Draft:History of Aix-les-Bains

| Submission declined on 14 October 2024 by Tavantius (talk). The content of this submission includes material that does not meet Wikipedia's minimum standard for inline citations. Please cite your sources using footnotes. For instructions on how to do this, please see Referencing for beginners. Thank you.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

The history of Aix-les-Bains is directly linked to the Lac du Bourget and above all to its hot springs, which made it one of the world's most renowned spa resorts. A historical analysis of the town of Aix-les-Bains must be read in conjunction with the history of Savoy, if one is to better understand its evolution and cultural influences.

Chronological history

[edit]The origins

[edit]During the Neolithic period (between 5000 and 2500 BC), sedentary communities established settlements along the shores of Lac du Bourget. Underwater archaeological excavations have revealed evidence of "lake cities", awith at least two such sites located near the Aix shore, specifically in the areas of Grand Port and Baie de Mémars. These archaeological remains were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011.[1][2]

Additionally, traces of Celtic occupation have been identified around the thermal springs in the town center, including a dedication to the spring god, Borvo.[3][4]

Aquae: Roman Aix

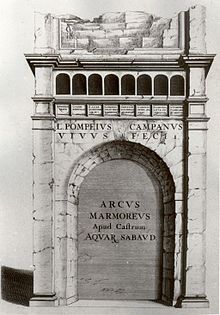

[edit]Historians generally agree that Aix’s origins can be traced to its thermal springs during Roman times, built upon the remains of an earlier Celtic settlement. According to Alain Canal,[5] initial occupation of the site dates to the 1st century BC. However, there is no evidence to suggest that these early structures represented a permanent settlement. The surviving architectural remains predominantly consist of public buildings, which complicates the identification of an ancient "Aquae." Epigraphic evidence, however, documents the administrative status of the site in the 1st century AD, indicating that Aix functioned as a "vicus", governed by a council of ten members, or "decemlecti". Administratively, it was part of the territory of the city of Vienne.[6] A small number of citizens inhabited the area, and some were evidently prosperous enough to make offerings to the gods, such as the establishment of a sacred grove or vineyard. The Campanii family, for instance, constructed a funerary arch.

Archaeological excavations have uncovered a substantial spa complex near the thermal springs.[7] On a lower terrace to the west, the funerary arch of Campanus, likely erected in the 1st century AD, has been found. Further downstream, on a second terrace, a temple dedicated to Diana replaced an older circular structure in the 2nd century AD, presumably around the same time as the construction of the arch. Additional remains of necropolises have been discovered to the north of the temple. The Parc des Thermes and various other locations throughout the city contain a diverse array of artifacts, including pottery and remains from necropolises. However, no particularly remarkable finds have been identified to justify extensive archaeological excavation. As a result, our understanding of the Gallo-Roman vicus of Aquae remains limited, particularly in terms of its size, layout, and daily life. The locations of Roman residences, farms, and staff settlements, as well as the specific activities within the vicus, are still unclear. Available insights are primarily derived from the archaeological map created by the DRAC's (Regional Directorate of Cultural Affairs) archaeological services. Alain Canal remarks, "Paradoxically, while Aix has yielded numerous documents demonstrating the antiquity of the site and the quality of its early imperial urban planning, we still lack a clear understanding of the town's layout".

The historical development of the site can be summarized as a continuous occupation beginning in the 1st century BC,[8] followed by gradual expansion through the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. This period saw the progressive development of the spa complex, around which monumental buildings were constructed on a system of terraces, with the layout evolving several times during the Roman era. While the presence of hot springs in the site's selection, other considerations, such as the favorable geographic location, may have also played an important role in its development.

From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance

[edit]

Our knowledge of the history of Aix, already poor in Roman times, is further obscured by the lack of sources for the late Roman Empire and the early Middle Ages. We are reduced to conjecture by studying the destruction caused by the barbarian invasions, which left traces of fire on the Gallo-Roman villas in the vicinity (Arbin). In any case, Aix's Roman thermal baths fell into ruin from the 5th century onwards, and traces of urban development were lost.

Aix is only mentioned again in sources in the 9th century, in 867, and then in 1011 through charters. In the second, King Rudolf III of Burgundy donated the villa of Aix, described as a royal seat, with its settlers and slaves, to his wife Ermengarde, who in turn transferred it to the bishopric of Grenoble.[9] From this charter, we learn that Aix was a town with a church and agricultural estates. At the beginning of the 12th century, the Great Saint Hugues, Bishop of Grenoble, donated the land to the Saint-Martin de Miséréré monastery. The monastery established the church as a priory-cure under the patronage of Sainte Marie. At the end of the 12th century, the cartulary of Saint Hugues reveals the existence of two other parishes, that of Saint Simond with its church, and that of Saint Hippolyte (now a suburb of Mouxy), which also had a small priory. The urban geography begins to become clearer: you have to imagine the small town, enclosed within its ramparts, which nobody knows when they were built. The town's focal point is the priory, close to the ancient Roman temple. This may also have been the administrative center, since at least since the 13th century, Aix has been a seigneury under the control of the de Seyssel family,[10] who owned a castle there, which, although we can't place it with any certainty, was probably on the site of today's castle.[11] Two hamlets are attested: Saint Hyppolyte, in the immediate vicinity of the town but outside the ramparts, with a small priory at its center, and next to it, currently under the Villa Chevalley, a fortified house belonging to the Savoy family that the latest studies date to the 13th century. A second important village appeared, Saint-Simond (Saint-Sigismond), which also had a church and cemetery, and was erected as a parish, a dependent member of Saint Hyppolyte.

Textual evidence suggests the existence of other villages, of which there is no certified trace until 1561 when the population was counted for the salt tax.[12] At that time, of Aix's 1,095 inhabitants, 46% lived in the town; Saint-Simond had 125 inhabitants, Puer 91, Choudy 87, Lafin 86, and the remaining ten or so hamlets shared the rest (Marlioz having escaped our sources). This settlement geography seemed to remain unchanged until the end of the 19th century.[13] The neighboring abbey of Hautecombe owned a fairly large estate in the upper Saint-Simond area of Aix.

In the early 16th century, the ancient church of Sainte-Marie fell victim to a devastating fire. To rebuild it, the people of Aix called on Claude de Seyssel, a member of the town's noble family, who had risen to the dignity of bishop. He was bishop of Albi, and above all private advisor to the French king Louis XII. He was also the author of a number of legal treatises. Thanks to his support, the De Seyssel family was able to build a collegiate church with a chapter of twelve canons, headed by a dean appointed by the count. A church was built on the square next to the cemetery, with a flamboyant Gothic choir. While the choir belonged to the collegiate church, the nave belonged to the parishioners and was more basic in appearance. The poorly constructed vault collapsed in 1644. One of the side chapels was reserved for the De Seyssel family of Aix, who buried their dead there. The collegiate church, which became a parish church after the French Revolution, was demolished in 1909 when the new church was built. This church was known for housing a relic of the True Cross, which was venerated from far and wide. It was also at the end of the Middle Ages that the château seigneurial d'Aix was rebuilt.[14] The ceiling of the main hall on the first-floor dates from 1400, while the magnificent grand staircase was built around 1590.

The 18th century, the Victor Amédée III thermal baths, the Revolution

[edit]On April 9, 1739, a gigantic fire broke out in the town center, destroying 80 houses - almost half the town.[15] To rebuild, the town appealed for subsidies from the King, who imposed an alignment plan to be carried out by the engineer Garella. This plan went further than a simple reconstruction plan, since it provided for a real alignment of the streets, and imposed certain town-planning rules: such as the construction of two-story houses with a first floor; it also prohibited thatched roofs. However, it was very limited in scope, since it only concerned the burnt-out district, i.e. the main street (rue Albert Ier), the central square (Place Carnot), and the rue des Bains. This plan was applied until 1808, but only sporadically, as the local authority had no money to buy the houses to be demolished in alignment, and owners were simply forbidden to carry out renovation work until they had to completely rebuild their crumbling buildings. By the early 17th century, the people of Aix and the medical world had begun to be made aware of the value of Aix's hot springs, thanks to the famous writings of Dauphin physician Jean Baptiste Cabias, who was followed in this field by other renowned physicians. The use of hot springs has never been forgotten since antiquity. In the Middle Ages and right up to the end of the 18th century, people bathed in Aix, either in the only surviving Roman open-air swimming pool, or in their own homes, where thermal water was brought in by porter. According to Jean Baptiste Cabias, King Henri IV of France greatly appreciated his Aix-en-Provence bath.[16] In 1737, in order to protect the thermal waters from infiltration by the stream that ran through the town, a major project was scheduled by the Intendance Générale. This modified the urban layout of the town center since a new bed had to be dug for the ruisseau des Moulins outside the ramparts. It was also necessary to rebuild the Marquis d'Aix's four mills, previously located in the town center, along the new canal (now known as montée des Moulins).

Aix owes its renaissance to the Duc de Chablais, son of King Victor Amédée III, who, after tasting the benefits of the springs and finding himself inadequately housed there, suggested to the king that a spa be built. In a royal decree dated June 11, 1776, King Victor Amédée III commissioned the comte de Robiland to draw up plans for a bathing establishment. This was built between 1779 and 1783 under the direction of engineer Capellini.[17] This date also marked the beginning of the demolition of the old town center, as following this imposing construction, the area around the houses began to be cleared to create a square.

This first spa became an important factor in development. Throughout this period and up until the French Revolution, the town welcomed a roughly stable number of spa-goers, around 600 a year, the majority of whom were French. Subsequently, the population grew, reaching 1,700 in 1793. In 1783, to make life more pleasant for spa-goers, the Commune Council commissioned the construction of a landscaped public promenade: the Gigot, now known as Square A-Boucher. It was lined with chestnut trees and designed by architect Louis Lampro. Apart from private gardens, this was the birth of the first urban planning act concerning green spaces, which gave a boost to the development of the town on this side of the ramparts, along the Route de Genève.

In 1792, French revolutionary troops under the command of Montesquiou entered Savoie. The spa industry came to a standstill. The Thermes were requisitioned by the armies of the Republic, which sent wounded soldiers there to convalesce. But it was also an opportunity to introduce Aix to a wider public. Aix became Aix-les-Bains. The Revolution abolished the privileges of the local nobility, and above all allowed the town to avoid paying the lord marquis of Aix the large sum of money it owed him following the purchase of seigneurial rights (the town had no charter of franchise). In addition, freedom of trade gave a new impetus to the creation of an economy based on the exploitation of thermal springs, once peace had been restored. This led to the development of guesthouses, hotels and cabarets. The Revolution, however, left its mark on church property: the collegiate church was abandoned, and the bell tower and church furnishings were destroyed. It's by the lake that you'll find something new. Puer's small harbor mole, built under the Ancien Régime (1720), became a full-fledged port. Initially used by boats supplying the troops of the Armée des Alpes, and equipped with a military store, it was gradually developed for the export of goods, notably glassware from the workshops set up along the lake. From then on, it was known as the Port de Puer. The development of this district led to the upgrading of the "Avenue du Lac", and all this activity attracted the first buildings lined up along this busy thoroughfare, outside the center and existing villages. It would seem that the revolutionary period also had a significant influence on village development, simply by breaking up the old noble property and removing the heritage of the churches in these areas, but historical research into the evolution of land ownership remains to be done in this area. On the outskirts of the villages, a number of previously non-existent pre-industrial activities emerged: the creation of mills, sawmills, and hydraulic forges.

The French Revolution

[edit]

The seeds of the Revolution were well known and widespread, among the bourgeoisie and part of the artisan and working classes of Aix-les-Bains, thanks to the many Savoyards living and working in Paris, not to mention the writings of Genevans Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. On the night of September 21-22, 1792, General Moutesquiou's French troops crossed the border to invade the Duchy of Savoy by surprise, forcing the Savoyard army, the king, and many civil servants and clergy to take refuge in Piedmont.[18] At the end of October, the Allobroges Assembly, meeting in Chambéry cathedral, declares the end of despotism, the abolition of corvées and gabelle, the end of the militia, and the creation of the Mont-Blanc department by uniting the six Savoy provinces. The people of Aix became French for 23 years. The welcome given to the French troops was at first rather enthusiastic, as the Duke of Savoy had fled and the inhabitants had a real sense of liberation. However, the mass mobilization of men, the flight of the nobility and clergy, who had taken refuge in Piedmont, and the anti-religious policies of the representatives of the Revolution, eventually exasperated the Savoyards and led them to revolt. Aix-les-Bains remained a French town until the fall of the Napoleonic Empire, which enabled the House of Savoy to reclaim their lands. Anne-Marie Claudine Bédat, Baroness Brunet de Saint-Jean-d'Arves by marriage to Noël Brunet, owned the Château d'Aix-les-Bains,[19] now the town hall, which she sold to the Marquis de Seyssel in 1821.

The Second Empire

[edit]Aix-les-Bains became definitively French on April 22, 1860, the year in which the Treaty of Turin was signed and the people of Aix voted 1,090 in favor and 13 against the attachment of Savoy to France.[20] The move was symbolically celebrated by an official visit from Napoleon III. On August 29, 1860, he visited the Aix spa amid a profusion of garlands and cheers.[21]

The Belle Époque (1890-1914)

[edit]

A flagship town of the Belle Époque, Aix-les-Bains was a major resort for princely families and the wealthy until the 1960s. This is evidenced by the many palaces that dominate the town and have now become condominiums. Queen Victoria, who was served by the Café des Bains and the Grand Cercle, among others, the Belgian King Albert I and the Aga Khan were all regulars in this city of water, where they also came for entertainment. The town owes it to them for the creation of a golf course, a tennis club, and a racecourse. Several of Sacha Guitry's plays and stories, notably Confessions of a Cheat, are set in Aix-les-Bains. Queen Victoria was a regular visitor. Given her rank and for diplomatic reasons, she came discreetly under the title of Countess of Balmoral. In love with the town's charms, the benefits of its waters, and its climate, the Queen wanted to build a residence on the hill of Tresserve and establish a real estate there. Unfortunately, in 1888, although the project was decided upon, it was not carried out. During this period, life in Aix was extremely pleasant not only for the powerful of the time but also for all the artists who found it a unique place of inspiration. The man who best sublimated Aix-les-Bains and its Lac du Bourget was unquestionably Alphonse de Lamartine. The poet was already present on October 1, 1816. In some of his writings, he recounts his arrival in the town he calls Aix-en-Savoie. He stayed in a boarding house on the hillside. This literary figure from the Romantic movement represents this spirit well. Indeed, he saved his neighbor at the time, Mlle Julie Charles, who was suffering from tuberculosis, from drowning on his way to Hautecombe by the lake. A short-lived, passionate romance ensued. Aix-les-Bains was a town bursting with activity and festivities. A dead town in winter, its contrast in summer was striking. In those days, Aix-les-Bains was the capital of the aristocracy and European socialites of the 19th and early 20th centuries during the summers of that era. Guy de Maupassant also fell under the spell of the historian-philosopher Taine, whom he met in Aix-les-Bains. Prince Nicholas of Greece's family had close ties with most of the European royal courts, and the young man spent his summers between Aix-les-Bains and Denmark, where he met up with his foreign cousins. There, he became known as "Greek Nicky", which set him apart from his cousin, the future Nicholas II of Russia.

The First World War

[edit]

Although the First World War officially began in 1914, it had been a long time in the making. As early as 1901, 45 beds were reserved at the Hospice Thermal (Reine Hortense) in Aix-les-Bains. These were to be made available to the military authorities once war was declared. In agreement with the municipality of Aix-les-Bains, the Ministry of War had planned to set up two auxiliary hospitals in the spa town following the actual outbreak of hostilities. One was created in 1911 on boulevard des Anglais in the Bernascon high school, and the other a few years later, in 1913, at 2 rue Lamartine in the girls' high school.[22] On August 5, 1914, the president of the Union des Femmes declared her hospital, located in the upper elementary school, ready to receive war wounded. On August 8, the Société de Secours aux Blessés Militaires publicly and officially announces the opening, on August 10, of the Auxiliary Hospital at Bernascon High School. The prefecture was quick to inform the municipality of Aix-en-Provence on August 14, asking it to clear its hospitals of all wounded who could be treated outside, to make room for the wounded soldiers.[23] On August 28, the casino administration made the Grand Cercle and the Villa des fleurs available to the municipal coordination committee. On the same day, the Savoie prefecture received a message from the military governor of the 14th region, stating: "For diplomatic reasons, please postpone the organization of hospitalization of wounded soldiers in the neutralized Savoie zone", followed three days later by a new dispatch stating: "Hospitalization of wounded soldiers, including Germans, in Aix-les-Bains, neutralized zone, impossible without ministerial instructions". These messages made it impossible to admit wounded soldiers to either Haute-Savoie or the part of Savoie mentioned in the 1815 Treaty of Paris, where the town of Aix-les-Bains is located.

However, on September 2, the prefecture transcribed a telephone conversation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stating: "The Minister of Foreign Affairs declares most formally that we must not place in Aix-les-Bains any French wounded likely to return to the Armies. However, there does not seem to be any disadvantage in having French or German wounded who are very seriously injured, whose lives are in danger or who are presumed not to recover before the end of hostilities, placed in a neutral zone". Finally, on September 4, the same ministry telegraphed the prefecture: "From the point of view of the French interpretation of treaties, Aix-les-Bains should be considered as being outside the neutral zone; consequently, there is no reason not to hospitalize the wounded there". Although Aix-les-Bains was suddenly no longer part of the neutral zone, a remnant of Savoie's attachment to France, Haute-Savoie remained within it. As a result, the Red Cross committees in this département moved to the neighboring département of Savoie. The Annecy, Annemasse, and Evian committees were all based in the town of Aix-les-Bains. In September 1914, the health service had 1,135 beds at its disposal in the spa town.

On September 10, a train brought 330 wounded to the town. On the night of September 12 to 13, 1914, 85 wounded were also transported.[24] On the same day, the Grand Cercle ambulance improvised an additional 200 beds in the games room and the halls of the Café and Theatre.[25] Two operating theatres were set up in the small room against the bridge room and the north-west gallery. By October 1, 1914, the town was receiving a massive influx of wounded soldiers. There were 1,180 of them. They were divided into 14 care units. In September, six new hospital units were created. They were set up in the city's major palace hotels: the Beau-Site, the Régina-Bernascon, the Grand-Hôtel d'Aix, the Continental du Nord and the Mercédès. At the Aix-les-Bains town council meeting on October 5, 1914, three main requests were made. These were: that the doctors from Aix who were currently mobilized should be brought back; that the health service should be asked to send only slightly wounded soldiers to Aix, as surgical staff were lacking and operating theatres, apart from the one at the Hôpital Municipal, were ill-equipped to treat the seriously wounded. A final request concerned the possibility of not transporting the wounded in cattle cars. In the spring of 1915, although the war was still going on, life in the rear was getting back to normal.[25] At the end of May, the town's mayor made an official request to the authorities to free up the Grand Cercle d'Aix-les-Bains, which since the start of the war had become what is commonly known as the convalescent hospital. The town's chief magistrate said: "At a time when Savoie is opening up, it is absolutely essential for us to provide our visitors and bathers with the maximum possible amenities". After examining the request, the evacuation of the Grand Cercle building began on November 12 and was completed on January 15, 1916. The following year, a number of hotels were also vacated, making it possible to welcome spa guests.[23][25]

Between the wars

[edit]The construction of Lyon's Sacré-Coeur church, for which the foundation stone was laid in 1922, required considerable savings. Instead of the ashlar originally planned, white reconstituted stone was used, supplied by the Boschetto company in Aix-les-Bains. Aga Khan III married Andrée Joséphine Carron (1898 - 1976) on December 7, 1929, in a civil ceremony in Aix-les-Bains and on December 13, 1929, in a religious ceremony in Bombay (India). The daughter of an artisan butcher, she worked as a saleswoman in a candy store, and then as co-owner of a hat store.[26] After this marriage, she became Princess Andrée Aga Khan. They had a son: Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, in 1933.[27]

The Second World War

[edit]On January 31, 1942, Laure Mutschler married Eugène Diebold, who had fled to Lyon with her. In July 1942, they were arrested for the first time, but the two resistance fighters were released for lack of evidence. Taking refuge in Aix-les-Bains, Laure Diebold went underground and became "Mona". She joined the Free French Forces and was Jean Moulin's secretary, before being arrested and deported.[28]

Thematic history

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]Aix-les-Bains, founded in the 1st century AD, is rarely referenced in ancient epigraphic texts and is not mentioned by well-known Roman authors. However, two inscriptions preserved in the local archaeological museum refer to "Aquae" (the Waters) and "Aquensis" (the inhabitants of the place of the Waters), providing some information about this vicus, which was under the influence of the city of Vienne. Nineteenth-century historians equated the name of Aix-les-Bains with these references.

The inscriptions include terms such as "Aquae Allobrogium, Aquae Gratianae" (an inscription displayed on the pediment of the Thermes Nationaux from 1934 to 1968), and "Allobrogum Aquae Gratianae".[29] In 1011, the name Aquae appears in the charter of donation by King Rodolphe III of Burgundy, granting the royal land of Aix (de Aquis) to his wife, Ermengarde. Medieval texts also mention "Aquae Grationapolis", with the suffix indicating Aix's affiliation with the diocese of Grenoble. The first documented use of the name "Aix-les-Bains" dates to September 1792, in a letter from a French soldier recovering at the local thermal waters. This name later appeared in official documents, including town council deliberations. At the beginning of the 19th century, some literary works used the name "Aix en Savoie", but it was never adopted in administrative contexts. Since 1954, the Aix-les-Bains train station has been officially known as "Aix-les-Bains - Le Revard", following a request by the town council.

Heraldry

[edit]Thermal baths

By 1806, visitor numbers had returned to the highs of the Ancien Régime, at 800 per year, but by 1809 they had risen to 1,200 and three years later to almost 1,800. The Restoration saw the confirmation and continuation of this success. Aix retained its pre-eminence. In 1848, Aix boasted 4,800 visitors, six times more than Evian and Saint-Gervais, and sixteen times more than La Caille and Brides.[30] Architect Pierre Izac was involved in the construction of one of Aix-les-Bains' thermal baths.[31] In 1933, Gentil & Bourdet, both renowned ceramists, counted among their main achievements multiple works at the Thermes nationaux d'Aix-les-Bains (Pétriaux).[32]

Negotiations for Moroccan independence

[edit]

Morocco's independence negotiations took place in Aix-les-Bains. At the Aix-les-Bains conference in September 1955, the French Prime Minister, Edgar Faure, publicly summarized the compromise proposed to Morocco, under the slogan "Independence in interdependence". Until then, the Moroccan territory had been legally under French protectorate, with the exiled Mohammed Ben Youssef as sultan. Negotiations were held in the presence of numerous French and Moroccan personalities and organizations. On the Moroccan side, the Democratic Independence Party (P.D.I.) and the Istiqlal party were represented by Mehdi Ben Barka, Omar Benabdejlil, Abderrahim Bouabid, and M'hamed Boucetta. The French delegation included Edgar Faure,[33] Pierre July, Robert Schuman, and other members of the government. So much for the main protagonists. Alongside them, guests from all walks of life were invited to give their informed opinions on the condition of Morocco and its independence. Loyal allies of the protectorate and traditional Moroccan chiefs were invited. So they too could negotiate in the presence of the parties concerned. To the disappointment of the Istiqlalites, they were given precedence. Although the Aix-les-Bains negotiations played an important role in Morocco's march towards independence, the fact remains that France had taken great care to prepare this transition in advance. Indeed, the French state of the time was convinced of the need to allow independence for this North African territory. However, because of the many economic interests at stake and the numerous business relations with the pashas and caïds, to name but a few, France took care not to rush this transition and to initiate the change gently. The destiny of the Kingdom of Morocco's sovereignty was shaped during the Aix-les-Bains conference. Officially, negotiations resulted in an agreement to create an independent state. Following this, Sultan Ben Arafa abdicated, and Sultan Mohammed Ben Youssef took over after returning from exile. Morocco was definitively proclaimed independent in the Declaration of La Celle-Saint-Cloud. Recently, the fiftieth anniversary of the negotiation of the Moroccan independence agreements was celebrated.[34] A fountain with a Moroccan zellige basin was created for the occasion. Mâalem craftsmen came specially from their spiritual capital to create the fountain in Aix-les-Bains' verdant park. The project was supported by the Regional Tourism Council (CRT-Fès) and the Tourist Office.

Transport and communications

[edit]

The current Maurienne line, a major axis of the French rail network, includes the Aix-les-Bains to Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne line, opened on August 1, and the Saint-Innocent to Aix-les-Bains line, opened on August 31, 1857. In 1867, the PLM company took over the line, with the exception of the Aix-les-Bains - Chambéry section. From 1896 onwards, Aix-les-Bains was equipped with the Mékarski compressed-air tramway.[35]

From 1950 to 1953, the Ligne de Savoie Aix-les-Bains - La Roche-sur-Foron used an electric voltage of 20,000 V and a frequency of 50 Hz for its electric rail traction. The Z 9055 is a former SNCF prototype electric railcar powered by alternating current at industrial frequency, i.e. the standard 50 Hz frequency supplied by EDF. This experiment took place on theÉtoile de Savoie, the first section of which was Aix-les-Bains - Annecy.

August 15, 1992, marked the centenary of the installation of the Mont-Revard railroad.[36] On July 1, 1950, the first trials in France of electric traction using 20 kV - 80 Hz single-phase industrial current took place between Aix-les-Bains and La Roche-sur-Foron.[37]

Sports

[edit]Several stages of the Tour de France have taken place in Aix-les-Bains, including those in 2001, 1998, 1996, 1991, 1989, 1960, and 1958.[38][39][40][41][42] The Classique des Alpes, a cycling race established in 1991 and discontinued in 2004 with the introduction of the Pro-Tour,[43] passed through the Chartreuse and Bauges mountain ranges. In 1960, Fernando Manzaneque won the 215 km 18th stage, which ran from Aix-les-Bains to Thonon-les-Bains.[44]

Guy Husson, a French hammer thrower, was a member of AS Aix-les-Bains from 1965 to 1983. He achieved remarkable success, winning the French hammer championship 15 consecutive times from 1954 to 1968.[45]

Paul Arpin, a French long-distance runner, was a member of AS Aix-les-Bains until 1990, and then again of AS Aix-les-Bains from 1993 to 1995. He was numerous times French champion in his discipline, as well as European champion.[46]

On August 18, 1965, Pancho Gonzales lost the final of the Aix-les-Bains Pro Championships tennis tournament to Alex Olmedo.[47] The final score was 2-6 11-9 6-3. Rodney George "Rod" Laver is a former Australian tennis player. He is the only player to have achieved the Grand Slam twice: in 1962 as an amateur and 1969 as a professional.[48]

The World 3-cushion Championship was held in Aix-les-Bains in 1983. The winner was Belgian Raymond Ceulemans, followed by Frenchman Richard Bitalis and Japanese Nobuaki Kobayashi.[49] In 1990, Richard Chelimo became Junior World Champion at the World Championships in Aix-les-Bains.[50][51]

The same year, Paul Kipkoech won the team gold medal at the World Cross-Country Championships in Aix-les-Bains.[52] On June 22, 2002, Grégory Gabella, a French high jumper and member of AS Aix-les-Bains, won the European Athletics Nations' Cup with a personal best of 2.30m.[53]

In soccer, during the 2006-2007 season, on July 26, the Ligue 1 club Paris Saint-Germain played a friendly match against the Spanish team Celta Vigo to a 1-1 draw.[54]

The French Chess Championship has been held in Aix-les-Bains on several occasions. In 2003, chess player Étienne Bacrot won the championship ahead of Joël Lautier and Andreï Sokolov.[55] In 2007, chess player Maxime Vachier-Lagrave won the championship ahead of Vladislav Tkachiev and Andreï Sokolov.[56]

Personalities

[edit]Aix personalities

[edit]

List of personalities who were born or lived in the town of Aix-les-Bains.

- Gaspard François Forestier (1767–1832) - A French general during the French Revolution and the First Empire, he was honored as Commander of the Legion of Honor.[57]

- François Louis Forestier (1776–1814) - A French brigadier general, he was elevated to the rank of baron of the Empire and became an officer of the Legion of Honor.[57]

- Jean Claude Nicolas Forestier (1861–1930) - A landscape architect and urban planner, he contributed significantly to the development of Paris.[58]

- Jean de Sperati (1884–1957) - Noted as one of the foremost forgers of his era, he was recognized as a master of counterfeit collector's stamps.[59]

- Aimé Bachelard (1885–1975) - A French magistrate, writer, and poet known by the pseudonym Aimé Sierroz, he concluded his career at the Grenoble Court of Appeal.[60]

- Gabriel-Marie Garrone (1901–1994) - A prominent church figure, he served as bishop of Chambéry and later as titular archbishop of Turres-en-Numidie, and was elevated to cardinal by Pope Paul VI.[61]

- Georges Brun (1922–1995) - A rugby player, he represented France as a fullback for the national team and played for CS Vienne.[62]

- Robert Bogey (1935–present) - A middle-distance runner, he was a four-time French champion in the 5,000 and 10,000 meters, and a national cross-country champion.[63]

- Jean Mailland (1937–2017) - A multifaceted talent, he is a writer, lyricist, actor, director, and theater producer.[64]

- Guy Bertin (1954–present) - A motorcycle speed rider, he is the only competitor to have won the Bol d'Or, the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and the Grand Prix de France, and he was the runner-up in the 1980 125 cm³ motorcycle championship.[65]

- Di Credico (1957–present) - A figurative painter known for his large-scale works created in real-time before an audience, often described as a Happening.[66]

- Agnès Soral (1960–present) - A French actress recognized for her role alongside Coluche in Claude Berri's 1983 film Tchao Pantin. She is also the sister of writer Alain Soral.[67]

- Karl Zéro (1961–present) - A French television presenter with a diverse career in television, radio, and print media, he is also known for directing satirical political films.[68]

- Thierry Tulasne (1963–present) - A former French tennis player, he boasts an impressive record in youth categories, including a world junior championship title.[69]

- Laurence Ferrari (1966–present) - A French journalist with experience in television (Canal+), radio, and print media, she is the daughter of former Aix-les-Bains mayor Gratien Ferrari.[70]

- Philippe Cerboneschi (1967–2019) - Known as Philippe Zdar, he is a member of the musical duo Cassius and a respected music producer.[71]

- Hervé Renard (1968–present) - A former professional footballer, he currently serves as an assistant coach for the Ghana national team under Claude Le Roy.[72]

- Philippe Cavoret (1968–present) - After competing in bobsleigh, he transitioned to skeleton, representing France at both the World Championships and the Olympic Games.[73]

- Soheil Ayari (1970–present) - A car driver specializing in endurance and Grand Touring races, he won the French Formula 3 championship and the Macau Grand Prix.[74]

Other personalities

[edit]List of non-Aixois personalities with ties to the city.

- Alphonse de Lamartine (1790–1869) - A prominent French poet who resided in Aix-en-Savoie in 1816, where he composed his famous poem Le lac. A recreation of his room can be viewed at the Musée Faure.[75]

- Henri Rochefort (1831–1913) - Born Victor Henri de Rochefort-Luçay in Paris, he was a noted French journalist and politician who spent his later years in Aix-les-Bains.[76]

- Alfred Boucher (1850–1934) - A sculptor who moved to Aix-les-Bains in 1889, he passed away there in 1934. He is known for creating the town's war memorial, located in a square named after him.[77]

- Jean-Baptiste Charcot: (1867–1936) - A notable figure who lived with his family in the Chalet Charcot, situated near the thermal baths of Aix-les-Bains.[78]

- Léon Brunschvicg (1869–1944) - A French philosopher associated with French idealism, he made significant contributions to academic thought during his lifetime.[79]

- Henri Ménabréa (1882–1968) - A lawyer, historian of Savoy, and librarian, he was active in numerous learned societies and served as president of the Académie de Savoie.[80]

- Marie de Solms (1831–1902) - A French poet and woman of letters known for her literary contributions.[81]

- Jean Longuet (1876–1938) - A French politician born in London, he was a significant member of the SFIO and passed away in Aix-les-Bains.[82]

- Jean Bretagne Charles de La Trémoille (1737–1792) - Born in Paris, he was the son of Charles Armand René de La Trémoille and Marie Hortense de La Tour d'Auvergne. He died in Aix-les-Bains.[83]

- Daniel-Rops (Henri Petiot) (1901–1965) - A French writer and historian, he was born in Épinal and spent his later years in Aix-les-Bains.[84]

- Alfred Charles Ernest Franquet de Franqueville (1809–1876) - A French engineer and Director General of Ponts et Chaussées and Railways from 1853 until his death in Aix-les-Bains.[85]

- Guy Husson (1935–present) - A French hammer thrower who won the French Hammer Championship 15 times consecutively.[86]

- Paul Arpin (1965–present) - A long-distance runner and member of AS Aix-les-Bains until 1990 and again from 1993 to 1995, he achieved multiple national and European championships in his discipline.[87]

- Ernest Munier-Chalmas (d. 1903) - A geologist known for his contributions to the study of the Cretaceous period, he was a member of the Académie des Sciences.[88]

- Georges Lorand (d. 1918) - A Belgian politician and Walloon activist, he was a lawyer, journalist, and political figure who also passed away in Aix-les-Bains.[89]

Numerous personalities have visited Aix-les-Bains for spa treatments, one of the most famous being Queen Victoria.[90] Others include Madame de Staël, Madame Récamier, Alexandre Dumas Père, Honoré de Balzac,[91] George Sand,[92] Marie de Solms,[93] Guy de Maupassant, Paul Verlaine, Puvis de Chavannes, Sarah Bernhardt, Saint-Saëns, Rachmaninov, Jean Moulin, Bergson, Edwige Feuillère, Claudel, Yvonne Printemps, and Pierre Fresnay.[94]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Lagrange, Joel (2007). Aix-les-Bains Tome 2 - l'Entre-Deux-Guerres. Alan Sutton. ISBN 978-2-84910-713-3.

- Frieh-Giraud, Geneviève (2005). Aix-les-Bains : Ville d'eaux de la Belle Époque. Dauphiné Libéré. ISBN 2-91173-986-8.

- Connille, Jean-François (2003). Aix-les-Bains. : Héritages & ouvertures. Questio. ISBN 2-91373-215-1.

- Fouger, François (2013). Le chemin de fer à Crémaillère Aix-les-Bains / Le Revard (2nd, revised. ed.). Oriade. ISBN 978-2-9519632-8-3.

- Jeudy, Jean-Marie (1998). Chambéry et Aix-les-bains autrefois. Horvath. ISBN 2-71710-920-X.

- Pallière, Johannès (1992). Aix les Bains à la belle époque, Histoire du capitalisme aixois : Ruptures, contrastes et résistances. La Fontaine de Siloé. p. 198. ISBN 978-2-908697-44-5.

- Pérouse, Gabriel (1967). La vie d'autrefois à Aix-les-bains la ville, les thermes, les baigneurs. Dardel. ASIN B0000DRAKF.

- Weigel, Anne; Ferrari, Gratien; Pallière, Johannès (1988). Ville des eaux, ville des rois : Histoire d'Aix-les-Bains, La Ville.

References

[edit]- ^ "Six nouveaux sites inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO" [Six new sites inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List]. UNESCO (in French). 2011-06-27. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Sites palafittiques préhistoriques autour des Alpes" [Prehistoric palaeolithic sites around the Alps]. UNESCO (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Roy, Philippe (2013). "Mithra et l'Apollon celtique en Gaule". Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni (in French). 79 (2): 360–378.

- ^ "Le dieu des sources thermales" [The god of hot springs]. Deshoulières François (in French). 81: 224. 1822.

- ^ Canal, Alain (1992). Rapport des fouilles en sauvetage sous la place Maurice Mollard.

- ^ Textes épigraphiques ; Musée lapidaire d'Aix-les-Bains.

- ^ Canal, Alain (1988). Fouilles du parking de l'Hôtel de ville.

- ^ "Accueil". patrimoine-aixlesbains.fr (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-02.

- ^ Pérouse, Gabriel (1922). La vie d'autrefois à Aix-les-Bains. Chambéry : Dardel.

- ^ Pernon, Christine. (1993). Études des vestiges de la maison forte de Saint Paul et prospection.

- ^ Legay, Jean Pierre. Connille Jean François. Histoire d'Aix-les-Bains et de sa région. Aix-les-Bains. imp. De l’Avenir.

- ^ Archives départementales de Savoie.

- ^ Lagrange, Joël (1998). Aix-les-Bains en 1561, aperçus démographiques. Aix-les-Bains. Extrait d'Art et Mémoire N°13.

- ^ Art et Mémoire n°15, la collégiale Notre Dame. 2000.

- ^ "Évolution du centre historique" [Development of the historic center] (PDF). Savoie Conseil General (in French). 2005.

- ^ Les Merveilles des bains d'Aix en Savoye (Réimpression textuelle de la première édition ed.). 1623.

- ^ Frieh-Giraud., Geneviève (2005). Les Thermes Nationaux d'Aix-les-Bains.

- ^ Sorrel, Christian (2013). "Deux « réunions » pour un destin français : la Savoie de 1792 à 1860" [Two “reunions” for a French destiny: Savoie from 1792 to 1860]. École nationale des chartes. Se donner à la France ? Les rattachements pacifiques de territoires à la France (XIVe-XIXe siècle) (in French): 105–121.

- ^ Brocard, Michèle. Les châteaux de Savoie.

- ^ Jeudy, Jean-Marie (1984). Chambéry et Aix-les-Bains autrefois. éd.Horvath. p. 38. ISBN 2-7171-0341-4.

- ^ Guichonnet, Paul (1960). Comment la Savoie se rallia à la France. éd. SIPE. p. 106.

- ^ "Commission départementale de l'information historique pour la paix (C.D.I.H.P.). Sous-commission coordination des cérémonies commémoratives". FranceArchives (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-04.

- ^ a b Arts et mémoire no 9. société d'Art et d'histoire d'Aix-les-Bains et de sa région. 1987.

- ^ Lagrange, Joel; Gras, Philippe (2017). "Les hôpitaux militaires pendant la Grande Guerre à Aix-les-Bains" [Military hospitals in Aix-les-Bains during the Great War]. In Situ [Online] (31).

- ^ a b c "Aix les Bains - Le casino Grand Cercle et la Grande Guerre" [Aix les Bains - The Grand Cercle casino and the Great War] (in French). 2018-11-12. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ "Aga Khan Marries Former Shopgirl". The New York Times. 1929. p. 3.

- ^ "Aga Khan Again a Father". The New York Times. 1933. p. 9.

- ^ "Laure Diebold-Mutschler". DNA. 2024-03-08. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ La vie d'autrefois à aix-les-bains.

- ^ Palluel-Guillard, André (1986). "La Savoie de la Révolution à nos jours, XIXe – XXe siècle". Histoire de la Savoie. IV. Ed. Ouest France: 255.

- ^ "ISAC ou IZAC Pierre". Elec. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ "18 - The great hall of the Thermes Pétriaux (1933)". Aix les Bains. Retrieved 2024-06-11.

- ^ "123 Savoie – Passionnés de Savoie depuis 2002 !". 123savoie.com. Retrieved 2024-09-04.

- ^ "Fès construira une fontaine à Aix-Les-Bains". bladinet (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-04.

- ^ Joly, Jean-Bernard (2021-04-13). "1876, Louis Mekarski présente son projet de Tramway à air comprimé". Les Horizons. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ Belle, Elsa; Gras, Philippe (2016). "De la montagne comme adjuvant à la cure au site de loisirs urbains : le Revard et Aix-les-Bains (xixe-xxe siècle)". Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques.

- ^ Verdicchio, Andrea (2019). "Nouvelle électrification en courant continu moyenne tension pour réseau ferroviaire" (PDF). UNIVERSITÉ DE TOULOUSE.

- ^ "Tour de France 2001". Le Tour. Archived from the original on 2004-05-03. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ "Year 1998". Le Tour. Archived from the original on 2020-04-03. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ "Aix-les-Bains dans le Tour de France depuis 1947". Le Dico du Tour. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ "1960 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ "1958 Tour de France". BikeRaceInfo. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ "Classique des Alpes(1.1)". PCS. Retrieved 2024-11-06.

- ^ "Fiche de FERNANDO MANZANEQUE". L'Équipe (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ "Guy HUSSON, France. Athletics Biography". Olympics.

- ^ "ATHLE.FR | Les 100 qui ont fait l'athlé français : Les rois du demi-fond". www.athle.fr (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ Solidus (2009-03-11). "Pancho Gonzales". Foro del tenis (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ "The day Laver won the calendar Grand Slam AGAIN!!". Tennis Majors. 2023-09-09. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ "All results - Raymond Ceulemans". www.raymondceulemans.com. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ "RICHARD CHELIMO". Le Monde. 2001-10-19. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "ATHLETISME : championnats du monde de cross-country Skah triomphe des Kenyans" [ATHLETICS: Skah cross-country world championships triumphs over Kenyans]. Le Monde (in French). 1990-03-27. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "PAUL KIPKOECH, Kenya". Caaweb. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Grégory GABELLA | Profile | World Athletics". worldathletics.org. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ "Saison 2006-2007" [2006-2007 season]. Histoire du PSG (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "ÉCHECS : Etienne Bacrot champion de France" [CHESS: Etienne Bacrot French Champion]. Le Monde (in French). 2003-09-03. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "16-year-old Vachier-Lagrave new French Champion". Chess News. 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ a b Mullié, Charles (1852). Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 à 1850.

- ^ "Jean-Claude-Nicolas Forestier". Portraits d'architectes. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Dufour, Philippe (2023-10-05). "Jean de Sperati ou le roman d'un faussaire en timbres" [Jean de Sperati or the story of a stamp forger]. Gazette Drout (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Membres titulaires de l'Académie Delphinale depuis 1906" (PDF). Académie Delphinale. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Ancien archevêque de Toulouse et prélat de la Curie romaine Le cardinal Garrone est mort" [Former archbishop of Toulouse and prelate of the Roman Curia Cardinal Garrone has died]. Le Monde (in French). 1994-01-18. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Georges Brun". Equipe-France.fr. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Pallandre, Christian (2014-10-22). "Aix – les – Bains : Rencontres avec Robert Bogey" [Aix - les - Bains: Meetings with Robert Bogey]. Asphalte 94 (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Héliot, Armelle (2017-05-12). "Adieu à Jean Mailland, homme de paroles" [Farewell to Jean Mailland, man of words]. Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Martet, Florine (2013-04-23). "Pilote de légende : Guy Bertin" [Pilote de légende : Guy Bertin]. Le Repaire (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Tricoche, Patricia (2019-04-26). "Robert Di Credico : figuratif et flamboyant" [Robert Di Credico: figurative and flamboyant]. Essor Isere (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Guyard, Bertrand. "Agnès Soral : «Pendant Tchao Pantin, Coluche souffrait»" [Agnès Soral: “During Tchao Pantin, Coluche suffered”.]. Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Karl Zéro". Purepeople. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Thierry Tulasne rêve d'un " retour gagnant " à Tours" [Thierry Tulasne dreams of a “winning return” to Tours]. La Nouvelle Republique (in French). 2014-07-17. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Laurence Ferrari". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Mort accidentelle à 50 ans de Philippe «Zdar» du duo électro Cassius" [Accidental death at 50 of Philippe “Zdar” of electro duo Cassius]. Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Double vainqueur de la CAN, ancien chef d'entreprise, adepte de la chemise blanche... cinq choses à savoir sur Hervé Renard, le nouveau sélectionneur des Bleues" [Two-time Africa Cup of Nations winner, former company director, white shirt enthusiast... five things you need to know about Hervé Renard, the new coach of Les Bleues.]. DNA (in French). 2023-03-30. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Di Meo, Dino (2022-02-20). "«Un truc à sensations»" ["A thrill ride"]. Liberation (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Lecouturier, Benjamin (2024-03-14). "Soheil Ayari : « Les 24 Heures du Mans, c'est un moment à part »" [Soheil Ayari: “The 24 Hours of Le Mans is a special moment”.]. La Vie Nouvelle. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Lamartine, le poète du lac et de la région aixoise" [Lamartine, the poet of the lake and the Aix region]. Le Dauphine (in French). 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Henri Rochefort (1831 - 1913)". Herodote. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Lagrange, Joel (2014). "Le monument aux morts d'Aix-les-Bains. Une œuvre d'Alfred Boucher" [The Aix-les-Bains war memorial. A work by Alfred Boucher]. Monuments commémoratifs (in French) (25).

- ^ "Jean-Baptiste Charcot, histoire d'un explorateur hors-normes" [Jean-Baptiste Charcot, the story of an extraordinary explorer]. Le Magazine (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Brunschvicg, Léon (1869-1944)". Imec. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "MENABREA Henri". CTHS. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Un roman dans mon jardin – Poème de Marie de Solms" [Un roman dans mon jardin - Poem by Marie de Solms]. Poussière Virtuelle (in French). 2010-04-19. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "LONGUET Jean [LONGUET Frédéric, Jean, Laurent]". Maitron. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "de La Trémoille Jean Bretagne Charles". Canal Blog. 2016-08-05. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Henri PETIOT, dit DANIEL-ROPS" [Henri PETIOT, known as DANIEL-ROPS]. Acadèmie française (in German). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Alfred Charles Ernest FRANQUET de FRANQUEVILLE (1809-1876)". Annales. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Massait, Aurèlie (2023-01-14). ""C'est une force de la nature" : à 92 ans, le légendaire lanceur de marteau Guy Husson reçoit la médaille de la reconnaissance" [“He's a force of nature”: at 92, legendary hammer thrower Guy Husson receives the Medal of Recognition]. France 3 (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "La course du solitaire" [The solo race]. Le Monde. 1987-02-28. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Munier-Chalmas, Ernest (1843-1903)". Persee. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ Genin, Vincent (2018). "Déconstruire l'image de la Belgique «germanophile» à l'Étranger (1915-1916) -Propagande et relations internationales. Quatorze lettres et notes inédites d'Eugène Beyens, Paul Hymans et Georges Lorand" [Deconstructing the image of “Germanophile” Belgium abroad (1915-1916) -Propaganda and international relations. Fourteen unpublished letters and notes by Eugène Beyens, Paul Hymans and Georges Lorand]. Bulletin de la Commission royale d'Histoire (in German) (184): 223–268.

- ^ Jung, Laurence (2020-05-20). "Aix-les-Bains, « la reine des séjours et le séjour des reines »" [Aix-les-Bains, “the queen of stays and the stay of queens”.]. Gallica. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ In 1831, Balzac's “La peau de chagrin” (1831) set part of the plot in Aix. The following year, he wrote Le médecin de campagne. in André Palluel-Guillard, Sorrel (C), Fleury (A), Loup (J), La Savoie de la Révolution à nos jours, XIXe - XXe siècle, 1986, Tome IV, coll. Histoire de la Savoie, Leguay (JP (sous la dir.), Ed. Ouest France, p. 229

- ^ George Sand came to Aix to visit her friend François Buloz, co-founder of the Revue des deux Mondes, and in 1863 published a novel set in Aix, Mademoiselle La Quintinie, in André Palluel-Guillard, Sorrel (C), Fleury (A), Loup (J), La Savoie de la Révolution à nos jours, XIXe - XXe siècle, 1986, Tome IV, coll. Histoire de la Savoie, Leguay (JP (sous la dir.), Ed. Ouest France, p. 229.

- ^ Marie de Solms wrote the “Matinées d'Aix-les-Bains”, in André Palluel-Guillard, Sorrel (C), Fleury (A), Loup (J), La Savoie de la Révolution à nos jours, XIXe - XXe siècle, 1986, Tome IV, coll. Histoire de la Savoie, Leguay (JP (sous la dir.), Ed. Ouest France , p. 229

- ^ "Personnalités". Aix les Bains (in French). Retrieved 2024-10-30.