Dielli (Albanian paganism)

Dielli (Albanian indefinite form Diell), the Sun, holds a prominent position in Albanian pagan customs, beliefs, rituals, myths, and legends. The Sun exercises a great influence on Albanian major traditional festivities and calendar rites.[1] In Albanian tradition the fire – zjarri, evidently deified as Enji – worship and rituals are particularly related to the cult of the Sun.[2]

Albanians were firstly described in written sources as worshippers of the Sun and the Moon by German humanist Sebastian Franck in 1534,[3] but the Sun and the Moon have been preserved as sacred elements of Albanian tradition since antiquity. Illyrian material culture shows that the Sun was the chief cult object of the Illyrian religion.[4] The symbolization of the cult of the Sun, which is often combined with the crescent Moon, is commonly found in a variety of contexts of Albanian folk art, including traditional tattooing, grave art, jewellery and house carvings.[5] Albanian solemn oaths are often taken "by the sun", "by the ray of light", "by the sunbeam", "by the eye of the sun", or "by the star".[6]

Also referred to as i Bukuri i Qiellit ("the Beauty of the Sky"),[7] in Albanian pagan beliefs and mythology the Sun is a personified male deity, and the Moon (Hëna) is his female counterpart.[8][9] In pagan beliefs the fire hearth (vatra e zjarrit) is the symbol of fire as the offspring of the Sun.[10] In some folk tales, myths and legends the Sun and the Moon are regarded as husband and wife, also notably appearing as the parents of E Bija e Hënës dhe e Diellit ("the Daughter of the Moon and the Sun"); in others the Sun and the Moon are regarded as brother and sister, but in this case they are never considered consorts.[11][12] Nëna e Diellit ("the Mother of the Sun" or "the Sun's Mother") also appears as a personified deity in Albanian folk beliefs and tales.[13]

Albanian beliefs, myths and legends are organized around the dualistic struggle between good and evil, light and darkness, which cyclically produces the cosmic renewal.[14] The most famous representation of it is the constant battle between drangue and kulshedra, which is seen as a mythological extension of the cult of the Sun and the Moon.[15] In Albanian traditions, kulshedra is also fought by the Daughter of the Moon and the Sun, who uses her light power against pride and evil,[16] or by other heroic characters marked in their bodies by the symbols of celestial objects,[17] such as Zjermi (lit. "the Fire"), who notably is born with the Sun on his forehead.[18]

Albanian traditional festivities around the winter solstice celebrate the return of the Sun for summer and the lengthening of the days.[19][20] During the Albanian spring equinox festivity – Dita e Verës – which marks the beginning of the spring-summer period when daylight prevails over night, the Sun is celebrated, in particular by litting bonfires in yards,[21] as the god of light who fades away the darkness of the world and melts the frost, allowing the renewal of nature.[22]

Name

[edit]The Albanian word diell (definite form: dielli) is considered to have been a word taboo originally meaning "yellow, golden, bright/shiny one" used to refer to the Sun due to its perceived sacred nature. The commonly accepted historical linguistic evolution of the word is: Albanian dielli < Proto-Albanian *dðiella < *dziella- < Pre-Proto-Albanian *ȷ́élu̯a- < Proto-Indo-European *ǵʰélh₃u̯o- "yellow, golden, bright/shiny".[23]

Sunday is named e diel in Albanian, translating the Latin diēs Sōlis with the native name of the Sun.[24]

History

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

Early evidence of the celestial cult in Illyria is provided by 6th century BCE plaques from Lake Shkodra, which belonged to the Illyrian tribal area of what was referred in historical sources to as the Labeatae in later times. Each of those plaques portray simultaneously sacred representations of the sky and the sun, and symbolism of lighning and fire, as well as the tree of life and birds (eagles). In those plaques there is a mythological representation of the celestial deity: the Sun deity animated with a face and two wings, throwing lightning into a fire altar, which in some plaques is held by two men (sometimes on two boats). This mythological representation is identical to the Albanian folk belief and practice associated to the lightning deity: a traditional practice during thunderstorms was to bring outdoors a fireplace (Albanian: vatër), in order to gain the favor of the deity so the thunders would not be harmful to the human community.[25] Albanian folk beliefs regard the lightning as the "fire of the sky" (zjarri i qiellit) and consider it as the "weapon of the deity".[26]

Prehistoric Illyrian symbols used on funeral monuments of the pre-Roman period have been used also in Roman times and continued into late antiquity in the broad Illyrian territory. The same motifs were kept with identical cultural-religious symbolism on various monuments of the early medieval culture of the Albanians. They appear also on later funerary monuments, including the medieval tombstones (stećci) in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the burial monuments used until recently in northern Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro, southern Serbia and northern North Macedonia. Such motifs are particularly related to the ancient cults of the Sun and Moon, survived until recently among northern Albanians.[27]

The Illyrian Roman emperor Aurelian, whose mother was a priestess of the Sun, promoted the Sun – Sol Invictus – as the chief god of the Roman Empire.[28] Among the Illyrians of early Albania the Sun was a widespread symbol. The spread of a Sun cult and the persistence of Sun motifs into the Roman period and later are considered to have been the product of the Illyrian culture. In Christian iconography the symbol of the Sun is associated with immortality and a right to rule. The pagan cult of the Sun was almost identical to the Christian cult in the first centuries of Christianity. Varieties of the symbols of the Sun that Christian orders brought in the region found in the Albanian highlands sympathetic supporters, enriching the body of their symbols with new material.[29]

Cult, practices, beliefs, and mythology

[edit]Symbolism

[edit]

The symbolization of the cult of the Sun, which is often combined with the crescent Moon, is commonly found in a variety of contexts of Albanian folk art, including traditional tattooing, grave art, jewellery and house carvings.[31]

Solemn oaths

[edit]Albanians often swear solemn oaths (be) "by the sun" (për atë diell), "by the ray of light" (për këtë rreze drite) and "by the sunbeam" (për këtë rreze dielli).[32] The Albanian oath taken "by the eye of the sun" (për sy të diellit) or "by the star" (për atë hyll) is related to the Sky-God worship.[33]

Dualistic worldview, cosmic renewal

[edit]Albanian beliefs, myths and legends are organized around the dualistic struggle between good and evil, light and darkness, which cyclically produces the cosmic renewal.[34]

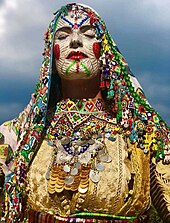

In Albanian tradition the Sun is referred to as "the Beauty of the Sky" (i Bukuri i Qiellit).[7] During the ceremonial ritual of celebration of the first day of spring (Albanian: Dita e Verës) that marks the beginning of the period of the year when daylight prevails over night, "the Beauty of the Sky" is the human who is dressed in yellow personifying the Sun, worshiped as the giver of life and the god of light, who fades away the darkness of the world and melts the frost.[22] To celebrate Dita e Verës bonfires are traditionally lit by Albanians in yards everywhere, especially on high places, with the function to drive away the darkness of the winter season allowing nature's renewal and for the strengthening of the Sun.[21][35]

The most famous Albanian mythological representation of the dualistic struggle between good and evil, light and darkness, is the constant battle between drangue and kulshedra,[36] a conflict that symbolises the cyclic return in the watery and chthonian world of death, accomplishing the cosmic renewal of rebirth.[37] The legendary battle of a heroic deity associated with thunder and weather – like drangue – who fights and slays a huge multi-headed serpent associated with water, storms, and drought – like kulshedra – is a common motif of Indo-European mythology.[38] The original legend may have symbolized the Chaoskampf, a clash between forces of order and chaos.[39] In Albanian tradition the clash between drangue and kulshedra, light and darkness, is furthermore seen as a mythological representation of the cult of the Sun and the Moon, widely observed in Albanian traditional tattooing.[15]

In Albanian mythology and folklore, the supremacy of the deity of the sky over that of the underworld is symbolized by the victory of celestial divine heroes against kulshedra (often described as an earthly/chthonic deity or demon). Those celestial divine heroes are often drangue (the most widespread culture hero among Albanians), but also E Bija e Hënës dhe e Diellit ("the Daughter of the Moon and the Sun") who is described as the lightning of the sky (pika e qiellit) which falls everywhere from heaven on the mountains and the valleys and strikes pride and evil,[16] or by other heroic characters marked in their bodies by the symbols of celestial objects,[17] such as Zjermi (lit. "the Fire"), who notably is born with the Sun on his forehead.[18]

Fire and hearth

[edit]In Albanian tradition the fire worship and rituals are particularly related to the cult of the Sun.[40] Calendar fires (Albanian: zjarret e vitit) are associated with the cosmic cycle and the rhythms of agricultural and pastoral life.[41] The practices associated with ritual fires among Albanians have been historically fought by the Christian clergy, without success.[42]

In Albanian pagan beliefs the fire hearth (vatra e zjarrit) is the symbol of fire as the offspring of the Sun.[10] The place of the ignition of fire is traditionally built in the center of the house and of circular shape representing the Sun. Traditionally the fire of the hearth is identified with the existence of the family and it is worshiped as a deity (hyjni/perëndi të zjarrit të vatrës). Its extinguishing is regarded as a bad omen for the family.[43]

The ritual collective fires (based on the house, kinship, or neighborhood) or bonfires in yards (especially on high places) lit to celebrate the main traditional Albanian festivities before sunrise are related to the cult of the Sun, and in particular they are practiced with the function to give strength to the Sun according to the old beliefs.[44]

A typical ritual practiced before sunrise during major traditional festivities such as Dita e Verës (Verëza) or Shëngjergji in the Opojë region consists in young people performing a dance on the "way of the Sun", in the east–west direction near the burning ritual fire, with which evil spirits, demons that endanger health, purification, prosperity, blessing and the beginning of the seasons are burned.[42]

Another ritual practiced during Dita e Verës in the Korçë region and called "Spring ritual" has been described as follows:[45]

"In the closed circle dance, having the fire in the center, the first ritual element is found, interlaced with choreographic motives, which classify this dance in the ritual category. The cult of fire, an important basic and ancient element, and the closed circle of the performers, a very important fact for the ritualistic choreography, create the main axis of the dance."

On the feast of Verëza, in Opojë girls go from house to house early in the morning, and two by two they go near the fire of the hearth and stir it saying to the lady of the house: Oj e zonja shpisë a e qite renin e flisë. Meanwhile, the lady of the house gives them two chicken eggs. In the morning of Verëza and Shëngjergji, the old lady of the house ties knots to the chain of the hearth and says an incantation formula, then she lights the fire, which with all its power burns the demons and evil.[46]

Ashes are believed to have healing properties, especially when children have been taken by the evil eye they are washed on the ashes.[46]

Death and burial practices

[edit]When somebody dies Albanians use to say: iu fik Dielli "the Sun went out for them".[47]

Accordin to Albanian tradition, when a person dies, they must be positioned always facing the sunrise: at home, in the yard, when resting on the way to the cemetery, as well as in the grave. This is a definite rule that finds continuity in archaeological material throughout the Middle Ages and Illyrian times.[48] Another common practice consists in making a circle of small white stones outside the grave, also associated with the cult of the Sun. This tradition too finds echoes in Illyrian times, when a ring of stones was placed around the tumulus.[48][note 1]

Mountain tops and pilgrimages

[edit]The old pagan cult of the mountain and mountain tops is widespread among Albanians. Pilgrimages to sacred mountains take place regularly during the year. This ancient practice is still preserved today, notably in Tomorr, Pashtrik, Lybeten, Gjallicë, Rumia, Koritnik, Shkëlzen, Mount Krujë, Shelbuem, Këndrevicë, Maja e Hekurave, Shëndelli and many others. In Albanian folk beliefs the mountain worship is strictly related to the cult of Nature in general, and the cult of the Sun in particular.[49] Prayers to the Sun, ritual bonfires, and animal sacrifices have been common practices performed by Albanians during the ritual pilgrimage on mountain tops.[50]

Shëndelli ("Holy Sun") is an Albanian common oronym (such as Shëndelli in Tepelenë, Shëndelli in Mallakastër, Shëndelli in the Albanian Ionian Sea Coast, etc.), which has been given to mountains in association with the cult of the mountain peaks and the cult of the Sun.[51]

The "Mountains of the Sun" (Bjeshkët e Diellit) are the places where the heroes (Kreshnikët) operate in the Kângë Kreshnikësh, the legendary cycle of Albanian epic poetry.[52]

Rainmaking and soil fertility rituals

[edit]Albanians used to invoke the Sun with rainmaking and soil fertility rituals.

In rainmaking rituals from the Albanian Ionian Sea Coast, Albanians used to pray to the Sun, in particular facing Mount Shëndelli (Mount "Holy Sun"). Children used to dress a boy with fresh branches, calling him dordolec. A typical invocation song repeated three times during the ritual was:[51]

"O Ilia, Ilia,

Peperuga rrugëzaj

Bjerë shi o Perëndi,

Se qajnë ca varfëri,

Me lot e logori

Thekëri gjer mbë çati,

Gruri gjer në Perëndi."

Afterwards, people used to say: Do kemi shi se u nxi Shëndëlliu ("We will have rain because Shëndëlliu went dark").[51]

The Sun used to be also invoked when reappearing after the rain, prayed for increased production in agriculture. A documented invocation song was:[51]

"Diell-o, Diell ti,

Aman millona, aman mullixhi,

Bluajm bereqetin, të shkoj në shtëpi,

Bluaje të butë, si për bakllava,

Bluaje të butë, si për trahana."

Another documented invocation song was:[51]

"Diell-o, Diell-o,

Hidhna një thes miell-o,

Të martojmë lalënë,

Lalë këmbëçalënë,

Që na bëri djalënë,

Në krie të vatrësë."

Animal sacrifices for building

[edit]Animal sacrifices for new buildings is a pagan practice widespread among Albanians.[53][54] At the beginning of the construction of the new house, the foundation traditionally starts with prayers, in a 'lucky day', facing the Sun, starting after sunrise, during the growing Moon, and an animal is slaughered as a sacrifice.[55]

The practice continues with variations depending on the Albanian ethnographic area. For instance in Opojë the sacrificed animal is placed on the foundation, with its head placed towards the east, where the Sun rises.[53] In Brataj the blood of the sacrificed animal is poured during the slaughter in the corner that was on the east side, where the Sun rises; in order for the house to stand and for good luck, the owner of the house throws silver or golden coins in the same corner of the house; the lady of the house throws there unwashed wool. These things are to remain buried in the foundation of the house that is being built. The relatives of the house owner throw money on the foundation of the house as well, but that money is taken by the craftsman who builds the house. In Dibra a ram is slaughered at the foundation, and the head of the ram is placed on the foundation.[55] In the Lezha highlands a ram or a rooster is slaughered on the foundation and then their heads are buried there; the owners of the house throw coins as well as seeds of different plants on the foundation.[55]

Traditional festivals

[edit]Winter solstice

[edit]Albanian traditional festivities around the winter solstice celebrate the return of the Sun for summer and the lengthening of the days.[47][19][20]

The Albanian traditional rites during the winter solstice period are pagan, and very ancient. Albanologist Johann Georg von Hahn (1811 – 1869) reported that clergy, during his time and before, have vigorously fought the pagan rites that were practiced by Albanians to celebrate this festivity, but without success.[56]

The old rites of this festivity were accompanied by collective fires based on the house, kinship or neighborhood, a practice performed in order to give strength to the Sun according to the old beliefs. The rites related to the cult of vegetation, which expressed the desire for increased production in agriculture and animal husbandry, were accompanied by animal sacrifices to the fire, lighting pine trees at night, luck divination tests with crackling in the fire or with coins in ritual bread, making and consuming ritual foods, performing various magical ritualistic actions in livestock, fields, vineyards and orchards, and so on.[56][47]

- Nata e Buzmit

Nata e Buzmit, "Yule log's night", is celebrated between December 22 and January 6.[19] Buzmi is a ritualistic piece of wood (or several pieces of wood) that is put to burn in the fire of the hearth (Albanian vatër) on the night of a winter celebration that falls after the return of the Sun for summer (after the winter solstice), sometimes on the night of Kërshëndella on December 24 (Christmas Eve), sometimes on the night of kolendra, or sometimes on New Year's Day or on any other occasion aound the same period, a tradition that is originally related to the cult of the Sun.[57][47]

A series of rituals of a magical character are performed with the buzmi, which, based on old beliefs, aims at agricultural plant growth and for the prosperity of production in the living thing (production of vegetables, trees, vineyards, etc.). This practice has been traditionally found among all Albanians, also documented among the Arbëreshë in Italy and the Arvanites in Greece until the first half of the 20th century,[57] and it is still preserved in remote Albanian ethnographic regions today.[47] It is considered a custom of Proto-Indo-European origin.[57]

The richest set of rites related to buzmi are found in northern Albania (Mirdita, Pukë, Dukagjin, Malësia e Madhe, Shkodër and Lezhë, as well as in Kosovo, Dibër and so on.[57][47]

Spring equinox

[edit]

Dita e Verës is an Albanian pagan holiday celebrated (also officially in Albania) on March 1 of the Julian calendar, the first day of the new year (which is March 14 in the Gregorian calendar). In the old Albanian calendar, Verëza corresponds to the first three days of the new year (Albanian: Kryeviti, Kryet e Motmotit, Motmoti i Ri, Nata e Mojit) and marks the end of the winter season (the second half of the year) and the beginning of the "summer" season (the first half of the year) on the spring equinox, the period of the year when daylight is longer than night. It is celebrated both in the Northern and Southern regions, but with regional differences. Bonfires are traditionally lit in yards everywhere, especially on high places, with the function to drive away the darkness of the winter season and for the strengthening of the Sun.[21][35]

Edith Durham – who collected Albanian ethnographic material from northern Albania and Montenegro – reported that Albanian traditional tattooing of girls was practiced on March 19, which falls in the days of the spring celebrations.[58]

The Mother of the Sun

[edit]Nëna e Diellit ("the Mother of the Sun" or "the Sun's Mother") is a mother goddess in Albanian folk beliefs. A sacred ritual called "the funeral of the Sun's Mother" was very widespread in southeastern Albania until the 20th century.[59] She has been described by scholars as a heaven goddess[60] and a goddess of agriculture, livestock, and earth fertility, as suggested by the sacred ritual dedicated to her.[61]

Nëna e Diellit also appears as a personified deity in Albanian folk tales.[62]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Those traditions have also been found among other European peoples. Besides being rituals for the cult of the Sun, they could have been mythic-ritualistic practices to preserve the memory of the ancestral migrations from the east, the original homeland of the Indo-European peoples in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.[48]

References

[edit]- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 68, 70, 249–254.

- ^ Qafleshi 2011, p. 49; Tirta 2004, pp. 68–69, 135, 176–181, 249–261, 274–282, 327.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (ed.). "1534. Sebastian Franck: Albania: A Mighty Province of Europe". Texts and Documents of Albanian History.

- ^ Galaty et al. 2013, p. 156; Dobruna-Salihu 2005, pp. 345–346; Tirta 2004, pp. 68–70; Egro 2003, p. 35; Stipčević 1974, p. 182.

- ^ Galaty et al. 2013, pp. 155–157; Tirta 2004, pp. 68–82; Elsie 2001, pp. 181, 244; Poghirc 1987, p. 178; Durham 1928a, p. 51; Durham 1928b, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Elsie 2001, pp. 193, 244; Cook 1964, p. 197.

- ^ a b Sokoli 2013, p. 181.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 72, 128

- ^ Dushi 2020, p. 21

- ^ a b Gjoni 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 72, 128

- ^ Dushi 2020, p. 21

- ^ Golan 1991, p. 55; Daum 1998, p. 236; Golan 2003, pp. 93–94; Tirta 2004, pp. 259–260; Neziri 2015, p. 124.

- ^ Lelaj 2015, p. 97; Doja 2005, pp. 449–462; Elsie 1994, p. i; Poghirc 1987, p. 179

- ^ a b Lelaj 2015, p. 97.

- ^ a b Shuteriqi 1959, p. 66.

- ^ a b Tirta 2004, pp. 72, 127–128.

- ^ a b Schirò 1923, pp. 411–439.

- ^ a b c Tirta 2004, pp. 249–251.

- ^ a b Poghirc 1987, p. 179.

- ^ a b c Tirta 2004, pp. 253–255.

- ^ a b Sokoli 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Crăciun 2023, pp. 77–81; Demiraj & Neri 2020: "díell -i".

- ^ Koch 2015, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Brahaj 2007, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 82, 406.

- ^ Dobruna-Salihu 2005, p. 345–346.

- ^ Belgiorno de Stefano 2014, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Galaty et al. 2013, p. 156.

- ^ Treimer 1971, p. 32.

- ^ Galaty et al. 2013, pp. 155–157; Tirta 2004, pp. 68–82; Elsie 2001, pp. 181, 244; Poghirc 1987, p. 178; Durham 1928a, p. 51; Durham 1928b, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Elsie 2001, pp. 193, 244.

- ^ Cook 1964, p. 197.

- ^ Lelaj 2015, p. 97; Doja 2005, pp. 449–462; Elsie 1994, p. i; Poghirc 1987, p. 179

- ^ a b Elsie 2001, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Lelaj 2015, p. 97; Bonnefoy 1993, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Doja 2005, pp. 449–462; Tirta 2004, pp. 121–132;Lelaj 2015, p. 97.

- ^ West (2007), pp. 358–359.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Qafleshi 2011, p. 49; Tirta 2004, pp. 68–69, 135, 176–181, 249–261, 274–282, 327.

- ^ Poghirc 1987, p. 179; Tirta 2004, pp. 68–69, 135, 176–181, 249–261, 274–282, 327.

- ^ a b Qafleshi 2011, p. 49.

- ^ Gjoni 2012, p. 91.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 75, 113, 116, 250.

- ^ Sela 2017, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Qafleshi 2011, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f Qafleshi 2011, pp. 43–71.

- ^ a b c Tirta 2004, p. 74.

- ^ Krasniqi 2014, pp. 4–5; Tirta 2004, pp. 75, 113, 116; Gjoni 2012, pp. 62, 85–86.

- ^ Tirta 2004, p. 75; Gjoni 2012, pp. 81–87.

- ^ a b c d e Gjoni 2012, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 68–70.

- ^ a b Qafleshi 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 260, 340–357.

- ^ a b c Tirta 2004, pp. 340–341.

- ^ a b Tirta 2004, p. 250.

- ^ a b c d Tirta 2004, p. 282.

- ^ Tirta 2004, p. 254.

- ^ Golan 1991, p. 55; Daum 1998, p. 236; Golan 2003, pp. 93–94; Tirta 2004, pp. 259–260; Neziri 2015, p. 124.

- ^ Golan 1991, p. 55; Golan 2003, pp. 93–94

- ^ Tirta 2004, pp. 259–260

- ^ Lambertz 1952, p. 138; Elsie 2001, p. 98; Bovan 1985, p. 241.

Bibliography

[edit]- Belgiorno de Stefano, Maria Gabriella (2014). "La coesistenza delle religioni in Albania. Le religioni in Albania prima e dopo la caduta del comunismo". Stato, Chiese e Pluralismo Confessionale (in Italian) (6). ISSN 1971-8543.

- Bonnefoy, Yves (1993). American, African, and Old European mythologies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06457-3.

- Bovan, Vlladimir (1985). "Branisllav Kërstiq, Indeks motiva narodnih pesama balkanskih Slovena SANU, Beograd 1984". Gjurmime Albanologjike: Folklor Dhe Etnologji (in Albanian). 15. Albanological Institute of Prishtina.

- Brahaj, Jaho (2007). Flamuri i Kombit Shqiptar: origjina, lashtësia. Enti Botues "Gjergj Fishta". ISBN 9789994338849.

- Crăciun, Radu (2023). "Diellina, një bimë trako-dake me emër proto-albanoid" [Diellina, a Thracian-Dacian plant with a Proto-Albanoid name]. Studime Filologjike (1–2). Centre of Albanological Studies: 77–83. doi:10.62006/sf.v1i1-2.3089. ISSN 0563-5780.

- Cook, Arthur Bernard (1964) [1914]. Zeus: Zeus, god of the bright sky. Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion. Vol. 1. Biblo and Tannen.

- Daum, Werner (1998). Albanien zwischen Kreuz und Halbmond. Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde. ISBN 9783701624614.

- Demiraj, Bardhyl; Neri, Sergio (2020). "díell -i". DPEWA - Digitales Philologisch-Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altalbanischen.

- Dobruna-Salihu, Exhlale (2005). "Cult symbols and images on funerary monuments of the Roman Period in the central section in Dardania". In M. Sanadaer, A. Rendić-Miočević (ed.). Religija i mit kao poticaj rimskoj provincijalnoj plastici. Akti VIII. međunarodnog kolokvija o problemima rimskog provincijalnog umjetničkog stvaralaštva / Religion and myth as an impetus for the Roman provincial sculpture. The Proceedings of the 8th International Colloquium on Problems of Roman Provincial Art. Golden marketing-Tehniéka knjiga. Odsjek za arheologiju Filozofskog fakulteta u Zagrebu. pp. 343–350. ISBN 953-212-242-7.

- Doja, Albert [in Albanian] (2005), "Mythology and Destiny" (PDF), Anthropos, 100 (2): 449–462, doi:10.5771/0257-9774-2005-2-449, JSTOR 40466549

- Durham, Edith (1928a). High Albania. LO Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-7035-2.

- Durham, Edith (1928b). Some tribal origins, laws and customs of the Balkans.

- Dushi, Arbnora (2020). "The Sister-Brother Recognition Motif in the Albanian Folk Ballad: Meaning and Contexts within the National Culture". Tautosakos Darbai. 59: 17–29. doi:10.51554/TD.2020.28363. S2CID 253540847.

- Egro, Dritan (2003). Islam in Albanian Lands During the First Two Centuries of the Ottoman Rule. Department of History of Bilkent University.

- Elsie, Robert (1994). Albanian Folktales and Legends. Naim Frashëri Publishing Company. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2009-07-28.

- Elsie, Robert (2001). A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology and Folk Culture. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 1-85065-570-7.

- Galaty, Michael; Lafe, Ols; Lee, Wayne; Tafilica, Zamir (2013). Light and Shadow: Isolation and Interaction in the Shala Valley of Northern Albania. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. ISBN 978-1931745710.

- Gjoni, Irena (2012). Marrëdhënie të miteve dhe kulteve të bregdetit të Jonit me areale të tjera mitike (PhD) (in Albanian). Tirana: University of Tirana, Faculty of History and Philology.

- Golan, Ariel (1991). Myth and Symbol: Symbolism in Prehistoric Religions. A. Golan. ISBN 9789652222459.

- Golan, Ariel (2003). Prehistoric Religion: Mythology, Symbolism. A. Golan. ISBN 9789659055500.

- Koch, Harold (2015). "Patterns in the diffusion of nomenclature systems: Australian subsections in comparison to European days of the week". In Dag T.T. Haug (ed.). Historical Linguistics 2013: Selected papers from the 21st International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Oslo, 5-9 August 2013. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 334. With the assistance of: Eiríkur Kristjánsson. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-6818-1.

- Krasniqi, Shensi (2014). "Pilgrimages in mountains in Kosovo". Revista Santuários, Cultura, Arte, Romarias, Peregrinações, Paisagens e Pessoas. ISSN 2183-3184.

- Lambertz, Maximilian (1922). Albanische Märchen (und andere Texte zur albanischen Volkskunde). Wien: A. Hölder.

- Lambertz, Maximilian (1952). Die geflügelte Schwester und die Dunklen der Erde: Albanische Volksmärchen. Das Gesicht der Völker (in German). Vol. 9. Im Erich.

- Lambertz, Maximilian (1949). Gjergj Fishta und das albanische Heldenepos Lahuta e Malcís, Laute des Hochlandes: eine Einführung in die albanische Sagenwelt. O. Harrassowitz.

- Lelaj, Olsi (2015). "Mbi tatuazhin në shoqërinë shqiptare" [On Tattoo in the Albanian Society]. Kultura Popullore. 34 (71–72). Centre of Albanological Studies: 91–118. ISSN 2309-5717.

- Neziri, Zeqirja (2015). Lirika gojore shqiptare (in Albanian). Skopje: Interlingua. ISBN 978-9989-173-52-3.

- Poghirc, Cicerone (1987). "Albanian Religion". In Mircea Eliade (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 1. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. pp. 178–180.

- Qafleshi, Muharrem (2011). Opoja dhe Gora ndër shekuj [Opoja and Gora During Centuries]. Albanological Institute of Pristina. ISBN 978-9951-596-51-0.

- Schirò, Giuseppe (1923). Canti tradizionali ed altri saggi delle colonie albanesi di Sicilia [Traditional Songs and other Essays from the Albanian Colonies of Sicily] (in Albanian and Italian). Stab. tip. L. Pierro.

- Sela, Jonida (2017). "Values and Traditions in Ritual Dances of All-Year Celebrations in Korça Region, Albania". International Conference “Education and Cultural Heritage”. Vol. 1. Association of Heritage and Education. pp. 62–71.

- Shuteriqi, Dhimitër S. (1959). Historia e letërsisë shqipe. Vol. 1. Universiteti Shtetëror i Tiranës, Instituti i Historisë dhe Gjuhësisë.

- Sokoli, Ramadan (2000). Gojëdhana e përrallëza të botës shqiptare. Toena. ISBN 9789992713198.

- Sokoli, Ramadan (2013) [1999]. "The Albanian World in the Folk Teller's Stories". In Margaret Read MacDonald (ed.). Traditional Storytelling Today: An International Sourcebook. Translated by Pranvera Xhelo. Routledge. ISBN 9781135917142.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1974). The Illyrians: history and culture (1977 ed.). Noyes Press. ISBN 978-0815550525.

- Tirta, Mark (2004). Petrit Bezhani (ed.). Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë (in Albanian). Tirana: Mësonjëtorja. ISBN 99927-938-9-9.

- Treimer, Karl (1971). "Zur Rückerschliessung der illyrischen Götterwelt und ihre Bedeutung für die südslawische Philologie". In Henrik Barić (ed.). Arhiv za Arbanasku starinu, jezik i etnologiju. Vol. I. R. Trofenik. pp. 27–33.

- Watkins, Calvert (1995). How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514413-0.

- West, Morris L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199280759.