Battle of Cuarte

| Battle of Cuarte | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconquista | |||||||

Development of the Battle of Cuarte (in Spanish). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Principality of Valencia | Almoravid Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar "El Cid" | Muhammad ibn Tashfin | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

4,000–8,000 combatants Approximately half of the Muslim knights |

8,000–10,000 combatants 4,000 Almoravid light cavalry About 300 Andalusian heavy cavalry Approximately 6,000 foot soldiers.[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Low | High | ||||||

The Battle of Cuarte or Battle of Quart de Poblet was a military encounter that took place on 21 October 1094 between the forces of El Cid and the Almoravid Empire near the towns of Mislata and Quart de Poblet, located a few kilometres from Valencia.

After El Cid conquered the city of Valencia on June 17,[3][4] the Almoravid Empire assembled a large army in mid-August under the command of Muhammad ibn Tashfin, nephew of the emir Yusuf ibn Tashfin, with the aim of recovering it. Towards 15 September, Muhammad laid siege to the city, but Rodrigo came out to break the siege in a pitched battle, obtaining a decisive victory that repelled the Almoravids and secured his Valencian principality.[5]

It was possibly the most important of El Cid's victories and the first against a large Almoravid army in the Iberian Peninsula; it also halted their advance in the Levante during the remaining years of the 11th century.[6] In the 1098 diploma of endowment of the new Cathedral of Santa María consecrated on what had been the main mosque, Rodrigo signs "princeps Rodericus Campidoctor"[7] considering himself an autonomous sovereign despite not having royal ancestry, and the preamble of said document alludes to the battle of Cuarte as a victory achieved quickly and without casualties over an enormous number of Muslims.[8]

Background

[edit]On 17 June 1094, Muslim Valencia (Arabic name Balansiya) fell into the hands of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar. Yusuf ibn Tashfin, leader of the Almoravids, ordered the recruitment of some 4,000 light cavalry and between 4,000 and 6,000 infantry soldiers in Ceuta, under whose command he placed his nephew Muhammad ibn Tashfin, to undertake an expedition to try to recover the city.[9] The Almoravid army was notable for its permanent imperial guard, which was made up in part of black slaves. They were elite cavalrymen or well-equipped infantrymen who distinguished themselves by their courage and loyalty and could be organised into specialised corps, such as archers. In addition, the Almoravid army included a few hundred Andalusian heavy cavalrymen, with characteristics similar to the Christian cavalry, who may have incorporated a corps of crossbowmen, a common weapon in places that the Arabs called qaws al-ˁaqqār, qaws rūmī or ifranğī ("deadly bow", "Christian bow" or "Frankish bow"). In total, the Almoravid army numbered a maximum of 10,000 troops.[10][11]

According to the Al-Bayan al-Mughrib (History of the kings of al-Ándalus and the Maghreb) by Ibn 'Idhari, which collects the accounts of Ibn Alqama, and probably that of Ibn al-Faradi (who was wazīr, bailiff or minister of finance of the ruler Yahya al-Qadir, and of El Cid during his protectorate from 1089 to 1091), both witnesses of the events, the conflict was also triggered by the complaint of the inhabitants of the Almoravid province of Denia, who asked for help fromYusuf in the face of the continuous raids they suffered by the detachments of the Principality of Valencia.[12]

The Almoravid contingents landed on the Iberian Peninsula between 16 and 18 August 1094.[13] Passing through Granada (five days later),[13] they were joined by part of the garrison of the Almoravid governor of this province, Ali ibn Alhagg,[14] and the regular army of the former Zirid taifa integrated into the Granada military contingent,[15] and later on it is fairly certain that they were joined by Andalusian troops from the taifas of Lérida (no more than 3,000 knights under the command of their governor Sulayman Sayyid al-Dawla), Albarracín (which would not reach the hundred armed knights commanded by Abu Marwan 'Abd al-Malik, long-lived lord of the taifa between 1045 and 1103), and perhaps also from Segorbe under the orders of Ibn Yāsīn and Jérica, whose lord was Ibn Yamlūl, in which case they would contribute a few dozen mounted soldiers each, since the Andalusian Levant at this time was fragmented into fortresses governed by caids or lords who dominated little more than their alfoz; To this should be added the number of foot soldiers they provided: between 3 and 5 for each knight, counting the squires, pages and mule drivers. The presence of the personal garrisons of the Andalusian taifas that had not yet been subjected to Almoravid power had above all a political purpose, and would underline the subordination of the taifas to the Almoravid Empire. In addition, the Hispano-Arab troops were very useful due to their knowledge of Christian military techniques (they had fought alongside this cavalry on numerous occasions) and the characteristics of a siege war.[16][11]

After recruitment in Ceuta,[1] the Almoravid army crossed the Strait in several voyages, since they did not have the fleet of around a hundred ships necessary to transport the entire army simultaneously,[17] and probably landed in Algeciras.[18] From there he undertook a march of around 750 km through Málaga, Granada and Murcia, where they arrived twenty-two days after crossing the Strait, between 7 and 9 September 1094.[13][19] He then took the inland route through Villena or Alcoy, and from one of these two towns to Xàtiva, although the external route that passed along the coast and Dénia was also practicable.[18] Finally the troops camped on the plain between Quart de Poblet and Mislata, between 3 and 6 km west of Valencia,[20][19] around September 15,[13] and began the siege just before the start of the month of Ramadan, although passively during the Muslim holy month. After the fasting period ended on October 14, the Islamic army began to increase hostilities.[21]

As soon as El Campeador heard that the Almoravid army was heading towards Valencia, which happened in the first days of September, he began to take measures to resist the siege. To do this, he inspected and repaired the city walls and perhaps built new rammed earth defences to protect the suburbs and the city gates. He also proceeded to stock up on food, arm himself with weapons and gather as many warriors as possible, both Christian and Muslim, with a call to the lords and governors of the area to join his host. Although the estimate of El Cid's troops is uncertain, it is estimated that he could have gathered between 4,000 and 8,000 combatants, half of them heavy cavalry, including Christians and Andalusians.[22] El Cid's army would consist of approximately 2,000 to 4,000 knights and a similar number of foot soldiers, as well as archers and crossbowmen.[22] Furthermore, he made sure to avoid as far as possible the risk of internal rebellion or fifth columnists within Valencia itself, a very considerable danger in a city that was home to approximately 15,000 inhabitants and a large pro-Almoravid faction, which had helped to overthrow Yahya al-Qadir in 1092 and to raise Ibn Jahhaf to power immediately before Rodrigo Díaz's conquest.[23] For this reason, El Cid confiscated all the population's weapons and iron objects and expelled from the city anyone suspected of showing sympathies towards the Almoravids. Later, once the siege had begun, he also proceeded to get rid of "useless mouths" by making the women and children of the Muslims leave, whom he sent to the Almoravid camp, a usual procedure in siege situations, since they tried to keep in the city only those who were fit to fight.[24][25]

But one of the aspects most praised in El Cid by all sources, both Christian and Muslim, is his capacity for psychological warfare.[19] In this sense, Rodrigo Díaz carried out several strategies. He spread the threat that he would execute the Muslims who still remained in Valencia if the Almoravids besieged it, thereby maintaining this population in a state of submission out of fear, which could have been inclined to collaborate with the enemy; in addition, with this measure he raised the morale of the host itself.[25] To reinforce it even more, El Cid, known for his powers of ornithomancy,[26] spread the prediction that victory was going to be his. His ability to properly harangue his men should not be discounted either. However, the most effective thing was that he spread the news (whether false or true) that troops of Peter I of Aragon and Alfonso VI were going to come to the rescue;[27] Of these aids, which in the case of Alfonso VI were probably actually requested, only the king of León, also king of Castile and Toledo, responded (according to Arab sources), although the decisive battle took place when this monarch was still halfway there. Regardless of whether the request for help to these kings was historically made, the spread of the rumour that a saving army was coming not only reinforced the fighting spirit of the besieged, but also sowed unrest in the enemy army camped; which, added to the logistical difficulties inherent to such a large and heterogeneous army and the prolonged low activity during the entire month of Ramadan on campaign, generated distrust, impatience and finally dissensions among its ranks, which ended in desertions and weakened the siege. In the face of the enemy's arrival, Rodrigo also set an example with his own immutable and serene attitude when contemplating the enormous enemy camp, a fact recorded both by Ibn Alqama and by the Historia Roderici, and which in the Cantar de mio Cid (which in the parts corresponding to the Battle of Cuarte follows the Historia Roderici and another source that "would go back independently to the events themselves [...] so that its account could be put at the service of historical reconstruction, even with the caution required by its poetic nature"[28][19] It even turns into an optimistic ironic mood, when he tells his wife that the enemy camp is only wealth that will increase their assets and trousseau that they offer to their marriageable daughters, since victories were always followed by the capture of the booty.[29]

Battle

[edit]After Ramadan,[30] the Almoravids began hostilities on October 14[31] with the sound of drums, añafiles and screams, looting orchards and destroying, as far as possible, the neighborhoods outside the city walls, and accompanying their daily attacks with the firing of arrows by archers.[1]

However, the effects of psychological warfare and El Cid's propaganda that the arrival of Alfonso VI's army was imminent had already caused the defection of several Almoravid corps, leaving the southern and southwestern area of Valencia unsurrounded.[27] The demoralization and casualties of the besieging army gave El Cid the opportunity to prepare a sortie to defeat the besiegers in a pitched battle and thus break the siege.[32]

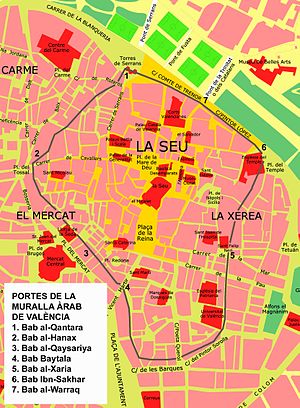

El Cid, after enduring a week of harassment by the Almoravid army, decided to attack on 21 October 1094.[30][33] He left at night or in the early hours of that day, leading the bulk of his army through the southern gates of the city (the Baytala Gate, Buyatallah or Boatella) and making a wide detour to get as far away from the Almoravid army as possible and not be discovered, to position himself behind the enemy's rearguard and camp so that, when they launched the attack from that point, it would seem to the Almoravids that Alfonso VI's reinforcements were indeed arriving from Castile.[30][32][34]

At dawn (around 6:30 a.m.),[35] another, less numerous group of Christian cavalry left the city through the western gate (Bāb al-Ḥanaš, Bab al Hanax or Snake Gate),[34] the closest to the Almoravid vanguard, simulating a quick and small attack of the kind that was usual during sieges in order to obtain some respite with skirmishes in open field that would mitigate the hardships of the siege.[30] In reality it was an attraction manoeuvre, to carry out something similar to a feigned retreat[33] and, once the bulk of the Almoravid cavalry in the vanguard had left in pursuit of this body, to begin the attack with the bulk of the Christian cavalry from the rear.[30][35][33]

This was done and the main body of the Christian army took the Almoravid camp by surprise,[30] possibly with the Almoravid general, Muhammad ibn Tashfin, in it. Believing that it was Alfonso VI who had arrived,[34] the Almoravid rearguard, already in low morale, was defeated in the clash and fled in disarray in all directions.[33] Although the rest of the Christians on the rampart had trouble defending themselves against the vanguard of the Almoravid army and suffered some casualties in their retreat, when the bulk of the Muslim troops realised that a large army was attacking from behind, they hesitated and probably became divided and disorganised. By midday, El Cid had achieved a quick victory with low casualties and driven the besieger from the camp.[36][37][34]

In this way, El Cid's army, thanks to a skilful and astute approach to the battle, achieved a decisive victory by driving the besieging army from the field and, although there was no overtaking[34] (pursuit to take advantage of the victory by obtaining the loot from the fugitives) because the flight took place in disorder and harassing the fugitives would have disorganized El Cid's troops, in addition to the fact that the greatest wealth in spoils was precisely that which the Christians looted at the expense of the Almoravid royal camp, it was a decisive victory that forced an unmitigated retreat of the besieging army.[38][34]

Consequences

[edit]The immediate consequences of Rodrigo Díaz's victory were the acquisition of an extraordinary booty in riches, horses and weapons and the recovery of hegemony in this area.[6] Indeed, in 1098 he had already conquered the important strongholds of Almenara and, above all, Murviedro (present-day Sagunto).[6] It was the first significant defeat of the Almoravids and several Taifas began to pay tribute to El Cid shortly after the battle.[39]

The victory allowed El Cid, who signed the document of endowment of the new Cathedral of Santa María in 1098 as "princeps Rodericus Campidoctor", to secure and reinforce the possession of the Principality of Valencia as a Christian stronghold until his death in mid-1099 and prevented Muslim expansion until 1102 in the Levante, which retreated to Xàtiva. All this facilitated the expansion of the Kingdom of Aragon to the south, as the Taifa of Zaragoza was isolated from Almoravid aid. Two years after the Battle of Cuarte, Peter I of Aragon conquered Huesca and allied himself with El Cid, both sovereigns collaborating in repelling a new Almoravid army in 1097 at the Battle of Bairén. It was not until 1110, long after the death of El Campeador, that the Taifa of Zaragoza fell into Almoravid hands, although they were only able to keep the capital of the middle Ebro valley under Islamic rule for eight years.[40]

After the death of El Campeador, his wife Jimena managed to defend the city with the help of her son-in-law Ramon Berenguer III of Barcelona until May 1102, when King Alfonso VI ordered its evacuation and Valencia once again passed into the hands of the Almoravids.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ferreiro 2022, p. 403.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 206.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 285-287.

- ^ Berend 2024, p. 86.

- ^ Durán 2020, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 234.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 235-238.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 127.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 133-137.

- ^ a b Aguilar 1997.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 152.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 129.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 207.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 133-147.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 153.

- ^ a b Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 149-150.

- ^ a b c d González 2020, p. 324.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 153-159.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 160.

- ^ a b Montaner Frutos & Boix Jovaní 2005, p. 167.

- ^ Ibrahim 2022, p. 83.

- ^ Corbera 2000, p. 98.

- ^ a b González 2020, p. 325.

- ^ Pénélope 2017, p. 42.

- ^ a b González 2020, p. 326.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 104-105.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 161-173.

- ^ a b c d e f Messier 2010, p. 116.

- ^ Commire 1994, p. 335.

- ^ a b Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 210.

- ^ a b c d Catlos 2014, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f González 2020, p. 327.

- ^ a b Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 211.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 211-212.

- ^ Catlos 2014, p. 121.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 175-204.

- ^ Alcaide 2022, p. 174.

- ^ Montaner Frutos 2005, p. 235.

- ^ de Molina 1857, p. 150.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aguilar, Victoria (1997). "Instituciones militares: el ejército". El retroceso territorial de Al-Ándalus: Almoravides y Almohades: siglos XI a XIII. Madrid. ISBN 978-84-239-8906-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sanz, Vicente Coscollà (2004). La Valencia musulmana. Valencia. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-84-87398-75-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Montaner Frutos, Alberto (2005). "La Batalla de Cuarte (1094). Una victoria del Cid sobre los almorávides en la historia y en la poesía". Guerra en Šarq Alʼandalus: Las batallas cidianas de Morella (1084) y Cuarte (1094). Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Islámicos y del Oriente Próximo. pp. 97–340. ISBN 978-84-95736-04-8.

- Fletcher, Richard (2007). El Cid. San Sebastián. pp. 180–184. ISBN 978-84-89569-29-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fitz, Francisco García (1998). Castilla y León frente al Islam: estrategias de expansión y tácticas militares (siglos XI-XIII). University of Seville. p. 301. ISBN 978-84-472-0421-2.

- Berend, Nora (7 November 2024). El Cid: The Life and Afterlife of a Medieval Mercenary. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-3997-0964-4.

- Commire, Anne (1994). Historic World Leaders. Gale Research Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8103-8413-2.

- Benítez, Édgar Vásquez; Pimentel, Juan Julián Jiménez; Restrepo, Darío Henao (5 June 2024). Llevarás la marca. Universidad del Valle. ISBN 978-628-7683-66-2.

- Ferreiro, Miguel Ángel (18 October 2022). La segunda columna: Lo que dejamos en África. ISBN 978-84-414-4198-9.

- Benito, Ricardo Izquierdo; Gómez, Francisco Ruiz; Mancha, Universidad de Castilla-La (1996). الارك ٨٩٢. Univ de Castilla La Mancha. ISBN 978-84-89492-34-9.

- A Companion to the Poema de mio Cid. BRILL. 10 April 2018. ISBN 978-90-04-36375-5.

- Alcaide, Luis Jiménez (14 November 2022). Historia de los reinos cristianos: Los monarcas de la reconquista, desde Don Pelayo hasta Juana la Loca. Editorial Almuzara. ISBN 978-84-1131-511-1.

- Durán, Tomás Morales Y. (26 May 2020). Teresa de Jesús: El Pútrido Olor de la Santidad. Libros de Verdad. ISBN 979-8-6525-3430-1.

- Messier, Ronald A. (19 August 2010). The Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-38590-2.

- de Molina, Manuel Malo (1857). Rodrigo el Campeador: Estudio histórico fundado en las noticias que sobre este héroe facilitan las crónicas y memorias árabes. Imprenta nacional.

- de Navascués, Faustino Menéndez Pidal (October 2015). La nobleza en España: Ideas, estructura e historia (in Spanish). Boletín Oficial del Estado. ISBN 978-84-340-2254-6.

- Corbera, Carlos Laliena (2000). Pedro I de Aragón y de Navarra, 1094-1104 (in Spanish). Editorial La Olmeda. ISBN 978-84-89915-15-2.

- Catlos, Brian A. (2014). Infidel Kings and Unholy Warriors. Macmillan + ORM. ISBN 978-0-374-71205-1.

- González, David Porrinas (25 May 2020). El Cid. Historia y mito de un señor de la guerra (in Spanish). Desperta Ferro Ediciones. ISBN 978-84-121053-7-7.

- Cartelet, Pénélope (3 January 2017). 'Fágote de tanto sabidor'. La construcción del motivo profético en la literatura medieval hispánica (Siglos XIII-XV). e-Spania Books. ISBN 978-2-919448-11-1.

- Montaner Frutos, Alberto; Boix Jovaní, Alfonso (2005). Guerra en Sarq Al'andalus: Las batallas cidianas de Morella (1084) y Cuarte (1094) (in Spanish). Instituto de Estudios Islámicos de Oriente Próximo. ISBN 978-84-95736-04-8.

- Ibrahim, Raymond (26 July 2022). Defenders of the West: The Christian Heroes Who Stood Against Islam. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-64293-821-0.