Bengal School of Art

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

The Bengal School of Art, commonly referred as Bengal School,[1] was an art movement and a style of Indian painting that originated in Bengal, primarily Calcutta and Shantiniketan, and flourished throughout the Indian subcontinent, during the British Raj in the early 20th century. Also known as 'Indian style of painting' in its early days, it was associated with Indian nationalism (swadeshi) and led by Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951), and was also being promoted and supported by British arts administrators like E. B. Havell, the principal of the Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata from 1896; eventually it led to the development of the modern Indian painting.[1][2][3]

History

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History |

| Cuisine |

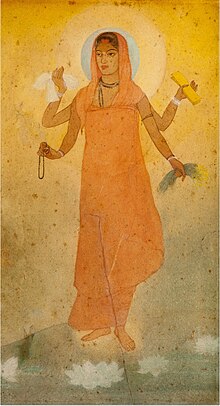

The Bengal school arose as an avant garde and nationalist movement reacting against the academic art styles previously promoted in India, both by Indian artists such as Raja Ravi Varma and in British art schools. Following the influence of Indian spiritual ideas in the West, the British art teacher Ernest Binfield Havell attempted to reform the teaching methods at the Calcutta School of Art by encouraging students to imitate Mughal miniatures.[4][5] This caused controversy, leading to a strike by students and complaints from the local press, including from nationalists who considered it to be a retrogressive move. Havell was supported by the artist Abanindranath Tagore, a nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore painted a number of works influenced by Mughal art, a style that he and Havell believed to be expressive of India's distinct spiritual qualities, as opposed to the materialism of the West. Tagore's best-known painting, Bharat Mata (Mother India), depicted a young woman, portrayed with four arms in the manner of Hindu deities, holding objects symbolic of India's national aspirations. Tagore later attempted to develop links with Japanese artists as part of an aspiration to construct a pan-Asianist model of art. Through the paintings of Bharat Mata, Abanindranath established the pattern of patriotism. Some of the notable painters and artists of Bengal school were Nandalal Bose, M.A.R Chughtai, Sunayani Devi (sister of Abanindranath Tagore), Manishi Dey, Mukul Dey, Kalipada Ghoshal, Asit Kumar Haldar, Sudhir Khastgir, Kshitindranath Majumdar, Sughra Rababi.[1]

The Bengal school's influence in India declined with the spread of modernist ideas in the 1920s. As of 2012[update], there has been a surge in interest in the Bengal school of art among scholars and connoisseurs.[6]

Bimal Sil was a contemporary of Abanindernath Tagore. He painted in water colours. His paintings are found in private collections only.

Legacy

[edit]The Bengal School of Art, which emerged in the first half of the twentieth century, has produced a significant legacy in the world of Indian art.[7] Its deep impact on the cultural landscape of India and its role in shaping the trajectory of modern Indian art cannot be overstated. Led by eminent artists such as Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, and Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengal School emerged as a powerful movement that sought to revive traditional Indian artistic practices and forge a unique national identity. However, it is important to note that "while a special kind of nationalist sentiment is present in the paintings of Abanindranath and in the ideas of Rabindranath, there was always an aversion to direct political confrontation at the core of those sentiments".[7] Artists of this style include Amit Sarkar, Ajoy Ghosh, Sankarlal Aich, Amal Chaklader, Narendra Chandra De Sarkar, Sukti Subhra Pradhan, and Ratan Acharya. Some of the best known artists of present-day Bengal are Jogen Chowdhury, Mrinal Kanti Das, Gopal Sanyal, Ganesh Pyne, Manishi Dey, Shanu Lahiri, Ganesh Haloi[8] Jahar Dasgupta, Samir Aich, Bikash Bhattacharjee, Manindra Bhushan Gupta, Sudip Roy, Ramananda Bandopadhyay and Devajyoti Ray.

R. Siva Kumar's disagreement

[edit]R. Siva Kumar, who has been studying the work of the Santiniketan masters and their approach to art since the early 80s, refutes the practice of subsuming Nandalal Bose, Abanindranath Tagore, Ram Kinker Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee under the Bengal School of Art. According to Siva Kumar, 'This happened because early writers were guided by genealogies of apprenticeship rather than their styles, worldviews, and perspectives on art practice'.[9]

His ideas on this issue are formulated in the catalogue essay of the exhibition Santiniketan: The Making of a Contextual Modernism.

See also

[edit]- Contextual Modernism

- Modern Indian painting

- Progressive Artists' Group

- Tanjore painting

- Rajput painting

- Madhubani painting

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Showcase - Bengal School". National Gallery of Modern Art.

- ^ Mitter, Partha (1994). "How the past was salvaged by Swadeshi artists". Art and nationalism in colonial India, 1850-1922: occidental orientations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 267–306. ISBN 978-0-521-44354-8. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ Onians, John (2004). Atlas of world art. London: Laurence King Publishing. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-85669-377-6. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ Mitter, Partha (2001). Indian art. Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-19-284221-8.

Ernest Binfield Havell education.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (August 19, 2008). "Art Review: Indian Modernism via an Eclectic and Elusive Artist". New York Times.

- ^ Ghose, Archana Khare (12 February 2012). "For many art lovers, it's back to the old school". The Times of India. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ a b Cohen, Jasmin (2012). "Nationalism and Painting in Colonial Bengal". Unpublished Paper – via SIT Digital Collections.

- ^ "Shanu Lahiri dead". The Telegraph (Calcutta). Archived from the original on February 7, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ "Humanities underground » All the Shared Experiences of the Lived World II".

Further reading

[edit]- Bagchi, Jasodhara. (1990). Representing Nationalism: Ideology of Motherhood in Colonial Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly, 25(42/43), WS65–WS71. JSTOR 4396894

- Eaton, Natasha. (2013). “Swadeshi” Color: Artistic Production and Indian Nationalism, ca. 1905–ca. 1947. The Art Bulletin, 95(4), 623–641. JSTOR 43188857

- Havell, E. B. (1920). A Handbook of Indian Art. John Murray, London.

- Jamal, Osman (1997). E B Havell: The art and politics of Indianness. Third Text, 11(39), 3–19. doi:10.1080/09528829708576669

- John Onians (2004). "Bengal School". Atlas of World Art. Laurence King Publishing. p. 304. ISBN 1856693775.

- Kossak, Steven (1997). Indian court painting, 16th-19th century. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870997831. (see index: p.148-152)

- Sircar, Sanjay. (1998). Shashthi’s Land: Folk Nursery Rhyme in Abanindranath Tagore’s “The Condensed-Milk Doll.” Asian Folklore Studies, 57(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178995

- Thakurta, Tapati Guha. (1991). Women as “Calendar Art” Icons: Emergence of Pictorial Stereotype in Colonial India. Economic and Political Weekly, 26(43), WS91–WS99. JSTOR 4398221

- Wong, A. Y. (2009). "6. Landscapes Of Nandalal Bose (1882–1966): Japanism, Nationalism And Populism In Modern India". In Okakura Tenshin and Pan-Asianism. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9781905246618.i-176.19