti's finances.[15] Vanderlip wrote to Chairman of National City Bank James Stillman in 1910, "In the future, this stock will give us a foothold [in Haiti] and I think we will perhaps later undertake the reorganization of the Government’s currency system, which, I believe, I see my way clear to do with practically no monetary risk".[32] From 1910 to 1911, the United States Department of State backed a consortium of American investors – headed by the National City Bank of New York – to acquire a managing stake of the National Bank of Haiti to create the Bank of the Republic of Haiti (BNRH), with the new bank often holding payments from the Haitian government, leading to unrest.[30][29][28][7] France would also keep a stake in the BNRH.[29] The BNRH was the country's sole commercial bank and served as the Haitian government's treasury.[28]

Officials of the Wilson administration were not knowledgeable about Haiti and often relied on information from American businessmen.[21] United States Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan fired established Latin American experts upon his nomination and instead replaced them with political allies.[17] Bryan initially proposed forgiving the debt of Caribbean nations, though President Wilson viewed this as too radical.[17] With his ideas facing rejection, Bryan, who had little information on Haiti, instead relied on the vice president of National City Bank, Roger Leslie Farnham, for information regarding Haiti.[7][10][17][20][21] Farnham had an extensive background working as a financial advisor, lobbyist, journalis, and purchasing agent between the United States and the Caribbean, with American historian Brenda Gayle Plummer writing "Farnham ... is often portrayed by historians as the deus ex machina single-handedly plotting the American intervention of 1915".[20][33] Throughout the 1910s, Farnham demanded successive Haitian governments to grant him control of the nation's customs, the only source of revenue, threatening American intervention when Haiti refused citing national sovereignty.[17] John H. Allen, manager of the BNRH, also met with Bryan for consultation in 1912, with Allen later sharing an account of Bryan being surprised about Haitian culture and stating "Dear me, think of it! Niggers speaking French".[7][17]

In 1914, France began to lose its ties to Haiti as it was focusing its efforts on World War I and Farnham suggested to the United States Congress that the BNRH's "active management has been from New York".[7][15] Allen later stated that if the United States permanently occupied Haiti, he supported National City Bank acquiring all shares of BNRH, believing that it would "pay 20% or better".[20] Farnham persuaded Secretary Bryan to have the United States invade Haiti during a telephone call on January 22, 1914.[20] Farnham argued that Haiti was not improving due to continuous internal conflict, that Haitians were not interested in the revolts occurring and that American troops would be welcomed in Haiti.[20] Farnham also exaggerated the role of European influence, even convincing Secretary Bryan that France and Germany – two nations then at war with each other – were plotting in cooperation to obtain the harbor of Môle Saint-Nicholas in northern Haiti.[10][17][21] The businessman concluded that Haiti would not improve "until such time as some stronger outside power steps in".[20] American diplomats would ultimately draft plans to take over Haiti's finances, dubbed the "Farnham Plan".[7]

After American officials travelled to Haiti to propose the "Farnham Plan", Haitian legislators denounced their minister of foreign affairs, saying he was "endeavoring to sell the country to the United States" according to a telegram of the US State Department.[7] Due to Haitian opposition to the plan, the BNRH withheld funds from the Haitian government and funded rebels to destabilize the Haitian government in order to justify American intervention, generating 12% gains in interest by holding on to the funds.[7][17] On January 27, 1914, Haitian President Michel Oreste was deposed in a coup. Two generals, Charles and Oreste Zamor, seized control. In response, the USS Montana sent a marine detachment on January 29 into Port-au Prince to protect American interests.[34] On February 5, 1914, military forces from the French cruiser Conde and British HMS Lancaster also landed troops. These units agreed to leave the city and boarded their ships on February 9, 1914.[34]

BNRH's Allen telegrammed the State Department on April 8, 1914, requesting that the US Navy sail to Port-au-Prince to deter possible rebellions.[20] In the summer of 1914, the BNRH began to threaten the Haitian government that it would no longer provide payments.[20] Simultaneously, Secretary Bryan telegrammed the United States consul in Cap-Haïtien, writing that the State Department agreed with invading Haiti, telling the consul that the United States "earnestly desires successfully carrying out of Farnham's plan".[20][35]

American bankers raised fears that Haiti would default on debt payments despite consistent compliance by Haiti with loan conditions, calling for the seizure of Haiti's national bank.[10] National City Bank officials – acting on behalf of Farnham – demanded the State Department to provide military support to acquire Haiti's national reserves, with the bank arguing that Haiti had become too unstable to safeguard the assets.[7][20] Urged by the National City Bank and the BNRH, with the latter of the two already under direction of American business interests, eight United States marines walked into the national bank and took custody of Haiti's gold reserve of about US$500,000 – about the equivalent to $13,526,578 in 2021 – on December 17, 1914.[7][12][20][36] The Marines packed the gold into wooden boxes, loaded them into a wagon, and transported the gold under the protection of plainclothes clandestine soldiers lining the route to the USS Machias, which transferred its load to the National City Bank's New York City vault on 55 Wall Street.[7][20] The robbery of the gold provided the United States with a large amount of control over the Haitian government, though American businesses demanded further intervention.[10] National City Bank would go on to acquire some of its largest gains in the 1920s due to debt payments from Haiti, according to later filings to the Senate Finance Committee, with debt payments to the bank comprising 25% of Haiti's revenue.[7]

American invasion

[edit]In February 1915, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, son of a former Haitian president, took power as President of Haiti. The culmination of his repressive measures came on July 27, 1915, when he ordered the execution of 167 political prisoners, including former president Zamor, who was being held in a Port-au-Prince jail. This infuriated the population, which rose up against Sam's government as soon as news of the executions reached them. Sam, who had taken refuge in the French embassy, was lynched by an enraged mob in Port-au-Prince as soon as they learned of the executions.[37] The United States regarded the anti-American revolt against Sam as a threat to American business interests in the country, especially the Haitian American Sugar Company (HASCO). When the caco-supported anti-American Rosalvo Bobo emerged as the next president of Haiti, the United States government decided to act quickly to preserve its economic dominance.[38][verification needed]

In April 1915, Secretary Bryan expressed support for invading Haiti to President Wilson, writing "The American interests are willing to remain there, with a view of purchasing a controlling interest and making the bank a branch of the American bank – they are willing to do this provided this government takes the steps necessary to protect them and their idea seems to be that no protection will be sufficient that does not include control of the Customs House."[7][17]

On July 28, 1915, United States President Woodrow Wilson ordered 340 United States marines to occupy Port-au-Prince and the invasion took place the same day.[39][40] The Secretary of the Navy instructed the invasion commander, Rear Admiral William Banks Caperton, to "protect American and foreign" interests. Wilson also wanted to rewrite the Haitian constitution, which banned foreign ownership of land, to replace it with one that guaranteed American financial control.[41] To avoid public criticism, Wilson claimed the occupation was a mission to "re-establish peace and order ... [and] has nothing to do with any diplomatic negotiations of the past or the future," as disclosed by Rear Admiral Caperton.[42] Only one Haitian soldier, Pierre Sully, tried to resist the invasion, and he was shot dead by the Marines.[43]

American occupation

[edit]Dartiguenave presidency

[edit]US installs Dartiguenave as president

[edit]Haitian presidents were not elected by universal suffrage but rather chosen by the Senate. The American occupying authorities therefore looked to find a presidential candidate ready to cooperate with them.[44] Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave, president of the Senate and among the mulatto Haitian elite who supported the United States, agreed to accept the presidency of Haiti in August 1915 after several other candidates had refused. The United States would later go on to install more wealthy mulatto Haitians in positions of power.[45]

US takeover of Haitian institutions

[edit]

For several decades, the Haitian government had been receiving large loans from both American and French banks, and with the political chaos was growing increasingly incapable of repaying their debts. If the anti-American government of Rosalvo Bobo prevailed, there was no guarantee of debt repayment, and American businesses refused to continue investing there. Within six weeks of the occupation, US government representatives seized control of Haiti's customs houses and administrative institutions, including the banks and the national treasury. Under US government control, 40% of Haiti's national income was designated to repay debts to American and French banks.[46] In September 1915, the United States Senate ratified the Haitian-American Convention, a treaty granting the United States security and economic oversight of Haiti for a 10-year period.[47] Haiti's legislature initially refused to ratify the treaty, though Admiral Caperton threatened hold payments from Haiti until the treaty was signed.[48] The treaty gave the President of the United States the power to appoint a customs receiver general, economic advisors, public works engineers; and to assign American military officers to oversee a Haitian gendarmerie.[49] Haiti's economic functions were overseen by the United States Department of State, while the United States Navy was tasked with infrastructure and healthcare works, though the Navy ultimately held more authority.[49] Officials from the United States then wielded veto power over all governmental decisions in Haiti, and Marine Corps commanders served as administrators in the departments.[12] The original treaty was to be in effect for ten years, though an additional agreement in 1917 expanded the United States' power for twenty years.[49] For the next nineteen years, US State Department advisers ruled Haiti, their authority enforced by the United States Marine Corps.[12]

The Gendarmerie of Haiti, now known as the Garde d'Haïti, was also created and controlled by US Marines throughout the occupation, initially led by Major Smedley D. Butler.[12][48] Rear Admiral Caperton ordered his 2,500 Marines to occupy all of Haiti's districts, equipping them with airplanes, cars, and trucks.[50] Five airfields were constructed and at least three airplanes were present in Haiti.[5] Marines were tasked with multiple duties for their districts; law enforcement, tax collection, medicine distribution, and overseeing arbitration.[50]

Economically and politically, the Haitian government relied on American approval for most projects.[49] The 1915 treaty with the United States proved expensive; the Haitian government had such a limited income that it was difficult to hire public workers and officials.[49] Before utilizing any money, the Haitian government had to obtain approval from an American financial advisor and by 1918, would rely on American officials for approval of any laws due to fears of violating the treaty.[49]

First Caco War

[edit]The installation of a president without the consent of Haitians and the forced labor of the corvée system enforced upon Haitians by American forces led to opposition of the US occupation began immediately after the marines entered Haiti, creating rebel groups of Haitians who felt they were returning to slavery.[7][12][48] The rebels (called "Cacos", after a local bird sharing their ambush tactics)[51] strongly resisted American control of Haiti. The US and Haitian governments began a vigorous campaign to destroy the rebel armies. Perhaps the best-known account of this skirmishing came from Marine Major Smedley Butler, awarded a Medal of Honor for his exploits. He was appointed to serve as commanding officer of the Haitian gendarmerie. He later expressed his disapproval of the US intervention in his 1935 book War Is a Racket.

On November 17, 1915, the Marines captured Fort Rivière, a stronghold of the Caco rebels, which marked the end of the First Caco War.[52]: 201 The United States military issued two Haitian Campaign Medals to US Marine and naval personnel for service in the country during the periods 1915 and 1919–1920.

US forces new Haitian constitution

[edit]Shortly after installing Dartiguenave as president of Haiti, President Wilson pursued the rewriting of the Constitution of Haiti.[12] One of the main concerns for the United States was the ban of foreigners from owning Haitian land.[12] Early leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines had forbidden land ownership by foreigners when Haiti became independent to deter foreign influence, and since 1804, some Haitians had viewed foreign ownership as anathema.[12][53] Fearing impeachment and due to opposition of the legislature, Dartiguenave ordered the dissolution of the senate on April 6, 1916, with Major Butler and Colonel Waller enforcing new legislative elections.[48] Colonel Eli K. Cole would later assume Waller's position as commander of the Marines.[48]

The newly elected legislature of Haiti immediately rejected the constitution proposed by the United States.[12] Instead, the legislative body began drafting a new constitution of its own that was in contrast to the interests of the United States.[12][48] Under orders from the United States, President Dartiguenave dissolved the legislature in 1917 after its members refused to approve the proposed constitution, with Major Butler forcing the closing of the senate at gunpoint.[7][12][48]

Haiti's new constitution was drafted under the supervision of Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy.[7][54][55] A referendum in Haiti subsequently approved the new constitution in 1918 (by a vote of 98,225 to 768). In Roosevelt's new constitution, Haiti explicitly allowed foreigners to control Haitian land for the first time since Haiti's creation.[15][56] As a result of opposing the United States' effort of rewriting its constitution, Haiti would remain without a legislative branch until 1929.[12]

Second Caco War

[edit]

The end of the First World War in 1918 deprived the Haitians of their main ally in the liberation struggle. Germany's defeat meant its end as a menace to the US in the Caribbean, as it lost control of Tortuga. Nevertheless, the US continued its occupation of Haiti after the war, despite President Woodrow Wilson's claims at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 that he supported self-determination among other peoples.[citation needed]

At one time, at least twenty percent of Haitians had been involved in the rebellion against occupation according to Africanologist Patrick Bellegarde-Smith.[11] The strongest period of unrest culminated in a 1918 rebellion by up to 40,000 former cacos and other members of the opposition led by Charlemagne Péralte, a former officer of the dissolved Haitian army.[50][52] The scale of the uprising overwhelmed the Gendarmerie, but US Marine reinforcements helped put down the revolt. For their part, the Haitians resorted to non-conventional tactics, being severely outmatched by their occupiers.[52] Prior to his death, Péralte launched an attack on Port-au-Prince. The assassination of Péralte in 1919 solidified US Marine power over the Cacos.[52]: 211–218 [57][page needed] The Second Caco War ended with the death of Benoît Batraville in 1920,[52]: 223 who had commanded an assault on the Haitian capital that year. An estimated 2,004 Cacos were killed in the fighting, as well as several dozens of US Marines and Haitian gendarmes.[53]

Congressional investigation

[edit]

The educated elite in Haiti was L'Union Patriotique, which established ties with opponents of the occupation in the US. They found allies in the NAACP and among both white and African-American leaders.[58] The NAACP sent civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson, its field secretary, to investigate conditions in Haiti. He published his account in 1920, decrying "the economic corruption, forced labor, press censorship, racial segregation, and wanton violence introduced to Haiti by the US occupation encouraged numerous African Americans to flood the State Department and the offices of Republican Party officials with letters" calling for an end to the abuses and to remove troops.[59] Academic W. E. B. Du Bois, who had Haitian ancestry, demanded a response for the Wilson administration's actions and wrote that US troops "have no designs on the political independence of the island and no desire to exploit it ruthlessly for the take of selfish business interests".[11]

Based on Johnson's investigation, NAACP executive secretary Herbert J. Seligman wrote in the July 10, 1920, The Nation:[60]

"Military camps have been built throughout the island. The property of natives has been taken for military use. Haitians carrying a gun were for a time shot on sight. Machine guns have been turned on crowds of unarmed natives, and United States Marines have, by accounts which several of them gave me in casual conversation, not troubled to investigate how many were killed or wounded."

According to Johnson, there was only one reason why the United States occupied Haiti:[20]

"[T]o understand why the United States landed and has for five years maintained military forces in that country, why some three thousand Haitian men, women, and children have been shot down by American rifles and machine guns, it is necessary, among other things, to know that the National City Bank of New York is very much interested in Haiti. It is necessary to know that the National City Bank controls the National Bank of Haiti and is the depository for all of the Haitian national funds that are being collected by American officials, and that Mr. R. L. Farnham, vice-president of the National City Bank, is virtually the representative of the State Department in matters relating to the island republic."

Two years after Johnson published his findings, a congressional investigation began in the United States in 1922.[20] The report from Congress did not include testimony from Haitians and ignored allegations involving National City Bank of New York and US Marines.[20] Congress concluded the report by defending a continued occupation of Haiti, arguing that "chronic revolution, anarchy, barbarism, and ruin" would befall Haiti if the United States withdrew.[20] Johnson described the congressional investigation as "on the whole, a whitewash".[20]

Borno presidency

[edit]

In 1922, Dartiguenave was replaced by Louis Borno, with the US-appointed General John H. Russell, Jr. serving as High Commissioner. General Russell worked on the behalf of the United States Department of State and was authorized as the representative to carry out treaty works.[49]

National City Bank acquires BNRH

[edit]On August 17, 1922, BNRH was completely acquired by National City Bank, its headquarters was moved to New York City and Haiti's debt to France was moved to be paid to American investors.[15][31][49] Following the acquisition of BNRH, the November 1922 issue of National City Bank's employee journal No. 8 exclaimed "Bank of Haiti is Ours!"[31] According to professor Peter James Hudson, "such control represented the end of independence and, as the BNRH and the republic's gold reserve became mere entries on the ledgers of the City Bank, a sign of a return to colonial servitude".[31]

Forced labor

[edit]The Borno-Russell government oversaw the use of forced labor to expand the economy and to complete infrastructure projects.[11] Sisal was introduced to Haiti as a commodity crop, and sugar and cotton became significant exports.[61] However, efforts to develop commercial agriculture met with limited success, in part because much of Haiti's labor force was employed as seasonal workers in the more-established sugar industries of Cuba and the Dominican Republic. An estimated 30,000–40,000 Haitian laborers, known in Cuba as braceros, went annually to the Oriente Province between 1913 and 1931.[62] The Great Depression disastrously affected the prices of Haiti's exports and destroyed the tenuous gains of the previous decade. Under press laws, Borno frequently imprisoned newspaper press that criticized his government.[49]

Les Cayes massacre

[edit]President Herbert Hoover had become increasingly pressured about the effects of occupying Haiti at the time and began inquiring about a withdrawal strategy.[49] By 1929, Haitians had grown angered with the Borno-Russell government and American occupation, with demands for direct elections increasing.[49] In early December 1929, protests against the American occupation began at the Service Technique de l’Agriculture et de l’Enseignement Professionnel's main school.[49] On December 6, 1929, about 1,500 Haitians peacefully protesting local economic conditions in Les Cayes were fired upon by US Marines, with the massacre resulting in 12 to 22 Haitians dead and 51 injured.[5][49][50][53][63] The massacre resulted in international outrage, with President Hoover calling on Congress to investigate conditions in Haiti the following day.[49][64]

Forbes Commission, Borno's resignation

[edit]President Hoover would later appoint two commissions, including one headed by a former US governor of the Philippines William Cameron Forbes.[52]: 232–233 [5] The commission arrived in Haiti on February 28, 1930, with President Hoover demanding the commission to determine "when and how we are to withdraw from Haiti" and "what we shall do in the meantime".[49] The Forbes Commission praised the material improvements that the US administration had achieved, but it criticized the continued exclusion of Haitian nationals from positions of real authority in the government and the gendarmerie. In more general terms, the commission asserted that "the social forces that created [instability] still remain – poverty, ignorance, and the lack of a tradition or desire for orderly free government."[65][66] The commission concluded that occupation of Haiti was a failure and that the United States did not "understand the social problems of Haiti".[50]

With increased calls for direct elections, American officials feared violence if demands were not met.[49] An agreement was made that resulted with President Borno's resignation and the establishment of Haitian banker Louis Eugène Roy as an interim president.[49] In the agreement proposed by the Forbes Commission, Roy would be elected by Congress to serve as president until a direct election for Congress was held, which is when Roy would resign.[49] American officials said that if Congress were to refuse, Roy would be installed as president forcibly.[49]

Vincent presidency

[edit]Under orders to not interfere with elections, the United States observed elections on October 14, 1930, that resulted with Haitian nationalist candidates being elected.[49] Sténio Vincent was elected President of Haiti by the Congress of Haiti in November 1930.[49] The new nationalist government had a tense relationship with American officials.[49] By the end of 1930, Haitians were being trained by Americans for administration roles of their own nation.[49] When additional American commissions began to arrive in Haiti, popular unrest broke out and President Vincent reached a secret agreement to ease tensions with the United States in exchange to grant more power to American officials to enact their "Haitianization" policies.[49]

Franklin D. Roosevelt, who as Assistant Secretary of the Navy said he was responsible for drafting the 1918 constitution,[49] was a proponent of the "Good Neighbor policy" for the US role in the Caribbean and Latin America.[12] The United States and Haiti agreed on August 7, 1933, to end the occupation.[49] On a visit to Cap-Haïtien in July 1934, Roosevelt reaffirmed the August 1933 disengagement agreement. The last contingent of US Marines departed on August 15, 1934, after a formal transfer of authority to the Garde.[67] The US retained influence on Haiti's external finances until 1947, as per the 1919 treaty that required an American financial advisor through the life of Haiti's acquired loan.[49][68]

Effects

[edit]Economy

[edit]The occupation was costly for the Haitian government; American advisors collected about 5% of Haiti's revenue while the 1915 treaty with the United States limited Haiti's income, resulting with fewer jobs for the government to assign.[7][49] Numerous agricultural changes included the introduction of sisal. Sugarcane and cotton became significant exports, boosting prosperity.[69] However, efforts to develop commercial agriculture produced limited results while American agricultural businesses removed the property from thousands of Haitian peasants to produce bananas, sisal and rubber for export, resulting with lower domestic food production.[15][62]

Haitian traditionalists, based in rural areas, were highly resistant to US-backed changes, while the urban elites, typically mixed-race, welcomed the growing economy, but wanted more political control.[45][49] Following the end of the occupation in 1934, under the Presidency of Sténio Vincent (1930–1941),[45][70] debts were still outstanding and the US financial advisor-general receiver handled the budget until 1941 when three American and three Haitian directors headed by an American manager assumed the role.[45][49] Haiti's loan debt to the United States was about twenty percent of the nation's annual revenue.[49]

Formal American influence on Haiti's economy would conclude in 1947.[68] The United Nations and the United States Department of State would report at the time that Haitian rural peasants, who comprised 90% of the nation's population, lived "close to starvation level".[7][9]

Infrastructure

[edit]The occupation improved some of Haiti's infrastructure and centralized power in Port-au-Prince, though much of the funds collected by the United States was not used to modernize Haiti.[12][48][45] Corvée forced labor of Haitians, that was enforced by the US-operated gendarmerie, was used for infrastructure projects, particularly for road building. Forced labor would ultimately result in the deaths of hundreds to thousands of Haitians.[5] Infrastructure improvements included 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi) of roads being made usable, 189 bridges built, the rehabilitation of irrigation canals, the construction of hospitals, schools, and public buildings, and drinking water was brought to the main cities. Port-au-Prince became the first Caribbean city to have a phone service with automatic dialing. Agricultural education was organized, with a central school of agriculture and 69 farms in the country.[61][18]

The majority of Haitians believed that the public works projects enforced by the US Marines were unsatisfactory.[45] American officers who controlled Haiti at the time spent more on their own salaries than on the public health budget for two million Haitians.[7] A 1949 report by the United States Department of State wrote that irrigation systems that were recently constructed were "not in good condition".[9]

Education

[edit]The United States redesigned the education system. It dismantled the liberal arts education which the Haitians had inherited (and adapted) from the French system.[71] With the Service Technique de l’Agriculture et de l’Enseignement Professionnel, Americans emphasized agricultural and vocational training, similar to its industrial education for minorities and immigrants in the United States.[49][71] Dr. Robert Russa Moton was tasked with assessing the Service Technique, concluding that though the objectives were admirable, performance was not satisfactory and criticized the large amount of funding it received compared to average Haitian public schools, which were in poor condition.[49]

Elite Haitians despised the system, believing it was discriminatory against their people.[49][71] The mulatto elite also feared the creation of an educated middle class that would potentially lead to the loss of their influence.[49]

Human rights abuses

[edit]

The United States Marines ruled Haiti as a military regime using a constant state of martial law, operating the newly created Haitian gendarmerie to suppress Haitians who opposed occupation.[11][20] Between 1915 and 1930, Haitians represented only about 35–40% of officers in the gendarmes.[49] During the occupation of Haiti by the United States, human rights abuses were committed against the native Haitian population.[11][12] Such actions involved censorship, concentration camps, forced labor, racial segregation, religious persecution of Haitian Vodou practitioners and torture.[11][12][5]

Overall, American troops and the Haitian gendarmerie killed several thousand Haitian civilians during the rebellions between 1915 and 1920, though the exact death toll is unknown.[7][5] During Senate hearings in 1921, the commandant of the Marine Corps reported that, in the 20 months of active unrest, 2,250 Haitian rebels had been killed. However, in a report to the Secretary of the Navy, he reported the death toll as being 3,250.[72] According to Haitian American academic Michel-Rolph Trouillot, about 5,500 Haitians died in labor camps alone.[5] Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, estimated that in total, including rebel combatants and civilians, at least 15,000 Haitians were killed throughout the occupation.[5] According to Paul Farmer, the higher estimates are not supported by most historians outside Haiti.[4]

American troops also performed union-busting actions, often for American businesses like the Haitian American Sugar Company, the Haitian American Development Corporation and National City Bank of New York.[11][20]

Executions and killings

[edit]

Under American occupation, extrajudicial executions were committed against Haitians.[7] During the second Caco war of 1918–1919, many Caco prisoners were summarily executed by Marines and the gendarmerie on orders from their superiors.[5] On June 4, 1916, Marines executed Caco General Mizrael Codio and ten others captured in Fonds-Verrettes.[5] In Hinche in January 1919, Captain Ernest Lavoie of the gendarmerie, a former United States Marine, allegedly ordered the killing of nineteen Caco rebels according to American officers, though no charges were placed due to no physical evidence being presented.[5] During the investigation of two marines accused of illegally executing Haitians, the attorney of the soldiers minimized their actions, saying that such killings were common, prompting larger investigations into the matter.[48]

One controversial event occurred when in an attempt to discourage rebel support from the Haitian population, the US troops took a photograph of Charlemagne Péralte's body tied to a door following his assassination in 1919, and distributed it in the country.[11][73]: 218 However, it had the opposite effect, with the image's resemblance to a crucifixion making it an icon of the resistance and establishing Péralte as a martyr.[74]

Mass killings of civilians were allegedly committed by United States Marines and their Haitian gendarmerie subordinates.[5] According to Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, such killings involved rape, lynchings, summary executions, burning villages and deaths by burning. Internal documents of the United States Army justified the killing of women and children, describing them as "auxiliaries" of rebels. A private memorandum of the Secretary of the Navy criticized "indiscriminate killings against natives". American officers responsible for acts of violence were given names in Creole such as "Linx" for Commandant Freeman Lang and "Ouiliyanm" for Sergeant Dorcas Lee Williams. According to American journalist H. J. Seligman, Marines would practice "bumping off Gooks", describing the shooting of civilians in a similar manner as killing for sport.[5]

Beginning in 1919, American troops began attacking rural villages.[5] In November 1919, villagers in Thomazeau hiding in a nearby forest sent a letter – the only surviving testament of the event – to a French priest asking for protection.[5] In the letter, survivors wrote that at least two American planes bombed and shot at two villages, killing half of the population, including men, women, children and the elderly.[5] On December 5, 1919, American planes bombed Les Cayes in a possible act of intimidation.[5] American pilots were investigated for their actions, though none were condemned.[5] These actions were described by anthropologist Jean-Philippe Belleau as possibly "the first ever carried out by air on civilian populations".[5]

Forced labor

[edit]A corvée policy of forced labor was enacted upon Haitians, enforced by the US-operated Haitian gendarmerie in the interest of improving economic conditions to fulfill foreign debts – including payments to the United States – and to improve the nation's infrastructure.[11][12][16] The corvée system was found in Haiti's rural code by Major Smedley D. Butler, who testified that forced labor cut the cost of 1 mile (1.6 km) of road construction from $51,000 per mile to $205 per mile.[48]

The corvée resulted in the deaths of hundreds to thousands of Haitians. Haitians were tied together in rope and those fleeing labor projects were often shot.[7] According to Haitian American academic Michel-Rolph Trouillot, about 5,500 Haitians died in labor camps.[5] In addition, Roger Gaillard writes that some Haitians were killed fleeing the camps or if they did not work satisfactorily.[5] Many of the deaths and killings attributed to forced labor occurred during the extensive construction of roads in Haiti.[5] In some instances, Haitians were forced to work on projects without pay and while shackled to chains.[11] The corvée system's treatment of Haitians has been compared to the system of bondage labor enforced upon black Americans during the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War.[11]

Racism

[edit]Many of those tasked with the occupation of Haiti espoused racist beliefs.[7] The first Marine commander ashore assigned was Colonel Littleton Waller, who had a history of racism against mulattos, describing them as "real nigger ... real nigs beneath the surface".[48][75] Wilson's Secretary of State Robert Lansing also held racist beliefs, writing at the time that "the African race are devoid of any capacity for political organization".[7][75] The United States introduced Jim Crow laws to Haiti with racist attitudes towards the Haitian people by the American occupation forces that were blatant and widespread.[7][50][76] Many of the Marines chosen to occupy Haiti were from the Southern United States, specifically Alabama and Louisiana, resulting in increased racial tensions.[5][50] Racism has been recognized as a factor leading to increased violence by American troops against Haitians. One general described Haitians as "niggers who pretend to speak French".[5]

Initially, officers and the elites intermingled at social gatherings and clubs. Such gatherings were minimized when families of American forces began arriving.[76] Relations degraded rapidly upon departure of officers for World War I.[76] The Haitian elite found the American junior and non-commissioned officers to be ignorant and uneducated.[76] There were numerous reports of remaining Marines drinking to excess, fighting, and sexually assaulting women.[76] The situation was so bad that Marine general John A. Lejeune, based in Washington, D.C., banned the sale of alcohol to any military personnel.[76]

The Americans inhabited neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince in high-quality housing. This neighborhood was called the "millionaires' row".[77] Hans Schmidt recounted a navy officer's opinion on the matter of segregation: "I can't see why they wouldn't have a better time with their crowd, just as I do with mine."[78] American racial intolerance provoked indignation and resentment – and eventually a racial pride that was reflected in the work of a new generation of Haitian historians, ethnologists, writers, artists, and others. Many of these later became active in politics and government. The elite Haitians, mostly mixed-race with higher levels of education and capital, continued to dominate the country's bureaucracy and to strengthen its role in national affairs.[citation needed]

Colorism, which had existed since French colonization, had also become prevalent once more under American occupation and racial segregation became common.[11] All three rulers during the occupation came from the country's mixed-race elite.[79] At the same time, many in the growing black professional classes departed from the traditional veneration of Haiti's French cultural heritage and emphasized the nation's African roots.[79] Among these were ethnologist Jean Price-Mars and François Duvalier, editor of the journal Les Griots (the title referred to traditional African oral historians, the storytellers) and future totalitarian president of Haiti. The racism and violence that occurred during the United States occupation of Haiti, inspired black nationalism among Haitians and left a powerful impression on the young Duvalier.[50]

Torture

[edit]The torture of Haitian rebels or those suspected of rebelling against the United States was common among occupying Marines. Some methods of torture included the use of water cure, hanging prisoners by their genitals and ceps, which involved pushing both sides of the tibia with the butts of two guns.[5]

Analysis

[edit]20th century

[edit]Haitian writers and public figures also responded to the occupation. For example, a minister of public education, Dantès Bellegarde raised issues with the events in his book, La Résistance Haïtienne (l'Occupation Américaine d'Haïti). Bellegarde outlines the contradictions of the occupation with the realities. He accused President Wilson of writing the new Haitian Constitution to benefit the Americans, and wrote that Wilson's main purpose was to remove the previous Haitian clause that stated foreigners could not own land in the country. The original clause was designed to protect Haiti's independence from foreign powers.[80] With the clause removed, Americans (including whites and other foreigners) could now own land. Furthermore, Bellegarde discusses the powerlessness of Haitian officials in the eyes of the Occupation because nothing could be done without the consent of the Americans. However, the main issue that Bellegarde articulates is that the Americans tried to change the education system of Haiti from one that was French based to that of the Americans. Even though Bellegarde was resistant he had a plan to build a university in Haiti that was based on the American system. He wanted a university with various schools of science, business, art, medicine, law, agriculture, and languages all connected by a common area and library. However, that dream was never realized because of the new direction the Haitian government was forced to take.

Jean Price-Mars[81] associated the reasons behind the occupation to the division between the Haitian elite and the poorer people of the country. He noted that the groups were divided over the practice of Haitian Vodou, with the implication that the elites did not recognize Vodou because they connected it to an evil practice.[82]

21st century

[edit]Pezullo writes in his 2006 book Plunging Into Haiti: Clinton, Aristide, and the Defeat of Diplomacy that the racism similar to Jim Crow laws in the United States inspired black nationalism within Haiti and ignited future support for Haitian dictator François Duvalier.[50]

In a 2013 article by Peter James Hudson published in Radical History Review, Hudson wrote:[20]

Ostensibly initiated on humane grounds, the occupation had not fulfilled any of its stated goals of building infrastructure, expanding education, or providing internal or regional stability. Repressive violence emerged as its only purpose and logic.

Hudson further stated that the motives of American businessmen to become involved in Haiti were due to racial capitalism motivated by white supremacy.[20]

According to a 2020 study which contrasts the American occupations of both Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the United States had a longer and more domineering occupation of Haiti because of perceived racial differences between the two populations. Dominican elites articulated a European–Spanish identity – in contrast to Haitian blackness – which led US policymakers to accept leaving the territory in the population's hands.[83]

See also

[edit]- History of the Dominican Republic

- History of Haiti

- Banana Wars

- Battle of Fort Dipitie

- Battle of Fort Rivière

- Dominican Republic–United States relations

- United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–1924)

- Haiti during World War I

- Haiti–United States relations

- Foreign interventions by the United States

- Foreign policy of the United States

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Latin America–United States relations

- United States involvement in regime change

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Clodfelter (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015. p. 378.

- ^ Hans Schmidt, The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), p. 103; and “Americans Killed in Action,” American War Library, http://www.americanwarlibrary.com/allwars.htm Archived February 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Schmidt cites 146 Marine deaths in Haiti; and the American War Library cites 144 Marines killed in action in the Dominican Republic.

- ^ Hans Schmidt (1971). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. Rutgers University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780813522036.

- ^ a b Farmer, Paul (2003). The Uses of Haiti. Common Courage Press. p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Belleau, Jean-Philippe (January 25, 2016). "Massacres perpetrated in the 20th Century in Haiti". Sciences Po. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Schmidt, Hans (March 12, 1995). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2203-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Gebrekidan, Selam; Apuzzo, Matt; Porter, Catherine; Méheut, Constant (May 20, 2022). "Invade Haiti, Wall Street Urged. The U.S. Obliged". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ McLellan, James May (2010). Colonialism and Science: Saint Domingue and the Old Regime (reprint ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-226-51467-3. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

[...] French Saint Domingue at its height in the 1780s had become the single richest and most productive colony in the world.

- ^ a b c Agricultural Progress in Haiti: Summary Report, 1944–1949, of the Service Coopératif Inter-américain de Production Agricole (SCIPA) and the IIAA Food Supply Mission to Haiti. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State. July 1949. pp. 1–34.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bauduy, Jennifer (2015). "The 1915 U.S. Invasion of Haiti: Examining a Treaty of Occupation" (PDF). Social Education. 79 (5): 244–249.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Alcenat, Westenly. "The Case for Haitian Reparations". Jacobin. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "U.S. Invasion and Occupation of Haiti, 1915–34". United States Department of State. July 13, 2007. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Home Again from Haiti". The New York Times. May 17, 1891. p. 5.

- ^ a b c Léger, Jacques Nicolas (1907). "Chapter XXII". Haiti, her history and her detractors. New York; Washington: The Neale Pub. Co. pp. 245–247. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hubert, Giles A. (January 1947). "War and the Trade Orientation of Haiti". Southern Economic Journal. 13 (3): 276–284. doi:10.2307/1053341. JSTOR 1053341.

- ^ a b Paul Farmer, The Uses of Haiti (Common Courage Press: 1994)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Schmidt, Hans (1995). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. Rutgers University Press. pp. 43–54.

- ^ a b Occupation of Haiti, 1915–34 Archived November 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, US Department of State

- ^ a b Schmidt, 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Hudson, Peter James (2013). "The National City Bank of New York and Haiti, 1909–1922". Radical History Review. Winter 2013 (115). Duke University Press: 91–107. doi:10.1215/01636545-1724733.

- ^ a b c d e Milieu, Richard (1976). "Protectorates: The U.S. Occupation of Haiti and the Dominican Republic" (PDF). United States Marine Corps. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Hurry Election Of Simon In Haiti; Followers Fear Delay May Cause Disorders And Invite Intervention From United States" Archived March 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, December 8, 1908

- ^ "Simon Elected President; Following Action by Haitian Congress, He Is Recognized By The United States" Archived March 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 18, 1908

- ^ "Leconte in Haiti's Capital; Revolutionary Leader Takes Possession of National Palace" (PDF). The New York Times. August 8, 1911. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Hayes, Carlton H.; Edward M. Sait (December 1912). "Record of Political Events". Political Science Quarterly. 27 (4): 752. doi:10.2307/2141264. JSTOR 2141264.

- ^ Kaplan, U.S. Imperialism in Latin America, p. 61.

- ^ Heinl 1996, p. 791.

- ^ a b c Douglas, Paul H. from Occupied Haiti, ed. Emily Greene Balch (New York, 1972), 15–52 reprinted in: Money Doctors, Foreign Debts, and Economic Reforms in Latin America. Wilmington, DE: edited by Paul W. Drake, 1994.

- ^ a b c d Apuzzo, Matt; Méheut, Constant; Gebrekidan, Selam; Porter, Catherine (May 20, 2022). "How a French Bank Captured Haiti". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Gamio, Lazaro; Méheut, Constant; Porter, Catherine; Gebrekidan, Selam; McCann, Allison; Apuzzo, Matt (May 20, 2022). "Haiti's Lost Billions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Hudson, Peter James (2017). Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean. University of Chicago Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780226459257.

- ^ Vanderlip, Frank A. (1909). Frank A. Vanderlip to James Stillman, April 8, 1909.

- ^ Plummer, Brenda Gayle (1988). Haiti and the Great Powers, 1902–1915. Louisiana State University Press. p. 169.

- ^ a b Johnson 2019, p. 66.

- ^ Bryan, William Jennings (1914). William Jennings Bryan to American Consul, Cap Haitien, July 19, 1914. United States Department of State.

- ^ Bytheway, Simon James; Metzler, Mark (2016). Central Banks and Gold: How Tokyo, London, and New York Shaped the Modern World. Cornell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9781501706509.

- ^ Millett, Allan Reed (1991). Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 185. ISBN 9780029215968. Archived from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ Weinstein, Segal 1984, p.28

- ^ Panton, Kenneth J. (August 23, 2022). Historical Dictionary of the United States. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-5381-2420-8.

- ^ Security Assistance, U.S. and International Historical Perspectives: Proceedings of the Combat Studies Institute 2006 Military History Symposium. Government Printing Office. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-16-087349-2.

- ^ "Haiti's Tragic History": Review of Laurent Dubois, Haiti: The Aftershocks of History Archived October 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, January 1, 2012

- ^ Weston 1972, p. 217.

- ^ Pamphile, Léon Dénius (2008). Clash of Cultures :America's Educational Strategies in Occupied Haiti, 1915–1934. Lanham: University Press of America. p. 22. ISBN 9780761839927.

- ^ Renda, Mary (2001). Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism 1915–1940. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-8078-2628-7.

- ^ a b c d e f "Haiti" Archived May 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Weinstein, Segal 1984, p. 29.

- ^ Plunging Into Haiti: Clinton, Aristide, and the Defeat of Diplomacy, p. 78, at Google Books

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bunce, Peter L. (2003). Foundations on Sand: An Analysis of the First US Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. University of Kansas.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj Munro, Dana G. (1969). "The American Withdrawal from Haiti, 1929–1934". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 49 (1): 1–26. doi:10.2307/2511314. JSTOR 2511314.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pezzullo, Ralph (2006). Plunging Into Haiti: Clinton, Aristide, and the Defeat of Diplomacy. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 77–100. ISBN 9781604735345.

- ^ Sannon, Horace Pauleus (1933) [1920]. Histoire de Toussaint-Louverture. Port-Au-Prince: Impr. A.A. Héraux. p. 142. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Musicant, I, The Banana Wars, 1990, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., ISBN 0025882104

- ^ a b c U.S. Haiti Rebellion 1918 Archived June 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, On War

- ^ Roosevelt asserted his authorship of the Haitian Constitution in several speeches during his 1920 campaign for Vice President – which was at best a politically awkward overstatement and caused some controversy in the campaign. (Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Crisis of the Old Order, 364, citing 1920 Roosevelt Papers for speeches in Spokane, San Francisco, and Centralia.)

- ^ "SAYS AMERICA HAS 12 LEAGUE VOTES; Roosevelt Declares He Himself Had Two Until Last Week, Referring to Minor Republics" (PDF). The New York Times. August 19, 1920. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ James W. Loewen, "Lies My Teacher Told Me" (New York: The New Press, 2018), p. 18

- ^ A., Renda, Mary (2001). Taking Haiti : military occupation and the culture of U.S. imperialism, 1915–1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807826287. OCLC 56356679.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Haiti, Haitians, and Black America". H Net. September 2004. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2010..

- ^ Brandon Byrd, ""To Start Something to Help These People:" African American Women and the Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934"[permanent dead link], The Journal of Haitian Studies, Volume 21 No. 2 (2015), accessed February 2, 2016

- ^ Pietrusza, David (2008). 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents. Basic Books. p. 133.

- ^ a b Heinl 1996, pp. 454–455.

- ^ a b Woodling, Bridget; Moseley-Williams, Richard (2004). Needed but Unwanted: Haitian Immigrants and Their Descendants in the Dominican Republic. London: Catholic Institute for International Relations. p. 24.

- ^ Danticat, Edwidge (July 28, 2015). "The Long Legacy of Occupation in Haiti". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "1929: Cayes Massacre". Arizona Daily Star. April 22, 2021. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Occupation of Haiti 1915–34" Archived February 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Globalsecurity.org.

- ^ Forbes, William Cameron; et al. (Forbes Commission) (1930). Report of the President's Commission for the Study and Review of Conditions in the Republic of Haiti: March 26, 1930. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 19. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ p 223 – Benjamin Beede (1994). The War of 1898 and U.S. Interventions, 1898–1934: An Encyclopedia (May 1, 1994 ed.). Routledge; 1 edition. pp. 784. ISBN 0-8240-5624-8.

The Haitian and US governments reached a mutually satisfactory agreement in the Executive Accord of August 7, 1933, and on August 15, the last marines departed. - ^ a b Schmidt, Hans. The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. (232)

- ^ Henl, pp. 454–455.

- ^ Angulo, A. J. (2010). "Education During the American Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934". Historical Studies in Education. 22 (2): 1–17. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c Schmidt, p. 183.

- ^ Hans Schmidt (1971). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. Rutgers University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780813522036.

- ^ Musicant, I, The Banana Wars, 1990, New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., ISBN 0025882104

- ^ "An Iconic Image of Haitian Liberty". The New Yorker. July 28, 2015. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Chomsky, Noam (2015). Turning the Tide: U.S. Intervention in Central America and the Struggle for Peace. Haymarket Books. p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e f Pamphile, Léon Dénius (2008). Clash of Cultures: America's Educational Strategies in Occupied Haiti, 1915–1934. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. p. 177.

- ^ Schmidt 1995, p.152.

- ^ Schmidt 1995, p.137-38.

- ^ a b Schmidt, p. 23.

- ^ "Dantès Bellegarde". December 13, 2003. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "Jean Price-Mars" Archived April 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Lehman Center, City University of New York

- ^ Price-Mars, Jean (1983). So Spoke The Uncle. Washington, D.C.: Three Continents Press. pp. 1–221. ISBN 0894103903.

- ^ Pampinella, Stephen (2020). ""The Way of Progress and Civilization": Racial Hierarchy and US State Building in Haiti and the Dominican Republic (1915–1922)". Journal of Global Security Studies. 6 (3). doi:10.1093/jogss/ogaa050. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Heinl, Robert (1996). Written in Blood: The History of the Haitian People. Lantham, MD: University Press of America.

- Johnson, Wray R. (2019). Biplanes at War: US Marine Corps Aviation in the Small Wars Era, 1915–1934. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813177069. - Total pages: 440

- Schmidt, Hans (1995). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Weinstein, Brian; Segal, Aaron (1984). Haiti: Political Failures, Cultural Successes (February 15, 1984 ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 0-275-91291-4.

- Weston, Rubin Francis (1972). Racism in U.S. Imperialism: The Influence of Racial Assumptions on American Foreign Policy, 1893–1946. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Boot, Max. The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York, Basic Books: 2002. ISBN 0-465-00721-X

- Dalleo, Raphael (2016). American Imperialism's Undead: The Occupation of Haiti and the Rise of Caribbean Anticolonialism. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-3894-3.

- Gebrekidan, Selam; Apuzzo, Matt; Porter, Catherine; Méheut, Constant (May 20, 2022). "Invade Haiti, Wall Street Urged. The U.S. Obliged". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- Harper's Magazine advertisement: Why Should You Worry About Haiti? by the Haiti-Santo Domingo Independence Society

- Hudson, Peter (2017). Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-2264-5911-0.

- Marvin, George (February 1916). "Assassination And Intervention in Haiti: Why The United States Government Landed Marines On The Island And Why It Keeps Them There". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXXI: 404–410. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- Renda, Mary A. (2001). Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4938-3.

- Schmidt, Hans (1995). United States occupation of Haiti (1915-1934). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2203-X.

- Spector, Robert M. "W. Cameron Forbes in Haiti: Additional Light on the Genesis of the 'Good Neighbor' Policy" Caribbean Studies (1966) 6#2 pp 28–45.

- Weston, Rubin Francis (1972). Racism in U.S. Imperialism: The Influence of Racial Assumptions on American Foreign Policy, 1893–1946. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-219-2.

Primary sources

[edit]- Forbes, William Cameron. Report of the President's Commission for the Study and Review of Conditions in the Republic of Haiti: March 26, 1930 (US Government Printing Office, 1930) online

- United States occupation of Haiti

- American imperialism

- Conflicts in 1915

- Republic of Haiti (1859–1957)

- Invasions of Haiti

- Wars involving Haiti

- Wars involving the United States

- Military history of Haiti

- 20th-century military history of the United States

- Banana Wars

- 1915 in Haiti

- 1915 in the United States

- American military occupations

- United States Marine Corps in the 20th century

- 1915 in international relations

- Haiti–United States military relations

- United States involvement in regime change

- Presidency of Woodrow Wilson

- Presidency of Warren G. Harding

- Presidency of Calvin Coolidge

- Presidency of Herbert Hoover

- Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Invasions by the United States

- Citigroup