Cinema of Europe

Cinema of Europe refers to the film industries and films produced in the continent of Europe.

Europeans were the pioneers of the motion picture industry, with several innovative engineers and artists making an impact especially at the end of the 19th century. Ottomar Anschütz held the first showing of life sized pictures in motion on 25 November 1894 at the Postfuhramt in Berlin,[2][3] while Louis Le Prince became famous for his 1888 Roundhay Garden Scene, the first known celluloid film recorded.

The Skladanowsky brothers from Berlin used their "Bioscop" to amaze the Wintergarten theatre audience with the first film show ever, from 1 through 31 November 1895. The Lumière brothers established the Cinematograph; which initiated the silent film era, a period where European cinema was a major commercial success. It remained so until the art-hostile environment of World War II.[4] These notable discoveries provide a glimpse of the power of early European cinema and its long-lasting influence on cinema today.

Notable European early film movements include German expressionism (1920s), Soviet montage (1920s), French impressionist cinema (1920s), and Italian neorealism (1940s); it was a period now seen in retrospect as "The Other Hollywood". War has triggered the birth of Art and in this case, the birth of cinema.

German expressionism evoked people's emotions through strange, nightmare-like visions and settings, heavily stylised and extremely visible to the eye. Soviet montage shared similarities too and created famous film edits known as the Kino-eye effect, Kuleshov effect and intellectual montage.

French impressionist cinema has crafted the essence of cinematography, as France was a film pioneering country that showcased the birth of cinema using the medium invented by the Lumière brothers. Italian neorealism designed the vivid reality through a human lens by creating low budget films outside directly on the streets of Italy. All film movements were heavily influenced by the war but that played as a catalyst to drive the cinema industry to its most potential in Europe.

The notable movements throughout early European cinema featured stylistic conventions, prominent directors and historical films that have influenced modern cinema until today. Below you will find a list of directors, films, film awards, film festivals and actors that were stars born from these film movements.

History

[edit]

20th century

[edit]According to one study, "In the 1900s the European film industry was in good shape. European film companies pioneered both technological innovations such as projection, colour processes, and talking pictures, and content innovations such as the weekly newsreel, the cartoon, the serial, and the feature film. They held a large share of the US market, which at times reached 60 percent.

The French film companies were quick in setting up foreign production and distribution subsidiaries in European countries and the US and dominated international film distribution before the mid-1910s. By the early 1920s, all this had changed. The European film industry only held a marginal share of the US market and a small share of its home markets. Most large European companies sold their foreign subsidiaries and exited from film production at home, while the emerging Hollywood studios built their foreign distribution networks."[5]

The European Film Academy was founded in 1988 to celebrate European cinema through the European Film Awards annually.

Europa Cinemas

[edit]Founded in 1992 with funding from the MEDIA programme Creative Europe and from the CNC, France, Europa Cinemas is the first film theatre network focusing on European films. Its objective is to provide operational and financial support to cinemas that commit themselves to screen a significant number of European non-national films, to offer events and initiatives as well as promotional activities targeted at young audiences.[7] With the support of Eurimages and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the influence of Europa Cinemas extends to Eastern European countries, to Balkans, Eastern Europe, Russia and Turkey.

As of September 2020[update], Europa Cinemas had 3,131 screens across 1,216 cinemas, located in 738 cities and 43 countries.[7]

21st century

[edit]On 2 February 2000 Philippe Binant realised the first digital cinema projection in Europe, with the DLP Cinema technology developed by Texas Instruments, in Paris.[8][9][10]

Today US productions dominate the European market. On average European films are distributed in only two or three countries; US productions in nearly ten.[11][12] The top ten most watched films in Europe between 1996 and 2016 were all US productions or co-productions. Excluding US productions, the most watched movie in that period was The Intouchables, a French production, like most of the other movies in the top ten.[6] In 2016–2017 the only (partially) European film in the top ten of the most watched films in Europe was Dunkirk. Excluding it (which was a Netherlands, UK, France and US co-production[13]) the European film with the best results was Paddington 2, which sold 9.1 million tickets.[14]

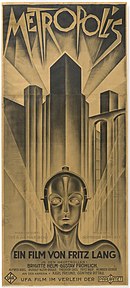

German expressionism

[edit]German expressionism surfaced as a German art movement in the early 20th century. The focus of this movement was at the inner ideas and feelings of the artists over the replication of facts. Some of the characteristic features of German expressionism were bright colours and simplified shapes, brushstrokes and gestural marks. The two different inspirations of film style that German expressionism drives from are horror films and film Noir.

Prominent German expressionism directors

[edit]

Famous German expressionism films:

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) directed by Robert Wienne

- Nosferatu (1922) directed by F. W. Murnau

- Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) directed by Fritz Lang

- Waxworks (1924) directed by Paul Leni

- Metropolis (1927) directed by Fritz Lang

World War I

[edit]The German film industry was not ready when the First World War started. In the initial days of the war's outbreak, nearly everyone in the industry was unsafe. First few victories achieved in the west changed the mood of the Germans and they became more patriotic.

As a result of this, owners of movie theaters in Germany decided to remove all English and French films from the repertoire of German movies. Around the same time, as borders underwent separation because of war and the international trade was closed, Germans couldn't really connect with the international cinema for almost a decade. Around the time July 1914 ended, there were a lot of movies in the German market.[17]

However, as the First World War started, many enemy states temporarily banned the films, and censorship decrees were introduced. All of these factors collectively caused an acute dearth of feature films. German film producers started supporting war programs of patriotic nature around the end of August 1914.

Movies started to contain scenes illustrating war-related ideas shaped by history, and the scenes were deemed historically true representation of reality. Such a depiction of war addressed all needs of classical communication criteria, so they met with economic success. Producers started making movies on many other subjects around the start of 1915. A common theme of all those movies was a successful journey of the protagonist through the war that comes as a test in the way of final destination.[17]

Censorship

[edit]While there were heavy regulations placed on the press releases, no uniform rules existed for the censorship of picture. During the course of the First World War, censors which were enacted newly also placed a ban on the movies that had been approved for production already as they were deemed unsuitable for the war. Censorship in that time was very decentralized and it deterred the surfacing of a concerted film market in Germany.[18]

The first movie company of Germany to be allowed to shoot the scenes of war officially was EIKO-film. The permission was granted on 2 September 1914.[18] However, first war movies made by EIKO-film were confiscated by the Berlin police on 12 September 1914 because of the doubts of surveillance. Such confiscation had also been observed in certain other areas of the country. It was in October 1914 when the cinemas got their first war newsreel.[18] But the engagement of theater operators in the occupied territories' military service limited film viewing. The collective effect of these limitations and censorship caused a decrease in war cinematography.

Post World War I

[edit]Unlike the war movies made in the war's initial phases, the focus of directors and producers in the war's aftermath increasingly shifted towards feature films. This laid the basis of more professional movie production. Along with that, a national movie culture started to be expressed after the war. With the increased demand for German movies, many new film making companies emerged.[18] It was a time of continuous expansion of the Berlin film industry.

From the mid-1915, German producers started making detective film series but failed to meet the demand even though they were also making serial productions related to other genres. Owing to the censorship laws and legal restrictions, the French and British movies obtained before the First World War continued to be shown in most cinemas of Germany in 1915 till a ban was imposed on them. Therefore, operators of cinemas looked for movies made by producers from neutral countries.[18]

There was a single cause of official propaganda during the initial half of the war as per the German government. The meaning and significance of war had become quite questionable by the year 1916 with the commencement of a re-evaluation of movies. Directors and producers started to consider designs suitable for the period after the end of the war.

Owing to the growing dissatisfaction of people with the military situation and increasing shortage of food, the military, and the state resolved to establish the Universum-Film AG (Ufa) on 18 December 1917.[18] It was a commercially oriented new movie making company that was found with the purpose to make feature films with just concealed propaganda.[18] The purpose to be served by these feature films was to stabilize the wartime morale and boost it.

The founders wanted to feature civilian, non-warlike and inoffensive material in the films to play a part in the victory by drawing people's attention away from the war. the First World War played an important role in the growth as well as technical changes in the laws and operation of cinema in Germany. German producers have made many artistic and technical contributions to early film technology.

Soviet cinema

[edit]Soviet Union cinema consisted of movies created by the constituent republics of the Soviet Union. Predominantly produced in the Russian language, the films reflect pre-Soviet elements including the history, language, and culture of the Union. It is different from the Russian cinema, even though the central government in Moscow regulated the movies.

Among their republican films, Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan were the most productive. Moldavia, Belarus, and Lithuania have also been prominent but to a lesser extent. The film industry was completely nationalized for a major part of the history of the country. It was governed by the laws and philosophies advocated by the Soviet Communist Party that brought a revolutionized perspective of the cinema in the form of "social realism" that contrasted with the view that was in place before the Soviet Union or even after it.[19]

The Russians had an instinct for film-making from the very start. The first film dramatized by the Russians was made in the year 1908, which gives the Russian cinematography the status of one of the oldest industries in the world. There were more than 1300 cinemas in Russia till the year 1913 and the country had produced over 100 movies which had a profound influence on the film making of the American and European origin.[20]

Censorship

[edit]Films in the Soviet Union started to be censored especially ever since November 1917 when the People's Commissariat of Education was created.[21] It was almost a month after the Soviet state was itself established. After the Bolsheviks gained strength in the Soviet Union in the year 1917, they had a major deficit of political legitimacy. Political foundations were uneasy and the cinema played an important role in the protection of the USSR's existence.

Movies played a central role at that time since they served to convince the masses about the legitimacy of the regime and their status as the bearers of historical facts. Some of the prominent movies of the time include The Great Citizen and Circus. A film committee was set up in March 1919 to establish a school view a view to training the technicians and actors so that a modest movie production schedule would be commenced. The committee was headed by a long-term Bolshevik party's member D.I. Leshchenko, In addition to looking after and ensuring the correctness of genres and themes of the film companies, Leshchenko also worked to deter the flaring up of anti-Soviet movie propaganda. It was particularly important because of the war communism in that era.

The documentaries and features of Soviet cinema thrived at their best in the 1920s. Filmmakers enthusiastically engaged themselves in the development of the first socialist state of the world. Rather than having to create money for the Hollywood film industry, the filmmakers saw this as an opportunity to focus on the education of people of the new Soviet. The first leader of the country to become the USSR and founder of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution – Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, visualized the cinema as a technological art that was best suited for a state established on the basis of the conversion of humanity by means of technology and industry.[22] Cinema took the position of the most valuable form means of art production and propagation across masses. The decade is known for experimentation with different styles of movie-making.

The 1920s

[edit]

During the 1920s, the USSR was getting a New Economic Policy. It was a decade when certain industries had a relaxed state control that provided people with a sense of mini-capitalism inside the Communist economy. That was a time of prosperity of the private movie theaters, and together with it, the whole Soviet movie industry thrived. American movies had a major influence on the Russians, unlike Soviet productions. Many Hollywood stars like Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks were idolized as heroes.

The heroic Fairbanks became a sex symbol and the contemporary star system got popularity with Pickford. The Soviet reaction to the Hollywood influence was a mix of repulsion and admiration. Near the end of 1924, Sovkino and ARK were established which were two organizations that influenced the cinema of the Soviet Union the most in the decade.[19] That was a time when the ambitious, zealous, and young film community members had bright plans for the film industry. Their efforts were directed at making the processes of production and distribution more effective and organized and raising the status of workers in the industry. In other words, they tried to publicize the cinema.

Prominent Soviet cinema directors

[edit]- Mikheil Chiaureli

- Grigori Aleksandrov

- Sergei Fedorovich Bondarchuk

- Alexander Dovzhenko

- Sergei Eisenstein

- Dziga Vertov

- Tarkovsky

Famous Soviet cinema films

[edit]- Battleship Potemkin (1925) directed by Sergei Eisenstein

- Jolly Fellows (1934) directed by Grigori Aleksandrov

- Man with a Movie Camera (1929) directed by Dziga Vertov

- Earth (1930) directed by Alexander Dovzhenko

French cinema

[edit]The rise of movement/film era

[edit]

Like the other forms of art, film cinema portrays the authenticity that faces several people. France can be considered one of the main pioneers of the entire global film industry. The proof of this claim that between 1895 – 1905 France invented the concept of cinema when the Lumière brothers first film screened on 28 December 1895, called The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station, in Paris.[23]

It lasted only 50 seconds but it launched and gave birth to the new medium of expression in the film industry. Lumiére from France has been credited since 1895 and was recognized as the discoverer of the motion camera.[23] However, despite other inventors preceding him, his achievement is often believed to be in the perspective of this creative era.[22]

Lumiere's suitcase-sized cinematography, which was movable served as a film dispensation unit, camera, and projector all in one. During the 1890s, film cinemas became a few minutes long and commenced to consist of various shots too.[24] Other pioneers were also French including Niépce, Daguerre, and Marey, during the 1880s they were able to combine science and art together to launch the film industry.[23]

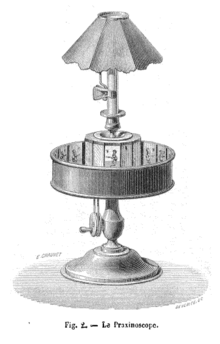

The pioneers of the French film were influenced by their historical heritage stemming from the need to express the narrative of a nation. The 19th century in France was a period of nationalism launched by the French Revolution (1789–1792).[25] Marey (1830- 1904) invented the photo gun (1882) which was developed to function and be able to have a photographic paper of 150 images in motion.[25] Emile Reynaud 1844-1918 was the founding father of animation.

The short-animated film Pantomimes Lumineuses exhibited during 1892 at the Musee Grevin was developed as a result of his invention, the Praxinoscope projector. This invention brought together colour and hand-drawn drawings.[25] Film Company was established as France's first film studio before Pathe Film Studio and founded by Gaumont (1864-1946).[23] In 1907, Gaumont was the largest movie studio in the world, it also prompted the work of the first female filmmaker Guy-Blachéwho created the film L'enfant de la barricade.[23]

Pre-and Post-World War I French Cinema

The pre-World War I period marked the influences of France's historical past with film not only galvanizing a period of advances in science and engineering but a need for a film to become a platform to explore the narrative of their culture and in doing so created a narcissistic platform.[25] Before World War I, French and Italian cinema dominated the European cinema. Zecca, the director general at Pathé Frères perfected the comic version of the chase film which was inspired by Keystone Kops.[26] Besides, Max Linder created a comic persona that profoundly influenced Charlie Chaplin's work.[26]

Other films that began pre-war in France also included The Assassination of the Duke of Guise as well as the film d'art movement in 1908.[27] These films depicted the realities of human life especially within the European society.[27] Moreover, French film produced costume spectacles that raised attention and brought global prominence before the start of World War I.[27]

Approximately 70% of the global films were imported from Paris studios from Éclair, Gaumont, and Pathe before the war.[28] However, as WWI commenced, the French film industry declined during the war because it lost many of its resources which were drained away to support the war. Besides, WWI blocked the exportation of French films forcing it to reduce large productions to pay attention to low finance film-making.[24]

However, in the years that followed the war, American films increasingly entered the French market because the American film industry was not affected by the war as much. This meant that a total of 70% of Hollywood films were screened in France.[24] During this period, the French film industry faced a crisis as the number of its produced features decreased and they were surpassed by their competitors including the United States of America and Germany.[23]

Post World War II French cinema

[edit]After the end of World War II, the French cinema art commenced its formation of the modern image as well as recognizing its after-impacts. Following the establishment and growth of the American and German film industries during the post-WWI era as well as during Great Depression.[24] Many German and American movies had taken the stage of the French and global market.[24] Moreover, during WWII, the French film industry focused mainly on the production of anti-Nazi movies especially during the late 1940s as the war came to an end.[23]

After this era, French film industry directors commenced addressing the issues affecting humanism as well focused on the production of high-eminence entertaining films.[27] In addition, the screening of French literary classics involved La Charterhouse and Rouge et le Noir attained spread great fame across the globe. Besides, Nowell-Smith (2017) asserts that one of the core cinema works that gained popularity during that period was Resnais' directed movie, Mon Amour.[24] This led to Cannes hosting their first international film festival receiving the annual status.

Styles and conventions in French cinema

[edit]The French New Wave which was accompanied by its cinematic forms led to a fresh look to the French cinema. The cinema had improvised dialogue, swift scene changes and shots that went past the standard 180 degrees axis. Besides, the camera was not utilized to captivate the audience with a detailed narrative and extreme visuals but instead was used to play with the anticipations of the cinema.[26] Classically, conventions highlighted tense control over the film making procedure. Besides, the New Wave intentionally shunned this. Movies were usually shot in public locations with invented dialogue and plots built on the fly.[27]

In several means, it appeared sloppy, but it also captured an enthusiasm and impulsiveness that no famous film could expect to equate.[27] Moreover, the filmmakers of the French New Wave usually abandoned the utilization of remixing their sound.[22] Instead, they utilized a naturalist soundtrack recorded during the capture and illustrated unaltered even though it included intrusions and mistakes. Besides, it lent the film a sense of freshness and energy like their other skills that were not in past films.[22] They used hand-held cameras which could shoot well in tight quarters generating a familiarity that more costly and more burdensome cameras could not rival.[22] A majority of the New Wave films used long, extended shots which were facilitated by these kinds of cameras.[24] Lastly, French films used jump cuts which threw the viewers out of the onscreen drama, unlike the traditional film making.

Avant-garde

[edit]This was the French impressionist cinema which denotes to a cluster of French movies and filmmakers of the 1920s. These filmmakers, however, are believed to be responsible for producing cinemas that defined cinema.[29] The movement happened between 1918 and 1930 a period that saw rapid growth and change of the French and global cinema. One of the main stimulations behind the French impressionist avant-garde was to discover the impression of "pure cinema" and to style film into an art form, and as an approach of symbolism and demonstration rather than merely telling a story.[30]

This avant-garde highlighted the association amongst realism and the camera. This was a result of "photogenie", Epstien's conception on discovering the impression of reality specifically through the camera, emphasizing the fact that it portrays personality in film.[30] The obvious film techniques utilized by the French impressionist avant-garde are slow-motion, soft-focus, dissolves, and image alteration to develop the creative expression.[30]

Prominent French impressionist film directors

[edit]Famous French impressionist films

[edit]- Nana (1926) directed by Jean Renoir

- La Femme De Nulle Part (1922) directed by Louis Delluc

- The Smiling Madame Beudet (1922) directed by Germaine Dulac

- La Dixiéme Symphonie (1918) directed by Abel Gance

- J'Accuse (1919) directed by Abel Gance

- La Roue (1923) directed by Abel Gance

- Coeur Fidéle (1923) directed by Jean Epstien

- El Dorado (1921) directed by Marcel L'Herbier

- Napoléon (1927) directed by Abel Gance

Italian neorealism

[edit]Rise of movement

[edit]

The birth of Italian neorealism, also known as the Golden Age came from living in a totalitarian society under the authority of Benito Mussolini, a nationalist, fascist leader and Prime Minister of Italy during 1922 - 1943.[32]

One of the notable turning points in Italian cinema was Italy shifting from Fascism to neorealism.[32] Mussolini has established Italy as a totalitarian state by 1925 after coming to power but it did not impact the film industry until 1926 when it took over L'Unione Cinematografica Educativa, also known as the "National Institute of the Union of Cinematography and Education".[33]

Neorealism depicts a modified view of reality, it gave the Italians a chance to go outside to the streets and portray the devastating effects of World War II on Italy. Italian neorealism films showcased unprofessional actors purposefully since they were considered low-budget films and shot them live on location spots.[34] Furthermore, they emphasized the use of non-professional actors to exhibit the artistic beauty and sense of realism in films.[34]

This particular film movement focused heavily on the working class population of Italy as it also conveyed their problems and daily life to portray the perspective of ordinary life in pre and post World War I fascist Italy.[34] Despite the leadership, it gradually impacted Italian films throughout that era, in fact only 5% of the fascist films were produced between 1930 and 1943.[33]

Fortunately, Italian neorealism actually introduced the world to the first film festival by 1932 in Venice, it was known as, the First International Exhibition of Cinematic Art.[33] Since the effect of fascism on the film industry was quite slow it was only during 1933 that a rule was enforced claiming one Italian film must be screened for every three foreign films presented.[33]

Pre and post war

[edit]Before World War I Italy's cinema was mostly dominating on a national level as a result of outstanding support from exports and the local market.[35] Italian cinema essentially began with the introduction of moving pictures in the late 1890s, in fact, the first Italian film ever was a film produced during 1896 that showcased the Queen and King's visit to Florence.[36]

The Avant-garde movement began in 1911 with experimental works and innovations on film and only a few films have been preserved form that time including The Last Days of Pompeii (1913) directed by Mario Caserini.[36]

During 1914, Italian cinema produced 1027 films, whereas a year after during 1915 only 563 films created, almost half the amount of the year prior.[33] In the same year, Italian femme fatale was introduced to the industry and established notable film actresses and stars.[36] Eleonora Duse was a famous Italian actress who was the first woman and also the first Italian on the cover of Time magazine.[37] Throughout the 1930s, Cinecittà, a film studio complex was built in Rome and was a home for Italy's star directors.[36]

The aftermath of World War II was also known as the neorealist period since that introduced the most prominent and well-distinguished filmmakers, directors and screenwriters.[32] Italian neorealism was the dominant movement in world cinema after the war, in fact it was known not only for its dedicated effort to resolve and confront societal issues but also provided an optimistic scope towards the future and maintained the clash between individuals and society.[33]

The Italian neorealism films mainly revolved around themes depicting life under an authoritative regime, poverty, and the lower class, effects of the aftermath of the war on the Italian society.[38] Despite Italian cinema being considered as auteur, it was actually as good as the Hollywood films from the Box office with the graininess, limited budget size and documentary quality like films.[39] Italian neorealism introduced a surge of films revolving around political and social conflicts but were cautious in conveying doctrinaires or signs against authority.[39] Instead, the films were heavily influenced by literature, history, art, and photography to broaden the audience's perspective and expand the horizon's of film enthusiasts.[39]

Styles and conventions

[edit]

Propaganda film styles constituted of a variety of factors with political motives in contribution to the films being produced.[33] Some of the prominent styles featured included patriotic/military films, anti-Soviet films and Italy's civilization mission in Africa of peacekeeping among other styles.[33] In contrast, regular genre films exhibited melodramas, comedies and historical costume dramas.[33] The term neorealism is defined as new realism.[40] The meaning derived from the word is quite sophisticated as it makes the audience question the extent to what is a new vs. old film, as well as it restricts its parameters in relation to society, culture and time periods.[40] Thus, Italian neorealism has designed its own distinct characteristics that are based on social realism, historical content and political devotion.[35] The films brought a surge of raw emotions between the actor and audience as a result of the relation to Marxist humanism, a concept that fulfilled the realism within the film.[35]

In order to better understand Italian neorealism one should view it through a lens of understanding the social class struggle.[34] It is essential to distinguish the lower working class minority with the wealthy high-class population and perhaps compare and contrast their circumstances to truly comprehend the social realism in Italy.[34] After conducting an overview analysis and looking at the years 1945 - 1953 it was interestingly noted that only 11% of the 822 films produced during that period would be considered neorealist films.[35]

Despite the great impact of World War II on Italy, Italian neorealism films actually rejected traditional film genres and took literary text adaptations such as Cronache Di Poveri Amanti (1954) translated as Chronicle of Poor Lovers directed by Carlo Lizzani and Senso (1954) directed by Luchino Visconti featuring romantic melodramas and historical costume dramas.[35] Films made during the Italian neorealism period portrayed a blend of routine and day-to-day life basis to emphasize the realistic elements as seen in numerous films including Bicycle Thieves (1948; also known as Ladri di biciclette) by Vittorio De Sica. The film was an accurate vivid modern representation of the social economic system (Bondanella, 2009, 86).[35] The effects of the war were everlasting and has even shaped contemporary cinema as it provided them stories worth sharing.[35]

Prominent Italian neorealism film directors

[edit]

Famous Italian neorealism films

[edit]- Rome, Open City (1945) directed by Roberto Rossellini

- Shoeshine (1946) directed by Vittorio De Sica

- Paisan (1946) directed by Roberto Rossellini

- Germany Year Zero (1947) directed by Roberto Rossellini

- Bicycle Thieves (1948) directed by Vittorio De Sica

- La Terra Trema (1948) directed by Luchino Visconti

- Bellissima (1951) directed by Luchino Visconti

- Miracle in Milan (1951) directed by Vittorio De Sica

- Umberto D. (1952) directed by Vittorio De Sica

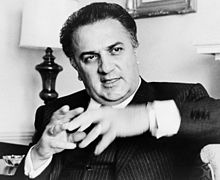

- La Strada (1954) directed by Federico Fellini

- II Posto (1961) directed by Ermanno Olmi

Film festivals

[edit]

The "Big Three" film festivals are:[42][43]

In particular, the Venice Film Festival is the oldest film festival in the world.[44]

- Others

Film awards

[edit]Directors

[edit]- French

- Céline Sciamma

- Jean Renoir

- Lumière brothers

- François Truffaut

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Louis Malle

- Jacques Audiard

- Jacques Tati

- Eric Rohmer

- Georges Méliès

- Marcel Carné

- Jean-Pierre Jeunet

- Jean Vigo

- Claude Chabrol

- Robert Bresson

- Jacques Rivette

- Roger Vadim

- Jacques Demy

- Alain Resnais

- Luc Besson

- Agnès Varda

- Bertrand Tavernier

- Belgian

- British

- Italian

- German

- Russian

- Danish

- Swedish

- Polish

- Dutch

- Turkish

- Austrian

- Other

- Pedro Almodóvar (Spanish)

- Theo Angelopoulos (Greek)

- Luis Buñuel (Spanish)

- Miloš Forman (Czech)

- Hrafn Gunnlaugsson (Icelandic)

- Dušan Makavejev (Serbian)

- Emir Kusturica (Serbian)

- Giorgos Lanthimos (Greek)

- Jiri Menzel (Czech)

- Manoel Oliveira (Portuguese)

- Otto Preminger (Austria-Hungary)

- István Szabó (Hungarian)

- Danis Tanović (Bosnian)

- Alexander Dovzhenko (Ukrainian)

- Kira Muratova (Ukrainian)

- Sergei Parajanov (Ukrainian, Armenian)

Cinematographer

[edit]- French

- Belgian

- British

- Italian

- German

- Dutch

Actors

[edit]- Charlie Chaplin

- Greta Garbo

- Ingrid Bergman

- Jeanne Moreau

- Brigitte Bardot

- Jean Gabin

- Erland Josephson

- Yul Brynner

- Max von Sydow

- Liv Ullmann

- Mads Mikkelsen

- Tatiana Samoilova

- Stellan Skarsgård

- Pernilla August

- Lena Olin

- Peter Stormare

- Alexander Kaidanovsky

- Antonio Banderas

- Anna Q. Nilsson

- Ghita Nørby

- Bibi Andersson

- Harriet Andersson

- Gérard Depardieu

- Laurence Olivier

- Ingrid Thulin

- Peter O'Toole

- Minnie Driver

- Juliette Binoche

- Marion Cotillard

- Michael Redgrave

- Vanessa Redgrave

- Nastassja Kinski

- Claudia Cardinale

- Sophia Loren

- Marcello Mastroianni

- Giulietta Masina

- Judi Dench

- Catherine Deneuve

- Catherine Zeta-Jones

- Anthony Hopkins

- Daniel Day-Lewis

- Vivien Leigh

- Audrey Hepburn

- Charlotte Gainsbourg

- Gina Lollobrigida

- Bruno Ganz

- Fanny Ardant

- Charlotte Rampling

- Isabelle Huppert

- Aleksey Batalov

- Louis Jouvet

- Isabelle Adjani

- Daniel Auteuil

- Rutger Hauer

- Famke Janssen

- Jeroen Krabbé

- Sylvia Kristel

- Carice van Houten

- Johannes Heesters

- Michiel Huisman

- Carel Struycken

- Emmanuelle Béart

- Vittorio Gassman

- Michael Caine

- Julie Christie

- Michel Piccoli

- Erich von Stroheim

- Alec Guinness

- Melina Mercouri

- Irene Papas

- Rossy de Palma

- Maurice Chevalier

- Silvana Mangano

- Kristin Scott Thomas

- Romy Schneider

- Simone Signoret

- Kate Winslet

- Derek Jacobi

- Dirk Bogarde

- Milena Dravić

- Louis de Funès

- Alain Delon

- Anthony Hopkins

- Sandra Hüller

Films

[edit]- 8 1/2 (Italy)

- Andalusian dog (France)

- Underground (Yugoslavia)

- Andrei Rublev (USSR)

- Atalanta (France)

- Ballad of a Soldier (USSR)

- Battleship Potemkin (USSR)

- Black Book (film) (The Netherlands)

- Vampire from Ferata (Czechoslovakia)

- No Man's Land (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- Viridiana (Spain)

- The Return (Russia)

- The Age of Christ (Kristove roky) (Czechoslovakia)

- All About My Mother (Spain)

- Last Year at Marienbad (France)

- The Blue Angel (Germany)

- With the Match Factory Girl (Finland)

- Daily Beauty (France)

- Road (Italy)

- Europe (Denmark)

- The Tin Drum (Federal Republic of Germany)

- Jules and Jim (France)

- Tomorrow I'll Wake Up and Scald Myself with Tea (Czechoslovakia)

- The Marriage of Maria Braun (Federal Republic of Germany)

- Wild Strawberries (Sweden)

- Mirror (USSR)

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Germany)

- Comedians (Greece)

- Lady Hamilton (United Kingdom)

- Letyat Zhuravli (USSR)

- Metropolis (Germany)

- A Man and a Woman (France)

- The Last Breath (France)

- The Sky Over Berlin (Federal Republic of Germany)

- Die Nibelungen (Germany)

- Ordinary Fascism (USSR)

- Orpheus (France)

- Pelle the Conqueror (Denmark)

- Ash and Diamond (Poland)

- Person (Sweden)

- Trains Under Scrutiny (Czechoslovakia)

- Last Tango in Paris (Italy)

- Soldier of Orange (The Netherlands)

- Bicycle Thieves (Italy)

- The Rules of the Game (France)

- Adventure (Italy)

- Road to Life (USSR)

- Rocco and His Brothers (Italy)

- Sexmission (Poland)

- Sweet Life (Italy)

- The Word (Denmark)

- The Servant (United Kingdom)

- Death in Venice (Italy)

- The Passion of Joan of Arc (France)

- The Third Man (United Kingdom)

- Three Colors (France)

- Fanfan-Tyulpan (France)

- Blowup (United Kingdom)

- Hiroshima, My Love (France)

- Man of Marble (Poland)

- Man with a Movie Camera (USSR)

- 400 Blows (France)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (France)

- Turkish Delight (1973 film) (The Netherlands)

- Pandora's Box (Germany)

- I Killed Einstein, Lord (Czechoslovakia)

- Underground (Yugoslavia)

- Dry Summer (Turkey)

- Hababam Sınıfı (Turkey)

- Yol (Turkey)

- Head-On (film) (Germany, Turkey)

- Uzak (Turkey)

- Amélie (France)

- A Very Long Engagement (France)

- La Vie en Rose (France)

- Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Turkey)

- Winter Sleep (Turkey)

- Two Days, One Night (Belgium)

- Portrait of a Lady on Fire (France)

- Close (Belgium)

See also

[edit]- List of cinema of the world

- List of European films

- Cinema of the world

- World cinema

- European Film Promotion

- Media Plus

- Film festivals in Europe

References

[edit]- ^ "Cinecittà, c'è l'accordo per espandere gli Studios italiani" (in Italian). 30 December 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Ottomar Anschütz, Kinogeschichte, lebender Bilder, Kino, erste-Kinovorführung, Kinovorführung, Projektion, Kinoe, Bewegungsbilder".

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EArkp5YYTLA

- ^ Rose of Sharon Winter (2008). "Cinema Europe: The Other Hollywood". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Bakker, Gerben (1 May 2005). "The decline and fall of the European film industry: sunk costs, market size, and market structure, 1890–19271" (PDF). The Economic History Review. 58 (2): 310–351. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00306.x. ISSN 1468-0289. S2CID 154911288.

- ^ a b Comai, Giorgio (9 April 2018). "Europeans at the cinema". OBC Transeuropa/EDJNet. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Presentation". Europa Cinema. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Cahiers du cinéma, n°hors-série, Paris, April 2000, p. 32 (cf. also Histoire des communications, 2011, p. 10. Archived 2 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Cf. Binant, " Au cœur de la projection numérique ", Actions, 29, Kodak, Paris, 2007, p. 12. Archived May 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Claude Forest, « De la pellicule aux pixels : l'anomie des exploitants de salles de cinéma », in Laurent Creton, Kira Kitsopanidou (sous la direction de), Les salles de cinéma : enjeux, défis et perspectives, Armand Colin / Recherche, Paris, 2013, p. 116.

- ^ Christian Grece (May 2018). How do films circulate on VOD services and in cinemas in the European Union? (Report). European Audiovisual Observatory. p. 20. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Bona, Marzia (14 February 2018). "Europeans at the cinema, from East to West". OBC Transeuropa/EDJNet. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "Dunkirk". British Film Council. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Cebrián, Sergio (5 July 2018). "European cinema regains ground". VoxEurop/EDJNet. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "Fritz Lang: 10 essential films". 4 December 2015.

- ^ Marriott, James; Newman, Kim (2018) [1st pub. 2006]. The Definitive Guide to Horror Movies. London: Carlton Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-78739-139-0.

- ^ a b "The German Film Industry and the First World War". @GI_weltweit. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Film/Cinema (Germany) | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ a b Youngblood, Denise J. (1991). "The New Course". Soviet Cinema in the Silent Era, 1918–1935. University of Texas Press. pp. 39–62. doi:10.7560/776456. ISBN 9780292776456. JSTOR 10.7560/776456.8.

- ^ Markov, Arsenii (19 July 2018). "5 ways Soviet directors revolutionized filmmaking". www.rbth.com. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Levaco, R. (1984). Censorship, Ideology, and Style in Soviet Cinema. Studies in Comparative Communism. 18 (3&4): 173-183.

- ^ a b c d e Harrod, Mary (June 2016). "Nationalism and the Cinema in France: Political Mythologies and Film Events, 1945–1995". French History. 30 (2): 282–283. doi:10.1093/fh/crw019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Armes, Roy (1985). French Cinema. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey (2017). The History of Cinema: A Very Short Introduction (First ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198701774.

- ^ a b c d Hayward, Susan (1993). French National Cinema. London: Routledge.

- ^ a b c Sieglohr, Ulrike (6 October 2016). Heroines Without Heroes: Reconstructing Female and National Identities in European Cinema, 1945-51. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781474287913.

- ^ a b c d e f Morari, Codruţa (2017). The Bressonians: French Cinema and the Culture of Authorship. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78533-571-6.

- ^ King, Gemma (2017). Decentring France: Multilingualism and Power in Contemporary French Cinema. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9781526113597.

- ^ Sieglohr, Ulrike (6 October 2016). Heroines Without Heroes: Reconstructing Female and National Identities in European Cinema, 1945-51. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781474287913.

- ^ a b c O'Pray, Michael (2003). Avant-Garde Film: Forms, Themes and Passions. London: Wallflower. ISBN 9780231850001. OCLC 811411545.

- ^ "Vittorio De Sica: l'eclettico regista capace di fotografare la vera Italia" (in Italian). 6 July 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ a b c "Deep focus: The roots of neorealism | Sight & Sound". British Film Institute. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey (1996). The Oxford History of World Cinema. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198742425. OCLC 642157497.

- ^ a b c d e "Italian Neo-Realism". Film Theory. 7 June 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bondanella, Peter (2009). A History of Italian Cinema. New York City: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. ISBN 9781501307638. OCLC 1031857078.

- ^ a b c d "Italian Film - A Brief History of Italian Films". www.italianlegacy.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Eleonora Duse | Italian actress". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Evolution Of Italian Cinema: Neorealism To Post-Modernism". Film Inquiry. 25 May 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Morris, Roderick Conway (17 November 2001). "Neorealism in Postwar Italy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ a b Wybrew, Phil de Semlyen, Ian Freer, Ally (8 August 2016). "Movie movements that defined cinema: Italian Neorealism". Empire. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Federico Fellini, i 10 migliori film per conoscere il grande regista" (in Italian). 20 January 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Bordwell, David (2005). Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. University of California Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780520241978.

Because reputations were made principally on the festival circuit, the filmmaker had to find international financing and distribution and settle for minor festivals before arriving at one of the Big Three (Berlin, Cannes, Venice).

- ^ Wong, Cindy Hing-Yuk (2011). Film Festivals: Culture, People, and Power on the Global Screen. Rutgers University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780813551104.

Whether we talk about the Big Three festivals—Cannes, Venice, Berlin—look at Sundance, Tribeca, and Toronto in North America, or examine other significant world festivals in Hong Kong, Pusan, Locarno, Rotterdam, San Sebastián, and Mar del Plata, the insistent global icons of all festivals are films, discoveries, auteurs, stars, parties, and awards.

- ^ Anderson, Ariston (24 July 2014). "Venice: David Gordon Green's 'Manglehorn,' Abel Ferrara's 'Pasolini' in Competition Lineup". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016.

External links

[edit]- Europa Cinemas

- Top 10 movies from Spain according to IMDB.com

- Cineuropa

- European Cinema Research Forum

- European Film Promotion

- French Trade-Union article about cinema in Europe, May 2009

- 7 Surprising European Films A look at European game changers from 2000 to 2011

- European Audiovisual Observatory

- European Film Industry Statistics

- LUMIERE European Cinema Database