Attar of Nishapur

Attar of Nishapur | |

|---|---|

Bust of Attar at his mausoleum | |

| Mystic Poet | |

| Born | c. 1145[1] Nishapur, Seljuk Empire |

| Died | c. 1221 (aged 75–76) Nishapur, Khwarezmian Empire |

| Resting place | Mausoleum of Attar, Nishapur, Iran |

| Venerated in | Traditional Islam, and especially by Sufis[2] |

| Influences | Ferdowsi, Sanai, Khwaja Abdullah Ansari, Mansur Al-Hallaj, Abu-Sa'id Abul-Khayr, Bayazid Bastami |

| Influenced | Rumi, Hazrat Ishaan, Sayyid Alauddin Atar, Hafez, Jami, Ali-Shir Nava'i and many other later Sufi Poets |

Tradition or genre | Mystic poetry |

| Major works | Memorial of the Saints The Conference of the Birds |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

Faridoldin Abu Hamed Mohammad Attar Neyshaburi (c. 1145 – c. 1221; Persian: ابوحمید بن ابوبکر ابراهیم), better known by his pen-names Faridoldin (فریدالدین) and ʿAttar of Nishapur (عطار نیشاپوری, Attar means apothecary), was an Iranian poet, theoretician of Sufism, and hagiographer from Nishapur who had an immense and lasting influence on Persian poetry and Sufism. He wrote a collection of lyrical poems and number of long poems in the philosophical tradition of Islamic mysticism, as well as a prose work with biographies and sayings of famous Muslim mystics.[3] The Conference of the Birds, Book of the Divine, and Memorial of the Saints are among his best known works.

Biography

[edit]Information about Attar's life is scarce and has been mythologised over the centuries. However, Attar was born to a Persian[4][5][6] family and he practised the profession of pharmacist and personally attended to a very large number of customers.[7] He is mentioned by only two of his contemporaries, `Awfi and Tusi. However, all sources confirm that he was from Nishapur, a major city of medieval Khorasan (now located in the northeast of Iran), and according to `Awfi, he was a poet of the Seljuq period.

According to Reinert: It seems that he was not well known as a poet in his own lifetime, except at his home town, and his greatness as a mystic, a poet, and a master of narrative was not discovered until the 15th century.[4] At the same time, the mystic Persian poet Rumi has mentioned: "Attar was the spirit, Sanai his eyes twain, And in time thereafter, Came we in their train"[8] and mentions in another poem:

Attar travelled through all the seven cities of love

While I am only at the bend of the first alley..[9]

Attar was probably the son of a prosperous chemist, receiving an excellent education in various fields. While his works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practised the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers.[4] The people he helped in the pharmacy used to confide their troubles in Attar and this affected him deeply. Eventually, he abandoned his pharmacy store and travelled widely - to Baghdad, Basra, Kufa, Mecca, Medina, Damascus, Khwarizm, Turkistan, and India, meeting with Sufi Shaykhs - and returned promoting Sufi ideas.[10] Attar was a Sunni Muslim.[11]

From childhood onward Attar, encouraged by his father, was interested in the Sufis and their sayings and way of life, and regarded their saints as his spiritual guides.[12] At the age of 78, Attar died a violent death in the massacre which the Mongols inflicted on Nishapur in April 1221.[4] Today, his mausoleum is located in Nishapur. It was built by Ali-Shir Nava'i in the 16th century and later underwent a total renovation during the rule of Reza Shah in 1940.

Teachings

[edit]

The thoughts depicted in Attar's works reflect the whole evolution of the Sufi movement. The starting point is the idea that the body-bound soul's awaited release and return to its source in the other world can be experienced during the present life in mystic union attainable through inward purification.[13] In explaining his thoughts, Attar uses material not only from specifically Sufi sources but also from older ascetic legacies. Although his heroes are for the most part Sufis and ascetics, he also introduces stories from historical chronicles, collections of anecdotes, and all types of high-esteemed literature.[4] His talent for perception of deeper meanings behind outward appearances enables him to turn details of everyday life into illustrations of his thoughts. The idiosyncrasy of Attar's presentations invalidates his works as sources for study of the historical persons whom he introduces. As sources on the hagiology and phenomenology of Sufism, however, his works have immense value.

Judging from Attar's writings, he approached the available Aristotelian heritage with scepticism and dislike.[14][15] He did not seem to want to reveal the secrets of nature. This is particularly remarkable in the case of medicine, which fell well within the scope of his professional expertise as pharmacist. He obviously had no motive for sharing his expert knowledge in the manner customary among court panegyrists, whose type of poetry he despised and never practised. Such knowledge is only brought into his works in contexts where the theme of a story touches on a branch of the natural sciences.

According to Edward G. Browne, Attar as well as Rumi and Sana'i, were Sunni as evident from the fact that their poetry abounds with praise for the first two caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar ibn al-Khattāb - who are detested by Shia mysticism.[11] According to Annemarie Schimmel, the tendency among Shia authors to include leading mystical poets such as Rumi and Attar among their own ranks, became stronger after the introduction of Twelver Shia as the state religion in the Safavid Empire in 1501.[16]

Poetry

[edit]Attar's most famous poem by far is his Conference of the Birds (Mantiq al-tayr). Like many of his other poems, it is in the mathnawi genre of rhyming couplets. While the mathnawi genre of poetry may use a variety of different metres, Attar adopted a particular meter, that was later imitated by Rumi in his famous Mathnawi-yi Ma’nawi, which then became the mathnawi metre par excellence. The first recorded use of this metre for a mathnawi poem took place at the Nizari Ismaili fortress of Girdkuh between 1131 and 1139. It likely set the stage for later poetry in this style by mystics such as Attar and Rumi.[17]

In the introductions of Mukhtār-Nāma (مختارنامه) and Khusraw-Nāma (خسرونامه), Attar lists the titles of further products of his pen:

- Dīwān (دیوان)

- Asrār-Nāma (اسرارنامه)

- Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr (منطقالطیر), also known as Maqāmāt-uṭ-Ṭuyūr (مقاماتالطیور)

- Muṣībat-Nāma (مصیبتنامه)

- Ilāhī-Nāma (الهینامه)

- Jawāhir-Nāma (جواهرنامه)

- Šarḥ al-Qalb[18] (شرحالقلب)

He also states, in the introduction of the Mukhtār-Nāma, that he destroyed the Jawāhir-Nāma' and the Šarḥ al-Qalb with his own hand.

Although the contemporary sources confirm only Attar's authorship of the Dīwān and the Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr, there are no grounds for doubting the authenticity of the Mukhtār-Nāma and Khusraw-Nāma and their prefaces.[4] One work is missing from these lists, namely the Tadhkirat-ul-Awliyā, which was probably omitted because it is a prose work; its attribution to Attar is scarcely open to question. In its introduction Attar mentions three other works of his, including one entitled Šarḥ al-Qalb, presumably the same that he destroyed. The nature of the other two, entitled Kašf al-Asrār (کشفالاسرار) and Maʿrifat al-Nafs (معرفتالنفس), remains unknown.[19]

Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr

[edit]In the poem, the birds of the world gather to decide who is to be their sovereign, as they have none. The hoopoe, the wisest of them all, suggests that they should find the legendary Simorgh. The hoopoe leads the birds, each of whom represents a human fault which prevents human kind from attaining enlightenment.

The hoopoe tells the birds that they have to cross seven valleys in order to reach the abode of Simorgh. These valleys are as follows:[20][21]

- 1. Valley of the Quest, where the Wayfarer begins by casting aside all dogma, belief, and unbelief.

- 2. Valley of Love, where reason is abandoned for the sake of love.

- 3. Valley of Knowledge, where worldly knowledge becomes utterly useless.

- 4. Valley of Detachment, where all desires and attachments to the world are given up. Here, what is assumed to be “reality” vanishes.

- 5. Valley of Unity, where the Wayfarer realises that everything is connected and that the Beloved is beyond everything, including harmony, multiplicity, and eternity.

- 6. Valley of Wonderment, where, entranced by the beauty of the Beloved, the Wayfarer becomes perplexed and, steeped in awe, finds that he or she has never known or understood anything.

- 7. Valley of Poverty and Annihilation, where the self disappears into the universe and the Wayfarer becomes timeless, existing in both the past and the future.

Sholeh Wolpé writes, "When the birds hear the description of these valleys, they bow their heads in distress; some even die of fright right then and there. But despite their trepidations, they begin the great journey. On the way, many perish of thirst, heat or illness, while others fall prey to wild beasts, panic, and violence. Finally, only thirty birds make it to the abode of Simorgh. In the end, the birds learn that they themselves are the Simorgh; the name “Simorgh” in Persian means thirty (si) birds (morgh). They eventually come to understand that the majesty of that Beloved is like the sun that can be seen reflected in a mirror. Yet, whoever looks into that mirror will also behold his or her own image.[20][21]: 17–18

- If Simorgh unveils its face to you, you will find

- that all the birds, be they thirty or forty or more,

- are but the shadows cast by that unveiling.

- What shadow is ever separated from its maker?

- Do you see?

- The shadow and its maker are one and the same,

- so get over surfaces and delve into mysteries.[20][21]

Attar's masterful use of symbolism is a key, driving component of the poem. This adroit handling of symbolisms and allusions can be seen reflected in these lines:

It was in China, late one moonless night, The Simorgh first appeared to mortal sight

Beside the symbolic use of the Simorgh, the allusion to China is also very significant. According to Idries Shah, China as used here, is not the geographical China, but the symbol of mystic experience, as inferred from the Hadith (declared weak by Ibn Adee, but still used symbolically by some Sufis): "Seek knowledge; even as far as China".[5] There are many more examples of such subtle symbols and allusions throughout the Mantiq. Within the larger context of the story of the journey of the birds, Attar masterfully tells the reader many didactic short, sweet stories in captivating poetic style.

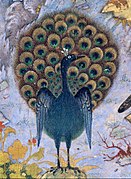

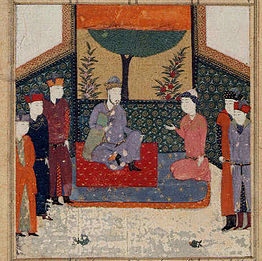

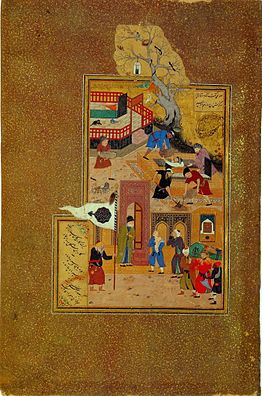

Gallery of The Conference of the Birds

[edit]Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Folio from an illustrated manuscript dated c.1600. Paintings by Habiballah of Sava (active ca. 1590–1610), in ink, opaque watercolour, gold, and silver on paper, dimensions 25,4 x 11,4 cm.[22]

Tadhkirat-ul-Awliyā

[edit]The Tadhkirat-ul-Awliyā, a hagiographic collection of Muslim saints and mystics, is Attar's only known prose work. Written and compiled throughout much of his life and published before his death, the compelling account of the execution of the mystic Mansur al-Hallaj, who had uttered the words "I am the Truth" in a state of ecstatic contemplation, is perhaps the most well known extract from the book.

Ilāhī-Nāma

[edit]The Ilāhī-Nāma (Persian: الهینامه) or Elāhī-Nāme(h) is another famous poetic work of Attar, consisting of 6500 verses. In terms of form and content, it has some similarities with Bird Parliament. The story is about a king who is confronted with the materialistic and worldly demands of his six sons. The King tries to show the temporary and senseless desires of his six sons by retelling them a large number of spiritual stories. The first son asks for the daughter of the king of the fairies, the second for the mastery of magic, the third for the cup of Jamshid, which has the property of displaying the whole world, the fourth for the water of life, the fifth for the ring of Solomon, which has control over fairies and demons, and the sixth for mastering alchemy. Each of these desires is discussed first literally, and shown to be absurd, and then it is explained how there is an esoteric interpretation of each one.[23]

Mukhtār-Nāma

[edit]Mukhtār-Nāma (Persian: مختارنامه), a wide-ranging collection of quatrains (2088 in number). In the Mokhtar-nama, a coherent group of mystical and religious subjects is outlined (search for union, sense of uniqueness, distancing from the world, annihilation, amazement, pain, awareness of death, etc.), and an equally rich group of themes typical of lyrical poetry of erotic inspiration adopted by mystical literature (the torment of love, impossible union, beauty of the loved one, stereotypes of the love story as weakness, crying, separation).[24]

Divan

[edit]

The Diwan of Attar (Persian: دیوان عطار) consists almost entirely of poems in the Ghazal ("lyric") form, as he collected his Ruba'i ("quatrains") in a separate work called the Mokhtar-nama. There are also some Qasida ("Odes"), but they amount to less than one-seventh of the Divan. His Qasidas expound upon mystical and ethical themes and moral precepts. They are sometimes modelled after Sanai. The Ghazals often seem from their outward vocabulary just to be love and wine songs with a predilection for libertine imagery, but generally imply spiritual experiences in the familiar symbolic language of classical Islamic Sufism.[4] Attar's lyrics express the same ideas that are elaborated in his epics. His lyric poetry does not significantly differ from that of his narrative poetry, and the same may be said of the rhetoric and imagery.

Legacy

[edit]Influence on Rumi

[edit]Attar is one of the most famous mystic poets of Iran. His works were the inspiration of Rumi and many other mystic poets. Attar, along with Sanai were two of the greatest influences on Rumi in his Sufi views. Rumi has mentioned both of them with the highest esteem several times in his poetry. Rumi praises Attar as follows:

Attar has roamed through the seven cities of love while we have barely turned down the first street.[25]

Descendants

[edit]Significant descendants of Attar include Sayyid Alauddin Atar and the Hazrat Ishaan. Damrel mentioned Sayyid Alauddin Atars genealogy reaching Attar, referencing Moinuddin Hadi Naqshbands, by virtue of his maternal lineage. Attar's descendants left a significant mystical influence as supreme leaders of the Naqshbandiyya in a legacy reaching the Qutb Sayyid Mir Jan.[26]

As a pharmacist

[edit]Attar was a pen-name which he took for his occupation. Attar means herbalist, druggist, perfumist or alchemist, and during his lifetime in Persia, much of medicine and drugs were based on herbs. Therefore, by profession he was similar to a modern-day town doctor and pharmacist. Further, 'Attar also refers to rose oil.

In popular culture

[edit]Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges used a summary reference to The Conference of the Birds in his short story, The Approach to Al-Mu'tasim (1936).[27] The Ubuntu Theater Project in Berkeley California premiered an adaptation of Attar's The Conference of the Birds by Sholeh Wolpe, in Oakland, California.

In an 1822 entry, the French writer François-René de Chateaubriand quoted a line, "Palaces are not built on the sea," in Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, 1768-1800. Chateaubriand probably encountered "Farid ud-Din" through the 1819 translation of Silvestre de Sacy, Le Livre des Conseils.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica

- ^ Daadbeh, Asghar and Melvin-Koushki, Matthew, “ʿAṭṭār Nīsābūrī”, in: Encyclopaedia Islamica, Editors-in-Chief: Wilferd Madelung and, Farhad Daftary

- ^ Oxford illustrated encyclopedia. Judge, Harry George., Toyne, Anthony. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. 1985–1993. p. 25. ISBN 0-19-869129-7. OCLC 11814265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g B. Reinert, "`Attar", in Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition

- ^ Ritter, H. (1986), “Attar”, Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Ed., vol. 1: 751-755. Excerpt: "ATTAR, FARID AL-DIN MUHAMMAD B. IBRAHIM.Persian mystical poet.Yahiya Emerick (5 February 2008), The Complete Idiot's Guide to Rumi Meditations, "The three most influential Persian poets of all time, Fariduddin 'Attar, Hakim Sana'i, and Jalaluddin Rumi, were all Muslims, while Persia (Iran) today is over 90 percent Shi'a Muslim", Alpha, p. 48, ISBN 9781440636448

- ^ Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār, in Encyclopædia Britannica, online edition - accessed December 2012. [1]

- ^ "Attar and The Conference of the Birds". Archived from the original on 2021-08-16.

- ^ "A. J. Arberry, "Sufism: An Account of the Mystics ", Courier Dover Publications, Nov 9, 2001. p. 141

- ^ Sholeh Wolpé, "The Conference of the Birds" W. W. Norton & Co, 2017, First edition p. 5

- ^ Iraj Bashiri, "Farid al-Din `Attar"

- ^ a b Edward G. Browne, A Literary History of Persia from the Earliest Times Until Firdawsi, 543 pp., Adamant Media Corporation, 2002, ISBN 1-4021-6045-3, ISBN 978-1-4021-6045-5 (see p.437)

- ^ Taḏkerat al-Awliyā; pp. 1,55,23 ff

- ^ F. Meier, "Der Geistmensch bei dem persischen Dichter `Attar", Eranos-Jahrbuch 13, 1945, pp. 286 ff

- ^ Muṣībat-Nāma, p. 54 ff

- ^ Asrār-Nāma, pp. 50, 794 ff

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Deciphering the Signs of God, 302 pp., SUNY Press, 1994, ISBN 0-7914-1982-7, ISBN 978-0-7914-1982-3 (see p.210)

- ^ “Persian Poetry, Sufism and Ismailism: The Testimony of Khwajah Qasim Tushtari's Recognizing God.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Series 3 29, no. 1 (2019): 17–49. https://www.academia.edu/40141803/

- ^ quoted in H. Ritter, "Philologika X," pp. 147-53

- ^ Ritter, "Philologika XIV," p. 63

- ^ a b c ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn (2017). The conference of the birds. Translated by Wolpé, Sholeh (First ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393292183. OCLC 951070853.

- ^ a b c The Conference of the Birds by Attar, edited and translated by Sholeh Wolpé, W. W. Norton & Co 2017 ISBN 978-0-393-29218-3 [verification needed]

- ^ "The Concourse of the Birds", Folio 11r from a Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), The Met

- ^ Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār (1976). The 'Ilāhī-nāma [Book of God]. UNESCO collection of representative works: Persian heritage series; [no. 29]. Translated by John Andrew Boyle. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719006635. Foreword by Annemarie Schimmel. The 'Ilāhī-nāma is a 12th century Persian poem. An incompletely edited version is publicly accessible

- ^ Daniela Meneghini, "MOḴTĀR-NĀMA"[dead link]

- ^ Fodor's Iran (1979) by Richard Moore and Peter Sheldon, p. 277

- ^ Damrel in Forgotten Grace, p. 21

- ^ Alazraki, Jaime (1987). Critical Essays on Jorge Luis Borges. G. K. Hall & Co. p. 43. ISBN 0-8161-8829-7.

- ^ Chateaubriand, François-René de; Muhlstein, Anka; Andriesse, Alex (2018). Memoires from beyond the grave. Vol. 1: Memoires from beyond the grave: 1768 - 1800 / François-René de Chateaubriand. Introduction by Anka Muhlstein; Translated from the French by Alex Andriesse. Vol. 1. New York: New York Review of Books. pp. 340, endnote 10, 540. ISBN 978-1-68137-129-0.

Sources

[edit]- Sholeh Wolpé. The Conference of the Birds. 2017 ISBN 978-0-393-29218-3

- E.G. Browne. Literary History of Persia. 1998. ISBN 0-7007-0406-X.

- Jan Rypka, History of Iranian Literature. Reidel Publishing Company. 1968 OCLC 460598. ISBN 90-277-0143-1

- R. M. Chopra, 2014, " Great Poets of Classical Persian ", Sparrow Publication, Kolkata (ISBN 978-81-89140-75-5)

External links

[edit]- Attar, the Sufi, the poet, World Literature Today

- The Conference of the Birds, translated by Sholeh Wolpe

- Bird Parliament Fitzgerald translation Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr, at archive.org.

- Can Literature Save the World? On translating Attar, Words Without Borders

- A few wikiquotes

- Attar in Encyclopedia Iranica by B. Reinert

- Attar, Farid ad-Din. A biography by Professor Iraj Bashiri, University of Minnesota.

- Attar's works in original Persian at Ganjoor Persian Library

- Deewan-e-Attar in original Persian single pdf file uploaded by javed Hussen

- Panoramic Images of Attar Tombs Neyshabur Day

- Works by Attar of Nishapur at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Attar of Nishapur

- 1140s births

- 1220s deaths

- 12th-century Persian-language writers

- Iranian Sufis

- Iranian pharmacists

- Sufi poets

- Poets from Nishapur

- Sufis from Nishapur

- Medieval Iranian pharmacologists

- 12th-century Persian-language poets

- 13th-century Persian-language poets

- 12th-century Iranian writers

- 13th-century Persian-language writers

- Poets from the Seljuk Empire

- Iranian biographers

- Iranian Muslim mystics