Mobile, Alabama

Mobile | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nickname(s): "The Port City", "Azalea City", "The City of Six Flags" | |

Interactive map of Mobile | |

| Coordinates: 30°40′03″N 88°06′04″W / 30.66750°N 88.10111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Mobile |

| Founded | 1702 |

| Incorporated (town) | January 20, 1814[1][2] |

| Incorporated (city) | December 17, 1819[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Sandy Stimpson (R[4]) |

| • City Council | District 1 – Cory Penn District 2 – William Carroll District 3 – C.J. Small District 4 – Ben Reynolds District 5 – Joel Daves District 6 – Josh Woods District 7 – Gina Gregory |

| Area | |

• City | 180.07 sq mi (466.39 km2) |

| • Land | 139.48 sq mi (361.26 km2) |

| • Water | 40.59 sq mi (105.14 km2) |

| • Urban | 220.75 sq mi (571.7 km2) |

| • Metro | 1,229 sq mi (3,184 km2) |

| Elevation | 33 ft (10 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 187,041 |

• Estimate (2022)[9] | 183,289 |

| • Rank | US: 141st AL: 4th |

| • Density | 1,314/sq mi (507.4/km2) |

| • Urban | 321,907 (US: 126th)[6] |

| • Urban density | 1,458.3/sq mi (563.0/km2) |

| • Metro | 411,640 (US: 133rd) |

| • Metro density | 335/sq mi (129.2/km2) |

| • Combined | 665,147 (US: 79th) |

| • Combined density | 172.6/sq mi (66.63/km2) |

| Demonym | Mobilian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | Zip codes[10] |

| Area code | 251 |

| FIPS code | 01-50000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2404278[7] |

| Website | cityofmobile.org |

Mobile (/moʊˈbiːl/ moh-BEEL, French: [mɔbil] ⓘ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population was 187,041 at the 2020 census.[8][9] After a successful vote to annex areas west of the city limits in July 2023, Mobile's population increased to 204,689 residents, making it the fourth-most populous city in Alabama, after Montgomery, Birmingham, and Huntsville.[11] Mobile is the principal municipality of the Mobile metropolitan area, a region of 430,197 residents composed of Mobile and Washington counties; it is the third-largest metropolitan area in the state after Birmingham and Huntsville.[12]

Alabama's only saltwater port, Mobile is located on the Mobile River at the head of Mobile Bay on the north-central Gulf Coast.[13] The Port of Mobile has always played a key role in the economic health of the city, beginning with the settlement as an important trading center between the French colonists and Native Americans, down to its current role as the 12th-largest port in the United States.[14][15]

Mobile was founded in 1702 by the French as the first capital of Louisiana. During its first 100 years, Mobile was a colony of France, then Great Britain, and lastly Spain. Mobile became a part of the United States in 1813, with the annexation by President James Madison of West Florida from Spain.[16] During the American Civil War, the city surrendered to Federal forces on April 12, 1865,[17] after Union victories at two forts protecting the city. This, along with the news of Johnston's surrender negotiations with Sherman, led General Richard Taylor to seek a meeting with his Union counterpart, Maj. Gen. Edward R. S. Canby. The two generals met several miles north of Mobile on May 2. After agreeing to a 48-hour truce, the generals enjoyed an al fresco luncheon of food, drink, and lively music. Canby offered Taylor the same terms agreed upon between Lee and Grant at Appomattox. Taylor accepted the terms and surrendered his command on May 4 at Citronelle, Alabama.[18]

Considered one of the Gulf Coast's cultural centers, Mobile has several art museums, a symphony orchestra, professional opera, professional ballet company, and a large concentration of historic architecture.[19][20] Mobile is known for having the oldest organized Carnival or Mardi Gras celebrations in the United States. Alabama's French Creole population celebrated this festival from the first decade of the 18th century. Beginning in 1830, Mobile was host to the first formally organized Carnival mystic society to celebrate with a parade in the United States. (In New Orleans, such a group is called a krewe.)[21]

Etymology

The city gained its name from the Mobile tribe that the French colonists encountered living in the area of Mobile Bay.[22] Although it is debated by Alabama historians, they may have been descendants of the Native American tribe whose small fortress town, Mabila, was used to conceal several thousand native warriors before an attack in 1540 on the expedition of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto.[23] About seven years after the founding of the French Mobile settlement, the Mobile tribe, along with the Tohomé, gained permission from the colonists to settle near the fort.[24][25]

History

Colonial

The European settlement of Mobile began with French colonists, who in 1702 constructed Fort Louis de la Louisiane, at Twenty-seven Mile Bluff on the Mobile River, as the first capital of the French colony of La Louisiane. It was founded by French Canadian brothers Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, to establish control over France's claims to La Louisiane. Bienville was appointed as royal governor of French Louisiana in 1701. Mobile's Roman Catholic parish was established on July 20, 1703, by Jean-Baptiste de la Croix de Chevrières de Saint-Vallier, Bishop of Quebec.[26] The parish was the first French Catholic parish established on the Gulf Coast of the United States.[26]

In 1704, the ship Pélican delivered 23 Frenchwomen to the colony; passengers had contracted yellow fever at a stop in Havana.[27] Though most of the "Pélican girls" recovered, numerous colonists and neighboring Native Americans contracted the disease in turn and many died.[27] This early period was also the occasion of the importation of the first African slaves, transported aboard a French supply ship from the French colony of Saint-Domingue in the Caribbean, where they had first been held.[27] The population of the colony fluctuated over the next few years, growing to 279 persons by 1708, yet shrinking to 178 persons two years later due to disease.[26]

These additional outbreaks of disease and a series of floods resulted in Bienville ordering in 1711 that the settlement be relocated several miles downriver to its present location at the confluence of the Mobile River and Mobile Bay.[28] A new earth-and-palisade Fort Louis was constructed at the new site during this time.[29] By 1712, when Antoine Crozat was appointed to take over administration of the colony, its population had reached 400 persons.[citation needed]

The capital of La Louisiane was moved in 1720 to Biloxi,[29] leaving Mobile to serve as a regional military and trading center. In 1723 the construction of a new brick fort with a stone foundation began[29] and it was renamed Fort Condé in honor of Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon.[30]

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the Seven Years' War, which Britain won, defeating France. By this treaty, France ceded its territories east of the Mississippi River to Britain. This area was made a part of the expanded British West Florida colony.[31] The British changed the name of Fort Condé to Fort Charlotte, after Queen Charlotte.[32]

The British were eager not to lose any useful inhabitants and promised religious tolerance to the French colonists; ultimately 112 French colonists remained in Mobile.[33] The first permanent Jewish settlers came to Mobile in 1763 as a result of the new British rule and religious tolerance. Jews had not been allowed to officially reside in colonial French Louisiana due to the Code Noir, a decree passed by France's King Louis XIV in 1685 that forbade the exercise of any religion other than Roman Catholicism, and ordered all Jews out of France's colonies. Most of these colonial-era Jews in Mobile were merchants and traders from Sephardic Jewish communities in Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, South Carolina; they added to the commercial development of Mobile.[34] In 1766 the total population was estimated to be 860, though the town's borders were smaller than during the French colonial period.[33] During the American Revolutionary War, West Florida and Mobile became a refuge for loyalists fleeing the other colonies.[35]

While the British were dealing with their rebellious colonists along the Atlantic coast, the Spanish entered the war in 1779 as an ally of France. They took the opportunity to order Bernardo de Galvez, Governor of Louisiana, on an expedition east to retake West Florida.[36] He captured Mobile during the Battle of Fort Charlotte in 1780, as part of this campaign. The Spanish wished to eliminate any British threat to their Louisiana colony west of the Mississippi River, which they had received from France in the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[35] Their actions were condoned by the revolting American colonies, partially evidenced by the presence of Oliver Pollack, representative of the American Continental Congress. Due to strong trade ties, many residents of Mobile and West Florida remained loyal to the British Crown.[35][36] The Spanish renamed the fort as Fortaleza Carlota, and held Mobile as a part of Spanish West Florida until 1813, when it was seized by United States General James Wilkinson during the War of 1812.[37]

19th century

By the time Mobile was included in the Mississippi Territory in 1813, the population had dwindled to roughly 300 people.[38] The city was included in the Alabama Territory in 1817, after Mississippi gained statehood. Alabama was granted statehood in 1819; Mobile's population had increased to 809 by that time.[38]

Mobile was well situated for trade, as its location tied it to a river system that served as the principal navigational access for most of Alabama and a large part of Mississippi. River transportation was aided by the introduction of steamboats in the early decades of the 19th century.[39] By 1822, the city's population had risen to 2,800.[38]

The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain created shortages of cotton, driving up prices on world markets.[40] Much land well suited to growing cotton lies in the vicinity of the Mobile River, and its main tributaries the Tombigbee and Alabama Rivers. A plantation economy using slave labor developed in the region and as a consequence Mobile's population quickly grew. It came to be settled by attorneys, cotton factors, doctors, merchants and other professionals seeking to capitalize on trade with the upriver areas.[38]

From the 1830s onward, Mobile expanded into a city of commerce with a primary focus on the cotton and slave trades. Many slaves were transported by ship in the coastwise slave trade from the Upper South. There were many businesses in the city related to the slave trade – people to make clothes, food, and supplies for the slave traders and their wards. The city's booming businesses attracted merchants from the North; by 1850 10% of its population was from New York City, which was deeply involved in the cotton industry.[41] Mobile was the slave-trading center of the state until the 1850s, when it was surpassed by Montgomery.[42]

The prosperity stimulated a building boom that was underway by the mid-1830s, with the building of some of the most elaborate structures the city had seen up to that point. This was cut short in part by the Panic of 1837 and yellow fever epidemics.[43] The waterfront was developed with wharves, terminal facilities, and fireproof brick warehouses.[38] The exports of cotton grew in proportion to the amounts being produced in the Black Belt; by 1840 Mobile was second only to New Orleans in cotton exports in the nation.[38]

With the economy so focused on one crop, Mobile's fortunes were always tied to those of cotton, and the city weathered many financial crises.[38] Mobile slaveholders owned relatively few slaves compared to planters in the upland plantation areas, but many households had domestic slaves, and many other slaves worked on the waterfront and on riverboats. The last slaves to enter the United States from the African trade were brought to Mobile on the slave ship Clotilda. Among them was Cudjoe Lewis, who in the 1920s became the last survivor of the slave trade.[44]

By 1853, fifty Jewish families lived in Mobile, including Philip Phillips, an attorney from Charleston, South Carolina, who was elected to the Alabama State Legislature and then to the United States Congress. Many early Jewish families were descendants of Sephardic Jews who had been among the earliest colonial settlers in Charleston and Savannah.[45]

By 1860 Mobile's population within the city limits had reached 29,258 people; it was the 27th-largest city in the United States and 4th-largest in what would soon be the Confederate States of America.[46] The free population in the whole of Mobile County, including the city, consisted of 29,754 citizens, of which 1,195 were free people of color.[47] Additionally, 1,785 slave owners in the county held 11,376 people in bondage, about one-quarter of the total county population of 41,130 people.[47]

During the American Civil War, Mobile was a Confederate city. The H. L. Hunley, the first submarine to sink an enemy ship, was built in Mobile.[48] One of the most famous naval engagements of the war was the Battle of Mobile Bay, resulting in the Union taking control of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864.[49] On April 12, 1865, three days after Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, the city surrendered to the Union army to avoid destruction after Union victories at nearby Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley.[49]

On May 25, 1865, the city suffered great loss when some three hundred people died as a result of an explosion at a federal ammunition depot on Beauregard Street. The explosion left a 30-foot (9 m) deep hole at the depot's location, and sank ships docked on the Mobile River; the resulting fires destroyed the northern portion of the city.[50]

Federal Reconstruction in Mobile began after the Civil War and effectively ended in 1874 when the local Democrats gained control of the city government.[51] The last quarter of the 19th century was a time of economic depression and municipal insolvency for Mobile. One example can be provided by the value of Mobile's exports during this period of depression. The value of exports leaving the city fell from $9 million in 1878 to $3 million in 1882.[52]

20th century

The turn of the 20th century brought the Progressive Era to Mobile. The economic structure developed with new industries, generating new jobs and attracting a significant increase in population.[53] The population increased from around 40,000 in 1900 to 60,000 by 1920.[53] During this time the city received $3 million in federal grants for harbor improvements to deepen the shipping channels.[53] During and after World War I, manufacturing became increasingly vital to Mobile's economic health, with shipbuilding and steel production being two of the most important industries.[53]

During this time, social justice and race relations in Mobile worsened, however.[53] The state passed a new constitution in 1901 that disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites; and the white Democratic-dominated legislature passed other discriminatory legislation. In 1902, the city government passed Mobile's first racial segregation ordinance, segregating the city streetcars. It legislated what had been informal practice, enforced by convention.[53] Mobile's African-American population responded to this with a two-month boycott, but the law was not repealed.[53] After this, Mobile's de facto segregation was increasingly replaced with legislated segregation as whites imposed Jim Crow laws to maintain supremacy.[53]

In 1911 the city adopted a commission form of government, which had three members elected by at-large voting. Considered to be progressive, as it would reduce the power of ward bosses, this change resulted in the elite white majority strengthening its power, as only the majority could gain election of at-large candidates. In addition, poor whites and blacks had already been disenfranchised. Mobile was one of the last cities to retain this form of government, which prevented smaller groups from electing candidates of their choice. But Alabama's white yeomanry had historically favored single-member districts in order to elect candidates of their choice.[54]

The red imported fire ant was first introduced into the United States via the Port of Mobile. Sometime in the late 1930s they came ashore off cargo ships arriving from South America. The ants were carried in the soil used as ballast on those ships.[55] They have spread throughout the South and Southwest.

During World War II, the defense buildup in Mobile shipyards resulted in a considerable increase in the city's white middle-class and working-class population, largely due to the massive influx of workers coming to work in the shipyards and at the Brookley Army Air Field.[56] Between 1940 and 1943, more than 89,000 people moved into Mobile to work for war effort industries.[56]

Mobile was one of eighteen United States cities producing Liberty ships. Its Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO) supported the war effort by producing ships faster than the Axis powers could sink them. ADDSCO also churned out a copious number of T2 tankers for the War Department.[56] Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation, a subsidiary of Waterman Steamship Corporation, focused on building freighters, Fletcher-class destroyers, and minesweepers.[56] The rapid increase of population in the city produced crowded conditions, increasing social tensions in the competition for housing and good jobs.[57]

In May 1943, a race riot broke out between whites and blacks. ADDSCO management had long maintained segregated conditions at the shipyards, although the Roosevelt administration had ordered defense contractors to integrate facilities. That year ADDSCO promoted 12 blacks to positions as welders, previously reserved for whites; and whites objected to the change by rioting on May 24. The mayor appealed to the governor to call in the National Guard to restore order, but it was weeks before officials allowed African Americans to return to work,[58] keeping them away for their safety.[citation needed]

In the late 1940s, the transition to the postwar economy was hard for the city, as thousands of jobs were lost at the shipyards with the decline in the defense industry. Eventually the city's social structure began to become more liberal. Replacing shipbuilding as a primary economic force, the paper and chemical industries began to expand. No longer needed for defense, most of the old military bases were converted to civilian uses. Following the war, in which many African Americans had served, veterans and their supporters stepped up activism to gain enforcement of their constitutional rights and social justice, especially in the Jim Crow South. During the 1950s the City of Mobile integrated its police force and Spring Hill College accepted students of all races. Unlike in the rest of the state, by the early 1960s the city buses and lunch counters voluntarily desegregated.[56]

The Alabama legislature passed the Cater Act in 1949, allowing cities and counties to set up industrial development boards (IDB) to issue municipal bonds as incentives to attract new industry into their local areas. The city of Mobile did not establish a Cater Act board until 1962. George E. McNally, Mobile's first Republican mayor since Reconstruction, was the driving force behind the founding of the IDB. The Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce, believing its members were better qualified to attract new businesses and industry to the area, considered the new IDB as a serious rival. After several years of political squabbling, the Chamber of Commerce emerged victorious. While McNally's IDB prompted the Chamber of Commerce to become more proactive in attracting new industry, the chamber effectively shut Mobile city government out of economic development decisions.[59]

In 1963, three African-American students brought a case against the Mobile County School Board for being denied admission to Murphy High School.[60] This was nearly a decade after the United States Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. The federal district court ordered that the three students be admitted to Murphy for the 1964 school year, leading to the desegregation of Mobile County's school system.[60]

The civil rights movement gained congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, eventually ending legal segregation and regaining effective suffrage for African Americans. But whites in the state had more than one way to reduce African Americans' voting power. Maintaining the city commission form of government with at-large voting resulted in all positions being elected by the white majority, as African Americans could not command a majority for their candidates in the informally segregated city.[citation needed]

In 1969, the Brookley Air Force Base was closed by the Department of Defense, dealing a severe blow to Mobile's economy. The closing resulted in a 10% unemployment rate in the city. This and other factors related to industrial restructuring ushered in a period of economic depression that lasted through the 1970s. The loss of jobs created numerous problems and resulted in loss of population as residents moved away for work.[citation needed]

Mobile's city commission form of government was challenged and finally overturned in 1982 in City of Mobile v. Bolden, which was remanded by the United States Supreme Court to the district court. Finding that the city had adopted a commission form of government in 1911 and at-large positions with discriminatory intent, the court proposed that the three members of the city commission should be elected from single-member districts, likely ending their division of executive functions among them. Mobile's state legislative delegation in 1985 finally enacted a mayor-council form of government, with seven members elected from single-member districts. This was approved by voters.[54] As white conservatives increasingly entered the Republican Party in the late 20th century, African-American residents of the city have elected members of the Democratic Party as their candidates of choice. Since the change to single-member districts, more women and African Americans were elected to the council than under the at-large system.[54]

Beginning in the late 1980s, newly elected mayor Mike Dow and the city council began an effort termed the "String of Pearls Initiative" to make Mobile into a competitive city.[61] The city initiated construction of numerous new facilities and projects, and the restoration of hundreds of historic downtown buildings and homes.[61] City and county leaders also made efforts to attract new business ventures to the area.[62]

Geography and climate

Geography

Mobile is located in the southwestern part of the U.S. state of Alabama.[63] It is 168 miles (270 km) by highway southwest of Montgomery, the state capital; 58 miles (93 km) west of Pensacola, Florida; and 144 miles (232 km) northeast of New Orleans.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 180.07 square miles (466.4 km2), with 139.48 square miles (361.3 km2) of it being land, and 40.59 square miles (105.1 km2), or 22.5% of the total, being covered by water.[5] The elevation in Mobile ranges from 10 feet (3 m) on Water Street in downtown[7] to 211 feet (64 m) at the Mobile Regional Airport.[64]

Neighborhoods

Mobile has a number of notable historic neighborhoods. These include Ashland Place, Campground, Church Street East, De Tonti Square, Leinkauf, Lower Dauphin Street, Midtown, Oakleigh Garden, Old Dauphin Way, Spring Hill, and Toulminville.[65][66][67]

Climate

| Mobile | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mobile's geographical location on the Gulf of Mexico provides a mild subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with hot, humid summers and mild, rainy winters. The record low temperature was −1 °F (−18 °C), set on February 13, 1899, and the record high was 105 °F (41 °C), set on August 29, 2000.[68][69]

A 2007 study by WeatherBill, Inc. determined that Mobile is the wettest city in the contiguous 48 states, with 66.3 inches (1,680 mm) of average annual rainfall over a 30-year period.[70] Mobile averages 120 days per year with at least 0.01 inches (0.3 mm) of rain. Precipitation is heavy year-round. On average, July and August are the wettest months, with frequent and often-heavy shower and thunderstorm activity. October stands out as a slightly drier month than all others. Snow is rare in Mobile, with its last snowfall occurring on December 8, 2017;[71] before this, the last snowfall had been nearly four years earlier, on January 27, 2014.[72]

Mobile is occasionally affected by major tropical storms and hurricanes.[20] The city suffered a major natural disaster on the night of September 12, 1979, when category-3 Hurricane Frederic passed over the heart of the city. The storm caused tremendous damage to Mobile and the surrounding area.[73] Mobile had moderate damage from Hurricane Opal on October 4, 1995, and Hurricane Ivan on September 16, 2004.[74]

Mobile suffered millions of dollars in damage from Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, which damaged much of the Gulf Coast cities. A storm surge of 11.45 feet (3.49 m), topped by higher waves, damaged eastern sections of the city with extensive flooding in downtown, the Battleship Parkway, and the elevated Jubilee Parkway.[75]

| Climate data for Mobile, Alabama (Mobile Regional Airport, 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1872–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

85 (29) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 75.7 (24.3) |

77.6 (25.3) |

83.0 (28.3) |

86.3 (30.2) |

92.2 (33.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

96.7 (35.9) |

96.2 (35.7) |

93.8 (34.3) |

89.1 (31.7) |

82.0 (27.8) |

77.6 (25.3) |

97.8 (36.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 61.5 (16.4) |

65.6 (18.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

77.8 (25.4) |

84.9 (29.4) |

89.4 (31.9) |

90.9 (32.7) |

90.8 (32.7) |

87.5 (30.8) |

79.7 (26.5) |

70.2 (21.2) |

63.5 (17.5) |

77.8 (25.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.1 (10.6) |

55.0 (12.8) |

60.9 (16.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

74.4 (23.6) |

80.1 (26.7) |

82.0 (27.8) |

81.9 (27.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

69.0 (20.6) |

58.9 (14.9) |

53.3 (11.8) |

67.6 (19.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 40.7 (4.8) |

44.4 (6.9) |

50.0 (10.0) |

56.0 (13.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

73.1 (22.8) |

72.9 (22.7) |

68.8 (20.4) |

58.2 (14.6) |

47.7 (8.7) |

43.0 (6.1) |

57.4 (14.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 22.7 (−5.2) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

40.0 (4.4) |

50.0 (10.0) |

63.2 (17.3) |

68.6 (20.3) |

67.3 (19.6) |

56.8 (13.8) |

40.5 (4.7) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 3 (−16) |

−1 (−18) |

21 (−6) |

32 (0) |

43 (6) |

49 (9) |

62 (17) |

57 (14) |

42 (6) |

30 (−1) |

22 (−6) |

8 (−13) |

−1 (−18) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.66 (144) |

4.47 (114) |

5.44 (138) |

5.71 (145) |

5.39 (137) |

6.55 (166) |

7.69 (195) |

6.87 (174) |

5.30 (135) |

3.95 (100) |

4.60 (117) |

5.45 (138) |

67.08 (1,704) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 12.4 | 14.9 | 13.2 | 9.2 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 9.4 | 117.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 72 | 72 | 71 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 78 | 77 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 158 | 155 | 211 | 255 | 300 | 287 | 246 | 254 | 233 | 254 | 193 | 145 | 2,691 |

| Source 1: NOAA (humidity 1981–2010)[76][77][78][79] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (sun, 1931–1960)[80] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mobile, Alabama (Mobile Downtown Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1948–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

86 (30) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

99 (37) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

82 (28) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 74.5 (23.6) |

76.8 (24.9) |

81.5 (27.5) |

85.1 (29.5) |

92.2 (33.4) |

95.2 (35.1) |

96.7 (35.9) |

96.2 (35.7) |

94.2 (34.6) |

89.1 (31.7) |

82.4 (28.0) |

76.7 (24.8) |

97.8 (36.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 62.1 (16.7) |

65.8 (18.8) |

71.8 (22.1) |

77.9 (25.5) |

85.0 (29.4) |

90.0 (32.2) |

91.7 (33.2) |

91.9 (33.3) |

88.8 (31.6) |

81.3 (27.4) |

71.6 (22.0) |

64.3 (17.9) |

78.5 (25.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 52.3 (11.3) |

55.9 (13.3) |

61.8 (16.6) |

68.3 (20.2) |

75.7 (24.3) |

81.5 (27.5) |

83.5 (28.6) |

83.6 (28.7) |

80.3 (26.8) |

71.1 (21.7) |

60.8 (16.0) |

54.6 (12.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 42.5 (5.8) |

46.1 (7.8) |

51.8 (11.0) |

58.6 (14.8) |

66.3 (19.1) |

73.1 (22.8) |

75.3 (24.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

71.8 (22.1) |

61.0 (16.1) |

49.9 (9.9) |

44.9 (7.2) |

59.7 (15.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 24.0 (−4.4) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

34.1 (1.2) |

42.5 (5.8) |

51.7 (10.9) |

65.6 (18.7) |

69.9 (21.1) |

68.5 (20.3) |

59.1 (15.1) |

43.3 (6.3) |

32.7 (0.4) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 8 (−13) |

13 (−11) |

23 (−5) |

36 (2) |

43 (6) |

55 (13) |

63 (17) |

60 (16) |

48 (9) |

34 (1) |

24 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

8 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.19 (132) |

3.77 (96) |

5.11 (130) |

4.86 (123) |

4.42 (112) |

5.78 (147) |

6.57 (167) |

7.14 (181) |

4.47 (114) |

3.80 (97) |

4.13 (105) |

5.28 (134) |

60.52 (1,537) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.3 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 12.7 | 14.4 | 14.0 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 133.4 |

| Source: NOAA[76][81] | |||||||||||||

Christmas Day tornado

In late December 2012, the city suffered two tornado hits.[clarification needed] On December 25, 2012, at 4:54 pm, a large wedge tornado touched down in the city.[82] The tornado rapidly intensified as it moved north-northeast at speeds of up to 50 mph (80 km/h). The path took the tornado into Midtown, causing damage or destruction to at least 100 structures. The heaviest damage to houses was along Carlen Street, Rickarby Place, Dauphin Street, Old Shell Road, Margaret Street, Silverwood Street, and Springhill Avenue.[82]

The tornado caused significant damage to the Carmelite Monastery, Little Flower Catholic Church, commercial real estate along Airport Boulevard and Government Street in the Midtown at the Loop neighborhood, Murphy High School, Trinity Episcopal Church, Springhill Avenue Temple, and Mobile Infirmary Hospital before moving into the neighboring city of Prichard.[82] The tornado was classified as an EF2 tornado by the National Weather Service on December 26.[82]

The path taken through the city was just a short distance east of the path taken days earlier, on December 20, by an EF1 tornado which had touched down near Davidson High School and taken a path ending in Prichard.[83] Initial damage estimates for insured and uninsured ranged from $140 to $150 million.

Culture

Mobile's French and Spanish colonial history has given it a culture distinguished by French, Spanish, Creole, African and Catholic heritage, in addition to later British and American influences. It is distinguished from all other cities in the state of Alabama. The annual Carnival celebration is perhaps the best example of its differences. Mobile is the birthplace of the celebration of Mardi Gras in the United States and has the oldest celebration, dating to the early 18th century during the French colonial period.[84]

Carnival in Mobile evolved over the course of 300 years from a beginning as a sedate French Catholic tradition into the mainstream multi-week celebration that today bridges a spectrum of cultures.[85] Mobile's official cultural ambassadors are the Azalea Trail Maids, meant to embody the ideals of Southern hospitality.[86]

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Back Roads (1981) were shot in Mobile.[87]

Carnival and Mardi Gras

The Carnival season has expanded throughout the late fall and winter: balls in the city may be scheduled as early as November, with the parades beginning after January 5 and the Twelfth Day of Christmas or Epiphany on January 6.[88][89] Carnival celebrations end at midnight on Mardi Gras, a moveable feast related to the timing of Lent and Easter. The next day is Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent, the 40-day penitential season before Easter.[90]

In Mobile, locals often use the term Mardi Gras as a shorthand to refer to the entire Carnival season. During the Carnival season; the mystic societies build colorful floats and parade throughout downtown. Masked society members toss small gifts, known as 'throws,' to parade spectators.[91] The mystic societies, which in essence are exclusive private clubs, also hold formal masquerade balls, usually by invitation only, and oriented to adults.[89]

Carnival was first celebrated in Mobile in 1703 when colonial French Catholic settlers carried out their traditional celebration at the Old Mobile Site, prior to the 1711 relocation of the city to the current site.[21] Mobile's first Carnival society was established in 1711 with the Boeuf Gras Society (Fatted Ox Society).[92] Celebrations were relatively small and consisted of local, private parties until the early 19th century.[citation needed]

In 1830 Mobile's Cowbellion de Rakin Society was the first formally organized and masked mystic society in the United States to celebrate with a parade.[21][90] The Cowbellions got their start when Michael Krafft, a cotton factor from Pennsylvania, began a parade with rakes, hoes, and cowbells.[90] The Cowbellians introduced horse-drawn floats to the parades in 1840 with a parade entitled "Heathen Gods and Goddesses".[92] The Striker's Independent Society, formed in 1843, is the oldest surviving mystic society in the United States.[92]

Carnival celebrations in Mobile were canceled during the American Civil War. In 1866 Joe Cain revived the Mardi Gras parades when he paraded through the city streets on Fat Tuesday while costumed as a fictional Chickasaw chief named Slacabamorinico. He celebrated the day in front of the occupying Union Army troops.[93] In 2002, Mobile's Tricentennial celebrated with parades that represented all of the city's mystic societies.[92]

Founded in 2004, the Conde Explorers in 2005 were the first integrated Mardi Gras society to parade in downtown Mobile. The society has about a hundred members and welcomes men and women of all races. In addition to the parade and ball, the Conde Explorers hold several parties throughout the year. Its members also perform volunteer work. The Conde Explorers were featured in the award-winning documentary, The Order of Myths (2008), by Margaret Brown about Mobile's Mardi Gras.[94][95]

Archives and libraries

The National African American Archives and Museum features the history of African-American participation in Mardi Gras, authentic artifacts from the era of slavery, and portraits and biographies of famous African Americans.[96] The University of South Alabama Archives houses primary source material relating to the history of Mobile and southern Alabama, as well as the university's history. The archives are located on the ground floor of the USA Spring Hill Campus and are open to the general public.[97]

The Mobile Municipal Archives contains the extant records of the City of Mobile, dating from the city's creation as a municipality by the Mississippi Territory in 1814. The majority of the original records of Mobile's colonial history, spanning the years 1702 through 1813, are housed in Paris, London, Seville, and Madrid.[98] The Mobile Genealogical Society Library and Media Center is located at the Holy Family Catholic Church and School complex. It features handwritten manuscripts and published materials that are available for use in genealogical research.[99]

The Mobile Public Library system serves Mobile and consists of eight branches across Mobile County; its large local history and genealogy division is housed in a facility next to the newly restored and enlarged Ben May Main Library on Government Street.[100] The Saint Ignatius Archives, Museum and Theological Research Library contains primary sources, artifacts, documents, photographs and publications that pertain to the history of Saint Ignatius Church and School, the Catholic history of the city, and the history of the Roman Catholic Church.[101]

Arts and entertainment

The Mobile Museum of Art features permanent exhibits that span several centuries of art and culture. The museum was expanded in 2002 to approximately 95,000 square feet (8,826 m2).[102] The permanent exhibits include the African and Asian Collection Gallery, Altmayer Gallery (American art), Katharine C. Cochrane Gallery of American Fine Art, Maisel European Gallery, Riddick Glass Gallery, Smith Crafts Gallery, and the Ann B. Hearin Gallery (contemporary works).[103]

The Centre for the Living Arts is an organization that operates the historic Saenger Theatre and Space 301, a contemporary art gallery. The Saenger Theatre opened in 1927 as a movie palace. Today it is a performing arts center and serves as a small concert venue for the city. It is home to the Mobile Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Maestro Scott Speck.[104] Space 301 Gallery and Studio was initially housed adjacent to the Saenger, but moved to its own space in 2008. The 93,000 sq ft (8,640 m2) building, donated to the centre by the Press-Register after its relocation to a new modern facility, underwent a $5.2 million renovation and redesign prior to opening.[105] The Crescent Theater in downtown Mobile has been showing arthouse films since 2008.[106]

The Mobile Civic Center contains three facilities under one roof. The 400,000 sq ft (37,161 m2) building has an arena, a theater and an exposition hall. It is the primary concert venue for the city and hosts a wide variety of events. It is home to the Mobile Opera and the Mobile Ballet.[20] The 60-year-old Mobile Opera averages about 1,200 attendees per performance.[107] A wide variety of events are held at Mobile's Arthur C. Outlaw Convention Center. It contains a 100,000 sq ft (9,290 m2) exhibit hall, a 15,000 sq ft (1,394 m2) grand ballroom, and sixteen meeting rooms.[108]

The city has hosts the Greater Gulf State Fair, held each October since 1955.[109] The city also hosted BayFest, an annual three-day music festival with more than 125 live musical acts on multiple stages spread throughout downtown;[110] it now holds Ten Sixty Five festival, a free music festival.

The Mobile Theatre Guild is a nonprofit community theatre that has served the city since 1947. It is a member of the Mobile Arts Council, the Alabama Conference of Theatre and Speech, the Southeastern Theatre Conference, and the American Association of Community Theatres.[111] Mobile is also host to the Joe Jefferson Players, Alabama's oldest continually running community theatre. The group was named in honor of the famous comedic actor Joe Jefferson, who spend part of his teenage years in Mobile. The Players debuted their first production on December 17, 1947.[112] Drama Camp Productions and Sunny Side Theater is Mobile's home for children's theater and fun. The group began doing summer camps in 2002, expanded to a year-round facility in 2008 and recently moved into the Azalea City Center for the Arts, a community of drama, music, art, photography, and dance teachers. The group has produced Broadway shows including "Miracle on 34th Street", "Honk", "Fame", and "Hairspray".[citation needed]

The Mobile Arts Council is an umbrella organization for the arts in Mobile. It was founded in 1955 as a project of the Junior League of Mobile with the mission to increase cooperation among artistic and cultural organizations in the area and to provide a forum for problems in art, music, theater, and literature.

Tourism

Museums

Mobile is home to a variety of museums. Battleship Memorial Park is a military park on the shore of Mobile Bay. It features the World War II era battleship USS Alabama, the World War II era submarine USS Drum, Korean War and Vietnam War Memorials, and a variety of historical military equipment.[113] The History Museum of Mobile showcases 300 plus years of Mobile history and prehistory. It is housed in the historic Old City Hall (1857), a National Historic Landmark.[114] The Oakleigh Historic Complex features three house museums that attempt to interpret the lives of people from three strata of 19th century society in Mobile, that of the enslaved, the working class, and the upper class.[115]

The Mobile Carnival Museum, housing the city's Mardi Gras history and memorabilia, documents the variety of floats, costumes, and displays seen during the history of the festival season.[116] The Bragg-Mitchell Mansion (1855), Richards DAR House (1860), and the Condé-Charlotte House (1822) are historic, furnished antebellum house museums.[117][118][119] Fort Morgan (1819), Fort Gaines (1821), and Historic Blakeley State Park all figure predominantly in local American Civil War history.[120]

The Mobile Medical Museum is housed in the historic French colonial-style Vincent-Doan House (1827). It features artifacts and resources that chronicle the long history of medicine in Mobile.[121] The Phoenix Fire Museum is located in the restored Phoenix Volunteer Fire Company Number 6 building and features the history of fire companies in Mobile from their organization in 1838.[122] The Mobile Police Department Museum features exhibits that chronicle the history of law enforcement in Mobile.[123]

The Gulf Coast Exploreum Science Center is a non-profit science center located in downtown. It features permanent and traveling exhibits, an IMAX dome theater, a digital 3D virtual theater, and a hands-on chemistry laboratory.[124] The Dauphin Island Sea Lab is located south of the city, on Dauphin Island near the mouth of Mobile Bay. It houses the Estuarium, an aquarium which illustrates the four habitats of the Mobile Bay ecosystem: the river delta, bay, barrier islands and Gulf of Mexico.[125]

Parks and other attractions

The Mobile Botanical Gardens feature a variety of flora spread over 100 acres (40 ha). It contains the Millie McConnell Rhododendron Garden with 1,000 evergreen and native azaleas and the 30-acre (12 ha) Longleaf Pine Habitat.[126] Bellingrath Gardens and Home, located on Fowl River, is a 65-acre (26 ha) botanical garden and historic 10,500-square-foot (975 m2) mansion that dates to the 1930s.[127] The 5 Rivers Delta Resource Center is a facility that allows visitors to learn about and access the Mobile, Tensaw, Apalachee, Middle, Blakeley, and Spanish rivers.[128] It was established to serve as an easily accessible gateway to the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta.[129] It offers boat and adventure tours, a small theater, an exhibit hall, meeting facilities, walking trails, and a canoe and kayak landing.[130]

Mobile has more than 45 public parks within its limits, with some that are of special note.[131] Bienville Square is a historic park in the Lower Dauphin Street Historic District. It assumed its current form in 1850 and is named for Mobile's founder, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville.[132] It was once the principal gathering place for residents, when the city was smaller, and remains popular today. Cathedral Square is a one-block performing arts park, also in the Lower Dauphin Street Historic District, which is overlooked by the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception.[133]

The Fort of Colonial Mobile is a reconstruction of the city's original Fort Condé, built on the original fort's footprint. It serves as the official welcome center and a colonial-era living history museum.[29] Spanish Plaza is a downtown park that honors the Spanish phase of the city between 1780 and 1813. It features the Arches of Friendship, a fountain presented to Mobile by the city of Málaga, Spain.[134] Langan Park, the largest of the parks at 720 acres (291 ha), features lakes, natural spaces, and contains the Mobile Museum of Art, Azalea City Golf Course, Mobile Botanical Gardens and Playhouse in the Park.[131]

Historic architecture

Mobile has antebellum architectural examples of Greek Revival, Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Creole cottage. Later architectural styles found in the city include the various Victorian types, shotgun types, Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, Spanish Colonial Revival, Beaux-Arts and many others. The city currently has nine major historic districts: Old Dauphin Way, Oakleigh Garden, Lower Dauphin Street, Leinkauf, De Tonti Square, Church Street East, Ashland Place, Campground, and Midtown.[120]

Mobile has a number of historic structures in the city, including numerous churches and private homes. Mobile's historic churches include Christ Church Cathedral, the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, Emanuel AME Church, Government Street Presbyterian Church, St. Louis Street Missionary Baptist Church, State Street AME Zion Church, Stone Street Baptist Church, Trinity Episcopal Church, St. Francis Street Methodist Church, Saint Joseph's Roman Catholic Church, Saint Francis Xavier Catholic Church, Saint Matthew's Catholic Church, Saint Paul's Episcopal Chapel, and Saint Vincent de Paul. The Sodality Chapel and St. Joseph's Chapel at Spring Hill College are two historic churches on that campus. Two historic Roman Catholic convents survive, the Convent and Academy of the Visitation and the Convent of Mercy.[120]

Barton Academy is a historic Greek Revival school building and local landmark on Government Street. The Bishop Portier House and the Carlen House are two of the many surviving examples of Creole cottages in the city. The Mobile City Hospital and the United States Marine Hospital are both restored Greek Revival hospital buildings that predate the Civil War. The Washington Firehouse No. 5 is a Greek Revival fire station, built in 1851. The Hunter House is an example of the Italianate style and was built by a successful 19th-century African American businesswoman. The Shepard House is a good example of the Queen Anne style. The Scottish Rite Temple is the only surviving example of Egyptian Revival architecture in the city. The Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Passenger Terminal is an example of the Mission Revival style.[120]

The city has several historic cemeteries that were established shortly after the colonial era. They replaced the colonial Campo Santo, of which no trace remains. The Church Street Graveyard contains above-ground tombs and monuments spread over 4 acres (2 ha) and was founded in 1819, during the height of yellow fever epidemics.[135] The nearby 120-acre (49 ha) Magnolia Cemetery was established in 1836 and served as Mobile's primary burial site during the 19th and early 20th centuries, with approximately 80,000 burials.[136] It features tombs and many intricately carved monuments and statues.[137][138]

The Catholic Cemetery was established in 1848 by the Archdiocese of Mobile and covers more than 150 acres (61 ha). It contains plots for the Brothers of the Sacred Heart, Little Sisters of the Poor, Sisters of Charity, and Sisters of Mercy, in addition to many other historically significant burials.[139] Mobile's Jewish community dates back to the 1820s and the city has two historic Jewish cemeteries, Sha'arai Shomayim Cemetery and Ahavas Chesed Cemetery. Sha'arai Shomayim is the older of the two.[140]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1785 | 746 | — |

| 1788 | 1,468 | +96.8% |

| 1820 | 1,500 | +2.2% |

| 1830 | 3,194 | +112.9% |

| 1840 | 12,672 | +296.7% |

| 1850 | 20,515 | +61.9% |

| 1860 | 29,258 | +42.6% |

| 1870 | 32,034 | +9.5% |

| 1880 | 29,132 | −9.1% |

| 1890 | 31,076 | +6.7% |

| 1900 | 38,469 | +23.8% |

| 1910 | 51,521 | +33.9% |

| 1920 | 60,777 | +18.0% |

| 1930 | 68,202 | +12.2% |

| 1940 | 78,720 | +15.4% |

| 1950 | 129,009 | +63.9% |

| 1960 | 202,779 | +57.2% |

| 1970 | 190,026 | −6.3% |

| 1980 | 200,452 | +5.5% |

| 1990 | 196,278 | −2.1% |

| 2000 | 198,915 | +1.3% |

| 2010 | 195,111 | −1.9% |

| 2020 | 187,041 | −4.1% |

| 2022 (est.) | 183,289 | −2.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[141][142][143] 2020 Census[8] 2022 Estimate[9] | ||

| Historic Racial composition | 2010 | 1990 | 1970 | 1940 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 45.0% | 59.6% | 64.3% | 63.0% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 43.9% | 58.9% | 63.5%[144] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 50.6% | 38.9% | 35.4% | 36.9% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 2.4% | 1.0% | 0.9%[144] | n/a |

| Asian | 1.8% | 1.0% | 0.1% | – |

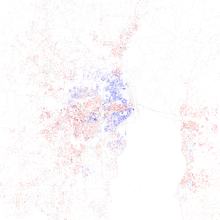

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[145] | Pop 2010[146] | Pop 2020[147] | % 2000 | % 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 98,965 | 85,613 | 75,043 | 49.75% | 43.88% | 40.12% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 91,660 | 98,202 | 95,505 | 46.08% | 50.33% | 51.06% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 463 | 572 | 513 | 0.23% | 0.29% | 0.27% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 3,011 | 3,409 | 3,369 | 1.51% | 1.75% | 1.80% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 41 | 57 | 106 | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.06% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 193 | 219 | 622 | 0.10% | 0.11% | 0.33% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 1,754 | 2,439 | 5,849 | 0.88% | 1.25% | 3.13% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 2,828 | 4,600 | 6,034 | 1.42% | 2.36% | 3.23% |

| Total | 198,915 | 195,111 | 187,041 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 187,041 people, 77,772 households, and 45,953 families residing in the city.[148] The population density was 1,341.0 inhabitants per square mile (517.8/km2). There were 89,215 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 40.12% White, 51.06% Black or African American, 0.27% Native American, 1.80% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, and 3.13% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 3.23% of the population.

2010 census

As of the 2010 census, there were 195,111 people, 78,959 households, and 48,689 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,402.6 inhabitants per square mile (541.5/km2). There were 89,127 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 43.88% White, 50.33% Black or African American, 0.29% Native American, 1.75% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, and 1.25% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 2.36% of the population.

Out of which 21,073 had children under the age of 18 living with them, 28,073 were married couples living together, 17,037 had a female householder with no husband present, 3,579 had a male householder with no wife present, and 30,270 were non-families. 25,439 of all households were made up of individuals, and 8,477 had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.

The age distribution of the population in 2010 consisted of 6.7% under the age of five years, 75.9% over 18, and 13.7% over 65. The median age was 35.7 years. The male population was 47.0% and the female population was 53.0%. The median income for a household in the city was $37,056 for 2006 to 2010. The per capita income for the city was $22,401.

Government

Since 1985 the government of Mobile has consisted of a mayor and a seven-member city council.[149] The mayor is elected at-large, and the council members are elected from each of the seven city council single-member districts (SMDs). A supermajority of five votes is required to conduct council business.

This form of city government was chosen by the voters after the previous form of government, which had three city commissioners, each elected at-large, was ruled in 1975 to substantially dilute the minority vote and violate the Voting Rights Act in Bolden v. City of Mobile. The three at-large commissioners each required a majority vote to win. Due to appeals, the case took time to reach settlement and establishment of a new electoral system.[150] Municipal elections are held every four years and are nonpartisan.[151]

The first mayor elected under the new system of single-member district (SMD) voting was Arthur R. Outlaw, who served his second term as mayor from 1985 to 1989. His first term had been under the old system, from 1967 to 1968. Mike Dow defeated Outlaw in the 1989 election; he was re-elected, serving as mayor for four terms, from 1989 to 2005. His "The String of Pearls" initiative, a series of projects designed to stimulate redevelopment of the city's core, is credited with reviving much of downtown Mobile. Upon his retirement, Dow endorsed Sam Jones as his successor.

Sam Jones was elected in 2005 as the first African-American mayor of Mobile. He was re-elected for a second term in 2009 without opposition.[152] His administration continued the focus on downtown redevelopment and bringing industries to the city. He ran for a third term in 2013 but was defeated by Sandy Stimpson. Stimpson took office on November 4, 2013, and was re-elected on August 22, 2017.[153]

As of January 2022, the seven-member city council is made up of Cory Penn from District 1, William Carroll from District 2, C.J. Small from District 3, Ben Reynolds from District 4, Joel Daves from District 5, Scott Jones from District 6, and Gina Gregory from District 7.[154]

Education

Public schools

Public schools in Mobile are operated by the Mobile County Public School System. The Mobile County Public School System has an enrollment of approximately 55,200 students at 88 schools, employs approximately 7,026 public school employees,[155] and had a budget in 2020-2021 of $623 million.[156] The State of Alabama operates the Alabama School of Mathematics and Science on Dauphin Street in Mobile, which boards advanced Alabama high school students. It was founded in 1989 to identify, challenge, and educate future leaders.[157]

Private and parochial schools

UMS-Wright Preparatory School is an independent co-educational preparatory school.[158] It assumed its current configuration in 1988, when the University Military School (founded 1893) and the Julius T. Wright School for Girls (1923) merged to form UMS-Wright.[159]

Many parochial schools belong to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mobile. These include McGill-Toolen Catholic High School (1896), Corpus Christi School, Little Flower Catholic School (1934), Most Pure Heart of Mary Catholic School (1900), Saint Dominic School (1961), Saint Ignatius School (1952), Saint Mary Catholic School (1867), Saint Pius X Catholic School (1957), and Saint Vincent DePaul Catholic School (1976).[158]

Notable Protestant schools include St. Paul's Episcopal School (1947), Mobile Christian School (1961), St. Lukes Episcopal School (1961), Cottage Hill Baptist School System (1961), Faith Academy (1967), and Trinity Lutheran School (1955).[158]

Tertiary

Major colleges and universities in Mobile that are accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools include the University of South Alabama, Spring Hill College, the University of Mobile, Faulkner University, and Bishop State Community College.

Undergraduate and postgraduate

The University of South Alabama is a public, doctoral-level university established in 1963. The university is composed of the College of Arts and Sciences, the Mitchell College of Business, the College of Education, the College of Engineering, the College of Medicine, the Doctor of Pharmacy Program, the College of Nursing, the School of Computing, and the School of Continuing Education and Special Programs.[160]

Faulkner University is a four-year private Church of Christ-affiliated university based in Montgomery, Alabama. The Mobile campus was established in 1975 and offers bachelor's degrees in Business Administration, Management of Human Resources, and Criminal Justice.[161] It also offers associate degrees in Business Administration, Business Information Systems, Computer & Information Science, Criminal Justice, Informatics, Legal Studies, Arts, and Science.[162]

Spring Hill College, chartered in 1830, was the first Catholic college in the southeastern United States and is the third oldest Jesuit college in the country.[163] This four-year private college offers graduate programs in Business Administration, Education, Liberal Arts, Nursing (MSN), and Theological Studies.[164] Undergraduate divisions and programs include the Division of Business, the Communications/Arts Division, International Studies, Inter-divisional Studies, the Language and Literature Division, Bachelor of Science in Nursing, Philosophy and Theology, Political Science, the Sciences Division, the Social Sciences Division, and the Teacher Education Division.[165]

The University of Mobile is a four-year private Baptist-affiliated university in the neighboring city of Prichard that was founded in 1961. It consists of the College of Arts and Sciences, Grace Pilot School of Business, School of Christian Studies, School of Education, School of Leadership Development, and the School of Nursing.[166]

Community college

Bishop State Community College, founded in 1927, is a public, historically African American, community college. Bishop State has four campuses in Mobile and offers a wide array of associate degrees.[167]

Vocational

Several post-secondary vocational institutions have a campus in Mobile. These include the Alabama Institute of Real Estate, American Academy of Hypnosis, Bealle School of Real Estate, Charles Academy of Beauty Culture, Fortis College, Virginia College, ITT Technical Institute, Remington College and White and Sons Barber College.[168]

Notable people

- Jerry Carl – U.S. representative[169]

- Tim Cook (born 1960) – CEO of Apple Inc.

- Rick Crawford (born 1958) – racing driver and convicted sex offender

- Anne Haney Cross (born 1956) – neurologist, section head of neuroimmunology at Washington University School of Medicine[170]

- George Washington Dennis (c. 1825 – 1916) – former slave, turned entrepreneur and real estate developer in San Francisco, California; advocate for Black rights[171][172][173]

- Michael Figures (1947–1996) – American lawyer and politician who served in the Alabama Senate

- Thomas Figures (1944–2015) – first African American assistant district attorney and assistant United States Attorney

- Flo Milli (born 2000) – rapper

- Sidney W. Fox (1912–1998) – biochemist known for studies of the origins of life

- Cale Gale (born 1985) – racing driver

- Charles F. Hackmeyer (1903–1989) – Mayor of Mobile

- Dorothy E. Hayes (1935–2015) – graphic designer, educator[174][175]

- Vivian Malone Jones (1942–2005) – director in the EPA, integrated the University of Alabama and was its first black graduate

- Charles Keller (1868–1949) – former U.S. Army Brigadier General and the oldest Army officer to serve on active duty during World War II[176][177]

- Anne Bozeman Lyon (1860–1936) – writer

- Alexander Lyons (1867–1939) – rabbi

- Thomas Praytor (born 1990) – racing driver

- Gene Tapia (1925–2005) – racing driver

- Bubba Wallace (born 1993) – racing driver

- Woodie Wilson (1925–1994) – racing driver

Healthcare

Mobile serves the central Gulf Coast as a regional center for medicine, with over 850 physicians and 175 dentists. There are four major medical centers within the city limits.

Mobile Infirmary Medical Center has 704 beds and is the largest nonprofit hospital in the state. It was founded in 1910. Providence Hospital has 349 beds. It was founded in 1854 by the Daughters of Charity from Emmitsburg, Maryland. The University of South Alabama Medical Center has 346 beds. Its roots go back to 1830 with the old city-owned Mobile City Hospital and associated medical school. A teaching hospital, it is designated as Mobile's only level I trauma center by the Alabama Department of Public Health.[178][179][180] It is also a regional burn center. Springhill Medical Center, with 252 beds, was founded in 1975. It is Mobile's only for-profit facility.[181]

Additionally, the University of South Alabama operates the University of South Alabama Children's and Women's Hospital with 219 beds, dedicated exclusively to the care of women and minors.[181] In 2008, the University of South Alabama opened the USA Mitchell Cancer Center Institute. The center is home to the first academic cancer research center in the central Gulf Coast region.[182]

Mobile Infirmary Medical Center operated Infirmary West, formerly Knollwood Hospital, with 100 acute-care beds, but closed the facility at the end of October 2012 due to declining revenues.[183]

BayPointe Hospital and Children's Residential Services, with 94-beds, is the only psychiatric hospital in the city. It houses a residential unit for children, an acute unit for children and adolescents, and an age-segregated involuntary hospital unit for adults undergoing evaluation ordered by the Mobile Probate Court.[184]

The city has a broad array of outpatient surgical centers, emergency clinics, home health care services, assisted-living facilities and skilled nursing facilities.[181][185]

Economy

Aerospace, steel, ship building, retail, services, construction, medicine, and manufacturing are Mobile's major industries. After having economic decline for several decades, Mobile's economy began to rebound in the late 1980s. Between 1993 and 2003 roughly 13,983 new jobs were created as 87 new companies were founded and 399 existing companies were expanded.[186]

Defunct companies that had been founded or based in Mobile included Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company, Delchamps, and Gayfers.[187][188][189] Current companies that were formerly based in the city include Checkers, Minolta-QMS, Morrison's, and the Waterman Steamship Corporation.[190][191]

In addition to those discussed below, AlwaysHD, Foosackly's, Integrity Media, and Volkert, Inc. are headquartered in Mobile.[192][193][194][195]

Major industry

Port of Mobile

Mobile's Alabama State Docks underwent the largest expansion in its history in the early 21st century. It expanded its container processing and storage facility and increased container storage at the docks by over 1,000% at a cost of over $300 million, a project completed in 2005.[196] Despite the expansion of its container capabilities and the addition of two massive new cranes, the port went from 9th largest to the 12th largest by tonnage in the nation from 2008 to 2010.[15][197]

Shipyards

Shipbuilding began to make a major comeback in Mobile in 1999 with the founding of Austal USA.[198] A subsidiary of the Australian company Austal, it expanded its production facility for United States defense and commercial aluminum shipbuilding on Blakeley Island in 2005.[199] Austal announced in October 2012, after winning a new defense contract and completing another 30,000-square-foot (2,800 m2) building within their complex on the island, that it would expand its workforce from 3,000 to 4,500 employees.[200]

Atlantic Marine operated a major shipyard at the former Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company site on Pinto Island. It was acquired by British defense conglomerate BAE Systems in May 2010 for $352 million. Doing business as BAE Systems Southeast Shipyards, the company continues to operate the site as a full-service shipyard, employing approximately 600 workers with plans to expand.[187][201][202]

Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley

The Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley is an industrial complex and airport located 3 miles (5 km) south of the central business district of the city. It is the largest industrial and transportation complex in the region, having more than 70 companies, many of which are aerospace, spread over 1,650 acres (668 ha).[203] Notable employers at Brookley include Airbus North America Engineering (Airbus Military North America's facilities are at the Mobile Regional Airport), VT Mobile Aerospace Engineering (a division of ST Engineering), and Continental Motors.[204]

Plans for an Airbus A320 family aircraft assembly plant in Mobile were formally announced by Airbus CEO Fabrice Brégier from the Mobile Convention Center on July 2, 2012. The plans include a $600 million factory at the Brookley Aeroplex for the assembly of the A319, A320 and A321 aircraft. It was planned to employ up roughly 1,000 full-time workers when fully operational. Construction began with a groundbreaking ceremony on April 8, 2013, with it becoming operable by 2015 and producing up to 50 aircraft per year by 2017.[205][206] The assembly plant is the company's first factory to be built within the United States.[207] It was announced on February 1, 2013, that Airbus had hired Alabama-based Hoar Construction to oversee construction of the facility.[208] The factory officially opened on September 14, 2015, covering one million square feet on 53 acres of flat grassland.[209]

On October 16, 2017, Airbus announced a partnership with Bombardier Aerospace, taking over a majority share of the Bombardier CSeries airliner program. As a result of this partnership, Airbus plans to open an assembly line for CSeries aircraft in Mobile, particularly to serve the US market. This effort may allow the companies to circumvent high import tariffs on the CSeries family.[210] The aircraft was renamed the Airbus A220 on July 10, 2018.[211] Production started in August 2019; the first A220 from the new line is due to be delivered to Delta in the third quarter of 2020.[212]

ThyssenKrupp

German technology conglomerate ThyssenKrupp broke ground on a $4.65 billion combined stainless and carbon steel processing facility in Calvert, a few miles north of Mobile, in 2007. Original projections promised eventual employment for 2,700 people. The facility became operational in July 2010.[213][214]

The company put both its carbon mill in Calvert and a steel slab-making unit in Rio de Janeiro up for sale in May 2012, citing rising production costs and a worldwide decrease in demand.[215] ThyssenKrupp's stainless steel division, Inoxum, including the stainless portion of the Calvert plant, was sold to Finnish stainless steel company Outokumpu Oyi in 2012.[216]

Top employers

According to the City's 2022 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[217] the largest employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mobile County Public School System | 7,200 | 3.85% |

| 2 | Infirmary Health Systems | 6,400 | 3.42% |

| 3 | University of South Alabama | 6,400 | 3.21% |

| 4 | Austal USA | 4,000 | 2.14% |

| 5 | City of Mobile | 2,000 | 1.07% |

| 6 | Airbus U.S. Manufacturing | 1,800 | 0.96% |

| 7 | AltaPointe | 1,700 | 0.91% |

| 8 | AM/NS Calvert | 1,600 | 0.85% |

| 9 | Springhill Medical Center | 1,600 | 0.85% |

| 10 | Mobile County | 1,600 | 0.85% |

| — | Total | 33,900 | 18.11% |

Unemployment rate

The United States Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics unemployment rate (not seasonally adjusted).[218][219]

| Mobile | Mobile County |

Mobile Metropolitan Statistical Area |

Alabama | United States | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2023 | 3.6% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 2.8% | 3.4% |

| December 2023 | 3.9% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 2.8% | 3.7% |

| January 2024 | 5.0% | 4.5% | 4.5% | 2.9% | 3.7% |

| February 2024 | — | — | — | — | 3.9% |

Transportation

Air

Local airline passengers are served by the Mobile Regional Airport, with direct connections to four major hub airports.[220] It is served by American Eagle, with service to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and Charlotte/Douglas International Airport; United Express, with service to George Bush Intercontinental Airport and Delta Connection, with service to Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport.[220] The Mobile Downtown Airport at the Brookley Aeroplex serves corporate, cargo, and private aircraft.[220]

Cycling paths

In an effort to leverage Mobile's waterways for recreational use, as opposed to simply industrial use, The Three Mile Creek Greenway Trail is being designed and implemented under the instruction of the City Council. The linear park will ultimately span seven miles, from Langan (Municipal) Park to Dr. Martin Luther King Junior Avenue, and include trailheads, sidewalks, and bike lanes. The existing greenway is centered at Tricentennial Park.[221] Other trails include the paved Mobile Airport Perimeter Trail, encircling the Mobile Downtown Airport and mountain biking trails on the west side of the University of South Alabama.

Rail

Mobile is served by four Class I railroads, including the Canadian National Railway (CNR), CSX Transportation (CSX), the Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS), and the Norfolk Southern Railway (NS).[222] The Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway (AGR), a Class III railroad, links Mobile to the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway (BNSF) at Amory, Mississippi. These converge at the Port of Mobile, which provides intermodal freight transport service to companies engaged in importing and exporting. Other railroads include the CG Railway (CGR), a rail ship service to Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, and the Terminal Railway Alabama State Docks (TASD), a switching railroad.[222]

The city was served by Amtrak's Sunset Limited passenger train service until 2005, when the service was suspended due to the effects of Hurricane Katrina.[223][224] However, efforts to restart passenger rail service between Mobile and New Orleans were revived in 2019 by the 21-member Southern Rail Commission after receiving a $33 million Federal Railroad Administration grant in June of that year.[225] Louisiana quickly dedicated its $10 million toward the project, and Mississippi initially balked before committing its $15 million sum but Governor Kay Ivey resisted committing the estimated $2.7 million state allocation from Alabama because of concerns regarding long-term financial commitments and potential competition with freight traffic from the Port of Mobile.[226]

The Winter of 2019 was marked by repeated postponement of votes by the Mobile City Council as it requested more information on how rail traffic from the port would be impacted and where the Amtrak station would be built as community support for the project became more vocal, especially among millennials.[227] A day before a deadline in the federal grant matching program being used to fund the project, the city council committed about $3 million in a 6–1 vote.[228]

About $2.2 million is still needed for infrastructure improvements and the train station must still be built before service begins. Potential locations for the station include at the foot of Government Street in downtown and in the Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley, which is favored by the Port of Mobile.[229]

Transit

The Wave Transit System provides fixed-route bus and demand-response service in Mobile.[230] Buses operate Monday through Saturday.

Roadways

Two major interstate highways and a spur converge in Mobile. Interstate 10 runs northeast to southwest across the city, while Interstate 65 starts in Mobile at Interstate 10 and runs north. Interstate 165 connects to Interstate 65 north of the city in Prichard and joins Interstate 10 in downtown Mobile.[231] Mobile is well served by many major highway systems. US Highways US 31, US 43, US 45, US 90, and US 98 radiate from Mobile traveling east, west, and north. Mobile has three routes east across the Mobile River and Mobile Bay into neighboring Baldwin County. Interstate 10 leaves downtown through the George Wallace Tunnel under the river and then over the bay across the Jubilee Parkway to Spanish Fort and Daphne. US 98 leaves downtown through the Bankhead Tunnel under the river, onto Blakeley Island, and then over the bay across the Battleship Parkway into Spanish Fort. US 90 travels over the Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge to the north of downtown onto Blakeley Island, where it becomes co-routed with US 98.[231]

Mobile's public transportation is the Wave Transit System which features buses with 18 fixed routes and neighborhood service.[232] Baylinc is a public transportation bus service provided by the Baldwin Rural Transit System in cooperation with the Wave Transit System that provides service between eastern Baldwin County and downtown Mobile. Baylinc operates Monday through Friday.[233] Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service between Mobile and many locations throughout the United States. Mobile is served by several taxi and limousine services.[234]

Water

The Port of Mobile has public deepwater terminals with direct access to 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of inland and intracoastal waterways serving the Great Lakes, the Ohio and Tennessee river valleys (via the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway), and the Gulf of Mexico.[222] The Alabama State Port Authority owns and operates the public terminals at the Port of Mobile.[222] The public terminals handle containerized, bulk, breakbulk, roll-on/roll-off, and heavy-lift cargoes.[222] The port is also home to private bulk terminal operators, as well as a number of highly specialized shipbuilding and repair companies with two of the largest floating dry docks on the Gulf Coast.[222]

The city was a home port for cruise ships from Carnival Cruise Lines.[235] The first cruise ship to call the port home was the Holiday, which left the city in November 2009 so that a larger and newer ship could take its place. The Carnival Fantasy operated from Mobile from then on until the Carnival Elation arrived in May 2010.[236] In early 2011, Carnival announced that despite fully booked cruises, the company would cease operations from Mobile in October 2011. This cessation of cruise service left the city with an annual debt service of around two million dollars related to the terminal.[237] In September 2015, Carnival announced that the Carnival Fantasy was relocating from Miami, Florida, to Mobile, Alabama, after a five-year absence and would offer four- and five-night cruises to Mexico that started in November 2016 through November 2017. The four-night cruises will visit Cozumel, Mexico while the five night cruises will additionally visit Costa Maya or Progreso.[238] Her first departure from Mobile left on November 9, 2016, on a five-night cruise to Cozumel and Progreso. Carnival Fascination will be replacing Carnival Fantasy in 2022.[239]

Although Carnival Cruise Lines did not operate from Mobile after the Carnival Fantasy left in 2011, the Carnival Triumph was towed into the port following a crippling engine room fire.[240] It was the largest cruise ship ever to dock at the cruise terminal in Mobile.[241] Later it was eclipsed by the Carnival Conquest, which docked in Mobile when the Port of New Orleans was temporarily closed.[242] Larger commercial ships routinely arrive at the Port of Mobile.

Media

Mobile's Press-Register is Alabama's oldest active newspaper, first published in 1813.[243] The paper focuses on Mobile and Baldwin counties and the city of Mobile, but also serves southwestern Alabama and southeastern Mississippi.[243] Mobile's alternative newspaper is the Lagniappe.[244] The Mobile area's local magazine is Mobile Bay Monthly.[245] The Mobile Beacon was an alternative focusing on Mobile's African-American communities that ran from 1943 to 2018.[246] Mod Mobilian is a website with a focus on cultured living in Mobile.[247]

Television